Duncan Green's Blog, page 84

October 18, 2018

Legal earthquakes and the struggle against Mining in Mexico

Curse of wealth? Gold and Silver mines in Mexico

Second post from a great visit to Mexico last week to launch the Spanish language edition of How Change Happens.

Few things get development folk fired up as much as mining. For many NGOs and grassroots organizations, not much has changed since the Conquistadores: mining is plunder. Given their long history in terms of pollution, community division, and human rights abuses, mining companies should stay away.

I’m not one of those people. What about Botswana’s ability to turn diamonds into development? Or Malaysia? But I had to put those objections aside on my recent trip to Mexico, during a brief and fascinating immersion in a world of indigenous struggle and lawyers in Oaxaca. The visit brought home to me the pivotal role of the law, and the reasons for opposing mines.

First the law. In Oaxaca, it feels like a parallel system to politics and economics. Not totally divorced of course – politicians and big money can still influence the courts – but there is also significant autonomy; the legal system in Mexico has been making progress, even when economics and (maybe) politics was going in the other direction.

One big victory came in 2013, when the Supreme Court ruled that any international human rights treaties signed by Mexico had the same legal status as the constitution. And there are a lot of them – Mexico has always seen itself as an international good guy, a refuge for those fleeing persecution since the days of the Spanish Civil War and Latin America’s military dictatorships. That meant it signed on to more international human rights treaties than almost any other government.

What’s more, Mexican politics is highly constitutionalist – ‘if it’s not in the constitution, it doesn’t exist. They need to see which article you are talking about’, said one indigenous human rights lawyer.

The result is a potential legal earthquake, and the caseload is building – you can now take the Mexican government to court for violations of any number of international treaties.

That ruling is part of a steady growth in the role of legal activism, especially with regards to Mexico’s indigenous peoples. People put the start down to the Zapatista uprising of 1994, which raised awareness of Mexico’s apartheid-like ‘indigenous problem’. Recognition of indigenous rights followed in a series of agreements, (not always implemented, such as the San Andrés Accords), with a key focus being that in the indigenous world order, collective rights are often as, or more, important than individual ones.

That ruling is part of a steady growth in the role of legal activism, especially with regards to Mexico’s indigenous peoples. People put the start down to the Zapatista uprising of 1994, which raised awareness of Mexico’s apartheid-like ‘indigenous problem’. Recognition of indigenous rights followed in a series of agreements, (not always implemented, such as the San Andrés Accords), with a key focus being that in the indigenous world order, collective rights are often as, or more, important than individual ones.

The law is well ahead of practice, but that creates all sorts of avenues for putting pressure on the state – it all reminded me of a conversation with a Spanish lawyer a few years ago, who told me ‘You must understand, the state sees the world through the eyes of the law’.

But what everyone from human rights lawyers to community leaders stress is that this only works when pressure from the law is matched by pressure from grassroots social movements.

So we headed off to look at what is happening on the ground, in the endless skirmishes between mining companies and indigenous communities. We arrive at the indigenous community of San Jose del Progreso through great white lifeless mounds of tailings from a big Canadian-owned gold and silver mine on the edge of town (Fortuna Silver Mines Inc). We talk to Don Chico, one of the leaders of a besieged band of opponents of the mine – the Coordinadora de Pueblos Unidos del Valle de Ocotlan. In the community hall where I meet Don Chico, there is a shrine to a leader shot dead in 2011 by gunmen on the road we have just driven down. The culprits are already out of jail and even worked as guards for the local mayor.

Don Chico’s tale is familiar from any number of natural resource conflicts around the world. The municipal and indigenous leaders did a deal with the company behind closed doors, so the mine and the state could then say they had the green light through consultation. When the rest of the community found out, there were protests and fights (‘there was blood’). ‘We asked to see the agreements, and they always said ‘they’ll soon be ready – they’re just being drafted’. But we’ve never seen anything’. Since then ‘it’s changed. After 3 or 4 years, everyone could see the jobs, see others driving trucks, making money – people started to leave us.’ Community cohesion has been destroyed – Don Chico is still not talking to his sister, who joined the pro-mine faction.

‘We are in the ruins’, he concludes. Now he just wants to warn other communities not to follow San Jose’s path to pollution (he says the dust from the mine is killing the crops), falling water levels and social division. ‘People think the mine will make us powerful, but that’s only true for a few people.’

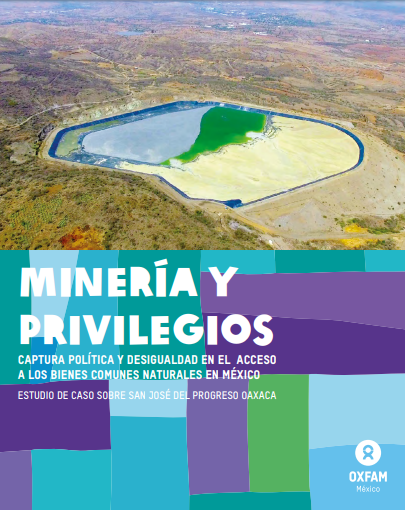

That link between mining and inequality is the subject of a new Oxfam Mexico report (in Spanish), Minería y Privilegio. One of the main points the report makes is that the current legal framework grants a “public utility” and “prominent economic activity” status to mining; this gives the mining companies privileged access to natural resources, such as free and unrestricted use of water, creating an in-your-face inequality compared to the restrictions imposed on small-scale farming communities. Oxfam Mexico’s 2015 Extreme Inequality report, highlighted how the four richest people in the country – three of whom own a mining company – made their fortunes in sectors that had either been privatized, licensed and/or regulated by the Government – such as mining – thanks to tax breaks and the lack of regulation.

Don Chico, credit: Oxfam Mexico

One of the communities Don Chico has been warning is Santa Catarina Minas, a 15m drive away. Oddly, given its name, Santa Catarina has no mine and wants to keep it that way. We meet 15 community leaders in the ‘Centro de Bienes Comunes’ (the local agrarian authorities’ office), a cool hall in the midday heat, with a big mural of the iconic image of Zapata, in big hat and Mexican sash and his battle cry ‘Tierra y Libertad’ (land and freedom). Over and over, they repeat the slogan ‘no a la mina’. ‘We have another way of life – we’re doing fine.’ That way of life seems to involve a lot of eating and drinking – we munch our way through bags of tasty fried grasshoppers, then get a guided tour of one of the many ‘palenques’ – stills fermenting the maguey cactus into tasty varieties of mezcal. Mezcal production, along with a lot of greenhouses and agro-industry, is leading to a fall in outmigration and creating viable alternatives to letting in the mines.

‘If the mine comes, 2 or 3 people get rich, everyone else loses. We’ll end up fighting – we want to live as brothers, united. What’s the point of jobs and income if it destroys our community?’ Santa Catarina is planning to join a growing number of communities declaring themselves ‘mining free’ to try and prevent the kind of foot in the door/divide and rule tactics that caused such division in San Jose Progreso.

Last week, Oxfam Mexico published two reports (in Spanish): Minería y Privilegio links Mexico’s dependence on mining with its severe levels of inequality; Implementación de la Consulta y Consentimiento Previo, Libre e Informado discusses the system of community consultation and the role of FPIC.

Special thanks to Roberto Stefani for help with this post, and with my visit.

And here I am saying some of this into my phone in Oaxaca

The post Legal earthquakes and the struggle against Mining in Mexico appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

October 17, 2018

Is Something Good about to happen in Mexico?

First of two reflections on last week’s visit to Mexico.

Omar Cabezas’ wonderful account of the Sandinista Revolution, Fire from the Mountain, ends with the victorious

Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador

guerrillas arriving in Managua’s main square, where wild celebrations break out at the overthrow of the Somoza dictatorship. On the margins of the fiesta, a group of comandantes gather and look at each other. One asks plaintively ‘now what do we do?’

Mexico’s civil society feels a bit like that at the moment. Following the overwhelming victory of Andrés Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO) and his Morena party, confusion is great, but so are expectations (though always tempered with Mexicans’ deep strain of pessimism).

The sources of confusion are several. AMLO is a complex character, both authoritarian and deeply connected to ‘el pueblo’. His party includes both progressive technocrats and populists. And his attitude to civil society organizations is at best, ambivalent.

If you want to know more, while in Mexico I interviewed Oxfam Mexico’s boss, Ricardo Fuentes, for the first ever FP2P podcast (25 minutes). First of many, I hope. Please tell me what you think:

Soon after the election in July (AMLO takes office on 1st December), his team could be heard dismissing CSOs as ‘fifi’ (posh). With a landslide election victory, AMLO was the authentic voice of the people, not these middle class do gooders.

Since then the tone has moderated somewhat, but CSOs are anxious, excited and uncertain. What should be their role in what AMLO calls Mexico’s ‘fourth transformation’? They face big existential questions: is the role of CSOs to speak truth to the new power, to act as a loyal opposition, or to act as change agents with their own agenda, which may include cooperating with the state?

Not surprisingly, the subject dominated the conversations at various events to launch ‘Como Ocurren los Cambios’  last week. We all ended up combing through the book’s arguments to see what ideas they prompted. Some of the main topics included:

last week. We all ended up combing through the book’s arguments to see what ideas they prompted. Some of the main topics included:

Dancing with the System: the confusion includes which of the many currents within Morena will dominate, who gets what position, and how the priorities announced by AMLO will be turned into specifics. At such a time, CSOs need acute political antennae. After watching Oxfam Mexico’s Ricardo Fuentes schmoozing the incoming economic team in their favourite cantina, I’m pretty confident that at least some people are on it.

The fog: but for a while, things will be uncertain. CSOs face a tough choice. If they wait until everything is clear before deciding how to engage with the new government, they may reduce the risks of backing the wrong horse, or alienating leaders early on, but will miss the chance to shape what emerges from the fog.

Seeing the government as a system, not a monolith: That intel should inform CSOs’ understanding of the system – the currents, the potential allies, the likely enemies. Weakening the bad guys, and working to strengthen the hand of the progressive voices in government, could be a real contribution to Mexico’s prospects.

Their agenda or ours? The new government already has a packed agenda, including lots of reforms to the apparatus of the state, a focus on security, infrastructure, youth and anti-corruption. There is plenty CSOs could be doing to promote social justice within that list, but other things dear to their heart (eg gender rights) are not on it. Is it better to work with Morena’s feminist leadership in Congress to change that, or stick to the existing script?

Seeing through their eyes: CSOs need to think how the current situation looks through the eyes of AMLO and the new leadership. What do they want and need in the early months? Any government wants some quick wins to build momentum and morale – could CSOs help with that and buy themselves some political space into the bargain? One option that Oxfam Mexico is clearly interested in is tax collection. Mexico has one of the lowest rates of tax collection in the OECD – could we do something to improve that, eg by a league table of which municipalities are failing as to collect the local taxes that are owing? If the new government does do some good things, will CSOs be able to celebrate them without adding the inevitable ‘but’?

Feedback: Once he enters the presidential palace, AMLO, like any leader, will be surrounded by sycophants. Officials and political hacks will be reluctant to bring him news of failures and screw-ups. Is there a way that CSOs can do so, without being branded as enemies? Mexican governments have long struggled to give a proper role to opposition and criticism, but maybe this time is different. A lot depends on the tone and relationships CSOs can bring to bear on the conversation.

Feedback: Once he enters the presidential palace, AMLO, like any leader, will be surrounded by sycophants. Officials and political hacks will be reluctant to bring him news of failures and screw-ups. Is there a way that CSOs can do so, without being branded as enemies? Mexican governments have long struggled to give a proper role to opposition and criticism, but maybe this time is different. A lot depends on the tone and relationships CSOs can bring to bear on the conversation.

Stopping bad stuff: there will be some dumb things that need to be stopped. An early candidate appears to be the ‘Maya Train’ infrastructure project in the South of the Country. How to do that without being branded as an enemy of the people?

Although some CSOs may stick to ‘denuncia as usual’, those that decide to engage will need to review their tactics and alliances. If they are being denounced as fifi, then a big CSO coalition may be less useful than pulling in some ‘unusual suspects’, such as academics, faith leaders and the like. More broadly, CSOs are reflecting on their legitimacy – have they indeed become too divorced from the grassroots movements they seek to support?

Finally, this will be a big challenge to CSOs as a movement. Moments of victory are always dangerous for campaigners – the gains are always partial, triggering disputes between reformists and hardliners. Will Mexican civil society have the maturity to create spaces where people can talk and manage the inevitable tensions?

I really hope so. This moment may not come again for Mexico. A lot is at stake.

The post Is Something Good about to happen in Mexico? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

Should aid workers and academics fly? Time to vote on the best approach, please.

Thea Hilhorst’s post has generated a lot of traffic and interest, so it’s time to push you a bit. We’ve come up with 9 statements reflecting different views of the relative importance of the issue, and the kinds of measures development workers and academics should take. You can select a maximum of 4 of these – those you most strongly agree with. If you think the real issues and dilemmas are different from those presented here, please say so in comments. Over to you:

Note: There is a poll embedded within this post, please visit the site to participate in this post's poll.

The post Should aid workers and academics fly? Time to vote on the best approach, please. appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

October 16, 2018

Is Flying the new Smoking? If so, should aid workers stop flying?

suggested this just after I had got off a plane to Mexico, so I figured I had to publish it….

Flying is an important contributor to global heating, and by far one of the most complicated. There are no signs that flying will be reduced and technical solutions to reduce carbon emissions are a long way off and not very feasible. Unlike cars, electric planes are not an option – flying a plane would require its entire space to be filled with batteries.

The IPCC report that came out last week is absolutely terrifying. The possibility of retaining global heating within 1.5 degrees is rapidly disappearing and we are facing a heating of 2 or even 3 degrees. The report contains convincing evidence of the devastation of that extra degree on biodiversity, sea level rise, disaster events, the economy, coral reefs, and so on.

With regards to flying, governments should get their acts together and start taxing air travel, while investing in alternatives, especially a huge expansion of fast train networks. But in the meantime, I think organisations and their employees should also take some level of responsibility.

The IPCC report comes out in the midst of a scandal over the irresponsible ‘flying behaviour’ of Erik Solheim, the director of the United Nations Environment Programme, who travels 80% of his time. In the coverage of the scandal, most attention centred on his flying for private purposes. This reflects a general view that private flying is a luxury, but business-related travel is just what needs to be done. But is that really true? I’m pretty sure that huge cuts could easily be made in business-related air travel.

The IPCC report comes out in the midst of a scandal over the irresponsible ‘flying behaviour’ of Erik Solheim, the director of the United Nations Environment Programme, who travels 80% of his time. In the coverage of the scandal, most attention centred on his flying for private purposes. This reflects a general view that private flying is a luxury, but business-related travel is just what needs to be done. But is that really true? I’m pretty sure that huge cuts could easily be made in business-related air travel.

There is now a call for environmental guidelines within the UN. What, only now??? Shocking, right? But let’s be honest, the whole aid and development world – UN, NGOs, and my own world of the academic departments and development studies – is shamefully late in taking responsibility. For decades, I have not given my flying behaviour much thought either, and found it normal or at best a necessary evil to hop on a plane for every piece of research, conference or seminar.

I will not go into name-shaming, but I know for a fact that some of the front runner developmental institutes and think tanks are not using carbon offsetting for their flights, and have no policy on reducing air travel. Since a few years back, I have tried to reduce my own air travel. I still have an oversized ecological footprint, but I fly significantly less than I used to.

I also – cautiously – try to bring up the topic in conversations with people I work with. Here some experiences:

1) when preparing a lecture at a development institute in the UK: “Sorry, we are short on budget this year, would you

mind taking the plane rather than the train?”

2) A director of a development department in the Netherlands: “Sorry, we are too busy we will consider introducing a policy next year”.

3) A consultant coming over for an assignment: “Really, is there now a train connecting London to Amsterdam in less than four hours? I didn’t know”.

Two further defences are that people start laughing when I raise this issue, because they consider air-travel to be at the core of who we are; or that they point at real polluters, usually big business or an American president. Good points, but my reading of the IPCC report is that all of us need to step up the effort: governments, business, institutions, employees and consumers.

I also know many people that refuse to carbon offset because some offset programmes are open to criticism, or

This OK, Thea?

because they find this tokenistic. However, offsetting is a first step. While the IPCC focuses on the devastation of future temperature rises, it is absolutely clear that climate change is already wreaking havoc, especially for poor people in poor countries.

More droughts, floods, fires. More hunger, poverty, and distress migration. It is a core principle in environmental politics that polluters should pay. There are a number of offset schemes that take this into account and use the money they generate for programs that combine livelihoods with mitigation of carbon emission, for example by protecting the vast peat areas in the world that contain huge levels of carbon. If only for this reason, a simple measure such as offsetting every flight you take should not be too much to ask.

But compensation programmes can only ever be a first small step. Next comes sharply reducing the number of flights we take.

Of course, there are already signs of these changes, and best practices are rapidly evolving. I have the feeling that NGOs may be ahead of the game compared to universities and research institutes. We academics may even be worse than the United Nations or some companies. Some obvious things we could do:

Some NGOs (like Oxfam – see below) have ruled that travel below xx hours cannot use air travel. I have not yet heard of a single University that sets such rules.

No more face-to-face job interviews, where applicants are invited to fly in so that the personal chemistry can be tested.

Organise international conferences of study associations every three or four years rather than every year.

Get used to teaching and seminars through Skype

Introduce a rule that planes must be booked well in advance to avoid that the only available or affordable ticket comes with three stops and huge detours.

Invest more in identifying and fostering local experts to avoid international consultancies.

How far can we get in 8 hours?

I’m sure there are plenty more examples, and would love to hear suggestions. Taxing carbon use and investing in green transport systems like fast trains will definitely help to reduce air travel. What we really need, though, is a change of mentality. Let’s stop kidding ourselves. Let’s get ready for an era where flying is the new smoking. It won’t be long before people who fly have some awkward explaining to do over the Friday afternoon drinks after work.

And in case you’re interested, I dug out the Oxfam travel policy, which says the following: ‘ For travel within the UK or to parts of Europe directly served by Eurostar, rail travel must become the norm. No flights are permitted for travel where the destination is reachable within eight hours door to door.’

This post was simultaneously published on the blog of ISS on global development and social justice.

The post Is Flying the new Smoking? If so, should aid workers stop flying? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

October 15, 2018

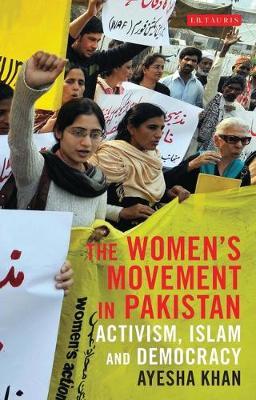

How Aid has helped Pakistan’s Women’s Movement achieve Political Breakthroughs

Do aid dollars help or hinder the women’s movement? In Pakistan, there are advocates of both points of view. I believe that my recent research as part of the Action for Empowerment and Accountability (A4EA) programme has gathered enough evidence to settle it: there is a strong case in favor of long-term external support for increasing women’s political participation.

In today’s environment of shrinking civil spaces and post 9/11 suspicion of the West, it can seem that the opposite is true. I met with a group of women in Mardan, an area in Khyber Pakhtoonkhwa province where the effects of Taliban militancy and the war on terror make it difficult for community-based organizations to work openly. They told me that religious leaders, in their sermons at local mosques, refer to NGOs as ‘No God Organizations’. The implicit links between foreign funding, NGO work, and atheism puts local staff at risk of being accused of blasphemy, which is punishable by death in Pakistan.

The women I met in Mardan were part of the UK Aid-funded Awaaz programme, working at the community level to encourage women to engage in the political process. This included helping them get identity cards, which is a requirement for voter registration. (There is a 12 million person gender gap in registered voters, which could not be closed in time for the 2018 elections.)

Even though they were working in conflict-affected and deeply conservative communities, the Awaaz work gave some of the women I interviewed the confidence to enter electoral politics. One woman ran for a general seat on the union council, (the first tier of local government), and won. Another is now the secretary of the women’s wing of a newly established left-wing political party. Even religious parties, who position themselves as anti-western/imperialist, and conflate aid organizations with the same forces who conduct unpopular drone attacks in the region against militants, have benefited from the activist-NGO-donor nexus in the area of women’s political participation by gradually allowing women to serve as elected representatives.

The turning point was the restoration of quotas of reserved seats for women in all elected bodies, a process begun in 2001 (they had lapsed in 1988). My new book on the women’s movement in Pakistan shows how activists’ demand for a women’s quota in elected assemblies has transformed political discourse and legislation once reserved seats were restored. My current A4EA research on women’s political participation examines how the women’s movement ran its campaign for this quota throughout the 1990s, which created a political consensus in support of General Musharraf’s decision to grant increased quotas. Aurat Foundation, an NGO led by women activists, conducted intensive lobbying with politicians from across the spectrum. It developed grass-roots citizen’s actions groups in districts all over the country to create constituency-level demand for the quota that built up pressure on these same politicians from below.

The turning point was the restoration of quotas of reserved seats for women in all elected bodies, a process begun in 2001 (they had lapsed in 1988). My new book on the women’s movement in Pakistan shows how activists’ demand for a women’s quota in elected assemblies has transformed political discourse and legislation once reserved seats were restored. My current A4EA research on women’s political participation examines how the women’s movement ran its campaign for this quota throughout the 1990s, which created a political consensus in support of General Musharraf’s decision to grant increased quotas. Aurat Foundation, an NGO led by women activists, conducted intensive lobbying with politicians from across the spectrum. It developed grass-roots citizen’s actions groups in districts all over the country to create constituency-level demand for the quota that built up pressure on these same politicians from below.

None of this work would have been possible without consistent and growing support from international aid agencies – in this case the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) played the most important role. Other donors, including UK Aid, UNDP, Unicef and UNIFEM, often locally staffed by Pakistan women’s rights activists, joined in to support the campaign. Activists who took part recalled how aid agencies took decisions during the 1990s within a broader global context that gained momentum from a strong international feminist movement and landmark UN conferences – Vienna ’93, Cairo ’94 and Beijing ’95 – after which Pakistan committed to act on women’s rights and signed CEDAW. The many Pakistani women activists who served in local offices of these donor agencies pushed both their own government and these agencies to stay focused on gender outcomes.

The most satisfying part of the story took place when women came into politics via reserved seats. Almost 40,000 women entered local government on the 33 per cent quota during the 2001-2 elections, upending expectations that there would not be enough women to fill the reserved seats. In fact, large numbers of them had their initial training through Aurat Foundation’s campaign work. (In what activists call a patriarchal backlash, Musharraf soon halved the number of local council seats.)

Today the four provincial assemblies, National Assembly and Senate have a 17 per cent reservation for women. During the last two civilian governments (2008-13 and 2013-18) these women pushed for a wave of progressive legislation, to curb domestic violence, honour killings, sexual harassment, acid burnings, customary practices detrimental to women, and raise the legal age at marriage for girls from 16 to 18.

When I mapped out progressive legislation for women by government types and levels of women’s political  representation, beginning with Pakistan’s formation in 1947, I found that it was only in this latter period that new laws began to substantively address what Htun and Weldon (2010) call ‘doctrinal’ issues. These are reforms in religious laws or cultural practices – areas where Pakistan’s religious political parties strongly resist any relaxation in ultra-conservative interpretations of doctrine or practice.

representation, beginning with Pakistan’s formation in 1947, I found that it was only in this latter period that new laws began to substantively address what Htun and Weldon (2010) call ‘doctrinal’ issues. These are reforms in religious laws or cultural practices – areas where Pakistan’s religious political parties strongly resist any relaxation in ultra-conservative interpretations of doctrine or practice.

Again, this wave of legislation owes much to activism from the women’s movement and advocacy NGOs such as Aurat Foundation, as well as technical support/training of women legislators provided by the donor community. Some feminists fear that Pakistan is turning into an over-legislated country, in which we pay scant attention to effectively implementing our spate of new laws. But there can be no denying that political parties, at least the mainstream ones, have begun to take women’s issues seriously enough to give progressive laws their vote.

Yet hurdles remain, some of them quite petty. Cross-party caucuses for women struggled even to find a room for their meetings. Since the Women’s Parliamentary Caucus was formed in 2008, it has been forced to rely on donor support for training, research, hiring staff, and developing their legislative agenda. Women elected (indirectly by their party legislators) on reserved seats are referred to by male colleagues as ‘khairati’ (charity) seat-holders, and media critics deride them as ‘male proxies’ – stand-ins for relatives who could not run themselves.

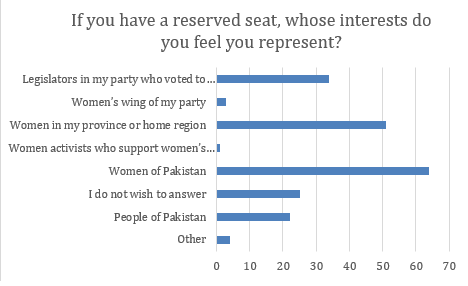

In an online survey my team conducted, women elected representatives report being denied opportunities to speak and coming under pressure to tow the party line. Yet when asked whose interests they believe they represent, 75 per cent cited women in their home region, women of Pakistan, or the people of Pakistan – and only 19 per cent felt accountable to the party colleagues who elected them. So far, the outcomes of their work as legislators bear this out.

The post How Aid has helped Pakistan’s Women’s Movement achieve Political Breakthroughs appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

October 14, 2018

What can Positive Deviance reveal about gender and social change?

Today is the UN International Day for Rural Women, so here are Patti Petesch (left), Shelley Feldman (near right) and Lone Badstue (far right) to introduce some really interesting new research on what

works.

works.

What can a Positive Deviance approach add to our of gender equality in rural villages? To find out we analysed a sample of 79 villages in 17 countries and identified eight that we classify as ‘transforming’. Diverse villagers from these eight cases reported significant gains in their decision-making capacity and in local poverty reduction compared to a decade ago. The remaining 71 villages fall into two groups: ‘climbing’ (villages with more modest improvements) and ‘churning’ (stagnating or deteriorating places). Here’s our paper with further details.

Headline finding: Transforming communities are distinguished by more equitable gender norms that enable both women and men to be more effective decision-makers and innovators in their rural livelihoods. Compared to climbing and churning cases, both women and men in the transforming villages attest to greater freedoms for women to be mobile in their villages and to innovate with commercial crops, agri-processing and other entrepreneurial activities.

In a transforming village of Nigeria’s Oyo state, for instance, women along with men report benefiting greatly from improved maize and cassava varieties. Village women process their cassava into speciality drinks and prepare foods that they vend in the busy village market. “Everybody is into business now,” says one woman. Women with more resources in the Oyo village report having control over farmland and now make enough money “to allow us to enjoy the freedom to make major decisions.”

In a transforming village of Nigeria’s Oyo state, for instance, women along with men report benefiting greatly from improved maize and cassava varieties. Village women process their cassava into speciality drinks and prepare foods that they vend in the busy village market. “Everybody is into business now,” says one woman. Women with more resources in the Oyo village report having control over farmland and now make enough money “to allow us to enjoy the freedom to make major decisions.”

Aside from women and men connecting to opportunities, the transforming communities are also characterized by infrastructure investments, growing markets and men’s labour migration.

For example, in another transforming context in Uzbekistan’s Andijan Province, about half the village men work in temporary jobs in Russia and Kazakhstan. In men’s absence, many village women have stepped into commercial farming. They spoke of receiving valuable support from business-friendly government programs, the farming association and commercial bank loans. “We [women] need to work and take matters into our own hands and head our households,” said the local social worker.

The need for a confluence of so many favourable conditions helps to explain why we found so few transforming cases

but you knew that, right?

in our sample (8 out of 79). It takes not only a flowering of more equitable normative practices, but also an environment providing opportunities for women and men alike to exercise agency, to access meaningful resources, and to forge good change in their own and their family’s wellbeing.

In another transforming context, a village in Uttar Pradesh, India, also with very high rates of men’s outmigration and women assuming operation and management of family farms, the women often consult with their absent husbands via cellphone. The women also speak of becoming more assertive in their households. Young women of the village report freedom to move about and engage in small-scale trade and testify to social change in their own young lives: “Education has brought about a revolutionary change—we are wiser and more capable.”

We found women actively engaged in their rural economies across the climbing and churning contexts too, but with far less encouragement, visibility and returns. “Tough men like my husband don’t give me freedom to make decisions,” explains a 50-year-old farmer and mother of six from a climbing context, also in Nigeria’s Oyo State. There are countless pressures on women to keep their economic lives small and out of sight. In many contexts, still, men’s reputations depend on this. Moreover, our wider data make evident that extension systems continue to provide limited support to boosting women’s productivity, despite so many women farming and men off in distant jobs.

We found women actively engaged in their rural economies across the climbing and churning contexts too, but with far less encouragement, visibility and returns. “Tough men like my husband don’t give me freedom to make decisions,” explains a 50-year-old farmer and mother of six from a climbing context, also in Nigeria’s Oyo State. There are countless pressures on women to keep their economic lives small and out of sight. In many contexts, still, men’s reputations depend on this. Moreover, our wider data make evident that extension systems continue to provide limited support to boosting women’s productivity, despite so many women farming and men off in distant jobs.

The transforming cases help to shine a light on the positive contribution of gender equality to economic growth identified by macroeconomic studies. Gender roles and norms greatly shape the context for development and who benefits. We learned that there is real value in reaching out to hear from diverse social groups about the processes of change that they see shaping their lives and community. Where we received consistent reports that their community was on a strong path, we found a normative climate matched by resources that enabled both women’s and men’s agency to take off and powerfully reinforce one another.

This research is part of the CGIAR’s GENNOVATE research initiative. Patti Petesch and Lone Badstue are with the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), and Shelley Feldman is with Cornell University.

The post What can Positive Deviance reveal about gender and social change? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

October 12, 2018

Audio summary (5m) of this week’s FP2P posts

Here’s your potted guide to this week on the blog. I’m just wrapping up in Mexico, and have some fascinating material on its current political transition, among other things, ready to turned into blog fodder. More on that next week.

http://oxfamblogs.org/fp2p/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/wb-8-Oct.m4a

The post Audio summary (5m) of this week’s FP2P posts appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

October 10, 2018

I need a survival guide for conferences. Anyone got one?

rages against people (OK, men) who insist on stating the blindingly obvious at great length, in obscure academic jargon; a twitchy need to check emails and twitter feed every few minutes; sudden enthusiasms and exhaustions. I seem to be especially prone to erratic behaviour on the 1st day, then calm down a bit after that.

Anyone recognize this? Hope so, for purely selfish reasons. Assuming that I am not the only one who experiences conferences as an ordeal, what would be some useful advice for how to attend and get the most out of them? Here are some questions I need answered:

Socializing v working: if the conference runs over several days, the evenings are good times to unwind, get to know people socially etc. But should you drink and stay up late even if it means you have a brainfade by 2pm the next day?

Self care: How do you make sure you get enough sleep in overheated hotel rooms? Should you go running in the mornings, even if it means you’ll feel knackered later on. And how do you avoid mindlessly scoffing the conference pastries?

Annoying people: Should you force yourself to listen to people who really irritate you, as they often have useful things to say (at least I assume they do – I haven’t cracked this yet)? And if you can’t stand it any more, are people wise to the trick of clamping your lifeless phone to your ear and talking into it as you leave the room, pretending that it was on vibrate and someone has called?

Boring speakers/presentations: Do you give up on them and go into standby mode to save energy, or gamely try to find something useful in every contribution?

Pacing Yourself: If you’re not an extrovert, and so find the constant interaction of conferences deeply draining, how do you recharge your batteries/find personal time? Is it OK to chill with mates at lunch/coffee, or should you diligently network with strangers at every break?

Pacing Yourself: If you’re not an extrovert, and so find the constant interaction of conferences deeply draining, how do you recharge your batteries/find personal time? Is it OK to chill with mates at lunch/coffee, or should you diligently network with strangers at every break?

Going to sleep: Is it technically possible to nod off, but look convincingly like you are just listening with your eyes closed?

Listening v Talking: I know we should be listening deeply to each other, and there’s nothing more annoying than watching people preparing their own remarks instead of paying attention to the speaker, but my male brain struggles with multi-tasking: if I genuinely listen to what is being said, I find it hard to shift gear and then speak. How do you get the balance right?

Laptop etiquette: Is it rude and unacceptable to answer your emails and tweets in the meeting, or a perfectly reasonable response to presentations that are either bad or just not relevant to you? After all, as you sit there, the work is piling up in your inbox. If it is uncool, how quickly can you reasonably nip into the conference room while everyone else is registering/having coffee, and bag a seat next to the wall (preferably with a power socket) where no-one can see your screen?

Hidden Power: If it’s a decision-making conference, eg on a future research agenda, how do you work out where decisions are actually being made on the next phase of a research programme? If you’re not in the room for that, but you still want to influence the decisions, is it better to suggest a dozen things and hope that one sticks, or go into advocacy mode and just keep banging on about the same issue to try and browbeat them into submission?

I’d welcome your answers and additions, as always.

And here are some previous conference rants on international conferences, a particularly bad EU conference and why we need a war on panels. Which suggests that another survival strategy is writing snarky blogs about the conference you are currently sitting through…..

The post I need a survival guide for conferences. Anyone got one? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

Putting Gender into Political Economy Analysis: why it matters and how to do it

Guest post by Emily Brown of Oxfam GB (left), and Rebecca Haines (right) and Tam O’Neil of CARE

International UK.

International UK.

For many development professionals, political economy has become the gold standard of foundational analysis for programming. It helps us to understand how power and resources are distributed in a society or sector and is important for ensuring our programmes and campaigns avoid cookie-cutter technical solutions and are designed for real world impact.

This is good news. Or it would be if political economy analysis approaches and products did not overwhelmingly ignore one of the most pervasive systems of power in society – gender relations.

Political economy analysis ignores gender by accident and by design

There are two main reasons why political economy analysis misses gendered power:

Accidental oversight of women as agents : Political economy analysts look for who has influence now and tend to find elite men, because they have visible or typical forms of political and economic power. We then devote the bulk of our analysis to how male power-holders behave and why. Women are mostly invisible, or they are included as victims, passive recipients and/or ‘vehicles’ for other development outcomes e.g. improved child nutrition – and this is then how they feature in programme design.

Deliberate oversight of gendered power and its implications: Many political economy analysts

subscribe to the view that getting things done in the ‘real world’ means understanding and finding ways to work within existing systems – patriarchy and all. They rarely see identifying potential for transformation of the system as their role. This perspective limits the use of political economy analysis for good design and allows political economy analysis to put limits on the programmes we design.

subscribe to the view that getting things done in the ‘real world’ means understanding and finding ways to work within existing systems – patriarchy and all. They rarely see identifying potential for transformation of the system as their role. This perspective limits the use of political economy analysis for good design and allows political economy analysis to put limits on the programmes we design.In our experience, political economy practitioners often resist the suggestion that their analysis should identify potential change-makers, including those with less visible power who want to fundamentally challenge the status quo. They argue that political economy analysis is a neutral or value-free tool for understanding how things are, not how they should be. We contend that focusing only on how to use male-dominated sectors or systems, and not on how to change them, is a normative position – and one that assumes the analyst sees clearly how things are.

By privileging this kind of analysis, we as a sector collectively prioritise making the wheels turn in existing systems. While starting small and making achievable gains is a reasonable approach, political economy tools often make us feel we can stop there, and don’t help us to critique unjust systems and develop a strategy to change them. Ironically, this makes us less political!

Three reasons to integrate gender and political economy analysis

In the ideal scenario, development practitioners use analysis at the beginning and throughout programming to inform design, implementation and learning. Practitioners benefit in three main ways when they recognise gender as a universal and fundamental power structure in their political economy analysis.

Diagnose poverty and inequality holistically: A gender lens opens our analysis to how political and economic systems privilege or disadvantage different groups based on their identities or other characteristics, including sex, gender, age, class, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, disability, marital or citizenship status and geographical location. These systems shape the opportunities, choices and well-being of different people differently, and they also affect the effectiveness of any intervention or reform for different groups. For example, economic development programmes rarely recognise the existence and costs of unpaid (domestic and care) work, its effects on labour force participation, and the role of policy and social norm change in redistributing unpaid work and creating fairer and more efficient economic systems.

Avoid reinforcing power relations that exclude and harm: A gender lens alerts practitioners to whether their planned approach is likely to reinforce systems that reproduce inequality and oppression and/or undermine groups in the process of renegotiating access to rights and resources. For example, cash transfer programmes that fail to recognise intra-household power relations can ingrain women’s subordination and dependence, limit their options and expose them to abuse. Agricultural programmes that fail to engage with legal, customary and cultural barriers to land ownership not only deliver limited practical gains for poor communities but can contribute to land conflict, inefficient land use and women having fewer economic options.

Identify new pathways and agents of change: A gender lens sees women and other traditionally excluded groups as potential agents of progressive change and looks at what sources of power they do have and how these might be bolstered. For example, women’s rights movements are the most important factor in getting government to recognise and promote the social and legal status of women as a group, whether this is women’s constitutional equality, equality in the workplace, action to end violence against women, or special measures to increase women’s political representation. And though still often excluded from peace negotiations, women’ participation is critical for sustainable peace.

South Sudan

Four ways to integrate gender and political economy analysis in practice

Gender is about more than women. It is about gendered roles, expectations and power relations that affect people of all genders and sexual orientations. Below we focus on women, however, to make visible the largest group facing universal and deliberate exclusion based on their sex and gender, and to create ways to include and centre other groups invisible in political economy analysis.

Building the skills and confidence to actually do this kind of analysis is vital, but to date there is little concrete guidance on how to do a gendered political economy analysis. To help fill this gap, the Gender and Development Network’s Guidance Note for Practitioners on Putting Gender in Political Economy Analysis provides a worked example of how to integrate gender in the four steps in a typical political economy analysis. These are:

Make analysis participatory and inclusive: Political economy analysis is much more likely to be relevant, understood, used and updated when as diverse as possible a group of programme staff and partners produce it themselves. And our analysis is strongest when women participate in producing it, both female staff and women in the communities we work with. We also need to be mindful of how intersecting identities shape different women’s experiences and the power relationships amongst the women sharing their intelligence.

Think differently about stakeholders and their power: Purposefully map people with less obvious or official sources of power, and look at how invisible sources of power (e.g. social norms, public perceptions, institutional cultures) affect the position of different stakeholders and their ability to act. Including different views in the process of stakeholder mapping can expose blind spots and untapped sources of power and support for progressive change. For example, consulting with women-led organisations may identify the collective power of women’s producer associations in otherwise gender-blind market trader ecosystems. The collective power of workers in predominantly female industries, such as the Vietnam’s garment sector, has the potential to increase wages and extend labour.

Think differently about people’s motivations and behaviours: Consider how social, political and economic factors affect the motivation and behaviour of different groups of women and men. Doing so helps us to better understand how gender affects how people behave, the likely reactions of different people to programme activities, and the probability of positive change. For example, to increase access to justice we need

an analysis that includes how different women experience the justice system (state and non-state) and the factors that make it more or less likely that they will use it and get a fair outcome.

an analysis that includes how different women experience the justice system (state and non-state) and the factors that make it more or less likely that they will use it and get a fair outcome.Think about women when identifying entry points and realistic pathways to change: The point of political economy analysis in development programming is to understand the underlying causes of a given problem and to identify change processes that are strategic and feasible given prevailing conditions and resources. Integrating gender means considering how an intervention will affect different groups of women and men. It also means considering how women might be supported to drive social, political and economic change, rather than be passive recipients of new rights, opportunities or resources.

Our Guidance Note aims to give practitioners ideas of how they can go about a gendered political economy analysis. But the tools we use matter much less than the process of analysis and how we use what’s revealed in our programme design, implementation and learning. Even trialling a small change – such as choosing a women’s rights organisation or expert to advise us – can lead to significant unanticipated and positive ripple effects in our work. Oxfam’s collaboration with the Women’s Budget Group to deepen the gendered analysis in its Inequality campaign has sparked the development of numerous other gender responsive budget tools and campaign connections. Doing the analysis repeatedly in order to understand and adapt to change over time also reveals new dimensions to the picture – and helps us to develop our gendered muscle memory. Ultimately though, the first, and most important, step is to want to try it. Let us know how you get on!

The post Putting Gender into Political Economy Analysis: why it matters and how to do it appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

October 9, 2018

How Bring Back Our Girls went from hashtag to social movement, while rejecting funding from donors

part of the Action for Empowerment and Accountability research programme

In a world where movements appear and fizzle out just as they are getting started, Nigeria’s Bring Back Our Girls (BBOG) movement is an exception. Meant to be a one-day march in 2014, it has now entered its fourth year and is waxing strong. What’s more, it has done so partly by rejecting funding from foreign aid organizations and supporters. Why?

The BBOG movement erupted in April 2014 following the abduction of over 200 schoolgirls from Chibok Secondary School, Northeast Nigeria, by the Boko Haram Islamist insurgency group. The group organized a public protest on 30 April in Nigeria’s capital, Abuja. It was meant to be a one off, but then something happened.

A man from Chibok, an abductee’s relative, knelt and begged the crowd: “don’t leave us; if you do they (the government) will forget us”. On the spur of the moment, former minister Oby Ezekwesili announced: we will stand with you until your kids come back! Since then, the BBOG has met every day at the Unity Fountain in Abuja. It has also staged some 200 protests within and outside Nigeria.

Not a flash in the pan

There were many reasons to expect the BBOG movement to live up to its initial aim and be short-lived. One is that it was taking place in a fragile and conflict-affected setting, where the pressures of daily survival make social causes a lower priority for many people. Government helplessness, especially in the face of insurgency, makes membership of pressure groups frustrating.

There were many reasons to expect the BBOG movement to live up to its initial aim and be short-lived. One is that it was taking place in a fragile and conflict-affected setting, where the pressures of daily survival make social causes a lower priority for many people. Government helplessness, especially in the face of insurgency, makes membership of pressure groups frustrating.

Another reason to expect the BBOG movement to be a flash in the pan is that its focus was not a recurrent issue but a one-off one: pressure the government to rescue the abducted schoolgirls and bring them back alive and safe. That it was women-led is also not a particularly helpful factor.: in patriarchal and male-dominated societies, women-led movements and protests, if they happen, tend to be shortlived.

Yet the movement trudges along.

Elastic circle of concern

Although the stated aim of the BBOG movement is to pressure the government to confront Boko Haram and bring the abducted Chibok girls back home safely, it keeps redefining and extending what this really means.

When some women were abducted in Bassa, the BBOG printed their photos on large placards and staged a protest – “bring back our girls and the women”. When lecturers of a university were abducted while on fieldwork, the BBOG staged a protest: “bring back our girls and the UNIMAID lecturers”. When Boko Haram allegedly killed a large  number of soldiers, BBOG staged a march, “bring back our girls and don’t bury our soldiers secretly in mass graves”. The list goes on. The Movement then extended its concern to include demand for good governance – shorthand for everything from the provision of safety and security of citizens, to better healthcare, better infrastructure and a better economy.

number of soldiers, BBOG staged a march, “bring back our girls and don’t bury our soldiers secretly in mass graves”. The list goes on. The Movement then extended its concern to include demand for good governance – shorthand for everything from the provision of safety and security of citizens, to better healthcare, better infrastructure and a better economy.

In Nigeria and indeed in most fragile and conflict-affected settings, most of those who join protests are those who have personal stakes: an abductee’s relative, owner of a threatened roadside business, residents of a neighbourhood marked for demolition etc.

By constantly redefining the circumference of their focus, BBOG increases the number of those who have personal stakes and, therefore, willingly join marches or protests. Yet, by keeping the Chibok girl’s abduction at the centre of their discourse but then weaving other contiguous issues around it and extending it to good governance, BBOG demonstrates a single-mindedness and doggedness that endear them to both local and foreign supporters.

The BBOG operates a surprising funding policy: they have so far refused funding support from both foreign and local donors. The leadership argued that once there was money, there would be a struggle for it among them, and their focus would be shifted from pressurising government to sharing money. They also feared that once people (especially politicians) gave them money, they could be seen as being partisan. (There were allegations at the start that they were being used by the opposition to harass the government.)

Relying heavily on donations from members and in-kind support, the Movement does not even have a bank account. They do, however, solicit international news makers (such as Ms Michelle Obama) to openly identify with their cause.

Relying heavily on donations from members and in-kind support, the Movement does not even have a bank account. They do, however, solicit international news makers (such as Ms Michelle Obama) to openly identify with their cause.

A lot is being said about the shrinking civic space in conflict-affected and authoritarian settings. However, a closer attention to the strategies of civic actors may reveal two things: one, that the civic space is not really shrinking but changing, and two, the creative ways in which civic actors are responding to these changes – the creativity that explains their resilience.

This post is based on research by Ayo Ojebode (University of Ibadan, Nigeria), Dr Fatai Aremu, Dr Plangsat Dayil; Dr Martin Atela & Prof Tade Aina, commissioned by the Partnership for African Social and Governance Research (PASGR)

The post How Bring Back Our Girls went from hashtag to social movement, while rejecting funding from donors appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers