Duncan Green's Blog, page 80

December 3, 2018

It’s time to change up From Poverty to Power – Know Anyone Who Can Help?

readers may have noticed, In recent years I’ve been inviting more guests onto the blog, but have always struggled to find the time and resources to do it properly. Now the Ford and Hewlett Foundations have kindly stumped up some funding to allow us to employ a half time person to work with me and our tech guru Amy Moran to diversify the range of voices on this blog and zap up our use of technology beyond my hopeless vlogs and slightly less hopeless (I think) podcasts. They might even find us some new cartoons……

Could that person be you, or someone you know? If so, read on. Here’s the blurb (application details here; deadline 16th December, so you’ve got to move fast):

‘The ‘From Poverty to Power blog’ is seeking to diversify and bring in more global views to help influence and shape international development debate and practice.

What we are looking for:

Thoughtfully provocative and passionate about debating poverty and injustice? We need you! You believe in diversity of voices about development that benefits everyone. You excel at social media and in-depth interviewing. You’re a mega-talented connector and can spot a good story where others don’t. Getting people to share their voices and wisdom gives you a kick. Making this heard by tens of thousands globally is what you live for.

We are looking for someone deeply committed to ensuring diverse global voices are heard widely and influence global development debates.

You have experience in editing, commissioning and creating different web formats (audio, written, video). You have a passion for finding a story and a keen eye for detail.

You can manage your own workload without close supervision and work independently on making decisions and problem solving on routine issues.

You are creative and innovative in your approach to finding and developing a story, thinking about different media types, with a sound knowledge of international development issues.

You are creative and innovative in your approach to finding and developing a story, thinking about different media types, with a sound knowledge of international development issues.

Key Responsibilities

Work closely with Duncan Green (Senior Strategic Adviser), to commission, interview and create blogs, podcasts and videos from the global south, with a view to contribute more diverse views to debates and discussions around international development.

To work with the Digital Communications Manager (Amy Moran) to search/aggregate the best

international development content from around the web.

To work with and implement new ideas for types of content/debates/discussions.

To work with the Digital Communications Manager to create online surveys assessing audience engagement with the blog, and make recommendations for improved performance based on them.

To assist in the experimentation of new online platforms and communities to extend the reach of the blogs/podcasts/videos and foster discussions outside of FP2P.’

Interested? If so, here’s the application form again. Deadline 16th December. Clock’s ticking.

The post It’s time to change up From Poverty to Power – Know Anyone Who Can Help? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

December 2, 2018

Links I Liked

Ht Ellie Levenson

What Do African Aid Recipients Think of Charity Ads?

How to run a ‘book sprint‘ that enables a group of authors to write a book in 3-5 days

Bangladesh’s gender wage gap is the lowest in the world (ILO) ht Naila Kabeer

‘Growing grassroots activism among Rohingya in the camps – including a network of self-funded schools – is driven by a generation of refugees who came of age in the camps as well  as by more recent arrivals who graduated from school before fleeing Myanmar.’

as by more recent arrivals who graduated from school before fleeing Myanmar.’

Adam Smith looks like he might finally make it

Identity Politics and the Political Marketplace. Serious helicopter thinking from Mary Kaldor

‘there is a proliferation of orphanages in tourist destinations. People see visiting an orphanage as part of a tourism experience like going on safari.’

Here’s a metaphor for me trying to learn anything involving IT

Even though it is apparently being circulated among Tory MPs, this clip from a 1992 comedy bears no resemblance to any current or former members of the British Government. Got that? None at all…

The post Links I Liked appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

November 30, 2018

Audio Summary (16m) of FP2P blogposts, week beginning 26th November

Longer than usual summary – 16 minutes. Not sure if the week’s posts were particularly content-rich, or I was just feeling chatty…..

The post Audio Summary (16m) of FP2P blogposts, week beginning 26th November appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

November 29, 2018

How can Universities get more activists to take-up their research?

Another day, another coffee conversation about how to ensure that academic research has impact beyond the ivory

They’re only a few miles away, so why don’t we read more of their stuff?

tower/dreaming spires. This time it was with Duncan McLaren, who has just started as a fellow Professor in Practice (is this A Thing now?) at the Lancaster Environment Centre and has been asked to look into how its research can get greater pick-up among activists. Some random thoughts, and I will try to be a bit more constructive this time, given how many people were provoked by my last post on this!

Writing v Talking: Looking around me at the LSE, I suspect that academics exert a lot of their influence not through publishing, but in person, by being invited to talk to officials and politicians, speaking and networking at events etc. If that’s true (surely it could be researched?!), then universities should rethink the kind of support they give to researchers. Elevator pitches? Cocktail party skills, like how to break in on a conversation involving your victim target decision maker? Everyone should be required to listen to Babu Rahman.

Some disciplines are better at this than others: which are the most effective policy influencers and is there anything we can learn from them? Why do so many people persist in listening to orthodox economists? Is it because they (sort of) claim to predict the future? Or use lots of equations to make themselves look like real scientists? And what could we learn from those real (natural) scientists? After all, most UK Government departments have influential chief scientific advisers, but I don’t know of any that have a social science adviser.

Riding the Wave v Creating it: One thing many academics and activists have in common is a kind of intellectual totalitarianism – they prefer complete, tidy solutions, not messy compromises. Whether on climate change or migration, both sides’ attempts to influence decision makers sometimes boils down to little more than ‘why can’t you see that I am right and change your ways?!’

Riding a metaphor

But influence often comes from riding waves, not making them – responding to critical junctures, or spotting opportunities created by processes intended for entirely different purposes (eg my colleague Jean-Paul Faguet argues that decentralization in Bolivia led to the downfall of traditional political parties). You can’t predict these waves; everyone can see them in hindsight – but the interesting bit is in between: how soon can you spot new opportunities opening up and jump in?

Timescales: The contrasting rhythms of advocacy and research are often a problem. Research takes time; advocacy needs to respond rapidly to windows of opportunity. When food prices started to go haywire at the start of this decade, we did some initial work with IDS that earned us a 3 year DFID grant for further research. Unfortunately, the advocacy spotlight moved on, but we were obliged to keep one of our smartest researchers running a programme that worked fine for IDS, but found little demand within Oxfam.

Some funders have tried to push researchers into being more responsive by attaching ‘rapid response’ budget lines to research grants, but such are the career incentives to staying on the treadmill of academic publication that these often go unused.

Caution and fear of mistakes: Great importance is attached in academia to not getting caught out. A single public take down resonates for years, permanently blighting a reputation. It’s a nasty macho side to academia that prompts people to add lots of defensive caveats, and speak in academic code rather than the vernacular, undermining their ability to communicate.

Precision v Clarity: A lot of academic writing is about being as precise as possible in definitions and use of

Typical seminar format

language. But bringing about change sometimes requires constructive ambiguity – fuzzwords that a diverse coalition can get behind, even if they understand them in different ways. That’s what political slogans are all about. The search for precision can undermine this effort or make messages more inaccessible, when it comes across as hair-splitting rather than productive clarification.

And some more standard things I bang on about:

Involve your targets: the worst (and probably most common) approach is to write your paper. then asl ‘right, who should read this?’ and send it to them. That kind of extreme supply-led approach is much less effective than involving your ‘targets’ in designing the research, commenting on drafts etc. That will both get their buy-in, and ensure the end result might be vaguely relevant to them.

Open Access: This shouldn’t need repeating, but no-one outside academia pays to read articles. If you publish behind a paywall, you’re essentially showing two fingers to the non academic world and saying ‘Don’t care – I only write for my peers’.

Building Bridges

Ok, so how can we improve matters? Neither academia nor NGOs are monoliths. Sitting uncomfortably in the overlapping bit of the Venn diagram are the unfortunately-named ‘pracademics’. On the NGO side, there are PhDs who still keep reading and networking with their academic colleagues; on the academic side, people do consultancies or volunteer their services and advice to a range of activist organizations. How do we expand and support them?

Recognition: how could we do this in a way that pushes back against the pressure to feed the journal beast in academia, or the cult of busyness in the NGOs?

Training and immersion: Pracademics could get 2 weeks a year to catch up on their reading or write a paper based on their experience, perhaps based at and mentored by a sympathetic university. On the academic side, anyone claiming to be an activist should spend the same amount of time actually trying to influence policy, for example in an NGO advocacy team.

Other suggestions?

[Thanks to ace pracademic Jo Rowlands for comments on an earlier draft]

The post How can Universities get more activists to take-up their research? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

November 28, 2018

How can Activists get better at harnessing Narratives for social change?

. People concerned about climate change rightly say we need to cut down on our air miles, but there’s a cost – a webinar is nowhere near as good as a face to face meeting with real people.

But despite the clunkiness, they can still be thought-provoking. Recently, I dialled in to a webinar where Oxfam teams in Peru, Uganda, South Africa and Niger were swapping notes on how to think and work around narratives, in particular the kinds of narratives being used to close down civic space in countries around the world.

The argument is this: Narratives are being used to close civic space by delegitimising civic actors and activism (think ‘enemies of the people’ or ‘foreign stooges’). Our hypothesis is that they can also open it. To do that we need to

Understand the deeper dynamics underlying those narratives

Bring new and old civil society, young people, academics, investigative journalists and other allies together to collectively understand what we are up against

Reflect on how to renew and strengthen connections to broader society

Begin to weave and test more inclusive & compelling narratives

Strengthen a new grouping to stand behind those new narratives

Lots of really interesting and inspiring work is already under way. In Oxfam, the most advanced seems to be our Peru team, which has worked face to face and online with young people’s collectives to develop new narratives that interweave topical issues, facts and data with humour and pop culture references, all with a Peruvian flavour. More (in Spanish) on the funky actua.pe website.

From the actua.pe website

I suspect people get a bit fed up with me in these conversations because I am a ‘what abouter’. People set out what they are doing, which is pretty impressive (eg rigorously collecting and comparing the main anti-civic space narratives in a given country) and then I say ‘fine, but what about …..’ That’s handy in opening up conversations like this, but you need to get rid of me for the subsequent conversation, when you start narrowing it down to what you actually want to do.

So here are my top ‘what abouts’:

Messenger v Message: the conversation was about narratives as A Thing, with their own nature and identity. But a narrative needs narrators – if you’re trying to influence people, it’s often more important whose mouth something comes out of, than what the words actually say, as the great recent Violence Against Women example from Moldova showed. Once we establish the target audience for a narrative, (eg whether it’s decision makers, or some sector of the public), shouldn’t our first question be ‘who do they respect/fear/find persuasive and can we get any of those people or institutions to speak up?’

Defence v Offense: which is more effective – trying to counter/neutralize negative narratives (‘Those troublesome CSOs are all corrupt and/or political and/or agents of foreign powers’) or coming up with entirely separate narratives to replace them (‘CSOs built your schools; Gandhi was an activist’)

How rigorous can we get? The topic lends itself to hand waving – vague assertions of what narratives are and how to change them. What would a rigorous approach look like – should we be using market researchers to test different proposed narratives on the target audience (rather than just guessing or asking our allies)? How do we know whether our narrative-shifting is being successful or not?

are the old ones the best ones?

New narratives v old: we seem to be devoting a lot of effort to working with allies to come up with new narratives. But what about old ones? The activists in El Salvador’s 1970s revolutionary movement used the Biblical story of The Exodus when discussing peasant evictions – they got it immediately because the story was so deeply rooted in their Catholic identity (Alex Evans captured the value of religious narratives brilliantly in The Myth Gap).

Or should we try and follow one of the 7 basic plots for nearly all stories (since you asked, overcoming the monster; rags to riches; the quest; voyage and return; comedy; tragedy; rebirth), because they are the ones that have been shown to have resonated over the centuries?

Among my LSE students, who largely come from local elites all over the world, I’ve realized that global pop culture is a rich source of shared narratives – Harry Potter, Lord of the Rings, the Matrix, Hunger Games, even Mad Max (if you’re talking Climate Change dystopias) all provide instant resonance and recognition.

By comparison, I worry that our perfectly sensible, evidence based narratives like ‘tax justice’ and ‘rights based approaches’ sound dry and remote. Do they are just widening the gap between organized civil society and the rest of us? Plugging in to memes, humour, pop culture and local historic/cultural icons can help embed these ideas, but maybe we should start further back and stick to more basic narratives of right and wrong, fairness and justice, without all the policy recommendations?

Best line of the webinar? ‘I’m sorry, but English is my 6th language’ (from a woman who had just expressed herself in English with the utmost clarity). Love it.

And here’s what a conference call would be like in real life

The post How can Activists get better at harnessing Narratives for social change? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

November 27, 2018

Working With/Against the Grain, the case for Toolkits, and the future of Thinking and Working Politically

Working With or Against the Grain?

In a way, this is a reworking of the reformist v radical divide. Should TWP focus on understanding local institutions and find ways to work with them to achieve progressive change, or should it challenge those institutions, eg on norms, or the exclusion of particular groups? ‘TWP can reduce conflict by doing deals with elites, eg in the Middle East, but that’s inclusion going out of the window.’

This is particularly relevant because of the way the world has changed since those early conversations in 2013. The crackdown on civil society and the increasing assaults by political leaders on the rule of law and democratic institutions (Duterte in the Philippines, Bolsonaro in Brazil, Magufuli in Tanzania) have made ‘whose grain are we talking about here?’ a more pressing question. TWP was conceived on the front foot – a world where political and social progress was the aim. We need to think about whether TWP in a political downturn looks different – defending previous gains rather than seeking new ones; helping to protect those at risk; changing our language,  practices and alliances to reflect the fact that aid and foreigners are less welcome (should some organizations even try to go back to the kinds of covert support for the good guys they practiced during the anti-apartheid struggle and the Central American civil wars?)

practices and alliances to reflect the fact that aid and foreigners are less welcome (should some organizations even try to go back to the kinds of covert support for the good guys they practiced during the anti-apartheid struggle and the Central American civil wars?)

But working against the grain can be a conflict-ridden exercise, and while conflict may indeed often be an effective driver of change, aid donors don’t show much appetite for stoking it, probably with good reason (back to legitimacy and risk). In practice, whatever the intellectual argument, I think it is likely that official donors will default to working with the grain, and NGOs (at least the more radical ones) feel more comfortable working against it.

And whichever path you choose, you may well need the same skills – context analysis, power mapping, building coalitions and seizing windows of opportunity as they open up.

The Case for Toolkits

I don’t normally get excited about a discussion on toolkits, but I did this time. Why? Because I’ve had a nagging feeling that I was being too dismissive of toolkits, and this conversation helped me articulate a better way of thinking about it.

The aid sector works through tools – guidance documents, ‘how to’ checklists etc. For ideas to spread, they need to be codified so that they can easily be adopted by new entrants or people who are not passionate advocates, but just doing their jobs. If you refuse to produce toolkits, you are likely to remain pure but marginal.

The issue is what kind of tool. Some tools empower/encourage people to think harder, others disempower/make people think less. I’m not a big fan of sports metaphors, but I liked the comparison with Pep Guardiola’s doctrine at Manchester City (as reported to us) – you need rules for what players do in the first 2/3 of the pitch, but in the last 1/3, it’s all about instinct. The standard TWP cliché is that you need ‘a compass not a map’, but you need some training on how to use a compass well – that’s the kind of toolkit I’m talking about. Guidance not  checklists/straitjackets.

checklists/straitjackets.

My rule of thumb is give people questions to ask, and lots of case studies, but don’t tell them what answers to look for – that’s the last 1/3 of the pitch. In the case of the ‘second orthodoxy’, it feels like the tipping point, when good tools become bad, is somewhere around the point when we say ‘right, let’s draw up our Theory of Change’. Thinking stops, and everyone obsesses on drawing a super-complicated diagram that no-one who was not in the room can ever understand.

Crystal Ball: Where does TWP go from here?

Where next for TWP? How to use TWP to ensure the sustained success of TWP? In his great book, Limits to Institutional Reform in Development, Matt Andrews summarizes the stages of paradigm shifts in political thought as:

Deinstitutionalization: encourage the growing discussion on the problems of the current model

Preinstitutionalization: groups begin innovating in search of alternative logics, involving ‘distributive agents’ (eg low ranking civil servants) to demonstrate feasibility

Theorization: proposed new institutions are explained to the broader community, needing a ‘compelling message about change.’

Diffusion: as more ‘distributive agents’ pick it up, a new consensus emerges

Reinstitutionalization: legitimacy (hegemony) is achieved.

Seems to me like we (by which I mean the broader group of second orthodoxy approaches) need to think about the last two bullets. In our governance bubble, we may think it’s already the orthodoxy, but it certainly doesn’t look like that in other sectors (health, education, infrastructure) – plenty of diffusion still to push for.

But what about reinstitutionalization? Can we make TWP the standard, without it becoming dumbed down, like happened to the logframe? Probably not, but we can try and minimize the erosion by creating the right (empowering) tools, and capturing the institutions of training and replication, where new groups of ‘change makers’ are formed. One of the institutional reasons for the flourishing of PDIA and the Political Economy Approach has been the summer schools and training courses run by Harvard and The Policy Practice/ODI respectively – we need to do the same thing for TWP.

But what about reinstitutionalization? Can we make TWP the standard, without it becoming dumbed down, like happened to the logframe? Probably not, but we can try and minimize the erosion by creating the right (empowering) tools, and capturing the institutions of training and replication, where new groups of ‘change makers’ are formed. One of the institutional reasons for the flourishing of PDIA and the Political Economy Approach has been the summer schools and training courses run by Harvard and The Policy Practice/ODI respectively – we need to do the same thing for TWP.

And finally, back to decolonization. Whatever steps we take to institutionalise TWP should be part of ‘handing over the stick’ to practitioners in the Global South, whether aid workers, activists or civil servants. That should shape the things we fund, the tools we create and disseminate and the way we design training and the kinds of ‘project in a box’ TWP social franchising that could really spread.

Two longish posts – but it was a fascinating and productive day. Over to the participants and others to add their bit.

The post Working With/Against the Grain, the case for Toolkits, and the future of Thinking and Working Politically appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

November 26, 2018

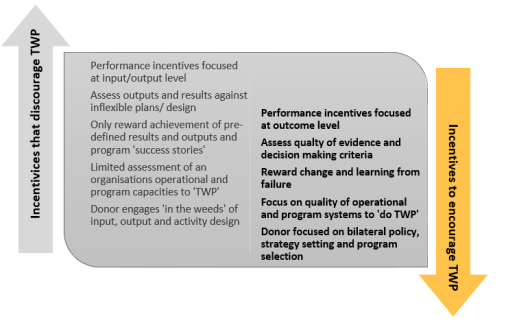

Thinking and Working Politically – why the unexpected success?

over the last 5 years (first sighting, November 2013 and this meeting in Delhi), and pondering next steps. Too much to say for a single post, so this will be spread over the next two days. All under the Chatham House Rule, so no names, no institutions.

TWP is part of that family of approaches & acronyms that includes ‘Doing Development Differently’ and ‘Adaptive Management’, which Graham Teskey has jointly labelled (somewhat prematurely in my view) a ‘second orthodoxy’ in aid. He identifies the common components of that orthodoxy as:

Context is everything – so political economy analysis is central, and not just at planning stage

Best fit not best practice

From blueprint → flexible, responsive, adaptive programming

Real-time learning

Long-term commitment

That 2013 post concluded ‘This looks like an incipient ‘community of practice’, with the focus on the practice.’ Fast forward five years, and the CoP exists, with a website and a burgeoning list of publications.

Thinking v Working: There is a common lament that there’s been lots of activity on thinking politically – researchers churning out papers, big books from assorted gurus; but the working bit is lagging behind. I’m not sure that is true – it may be down to an overly crude idea of how change happens in the aid sector: someone has a good idea → another person turns it into a pilot to test it → researchers measure the impact and if results are good, the approach spreads, if bad, it is abandoned. Job done.

But what actually seems to happen is more like lots of talk and intellectual branding + a few iconic case studies → a new bubble/fuzzword → partial adoption and a lot of hype claiming to be doing TWP, adaptive management etc, but not really doing anything new, making it well-nigh impossible to know what on earth is going on, let alone ‘test’ anything. See frustrated practitioners’ recent post on sorting out hype from substance on adaptive management.

In addition, the transition from new idea to isomorphic mimicry (when everyone starts sprinkling the relevant phrase over every funding application or project report to make themselves look funky and cutting edge) is shrinking. Fad grazers prowl the blogosphere, detecting new buzzwords, sifting useful from stupid, and then start sprinkling them liberally over their powerpoints and project documents. You now only have a couple of years (at most) to establish and develop a good idea before a tidal wave of isomorphic spin and hype engulfs you.

Why TWP’s Unexpected Success?

The fact that TWP/DDD/AM etc have generated a hype bubble in the aid sector is actually pretty surprising, given the countervailing forces working in the opposite direction (politicians eager to minimise risk, the narrow focus on short term, easily measurable results and value for money). We could easily have ended up in an aid sector consisting entirely of bednets and vaccines, where all that politics and power stuff is the abandoned relic of a previous era.

The fact that TWP/DDD/AM etc have generated a hype bubble in the aid sector is actually pretty surprising, given the countervailing forces working in the opposite direction (politicians eager to minimise risk, the narrow focus on short term, easily measurable results and value for money). We could easily have ended up in an aid sector consisting entirely of bednets and vaccines, where all that politics and power stuff is the abandoned relic of a previous era.

How did that happen? If I’m honest, I don’t think it’s because of an overwhelming body of evidence, but because TWP itself goes with the grain of reality. The language of TWP reflects the experiences of aid people – they know this is how the world works, how change happens. Now, like the character in Moliere who gets terribly excited when he is told that he has been speaking in prose all his life, what they instinctively feel to be right is being validated by ideas, research, jargon.

What evidence exists (summarized here) is largely of the case study kind, rather than some attempt at an econometric slam dunk (TWP improves X by Y%). I much prefer that – you learn a lot more, and in any case, the sceptics are not persuaded by that kind of number crunching (climate change, anyone)? Instead we need compelling stories and narratives, and I think TWP is on much firmer ground there.

That also comes back to whether TWP should become a ‘product’ or an ‘approach’ – an approach is a way of seeing the world, more like an academic discipline. No-one is expected to ‘prove the effectiveness’ of history or anthropology via an RCT.

But unexpected success also creates a risk – you get noticed. Tall poppy syndrome. Overclaiming/overselling happens a lot in the aid sector, and I think we need to avoid it in TWP – we’re already making progress, so there’s no need.

Familiar Themes with new twists: Ages ago, Tom Parks identified a spectrum of approaches from reformist to radical. Some of those engaged in ‘doing development differently’ are looking for better tactics with which to bring about the reforms they want within the existing system. They are more interested in pulling levers and getting stuff done, and not that interested in all that talk of inclusion and transformation. Others see the ‘politically’ in TWP as a call to something more revolutionary (or transformational as we call it nowadays).

call to something more revolutionary (or transformational as we call it nowadays).

That is still the case, and there has still not been a serious falling out between the reformists and the radicals, although the latter have got pretty frustrated over the way gender keeps dropping off the TWP agenda. That remains a challenge, but one that is acknowledged and generating good research and advice. What is at least as worrying, from my point of view, is the lack of ‘decolonization’ (more on that in this paper by Jonathan Fisher and Heather Marquette). TWP remains an overwhelming White, Northern (if you include White South Africans and Aussies) gig; no-one in the room could think of a TWP programme that was not initially drawn up by white outside ‘experts’, even if the programmes subsequently succeed in ‘indigenising’. Changing that will require spreading the message, letting go of control, and maybe offering some limited support for experimentation outside the donor home countries.

That comes into sharp relief when we talk about legitimacy: when is it OK for outsiders to try and change institutions and policies in another country? INGOs partially answer that by working with and through local partner organizations; but bilateral donors carry out the policies of their governments – the potential infringement of sovereignty is much clearer. I don’t think I’ve ever heard this adequately discussed in a TWP setting, but there were some useful comments this time around: ‘Are we trying to strengthen institutions and structures, building political resilience, or get specific wins and results by telling them what we think they should be doing. That’s when we cross the line on legitimacy.’

Another familiar complaint that has yet to be addressed is the pressure to spend: from a donor perspective, one of the problems with TWP is, paradoxically, that it does not require much money – it needs lots of time, brain power, facilitation, knowledge and local antennae, but by aid standards, none of those cost that much. But staff are under enormous pressure to hit their ‘burn rates’ or risk being punished for underspending. Aid officials complain that they are so busy spending money (a very bureaucratic, and time consuming process) that they have no time left to think any more. As one donor staffer put it ‘The last thing you need is a big slug of money that you need to get out of the door. Maybe TWP can help tell me where can I put a large amount of money safely and quickly that is not going to make things much worse!’

Another hardy perennial that surfaces briefly, then disappears back into the talkswamp, is HR. Put bluntly, these kind of changes in approach require different kinds of people to come and work in the aid sector: up to now entrepreneurial, innovative, dancing-with-the-system types have seldom survived the mind-numbing bureaucracy and process-heavy ways of working. The aid sector needs to value different skills and ‘competencies’ when hiring, work out ways to support and retain the mavericks, and rethink its attitudes to rewards and incentives.

That’s enough for now. Please come back tomorrow for Working With/Against the Grain, the case for toolkits and my crystal ball on the future of TWP.

The post Thinking and Working Politically – why the unexpected success? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

November 25, 2018

Putting Positive Deviance into Practice: A brilliant UN Women initiative on domestic violence

a good moment to post this.

As part of my scoping exercise on Positive Deviance, I’ve been having some great skype conversations. Monique Sternin put me in touch with Ulziisuren Jamsran (Ulzii) in Moldova, where she runs a 22 person team for UN Women (UNW) that has been a ‘self-declared innovation hub’ since 2015. She is from Mongolia, and has spent several years in Moldova, having just returned from a period in Palestine. She beautifully captures her role as an institutional entrepreneur ‘I am in the scratching business, scratching from within. UN and UNW offices in Nepal, Palestine, Fiji and Bangkok are all now introducing PD.’

PD helped her team realize that they had been overlooking a huge resource – the agency and voice of women who were survivors of domestic violence. It has transformed UNW’s work. Here’s a transcript of part of our conversation:

‘I heard about PD at the end of 2015and fell in love with it immediately – such a huge opportunity to revamp our work from the perspective of those who we try to serve. PD is not an approach, it’s a total mindset that we bring into everything that we do.

We were lucky to have partner organizations that contained many members from left-behind groups – Roma, women with disabilities, survivors of domestic violence. Because we were close to those groups, we were able to share and engage with these women on the need for innovation. It was fertile ground.

PD was the centrepiece of that innovation discussion. We asked our CSO partners to what extent they worked with survivors of violence themselves; how did they learn from them, what did they learn? The answers were absent. We operated on the basis of the assumption that all the work with survivors had to be incognito – we had never asked the survivors if they could speak up, talk in public. It was totally new for us.

We started experimenting with 4 rural CSOs, including those that ran shelters for women. When we asked survivors if they were willing to speak in public, some said, ‘Why not?’ They were willing to share publicly and tell their stories to other women.

We identified women ready to speak up (‘the PDs’), then we organized one training for them on how to tell empowering stories. We facilitated lots of gatherings between the PDs themselves to share experiences, talk about what works, develop their own initiatives. We fan the meetings ourselves as in order to move as fast as possible. We learned so much, felt so empowered – It was amazing!

Some women also needed briefing about their rights – not every PD had fully overcome GBV and they needed support. But we helped them to start to talk to each other, further access services and network.

Some women also needed briefing about their rights – not every PD had fully overcome GBV and they needed support. But we helped them to start to talk to each other, further access services and network.

The CSOs realized that they need to change their own behaviour when working with PDs. Together with CSOs we learned how much the PDs had to offer, so much knowledge, courage – it was not about empowering them, just helping them to share their empowerment with others.

Our concept has always been about how we empower victims – we have only that one scenario. But then we started to realize how much knowledge they had, e.g. on how to work with victims and survivors. They already had all the solutions that NGOs and the government together with other development actors were trying to design for the survivors. No need! All the knowledge was there. But survivors didn’t recognize the value of their knowledge – they see it as basic experience, because no-one has ever acknowledged it.

By the end of 2016 our PDs were ready for more. NGOs started to gather survivors, but the major part of it was done by the PDs themselves. So many women came forward and started to talk with the survivors, such a high level of trust, an immediate connection. Then the survivors started to ask for assistance – so magical, yet so simple. After 4 months of experimentation, we could not believe the impact – the number of women requesting local support services was up 5 times in 4 months!

We had some data from NGO partners: their annual budget for shelters fell by 30% due to the work of PDs, because fewer women needed to be placed in shelters – women spoke up earlier and so didn’t have to leave their families.

What lessons emerged? It is the trust of the victims and survivors that matters the most. Trust towards those whom they interact with as their first critical step towards asking for services and help. In many instances the offers by the competent service providers are denied simply because they are seen as outsiders, as those who are just doing their work. People see the outsiders and ask ‘what is in it for them?’ ‘They are here today, gone tomorrow.’ PDs helped overcome that resistance.

One GBV Initiative was women survivors writing ‘a letter to my daughter’ – a story with an encouraging ending. We recorded videos of them reading their own letters and put it out on social media. It had a big resonance and encouraged more women to come forward. It’s incredible what impact it can have when it’s not the usual organizations speaking.

[Here’s one example – probably best to have a tissue handy]

[And here are the letters from Rodica Carpenco, Maria Scorodinschi and Natalia Jenunchi, who are also leading the march in the pic below]

We say ‘Positive Champions’ in Moldova not ‘Positive Deviants’, because people don’t like the term, especially in translation!

In 2017 I went to Palestine, and managed to take the PD approach there – it’s a much bigger programme and team. We had amazing results there – the main angle there was through men speaking up on their experiences of stopping violence and early marriage. 10 UN agencies in Palestine are now developing the approach.

We’re working to expand the PD work: e.g. with a tech company (Eon Reality) and a few other partner organizations  (WIN, Inland University) to document behaviour of survivors, and maybe of aggressors, and translate it into VR films to accelerate dissemination of positive behaviour that leads to breaking the violence chain.’

(WIN, Inland University) to document behaviour of survivors, and maybe of aggressors, and translate it into VR films to accelerate dissemination of positive behaviour that leads to breaking the violence chain.’

Apart from how wonderful and moving this is, what struck me was that PD can lead in so many different directions. They could have taken a more technical approach, along the lines of the primary education PD work in Kenya I covered last year, and identified households or communities free of violence, and what could be learned from them. Instead, they looked for deviants among the group of survivors, and something like a community organization approach emerged.

More background on the programme here.

The post Putting Positive Deviance into Practice: A brilliant UN Women initiative on domestic violence appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

November 24, 2018

Audio round-up of From Poverty to Power posts, week beginning 19th November

The post Audio round-up of From Poverty to Power posts, week beginning 19th November appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

November 22, 2018

Book Review: Radical Help, by Hilary Cottam

thousands, often working and thinking along parallel lines to their counterparts in Oxfam and around the world. I just finished Radical Help, a wonderful book by Hilary Cottam, for which the tl;dr summary could be ‘Amartya Sen meets the Welfare State, and tells it to pull its socks up.’

70 years after its glorious beginnings, the UK welfare state is creaking. The problems run far deeper than austerity (although that matters too). It faces social challenges it was not designed for (obesity, precarious work, ageing); there is a crisis of care (ageing, changing roles in the family) and poverty endures as inequality rises.

The welfare state was built around a series of assumptions and ways of working: it fills gaps, the sick can be cured by medical intervention (what about Alzheimers? Obesity?), society is made up of individuals whose problems can be fixed through individual interventions (what about relationships/social capital?).

Cottam believes that the move to ‘New Public Management’ took these original design flaws and made them far worse. ‘We have normalised the idea that for every problem there must be a service’, and given budget constraints and politics, those services are expected to be delivered ever-more cheaply.

Interestingly, the architect of the UK welfare state, William Beveridge, was by 1946 already growing concerned about its direction. He published a third report on voluntary action, in which he voiced concern that he had both missed and limited the power of the citizen and of communities.

Which is where Amartya Sen comes in. Cottam bases her ideas for a revamp of the welfare state on his ideas of capabilities and agency. ‘Our welfare state might still catch us when we fall, but it cannot help us take flight.’ What assets do people have? What do they want to do with their lives (often as families or communities)? Start from there, instead of the individualised ‘culture of lack’.

So far, so rhetorical, but Cottam is a one-woman think-and-do tank, so she rolled up her sleeves and started trying to test her ideas in practice, via Participle, an organization she founded. Most of the book is devoted to an account of five experiments, developing new prototypes for working with families, teenagers, the unemployed, chronically sick and the elderly, building on their assets and desires. The accounts are full of moving stories of the people she encountered and worked with (no space here, because I know that geeky FP2P readers will be clamouring for the methodology, but they really are very good).

So far, so rhetorical, but Cottam is a one-woman think-and-do tank, so she rolled up her sleeves and started trying to test her ideas in practice, via Participle, an organization she founded. Most of the book is devoted to an account of five experiments, developing new prototypes for working with families, teenagers, the unemployed, chronically sick and the elderly, building on their assets and desires. The accounts are full of moving stories of the people she encountered and worked with (no space here, because I know that geeky FP2P readers will be clamouring for the methodology, but they really are very good).

On what look like pretty limited budgets (she doesn’t provide details), Participle developed a set of principles and a design methodology for coming up with new and innovative approaches. They include developing a vision and recovering a sense of purpose (sorely missing from large parts of the modern welfare state); supporting people to grow their capabilities, starting with learning, health, community and relationships (of these, relationships often hold the key to progress on the other 3). Create a sense of possibility in the people you are working with and they will often take it from there.

To put these principles into practice, Participle adapted design thinking, spending lots of time understanding the context and framing the problem/finding the opportunity. That meant finding funding champions (usually local authority leaders willing to take a risk) and putting together a core team. Then came drinking lots of cups of tea on sofas in deprived areas of Britain, getting to know people, and starting to understand from the inside their lives, aspirations and the root causes of their problems, a process she likens to an ‘archaeological dig’.

That process of immersion generates ideas, which are tested with quick and dirty prototypes – a music group where a manager of some sheltered flats plays Frank Sinatra over the phone to lonely but music-loving Stan and other residents. Then tweak and scale up, using the prototype to try and raise the necessary funding.

So how does this compare to the kind of stuff I read every week on innovation in aid and development? The approach has echoes of Adaptive Management and participatory methods, but Cottam is a lot more concerned with the emotional world – loneliness, dependency, relationships, kindness – a serious gap in a lot of the thinking and practice on development.

Considering this is a book about rebuilding individual and community agency, the state still plays a huge and central role in Cottam’s world. No other institutions (faith groups, sports, arts organizations) seem to exist in these communities, which seems odd, given her emphasis on relationships and social capital. As well as humanising the welfare state, why not try and diversify the relationships and networks that support people and communities?

The style grates at times – this is an unashamed sales pitch for a new idea. Victories are numerous and save bucket  loads of money; defeats are temporary set-backs; opponents are knaves or fools.

loads of money; defeats are temporary set-backs; opponents are knaves or fools.

She waves away concerns about whether any of these approaches can go to scale on fairly flimsy grounds.

And you won’t be surprised to hear that I found her theory of change/action a bit weak. She is good on the blockers (ideas, institutions, interests) that stop her approach spreading, but apart from praising local champions in places like Swindon and Wigan, she doesn’t seem to have any suggestions of what might bring about the changes she seeks (other than publicising her undoubted successes). The original welfare state required a World War to bring it about – what will this kind of overhaul need?

But these are minor gripes – the book is great, and has made me think differently about the challenges facing the UK. I hope it does the same for others.

And here’s her much-watched TED talk on the issue

The post Book Review: Radical Help, by Hilary Cottam appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers