Duncan Green's Blog, page 76

January 29, 2019

New improved Make Change Happen: free online course for activists goes live in March

Course – keep up) on ‘Making Change Happen’. A lot of time because there were so many comments (from about 3,000 participants) and they were so interesting. Now the MOOC is coming round for its second outing, starting on 4th March, so if you missed it last time (or signed up and then flaked, like so many would-be MOOCistas) you’ve got another chance. Added bonus is that we’ve made lots of improvements based on feedback and glitches in the first round. Sign up here.

Here’s the blurb:

‘Make Change Happen is a free online course which provides changemakers and activists with an understanding of how change happens and key skills for influencing change. The course provides an engaging dynamic online space where learners can share ideas and learn from each other as well as from the core teaching material, videos and case studies. The course was developed by a cross-confederation team at Oxfam with the support of Open University and is hosted on the Futurelearn platform.

Make Change Happen reopens on March 4th and is open until May. Learners can register and join the course at any point during that time. The course is self-paced with 8 weeks of lessons, including on context analysis, power and systems, collective action, spheres of influence, messaging and narratives, and overcoming challenges.

Campaigners, activists, community organisers, civil society partners, and programme managers with an influencing objective will find this course especially valuable for their professional and personal development.’

Campaigners, activists, community organisers, civil society partners, and programme managers with an influencing objective will find this course especially valuable for their professional and personal development.’

If you’re interested in MOOCs in general, or whether to sign up for this one, it’s worth taking a look at the summary report of the first run. Lots of positive feedback (I’ll spare you the soundbites and endorsements, but they’re pretty good) and some interesting findings:

A reasonable geographical spread – Europe (2318); Asia (843) and Africa (521) were the best represented continents – where was the Americas? Like they don’t need a bit of help on activism right now?……

Very even spread of age ranges between 25 and 55, with a solid 9% of participants in the over 65 bracket. Go grey panthers!

Just over 2/3 (69%) of participants self identified as female (compared to 29% as male) – is that typical for MOOCs?

What struck me most was the emotional depth and intelligence of the conversation, both in the materials and the lovely interaction between participants, often thousands of miles apart. I have to own up here, I sometimes underestimate the emotional side of activism, but issues of self care, support and kindness emerged both as central to the practice of making change happen, and as some of the best qualities in the MOOC.

I’d be interested in feedback from any FP2P readers who took part.

The post New improved Make Change Happen: free online course for activists goes live in March appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

January 28, 2019

Please help me answer some scary smart student questions on Power and Systems

Tomorrow night I am doing an ‘ask me anything’ session on skype with some students from Guelph University in Canada, who have been reading How Change Happens. They have sent an advance list of questions, which are really sharp. I’d appreciate your views on 3 in particular:

Are there important differences to note between processes of long-term change and temporary victories of social movements? How can we tell which one we are witnessing?

How can we tell if something is a short scandal or a true critical juncture?

How would you say we could determine if a movement is successful?

All 3 are basically about the difficulty of ‘navigating through the fog’ of complex systems that are characterized by uncertainty, ambiguity and unpredictability. Everything looks beautifully clear in hindsight – we can now say that Gandhi picking up salt from the sea shore was an act of genius. But could we have said so when he was planning it, or at the time? Was it only effective because of the over-reaction of the British?

uncertainty, ambiguity and unpredictability. Everything looks beautifully clear in hindsight – we can now say that Gandhi picking up salt from the sea shore was an act of genius. But could we have said so when he was planning it, or at the time? Was it only effective because of the over-reaction of the British?

I could do some hand waving about how a good power analysis can help you place your bets better, understand how a short term victory can be translated into legislative or institutional change. Which in turn raises the importance of insider-outsider alliances – social movement victories, if they are on policies or legislation, need to be translated into practice by insiders.

But part of me also thinks this is a fool’s errand. All you can do is use your best judgement, and learn as much about the system as you can, but in the end the fog only clears in hindsight and that’s just how life is. Anyone got a more satisfactory answer?

As for the last question, success is in the eyes of the narrator – when a big social or political change happens, there are usually multiple possible explanations, all overlapping, and which becomes the accepted version is down to who writes the history. Activists often credit other activists with victories, and downplay the role of other players and luck. For example, many diplomatic breakthroughs in recent years have come in the wake of terrorist attacks – The Doha Development round as a response to 9/11; the Gleneagles agreement on aid, debt and climate change in  response to the London bombings that happened in the middle of the summit; the Paris Climate Change agreement, which happened just weeks after the horrendous shootings in Paris. Yet the narratives around those events often give the credit to leaders and/or campaigners.

response to the London bombings that happened in the middle of the summit; the Paris Climate Change agreement, which happened just weeks after the horrendous shootings in Paris. Yet the narratives around those events often give the credit to leaders and/or campaigners.

And here’s the full list of questions, in case you want to add further advice – like I said, really sharp:

Systems thinking and social change in complex systems:

Can you give examples about practical ways activists (and non-activists for that matter) can apply complex systems thinking in every day strategies and activities?

Why is it important for activists to adopt systems thinking when looking at states and elaborating their strategies?

Are there important differences to note between processes of long-term change and temporary victories of social movements? How can we tell which one we are witnessing?

Is fundamental change (e.g. a real shift in our approach to environmental protection) possible in today’s political system?

How can we tell if something is a short scandal or a true critical juncture?

One of the videos we watched suggested that the three core requisites for social change are: engaged individuals, organizational infrastructure, and critical junctures (political opportunity). Would you agree with this view?

Why is it important for activists to learn how to “dance with systems”?

Social movements, citizen activism, and leadership

How would you say we could determine if a movement is successful?

Do you think that all successful social movements must be non-violent?

Are, on average, movements led by a charismatic figure more likely to succeed than those with a horizontal structure?

Do you think mass social movements need to attract high-profile allies or can the mases be enough by themselves?

If you were to come up with your own definition of power – what would you say the primary source of power is?

What is the biggest mistake activists make in their power-mapping exercises? What is the most useful approach to power-mapping exercises?

Do you find that social media is overall helping youth movements or is it a distraction?

What is the most pressing issue social movements should be addressing today in your opinion?

Over to you.

The post Please help me answer some scary smart student questions on Power and Systems appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

January 27, 2019

Links I Liked

‘Yo get these guys off a subway & onto broadway cuz this is lit’ Qasim Rashid

Feminist solutions to man-made economic inequality

Good news on the Ebola vaccine from Congo: “the evidence the WHO has been gathering in North Kivu — where nearly 64,000 doses have been administered — point to the vaccine being ‘highly, highly efficacious.'” ht Atul Gawande

These five Oxfam innovations are changing the way people fight poverty. Really interesting mix – not all ICT, but nothing on power, norms, governance etc. Can we have a second collection on that?

Alan Hudson of Global Integrity is sharing his 1000-strong library of articles on adaptive development, open government, systems, complexity and learning. If you’d like access to Alan’s Evernote collection please drop him a line at alan.hudson@globalintegrity.org with your email address

Mexico’s largest airline is having some fun with Americans. Ht Kevin Sieff

Check out the combo of throat singing, deep lyrics, and amazing instruments and landscapes The Hu (really?) is a Mongolian heavy metal band whose youtube videos have racked up over 10 million views. Music from 1 minute in. Backgrounder on the band here. Ht Chris Blattman.

The post Links I Liked appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

January 25, 2019

Summary of FP2P posts, week beginning 21st January (8m)

The post Summary of FP2P posts, week beginning 21st January (8m) appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

January 24, 2019

What have we learned about Empowerment and Accountability in fragile/violent places?

programme, studying how E&A function in fragile, conflict and violence-affected settings (FCVAS) – a more exact category than ‘Fragile/Conflict States’, which recognizes that it’s not always whole countries that are fragile/violent. This week we had a brainstorm to try and distil the overall narrative from the growing pile of research, primarily from Pakistan, Myanmar, Mozambique, Nigeria and Egypt (here’s a full list of publications so far – A4EA Publications 2016-2018). Here are my entirely selective highlights (A4EA colleagues, feel free to add your own).

Working in FCVAS means thinking about emotions and their impact on activism. In particular, fear – what is the legacy of past atrocities, or the impact of current threats on people’s interest in changing their situation? What are the different kinds of fear and what impact do they have on the likelihood and nature of social and political action? How are trust and social cohesion destroyed and rebuilt? How does agency emerge, or, as A4EA researcher Katia Taela put it, based on her work in Mozambique: ‘how do people come to the point of sitting and deliberating on possible courses of action? We still know very little about how that happens.’

Bring Back Our Girls march

These feel like huge blind spots in a sector still based primarily on assumptions that giving people access to information and channels for action should be enough for them to step up. Instead action emerges from swirling clouds of emotions and relationships – fear, love, rage, trust, hope and resignation, all of them off/below the developmental radar.

You can see these as a kind of ‘enabling environment’ for action –the emotional and normative ecosystem that must be in place before action is likely. For both scholars and practitioners, that means getting new disciplines into the room – psychologists for a start; it also means deepening the growing interest in norm shifts and how to bring them about.

This got me harking back to the paper on donor theories of change that I wrote at the start of A4EA. One of the findings of that paper was:

‘Today, donor thinking on E&A in FCVAS is at something of a crossroads. One current of thinking advocates deeper engagement with context, involving greater analytical skills, and regular analysis of the evolving political, social and economic system; working with non-state actors, sub-national state tiers and informal power; the importance of critical junctures heightening the need for fast feedback and response mechanisms. But the analysis also engenders a good deal of scepticism and caution about the potential for success, so an alternative opinion argues for pulling back to a limited focus on the ‘enabling environment’, principally through transparency and access to information’

At the time, I felt very divided on this – my heart was with the first group, hence all the stuff on this blog about

E&A meets hip hop – Mozambique

thinking and working politically, doing development differently etc etc. But my head was with the second, even though in practice it was advocating a rather laissez faire, hands off approach; and I’m a sceptic on the value of transparency unless loads of other stuff happens.

This week’s conversation pointed to a more exciting alternative – a more ambitious approach to the enabling environment, that targets the emotional and normative pre-conditions for action. So instead of concentrating on changing particular laws and policies, how do we build the enabling conditions for more action to emerge, driven by local people and communities? How do we help them overcome fear, change norms on the value of action, build leadership and confidence? That sounds like an agenda worth pursuing.

A second thought-provoking discussion was where to look for success. The programme thus far has looked at a few well-known past success stories, but when it has tried to follow current events and social movements, success has proven hard to spot. Most activism doesn’t get very far in these settings, it seems.

That surely makes a case for a bit of positive deviance – how do we trawl current events more systematically to find those social movements that are getting somewhere, and see what we can learn from them? We identified at least four ways of doing this:

Networks – aka researchers, practitioners and activists swapping notes on interesting stories they have come across

Ethnography, or its cheaper cousin, Governance Diaries, which can spot micro-levels of action as they emerge in particular communities

Big data: as more and more people go online, can we trawl social media for spikes in the use of words like ‘meeting’ ‘protest’ or ‘I’ve had enough’?

Crowd Sourcing: how about running the activist equivalent of Facebook’s 10 Year Challenge. Paint a picture of your community ten years ago and now, and then see what patterns emerge?

Approaches based on the enabling environment or positive deviance both pose major challenges to business as usual for aid donors and organizations. Predicting and measuring results are much harder, as is proving impact. But the emerging findings of the research suggest we should at least be taking these ideas seriously, if we really want to support empowerment and accountability in messy places.

The post What have we learned about Empowerment and Accountability in fragile/violent places? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

January 23, 2019

I testified at the trial of one of Joseph Kony’s commanders. Here’s what the court didn’t understand.

Originally published in The Monkey Cage at The Washington Post on 17th January

Otim (a pseudonym) is a former child soldier of the Lord’s Resistance Army, the Ugandan rebel movement led by Joseph Kony. On the battlefield, Otim believed spirits rendered him bulletproof. They spoke to him in dreams and allowed him to see the future, albeit a limited one with no hope of escape. When the bullets finally hit Otim, he could see only one explanation: He had disobeyed Kony’s spirits.

Kony’s command over his soldiers extends into the realm of metaphysics: He claims to be possessed by a range of spirits. Spirit possession has a long history in Northern Uganda, but Kony’s soldiers believe him to be possessed by particularly powerful spirits, allowing him to predict the future, heal the sick and read minds — qualities that intimidate many combatants like Otim, who were abducted at young ages.

In my research on the LRA, I have interacted with Otim for several years. His experiences may help us understand the story of another LRA soldier abducted as a child: Dominic Ongwen, who is now on trial for 70 counts of crimes against humanity and war crimes at the International Criminal Court (ICC). Kidnapped at the age of 9, Ongwen rose through the ranks of the LRA to become a senior commander. Much media attention has been given to the question of the responsibility of child soldiers: Should a former child soldier be held responsible for his actions after experiencing unspeakable trauma? Much less attention has been given to another striking issue of the trial, the role of spiritual elements: Is the ICC able to judge or understand the impact of the spiritual beliefs within the LRA?

Joseph Kony, leader of the Lord’s Resistance Army, speaks during a meeting in 2006. (AP)

Spiritual actions and their impacts have taken centre stage in the trial, more particularly in the duress argument that is put forward by Ongwen’s defense attorney. Ongwen, the defense argues, had no choice but to follow Kony’s orders. He was abducted and indoctrinated as a child. As an adult, he was under continuous threat. Those caught escaping were killed, and those who managed to escape risked their families being killed.

And this is also where the spirits come in: Kony’s use of the spirits, the defence argues, allowed him to control Ongwen’s mind.

This is not an outlandish argument. Research shows that many LRA soldiers never even contemplated escape because the spirits could reveal their secret hope to Kony. During the trial, a variety of witnesses have been called to testify about the spirits and their effects.

But to what extent is the ICC equipped to judge a defendant like Ongwen, for whom metaphysical experiences are key to motivations and actions?

Having worked on this issue for more than a decade, I was called as an expert witness to testify about these spiritual elements in the LRA. I was not alone: In previous months, a number of Ugandan witnesses were called in to discuss spiritual issues, including former rebels and a traditional healer, called an “ajwaka.”

The prosecutors didn’t bother to cross-examine any of the Ugandan witnesses on this subject. Although they and I described similar phenomena, the prosecution chose to effectively ignore their messages and cross-examine me — suggesting a Western scholar posed more of a threat to their case than did Ugandans with direct experience of spirit possession.

This highlights a central challenge for international criminal trials. They have a limited ability to fully and fairly

No Spirits Allowed

consider non-Western norms of belief and behavior. Research shows that international criminal tribunals have “proved deaf to an enormously important system of local magical belief” and are drawing on “an unrealistic Western norm,” according to anthropologist Tim Kelsall.

Moreover, researchers know that participants at trial — whether victims’ representatives, witnesses or prosecutors — draw from their own disciplinary and cultural tool kits, with very different ideas about what constitutes knowledge and how to authenticate it.

This also became clear in the Ongwen trial. While questioning me, the prosecutor referred to the courtroom as a “forensic” setting and appealed to “the laws of science,” as well as the “laws of biology, chemistry, physics” to establish the objective truth. Yet research on religion, magic and warfare uses a different method. Instead of probing for “factual truth,” it is concerned with the meanings and functions of these metaphysical manifestations and these beliefs’ impact on behaviour — and is less interested in establishing causality and apportioning responsibility. A legal approach, by contrast, seeks clear patterns of causality between isolated variables and focuses on the “objective” way in which this knowledge was achieved.

In other words, and linking back to Otim’s example from above, a “forensic” approach would check whether Otim was actually bulletproof because of the spirits; the other approach would want to understand the impact of Otim’s spiritual belief on his behaviour.

By juxtaposing the role of spirits with the “laws of biology, chemistry, physics,” the prosecution lawyer indeed suggests that metaphysical phenomena cannot be considered in a courtroom. This tells us two more things. First, the ICC is culturally quite distant from these phenomena. In her book “Fact-Finding Without Facts,” law professor Nancy Combs shows how cultural and linguistic influences affect the ways facts are transmitted and understood in international criminal trials. By declining to cross-examine Ugandan witnesses about spirits, the prosecutor suggested their reality was too distant and not relevant enough to merit inquiry.

Dominic Ongwen, from a US State Department ‘wanted’ ad

Second, this also shows the difficulty in framing belief in spirits and the impact on behaviour into applicable legal categories of international criminal law. Kelsall’s previous research for the Sierra Leone Special Court has shown the divide between the legal worldview, on the one hand, and on the other, the people they are trying and the victims they claim to represent. In other words, people’s belief in spirits and how that affects their behavior is not sufficiently reflected in the court’s ruling.

Further, indigenous voices on these practices are considered difficult or impossible to fit into legal categories, while outsiders — such as Western scholars — are accepted as translators into legal settings. This adds to the distance between these trials and indigenous knowledge.

In sum, the Ongwen trial shows how international justice is fraught with difficulties. While international law claims to apply universal justice, it is underequipped to deal with integral parts of the worldview of many of the people it tries and relies on for testimony. It remains to be seen how willing and able the ICC will be to take spiritual beliefs into account in its rulings.

The post I testified at the trial of one of Joseph Kony’s commanders. Here’s what the court didn’t understand. appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

January 22, 2019

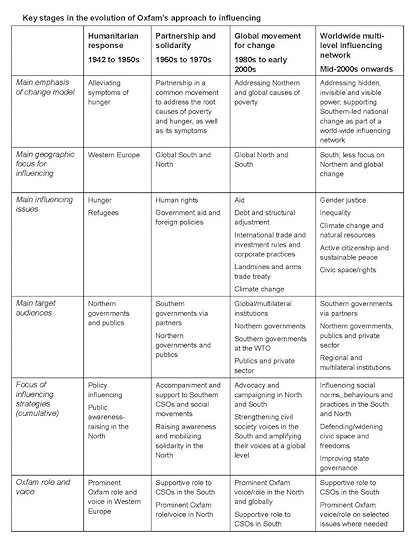

How has Oxfam’s approach to Influencing evolved over the last 75 years? New paper

Oxfam ‘Greek Week’, 1943

Oxfam has just published a reflection on how its approach to ‘influencing’ has evolved since its foundation in 1942. Written by Ruth Mayne, Chris Stalker, Andrew Wells-Dang and Rodrigo Barahona, it’s stuffed full of enlightening case studies and should be of interest to anyone who wants to understand how INGOs developed their current interest in advocacy, lobbying, campaigns etc. Some extracts from the exec sum:

‘The paper defines influencing as ‘systematic efforts to change power relationships; attitudes, social norms and behaviours; the formulation and implementation of official policies, laws and regulations; budgets; and company policies and practices in ways that promote more just and sustainable societies without poverty’.

Influencing has been part of Oxfam’s change model from its foundation in 1942. But, as Table 1 illustrates, its approach to influencing has evolved over time.

Future Directions

INGOs are facing a series of challenges that have been described as an existential threat. Externally these include shifting global power relations, the fragmentation of civil society groups around myriad single issues and changing funding landscapes. Internally their integrity as change agents is challenged by institutional demands such as growth, funders’ priorities, brand visibility, and reporting. They are also criticised for being cumbersome, slow, and – like most large institutions – unable to ‘white-water raft’ through turbulent times. There are currently three main proposals for how INGOs might respond to such challenges:

Stay big and grow as the only way to remain relevant, and provide a counterbalance to the powerful vested interests of market concentration by big business, and to global elites;

Become more agile by downsizing, going local and supporting spin-offs in order to support partners and develop, test and spread local solutions;

Act as a hub to facilitate global networks that build power from below and link local, national, regional and global efforts as part of a global movement for change – an approach currently being pursued by much of the Oxfam confederation.

Size, agility and networks all matter greatly to organizations’ futures. But care is also needed not to inadvertently jettison INGOs’ established strengths. For example, Oxfam’s history of tackling the structural causes of poverty has generated a set of influencing competences that are as important as ever. These include: its global reach and relationships; its ability to catalyze international solidarity; its holistic multi-level and multi-pronged influencing capacities and strategies; and its ability to make visible the human impacts of macro policies, among others.

Davos Week 2019

Such competences remain essential, but the rise of chauvinism and authoritarian populism also highlights the urgent need for new approaches and strategies. INGOs could help build a powerful constituency for change in both the South and North, while still being consistent with their missions, if they could:

Coalesce around a positive shared vision and narrative aimed at creating a fairer, more inclusive and sustainable world. This will require much closer and longer term collaboration with and between both domestic and international movements and with development, human rights, labour, single issue, identity and environment groups, than has been seen so far.

Jointly prioritize and assign a proportion of institutional resources to collectively address with allies the key structural causes of current system challenges – such as power and gender imbalances, corporate (lack of) regulation, or the capture of governments by elites. This will require greater use of multi-level, multi-pronged influencing strategies to tackle visible, invisible and hidden power;

Broaden communications and public engagement strategies to engage a much wider section of society, rather than mainly focussing on existing active supporters. This would mean complementing the traditional focus on the poorest and most vulnerable, with strategies that address the anxieties and wants of wider sections of society affected by precarious employment, stagnant wages, the withdrawal of essential services and environmental destruction, South and North;

Balance critiques with increased effort and investment to identify, model, promote and communicate solutions that can benefit wider sections of society. I/NGOs will need to stand ready to hook solutions to windows of opportunities as they emerge;

Increase efforts to cultivate long-term active citizenship and organizations in the North as well as the South, rather than simply mobilizing people to support pre-defined branded campaigns. Doing so effectively will need a combination of new creative online and offline (face-to-face) participatory methods and support for training and mentoring;

Increase understanding of, and support for, grass roots associations, women’s rights organizations and social movements (while taking care not to impose agendas or inadvertently co-opt them);

Spend more time directly and actively listening to, learning from and finding common ground and shared solutions with a more diverse range of individuals and organizations;

Continue to strengthen the legitimacy, accountability and the internal cultures and practices of NGOs and CSOs, as important goals in their own right, and also to ensure the social mandate to operate. The stakes could not be higher. If I/NGOs can learn from past success and failure to strengthen their influencing strategies, they can help to channel the current wave of public disenchantment towards humane, just and sustainable solutions; if they don’t, others will inevitably do so in more regressive and chauvinist directions.’

The post How has Oxfam’s approach to Influencing evolved over the last 75 years? New paper appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

January 21, 2019

Twenty five years more life: the real prize for tackling inequality

services like health and education

Imagine having 25 years more life. Imagine what you could do. Twenty-five years more to spend with your children, your grandchildren. In pursuing your hopes and dreams.

In Sao Paulo, Brazil, a person from the richest neighbourhood will on average live 25 years more than a person from one of the poorest areas. In Nepal, a child from a poor family is three times less likely to reach their fifth birthday than a child from a rich family. In Kenya, where I live, a girl from a rich family is 73 times more likely to continue her education beyond secondary school that a girl from a poor one.

Inequality between rich and poor is not primarily about having a bigger house or a faster car. It is about the impact on the things that really matter in life, and nothing matters more than how long you get to live.

The relationship between public services and economic and gender inequality is the core topic of our Davos paper this year. How inequality translates into brutally unfair health and education outcomes, and conversely the power public services can have in reducing the gap between rich and poor and between women and men.

We make particular use of the fantastic data available for most developing countries because of Demographic and Health Surveys, which disaggregate by wealth quintile.

One of our findings is the huge variation between countries. As this graph shows, in Thailand and Rwanda, pregnant women from poor backgrounds can expect almost the same level of care as those from rich backgrounds, but the gap is enormous in countries like Ghana or Indonesia. Thailand is an amazing success story, delivering comprehensive universal public healthcare despite a per capita income the same as that in the U.S. in 1930.

One of our findings is the huge variation between countries. As this graph shows, in Thailand and Rwanda, pregnant women from poor backgrounds can expect almost the same level of care as those from rich backgrounds, but the gap is enormous in countries like Ghana or Indonesia. Thailand is an amazing success story, delivering comprehensive universal public healthcare despite a per capita income the same as that in the U.S. in 1930.

The report opens with a foreword from Nellie Kumambala, a Malawian secondary school teacher, who I have known for 20 years. She is wonderful, and one of the many female public sector heroes showcased in the report.

All too often the World Bank and others seem to more consistently focus on lazy, absentee and ignorant public sector workers. I have long thought that this was deeply unfair, and the heroic job being done by most teachers, doctors and nurses around the world each day against huge odds should be shouted from the rooftops.

As the majority of the world’s teachers, doctors and nurses are women, denigrating them is sexist too. The report this year really seeks to go further than previous years in integrating a strong analysis of gender and economic inequality, and has a great section on unpaid care, and the role that public services can play in redistributing the billions of hours of unpaid work done by women each day.

The other barnstorming foreword in the report is from Nick Hanhauer, a billionaire who more than any other has spoken out against the dangers of extreme inequality, and the need for billionaires to pay more tax: ‘I have absolutely no doubt that the richest in our society can and should pay a lot more tax to help build a more equal society and prosperous economy…It is not a question of whether we can afford to do this. Rather, we cannot afford not to.’

He is not alone in calling for us to revisit the taxation of wealth. Our report opens with our usual analysis and killer facts on the mega-rich. The number and wealth of the world’s billionaires has almost doubled since the financial crisis, and last year was increasing by $2.5 billion a day. Meanwhile the World Bank has highlighted that the pace of reduction of extreme poverty (those living on less than $1.90 a day) has halved, and the number is rising in Africa.

One of my favourite facts this year is that just 1% of Jeff Bezos’ fortune is the equivalent of the whole health budget in Ethiopia. He is currently the richest man in the world, the first in history to have a fortune of over $100 billion. He recently gave an interview where he said he has decided to spend his fortune on space travel, as he can’t think of anything else to spend his money on. I am sure you would have several suggestions. We certainly do.

In the paper we join with the IMF, the Economist Magazine, Bill Gates and others in pointing out that wealth is structurally undertaxed, and there is a very strong case for increasing wealth taxes. Tax rates on the richest are the lowest they have been in decades in many countries. In developing countries the average top rate of personal income tax is just 28% and the top rate of corporate tax just 25%. Only 4 cents in every dollar of tax income comes from taxes on wealth. We calculate that if the richest 1% in each country paid an additional 0.5% of tax on their wealth, it would raise more money than it would cost to educate all the 262 million children out of school and provide healthcare that would save over three million lives.

In the paper we join with the IMF, the Economist Magazine, Bill Gates and others in pointing out that wealth is structurally undertaxed, and there is a very strong case for increasing wealth taxes. Tax rates on the richest are the lowest they have been in decades in many countries. In developing countries the average top rate of personal income tax is just 28% and the top rate of corporate tax just 25%. Only 4 cents in every dollar of tax income comes from taxes on wealth. We calculate that if the richest 1% in each country paid an additional 0.5% of tax on their wealth, it would raise more money than it would cost to educate all the 262 million children out of school and provide healthcare that would save over three million lives.

The Davos paper this year marks the first in a number looking at the power of universal public services in creating a more human economy, and how they can lead the fight against inequality. Your bank balance should never dictate how much your children learn or how long you live.

The post Twenty five years more life: the real prize for tackling inequality appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

January 20, 2019

Davos is here again, so it’s time for Oxfam’s new report – here’s what it says

First of two posts to mark the start of Davos. Tomorrow Max Lawson digs into the links between inequality and public services.

How do you follow a series of Killer Facts that have really got people’s attention? Every year the world’s political and economic leaders  gather in Davos, and in recent years, Oxfam has done its best to persuade them, and their press entourage, to focus on the way that growing inequality is holding back global poverty reduction.

gather in Davos, and in recent years, Oxfam has done its best to persuade them, and their press entourage, to focus on the way that growing inequality is holding back global poverty reduction.

This kicked off in 2014 with ‘85 richest people as wealthy as poorest half of the world’. Since then, we’ve updated it every year. It’s become almost ritualized: we publish our report, get a conversation going with the media and decision makers, and then sundry critics try and scramble aboard the bandwagon by rubbishing our numbers, only to be swatted down by our in-house geeks.

Davos kicks off this week (albeit without Donald Trump). This year’s report, Public Good or Private Wealth?, has the by now familiar ‘killer facts’ – the world’s 26 richest people now own the same wealth as the poorest half of the world – down from 43 in 2017; the 3.8 billion people who make up the poorest half of the world saw their wealth decline by 11 per cent last year while billionaires’ fortunes rose 12 per cent.

But this report feels different, more ambitious in some respects: It pulls together a number of zeitgeisty influences – Piketty + #Metoo + popular exasperation with tax dodgers, all with a strong social media vibe. The Exec Sum is now an infographic (see below). It pays more attention to framing, going beyond the standard NGO report format,  once memorably described to me as ‘Bad Shit; Facty, Facty’. It highlights success stories to show what is possible, and tries to develop a more joined up narrative – something like a manifesto for a feminist global welfare system to deliver the SDGs, captured in its 3 over-arching recommendations:

once memorably described to me as ‘Bad Shit; Facty, Facty’. It highlights success stories to show what is possible, and tries to develop a more joined up narrative – something like a manifesto for a feminist global welfare system to deliver the SDGs, captured in its 3 over-arching recommendations:

‘Deliver universal free health care, education and other public services that also work for women and girls. Stop supporting privatization of public services. Provide pensions, child benefits and other social protection for all. Design all services to ensure they also deliver for women and girls.

Free up women’s time by easing the millions of unpaid hours they spend every day caring for their families and homes. Let those who do this essential work have a say in budget decisions and make freeing up women’s time a key objective of government spending. Invest in public services including water, electricity and childcare that reduce the time needed to do this unpaid work. Design all public services in a way that works for those with little time to spare.

End the under-taxation of rich individuals and corporations. Tax wealth and capital at fairer levels. Stop the race to the bottom on personal income and corporate taxes. Eliminate tax avoidance and evasion by corporates and the super-rich. Agree a new set of

global rules and institutions to fundamentally redesign the tax system to make it fair, with developing countries having an equal seat at the table.’

global rules and institutions to fundamentally redesign the tax system to make it fair, with developing countries having an equal seat at the table.’The full report is 71 pages + notes, and feels more like a compendium of background materials and research findings that other organizations and activists can mine for their own work. It is backed up by a pretty funky website.

It will be fascinating to see how it works, and whether the media is turned off by a fuller narrative, instead of an isolated killer fact. Fingers crossed, because I think the content is really good. And important. A lovely quote from Wangari Maathai captures its aspiration:

‘In the course of history, there comes a time when humanity is called to shift to a new level of consciousness… to reach a higher moral ground. A time when we have to shed our fear and give hope to each other. That time is now.’

And here’s the Info Exec Sum:

The post Davos is here again, so it’s time for Oxfam’s new report – here’s what it says appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

January 19, 2019

Audio Summary (6m) of FP2P posts, week beginning 14th January

The post Audio Summary (6m) of FP2P posts, week beginning 14th January appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers