Duncan Green's Blog, page 72

April 2, 2019

The ‘Black Market’ of Knowledge Production

Arthur Owor

David Mwambari

Researchers David Mwambari and Arthur Owor question the effect of money in producing knowledge in post-conflict contexts and argue that it restricts independent local research. These insights were developed at a recent workshop at Ghent University, which brought together Ghent-based researchers and a group of researchers, commonly called “research assistants”, from post-conflict and developing regions.

In order to support more informed decisions about development aid and humanitarian aid in conflict and post-conflict societies, academics, policy makers, and journalists travel to these communities to collect

knowledge. To gather knowledge, they will almost always rely on local people to facilitate their research: a driver, a translator, security personnel, a fixer, a research assistant, sometimes all rolled into one. One of our colleagues from DRC recounts his experience working as a local researcher here.

What separates the foreign “expert” from the local expert is, in part, money. In order to facilitate swift access to information, the foreign researcher spends money into the research environment, thus creating a peculiar market for knowledge production. Local researchers, working in their own right, lack such resources and cannot compete. Instead of acting as independent researchers, they must then accept the subordinate role of research assistant. The way that interviewees and local researchers are compensated provides a window onto the hierarchies of value in knowledge production.

Paying the interviewees

Copyright: 401kcalculator.org

The ethics of compensation to those being interviewed are unclear. Should participants and interviewees be paid for their time? In Uganda, due to high numbers of research projects implemented in one area often requiring the same respondents, the local research council has introduced a requirement to compensate respondents for their time.

A senior researcher from Belgium criticised this practice as ‘buying’ research, but local researchers all agreed that interviewees should at least be reimbursed for their transportation costs. The assumption here is that participating in research is voluntary and that people who have suffered often want to tell their stories. Since the policy maker, the journalist and the academic are compensated in different ways (albeit in their diverse fields of interest) for reproducing and retelling these stories, why shouldn’t the owner of the story benefit from her/his own story? But this can also have unintended consequences: the amounts offered by foreign researchers have set an unsustainable precedent that has virtually shut out independent local researchers.

Paying the local researchers

The industry of knowledge production is rarely regulated in conflict or post-conflict contexts. Local or national governments are fragile or non-existent and therefore aid agencies, humanitarian organizations, local non-governmental organizations, individual academics or consultants regulate the payment to the service providers. If rules do exist, researchers rarely adhere to them beyond filling out bureaucratic forms. The person with the money, usually the outside senior researcher, not only sets the standards and determines what questions are asked but also determines how money will be used, who is paid for what, and how much they receive.

In a study conducted in Northern Uganda, a colleague called the result a “black market of knowledge production”. In a workshop at Ghent University researchers from Belgium, Rwanda, Germany, United Kingdom and invited researchers from Kazakhstan, Philippines, Uganda, Peru, Bangladesh, Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Rwanda, some pressing questions were raised.

The first was from a Rwandan participant who asked: “Who should regulate and determine how different service providers should be paid?” International experts in most cases are paid by aid agencies, they are put up in good hotels, and often have contracts that secure their jobs. As the colleague from Bangladesh mentioned, their assistants rarely have any paperwork or even a reference letter to show that they took part in producing this information, let alone a project title to put on their CV.

Another participant from the Philippines, the head of a local organization, explained that the motives to collaborate with foreign researchers go beyond monetary rewards. They prefer that the researcher carry out specialized tasks, such as training members of the community-based organizations in specific skills. Others prefer that the researcher donate an amount of their choice to the organization, or help in advocacy campaigns that are ongoing during their visit.

Copyright: Shutterstock.

Who keeps track?

There are also huge gaps in law and regulations regarding knowledge generation from both the country of the researcher and the host country. In some cases these experts will sometimes only follow ethical rules from their funding or home institutions rather than respecting local regulations on research. Such laws, for example relating to data storage and sharing, have become bones of contention.

Knowledge produced in the ‘black market’ is also prone to imposters ready or take advantage of the naïve Western researcher for their research grants. In these fragile and poor contexts, they pretend to be research assistants but lack the necessary research skills. They often end up producing questionable reports. This is often more evident in journalism because it is available to the public, but the same thing also happens away from the limelight in academia and policy reports.

While one can neither generalize about entire regions with many countries and hundreds of cultures, Africans and Europeans do seem to understand the use of money differently. A dissatisfied research assistant from an African context may not complain about their pay to the Western researcher, who then leaves feeling that he/she reimbursed the person adequately, or even better than other local jobs. When one pushes to negotiate, a European researcher might feel as if they are being taken advantage of, and suspect they are being overcharged.

Money is seen in some circles as a corruptor of vital relations necessary in processes of knowledge production. In other contexts, it may be seen as a leveller of expectations of respondents and knowledge brokers. Either way, the myths, awkwardness and discomfort around money in the knowledge production ‘black market’ need to be unpacked, discussed openly and demystified.

The post The ‘Black Market’ of Knowledge Production appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

April 1, 2019

We’re changing up FP2P: here’s the plan (but we haven’t got a name yet – please help!)

In the 11 years since I launched this blog, it’s churned out getting on for 2 million words across 2,500+ posts, generating 12,600 comments (thanks everyone). It’s time to change things up.

Time to decolonise Duncan?…

Up to now, I’ve been running the blog as pretty much a solo effort – roughly a day and a half a week to generate 5 posts, deal with comments, and read lots of guest blogs from people keen to share their ideas on FP2P. Right now I have 8 potential posts in the queue. The trouble is that most of them are from my demographic: northern, white, working in high-profile spaces (although pretty well balanced on gender).

These are the voices that largely continue to frame global debates and skew discussions.

Which means FP2P readers are missing out on other views and voices, and we want to fix that. We want to include more ideas and content from thinkers, researchers and doers in the Global South, in a wider range of formats (video, podcasts, forums and debates etc). We want to spotlight unheard (at least in the North) voices and amplify stories that are often ignored. Essentially, we want to start rebalancing some of the asymmetries that continue to characterise a large chunk of development communications, and start making these conversations more horizontal (easy job, right?).

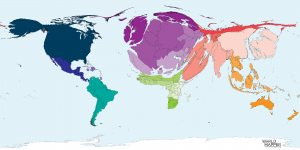

World map of IMF votes..and of main authors.

Copyright: Worldmapper.

But it’s not just about what gets posted here, or whether we need to expand our list of authors. We want this project to be a part of a broader effort to challenge our assumptions, ask hard questions, and strengthen efforts to tackle the blind spots in conversations about local and global development. Because we know development itself as a concept and practice is deeply embedded in power relationships, involving issues of representation and the way we produce knowledge. So if we want to better understand the depth of issues, we can’t really afford to exclude the perspectives of those actually affected by them.

There will be more discussions on this in later posts, with more details on the blind spots we will be trying to identify and challenge. For now, here’s some exciting news.

María Faciolince

Thanks to a bit of funding from Ford and Hewlett Foundations, we have recruited a person (half time) to begin sourcing content outside of the northern bubble, and to help me run the blog. She is María Faciolince (left), a whip smart Colombian-Antillean woman, with a degree in Anthropology and Psychology, a Masters in Anthropology and Development, and an activist with lots of experience generating multimedia content.

Here’s our plan: for the next 3 months, we’re going to try lots of new stuff, and then take stock on what works, what doesn’t. That will include:

Stories of endogenous change that may not have external/aid element to them

Links to breaking stories, like what to read on Yemen, Syria, Venezuela, etc. from authors in those countries.

Reposting top commentary from Southern thinkers, or reviews of their books.

Turning the tables, including commentary on Northern events from Southern perspectives

Measurement: Poverty? Power? What counts? Including debates around indicators and methodology.

New Issues: What’s coming up the development agenda? And what isn’t but ought to be?

But we’re open to other suggestions too – the whackier the better.

I’m very excited but also a bit anxious – I’m guessing that being decolonised may involve rethinking many things, and learning to ‘hand over the stick’ more often.

But FP2P is not going away – I’ll still be posting several times a week, along the lines that have interested enough readers in the past to generate good traffic and great commentary. My ugly mug will still be on the homepage. We’re still committed to avoiding the worst excesses of devspeak, to wallowing in real life ambiguity and confusion, and to sticking to the central core theme of the move from poverty to power. We just want to try some new, cool stuff out, and then we’ll ask you what you think.

And the first job is to choose a name for the project – Global Voices was taken, Southern Voices sounds too ….. Northern. I can only come up with naff ones like ‘New Voices’, ‘Changing the Record’ or ‘FP2P, but we really mean it this time’. ‘Decolonising Duncan’ is obscure and insufficiently serious. So please help us out with some suggestions, (no Boaty McBoatfaces please), then we’ll pick the best ones, and have a vote…..

The post appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

March 30, 2019

Audio Summary (8m) of FP2P posts, week beginning 25th March

The post Audio Summary (8m) of FP2P posts, week beginning 25th March appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

March 29, 2019

Don’t get the hump, but what really changed on global income, and what didn’t?

I was wondering when that phrase would appear….. Andy Sumner & Kathleen Craig of the  King’s Department of International Development continue the humpology debate.

King’s Department of International Development continue the humpology debate.

Duncan’s blog on the global hump and Jose Manuel Roche’s reply raise the question of what has actually changed and what hasn’t. Here’s (yet) another take and in an attempt to be less geeky and more narrative-based, no graphs, we promise.

First, what has actually changed?

There is a new hump which is an emerging polarisation within the developing world between ‘stuck’ and ‘moving’ countries

Most developing countries have grown over the last two decades. Only a small set of 25 developing countries remain ‘stuck’ in terms of economic growth. These countries are home to about 10% of the population of the developing world. In contrast, most of those living in the developing world are resident in faster-moving countries. This multi-speed world generates a binary between a group of countries that are likely to remain ‘stuck’ in terms of growth, and a larger set of developing countries that have been growing substantially (and where most of the world’s poor live). Yet it is important to remember that the income gap between the majority of the ‘moving’ developing countries and the developed world remains enormous (more on that in a moment).

There has been a dramatic decline in the significance of aid

There are only about 30 developing countries that remain highly aid dependent and these countries are home also to about 10% of the population of developing countries. There’s some overlap with the moving/stuck polarisation but not completely. In short, in most developing countries, ‘traditional’ official development assistance (ODA) is, or in the foreseeable future will become, insignificant compared to domestic resources.

There are dramatically expanding domestic resources to end poverty, but those resources are kind of ‘locked’

One hump or two?

Around three-quarters of the world’s poor live in countries with the potential to end poverty through national redistribution, i.e. through changes in domestic public expenditure and taxes. However, this is only the case up to approximately the US$5-per-day poverty line, which is still pretty low (any FP2P readers offering to live on that? Thought not). Above that, international redistribution remains necessary to eradicate poverty. Further, many developing countries – like any country – will face political contestation to introducing new taxes, reducing subsidies that benefit the rich most like petrol subsidies or curtailing military expenditure, in favour of redistributive transfers to the poor. In short, resources are kind of locked and national political economy constraints will still make ending poverty difficult.

Second, what has not changed or not changed so much?

There is a ‘sunshine narrative’ on catch up, yes, though it fades without China

Yes, economic growth is taking place across the developing world, but the ‘sunshine’ narrative of falling inequality between developing and developed countries has been oversold, because it largely depends on China. The fall in between-country inequality is very modest between 1990 and 2015 if China is removed from consideration.

And even China still has a long way to go in terms of catching up with the richer countries, in that China’s GDP per capita (2011 PPP) stands at $15,000, which is still only around a quarter of the GDP per capita of the US. China could theoretically catch up by the mid-2030s if it has another two decades of fast growth. Yet the most sophisticated long-run projections err on the side of caution, forecasting that China will catch the US around 2050. India could also catch up with the GDP per capita of the US but it would need another 5 decades of fast growth. And Brazil and South Africa, which start out on a much higher per capita income than India, may not catch up at all. Of course, this is all largely speculative. It does, however, demonstrate the assumptions that are needed to trumpet a catch-up argument.

Global monetary poverty has fallen, but every 10 cents on the poverty line adds another 100 million people and multidimensional poverty doubles the total poverty count

Global poverty has fallen at the new extreme poverty line of $1.90-per-day, but the fall in the global poverty

or maybe four?

headcount when China is excluded is more modest. This is not at all to say that the income growth among the poorest people in the world has not been positive. The issue is that setting very low poverty lines and communicating trends based on these lines may evoke a story that absolute poverty is virtually eradicated or on the road to being eradicated in a decade or so.

Yet the estimate that a tenth of the world population is poor by the $1.90 poverty line sits alongside the fact that every 10 cents added to that line adds almost 100 million people to the global poverty headcount, up until around the $3.50-per-day mark. Additionally, poverty measured as multidimensional poverty – including education, health and nutrition poverty – is double that of the $1.90 income poverty count.

And if a poverty line is used that is associated with a permanent escape from poverty – $10-per-day – some 4.5 billion people (well over half the people on the planet) are still living in poverty.

So all things considered, some important stuff has changed. There are fewer very poor countries (as Duncan noted), a fall in the significance of traditional aid, though that should just mean the beginning of a new era not the end of one as countries wind down traditional aid, concessionary finance is still important, and especially so if expanding domestic resources are ‘locked’ by domestic political economy.

On the other hand, catch up is a long way off for most developing countries. And small changes in the poverty line add many more people to the global poverty headcount. So, in some ways how much has really changed? And for those going through cold turkey, here’s the graphs.

That enough on humps (for now)? Hope so, because FP2P has a big new announcement coming up next week…..

The post Don’t get the hump, but what really changed on global income, and what didn’t? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

March 28, 2019

Doing the hard stuff in tough places: please help us find the ‘seemingly impossible’ stories of success

The list of reasons to feel depressed is long and growing. Recent elections ushering in sexist and violent heads of states; climate change even worse than predicted; backlash to #MeToo and, if you’re in the UK, the political swamp known as ‘Brexit’. Depressing – and urgent. When it comes to climate change, it’s now or never. Gender oppression? Time’s up. Economic inequality? We’ll never end poverty without reducing those ever-widening gaps.

For inspiration, we can draw on the amazing stuff happening in all parts of the globe. Female genital mutilation (FGM) levels are plummeting, off-grid renewable energy systems have seen energy poverty levels nosedive in Afghanistan and Nepal, and £300 millions of public revenues have been recouped in Nigeria through forensic audits in the petroleum sector. We need many more such examples that show how to tackle systemic causes of injustice and poverty. We can stretch our sense of the possible by learning from recent examples, hidden gems that may not have been shared or documented widely.

So thinking about success at scale, which top three examples of development – with or without external ‘aid’ – would you nominate? What inspiring efforts have you been part of, worked with or know about? We will be looking across a couple of dozen examples to inspire, challenge and inform Oxfam’s future work. We’ll ask if we need to update our understanding of poverty, how rapid change at scale takes place, and the role of influencing efforts or practical support in driving such change.

So thinking about success at scale, which top three examples of development – with or without external ‘aid’ – would you nominate? What inspiring efforts have you been part of, worked with or know about? We will be looking across a couple of dozen examples to inspire, challenge and inform Oxfam’s future work. We’ll ask if we need to update our understanding of poverty, how rapid change at scale takes place, and the role of influencing efforts or practical support in driving such change.

We’re looking for examples that reduce poverty at scale by tackling (1) economic inequalities; (2) climate change and resource depletion; or (3) gender injustices. Or a mix. Each example should have information on:

its contribution to rapid poverty reduction at scale, improving the lives of tens of thousands of people or more

the positive impact has emerged within the last 10 years

be located in a challenging context – fragile governance, conflict affected; restricted civic freedoms; in places with very low income and human development indicators; or a mix.

Examples involving Oxfam and partners include the Raise Her Voice campaign in Pakistan that trained women leaders in 30 districts and drove advocacy efforts for the introduction of a Domestic Violence Bill in Sindh Province, as well as the Africa Climate Change Resilience Alliance in Uganda that supported the Ugandan government to produce seasonal forecasts in 35 local languages for smallholder farmers nationwide. Examples further from home include the proliferation of more equitable business structures and relationships with workers in the food supply chain; changing social norms around childhood marriage in West Africa; and international fossil fuel divestment campaigns.

Examples can come from evaluations, case studies, news articles and even blogs. But any example has to have been taken successfully to scale. ‘Going to scale’ is pretty tough to define –different routes, contexts and scales. But we’re thinking of efforts that have accelerated and multiplied small impacts, possibly leading to policy change, substantially increased the population served or broadening the scope of impact. We’re also interested to hear about  how you understand scale.

how you understand scale.

As Walt Disney said: ‘It’s kind of fun to do the impossible’. We’d just love to hear more about it. We’ll share what we find – selecting the best of the best for blogs. But first, we’re all ears (see right).

You can tell us in the comments section (with your email contact, please), or email us at gracelynhigdon@gmail.com or rmayne1@oxfam.org.uk

The post Doing the hard stuff in tough places: please help us find the ‘seemingly impossible’ stories of success appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

March 27, 2019

Where is being faith based an asset in aid & development; where is it a liability?

Christians and Muslims, discussing faith and development. Last week it was a panel organized by Tearfund, a Christian aid and development agency, to discuss a big internal review of its evolution over the 50 years since its foundation in 1968.

The conversations at the launch were fascinating – an ecosystem of faith based organizations, with far more in common with each other than with the secular aid world of logframes and targets. Islamic Relief and CAFOD planning a joint peace building exercise in Northern Nigeria; Muslims and Protestants borrowing from each other’s toolkits and faith based approaches. Everyone comfortable with notions of the divine and the sacred. It reminded me of that look of baffled pity I receive sometimes when I leave Europe and tell people I don’t have a faith – in much of the world, that is incomprehensible and sad.

SOUTH AFRICA/CAPE TOWN – 350 climate change protest march outside parlament, 24 October 2009

But back to the paper, which is great, but for the moment, an internal document (if you want a copy, contact publications@tearfund.org). The author, Dena Freeman identifies two periods in Tearfund’s history: For the first 25 years, evangelism largely ran in parallel, but separate to development work. Projects were pretty much along the same lines as the secular aid agencies, while faith was principally a motivator of staff and supporters.

From the early 90s, things got more interesting. Tearfund decided to try and devise a ‘faith-based approach (FBA) to development’. It turned out to be a difficult but important exercise, which is still going on.

Dena argues that an FBA makes some areas of work more effective, and others harder. Broadly, it can turbocharge work where attitudes and behaviours need to change. On more technical/material aspects (eg infrastructure, tools and seeds) not so much.

Which got me very excited, because many of the emerging issues that I talk about on this blog are precisely in that field of norms, attitudes, behaviours, psychology etc. Turns out that faith organizations got their first, and could have much to teach the rest of us. Some examples:

Leadership: Faith organizations often support and work through local leaders; everyone acknowledges the importance of preachers and visionaries. Big contrast to the discomfort in more secular aid agencies, which prefer to talk of class struggle (on the left), utility maximising individuals (on the right), or just obsess about tangible metrics and targets (everyone). How do you measure vision and leadership?

Localization: Faith organizations are everywhere, on the ground, legitimate, trusted. It is an almost universal research finding that the institutions trusted most by poor communities are first, their deity, and second, their faith leaders. Unsurprisingly, therefore, faith based agencies work through local partners as a matter of course, but in its FBA period, Tearfund has stepped this up with a Church and Community Mobilisation (CCM) programme, which has developed new faith-based methodologies to work with local congregations in poor countries to carry out specific faith-based programming with or for the community. It has got some amazing results. Top quote from one of the speakers: ‘Since coming to the Christian faith, I have discovered the unbelievable assets on the ground.’

Norms: Where to start? Faith organizations understand the central role of norms, beliefs, values. They are one of

Interfaith manel. Gender equity not always a strong point….

the principal shapers of those values. As aid organizations increasingly come to realize the importance of myth, narrative, and values, where better to look for advice?

The long term: no-one thinks long term like the faith organizations – ask the Vatican. If the aid sector is serious about long-term, generational shifts rather than nice, neat but ultimately inadequate 3 year project cycles, the faith groups have much to teach us – one example: the importance of early years’ education in shaping the values of future generations.

Fund-raising: a common feature of all faith organizations is that they are really good at raising money. I did my standard ‘fundraisers without borders’ pitch, and the reaction was enthusiastic. Faith organizations are already helping local communities tap into local funds, but they could do much, much more – and they seem interested in doing something about it.

Winning over the conservatives: Tearfund is operating almost entirely outside the echo chamber of Guardian readers. Many of their supporters have conservative views on sensitive issues like women’s rights. Ditto Islamic Relief. As one Tearfund staffer recalled of her first attempt to work with churches on HIV/AIDS ‘they were all about sin and damnation. It was a tough gig’, and yet by working through church structures and theology, she was able to achieve remarkable changes of heart among church leaders. Post Trump, post Brexit, faith organizations can build crucial bridges for social/attitudinal change.

What about the downsides? I think there are two. In her remarks at the seminar, Dena Freeman identified how much more problematic and potentially disastrous it is to adopt these kinds of approaches in communities of mixed faiths, or where the aid agency’s faith group is in a minority. There, inter-faith dialogue can be a big help, but marching in with other aspects of a faith-based approach can backfire badly.

The other downside is more fundamental, and I’m still chewing it over. All the above takes a purely instrumental approach to religion – being faith-based means you can get more impact, better results in a range of fairly conventional activities. But what about the more intrinsic aspects of faith? After all, Amartya Sen’s definition of development as the ‘freedoms to be and to do’ must surely include the freedom to believe in the God of your choice. So is belief itself a sign of development?

And following that down the rabbit-hole, are some faiths more ‘developmental’ than others? If conversion from one religion to another results in previously downtrodden groups experiencing an upsurge in ‘power within’ and starting to demand their rights, whether on issues of caste, sexuality or gender, is the act of conversion itself developmental?

Lots to chew on. And just to be crystal clear, these are my comments, not an expression of the views of Tearfund.

The post Where is being faith based an asset in aid & development; where is it a liability? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

March 26, 2019

How a new land rights study amplifies women’s hopes and fears – and makes us think again about solutions for everyone

A couple of weeks ago, writing on this blog, Duncan asked a question: How do we, in the international development community, recognize and work with (let alone measure) issues like love, shame, fear, solidarity?

As an advocate for women’s land rights, this question resonated with me. Whenever I hear from women about the fragility of those rights and their efforts to strengthen them – as I’ve done across 16 countries and two continents – these facets of the human condition are ever present.

Fear and hope – attitudes to the future – matter because they determine how we behave. They might inform decisions about investment in land, and about families: decisions that can shape lives, communities and economies.

As for measuring these qualities, I might have the beginnings of an answer, found in a report released this week by Prindex, a new international survey which asks men and women how they feel about the security of their rights to stay in their home and continue to work their land. It’s a joint initiative of the Overseas Development Institute and Global Land Alliance.

Prindex found that 1 in 4 people fear losing their homes or other land. That’s remarkable in itself.

What’s more, Prindex found that women were, on average, over 12 percentage points more likely than men to express fear for their right to retain their home in the event of divorce or the death of their spouse. This is a land rights gender deficit.

What’s more, Prindex found that women were, on average, over 12 percentage points more likely than men to express fear for their right to retain their home in the event of divorce or the death of their spouse. This is a land rights gender deficit.

That matters for women, and for their societies.

It is so often women who remove rocks from land, plant, fertilize, weed, and harvest crops, care for children, care for the elderly, cook, clean, carry water and wood, and all the rest without earning any money.

Women are less likely to invest sweat equity in land that does not belong to them and over which they have no ultimate control. For example, one study found an increase in investment in soil quality when women’s land rights are more secure.

If their contribution is not valued in a divorce, they are likely to receive much less than their husband, who is usually the traditional money earner.

This affects many more women than those who actually divorce. It includes women that are toughing it out. How many women are in abusive or harmful relationships who cannot leave because if they leave, they leave with nothing—no land and no money?

In Uganda, the Prindex survey shows that 40 percent of women are insecure about their rights to land in the case of a divorce. This tallies with one of my findings from years ago. In focus group discussions in Uganda, women openly talked about being beaten before the harvest so that they would return to their family for a while and their husbands could harvest and sell the crops before going to bring them home. In rural India, where Hindu women who divorce are regarded as a shame on their families and where women often receive nothing in a divorce, women talk about having to stay in extremely abusive situations because they have nowhere else to go.

So, where does this leave us? Prindex’s gender report shows that there is no one single solution, and that the long-term work of changing norms is key. But one finding in particular caught my eye.

Women who contemplate divorce in countries that take into account women’s non-monetary contributions to the marriage – including unpaid work on the land and caring or “reproductive” labour – when dividing property at the time of divorce tend to be less fearful than women in countries that do not count non-monetary contributions.

Comparison of tenure insecurity of women in a divorce scenario and whether the law provides for equal access to nonmonetary contributions (purple = yes; orange = no)

Countries where women display relatively low rates of tenure insecurity in divorce scenarios (30% or below) are all countries in which the division of property benefits both spouses at the time a marriage is dissolved.

There are countries such as Liberia, Mozambique and Burkina Faso in which divorce legislation is gender-equal but women anticipate more insecurity in divorce scenarios. This may reflect differences over whether women know of their legal rights, and whether their personal and social circumstances along with the de facto operation of courts allow them to enforce that right.

That’s another reason why Prindex asks – and we should all ask – about perceptions: because they may reflect the reality more than the laws as written in statute books.

Asking about fear and hope becomes a way to recognise that what appears to be a land law issue is also a family law issue and an issue of norms, courts, and citizen awareness. If we don’t ask about perceptions, and if we don’t make sure that we collect data from women as well as traditional heads of household, we risk neglecting a large part of the picture, and at least half of the population.

Renée Giovarelli is Senior Gender Advisor and Lawyer at Resource Equity and an expert on women’s land rights. Prindex is the largest international survey of men’s and women’s perceptions of their land and property rights.

The post How a new land rights study amplifies women’s hopes and fears – and makes us think again about solutions for everyone appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

March 25, 2019

Links I Liked

according to an OECD survey of 21 countries (not including the UK for some reason).

Do we really Live in a One-Hump World? More humpiness, this time from Jason Hickel

Complicating the Narratives. Excellent long read from Amanda Ripley on the need to rethink journalism

‘The goal: To build a liveable city out of a refugee camp, one that might endure even if the refugees can return home someday.’ Interesting National Geographic long read on an experiment in Uganda, taking a v different approach to S Sudan refugees ht Tobias Denskus.

Providing sanitary pads in 30 schools in Western Kenya reduces absenteeism by 5.4 percentage points. Ht Dave Evans

LSE announces Amartya Sen Chair in Inequality Studies

The dos and don’ts of influencing policy through research: a systematic review of advice to academics.

An impromptu haka by a small group of Christchurch schoolchildren in tribute to their murdered classmates, full of catharsis and anger as scores of students join in. Makes me cry ever time.

The post Links I Liked appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

March 23, 2019

Audio summary (6m) of FP2P posts for wb 18th March

The post Audio summary (6m) of FP2P posts for wb 18th March appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

March 22, 2019

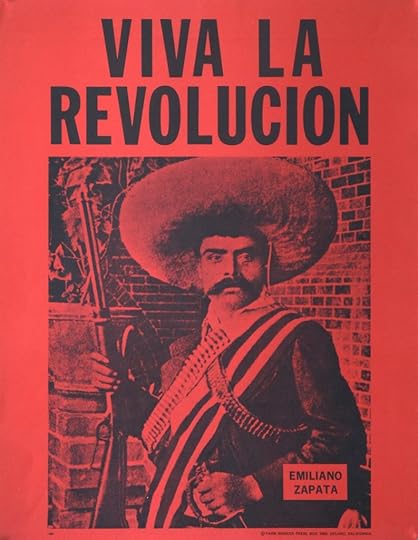

How Latin American is my Theory of Change?

A recent email exchange with Asa Cusack of the LSE’s Latin America and Caribbean Centre (plus the Latin American tone of this week’s posts – Mexican, Argentine and Venezuelan guests in one week must be some kind of record) triggered a bout of nostalgia about my early days travelling in and writing about Latin America (roughly 1979-98) and set me wondering: to what extent are the views and arguments in How Change Happens and on this blog shaped by those formative years?

The book’s core focus is on power and systems: In the early 80s, I emerged with a shiny new degree in physics and  headed for Latin America and subsequently, a life as a London-based activist and writer on human rights and social struggle in Chile and Central America. I distinctly remember the sensation that I was having to rebore my mental pathways, away from the linear, deductive logic of physics to the inductive thinking of politics – essentially exploring politics and society as a complex system, with multiple feedback loops, where knowledge and understanding were always partial at best.

headed for Latin America and subsequently, a life as a London-based activist and writer on human rights and social struggle in Chile and Central America. I distinctly remember the sensation that I was having to rebore my mental pathways, away from the linear, deductive logic of physics to the inductive thinking of politics – essentially exploring politics and society as a complex system, with multiple feedback loops, where knowledge and understanding were always partial at best.

I also remember being intrigued by the way Central American politicians and guerrilla leaders (this was the height of the region’s armed struggles) talked about ‘political space’ as something almost tangible, endlessly contracting and expanding. It felt like they could ‘feel’ the space – an acute observation and understanding of it determined what you could/couldn’t do, and getting it wrong could be (literally) fatal. When I now talk about understanding ‘power’ as the invisible force field of social change, I often think back to those conversations about space.

As for the book’s focus on Active Citizenship – well, that is quintessentially Latin American. My time in Central America gave me both an interest in armed struggle, and in the social movements that underpinned it – especially the base Christian Communities, where catechists in El Salvador would conduct Freirian discussions aimed at ‘conscientización’, using The Exodus as the core text. More on the role of faith as a driver of change next week.

But at some point in the early 90s, as an editor and writer at the Latin America Bureau, I became influenced by both books and individuals working on a very different region – the ‘Asian Tigers’ of South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Hong Kong and more recently, Malaysia and Indonesia. These brought home to me the role of effective states and industrial policy and the painful contrast with the economic failings of import substitution in Latin America. My focus on activism became a duopoly – an exploration of the interaction between ‘active citizens and effective states’ became the basis for my first big non-Latin American book (From Poverty to Power, 2008).

I summed up the change in the introduction to my PhD thesis, written back in 2010, which was actually a PhD by Published Work, including a ‘critical review’ of my previous work (v therapeutic – see here for details):

‘Looking back over the two decades covered by these works, it is possible to discern a clear, but unfinished trajectory in the evolution of my thinking. Faces of Latin America (1991) opens in a continent of embattled popular movements, fighting against elite-controlled governments and an essentially regressive economic system. Heroic defeats are to be expected, albeit punctuated by the occasional often pyrrhic victory. The implicit assumption in this analysis was that economics and economic structures shaped politics, rather than vice versa – structure dominates agency.

By the late 1990s, I had become more involved in trying to understand these economic structures and was beginning to read, and get excited about, the role of the state both as a deliverer of growth and as a potential independent counterweight to domination by both domestic and foreign economic elites. I had also broadened my understanding of citizenship beyond national protest movements to wider discussions of human rights.

By the late 1990s, I had become more involved in trying to understand these economic structures and was beginning to read, and get excited about, the role of the state both as a deliverer of growth and as a potential independent counterweight to domination by both domestic and foreign economic elites. I had also broadened my understanding of citizenship beyond national protest movements to wider discussions of human rights.

With my move to the development NGO sector in 1997, I began to broaden the geographical remit of my research from an almost exclusive focus on Latin America and the Caribbean, to a wider concern with the developing world.’

Full 15,000 word critical review here, for any masochists among you: Duncan Green critical review October 2010 FINAL

What is also interesting is the absence of aid from much of this – if you are a Latin Americanist, aid looks a lot less important (except in a handful of places like Haiti), than it does if you work on Africa, for example. Over decades in the aid sector, I’ve found that a reliable initial guide to the political priorities and assumptions of any new northern colleague comes from asking them where they had their formative experience in a developing country. If it’s Latin America, expect a focus on social movements, struggle and justice; if Africa, a deep scepticism of the state and political elites and strong opinions for/against aid; if East Asia, the transformatory power of economic growth. Not so sure on people who cut their teeth in South Asia – chronic poverty and social exclusion?

Guilty as charged: How Change Happens reflects my Latin America formation. If you want to see some of the books I wrote about the region in those distant times, check out Faces of Latin America, Silent Revolution or Hidden Lives. And if any potential funders want to finance a 30 year retrospective, you know where to find me…….

The post How Latin American is my Theory of Change? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers