Duncan Green's Blog, page 74

March 7, 2019

“The Socialist and the Suffragist”: A poem for International Women’s Day

Said the Socialist to the suffragist:

“My cause is greater than yours!

You only work for a special class,

We for the gain of the general mass,

Which every good ensures!”

Said the suffragist to the Socialist:

“You underrate my cause!

While women remain a subject class,

You never can move the general mass,

With your economic laws!”

Said the Socialist to the suffragist:

“You misinterpret facts!

There is no room for doubt or schism

In economic determinism—

It governs all our acts!”

Said the suffragist to the Socialist:

“You men will always find

That this old world will never move

More swiftly in its ancient groove

While women stay behind.“

”A lifted world lifts women up,”

The Socialist explained.

“You cannot lift the world at all

While half of it is kept so small,”

The suffragist maintained.

The world awoke, and tartly spoke:

“Your work is all the same:

Work together or work apart,

Work, each of you, with all your heart—

Just get into the game!”

[ht Max Lawson]

The post “The Socialist and the Suffragist”: A poem for International Women’s Day appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

March 6, 2019

What are the consequences of the shift from a two hump to a one hump world?

I’ve been using this idea in a few recent talks, and thought I’d test and improve it by bouncing it off FP2P readers. It uses a simple pair of graphs on global income distribution to start thinking through how the ‘aid and development’ sector is changing, or resisting change.

The starting point is that we have moved from a two hump to a one hump world – long since pointed out by Branko Milanovic, Max Roser, Hans Rosling et al. In 1974 the two humps shaped the global narrative on development – there is a poor hump (‘the South’) and a rich hump (‘the North’). Asia largely accounts for the South. Screengrabs from the wonderful Gapminder.

Milanovic, Max Roser, Hans Rosling et al. In 1974 the two humps shaped the global narrative on development – there is a poor hump (‘the South’) and a rich hump (‘the North’). Asia largely accounts for the South. Screengrabs from the wonderful Gapminder.

Key to graph colours

Development was about the North helping the South catch up (remember First and Third World?), whether through aid, or a fairer deal on trade and capital flows – a ‘New International Economic Order’ was proposed by the UN in 1974. That North-South thinking became a deep frame which lingers on, especially among the older cadre of aid workers and activists, Northern politicians and in the UN system.

Fast forward to 2015 and we now have a one hump world. China and much of the rest of Asia have moved up the income scale. What does this mean for aid and development?

North-South is no longer a particularly useful view of the world, (with the partial exception of sub-Saharan Africa). That’s the point brilliantly made by Hans Rosling. But what else follows from the shift? I see three trends, each of which is being resisted by the status quo ante.

North-South is no longer a particularly useful view of the world, (with the partial exception of sub-Saharan Africa). That’s the point brilliantly made by Hans Rosling. But what else follows from the shift? I see three trends, each of which is being resisted by the status quo ante.

Firstly, inequality: Instead of the nation state being the most useful unit in understanding global differences, what matters are the divides between social groups within and between countries – that is partly why inequality has shot up the agenda in recent years. The other reason is the unequal distribution of the wealth generated by the global economy over the last 30 years, memorably described by Branko Milanovic’s elephant graph (two camels and an elephant – nice). But talking about inequality is far more threatening for elites than talking about poverty, so there’s plenty of push back, or dilution of the concepts (think ‘inclusive growth’).

Second, the localization of politics: an increasingly vocal, literate and organized civil society and growing local middle classes have shifted the focus of social and political change to domestic arenas – issues like taxation, governance, welfare systems are now where they should be – primarily topics for national debate. In the aid sector, the rise of southern civil society organizations has prompted increasing pressure for aid to be channelled through them, rather than northern aid agencies, but the aid sector is proving highly resistant to reform. The same goes for academia, where tension is growing over the northern

Where’s the elephant?

domination of research and even the definition of what constitutes knowledge about development.

Third, a shift to common challenges. With the exception of a shrinking number of aid-dependent countries, many of

them with fragile or predatory states, and/or conflict affected, the rest of the world increasingly faces challenges that are either shared or collective: shared = road traffic, pollution, obesity, mental health, which are issues to be addressed in any country; collective = climate change, tax evasion etc, where solutions have to be collective, or they won’t work. For both shared and collective challenges, aid $ may not be the main issue – it’s more about joint action, exchange of ideas and experiences – i.e. a more grown up conversation between equals than the inherently unequal dialogue between donor and recipient. But much of the political and social appeal of the aid business is built on the exotic – diseases the North doesn’t have, farmers that barely exist, the poverty porn of extreme hunger. Mental health, road traffic or tobacco addiction don’t seem to work as well and struggle to get the attention they deserve.

So there’s 3 consequences of the shift to a one hump world – any others?

The post What are the consequences of the shift from a two hump to a one hump world? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

March 5, 2019

A primate brain in a human world: Evolutionary biology and social change

Inequalities Institute. This was my favourite of his posts on social change. You can find the rest of the series on the Atlantic Fellows for Social and Economic Equity blog or on Medium.com.

Shame. It might make most of us feel horrible, but it has also become a well-known part of the toolbox of modern social-change campaigning. And often with great success. In the realm of campaigns to change corporate behaviour, “shaming” those companies has become an important tactic.

While most people – based on their personal experience of shame – have a basic understanding of why “shaming” works to affect behaviour, more profound explanations for the mechanisms at work can be found by looking at our very distant past. Not only can we find explanations for why this approach works, but we can also gain insights into its limitations – and what that means for some of the defining challenges of our times, such as inequality and climate change.

To get there, we will need to take a trip down memory lane: a long, long trip, back to the days of our ancestors. We will start, however, with what has become one of the most cited scientific articles ever written. There are probably  less than a handful of people who have graduated in the field of economics and have not had to read ecologist and philosopher Garrett Hardin’s seminal paper, “The tragedy of the commons”. And for good reason. Hardin’s argument is elegant, simple and convincing, albeit not necessarily universally true.

less than a handful of people who have graduated in the field of economics and have not had to read ecologist and philosopher Garrett Hardin’s seminal paper, “The tragedy of the commons”. And for good reason. Hardin’s argument is elegant, simple and convincing, albeit not necessarily universally true.

Hardin is trying to answer the question of what will happen to a resource that is communally owned, like public lands or our atmosphere. He focuses on the English commons, land that formally belonged to the king but was available to everyone. His argument was straightforward: in such a situation, “each herdsman will try to keep as many cattle as possible”, because while overgrazing will ultimately destroy the land for everyone, that fact should not change a rational herdsman’s behaviour. The reason, according to Hardin, is simple: while all users of the commons will share the “costs” of overgrazing, the “profits” from each additional animal will be the herdsman’s.

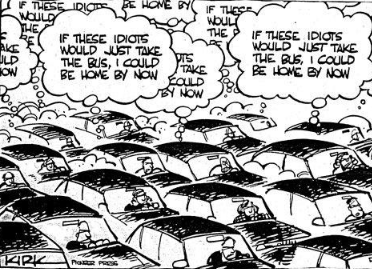

If we assume that a herdsman’s decisions are mainly motivated by their self-interest (in this case maximising profits by grazing as many of their cattle as possible), Hardin’s argument is very compelling. And if we look at some of humanity’s biggest commons – like the atmosphere or the fish in our oceans – this seems to be exactly what is happening. While everyone will share the costs – climate change – of my holiday flight to Hawaii, the benefits are all mine to enjoy. Self-interest trumps the common good and therefore ultimately risks destroying the most important commons of all.

So it seems like Hardin was right. Except he wasn’t. At least not always. While his model seems to work whenever the commons is really big, more recent research has found that in smaller commons – including his own example of the English commons – people behave very differently from what he predicted. The question is why.

So far, we have mostly looked to social sciences for answers to that question. But perhaps part of the answer is in our biology.

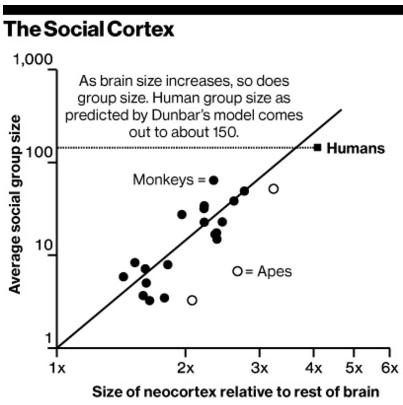

In 1992, Robin Dunbar, a specialist in primate behaviour at the University of Oxford, started to notice something interesting. Primates seemed to live in groups of a certain size. That size was different for different primate species, but similar within the same species. Smaller groups tended to grow to a certain size but once they exceeded it, group dynamics changed or broke down and the groups usually split up. While the phenomenon was easy enough to observe, nobody seemed to be able to explain what determined the size of the groups. Until Dunbar started looking at the size of different primates’ brains. What he found was very interesting: brain size was clearly correlated with group size of a specific species of primates. That correlation became known as “Dunbar’s number”. For humans, that number is around 150.

but similar within the same species. Smaller groups tended to grow to a certain size but once they exceeded it, group dynamics changed or broke down and the groups usually split up. While the phenomenon was easy enough to observe, nobody seemed to be able to explain what determined the size of the groups. Until Dunbar started looking at the size of different primates’ brains. What he found was very interesting: brain size was clearly correlated with group size of a specific species of primates. That correlation became known as “Dunbar’s number”. For humans, that number is around 150.

Why 150? While we don’t know for sure, scientists think that the reason is that for most of human history we lived in much smaller groups. In other words, our evolution prepared us for a life that is very different from that of most of us today. Only after we switched from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to agriculture-based societies did we start to live in much larger groups than our ancestors. While our lifestyles have changed dramatically since the advent of the first agricultural revolution about 12,000 years ago, our biology hardly changed at all.

Although 150 seems like a relatively small number, Dunbar has illustrated what this number actually means in terms of complexity of group relationships that we need to keep track of. If we look at an average modern family of five people, we have to keep track of 10 separate relationships: our relationships with the other four family members as well as the six other two-way relationships between the others. However, if you add your extended family – say a group of 20 people – you now have to keep track of 190 two-way relationships: 19 involving yourself as well as the 171 relationships between the other family members. I will spare you the math for a group of 150 people, but this example illustrates why understanding the social dynamics in a group of that size is no easy feat.

If Dunbar is right, and subsequent research suggests he is, we are biologically equipped to self-govern groups of up to 150 people. Interestingly, as author Malcolm Gladwell reports, when looking at “21 different hunter-gatherer societies for which we have solid historical evidence, from the Walbiri of Australia to the Tauade of New Guinea to the Ammassalik of Greenland to the Ona of Tierra del Fuego [Dunbar] found that the average number of people in their villages was 148.4”. In groups up to that size, social cohesion seems to be enough to make sure that we can live together without infighting within the group or destroying our livelihoods.

The main “enforcement mechanism” of that social cohesion seems to be shame. In groups up to that size, people’s personal relationships with their peers are strong enough that the emotion of shame serves as a powerful deterrent to prevent members from acting against the group’s best interest.

The main “enforcement mechanism” of that social cohesion seems to be shame. In groups up to that size, people’s personal relationships with their peers are strong enough that the emotion of shame serves as a powerful deterrent to prevent members from acting against the group’s best interest.

Most of us, of course, live in groups that far exceed that number. And most of the time we manage to do that without all hell breaking loose. We are able to do that because we have created formal structures to enable us to manage relationships with much bigger groups of people than we (pre-)historically had. Those structures serve us well in many circumstances. But they fail us in others, namely in those cases where we are facing problems that exceed our formal governance structures. Problems such as climate change or global inequality. Problems in which the actions of one group have consequences for another, but in which shaming doesn’t work because of the size of the group, and in which formal structures don’t work because they don’t exist.

This has been an intractable problem for a long time, with no obvious solution in sight. The global structures set up to deal with such problems have had limited success. On the issue of climate, they are delivering too little, too late. On the problem of global inequality, most indicators are pointing in the wrong direction. Despite those issues, most problems of this scale still require a global solution. At the same time, it is worth exploring whether there are other ways that can help solve today’s problems.

Prehistorical tragedy of the commons problems were often solved (or avoided) by the first shame campaigns in history. Maybe today we need to reinvent the tradition of shame campaigns, adjusted to work for much bigger commons. One way of doing so would be to take a closer look at peer groups. New research by Robin Dunbar has found that even in the age of Facebook, “the size and range of online egocentric social networks, indexed as the number of Facebook friends, is similar to that of offline face-to-face networks”. Of course we know many more people, but the size of group of people who are close enough to really have an influence on us seems to not have changed.

This suggests that the same mechanisms are still at work, and it might be worth thinking about ways of using them better. Rather than just looking at how power is distributed in the formal power structures we are used to, be they in government or in business, we ought to spend more time looking at the informal structures surrounding those in power. Identifying the informal peer groups, the groups where shame works as a governance mechanism, might allow us to translate the big commons problems we currently struggle to solve into small commons problems that we are biologically better equipped to deal with.

Sebastian Bock is an Atlantic Fellow for Social and Economic Equity in the International Inequalities Institute at the London School of Economics (LSE) and a Senior Strategist at Greenpeace International . You can follow him on Twitter @sebastianbock

The post A primate brain in a human world: Evolutionary biology and social change appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

February 18, 2019

Off on hols, back in two weeks!

February 17, 2019

Why a new report on UK aid reform is contradictory, evidence free and full of holes

debates have shifted from ‘how much?’ to ‘how should we spend it?’ A new report calls for a seemingly radical shake up of how UK aid should be spent. Oxfam’s Gideon Rabinowitz explains what’s at stake, and why simplistic solutions are not all they seem.

The latest salvo in the debate about the future of UK aid was fired last week by a report, co-authored by Bob Seeley (Conservative MP) and backed by Boris Johnson (former UK Foreign Secretary, and Conservative MP), which called for a significant shake-up of UK aid spending.

The Report – “Global Britain: A 21st Century Vision” – published by the Henry Jackson Society (HJS), calls for the UK Department for International Development (DfID) to be re-integrated into the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), for UK aid to increasingly promote UK strategic interests and for the UK to apply its own definition of Official Development Assistance (ODA), breaking with the rules applied by the OECD for more than half a century.

In common with similar recent interventions on this agenda, the Report does not explicitly call for dropping the 0.7% aid target (although one could view its proposals to fundamentally change the definition of aid as an effort to do just this). This suggests that the battle lines on UK aid are moving from a debate about how much we spend on aid to questions about these resources are used globally.

Generally, this Report displays some major contradictions, a paucity of evidence to support some its of its major claims and proposals, some significant blind spots and a self-defeating approach to reforming UK aid policy.

Nevertheless, it’s part of a valuable conversation about how we shape a vision for Britain’s place in the world’. It calls for Britain to continue to play a leading global role post-Brexit. It makes a passionate case for Britain to take a values driven approach to foreign policy – include promoting “Freedom from Oppression” and “Freedom of Thought”. It also robustly champions the global rules based system.

So, why am I ultimately unconvinced by the HJS’ analysis and proposals?

Contradictory visions for Global Britain

A number of the Report’s central proposals contradict its vision for Global Britain.

In calling for a watering down of the development focus of UK aid (an inevitable outcome of reorienting UK aid towards better addressing Britain’s interests), it undermines efforts to address basic human needs, reduce poverty and empower the poor and marginalised, which are surely a key element of the goals to secure freedom from oppression and freedom of thought.

Also, in calling for a break with the OECD’s (largely flexible and well governed) rules on ODA, it undermines an important element of the rules-based global system that it seeks to so vigorously defend.

Should that read ’19th Century’?

Where is the evidence?

Then there are a number of notable sweeping statements made with little or no evidence to back them up.

Perhaps most significantly, there is the conclusion that the move to “establish DfID as a separate department in the late 1990s was an error”, a statement made without reference to evidence and ignoring DfID’s significant successes and its status as one of the premier global development agencies.

There is also the statement that the OECD’s ODA rules only allow for aid to be used for economic cooperation and there is significant UK spending unreasonably excluded from ODA figures. However, in reality cultural and political cooperation is a major element of UK ODA (the British Council’s budget is almost wholly reported as ODA) and most of the exclusions are due to departmental spending not taking place in a developing country and not being focussed in any way on development! UN peacekeeping contributions are arguably an exception and do deserve more discussion.

Significant blind spots

For a Report that claims to be setting a 21st century vision it fails to address a number of important issues.

There is one very general reference to climate change, which surely has to be one of humanities greatest challenges during this century and should have been kept in mind when discussing the the role of the UK in the world in the coming decades’

There is also an unwillingness to in any way recognise and respond to the challenges of those left behind by current economic models and global inequality. The defence of the current economic model and free trade is unequivocal. However, the evidence and consensus is growing that these systems and policies need adapting to spread their benefits.

Self-defeating approach to aid

The proposal to re-absorb DfID into the UK Foreign Office and re-orient UK aid spending towards better addressing UK strategic interests is self-defeating for a number of reasons.

Firstly, such an approach could easily undermine public support for aid, given that the UK public overwhelmingly want aid to be spent on the poorest people.

Secondly, watering down the brand of DfID, a global development leader, could undermine the UK’s ‘soft power’ – the moral authority and leadership it can exert elsewhere in the international system because of its reputation on aid .

.

Thirdly, this step could undermine the effectiveness and value for money of UK aid. DfID is a global leader on issues such as aid transparency and the FCO a laggard (a point well made by Huw Merriman MP – see tweet), and there is research suggesting that independent and/or specialised development agencies promote high quality aid.

Finally, weakening the development focus of UK aid undermines its ability to support countries to find their own solutions to development challenges over the long-term, which is surely not in the UK’s national interest.

The key question addressed by this Report – how the UK should deepen its engagement in a changing world post-Brexit – is one that needs more air time, so that we can limit the risks of Britain’s global ambitions waning at this critical juncture in its history.

But this report does not deliver that; the theme requires much more open, evidence-based and comprehensive treatment, and an honest acknowledgement of what is at stake and at risk in a radical shake-up of UK aid spending.

The post Why a new report on UK aid reform is contradictory, evidence free and full of holes appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

February 16, 2019

Audio Summary (6m) of FP2P posts, week beginning 11th Feb

The post Audio Summary (6m) of FP2P posts, week beginning 11th Feb appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

February 14, 2019

5 Things that will Frustrate the Heck out of you when studying International Development

Here’s MSc Development Management student Stella Yoh.

International Development is our passion – that’s why we’re all here. It’s what keeps us going through these late nights and grey London days.

But let’s face it, it’s not always a fun ride. As fulfilling as it is, studying International Development can be a real struggle, and if you haven’t had an existential crisis by now, you sure as hell have one coming your way.

Here are the five biggest frustrations that International Development students feel at least once during their studies.

Everything depends on context.

Sometimes you wonder if the main purpose of a top-notch education is learning how to say “it depends” with class (i.e. academic rigor). Almost every literature you read by almost every renowned academic will talk about how context specific everything is. You will rarely find anything that lays things out in a simple manner, and even more rarely, with a clear solution. If you ever find a good, simple answer, it will most likely be wrong (think KONY 2012). This can be really frustrating to us students, who supposedly came to school to get answers. Instead, we somehow end up getting even more confused?

I think we can all relate to this

The Chicken or the Egg? No one knows.

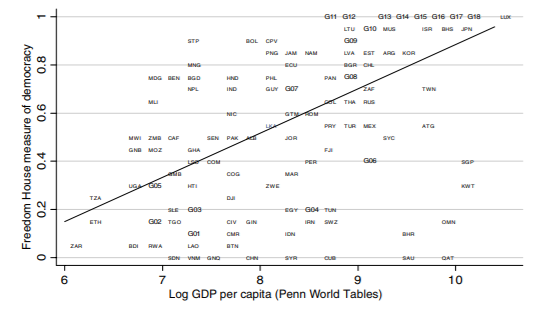

Some people really believe in the power of institutions. Others think growth depends solely on what you’re born with. We all agree that all the “good” things (democracy, well-functioning markets and state, etc.) are strongly correlated with economic growth. We’ve all seen at least one of the numerous classic 45° scatterplots, (below):

GDP & Democracy (see original: https://economics.mit.edu/files/5677)

GDP & education (original: http://hanushek.stanford.edu/sites/de... Lecture.<“THE scatterplot” of international development>

But what comes first? The good thing or the economy? Does one good thing cause another, or the other way around? Are governments corrupt because they are poor? Or are they poor because they are corrupt? Here’s an answer: it depends.

Wear all hats, or else (but choose the hat wisely).

International Development is a highly interdisciplinary area of study. You can’t possibly focus just on economics, or anthropology, or political science, because all of them are closely intertwined. The good side of this is that you will get a wide perspective and learn from the best practices of each field. But this also means that you’ll face a massive identity crisis, because eventually, you’ll have to choose your main research discipline. And although all methodologies are truly valuable, some hats are more mainstream than others (i.e. get you more funding and/or job opportunities).

Learn to wear all hats, but choose your main hat wisely.

Pessimism vs. me: does it even matter?

Have you ever met an idealist senior development professional? I certainly haven’t.

The more we learn about development, the more we have to battle with encroaching cynicism. The development industry is nowhere near perfect, and there is the repeated theme of disillusioned practitioners going back to the private sector (or for some, to academia). Many others stick it out, but are well aware of their limitations.

Understandably, tackling multifaceted, deeply-rooted problems in development can be very difficult, and even some of the world’s best minds are fatalistic. Studying (or practicing) development thus requires an extraordinary peace of mind where constant cynicism is balanced out by constant optimism, like Gramsci in his prison days: pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.

Welcome to the Real World.

You wrote a distinction paper on climate change, but this really cool job on corporate responsibility wants someone with 8+ years of experience. Sound familiar?

Once we survive the intellectual frustrations of the classroom, we are immediately slapped in the face by the job market. Most entry points to development organizations are highly competitive internships with little to no pay; and most decent full-time roles look for previous experience in investment banking or management consulting (or equivalent). Almost every talk and guide (like this one) recommends

Zen Riddle for Millenials – original: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jFzUb...

getting private sector experience in leading firms. But weren’t these giant corporations the bad guys? Now you’re telling us to go work for them?

This ginormous gap between what we learn and what we can actually do in real life, is by far the biggest frustration us students can have (the LSE careers blog can be a good resource, by the way).

You’ve good grades and a heart with passion, so why won’t they hire you? Welcome to the real world, mate.

Surprisingly enough, the point of this article isn’t actually to dishearten you. These are real frustrations that you will at some point in time feel when studying International Development. And despite these difficulties, most of you will end up working in development, in one way or another.

Because despite everything, you love it anyway.

Because this world, as imperfect it is, needs more people like you and I, who genuinely care about the problems and the solutions we come up with, however imperfect. And whatever we end up becoming in the future, be it investment banker or head of an NGO, we would be able to use our learnings and hopefully begin to work together to make things better, one step at a time.

So congratulations development students. We have a long journey ahead of us.

The post 5 Things that will Frustrate the Heck out of you when studying International Development appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

February 13, 2019

Closing Civic Space: Trends, Drivers and what Donors can do about it

International Center for Not-for-Profit Law. Nothing life-changing, but a clear and concise summary of the origins of the problem and possible responses, based on some 50 contributions to a consultation by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida). Some highlights:

‘The graph shows the legal initiatives, proposed or enacted, that restrict the freedoms of association or assembly: (1) 47% restrict the formation, registration, or operation of CSOs; (2) 28% constrain the ability of CSOs to receive international funding; and (3) 25% restrict peaceful assembly.’

‘What New Trends are we Witnessing?

Digital restrictions: Indonesia, Pakistan and Tanzania, for example – have adopted cybercrime laws and other regulations that provide largely unfettered power to monitor and surveil electronic communications.

Transparency-linked restrictions: (1) burdensome requirements for reporting and for disclosure of private information (e.g., in Bulgaria, Panama, Uganda); (2) mandatory disclosure of private assets of CSO directors and/or officers (e.g., in Ukraine and India); (3) limiting public advocacy by categorizing CSOs as lobbyists or political activists (e.g., in the United Kingdom and Ireland); (4) disclosure of private and international funders (e.g., in Hungary and Mexico); and (5) disproportionate penal provisions linked to non-compliance with reporting and disclosure requirements (e.g., in Egypt and Russia).

Denying access to CSOs in multilateral fora: CSOs and human rights defenders are subject to increasing threats, intimidation, and reprisals when they try to speak out in multilateral fora

Denying access to CSOs in multilateral fora: CSOs and human rights defenders are subject to increasing threats, intimidation, and reprisals when they try to speak out in multilateral foraDiscrediting CSO voices in multilateral fora: government-organized NGOs (GONGOs) participate in multilateral fora like the UN Human Rights Council. GONGOs defend countries’ policies, attempt to delegitimize genuine civil society voices, and consume time, space, and other limited resources.

Impeding freedom of movement: preventing civil society representatives from traveling abroad

Narrowing the space for INGOs: eg via restrictions on spending, mission or registration.

Stigmatizing donors: For example, the Government of Hungary has been conducting a campaign that targets the Open Society Foundation and the Central European University, as well as its founder, George Soros

What are the Origins and Drivers of Closing Civic Space?

The origins of the crackdown on civic space can be traced to the beginning of the current millennium. Throughout the 1990s, the world was in the midst of an “associational revolution,” and CSOs enjoyed a mostly positive reputation within the international community, stemming from a post-Cold War conviction that pluralistic, liberal democracies where civil society is an integral part of the social fabric are or should become the norm; as well as from CSOs’ important contributions to health, education, culture, economic development, and a host of other publicly beneficial objectives. Reflecting this, in September 2000, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Millennium Declaration. Among other provisions, the Declaration emphasized the importance of human rights and the value of “non-governmental organizations and civil society, in general.”

This changed after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. As President Bush launched the “War on Terror,” discourse shifted away from human rights and the positive contributions of civil society, and CSOs instead became a target. “Just to show you how insidious these terrorists are,” Bush stated in his September 2001 remarks on the executive order freezing assets of terrorist and other organizations, “they oftentimes use nice-sounding, non-governmental organizations as fronts for their activities.” President Bush then launched a “Freedom Agenda” to advance democratic transitions in the Middle East, which included support for civil society as a key component, giving rise to the perception that CSOs were linked to a foreign agenda. For both reasons – the association of civil society with terrorism and the association of civil society with Bush’s Freedom Agenda – governments around the world became increasingly concerned about civil society, particularly CSOs that received international support.

In many ways, 2005 marked the beginning of the “associational counter-revolution.” Because of changes in the  geopolitical environment, the Bush Administration’s “War on Terror,” concerns over “color revolutions,” and other factors, governments felt empowered to enact legislation restricting civic space. Countries such as Russia, Zimbabwe, and Venezuela were early adopters, and over the following years, scores of countries have followed suit. Another wave of legislative constraints emerged after the so-called “Arab Awakening,” which began in late 2010.

geopolitical environment, the Bush Administration’s “War on Terror,” concerns over “color revolutions,” and other factors, governments felt empowered to enact legislation restricting civic space. Countries such as Russia, Zimbabwe, and Venezuela were early adopters, and over the following years, scores of countries have followed suit. Another wave of legislative constraints emerged after the so-called “Arab Awakening,” which began in late 2010.

The specific driver(s) of closing space restrictions will, of course, vary from country to country, as government and political leaders act from a variety of motivations. At the same time, one can identify several drivers that have fueled the global crackdown against civil society, including the following:

The dramatic growth and demonstrated power of civil society and civil society organizations during the 1990s;

The increasing priority given to counter-terrorism and national security by governments around the world;

A shift in global power relations, which has reduced the influence of western governments and traditional multilateral institutions and resulted in challenges to the liberal democratic model;

The increasing collusion between political and economic elites to protect their interests against oversight or criticism; and

The rise in ideological and religious extremism, resulting in increasingly hostile environments for defenders of vulnerable groups, including those representing women, LGBTI, minorities and others.

In recent years, a number of countries have seen a rise in intolerant political populism. These populist movements seem to portend a further narrowing of civic space, including in established democracies. This may embolden authoritarian governments to further constrain civil society. Indeed, the civic space challenge is embedded into a  much larger struggle relating to democratic recession and the emboldening of autocrats. Since we are likely on the cusp of a new wave of restrictions on civil society, the engagement of donor governments, as principled, credible voices on civic space issues, is more important than ever.

much larger struggle relating to democratic recession and the emboldening of autocrats. Since we are likely on the cusp of a new wave of restrictions on civil society, the engagement of donor governments, as principled, credible voices on civic space issues, is more important than ever.

The suggestions to donors are a bit underwhelming, unfortunately: make your support for civic space public and clear; make sure your own policies are joined up (eg counter terrorism is often used as a pretext for attacking CSOs); support civil society and build alliances with other defenders, including the private sector. Still, a really useful summary of what is a huge challenge for ‘change agents’ and their supporters in an increasing number of countries.

The post Closing Civic Space: Trends, Drivers and what Donors can do about it appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

February 12, 2019

Can watching a few videos really reduce Violence Against Women?

here), but a recent RCT on violence against women in Uganda by researchers at Columbia University got my attention. Here are some excerpts from the summary on the website of Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA).

First the summary of the summary:

‘In Uganda, IPA worked with researchers to evaluate whether videos encouraging communities to speak out about and counter violence against women (VAW) in the household could change behavior, attitudes and norms related to VAW.

In surveys conducted eight months after the intervention, the proportion of women who reported any VAW in their household over the preceding six months was substantially lower in villages where the videos were screened than in villages randomly assigned to the comparison group.

The impact appears to be driven by a reduction in the perception that those who speak out against violence will face social sanctions.’

What seems to be happening here is a shift in social norms, in the categories described by Cristina Bicchieri in Norms in the Wild (see diagnostic). Progress occurs not by changing men and women’s internal beliefs, but by  changing what they think other people in their communities consider (un)acceptable. Back to IPA for more detail:

changing what they think other people in their communities consider (un)acceptable. Back to IPA for more detail:

Context:

‘Video halls, known as bibanda, are ubiquitous in rural Uganda. They typically hold 10-50 people and are located in the center of a village or trading center. Since few households in rural Uganda own TVs, bibanda are popular places to watch movies and soccer, especially among young men.

Nationally representative opinion polls suggest that some forms of VAW are widely viewed as legitimate in Uganda. However, not all violence is condoned. While 31 percent of respondents in our study said a husband is justified in beating his wife when she disobeys him, only 2 percent would condone violence perceived as more severe than slapping. Eighty-eight percent stated that others should intervene to stop violence.

Nonetheless, almost a third of women reported in 2011 that they had experienced violence such as being punched or threatened with a knife. Communities do not seem able to prevent such violence, partly because witnesses do not speak out: just one quarter of respondents in our study said they would tell authorities if their cousin had been beaten by her husband. Only one in ten would report to police. A common justification for withholding information was fear of being branded a gossip.’

The intervention:

‘Three short anti-VAW videos were produced in collaboration with Peripheral Vision International. Ranging 4-8 minutes each, the videos depicted deadly violence by a husband towards his wife and appealed to viewers to speak out about VAW in order to prevent it from escalating.

Audiences saw the videos via film festivals held in bibanda throughout 112 rural villages. Every village in the study featured a film festival comprising six popular Hollywood films unrelated to VAW that were shown once a week over consecutive weekends from July through September 2016. In 48 randomly selected villages the three short video vignettes on VAW were inserted into the intermission of the Hollywood film. In the other 64 villages, the film festivals featured video vignettes on other social issues (teacher absenteeism or abortion-related stigma), or just the Hollywood films with no video vignettes at all. These 64 villages thus constitute a comparison group that received a “placebo” film festival unrelated to VAW.

As is typical in Uganda, the Hollywood films were narrated by a VJ who added his own commentary to the movie’s storyline. Unlike most entertainment screened in bibanda, however, the anti-VAW videos were produced in the local language (Luganda) using local actors, enabling villagers to identify with the characters in the videos.

Admission to the film festivals was free of charge to encourage the attendance of a broad-based audience, and was notably successful in attracting women (31 percent of all attendees). In total, over 10,000 adults attended 670 film screenings. [31% is pretty good as bibanda tend to be very male spaces – see video from PVI]

The research team interviewed 6,449 individuals across all villages through two waves of surveys conducted 2 and 8 months after the film festivals. Importantly, the surveys were presented as opinion polls unrelated to the video campaign. Questions measured behavior and attitudes among a random sample of the adults living in the catchment area of the video hall, irrespective of their attendance of the festival. Respondents therefore include not only those who attended the screenings, but also their neighbors, community leaders and village health workers.’

Results and Policy Lessons:

‘Impact on violent incidents: Eight months after the anti-VAW vignettes were shown, women in the treatment group were 5 percentage points less likely to indicate that a woman in their household experienced any violence over the previous six months relative to the comparison group. Around 20 percent of women respondents in the comparison group reported that there was at least one case of VAW in their household over the previous six months. The campaign thus reduced the proportion of women respondents who reported any violence in their household by approximately one quarter.

Impact on social norms and attitudes: Among men and women who watched the videos, there is little evidence the anti-VAW videos had an effect on attitudes about the legitimacy of VAW or on perceptions of whether others in the community see VAW as legitimate behavior. Nor is there statistically significant evidence in favor of an increased empathy for VAW victims or a change in their perceptions about whether initial acts of domestic violence are likely to escalate.

The most plausible causal channel for the reduction in VAW appears to be a change in the willingness of victims and bystanders to speak out about violence. Both men and women who watched the anti-VAW videos were more willing to report instances of VAW to village authorities. This effect was particularly pronounced among women: When asked whether they would report a hypothetical incident of VAW across a range of different scenarios, two months after the campaign women in the treatment group were 9 percentage points (22 percent) more likely than those in the comparison group to say they would report violence across all scenarios. Eight months after the campaign, this willingness remained higher in the treatment than the comparison by a margin of 13 percentage points (35 percent). This increased willingness to report VAW may be related to a concurrent change in the perceived social consequences of speaking out, particularly among women. Women who watched the anti-VAW videos were 11 percentage points (18 percent) less likely to believe they would face social repercussions, such as scolding for gossiping, for intervening in a VAW incident.’

Wow. Can watching a few public service ads in the interval really change people’s lives that much? I really hope so, but can’t help being sceptical given the message saturation we all experience. Maybe that saturation is less in rural Uganda, or the novelty of hearing videos in your own language cuts through the noise.

Thoughts?

The post Can watching a few videos really reduce Violence Against Women? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

February 11, 2019

List of your most disastrous campaign own goals – more please!

I’m teaching a course on activism at the LSE and one of my students, Gaia Frazao-Nery, asked me a disarmingly

Bic Pens for Women – a very silly idea

simple question – can you give us some examples of advocacy campaigns that have achieved the opposite of what they wanted? I was stumped, so threw myself on the mercy of twitter. So far, I haven’t quite got the perfect example(s), but an interesting typology of failure is emerging:

Dumb Government Messaging

‘D.A.R.E. in the States. Drugs awareness programme aimed at teens. Best way to open kids up to all of the possibilities out there. Also set up false equivalence between things like tobacco & heroin (if my parents smoke cigarettes that’s as bad as me doing coke, right?).’ [Heather Marquette]

‘A lot of anti-drug campaigns that focus on scare tactics also have negative effects’ [Rick Bartoldus]

‘Scared straight in the USA’ [Rick Bartoldus]

HIV/AIDs awareness campaigns seem to have been particularly prone to own goals:

‘HIV/AIDS campaign in Botswana in 1980s/1990s, used ABC model of Uganda but paid little attention to context. Condom promotion was equated to immorality. Public campaigns were treated with scepticism. Aids became known as the ‘radio disease’. Prevalence rates skyrocketed.’ [Ben Ramalingam]

Some anti-HIV campaigns play up the likelihood of getting HIV by so much, that people just begun to assume that getting HIV is inevitable – so they stop protecting themselves. [Rick Bartoldus].

Removing things makes people value them (You dunno what you got til it’s gone – Joni Mitchell)

‘US Republicans attempting to dismantle Obamacare in 2017 – leading to huge voter outrage (including amongst rural Republican voters) over fact that people with pre-existing conditions could be denied coverage- became major campaign topic in the midterms where republicans lost big.’ [Tom Wildman]

Bad Aid Interventions:

‘Malaria eradication campaign of 1960s and 1970s didn’t take into account evolution of resistance, based on DDT as silver bullet, led to re-emergence of malaria’ [Ben Ramalingam]

Stupid Commercials:

‘Launching a new mobile telephone network in Northern Ireland with the ‘The future is bright, the future is Orange’ [Nicholas Colloff]

Bics pens for women, a huge fail [Rince This]

(Then there’s the Fiat Nova’s bafflingly poor sales record in Latin America. (No va = ‘doesn’t work’ in Spanish)…’

Accidentally giving Oxygen to your enemy:

‘The protest against Uber by London cabbies in 2014. By giving Uber tons of free publicity, led to loads of new customers downloading it. Broader lessons there about audience targeting and salience raising?’ [Paul Skidmore]

‘The protest against Uber by London cabbies in 2014. By giving Uber tons of free publicity, led to loads of new customers downloading it. Broader lessons there about audience targeting and salience raising?’ [Paul Skidmore]

Encouraging participation and then regretting it:

Take a bow,

Bad Politics:

Advocacy by international governments and others for democracy in Rwanda – during a civil war, no less – most likely had the opposite effect, one would think.[Phil Vernon] (I think this could be extended to all the push for early elections, when that destabilizes countries recovering from conflict – Paul Collier’s work is great on this)

Stuff you agree to when you think you’re never going to have to act on it:

‘Brexit. Conservatives didn’t think they were gonna win a majority and the lib dems would stop them having to commit to a referendum promise. They did win, they did get a referendum and …’ [Steph Leonard]

Financial Incentives that backfire:

‘There was that rat control program that led to people breeding more rats so they could hand them in and get paid :-).’ [Mark Tiele Westra]

You might be thinking of cobras in British colonial India [Tim Krap]

Special Mentions for:

0.7: ‘Not clear cut, but what about the 0.7 law campaign? Was supposed to cement x-party consensus, but has resulted in aid/devt becoming a lightning rod for r. wing criticism’ [Chris Jordan]

Then there’s this gem from Scott Guggenheim: ‘I have one from my youth as a World Banker. We were working on a large dam in Central Mexico. My area was dialogue with communities over a resettlement plan, but while at it, the team environmentalists and I had the very clever idea of a community environmental preservation campaign for one of the rare endemic cactus species. So we worked with the local elementary schools to make big, beautiful posters, launch class discussions, and promote little field trips to educate the children on how protect their environmental heritage.

Sure enough, not only was our progressive idea received with enthusiasm by the neighboring communities, but they were so thrilled to see the World Bank helping them protect their obviously valuable cactuses that they dug up all of the remaining plants to sell by the roadside before the foreign collectors could come down and seize them. Pretty much, ahem, none were left. Que pena!

One good rule for development that you can always count on is that no good intention will be left unpunished.’

And a couple that I just didn’t get:

‘Oscar voters for Moonlight’ [Faye Leone]

‘Australian marriage equality plebiscite?’ [Hugo Temby]

My overall verdict is ‘close, but no cigar’ – I still want some more examples of civil society/NGO advocacy campaigns that clearly backfired. Not ones that have no/little impact (eg Kony 2012), but actually backfire. Maybe I haven’t framed the question right. More suggestions please – and hurry up – I promised Gaia a response at the next class, which is on Friday.

The post List of your most disastrous campaign own goals – more please! appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers