Duncan Green's Blog, page 90

July 26, 2018

What did I learn from 2 days of intense discussions on empowerment and accountability in messy places?

I wish I was one of those people who can sit zen-like through a two day academic conference, smiling and

Pakistan

constructive throughout. Instead I fear I come across as slightly unhinged â fidgety; big mood swings as I get excited, irritated or bored in rapid succession.

The most recent example of my failings was a two day conference at IDS last week on the role of âexternal actorsâ (aid agencies of all stripes) in building empowerment and accountability in fragile and conflict affected settings (part of the A4EA programme). Iâll kick off with some overall impressions, then drill down on a couple of issues in subsequent posts. It was Chatham House rules, so Iâll anonymise both people and countries.

Closing Civil Society Space: since the start of the A4EA project a couple of years ago, closing space for civil society activity has become more and more of an issue. Iâm not sure that advocacy or research has kept up with the pace of events. Some of the research themes that cropped up were

What do successful defensive strategies look like, whether at local or national levels. Is there any role for external actors in preventing crackdowns and repressive legislation, and if so what?

How are civil society organizations adapting to shrinking space: is it just weakening them, or might it actually have some positive consequences (eg in reducing their dependence on aid, or forcing them to build broader local coalitions)?

If the political arena previously occupied by formal CSOs is being shrunk, what new players, if any, are expanding into it? Are they good or bad guys in terms of their attitudes to inclusion, equality etc?

Which kinds of CSOs or activity are more vulnerable to shrinking space, which less. I imagine that human and womenâs rights organizations are likely to be most vulnerable, but itâs at least worth checking

What are the implications for research methods? We heard that in some countries, even the word âresearchâ is verboten – seen as roughly equivalent to âspyingâ by suspicious intelligence services. Does closing space change the relative merits of using local v international researchers?

Does âthinking and working politicallyâ have a built-in self-destruct button? Becoming more visible, whether through bigger budgets, or the kind of research we are doing, may be a double-edged sword for TWP. Size and publicity can increase impact and uptake by new organizations and individuals â the start of a movement, perhaps. But increased visibility is likely to draw unwelcome attention from governments who see it as spilling over into interference in national sovereignty â after all (just to be provocative), doesnât Russia stand accused of âthinking and working politicallyâ in the US elections? More parochially, we heard how increased size brings greater scrutiny from donor HQs, who are more likely to demand short term results, and less likely to tolerate a long phase of thoughtful experimentation. Maybe thereâs a good reason why all this stayed below the radar for so long.

Get the right Metaphor: On one level, a two-day gabfest like this one is a group of people chucking multiple ideas, words and metaphors into a common pool. You then see which ones get picked up and echoed in the conversations. I was struck by the uptake and versatility of Donella Meadowsâ metaphor of âdancing with the systemâ: itâs difficult to be a good dancer when they keep changing the music. You learn by going to dance classes (mentoring, exchanges, shadowing), not reading a book about dancing. The thing about fragile states is that you have a wider range of dance partners (traditional authorities, armed groups etc). You get the picture. That matters because the metaphor comes with assumptions and ideas attached, in this case the importance of responding to feedback, scepticism about pre-agreed plans etc.

Research and Practice: We had a brilliant mix of researchers, practitioners, and many who are both. Even so, I heard a rumbling undercurrent of discontent: âwhy do these academics take what we instinctively do as good aid workers, then dress it up in such complex language?â

Thereâs an awkward trade-off: Intellectualize an issue and you keep the donor happy (âthanks for your framework – it helped satisfy DFIDâ, said one practitioner), and the researcherâs academic career gets a boost. But even if they learn to speak the new jargon, practitioners feel alienated and disempowered â youâve taken our work and turned it into something unrecognisable. On the other hand, if practitioners communicate in their own language and vocabulary, they may feel empowered and can spread the word, but DFID doesnât get it and neither does the academic incentive system.

system.

Getting the balance right is enormously difficult â as Einstein once said, âMake things as simple as possible, but not simplerâ. Cheers, Albert.

Weâve all bought into the standard critique of not pushing cookie cutter solutions to different contexts. Context is king. But then, how much context is enough? For some at the more anthropological end of the spectrum, you can never delve deep enough â there is always more to understand about context. But that carries a high cost â nowhere can be compared to anywhere else; everything is unimaginably complicated. Eyes glaze over.

Finally, as Kate Raworth so brilliantly demonstrates in Doughnut Economics, diagrams and toolkits are the way the aid sector frames its thinking and practice. So they are a vital way in which new ideas can be packaged and spread. Unfortunately that can also carry the seeds of its own destruction: as subtle new ideas are dumbed down into checklists and adopted as part of compliance, they kill innovation and creativity, rather than the opposite.

All in all, a pretty stimulating couple of days. And I even got to swim in the Brighton sea before breakfast!

The post What did I learn from 2 days of intense discussions on empowerment and accountability in messy places? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

July 25, 2018

Why is Latin America Going Backwards?

some worrying times for Latin America

Just a few years ago Latin America was being lauded as a success story, with stable economic growth, political stability and historical progress in addressing poverty and finally tackling the structural and historical inequality that has stymied development in the region for centuries.

Today the region is in the news for all the wrong reasons – from high profile investigations exposing rampant corruption, to economic slowdown and democratic decline. Latin America is now politically volatile, increasingly violent (with the highest levels of femicides in the world) and faces a growing migratory crisis. How did we get to this?

During the 1980s and 1990s the region endured a period of austerity, structural adjustment, and fledging democratic reform following long periods of authoritarian regimes. Poverty was unacceptably high and the region was noted for the extreme concentration of wealth and power, and exclusion and denial of basic rights for the majority of the population. The most unequal region in the world.

Latin American poverty and inequality, by year

The new millennium brought a relative golden period between 2000 and 2015, with an economic boom, fuelled by high commodity prices and a combination of growing economic opportunity, redistributive public policies, and consolidation of democratic and electoral processes, enabling a dramatic and historical reduction of poverty and inequality.

Brazil was widely considered the success story and leader in the region with wide-ranging and successful social programmes under the banners of âZero Hungerâ and âBrazil Without Miseryâ. Success was built on a combination of growing formal employment and an increase in the minimum wage and social security coverage; conditional cash transfers to women living in poverty, which got kids to school and school meals; an investment in family agriculture and food production to address food and nutritional security, access to water with thousands of domestic cisterns installed across the semi-arid regions of Brazil; promotion of women and black people rights. All of this contributed to a decline in inequality not only in income but also across gender and race. The World Bank has estimated that 29 million Brazilian people emerged from poverty between 2003 and 2014.

This was just 4 years ago, when I left Brazil. And yet today Brazil is in a state of collapse. Economic recession has been followed by a political and democratic crisis. President Dilma was ousted through an impeachment process led by the Congress. Widespread corruption scandals have followed, linked to bribes and backhanders from Brazil´s giant oil company Petrobras. Similar scandals have rocked the region with the giant Brazilian construction company Odebrecht allegedly winning contracts after handsomely paying politicians and presidents across the region. Former president Lula is in jail charged with corruption in a ploy many believe is designed to prevent him from running for president in this year´s elections, and which by many accounts he would probably win.

Neighbouring Venezuela, rocked by declining oil prices, has imploded. The funding that fuelled the parallel state set

Impeachment protests Brazil 2016

up by Chavez to address poverty, has run dry, and President Maduro, Chavez´s self-appointed successor, has been unable to maintain the same political momentum. Food shortages and hyperinflation have ensued with an increase in violence and political persecution of the opposition, which largely boycotted this year´s elections. Despite poorly contested and a barely credible poll, Maduro retained power.

The economic collapse and political crisis in Venezuela has now generated a regional humanitarian crisis, with hundreds of thousands of refugees and migrants spilling over the porous borders with Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Brazil, fleeing food and medicine shortages and economic hardship.

Nicaragua is the latest country to implode, with Daniel Ortega´s government after 11 years in power reacting violently to protest groups who are now calling for his resignation and justice for more than 300 people killed by police and paramilitary groups during peaceful protests.

The political and ideological shift toward the left between 2000-2015 opened up space for moderate and progressive social reforms across the region and for a renewed consensus around the role of the state in addressing poverty and inequality. This is now under threat and being rolled back. With several leftist options falling from grace and mired in scandals of corruption, we seem to be going back to our neo-liberal past. Country after country is resorting to austerity and cutting back its social programmes. Unsurprisingly, poverty and inequality are rebounding.

The most extreme case is in Brazil, where legislation has capped social spending for the next 20 years and has already led to widespread spending cuts on women´s rights (a 53% cut), housing (62%), climate change (72%) and food and nutritional security (76%). Millions have fallen back below the poverty line.

There are a number of factors that have reversed progress on inequality. The continued reliance on commodities and natural resources and the lack of a diversified productive base is often cited as the main economic reason. Economic growth and recession follow boom and bust commodity price cycles. The failure to shift this reliance on extractivism and generate new sources of employment must be considered one of the failures of the âgolden ageâ.

Increasingly, however, academics and development practitioners are looking at a less visible and tangible obstacle – the capture of the State by economic and political elites. The extreme concentration of economic and political power reinforces the ability to unduly co-opt, corrupt and divert the democratic process, and influence the role of the State, perpetuating measures that reinforce privilege on the one hand and inequality and exclusion on the other. This elite capture is manifested in the ability to influence public policies, fiscal systems (regressive rather than progressive), and keep wages low (one in six workers with formal employment in the region live in poverty). It also leads to corruption and an erosion of democratic process, principle and institutions.

Increasingly, however, academics and development practitioners are looking at a less visible and tangible obstacle – the capture of the State by economic and political elites. The extreme concentration of economic and political power reinforces the ability to unduly co-opt, corrupt and divert the democratic process, and influence the role of the State, perpetuating measures that reinforce privilege on the one hand and inequality and exclusion on the other. This elite capture is manifested in the ability to influence public policies, fiscal systems (regressive rather than progressive), and keep wages low (one in six workers with formal employment in the region live in poverty). It also leads to corruption and an erosion of democratic process, principle and institutions.

The UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) call it âthe culture of privilege.â Latinobarometro in its 2017 report âDecline in Democracyâ, refers to a âdemocratic diabetesâ, an invisible illness that isn´t alarming in itself but slowly kills you. 75% of Latin Americans believe they are governed by an elite that rules for its own benefit.

Power and privilege has a habit of not letting go, but they are being contested and against the odds, social movements are trying to build an alternative narrative to tackle inequality. Farmers and indigenous peoples are defying the extreme concentration of land and seeking legal protection for their access to natural resources. Women are demonstrating in the major cities across the region against exclusion and impunity of violence against women. Youth movements, seeking a future of opportunity, are rallying in the streets against corruption and abuse of power. The region is unpredictable and volatile, but not without hope.

For more, see Oxfamâs regional report : Privileges That Deny Rights: Extreme Inequality and the Hijacking of Democracy in Latin America and the Caribbean

The post Why is Latin America Going Backwards? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

July 24, 2018

What I’ve learned about how the structures of businesses determine their social mission

100 days ago. I left Oxfam to lead the World Fair Trade Organization. After seven years in Oxfam I had got hooked on one specific question: ‘are business structures that maximise power and returns for investors the only viable option?’ So now I lead a network of over 300 Fair Trade social enterprises that aim to show that business can indeed pursue a social mission. Today is my 100th day as the chief executive of the World Fair Trade Organization and it’s time to reflect on where I now stand on what businesses can and should become.

Which matters more, business structures or people?

I spent years arguing that it’s about business structure, stupid. The words of the late Pamela Hartigan rung in my ear: “The key to sustainable capitalism is reasonable profits as opposed to maximizing profits.” But if a business is structured so it must always make decisions that maximise profits, then that business is in a straitjacket. And I spent years trying to capture which structural features characterise this neoliberal straitjacket, in reports like this one with the Donor Committee on Enterprise Development and our framework in the recent paper on Fair Value developed with Oxfam policy-wiz Alex Maitland.

Creative Handicrafts

I still think structure is critical – an enabler and an indicator of a business that is focused on more than just profits. I still tout the employee-ownership models of WFTO members like Creative Handicrafts or the almost text-book example of the multi-stakeholder governance model of El Puente (producers, workers, customers and founders have equal share and power).

But since taking on my new gig I now see that the story is not so clear for smaller businesses. I’ve already met dozens of business people from across our membership – social entrepreneurs who lead successful mission-led enterprises through a variety of structures. All members have the requirement of having their social mission in their key governance documents – that’s standard (alongside a long audited list of requirements).

But it’s the priorities of the individuals leading the enterprise that are often what really makes them mission-led models of business. It’s important that structure shouldn’t inhibit this (as having impatient investors dominating the board would) but structure isn’t the only feature driving decisions in small business. I now feel that business structure becomes relatively more important as a business grows.

Businesses that will stick with their suppliers, through thick and thin

I look at businesses and I now see a dividing line I didn’t see before. I see businesses who are non-committal to their suppliers (e.g most big food brands who buy through commodity markets) and those who are truly dependent on their suppliers. This matters, because if your brand or supply chain model is inherently linked to a group of farmers

Fair trade tartan on parade in New York

or a community, you cannot just up and leave when you find a cheaper supplier. You have to support your suppliers to improve, pay them enough to be sustainable, use your voice in favour of the community’s interest. I’m now meeting more of these businesses that were deliberately set up to work with local suppliers – businesses like Sasha in India, Turqle in South Africa, Calypso in Chile or Selyn in Sri Lanka (all WFTO members) who have built business models where they cannot simply abandon their producers if they find a cheaper option. Examples like Village Works in Cambodia, who produce the official Fair Trade Tartan is also fully embedded in its community. Assessing this is possible and is part of the WFTO Guarantee System before any business becomes a WFTO member.

Profit maximising companies-like Adidas and Nike will shut down factories when there’s a cost saving to be enjoyed (if currency markets shift, governments raise costs through higher taxes or minimum wages, or a new cheaper supplier pops up anywhere in the world). This flexibility is built into their model and means they aren’t ever in a long-term partnership with the people who make their products. Stuck in the constant pursuit of ever-higher profits, Nike is looking at labour cost reductions of around 50 per cent for some shoes, leading to a bump in margins and happier investors.

That’s the way shareholder capitalism is designed, but we have a choice in shaping the kind of businesses that populate our economies. Instead, we should celebrate businesses who are fully embedded in their community, ready to stick with them through thick and thin.

But I still think business structure is central if we want to tackle inequality

The business world is diverse, but in most countries it is dominated by businesses that exist primarily to grow the capital of their investors. This is especially the case for larger companies. Profit maximisation does have incidental positive impacts: it drives investment and leads to innovation.

But it also means that business is geared to extract as much value as possible, and distribute this value proportionately to people based on the capital they have to invest. In a world where unequal distribution of capital is the key driver of inequality (according to the World Inequality Report), this essentially supercharges business to drive up inequality. While anyone can be a shareholder (through a pension fund for instance), if economic spoils are shared according to the size of capital people had to begin with, we give a growing share of the pie to the people who have the most to invest. Laws, financial markets and industry policies have made this the dominant model in many countries. But it contains a fatal design flaw if we don’t want to see spiralling inequality.

But it also means that business is geared to extract as much value as possible, and distribute this value proportionately to people based on the capital they have to invest. In a world where unequal distribution of capital is the key driver of inequality (according to the World Inequality Report), this essentially supercharges business to drive up inequality. While anyone can be a shareholder (through a pension fund for instance), if economic spoils are shared according to the size of capital people had to begin with, we give a growing share of the pie to the people who have the most to invest. Laws, financial markets and industry policies have made this the dominant model in many countries. But it contains a fatal design flaw if we don’t want to see spiralling inequality.

The post What I’ve learned about how the structures of businesses determine their social mission appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

What Iâve learned about how the structures of businesses determine their social mission

100 days ago. I left Oxfam to lead the World Fair Trade Organization. After seven years in Oxfam I had got hooked on one specific question: âare business structures that maximise power and returns for investors the only viable option?â So now I lead a network of over 300 Fair Trade social enterprises that aim to show that business can indeed pursue a social mission. Today is my 100th day as the chief executive of the World Fair Trade Organization and itâs time to reflect on where I now stand on what businesses can and should become.

Which matters more, business structures or people?

I spent years arguing that itâs about business structure, stupid. The words of the late Pamela Hartigan rung in my ear: âThe key to sustainable capitalism is reasonable profits as opposed to maximizing profits.â But if a business is structured so it must always make decisions that maximise profits, then that business is in a straitjacket. And I spent years trying to capture which structural features characterise this neoliberal straitjacket, in reports like this one with the Donor Committee on Enterprise Development and our framework in the recent paper on Fair Value developed with Oxfam policy-wiz Alex Maitland.

Creative Handicrafts

I still think structure is critical â an enabler and an indicator of a business that is focused on more than just profits. I still tout the employee-ownership models of WFTO members like Creative Handicrafts or the almost text-book example of the multi-stakeholder governance model of El Puente (producers, workers, customers and founders have equal share and power).

But since taking on my new gig I now see that the story is not so clear for smaller businesses. Iâve already met dozens of business people from across our membership – social entrepreneurs who lead successful mission-led enterprises through a variety of structures. All members have the requirement of having their social mission in their key governance documents – thatâs standard (alongside a long audited list of requirements).

But itâs the priorities of the individuals leading the enterprise that are often what really makes them mission-led models of business. Itâs important that structure shouldnât inhibit this (as having impatient investors dominating the board would) but structure isnât the only feature driving decisions in small business. I now feel that business structure becomes relatively more important as a business grows.

Businesses that will stick with their suppliers, through thick and thin

I look at businesses and I now see a dividing line I didnât see before. I see businesses who are non-committal to their suppliers (e.g most big food brands who buy through commodity markets) and those who are truly dependent on their suppliers. This matters, because if your brand or supply chain model is inherently linked to a group of farmers

Fair trade tartan on parade in New York

or a community, you cannot just up and leave when you find a cheaper supplier. You have to support your suppliers to improve, pay them enough to be sustainable, use your voice in favour of the communityâs interest. Iâm now meeting more of these businesses that were deliberately set up to work with local suppliers â businesses like Sasha in India, Turqle in South Africa, Calypso in Chile or Selyn in Sri Lanka (all WFTO members) who have built business models where they cannot simply abandon their producers if they find a cheaper option. Examples like Village Works in Cambodia, who produce the official Fair Trade Tartan is also fully embedded in its community. Assessing this is possible and is part of the WFTO Guarantee System before any business becomes a WFTO member.

Profit maximising companies-like Adidas and Nike will shut down factories when thereâs a cost saving to be enjoyed (if currency markets shift, governments raise costs through higher taxes or minimum wages, or a new cheaper supplier pops up anywhere in the world). This flexibility is built into their model and means they arenât ever in a long-term partnership with the people who make their products. Stuck in the constant pursuit of ever-higher profits, Nike is looking at labour cost reductions of around 50 per cent for some shoes, leading to a bump in margins and happier investors.

Thatâs the way shareholder capitalism is designed, but we have a choice in shaping the kind of businesses that populate our economies. Instead, we should celebrate businesses who are fully embedded in their community, ready to stick with them through thick and thin.

But I still think business structure is central if we want to tackle inequality

The business world is diverse, but in most countries it is dominated by businesses that exist primarily to grow the capital of their investors. This is especially the case for larger companies. Profit maximisation does have incidental positive impacts: it drives investment and leads to innovation.

But it also means that business is geared to extract as much value as possible, and distribute this value proportionately to people based on the capital they have to invest. In a world where unequal distribution of capital is the key driver of inequality (according to the World Inequality Report), this essentially supercharges business to drive up inequality. While anyone can be a shareholder (through a pension fund for instance), if economic spoils are shared according to the size of capital people had to begin with, we give a growing share of the pie to the people who have the most to invest. Laws, financial markets and industry policies have made this the dominant model in many countries. But it contains a fatal design flaw if we donât want to see spiralling inequality.

But it also means that business is geared to extract as much value as possible, and distribute this value proportionately to people based on the capital they have to invest. In a world where unequal distribution of capital is the key driver of inequality (according to the World Inequality Report), this essentially supercharges business to drive up inequality. While anyone can be a shareholder (through a pension fund for instance), if economic spoils are shared according to the size of capital people had to begin with, we give a growing share of the pie to the people who have the most to invest. Laws, financial markets and industry policies have made this the dominant model in many countries. But it contains a fatal design flaw if we donât want to see spiralling inequality.

The post What Iâve learned about how the structures of businesses determine their social mission appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

July 23, 2018

What can the Thinking and Working Politically community learn from peace and conflict mediation?

management/TWP from his vantage point in peace building

Wily aid practitioners have long understood the importance of adapting their programs to the political environment, and even use their activities to push politics in a progressive direction. But this magic was spun secretly, hidden behind logframes and results frameworks. Only recently has a range of programs been permitted to escape the dead hand of technocracy.

But there was one corner of the development and humanitarian world that never needed to shroud its political ambitions; those of us working on resolving violent conflicts. Donors have always understood our work could never be disembodied from politics. This field included elements of the UN, regional organisations, and NGOs, such as the one I work for: the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue.  With a new focus on development being enabled by a series of âdealsâ between different actors, it seems timely to examine the strategies used to reach peace agreements and whether they contain broader lessons for TWP/DDD/Adaptive Management.

Look for Mutually Hurting Stalemates

Much of the thinking in the TWP community has rightly focused on identifying and exploiting critical junctures. The mediation community has come to a different conclusion. Rather than fleeting moments of opportunity, look for a âmutually hurting stalemateâ in which both parties gradually accept they can no longer win the conflict outright, but instead are trapped in a cycle of unacceptable losses. When trapped in such stalemates, the willingness to accept difficult concessions is unlikely to arrive in a flash of insight, but rather will probably accumulate gradually.

Thinks About Processes, Not Just Outcomes

The striking of deals or even the building of consensus requires an ongoing negotiation process that allows the parties to build trust and converge on a mutually acceptable outcome. But perhaps more important, this negotiation processes allow leaders to reconcile themselves with the concessions they will need to make.

It’s power and politics, not just doves and olive branches.

It is common for peace agreements to contain provisions which would have been unthinkable to parties at the beginning of negotiations. But they are eventually accepted because leaders have progressively invested more and more of their own political credibility in the process. For development practitioners this means reaching out to their adversaries early, then thinking carefully about what type of negotiation process and architecture could be used to resolve the dispute. If a campaignâs goal is to secure living wages for plantation workers, it could start by convening agricultural corporations and workers on mutually beneficial issues such as productivity-enhancing technology. These types of confidence building measures can build relationships and shape attitudes enabling future deals on more contentious issues.

Engage the Potential Spoilers

Conflict polarises societies and often results in groups behaving reprehensively. Many times peace processes have excluded these groups for having unrealistic goals or simply being morally offensive. Their exclusion has often haunted peace negotiations, as these âspoilersâ seek to derail the process with violence.

For this reason when working on policy change the exclusion of regressive constituencies from negotiation processes should only be done as a last resort. While there may be actors that are implacably opposed to a reform, they are often impossible to identify without engaging them. Sometimes convincing a potential enemy of reform to only oppose a reform half-heartedly is a valuable contribution. In the words of Lyndon Johnson, it is better to have potential spoilers âinside the tent pissing out, rather than outside the tent pissing inâ

The Challenges of a Fragmenting Opposition

Conflicts are settled because groups mutually agree to behave differently in the future (share power, withdraw military forces, disarm etc). But they will only uphold their end of the bargain if they believe that their opposition is both willing and capable of upholding its own commitments. When groups fragment into smaller constituents it prevents leaders making credible commitments. This fragmentation is common among armed groups and requires peace mediators to build cohesive umbrella bodies that can genuinely speak on behalf of multiple constituencies.

While there may be times when it is expedient to fracture your opposition, there will be others where fragmentation makes it impossible to reach a successful deal . For development practitioners, this underlines the important (but awkward) task of promoting the cohesion of groups that oppose reform.

Conclusion: All of this may seem extremely transactional, with an undue focus on reaching consensus rather than fighting for justice. There may be times when progressive reform requires the total defeat of the opposition, but there are other circumstances where the most viable solution is to facilitate a deal between sections of powerful elites and sections of the citizenry. And for that, we can look to the spotted history of peace and conflict mediation for ideas.

The post What can the Thinking and Working Politically community learn from peace and conflict mediation? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

July 22, 2018

Links I Liked

Winnie Byanyima for this infographic

This is an enchanting and uplifting 45 secs. Anyone know which country these kids are in? Special props to the âlittle hype manâ.

New ”Practical Guide to Measuring Womenâs and Girlsâ Empowerment in Impact Evaluations” from the measurement geeks at J-PAL.

What Can Men do to Advance Womenâs Equality in academia? Lots of good suggestions here – add your own to the Google Doc

Nigeria, one of Africaâs two wealthiest economies, has overtaken India as home to the worldâs greatest concentration of extreme poverty.

15 leading academics, including 3 Nobel winning economist, argue that $bns of aid dollars can do little to alleviate poverty while we fail to tackle its root causes. Big critique of aid micro-effectiveness agenda, which provoked a lot of commentary and push back on social media.

Back to the World Cup. Trevor Noah just keeps getting smarter and funnier. Here he is responding to a letter from the French Ambassador on who won â France or Africa? Plus a spin-off article about what the exchange says about different attitudes to race and identity.

The post Links I Liked appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

July 19, 2018

Some whacky ideas for a future Oxfam – draft paper for your comments

actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around. That, I believe, is our basic function: to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes the politically inevitable.”

Well I seem to be in the middle of a potential Milton Friedman moment. As part of Oxfam GB’s internal discussion on its future path, my outgoing boss Mark Goldring asked me to write a paper with some crazy ideas (‘the whackier, the better’) to jolt people out of the immediate preoccupations of safeguarding and job cuts, and into broader thinking about the future roles of large international NGOs like ours.

Being told to be whacky is a bit like being ordered to be funny, but I gave it a go, putting together my 2015 paper, Fit for the Future?, some of the bonkers-and-vaguely-relevant ideas aired on this blog over the years, and adding a few new ones. Here’s the 6 page paper that is now being sent round: Fit-for-the-Future-2-for-comment-July-2018. It covers two kinds of ‘hows’ and one ‘why’. And just to be crystal clear, this is a paper written for Oxfam GB, not Oxfam International, and has no official status whatsoever!

Walls and Boundaries

When you work inside Oxfam it can feel like a fortress, surrounded by thick walls. People are either Oxfam, Exfam,

Old Oxfam?

or ‘other’. That prevents ideas and influences flowing into and out of the organization and is anathema to ‘dancing with the system’. Some ways to weaken or tear down those walls include

Open Access: every ‘product’ from evaluation data to draft papers to internal training materials should go online. Default for any written piece of work should be to publish, or else have to explain why that is a bad idea.

‘Disintermediation’, aka Oxfam getting out of the way, for example through

GiveDirectly: a button on the website lets you give money directly to people living in poverty

New Oxfam?

HearDirectly: click here to hear from families, activists, local leaders

Sponsor an Activist: forget goats or toilets, help your mum sponsor a women’s rights activist for Christmas!

Start-ups and spin offs: Time to implement the move from ‘supertanker’ to ‘flotilla’: Seed the ecosystem by spinning off 10 promising projects a year as independent start-ups, with a bit of capital and support; relinquish top-down control of advocacy by supporting ‘grey panthers’ groups to work on areas such as finance, tax or extractives.

Positive Deviance: PD shows respect for the system’s ability to solve problems, and a move away from the arrogance and hubris of the white saviour aid complex. Let’s make it standard practice, and see if it could potentially replace the project as our default way of working.

Who is Oxfam?

Women-Only Humanitarian Response Team: Creating an explicitly women-only humanitarian team would provide an explicit break with the past. It could be permanent, or a temporary measure, with the incorporation of feminist men down the line, once the required culture shift has been achieved.

Democratizing Oxfam’s Governance: One third of trustees to be elected by supporters; one third by long term partners; one third by Oxfam (eg the chair, CEO and existing trustees)? Or we could have staff representatives on the board, as in the German model?

Getting Serious on Localization: A localization commitment device: we pledge that X% (100%?) of our spend will go through genuinely local CSOs by 2022. If we fall short, we will pass the shortfall to a 3rd party organization such as Civicus, for use as a local CSO trust fund until meet our target. Oh, and we also set up and support a Fundraisers without Borders network

Is this about poverty or power?

Beyond the Project: The hivemind of aid and activism is trapped in the straitjacket of the project – linear, clunky and poorly suited to navigating reality’s rapids. In practice, we often find and support inspirational leaders, but can only do so by obliging them to come up with a project. Why not skip that bit and back individuals directly with scholarships, mentoring, exchanges etc?

A change of Why: From Poverty to Power

According to Oxfam’s website ‘Our vision is a just world without poverty. We want a world where people are valued and treated equally, enjoy their rights as full citizens, and can influence decisions affecting their lives.’

What if we made power (not just ‘empowerment’) more central? Power is the underlying force field of social change, Oxfam turns its role into leading the way in understanding, measuring and influencing the nature and distribution of power. Takes a new look at its 3 core activities: humanitarian, long term development and influencing, through a power lens. Some pluses:

Power is post-development – universal, eternal and central

Power is already what we are good at (sometimes) – see our new work on measuring women’s empowerment

So that’s the best I could manage – please add, and whackify – this is supposed to be the start, not the end, of a conversation.

Initial discussions with Oxfam colleagues have been both interesting and surprising: disintermediation and ‘from poverty to power’ have attracted the most animated discussions (Mark suggested I trademark the latter, just in case). Women-only humanitarian looks like being a marmite issue (you love it or hate it). But the best news is that people are definitely up for disruption in response to the current crisis. I hate to admit it, but it looks like Milton Friedman was onto something.

Over to you.

The post Some whacky ideas for a future Oxfam – draft paper for your comments appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

Some whacky ideas for a future Oxfam â draft paper for your comments

actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around. That, I believe, is our basic function: to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes the politically inevitable.â

Well I seem to be in the middle of a potential Milton Friedman moment. As part of Oxfam GBâs internal discussion on its future path, my outgoing boss Mark Goldring asked me to write a paper with some crazy ideas (âthe whackier, the betterâ) to jolt people out of the immediate preoccupations of safeguarding and job cuts, and into broader thinking about the future roles of large international NGOs like ours.

Being told to be whacky is a bit like being ordered to be funny, but I gave it a go, putting together my 2015 paper, Fit for the Future?, some of the bonkers-and-vaguely-relevant ideas aired on this blog over the years, and adding a few new ones. Hereâs the 6 page paper that is now being sent round: Fit-for-the-Future-2-for-comment-July-2018. It covers two kinds of âhowsâ and one âwhyâ. And just to be crystal clear, this is a paper written for Oxfam GB, not Oxfam International, and has no official status whatsoever!

Walls and Boundaries

When you work inside Oxfam it can feel like a fortress, surrounded by thick walls. People are either Oxfam, Exfam,

Old Oxfam?

or âotherâ. That prevents ideas and influences flowing into and out of the organization and is anathema to âdancing with the systemâ. Some ways to weaken or tear down those walls include

Open Access: every âproductâ from evaluation data to draft papers to internal training materials should go online. Default for any written piece of work should be to publish, or else have to explain why that is a bad idea.

âDisintermediationâ, aka Oxfam getting out of the way, for example through

GiveDirectly: a button on the website lets you give money directly to people living in poverty

New Oxfam?

HearDirectly: click here to hear from families, activists, local leaders

Sponsor an Activist: forget goats or toilets, help your mum sponsor a womenâs rights activist for Christmas!

Start-ups and spin offs: Time to implement the move from âsupertankerâ to âflotillaâ: Seed the ecosystem by spinning off 10 promising projects a year as independent start-ups, with a bit of capital and support; relinquish top-down control of advocacy by supporting âgrey panthersâ groups to work on areas such as finance, tax or extractives.

Positive Deviance: PD shows respect for the systemâs ability to solve problems, and a move away from the arrogance and hubris of the white saviour aid complex. Letâs make it standard practice, and see if it could potentially replace the project as our default way of working.

Who is Oxfam?

Women-Only Humanitarian Response Team: Creating an explicitly women-only humanitarian team would provide an explicit break with the past. It could be permanent, or a temporary measure, with the incorporation of feminist men down the line, once the required culture shift has been achieved.

Democratizing Oxfamâs Governance: One third of trustees to be elected by supporters; one third by long term partners; one third by Oxfam (eg the chair, CEO and existing trustees)? Or we could have staff representatives on the board, as in the German model?

Getting Serious on Localization: A localization commitment device: we pledge that X% (100%?) of our spend will go through genuinely local CSOs by 2022. If we fall short, we will pass the shortfall to a 3rd party organization such as Civicus, for use as a local CSO trust fund until meet our target. Oh, and we also set up and support a Fundraisers without Borders network

Is this about poverty or power?

Beyond the Project: The hivemind of aid and activism is trapped in the straitjacket of the project â linear, clunky and poorly suited to navigating realityâs rapids. In practice, we often find and support inspirational leaders, but can only do so by obliging them to come up with a project. Why not skip that bit and back individuals directly with scholarships, mentoring, exchanges etc?

A change of Why: From Poverty to Power

According to Oxfamâs website âOur vision is a just world without poverty. We want a world where people are valued and treated equally, enjoy their rights as full citizens, and can influence decisions affecting their lives.â

What if we made power (not just âempowermentâ) more central? Power is the underlying force field of social change, Oxfam turns its role into leading the way in understanding, measuring and influencing the nature and distribution of power. Takes a new look at its 3 core activities: humanitarian, long term development and influencing, through a power lens. Some pluses:

Power is post-development â universal, eternal and central

Power is already what we are good at (sometimes) â see our new work on measuring womenâs empowerment

So thatâs the best I could manage â please add, and whackify â this is supposed to be the start, not the end, of a conversation.

Initial discussions with Oxfam colleagues have been both interesting and surprising: disintermediation and âfrom poverty to powerâ have attracted the most animated discussions (Mark suggested I trademark the latter, just in case). Women-only humanitarian looks like being a marmite issue (you love it or hate it). But the best news is that people are definitely up for disruption in response to the current crisis. I hate to admit it, but it looks like Milton Friedman was onto something.

Over to you.

The post Some whacky ideas for a future Oxfam – draft paper for your comments appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

July 18, 2018

Escaping the Fragility Trap? Why is it so hard to think constructively about fragile states?

Oxfordâs Blavatnik School of Government; big name chairs (David Cameron, Donald Kaberuka and the LSEâs Adnan Khan). And I think itâs a bit disappointing. But the reasons for that are actually quite interesting and instructive.

First the positives. Above all, the reportâs recognition and ambition: recognition that fragile and conflict affected states (FCAS) are the hardest nut to crack in development, and require all the brainpower and resources possible. Ambition, in that it reckons the nut can indeed by cracked.

It has some good overall instincts, setting out in the foreword that âwhat worksâ in FCAS is âRealism, not idealism; Local, not international priorities; Reconciliation first, not elections first and Working with governments not around governments and Institution building and nation building.â Paul Collierâs influence shows in its sensible reminder that forcing countries emerging from conflict to run early elections can do more harm than good.

They do the traditional take-down of previous attempts to fix FCAS from outside, arguing that âreceived wisdom has accumulated via three different processes: quick reactions to the crises inherent to fragility; imagining that fragility has a single root cause that can be addressed by international intervention or domestic resolution; and inferring strategy for the escape from fragility from the current characteristics of Western democracies.â

So good instincts and diagnosis, although there is a tendency to set up (and knock down) straw men rather than acknowledge current debates and shifts in donor thinking â other reviewers have found little new in the report. In fact, there is a lot of rethinking going on – the kind of things I discussed last year in a paper on donor theories of change in FCAS.

The report gets in a tangle over the role of the state: âOnly governments can lift societies out of fragilityâ, it declares and sets out recommendations for âviable strategies for national leaders wishing to begin the escape from fragilityâ. But what if the government is either absent, or predatory? In time honoured policy wonk fashion, it appears to be assuming a can opener â in this case a government that is willing and to some extent able to fix things, and which needs some help from outside. Which then allows them to set forth some sensible recommendations for that  government, both on political reform and economic policy.

government, both on political reform and economic policy.

Here are the headline recommendations: when youâre reading them, ask yourselves, âwhat are the chances of this working in Syria, Yemen, Somalia or South Sudan?â

For International Actors:

Help build government that is subject to checks and balances and works for common purpose

Help build domestic security, including through a phase of international and regional security

Capitalise on pivotal moments

Focus on economic governance, not policies

Use aid to support private investment for job creation

Adopt distinctive international financial institution (IFI) policies for fragile states

Use international means of building resilience

For Domestic Actors:

Establish limited and purposive long-term goals

In the short-term, look for quick wins

Build institutions to support the private economy

Invest in urban infrastructure for energy and connectivity

Use domestic means of building resilience

The Commission was hosted at LSEâs International Growth Centre, but no-one from the International Development department (where I work) was involved, and I think it shows: the literature on the politics and political economy of FCAS is strikingly absent: no mentions of some of its leading current thinkers, as featured regularly on this blog: Sue Unsworth, David Booth, Brian Levy or Matt Andrews. Even within the LSE, no mention of some of the relevant big name profs – James Putzel, Mary Kaldor, Alex de Waal or David Keen, all of whom have written extensively on crisis states and conflict. Nor of the work of two highly relevant research initiatives â the Crisis States Research Network and CPAID (where I do a day a week).The report also fails to acknowledge all the practical experience accumulating within PDIA, Doing Development Differently or the Thinking and Working Politically communities.

states and conflict. Nor of the work of two highly relevant research initiatives â the Crisis States Research Network and CPAID (where I do a day a week).The report also fails to acknowledge all the practical experience accumulating within PDIA, Doing Development Differently or the Thinking and Working Politically communities.

Instead it looks for lessons from countries like Uganda, Rwanda and Ethiopia, which took off after magically acquiring a tin opener in the shape of a nation-building authoritarian government led by a Kagame or a Meles.

But what can outsiders (or domestic reformers) do, absent a providential, well intentioned and powerful leader? That for me is the most interesting, and urgent question, and I think if they had asked more of the researchers named above, they might have got more interesting answers. Options include:

Nothing. Accept that official aid donors in particular are helpless to work in contexts where their principal ally, the state, is not onside. When a Meles or Kagame appears, drop everything and rush to both help them transform the economy, and try to nudge them away from authoritarianism (not easy, I realize).

Hybrid institutions/Working with the Grain. Invest in understanding the institutions, both formal and informal, that exist in a given context, and find solutions that involve and strengthen them. See ODIâs great work on educational reforms in West Africa for more on that, or Brian Levyâs Working with the Grain.

Pockets of Effectiveness: look beyond the presidential palace, to identify ministries, municipalities, bits of the judiciary or other fragments of the state that are still functioning and could be viable partners.

Look beyond the state altogether: tricky for official donors, but there is a whole world of âpublic authorityâ held by non-state actors like traditional chiefs, faith leaders, civil society organizations or private sector bodies, that can be brought together to trigger processes of social and economic change.

Any other suggestions?

The post Escaping the Fragility Trap? Why is it so hard to think constructively about fragile states? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

July 17, 2018

What’s the role of Aid in Fragile States? My piece for OECD

even to skimming it yet. Will report back on the interesting bits, but in the meantime here is the piece I  contributed, on fragility and aid.

contributed, on fragility and aid.

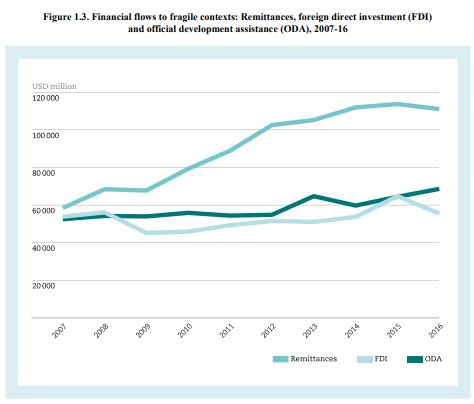

If aid is primarily aimed at reducing extreme poverty and suffering, then its future lies in fragile contexts. Recent research predicts that poverty will continue to fall in stable settings but will rise in fragile and conflict-affected settings, with poverty in these contexts overtaking the rest of the world by 2020 and then pulling away, effectively bringing an end to the current era of rapid poverty reduction. In the same vein, this report anticipates that by 2030 some 80% of the world’s poor will live in fragile contexts. As shown in Figure 1.3, aid to fragile contexts has been rising steadily although not dramatically over the last decade, increasing to $68 billion in 2016 from $52 billion in 2007.

The increasing concentration of aid in fragile contexts lays bare the difficulties facing donors. First, these are the hardest settings in which to achieve results and the most likely to produce failures and scandals. In addition, the institutional design of aid agencies often prevents them from adapting their way of working to fragile contexts. For instance, security concerns mean that staff of the International Monetary Fund cannot even visit some fragile settings. Other donor staff who are able to work in fragile environments face daunting restrictions on their movements and contacts; many are confined to heavily fortified compounds with little access to partner governments and still less to non-state players who might be able to inform decisions. Staff turnover in such environments is often high. Finally, funding cycles are often dominated by short-term humanitarian responses, making it difficult to design longer-term strategies needed to address the fragility and its deeper causes.

The challenges to traditional aid approaches run even deeper, however. Bilateral and multilateral aid agencies have traditionally seen sovereign governments as their natural partners and/or arenas of action. But in fragile contexts, states are often weak or predatory. Many other actors fill the partial vacuum of politics and administration, among them traditional leaders, faith organisations, social movements and armed groups. The actions of individuals and organisations are constrained by these different facets of what is considered public authority, and in ways that are poorly understood by researchers and still less by aid agencies. Furthermore, the instruments of aid – funding cycles, logical framework approaches, project management, and monitoring and evaluation – assume a level of stability and predictability that is often absent in such settings.

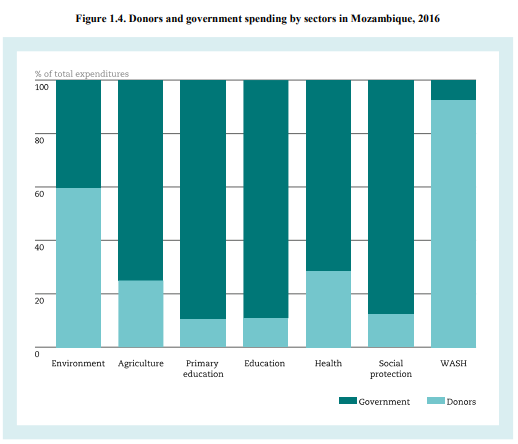

Overall, the level of aid dependence of governments in fragile contexts has fallen back slightly over the past several years. The relationship of aid to the delivery of essential services in these places raises a number of complex questions, including whether aid creates incentives or disincentives for government ownership of these services. In  best-case scenarios, the importance of aid can be exaggerated. In Mozambique, for example, health and education are overwhelmingly government-funded, with only water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) largely aid-funded (Figure 1.4.). But in worst-case scenarios, donors’ willingness to fund basic services can absolve the partner government from doing so. In South Sudan, for example, it is reported that donors fund 80% of health care and that the government funds just 1.1%.

best-case scenarios, the importance of aid can be exaggerated. In Mozambique, for example, health and education are overwhelmingly government-funded, with only water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) largely aid-funded (Figure 1.4.). But in worst-case scenarios, donors’ willingness to fund basic services can absolve the partner government from doing so. In South Sudan, for example, it is reported that donors fund 80% of health care and that the government funds just 1.1%.

One recent response to the difficulties faced by development actors in fragile contexts is to turn to the international private sector for help. However, international companies face many of the same problems in operating in these difficult settings. High levels of risk and unpredictability do not encourage long-term investment and the possibility of corruption and abuse poses serious reputational risks to brand-conscious companies.

Companies could seek to offset risk through public-private partnership agreements with donors and/or governments in fragile contexts. However, some in the development community and private sector have raised concerns about the higher cost of capital, the lack of savings and benefits, complex and costly procurement procedures, and inflexibility of such agreements in these settings.

International companies are most likely to take on the risks of operating in fragile contexts when returns are commensurately high. Extractive industries drill and mine in many such places. But extractives as a sector are capital intensive, create relatively few local jobs, and have a chequered record on human rights and environmental protection.

Local small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are the one part of the private sector that undoubtedly has a great deal to contribute to livelihoods and well-being in fragile contexts. However, SMEs often find it hard to navigate the complicated systems to access funding.

In trying to find effective ways to reduce poverty and vulnerability in fragile contexts, development actors increasingly accept that they must learn to “dance” with the system, which is a matter of grappling with the messy realities of power and politics and navigating the unpredictable tides of events, opportunities and threats. This often means abandoning or significantly adapting approaches to statebuilding and best practice developed in more stable settings.

Aid professionals have responded to these challenges by setting up networks to find ways of providing aid and support that function better in fragile contexts. One is the Doing Development Differently (DDD) network, whose 2014 manifesto set out its proposed way of working.

Aid professionals have responded to these challenges by setting up networks to find ways of providing aid and support that function better in fragile contexts. One is the Doing Development Differently (DDD) network, whose 2014 manifesto set out its proposed way of working.

DDD approaches give weight to understanding the specificities of the local context in order to be “politically smart [and] locally led” and to “work with the grain” of existing institutions. Responses to complex, messy problems need to be iterative, as donors and implementers adapt to changing circumstances and to lessons learned as their work progresses. These approaches are increasingly described as ‘adaptive management’.

Several new research programmes are also exploring the role of aid in fragile contexts and the efficacy of these new approaches. A recent analysis of theories of change among donors who seek to promote social and political accountability in fragile settings found an interesting bifurcation in thinking:

One current of thinking advocates deeper engagement with context, involving greater analytical skills, and regular analysis of the evolving political, social and economic system; working with non-state actors, sub-national state tiers and informal power; the importance of critical junctures heightening the need for fast feedback and response mechanisms; and changing social norms and working on generation-long shifts requiring new thinking about the tools and methods of engagement of the aid community. But the analysis also engenders a good deal of scepticism and caution about the potential for success, so an alternative opinion argues for pulling back to a limited focus on the “enabling environment”, principally through transparency and access to information.

In addition to the ideas outlined above, several additional options are worth exploring to try to improve the developmental contribution of financial flows in fragile contexts:

developmental contribution of financial flows in fragile contexts:

Diasporas and remittances As Figure 1.3 shows, remittances to fragility-affected countries already eclipse official development aid and foreign direct investment. They also are expected to continue to rise faster and more steadily than either of these other sources. Diasporas that send the remittances also have good knowledge of local contexts and how to support development. Some donors are exploring whether instruments such as diaspora bonds can improve the developmental impact of such flows.

Domestic resource mobilisation. Revenue raised from taxation and royalties on natural resources is growing in importance with respect to aid flows, but in many fragile contexts remains at low levels as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP). Domestic resource mobilisation offers a way to further reduce aid dependence and strengthen the social contract among citizens, the state and the private sector. Until now, however, aid agencies have failed to recognise its potential. Aid figures reported to the OECD suggest only 0.2% of aid to places affected by fragility or conflict in 2015 and 2016 – a trifling USD 116 million in 2015 and USD 110 million in 2016 – was dedicated to technical assistance for domestic resource mobilisation.

Localisation. Pushing power and decision-making as close as possible to local levels makes good sense in fragile contexts to deal with the enormous variations in conditions over space and time. So far, the localisation agenda has been more apparent in statements than action, however.

Duncan Green, London School of Economics and Political Science

Tomorrow: why I don’t think much of the report of the Commission on State Fragility

The post What’s the role of Aid in Fragile States? My piece for OECD appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers