Duncan Green's Blog, page 101

February 14, 2018

New Report from UN Women argues that Universal Childcare can unlock progress across multiple SDGs (and costs it)

Silke Staab

(left) and

Ginette Azcona

introduce their new report on gender and the SDGs,

Silke Staab

(left) and

Ginette Azcona

introduce their new report on gender and the SDGs,  published yesterday

published yesterday

UN Women has just launched its first monitoring report on gender equality and the SDGs “Turning promises into action: Gender equality in the 2030 Agenda”. The report offers the most comprehensive review to date on how gender equality features in the 2030 agenda, the massive challenges in making progress on it, and what countries need to do to bring about meaningful change in women and girls’ lives.

Having gender issues well represented in the Agenda is a huge win for women’s organizations, and as a result, among the 17 goals, 169 targets, and 232 indicators, 54 are gender-specific. It is sobering to realize that of that total, we have good data coverage for only 10. There is no question that challenge number one is improving the availability of gender data (something that we have been saying for years, but which has been given a very helpful push through the SDGs).

But, more than data availability, the policy challenges are huge, especially for developing countries. The Agenda requires progress on repealing discriminatory laws (which UN member states set a deadline for back in 2005); providing comprehensive services to address violence against women (when not even the wealthiest countries are doing this adequately); ending child marriage; reducing women’s unpaid care work burdens, and so on.

There are those who argued for a much smaller SDGs framework – a few, more tightly-focused goals that would get governments’ attention. In the end, human rights and universalism won out; and that was the right outcome – why should women and girls choose between not living in poverty, going to school, being able to decide if and when to have children and living a life free of violence and discrimination? In any case, they are all linked.

There are those who argued for a much smaller SDGs framework – a few, more tightly-focused goals that would get governments’ attention. In the end, human rights and universalism won out; and that was the right outcome – why should women and girls choose between not living in poverty, going to school, being able to decide if and when to have children and living a life free of violence and discrimination? In any case, they are all linked.

And it is precisely these linkages that provide the key to making progress on the 2030 Agenda. What are the policies that unlock change across several goals, that leverage change in one area, with massive ripple effects to others, that benefit women and girls, but also broader societies?

One of the answers is: universal childcare services. Good quality, universal and affordable childcare services reduce women’s unpaid care work (target 5.4) and enable mothers to access decent quality work because they can leave their children safely (8.5); ensure that children get at least one good meal a day (2.2), prepare them for school in the crucial and neglected early years (4.2), particularly those from disadvantaged households (10.3); and can create decent jobs in the social service sector, which tend to be taken up mostly by women (8.3).

This one policy could also have a dramatic impact on women’s poverty. In our report, we analyzed household surveys from 89 countries, finding that in their prime reproductive years (ages 25-34), women are 22 percent more likely to live in extreme poverty than men. In the years when the amount of unpaid work they do is largest, in the absence of support from governments to share this burden, women pay the price in terms of their economic security and rights.

But how are developing countries meant to afford luxuries like free universal childcare services? We did some costing in South Africa for the report, and there’s no point in pretending that these services are cheap – we reckon they come to about 3.6 percent of GDP. South Africa currently spends about 6 percent of its GDP on education; and about 4.2 percent on health, so it’s an expensive additional investment. But, according to our analysis, more than one third of the cost can be recouped through reduced social security bills and increased tax yields (because more mothers are working; and 2-3 million new jobs are created). And none of these figures include the benefits of having school-ready, well cared for children, and the potential reductions in poverty among women.

third of the cost can be recouped through reduced social security bills and increased tax yields (because more mothers are working; and 2-3 million new jobs are created). And none of these figures include the benefits of having school-ready, well cared for children, and the potential reductions in poverty among women.

While we’re talking about affordability, in the week in which activists are attending the first global conference on tax and the SDGs in New York, it is also worth noting that tax is a feminist issue. The value of outflows from developing countries ($3.3 trillion) is 2.5 times the amount of resources flowing in ($1.3 trillion). In comparison, donor spending on gender equality ($40.2 million) is a drop in the ocean. Stopping outflows, increasing tax revenues and ensuring that corporations pay their fair share of tax would provide all the resources and more to make the kind of investments we need to see in childcare services, for everyone’s benefit.

Will the SDGs make a difference? The jury is still out, but the report has some proposals for how accountability can be strengthened. As Duncan has pointed out, in the case of the MDGs we never had the longitudinal research on change and policy processes at global or national level to answer that question. This time around, we are commissioning country level research on how the SDGs have been taken up and are shaping national level policy agendas. This will be featured in the next edition of the report, so stay tuned.

February 13, 2018

A global X ray of the world’s budget processes shows progress has gone into reverse

I dropped in on the London launch of the Open Budget Survey 2017 last week – I’ve been helping its creator, the  International Budget Partnership, update its strategy. The survey has been running since 2006 – this is its sixth round. It now covers 115 countries, covering 93% of the world’s population, and assesses governments on their transparency, independent oversight of the budget process and public participation. Both the content and the pageantry around the launch were striking.

International Budget Partnership, update its strategy. The survey has been running since 2006 – this is its sixth round. It now covers 115 countries, covering 93% of the world’s population, and assesses governments on their transparency, independent oversight of the budget process and public participation. Both the content and the pageantry around the launch were striking.

First the main finding: after steady improvements in previous rounds, the average score fell back for first time. There was a particularly steep reversal of previous gains in Sub-Saharan Africa, where 22 out of 27 countries had scores falling from 2015-17, 15 of them significantly so. Why? Vivek Ramkumar from IBP was disarmingly honest – ‘we frankly don’t know’. They’ve run the numbers and found no correlation with human development, oil revenue or changes in governments. Is it linked to closing civic spaces? The rising influence of China? So far, the only correlation they have found is an intriguing one – governments that had recently issued bonds on international markets were more transparent.

Warren Krafchik, IBP’s director, emailed me a few hypotheses of his own:

At some point, it gets harder especially politically (but also technically) for governments to produce and publish information. It seems to be somewhere between 40 and 60 out of 100 on the Survey – the point at which information about state owned enterprises, debt and borrowing, and contingent liabilities starts to count. Also, the fact that several countries produce this information but do not publish it strengthens the case about the political drivers. It is easy politically to publish information up to 40 out of 100, then the interests of vested interests inside and outside government kick in, and can overpower government champions.

Several of the countries that made big leaps in transparency in the late 1990s/early 2000s to become champions, such as South Africa, India, Brazil, and Mexico were responding to regime changes, fiscal/debt crises, and the perceived need to satisfy international and local creditors, and the private sector more generally. The private sector though – and many donors (such as the World Bank) – have relatively low thresholds/demands for transparency. Policy certainty is much more important. The Bank for example only requires countries to publish their budget, which 95% of countries already do. So, pressure from these constituencies tends to decline at a relatively low level of transparency.

At present, the demand for open budgeting from civil society is not yet sufficient to replace these other drivers. A gap therefore emerges that allows countries to slip back without too many negative repercussions. The demand from civil society for budget data is still relatively weak, disaggregated, and fragmented. Civil society was not a strong driver of the first wave of transparency improvements – and is not yet strong enough to drive deeper transparency and participation. I am not referring here to the lack of analytical users, but the absence of strong, broad, powerful and organized demand for transparency/participation in the budget. It is still a niche civil society issue – and even that niche is fragmented.

Speakers in the audience also suggested declining aid dependence (Mozambique) or a shift to dependence on Chinese aid (fewer strings). Finally, someone pointed out a change in the OBS methodology, requiring countries to make key documents available on line and on time. That’s a positive change, but many African government websites are particularly clunky and moving the goalposts in this way explains about half the decline in the continent.

Speakers in the audience also suggested declining aid dependence (Mozambique) or a shift to dependence on Chinese aid (fewer strings). Finally, someone pointed out a change in the OBS methodology, requiring countries to make key documents available on line and on time. That’s a positive change, but many African government websites are particularly clunky and moving the goalposts in this way explains about half the decline in the continent.

So much for the content, what about the pageantry? The turnout attested to the pulling power of the transparency and accountability movement: Indonesia’s finance minister on video, Georgia’s in person, along with the new DFID Minister for Africa Harriet Baldwin, and Rachel Glennerster, the new DFID chief economist, moderating.

Why were they all there? The Georgian Finance Minister was in no doubt: ‘This is part of our strategy to make Georgia a regional hub. We have no mineral resources, and we want to join the EU. Making governance more open, more business-friendly is vital.’ Which also attests to the power of league tables – Georgia has leapt from a dismal rating to 5th (just below Norway) and they are letting everyone know about it.

More generally, the OBS shows the traction that can be generated by an index based on painstaking research, with a sharp focus, which works with the grain of donors. But at this point, I must confess, I have a kind of Groucho Marx syndrome by proxy, which means I always worry about clubs that are too popular with the rich and powerful. Is this club so full because it isn’t really asking governments or powerful players to do much that would rock the boat? Who benefits from all this transparency? Investors certainly love it – a woman from Blackrock on the panel explained that it helps them assess country risk. I’ve got nothing against the right kind of foreign investment, but it seems a long way from the lives of poor communities in many countries.

Putting such qualms aside, there were some important insights for activists:

Lack and skewed timing of oversight: Over 40% of legislatures did not make a single amendment to budget submitted by executives. When they do, they tend to focus on the initial proposal, not implementation, so executives have got skilled at fiddling with the budget after it’s been approved, safe in the knowledge that no-one will spot it (the media have the same short attention span as parliamentarians on budget issues).

A Ugandan CSO rep pointed out that CSOs always demand the release of more data, but the key issue is that the way that information is presented has to be useable – eg a simplified ‘citizens’ budget’, and a predictable budget publication cycle so that CSOs can prep in advance.

that information is presented has to be useable – eg a simplified ‘citizens’ budget’, and a predictable budget publication cycle so that CSOs can prep in advance.

Lots of governments have the rights kinds of budget documents but simply don’t make them public – there’s a quick win for activists in persuading them to simply press the button and upload them on their websites.

Finally, the next generation of transparency activism has to go local. In the slightly tongue-in-cheek words of Vivek ‘In an ideal world, citizens would be eagerly awaiting the latest budget report. That doesn’t happen; public mobilization often requires a very specific issue, often at community level – is my school/hospital working?’

And here’s the league table:

February 12, 2018

How can a gendered understanding of power and politics make development work more effective?

Helen Derbyshire,

Helen Derbyshire,

Sam Gibson, David Hudson and , (left to right) all researchers from the Developmental Leadership Program (DLP) introduce some new work on gender and politics (and win the prize for the most authors on a single FP2P post).

Sam Gibson, David Hudson and , (left to right) all researchers from the Developmental Leadership Program (DLP) introduce some new work on gender and politics (and win the prize for the most authors on a single FP2P post).

There have long been concerns that the ‘Thinking and Working Politically’ and ‘Doing Development Differently’ movement is a bit gender blind. Which is bizarre because no credible political analysis can ignore the kinds of power imbalances revealed by looking at gender inequality.

Now a number of governance and politics researchers are starting to address the gap. ODI and CARE have recently  published some excellent work on women’s leadership and adaptive management and gender, OECD have published a paper on gender equality in fragile settings, and GADN are about to release a paper on Political Economy Analysis, gender and monitoring and evaluation.

published some excellent work on women’s leadership and adaptive management and gender, OECD have published a paper on gender equality in fragile settings, and GADN are about to release a paper on Political Economy Analysis, gender and monitoring and evaluation.

At DLP, we have launched a suite of research on the issue. The project is called Gender and Politics in Practice. The research question is: how can a gendered understanding of power and politics make development work more effective? Our take was that many development programs tend to look at gender issues and politics separately. So, through a number of in-depth case studies – looking at women political leaders in the Pacific, labour reform in Vietnam’s garment industry, and (in partnership with The Asia Foundation), a paper on transgender empowerment and social inclusion in Indonesia – along with 14 short case studies of development programmes, we sought to understand how development workers could better incorporate gender aware and politically informed approaches.

What did we learn? We set out 5 key lessons in a project Briefing Note, which are accompanied with a series of guidance questions for practitioners. It is meant to be practical. The lessons are: work with locally-legitimate actors; combine political and gender analysis, and use it; frame developmental goals, including gender equality, in locally-appropriate ways; collect the right data and work to realistic timelines when seeking to shift gender norms; and finally, shape management systems to encourage staff and local partners to work in politically informed, gender aware ways. But there were a few other interesting takeaways.

What did we learn? We set out 5 key lessons in a project Briefing Note, which are accompanied with a series of guidance questions for practitioners. It is meant to be practical. The lessons are: work with locally-legitimate actors; combine political and gender analysis, and use it; frame developmental goals, including gender equality, in locally-appropriate ways; collect the right data and work to realistic timelines when seeking to shift gender norms; and finally, shape management systems to encourage staff and local partners to work in politically informed, gender aware ways. But there were a few other interesting takeaways.

First, over the course of doing the research, it struck us that practice was way ahead of theory. Many programme staff, managers, and practitioners were already doing excellent work to bring together politically informed and gender aware approaches. For example, MAMPU (the Australia-Indonesia Partnership for Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment) was politically informed from the outset, identifying partner organisations with a record of influencing change and including them in the program design processes. In Nigeria, two programmes – Voices for Change and SAVI – have been using values-based recruitment system to get staff with the right ethos as well as skills. These programme case studies are summarised in From Silos to Synergy.

Hilda Heine

Programme staff are often put into the shade by local politicians and leaders. Ceridwen Spark, John Cox, and Jack Corbett’s paper details how three Pacific leaders became the first women in their respective countries to reach the top – Hilda Heine, the President of the Marshall Islands, Fiame Mata’afa, the Deputy Prime Minister of Samoa and Dame Carol Kidu, who was Leader of the Opposition in Papua New Guinea. They did so through a combination of political savvy, nous, and courage.

Second, those who identify as being politically savvy often put great store on the

Fiame Naomi Mata’afa

feasibility of political reforms. But what if going for what is politically feasible actually reinforces the status quo? Many of our cases made this trade-off explicit. We concluded that a gender or normatively-focused approach to development is a welcome counter-balance to a potentially Machiavellian focus on political feasibility.

Carol Kidu

Third, often the best way of working on gender is to work obliquely – maybe not even talking about gender explicitly – and integrate gender into mainstream programmes rather than focussing on small-scale training or awareness raising among relatively small segments of society. Alice Evans’s paper on The Politics of Better Work for Women makes the case for more transformative social change through supporting institutional reforms in predominantly female industries, such as Vietnam’s garment sector.

Finally, it was hard not to conclude that, on balance, political and governance experts have more to learn from women’s groups and gender advocates than the other way around; although that’s not always the case.

February 11, 2018

Links I Liked

Noah’s Ark destroyed by flood. Really.

Fancy a week in Bologna in June learning about Adaptive Management and the implications for Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning (MEL)? I’m running a summer school with two of the sharpest minds in Oxfam, Irene Guijt and Claire Hutchings.

For obvious reasons, I am not going to comment on the current furore over Oxfam in Haiti. Here’s the latest press release, and my boss Mark Goldring on Channel 4 News.

Five lessons for researchers who want to collaborate with governments and development organisations but avoid the common pitfalls, by Susan Dodsworth and Nic Cheeseman

Big-screen musical tells story of ‘Pad Man’ – welder Arunachalam Muruganantham, who became a pioneer for menstrual health. And the producer has the glorious name of Twinkle Khanna….

Laurence Chandy draws attention to this ‘striking chart’. Note (i) how much higher Africa stands in 1950 relative to Asia; (ii) how modest the gains from the 2000s/Africa Rising era appear; (iii) Asia’s rapid and relentless advance since 2001; and (iv) Africa’s sharp dropping off the pace since 2009.

Laurence Chandy draws attention to this ‘striking chart’. Note (i) how much higher Africa stands in 1950 relative to Asia; (ii) how modest the gains from the 2000s/Africa Rising era appear; (iii) Asia’s rapid and relentless advance since 2001; and (iv) Africa’s sharp dropping off the pace since 2009.

What works to reduce child marriage? Interesting Save the Kids experiment in Bangladesh found cash transfers worked, but empowerment programmes (safe space, rights education etc) didn’t. So does empowerment not work, or is the problem not with the girls in the first place?

Is it possible for everyone to live a good life within our planet’s limits? Short answer is no. But you can check for yourself on this useful country-by-country doughnut interactive website from Dan O’Neill.

‘We found that the growth and consolidation of the Sicilian mafia is strongly associated with an external surge in the demand for lemons from 1800 onwards after the discovery of the effective use of citrus fruits to prevent scurvy’

Redrawing stereotypes – simple, brilliant and I’m guessing, transformative for these kids

February 8, 2018

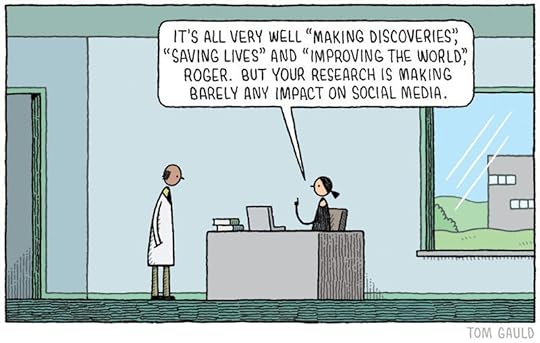

9 bad things you do (but know you shouldn’t) in research communications

Guest post by Caroline Cassidy (left) and Louise Ball

Guest post by Caroline Cassidy (left) and Louise Ball

Over the years, at ODI’s Research and Policy in Development (RAPID) programme, we have worked with an array of researchers, communicators, practitioners and policy-makers, trying to make head and tail of how to get evidence to influence or inform policy. Reflecting on how far we’ve come, we realised that there’s a ton of good advice out there on communicating research for policy. But what we often don’t talk about is the things that go against that advice, which….cough cough… if we’re honest, we all do. At least sometimes. For example…

Describe your research audience as ‘policy-makers, practitioners and the public’. You know you should be more specific, but no one seems to be questioning it. And, well we want to reach influential ‘people’. Next time, try asking: if you could get five people to read it, who would they be?

Describe your research audience as ‘policy-makers, practitioners and the public’. You know you should be more specific, but no one seems to be questioning it. And, well we want to reach influential ‘people’. Next time, try asking: if you could get five people to read it, who would they be?

Publish a long list of recommendations that are highly general, unrealistic, or both. Another common recommendation ‘faux-pas’ is to tell policy-makers what they ‘should’ to do. Read these three tips for presenting research to governments – and why it’s sometimes like being nice about an ugly baby!

Sign up to produce 20 publications for a 12-month project. Sometimes researchers are under such pressure to publish publish publish and in the rush to get strategies and plans locked down you promise the world. Quality over quantity anyone? As our colleague says, ‘not every policy problem has a report shaped solution’.

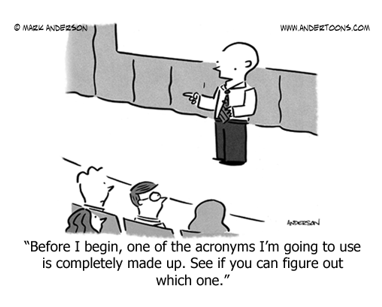

Every other word is an acronym. As long as you spell them out in full the first time it’s ok right?! If we had one  wish from the communications fairy it would be to kill acronyms for good…

wish from the communications fairy it would be to kill acronyms for good…

Send your research to 100s of people, and never follow up. There is no denying that this happens all the time. We vote to limit the word ‘dissemination’ in international development – good communication is about engagement and is multi-directional. If we all just followed up a little bit more, surely we might see more change happen?

Hail download numbers and other vanity metrics when reporting on your research ‘successes’. Even though you know it doesn’t tell you (or your donor) very much, but it’s so easy to get the stats and well…surely page views mean that someone out there is interested!? Try this toolkit on monitoring and learning from communications for other indicators that could tell you more.

Produce a video, podcast or infographic because ‘we have left over budget or/and it would be cool’. Now we don’t want to discourage doing this type of thing – it can be a totally brilliant way to reach your target audience, but it’s never a good idea to do any type of communications just for the sake of it! Strategic is the word.

Death by PowerPoint. Many have written about this over the years, many have tried to make things better (cue the birth of Prezi and Ted Talks). And yet….how many times did you want to take that nap at the last conference you attended? Less is definitely more with presentations, particularly when it comes to the text part.

Death by PowerPoint. Many have written about this over the years, many have tried to make things better (cue the birth of Prezi and Ted Talks). And yet….how many times did you want to take that nap at the last conference you attended? Less is definitely more with presentations, particularly when it comes to the text part.

Whack in a photo, you haven’t got time to look properly, this one will do. This is something that often just passes by any scrutiny. And yet, as this twitter chat showed, photography use is SO important and bad use could be reinforcing outdated development clichés.

This is just a short list we have put together – there must be more out there… comments box for any examples you have!

February 7, 2018

Development Studies is fun, but is there a job at the end of it?

true?

Studying development is fascinating, but will there be jobs for students once they graduate? I chaired a careers panel for LSE students recently, where a variety of alums, now rising up the greasy poles of the aid industry, came back to share their thoughts.

One recurring theme of the evening was the kind of skills and knowledge that will be needed if the aid industry lives up to its promises and heads South, giving priority to local organizations in humanitarian response, pushing power and resources down to developing country affiliates in INGOs.

At least half of the students in the room were from developing countries, and they will duly head off to work in government or local organizations. But what about the Europeans and North Americans – is aid still a career in those countries?

Our conclusion was that the answer is yes, but the careers and skills required are likely to look very different. The old days of the white man in shorts, heading off to be an expat and running projects, look numbered. Good thing too. Those jobs will be done by local organizations, or local staff in international organizations, who are far better placed to ‘dance with the system’ of local power and politics.

But lots of other roles will remain, including:

Campaigns and Influencing: already a growth area in the INGOs, there will still be plenty of things to do on global collective action problems like climate change and tax havens, and on northern skulduggery – corporate misbehaviour, arms trade, abuse of refugees etc. But campaigning within developing countries will, quite correctly, be run and decided by local organizations and staff. Not much role for whitey there.

Campaigns and Influencing: already a growth area in the INGOs, there will still be plenty of things to do on global collective action problems like climate change and tax havens, and on northern skulduggery – corporate misbehaviour, arms trade, abuse of refugees etc. But campaigning within developing countries will, quite correctly, be run and decided by local organizations and staff. Not much role for whitey there.

Soft skills like facilitation/ convening and brokering: one increasingly recognized role for outsiders is to act as an honest broker, bringing together different local players in search of solutions to particular problems. My favourite example is our work on water and sanitation in Tajikistan. Facilitation is just one example of the soft skills that will increasingly be needed. It’s not about digging wells or building schools (why would you ask foreigners to do that?)

That echoed a recent study on ‘The Career Paths of International Development Studies Graduates in Canada’, which surveyed nearly 2,000 graduates, with an average age of 26, and concluded:

‘The skills and competencies that IDS grads identified as most important for finding a job included the transferrable skills of writing, communications, interpersonal and cross-cultural communications and especially networking. Respondents emphasized repeatedly that finding a job requires the capacity to build strong professional networks.’

Private Sector: as long as there is global trade and investment, there will be a need for advocacy to improve how it works for poor people, whether as producers, consumers or affected communities. Engagement with big international companies will need to involve local people, obviously, but also those who can mobilize opinion in companies’ main markets.

Fragile and Conflict states: these are the places where aid is likely to remain a significant player, and when states are absent or predatory, localization is likely to be harder. Unfortunately, they are also the hardest places to get anything done! Lots of opportunities for research and practice there (I’m involved in two such exercises, led by LSE and IDS).

are absent or predatory, localization is likely to be harder. Unfortunately, they are also the hardest places to get anything done! Lots of opportunities for research and practice there (I’m involved in two such exercises, led by LSE and IDS).

Tech: our speakers were ambivalent on this. On the one hand, silicon valley types think they can solve just about any development problem with a suitable app; on the other hand, there are loads of local geeks and startups in just about every country, who are better placed to understand local context and needs.

But overall, I still worry about how many northerners see development studies as the start of a career, when the whole North/South aid frame that underpinned the creation of ‘development studies’ is becoming increasingly redundant. The Canadian report concluded that you should study development for your soul, more than your future wallet:

‘IDS graduates experience significant challenges in breaking into the job market, particularly in the international development sector. Just 19.2% of IDS grads reported that their jobs were directly related to international development, while almost 40% reported that their jobs were not related at all. However, respondents also reported that regardless of their careers, their IDS educations had profound impacts on their world views and their ongoing values and behaviours as global citizens.’

For more background on careers in development, check out Maia Gedde’s book – still the best thing I’ve come across.

Please add links to other advice and tips in the comments section.

February 6, 2018

What does ‘Dignity’ add to our understanding of development?

Guest post from Tom Wein, of the Busara Center for Behavioral Economics, based in Nairobi.

Is your program respectful? How, exactly, do you know that? Did you ask people?

Development aims to give people better lives. In doing so, we mainly aim to increase wealth and health – in part because we can measure those outcomes with ease. But there’s more to a good life than spare cash and extra years. We’ve made strides in measuring wellbeing, capabilities, and even stress. If there is something important to people’s lives, we should measure it. After all, donors will fund only what we can measure.

One glaring hole stands out to me: we often ask each other if our programs respect people’s dignity – but do not ask those who actually use the program. When it comes to dignity, we could develop measurement tools to make that easy – but we haven’t, at least not yet.

What do we mean by dignity?

One reason we don’t yet measure dignity is a glut of clashing definitions. It’s a tricky philosophical concept, and everyone from Augustine to Eleanor Roosevelt has an opinion. After spending more of my Christmas break reading Kant than I would care to admit, and with the caveat that this is a work in progress, here is how I currently conceptualize dignity:

Dignity is a universal, characteristic quality of every single person.

Simply because each person has dignity, they are entitled to respect. You can make a claim on others that you be treated with respect.

Dignity is inalienable. Your dignity can be offended against, but it cannot be lowered or taken away, no matter how badly you are treated.

This is one of the two main ways of talking about dignity – a ‘moralized’ version of dignity. The other way of talking about dignity is the ‘merit-based’ conception. When we describe some lordly ruler as having dignity, we are using the merit-based form. We make an appraisal, and decide how much respect they are due. In the merit conception, this ruler could be stripped of their dignity, and we would owe them no respect at all. The moralized form I’m talking about is different – everyone has it, it cannot be reduced or removed, and respect is always due.

Much of this draws on Remy Debes’ excellent book, ‘Dignity: A History’, and especially the chapters by Oliver Sensen and Stephen Darwall. There are a whole host of issues they discuss, and that deserve more reflection, but that perhaps is for a later piece of writing. For now, let’s say that if we can arrive at a good definition, we have the seeds of a measurement strategy.

What would measuring dignity do to development?

Get this right, and I think it changes our programs. Constant claims are made, that some program or other is specially respectful – or degrading. That is particularly true of cash transfers. Cash advocates say it is a uniquely respectful form of aid, because it confers agency. Detractors fret that it has patronizing echoes of Victorian alms-giving. A good measure of the impact of cash transfers on dignity would go some way to solving that debate.

Measuring dignity should make for programs that work harder to give aid recipients agency, equality and individuality. We could let people choose how often or where they receive aid. We could hire more from the communities we seek to help. And where we can’t – where there are good reasons of scale and efficacy for delivering aid as we currently do – we would have a better idea of the damage done. That damage is real already – it’s just that right now we don’t count it.

More discussed than defined – a collection of recent dignity headlines

Can you help?

At the Busara Center, where I work, we’ve used a first draft of a dignity measure. That was for Jeremy Shapiro’s new paper, ‘The impact of recipient choice on aid effectiveness’. Now we want to develop that into a series of more careful questionnaire scales. Any measure is surely imperfect, but equally surely a flawed measure beats not trying at all.

To do this right, I’m going to need some help. There are four big questions in my mind, and an awful lot of brainpower among the readers of this blog. If you could help me answer them, I’d be very grateful indeed:

Is this a good idea? Is measuring dignity important in development? Are there more urgent measurement challenges we are missing?

What conceptual or logical problems did you see in my description of dignity?

Is this description of dignity relevant everywhere, or specific to some cultures? What contextualization, translation or local cultural problems might this work face?

What measurement challenges do you foresee? What measurement ideas do you have?

I look forward to hearing from you – to chat about dignity, or behaviour in development, you can write to me at tom.wein@busaracenter.org

February 5, 2018

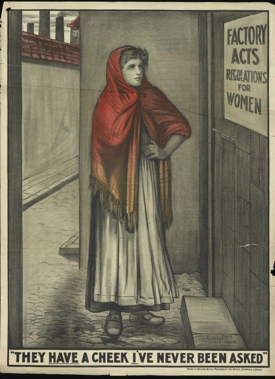

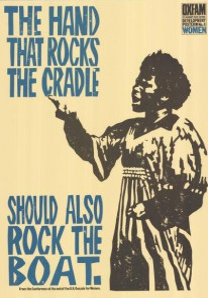

100 years after women got the vote, why is #StillMarching as central as ever to human progress?

Oxfam’s Emily Brown on today’s 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage in the UK

Today marks 100 years since some women in the UK first gained the right to vote. The People’s Representation Act of February 6th 1918 represents both a historic milestone in the post-war opening of public and political spaces to women, but also a move designed to keep a meaningful transfer of power to women to a minimum for the time being. It took another 10 years for all women to get the vote, rather than the first, privileged minority of property-owning 30+ year olds.

One hundred years on, 32% of UK Parliamentarians and 33% of local councillors are women. Respectable progress of sorts, no?

Well no…not really. As the Centenary Action Group, a coalition of over 70 women’s organisations, political parties, individuals and action groups campaigning under the #StillMarching banner observe, much more needs to be done to overcome the deep physical, cultural and institutional barriers required to deliver real change for women in the UK and worldwide. The Fawcett Society’s recent Local Government research found that just 17% of UK local councillors are led by women, 40% of women councillors have experienced sexism from within their own party, and half of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic women councillors have experienced racism and sexism. Just 4% of local councils in England today have a maternity, paternity or parental leave policy for councillors.

“There is great emphasis on women coming forward to stand but what we won’t stand for is the adverse political system and culture they are walking into. Systems and culture have to change….Our system of politics is failing to be relevant to women’s lives, actively putting them off.” Sam Smethers, Chief Executive, Fawcett Society

So why is #StillMarching relevant to us FP2P wonks? It matters because, as ‘Sausagegate’ here on this blog only a few weeks ago illustrated so starkly….the continued dominance of public spaces and debate – in the UK and globally – by male voices and faces means that the personal-is-political, social, economic and environmental issues that matter to women have a much harder chance of being heard – let alone making it into the cut when decisions about money are being made. And, when women by nature of their race, class, age or sexuality for example are not part of the groups in society with the most power, they, like young, black, minority ethnic and working class men, are even less likely to make it into the decision-making places and spaces that matter.

So why is #StillMarching relevant to us FP2P wonks? It matters because, as ‘Sausagegate’ here on this blog only a few weeks ago illustrated so starkly….the continued dominance of public spaces and debate – in the UK and globally – by male voices and faces means that the personal-is-political, social, economic and environmental issues that matter to women have a much harder chance of being heard – let alone making it into the cut when decisions about money are being made. And, when women by nature of their race, class, age or sexuality for example are not part of the groups in society with the most power, they, like young, black, minority ethnic and working class men, are even less likely to make it into the decision-making places and spaces that matter.

‘You cannot easily fit women into a structure that is already coded as male; you have to change the structure. That means thinking about power differently. It means thinking collaboratively, about the power of followers as well as leaders.’ Mary Beard, Women and Power, a Manifesto

As long as the power and institutions across our development sector are ‘man-shaped’, the diversity of women’s voices will remain largely invisible. This invisibility keeps poor women poor; by prioritising, for example, large-scale physical infrastructure projects over investments in household water, energy systems and care services that would reduce and redistribute the unpaid care and domestic work of so many millions of women; by relying on the views of a sole male community leader to establish ‘whose vulnerability’ qualifies them for humanitarian food aid; and through shamefully large numbers of multi-million dollar proposals promising that yet more citizens “especially women and other marginalised groups…..” will be empowered and transformed without a single penny being budgeted for gendered analysis, expertise or local partnerships.

“There are 22 in our council. We women are only 8… the men are noisy but not effective. If men are not accounting, we will. We’re showing a different way of doing things.” Local Councillor, Kitgum, Northern Uganda

Women’s rights activists worldwide and their allies, like Oxfam, have long held that not only is men’s unquestionable power to shape our world alone not right, but that…let’s be honest, it ultimately results in poorer quality, badly-informed development practice and outcomes.

power to shape our world alone not right, but that…let’s be honest, it ultimately results in poorer quality, badly-informed development practice and outcomes.

As Hans Rosling put it: “Poor women are smart…they have to be, otherwise they’re dead.” We ignore their experiences and their skills at our peril….. and to the detriment of more thoughtful, inclusive, and ultimately more impactful development work.

A paper published by Oxfam next month seeks to make a powerful development case for more and better investments in accompaniment to women activists and leaders, and to women’s rights organisations and movements worldwide. Because our long programme investments and experience tell us that when women activists and leaders are supported to work together – with their male allies and partners – to get behind policies and laws that promote better lives for all, we see more money, and more and better public services.

The numerous examples we draw on – from Oxfam’s own, and so many others’ thinking, practice, research and learning – offer inspiring and convincing alternatives to oppressive forms of power and leadership. These, more transformative leadership approaches are not only possible; they are already happening:

In Nepal, for example, 42% of nearly 2,000 women members of Oxfam’s Raising Her Voice ‘community discussion classes’ reported feeling able to influence the village and district development councils to allocate financial support for the promotion of women’s interests – compared to just 2% of respondents from comparator villages.

Analysis of 181 peace agreements signed between 1989 and 2011 found that…‘peace processes that included women as witnesses, signatories, mediators, and/or negotiators demonstrated a 20% increase in the probability of an agreement lasting at least two years. This increases over time, with a 35% increase in the probability of a peace agreement lasting 15 years.’

And this from a 2016 evaluation of Oxfam’s ‘AMAL’ Women’s Participation and Leadership in the MENA Region: “It is intriguing that a single word, ‘transformational’ had such an indelible impact on AMAL. It caused all partners, including… Innovation Fund grantees, to look at the familiar words, ‘women’s leadership’ through new lenses, and thus to develop some less familiar ways of encouraging and nurturing women to become leaders in ways that would truly challenge patriarchy and lead to some fresh opportunities for fulfilling women’s rights through advancing their political leadership.”

These are powerful findings. And I know that there are many more examples out there…often underfunded, so often undocumented. I’d love to hear about other examples of work like this.

These are powerful findings. And I know that there are many more examples out there…often underfunded, so often undocumented. I’d love to hear about other examples of work like this.

These alternatives are needed now more than ever for any chance at a fair and sustainable future together on this planet.

The benefits are already proving hard to ignore.

And, increasingly and unapologetically, women from every kind of background, and in every country are coming together, organising, fundraising and strategising together to demand it.

Until then…..we continue, #StillMarching

“We are capable of changing an entire society…. Change is bound to happen….that’s the norm in life”

Young feminist activists, RootsLab Lebanon

February 4, 2018

Links I Liked

There’s research impact, and then there’s social media

Props to the World Bank and Shanta Devarajan for putting together this series of development economics lectures by distinguished academics. Notice anything about the lineup? H/t Alice Evans

Alex De Waal demonstrates how the concept of the ‘political marketplace’ helps explain four enduring puzzles in contemporary Africa and the Greater Middle East.

‘In developing countries for which we have data, about 56% of the kids who are in school are not learning. In sub-Saharan Africa, the number is about 90%’

Just published: The Financial Secrecy Index 2018, the Tax Justice Network’s ranking of secrecy jurisdictions globally

ActBuildChange – promising new website for activists (gives training, support) h/t Alex Sutton

In praise of impurity. Beautiful reflection on the rise of nationalism in Pakistan, UK and everywhere else, from Mohsin Hamid

And just because I like to end with a video, and I’m about to inflict this one on my students, here’s the dancing man with lessons for leadership and how change happens. Enjoy.

February 1, 2018

Campaigning organizations need to do a better job at reaching diverse communities

Guest post from

Foyez Syed

of Save the Children

I went into my local chippie this weekend and got talking to Ahmed, the person serving me behind the counter. I told him I worked at Save the Children as a conflict and humanitarian campaigner. To my surprise he instantly jumped to the humanitarian crisis in Yemen, talking about the blockade in place and the role of the Saudi-led coalition in the crisis. It got me thinking, how do we reach people like Ahmed who’s passionate and knowledgeable about the issues that we campaign on, but wouldn’t come to us?

One of the biggest barriers to reaching Ahmed is the lack of diversity in our workforce in the sector. It means Ahmed is never thought of as a potential supporter. Or if he is, the organisation lacks the ideas, expertise or experience to reach him. In short, the dismal absence of diversity often results in campaigns targeted at the same old audience, with the same old strategy and the same old tactics. Does that sound familiar?

The absence of diversity in our sector is no coincidence. It is a symptom of our society based on the inequality that marginalised people face from birth – institutional discrimination, inherent bias and much more. Then, there is the whole issue of unpaid internships, which means if you can afford to work for free you get a head start. If you’re not from a white middle-class background, you get locked out of the sector.

I’ve experienced this myself. I struggled to get my first job in the sector. Even though I was a serial volunteer, doing everything from campaigning in my own community to being a trustee for a local charity. Even though I ran my own campaign and reached far more people on my own than some charities do. Even though I’ve been on Campaign Bootcamp, a highly thought of programme in the campaigns space. I couldn’t get a break, until Oxfam’s trainee scheme came along.

the best and the brightest

Oxfam’s Campaigns, Policy and Influencing department recognised there was a problem and that’s why they set up a trainee scheme to recruit for diversity. The insights of the trainees from a diverse set of backgrounds unlock the doors to new audiences and lead to more inclusive campaigning. It helps the organisation recognise the structural oppression that exists against marginalised communities. It makes the voice of the organisation more authentic and often more legitimate. Especially if the trainees are from the same background as the organisation’s beneficiaries, as they can then speak from experience and bring a perspective that is so often missed.

Overall, I loved being on the trainee scheme. Admittedly, it was challenging at times going against the grain of the organisation, but I felt it was important for me to do so. Being a trainee provided me with the perfect platform for this. I felt like my opinion was valued. It leaves me better placed to challenge things in my new organisation. I’ve learnt to go about things in a way that is solution focused and shows the value of change to the organisation rather than just voice my frustrations.

Oxfam’s trainee scheme pays living wage and the application stage is blind – just two examples of how the scheme does a great job at addressing the root causes of inequality, but schemes like this are few and far between. Anyone working in the aid sector in the UK will probably have been struck by the overwhelmingly white background of its staff. You only have to take a look round. But that shouldn’t let you stop reaching out to diverse communities and here’s why.

In a recent volunteering role, I helped set up a consultation process where I had to raise several points around diversity and that’s fine. I’m often in the best place to speak about diversity – if I didn’t raise those points I’m not sure if marginalised communities would have been reached during the consultation process. It becomes an issue though, when people become reliant on me always to raise the issue. Why should it always have to be me? Firstly, it’s so draining and secondly why can’t I talk about other issues that I’m passionate about? Why do I have to end up being typecast as the guy who always bangs on about diversity?

That’s where the importance of having allies come in. The sad truth is that when allies speak up it has so much more impact than when I bring the issue of diversity up myself. When it comes from an ‘unusual suspect’ people are more likely to take notice.

I’m very lucky that I sit in a team of allies, so I’m not the only one in my team raising the issue of diversity and talking about how we reach diverse communities. It helps us create more systematic campaigns, campaigns actually addressing the root causes of the issues facing people.

I think it’s time for the sector to be honest with itself and admit it can do much better on reaching out to diverse  audiences. As change makers we are all about making the world a better place. We should all care about diversity as it intersects with all our change goals.

audiences. As change makers we are all about making the world a better place. We should all care about diversity as it intersects with all our change goals.

So here are a few questions to continually ask yourself:

Is diversity the last thing I think about when planning a campaign (if I think about it at all)?

What more can I be doing to reach out to diverse communities?

How do I ensure diversity is considered as an important part of the workplace?

Is diversity the first to go when prioritising time and resources?

Could I be doing more as an ally (whether that’s to my colleagues or ‘beneficiaries’)?

There are many reasons why diversity is important. Not just that is it the right thing to do, but also because it’s the smart thing to do. Not reaching out to the most diverse communities is a missed opportunity to maximise the impact of your campaign.

Next time you’re planning a campaign, ask yourself ‘will Ahmed ever get to hear about this?’ If not, why not?

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers