Duncan Green's Blog, page 102

January 31, 2018

Week One and my students are already exposing my limitations – this is wonderful!

This term, I’m teaching a new course at LSE based on How Change Happens. It’s called ‘Advocacy, Campaigning and  Grassroots activism’. It lasts 11 weeks, and is the first fully fledged university course I’ve taught, complete with lectures, seminars and assessed work (essays, but also blogs and vlogs). So far, I’m loving it.

Grassroots activism’. It lasts 11 weeks, and is the first fully fledged university course I’ve taught, complete with lectures, seminars and assessed work (essays, but also blogs and vlogs). So far, I’m loving it.

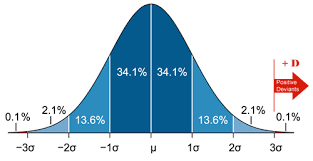

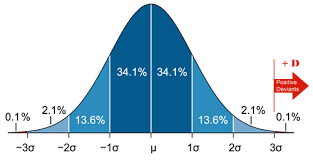

I realized how much fun this could become during the first week of seminar groups (2 x 15 students). Each one hour session is led by groups of students who do the readings and lead the discussion. In week one, the two groups headed off in very different directions and styles. One discussion on Positive Deviance got me particularly interested.

I regularly bang on about Positive Deviance on the blog. It involves identifying and studying the positive outliers on any given issue, to try and understand where the system itself has thrown up solutions to any given problem. Once you’ve identified the reasons behind the outliers, you encourage ‘social learning’ – people in similar situations seeing for themselves, and hopefully changing their behaviours as a result. The Power of Positive Deviance, by Jerry and Monique Sternin, captures both the method and its application to everything from halving malnutrition in Vietnam to FGM in Egypt to tackling superbugs in US hospitals. It’s one of the best books I’ve read in recent years. At a deeper level, PD attracts me as an approach because it respects the system, and is not ‘all about us’ and our projects. I’m even thinking about making it the subject of a future book.

What the students wanted to talk about, though, were the limits to PD, some of which included:

PD is only useful for adaptations within the existing system of power and institutions, rather than challenging the system itself, so if genuine transformation is needed, it may not be up to it (in fitness landscape terms, you might be looking for variations on the same hill, rather than jumping to a different hill)

In fact, isn’t PD in danger of ignoring power and becoming a bit of a technocratic fix?

PD seems to work better for identifying and changing behaviours than for crunchier issues like allocating resources such as land, water or money.

The PD method of identifying outliers + social learning is only relevant to cohesive communities, where positive outliers can be easily replicated.

The interaction between PD and power was particularly interesting. PD works by identifying small positive experiences and scaling them up. But what if the act of scaling tips over from a small variation that can be absorbed by the existing system, and becomes a threat to the powers that be? Would that make the idea of painless scaling a mirage? Is PD a positive-sum or zero-sum game?

The interaction between PD and power was particularly interesting. PD works by identifying small positive experiences and scaling them up. But what if the act of scaling tips over from a small variation that can be absorbed by the existing system, and becomes a threat to the powers that be? Would that make the idea of painless scaling a mirage? Is PD a positive-sum or zero-sum game?

PD also relies on some degree of consensus on what is a positive outlier in the first place, but that does not always exist. One person’s positive outlier (on tax reform, land redistribution, sexuality or access to abortion) can be another’s work of the devil.

And anyway, why was I so keen on PD as an alternative to outside intervention and projects? Was my objection ethical (opposition to/guilt over the White Saviour complex) or practical (outsiders are rubbish at identifying the problems, and even worse at solutions)? Some things, eg vaccination campaigns, should be in the form of external interventions, surely?

Thanks to Youmna Cham, Hussam Zalloum, Carlos Alberto Varela Arias, Katu Cyr, Alev Kayagil and Rashad Nimr for getting us off to such a good start. This term is clearly going to be really interesting!

Hey FP2P readers, can you please help us choose the title for a MOOC on How Change Happens?

We’re in the middle of writing an Oxfam MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) aimed at activists around the world.  It brings together some of the themes of How Change Happens (Power and Systems) with some of Oxfam’s more practical internal training materials for campaigners. More on the content to follow, but right now we have to decide on a title in the next day or two, so my mind went back to the crowdsourcing of the cover for HCH, which worked like a dream. So here’s your task: Choose one of these titles, or suggest a better one in the comments (polite options only, please):

It brings together some of the themes of How Change Happens (Power and Systems) with some of Oxfam’s more practical internal training materials for campaigners. More on the content to follow, but right now we have to decide on a title in the next day or two, so my mind went back to the crowdsourcing of the cover for HCH, which worked like a dream. So here’s your task: Choose one of these titles, or suggest a better one in the comments (polite options only, please):

Note: There is a poll embedded within this post, please visit the site to participate in this post's poll.

Please vote now!

January 30, 2018

My (current) default suggestions when asked about almost anything to do with ‘strategy’

I realised recently that I have a fairly standard playlist of topics I bang on about to people during the frequent ‘blue  sky’ (well, the initials are BS, anyway) sessions after someone phones up and says something like ‘can I pick your brains as part of our strategy refresh?’ So I thought, if I am going to give the same answers whatever the questions, I could save everyone a lot of time by writing them down in one place. Also, I’m getting a bit bored listening to myself (hate to think how other people feel).

sky’ (well, the initials are BS, anyway) sessions after someone phones up and says something like ‘can I pick your brains as part of our strategy refresh?’ So I thought, if I am going to give the same answers whatever the questions, I could save everyone a lot of time by writing them down in one place. Also, I’m getting a bit bored listening to myself (hate to think how other people feel).

So here’s my playlist, with links

Systems Thinking and Ways of Working

Writing How Change Happens threw up some recurring issues about the way we think and work:

Shocks and Critical Junctures: Change in complex systems occurs in slow, steady processes such as demographic shifts, punctuated by sudden, unforeseeable jumps. These discontinuities are often linked to crises, shocks and scandals: the status quo is thrown up in the air, and when it returns to earth, things have changed. That stop–start rhythm can confound aid agency plans and processes. The one bit of the aid business that is designed for such a rhythm is the humanitarian/emergencies bit – the rest of us need to learn from them about how to identify, analyse and respond to critical junctures and the opportunities and threats they create.

Adaptive Management, Doing Development Differently and Alternatives to the Logframe: Traditional aid projects often resemble baking a cake; a neat, linear process of ingredients + recipe → result. Reality is much messier in complex systems such as polities, societies and economies: prediction is a fool’s errand; attribution elusive; we are navigating in a fog. That means setting up systems to get fast feedback, and to respond to that fast feedback through ‘adaptive management’.

Positive Deviance: this involves identifying and studying the positive outliers on any given issue, to try and understand where the system itself has thrown up solutions to any given problem (child malnutrition, school drop-out rates etc). It attracts me as an approach because it respects the system, and is not ‘all about us’ and our projects. So why isn’t it a standard entry point when we are considering a new area of work?

Positive Deviance: this involves identifying and studying the positive outliers on any given issue, to try and understand where the system itself has thrown up solutions to any given problem (child malnutrition, school drop-out rates etc). It attracts me as an approach because it respects the system, and is not ‘all about us’ and our projects. So why isn’t it a standard entry point when we are considering a new area of work?

Getting to the Grassroots

Immersions: Nothing like spending a week in a village for jolting aid wallahs out of their assumptions and arrogance. Why don’t more organizations make it obligatory?

Diaries: Portfolios of the Poor is a wonderful book that explored how 250 poor families managed their finances by sending the same researchers back every two weeks to talk to them, building trust and uncovering a previously invisible financial ecosystem. If we are serious about understanding how poor people live, allocate their time, resolve their problems etc, why don’t we learn from that and do diaries on governance, environment, health etc etc, before jumping in with our idea of what is needed? We’re currently trying it out on governance in Mozambique, Pakistan and Myanmar as part of our ‘Action for Empowerment and Accountability’ research programme.

Who we work with: Unusual Suspects

Beyond the state/CSO mindset: Missing out crucial ‘non state actors’ like faith organizations, traditional leaders, informal civil society networks (eg cultural associations, savings groups or funeral societies, women’s networks) seriously undermines our ability to understand how power and influence operate in any society.

Supporting individuals/leadership (inc Universities): we need new ideas for identifying and supporting progressive leaders, whether at the grassroots or further up the food chain. We could even revamp some old ideas, like scholarships. We also lack a clear universities’ influencing strategy where we identify and target next generation leaders by university, department or role (eg student union leaders), influencing them via curricula, lectures, immersions or internships.

Grey Panthers: why do we equate campaigning with young people, when retired folk have time, contacts and experience? More broadly, we need to think harder about the life cycle of activism.

Spin offs and seeding the system: You can’t turn a supertanker like Oxfam into a scrappy, innovative, experimental start up, so why don’t we deliberately spin off a bunch of our projects with a bit of funding every year, to seed the ecosystem with new ideas and approaches?

What we work on

From the Exotic to the Familiar – the end of the ‘development issue’. Why aren’t tobacco, alcohol or road traffic core development issues? After all, they all kill many more people in poor countries than, say, malaria.

development issues? After all, they all kill many more people in poor countries than, say, malaria.

The world is urbanizing; effective social movements are more likely to emerge from shanty towns than rural villages, so why do many INGOs find it so hard to go urban?

My Rules of Thumb

Beyond specific suggestions, I have a set of heuristics – ways I screen the conversation. These include:

Do you have an explicit power analysis or theory of change about what you are trying to achieve? If not, why not?

Have you thought about gender? What about other aspects of exclusion/inequality?

Can you point to successful examples of what you are proposing? Conversely, if your suggested has never worked, anywhere, maybe you should think about why that is!

What mechanisms do you have in place to identify what you are doing wrong, and change course?

So now, if people still insist on BS sessions, I can at least save some time by sending them this post in advance, and saying this is where we will begin the conversation.

But what have I missed?

January 29, 2018

When is eradicating a major disease a disaster for healthcare?

Guest post from Laura Kerr, Senior Policy Advocacy Officer (Child Health), RESULTS UK

Guest post from Laura Kerr, Senior Policy Advocacy Officer (Child Health), RESULTS UK

The world is on the brink of a historic breakthrough – the eradication of polio. Cause for celebration, right? Well yes, in terms of getting rid of a killer disease, but because of the way the aid business has distorted health systems around the developing world, the end of polio could tip many countries into a health disaster.

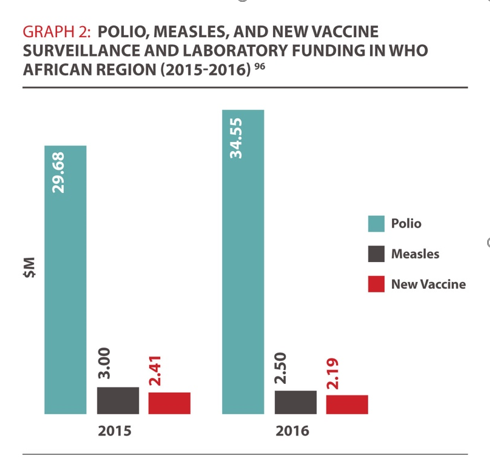

The fight against polio has mobilised big bucks for over 30 years, polio funding has been used by the poorest countries around the world to support critical aspects of their health systems, such as health workers and disease surveillance, to the tune of around $1billion a year. The Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) is one of the world’s largest health partnerships and planned spending by the GPEI will halve between 2017 and 2019 – a reduction of over $300million in 3 years. What happens now as polio money disappears and who is responsible for filling the gaps which will be left?

Since donors have ultimately created a situation where health systems have become reliant on polio funding, what can they do now to prevent these systems collapsing? Do we need a new vertical financing mechanism or streams to fill gaps which will most certainly be left? After years of a narrow disease eradication approach, now is the time to have a frank conversation about how the donor community can better support health systems in a sustainable way.

This is the subject of our new report, in A Balancing Act: risks and opportunities as polio and its funding ends which looks at what needs to happen now if the victory over polio is not to be overshadowed by a looming health crisis that can be averted.

But what are the gaps and why are we so worried? A few examples include:

70% of global funding for disease surveillance comes from GPEI. An area which is already underfunded, there is an existing need for increased investment.

40% of all WHO staff who work in the African region are funded through GPEI. Most will work on a whole range of health issues beyond polio.

702 GPEI funded staff in South Sudan are the backbone of the health service. Spending only 27% of their time exclusively on polio eradication, the rest of their time they deliver routine immunisation and basic health services.

Graph from A Balancing Act highlighting comparable funding for polio surveillance compared to other vaccines preventable diseases.

Addressing these (and many other) gaps exposes the fundamental challenge of shifting disease specific eradication efforts in global health towards a systematic approach that builds and finances strong health systems which are able to provide health services to all of those who need them. We do not need another disease specific fund or initiative.

However, the problem we face is that donors prefer to fund things which are easier to track numerically – children immunised and lives saves is much easier to document a return on investment on compared to the long-term impact of training of health workers or improvements to disease surveillance or the cold chain. What makes sense for the donor often does not make sense for developing countries and their inhabitants.

Continuing with the same “business as usual” approach, with donors filling disease specific funding gaps, will do nothing but stick a plaster over existing gaps in health systems. This is unsustainable, especially in the context of other global health donors who are also beginning to transition away from certain countries (see quick analysis of this here). Worryingly, there is limited acknowledgement of the scale of the gaps which will exist, what comes next, or a desire to tackle the wider issue of sustainable financing for health systems.

When over 20% of WHO’s budget and 35% of UNICEF’s immunisation staff supported through GPEI, there are some serious structural barriers that need to be addressed. This poses a serious conflict of interest that could lead GPEI partners to shy away from a frank and honest conversation about the future financing of global health.

As things stand now, the potential crisis caused by the wind down of GPEI is not fully realised. This limits the ability of the global health community to have the much-needed frank conversation about what comes next after GPEI. Without leadership from the five GPEI partners to realistically address the imminent challenges which are currently presenting themselves, we’re walking straight into a preventable health financing crisis and it’s the most vulnerable in the world which will be left suffering.

And for more on Oxfam’s policy work on health, visit the Global Health Check blog

And for more on Oxfam’s policy work on health, visit the Global Health Check blog

January 28, 2018

Links I Liked

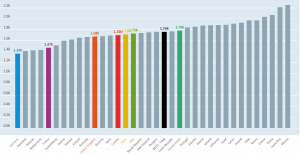

So much for stereotypes: Mexicans work the longest hours in the OECD, Germans the least. (click to expand)

So much for stereotypes: Mexicans work the longest hours in the OECD, Germans the least. (click to expand)

Freedom of Information requests reveal that the UK Government (Foreign Office and Department for International Trade) are still championing the interests of British American Tobacco. Reminder. Smoking kills 6m people a year, mostly in poor countries (WHO figures). A genuine scandal.

Charles Kenny v Angus Deaton on whether US charity should begin at home (Deaton thinks more US aid should be redirected to domestic poverty spending)

Some non-Oxfam Davos analysis:

Is Davos ‘ a form of moral self-licensing. Once you’ve convinced yourself that you’re the good guy, you can go on to behave appallingly’?

Is Davos ‘ a form of moral self-licensing. Once you’ve convinced yourself that you’re the good guy, you can go on to behave appallingly’?

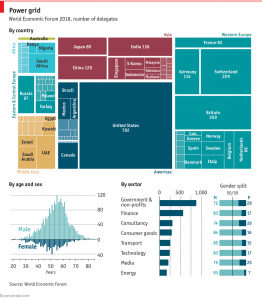

Breakdown of Davos delegates by country, gender, sector, via The Economist. What’s with Luxembourg? (click to expand)

Why Don’t Poor Farmers Move to the City? Excellent survey of the evidence by Justin Sandefur

‘Development blogging is definitely in a crisis’. I’m too close to the topic to be objective – do you agree?

US air wars under Trump: increasingly indiscriminate, increasingly opaque.

5 Challenges to Work on Social Accountability in Fragile, Conflict and Violent Settings. Excellent 5m video summary from Anu Joshi of IDS

January 25, 2018

Book Review: ‘I’ve got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle’ Charles M Payne

I’ve given my kids a lot of improving books over the years, and now they’re exacting revenge. Parental devotion  means I read anything they give me, which at least gets me out of the aid and development ghetto. My Christmas present this year from son Calum was Charles Payne’s wonderful book on the US civil rights movement, which also kept me sane during a grim, cold, sunless holiday failing to see the Northern Lights in Norway.

means I read anything they give me, which at least gets me out of the aid and development ghetto. My Christmas present this year from son Calum was Charles Payne’s wonderful book on the US civil rights movement, which also kept me sane during a grim, cold, sunless holiday failing to see the Northern Lights in Norway.

Payne seems to have interviewed just about everyone from the civil rights movement in the Mississippi Delta (the book was first published in 1995) and sets out in huge detail the evolution of the movement from the end of World War Two to the late 60s. He uses that analysis to challenge conventional narratives and shed real light on a marvellous moment in US history.

First the myths. As one high school student put it, ‘One day, a nice old lady, Rosa Parks, sat down on a bus and got arrested. The next day Martin Luther King Jr stood up, and the Montgomery bus boycott followed. Sometime later, King delivered his famous ‘I have a dream’ speech and segregation was over.’

Some of the things airbrushed out of the narrative: Parks had been a civil rights activist since 1943. Months before her protest in December 1955, Parks had attended leadership training at the Highlander Folk School. An organized group of 300 educated Black women led by English professor Jo Ann Robinson had been agitating on desegregation since 1946. When Parks sat down in December 1955, Robinson’s group had already considered and discounted 3 other protests that year for various tactical reasons. This time they gave the green light and had a rock solid boycott in place within 3 days of Parks’ protest.

As for the churches, MLK may be a hero, but the civil rights movement also faced a lot of resistance from other, more conservative preachers. Nothing is as it seems.

Now for the lessons – insights and wisdom are plentiful, and far too numerous for a blogpost, but here are some that jumped out for me:

Leadership: I’m still looking for a really good sociological analysis of which kinds of people become grassroots leaders and why (do let me know if you have any suggestions). This book has some good observations: leaders often had knowledge of the wider world, whether from fighting in World War Two or travelling, or a degree of economic independence. Faith played a huge role, both in motivating people to take action, and in shaping the way they approached activism. Middle class businesspeople, preachers and teachers tended to keep their heads down in the first, most dangerous years, but often supported the movement behind the scenes. Finally, leadership clustered around families rather than individuals – the same names crop up, as activist parents raise up activist children.

Rosa Parks on the bus

Two further characteristics that Payne identifies is that many of the core organizers were women, often airbrushed out of the history because of the conventional focus on preachers and violence (although some of the women organizers packed a good punch, literally). A chapter is devoted to describing and celebrating the work of extraordinary figures like Ella Baker and ‘Mrs Hamer’. When Mrs Hamer stood up to speak during a mass meeting that was going badly (hot; boring speeches):

‘Immediately, an electric atmosphere suffused the entire church. Men and women alike began to stand up, call out her name, urge her on’. She described the moral evil of racism ‘with a kind of redemptive reconciliation, a vision of justice that embraced everyone. She ended by leading the assembly in chorus after chorus of the old spiritual, ‘this Little Light of Mine’. When she finished, people crowded round her to promise they would join the struggle.’

The second is ‘slow and respectful work.’ Organizers took time to get to know and understand local people and culture. They listened. One local organizer who Payne clearly venerates is Bob Moses. When asked how you organize a town, he replied ‘By bouncing a ball. You stand on a street corner and bounce a ball. Soon all the children come around. You keep on bouncing the ball. Before long, it runs under someone’s porch and then you meet the adults.’

Payne charts the power of the movement’s bottom-up approach. ‘In the very act of working for the impersonal cause of racial freedom, a man experiences, almost like grace, a large measure of private freedom. Call it a new comprehension of his own identity, an intuition of the expanding boundaries of his self, which, if not the same thing as freedom, is its radical source.’

But by the mid-60s, that commitment to slow and respectful work, built by bringing on local leaders and getting out

Ella Baker

the way, gave way to the more strident, divisive tone of Black Power. Payne shows that this was not just about Black activists preferring separatism, but turning their backs on Ella Baker’s organizing tradition of finding a place even for ‘Black ladies in minks’ in the movement. Purism and ideological disputes took over from that ‘slow and respectful work’ and deep engagement with the people of the Delt. But ‘you cannot organize people you do not respect’.

Was that inevitable? I have seen it recur often enough to think it might be. Partial victories (and they are always partial) trigger division between reformers and radicals; disillusionment sets in when promises are not kept; success changes the incentives – less selfless, more careerist people get involved; engagement with conventional politics is both a sign of victory, and the start of the moral rot.

I have run out of space, yet barely started. Buy it for your kids (or your parents). And please tell me what else to read on the roots of leadership.

January 24, 2018

Tackling poverty and injustice by influencing behaviours and practices: what works?

Ruth Mayne, Oxfam’s senior researcher on influencing, introduces a new discussion paper on behaviour and practice change, written with Melanie Kesmaecker-Wissing, Lucy Knight and Jola Miziniak. This was first posted on Oxfam’s Views and Voices site.

change, written with Melanie Kesmaecker-Wissing, Lucy Knight and Jola Miziniak. This was first posted on Oxfam’s Views and Voices site.

Behaviour change strategies can play a vital role in combating poverty, injustice and environmental problems, whether by helping end gender-based violence, improving health and hygiene behaviours, reducing resource-intensive consumption patterns or helping mobilise people to take action.

But do we really understand how to achieve behaviour and practice change? Our new discussion paper seeks to enhance the design of change strategies by drawing on learning from theory and practice. It focuses mainly on deep-seated and habitual gender, WASH (“Water, Sanitation and Hygiene), health, and environmental behaviours, but also contains insights for policy influencing, public mobilisation and consumer behaviours. It outlines:

The range of influences that can shape people’s behaviours at individual, group, societal and system levels;

The associated change interventions that can be used to address them with illustrative practical case studies.

The key steps necessary for planning and designing behavioural change interventions

Individual influences

Some economic theory assumes that people are rational, self-interested and autonomous, influenced mainly by their internal decision making processes. This approach emphasises the role of information and financial incentives in influencing people’s choices. Both play a useful role, but tend to have modest impacts on habitual or deep seated behaviours due to the range of other influences shaping them.

ANITA WITH HER TWO CHILDREN IN TEMPORARY SHELTER, NEPAL SEPTEMBER 2015. CREDIT: SAM TARLING/OXFAM

In contrast to this narrow view of human behaviour, psychological and behavioural theories show that people often act in unconscious, irrational, altruistic and cooperative ways and take mental ‘shortcuts’ – unconscious habits, values, frames, emotions and personal agency. Mothers’ emotions about nurturing their children were, for example, found to be a powerful motivator for promoting handwashing with soap in an Oxfam project in Nepal.

Therefore, to be effective change interventions also need to carefully frame narratives and information, strengthen agency and/or use prompts and environmental cues to ‘nudge’ people towards better habits. For example, a big breakthrough for the gay marriage campaign in the US occurred when it shifted the framing of its messaging from equal rights to love and commitment.

Interpersonal and group influences

Socio-psychological and social learning theory highlights that people are social beings and therefore strongly influenced by their perceptions of and interactions with other people, particularly peers or role models, as well as by groups and institutions. Evidence shows that group interactive action and learning activities are effective ways of changing behaviours, as they create safe informal spaces where people can pioneer, model and learn new behaviours with others. Global Action Plan’s Eco teams are one example, but similar approaches have also been used in gender and WASH. Even just simply communicating that other people are behaving in certain ways – social norm appeals – can be powerful. One experiment increased the recycling rates of hotel towels by adding a message to their signs saying that most other guests recycled.

Structural influences

But addressing individual and group influences can only achieve so much. There may also be structural constraints affecting people’s behaviours, such as power relations (including vested interests), government policy, cultural or religious beliefs, infrastructures or services. Improving public health or hygiene behaviours, for example, depends in part on people’s access to safe water, adequate sanitation, health services and medicines.

A South African health campaign, LoveLife, realised that HIV/AIDs among youth was driven more by

From the Lovelife site

disenfranchisement due to high unemployment, gender inequality and low self-esteem, than by any lack of awareness of health risks. It successfully increased youth use of condoms and reduced the number of their sexual partners by involving them in health, education and employment programmes, along with festivals, sports and other recreational activities.

Contributing to wider system change

There is some evidence that multi-pronged and multi-level strategies are most effective at addressing deep seated and routine behaviours. Some Oxfam country programmes, for example, use a combination of influencing tactics to tackle violence against women and girls, which may include a mix of: changing attitudes and beliefs and social norms; supporting women’s rights organizations; changing government policies and practice; empowering women economically; and/or enabling access to support services.

While few CSOs are able to carry out multi-pronged/level interventions on their own, they can help contribute to widespread behaviour change by (a) modelling and spreading new behaviours and behaviour change strategies to others and/or (b) influencing other actors – such as governments and faith institutions – to adopt, support, promote and complement them, including when appropriate with legislation.

Alternatively, CSOs can identify and tackle key system influences. For example, the ‘Cool Biz’ campaign – introduced in Japan in the summer of 2005 –reduced the use of office air conditioning, and hence carbon emissions, by changing clothing customs rather than via individually focused environmental awareness raising. The campaign got government staff, including the prime minister, to model a new casual dress code at work. As the dress code didn’t involve a suit or tie offices were able to turn down the air conditioning, hence lowering carbon emissions.

If you have experience of behavioural and practice strategies that have and haven’t worked we’d love to hear from you in the comments section below. Also, look out for more posts in this blog series on influencing.

January 23, 2018

From Dandora to Davos – organising from the grassroots and puncturing the elite

With the inequality crisis in focus as the world’s elite gathers in Davos, the Fight Inequality Alliance

’s Global  Convenor, Jenny Ricks (@jenny_ricks )

, examines where real change is likely to come from

Convenor, Jenny Ricks (@jenny_ricks )

, examines where real change is likely to come from

Inequality, and sage words about needing to tackle it, are once again ringing through the halls of Davos. As a counterpoint to this, we in the Fight Inequality Alliance are holding our global week of action calling for an ‘End to the Age of Greed’. So it’s as good a time as any to assess where we are in the fight against inequality. Let me offer a couple of thoughts.

There’s reasons to be cheerful over how far the agenda has come: Policy demands galore – check. Eye watering stats – check. Business and political elites name checking the issue regularly – check. Sustainable development goal – check. This is all progress (and a recognition of how serious this is from a number of perspectives) and a familiar trajectory for many campaigns. However, it’s clear that we’ve won the debate, but not the fight.

Davos remains gloriously hypocritical on inequality. The contrast between the concerned words and the (in)action (none or negative) has been well skewered by economist Branko Milanovic, while the over-optimism of elites on an economic ‘recovery’ has been revealed by Guardian Economics editor Larry Elliott, so I’ll spare you the repeat. This will not self correct. The arguments are obvious – and we know it is ridiculous to keep looking to Davos for the answers. Turkeys and Christmas?

“It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” Upton Sinclair

This is now the fifth year in a row of ‘Oxfam’s annual Davos stat day’ (it’s a Thing, go with it) – it does a great job of crystallising for us the depth of the mess we’re in, in a way I can talk to anyone about quickly, and providing a wedge into what sits beneath – the wider, systemic and intersectional problem. [And it is very important that we understand inequality beyond just wealth and income – patriarchy, racism, neoliberalism, exploitation etc give inequality long, deep and mutually reinforcing roots across the world. And people have experienced and long organised against existing inequalities of race, caste, gender, disability, sexual orientation or identity, class and ethnicity – this informs how we organise and respond.] But stats only take us so far. And for people living on the frontlines of inequality across the world, change is in short supply.

So where is the change coming from? Wrestle your eyes away from the acres of media coverage and social media scrolling that Oxfam’s media team must be basking in this week. It’s hard to do, but let’s stick with it for a few minutes.

Inequality is at heart an issue of power. We (including Oxfam), founded the Fight Inequality Alliance because we  knew that change comes when People Power becomes stronger than those driving and benefitting from the status quo. The policy prescriptions that would do the most to ensure societies that work for all are largely known and already campaigned on by many. Women’s rights groups, social movements, young people, trade unions, environmental groups, NGOs, have all been tackling aspects of the inequality agenda for a long time in their struggles for a just and equitable world. But given the intense concentration of power and wealth in so few hands across the globe, the dangerous sweep of right wing extremism, sexism, austerity, misogyny and discrimination, accompanied by a crackdown on democratic rights and freedoms, these struggles needed to join up and build collective power on a larger scale. So this is what we are focussing on – those on the frontlines of inequality organising from below and across borders to shift the balance of power to create the just, equal and sustainable world we’re all fighting for. Key to this is more organising and collective action, led by women, young people, social movements.

knew that change comes when People Power becomes stronger than those driving and benefitting from the status quo. The policy prescriptions that would do the most to ensure societies that work for all are largely known and already campaigned on by many. Women’s rights groups, social movements, young people, trade unions, environmental groups, NGOs, have all been tackling aspects of the inequality agenda for a long time in their struggles for a just and equitable world. But given the intense concentration of power and wealth in so few hands across the globe, the dangerous sweep of right wing extremism, sexism, austerity, misogyny and discrimination, accompanied by a crackdown on democratic rights and freedoms, these struggles needed to join up and build collective power on a larger scale. So this is what we are focussing on – those on the frontlines of inequality organising from below and across borders to shift the balance of power to create the just, equal and sustainable world we’re all fighting for. Key to this is more organising and collective action, led by women, young people, social movements.

Which leads me to Dandora. This week has seen lots of interest in an event the Kenya chapter of the Alliance are organising in Dandora, a giant rubbish dump in Nairobi, and home to large numbers of its poorest residents. It tells the story from the ‘other’ mountain, and the realities of the local ‘experts’ there who live the inequality referred to in Davos, day in and day out. See the video below from ‘the other mountain’ in Dandora, with Ashura Mciteka & Nelson Munyiri on why ordinary people are uniting to #fightinequality :“We have billionaires on the #Davos mountain talking about issues that are affecting people like us on the garbage mountain.” she says. The end of the week of action will play host to the #UsawaKenya festival (Equal Kenya) there, headlined by hip hop artist and Dandora resident Juliani. Journalists have been interested in this story. It feels new and fresh.

Which leads me to Dandora. This week has seen lots of interest in an event the Kenya chapter of the Alliance are organising in Dandora, a giant rubbish dump in Nairobi, and home to large numbers of its poorest residents. It tells the story from the ‘other’ mountain, and the realities of the local ‘experts’ there who live the inequality referred to in Davos, day in and day out. See the video below from ‘the other mountain’ in Dandora, with Ashura Mciteka & Nelson Munyiri on why ordinary people are uniting to #fightinequality :“We have billionaires on the #Davos mountain talking about issues that are affecting people like us on the garbage mountain.” she says. The end of the week of action will play host to the #UsawaKenya festival (Equal Kenya) there, headlined by hip hop artist and Dandora resident Juliani. Journalists have been interested in this story. It feels new and fresh.

Why? Because the problem of inequality is known by all and lived daily by the many. The grotesqueness (is this a word?) of the current levels of wealth are unsustainable and morally repugnant. But this must lead to change – a new system will be born, but it will be citizens that drive it. They are tired of the same conversations. On some level, people recognize instinctively that the status quo is wrong, but have felt that we are lacking solutions, as Martin Luther King warned us. Partly we have been looking in the wrong place for answers. It’s time to listen to the people who know the most about inequality.

And it’s not just Kenya. Protests happening around the world this week, from Mexico to South Africa to Tanzania to Indonesia to Vietnam to Denmark and many beyond.

There’s an appetite to hear the counter story. This is a good start, and a journey we’ll continue on over the coming years.

The fight against inequality is well under way. But change will be fought from the grassroots and connected to the national and global, not the other way round. Adjust your gaze.

January 22, 2018

Links I Liked

10 years on from the start of the financial crisis, macroeconomics still hasn’t come up with a big new idea in response to the last decade of crisis. Robert Skidelsky brilliantly takes issue with Paul Krugman, arguing that meant Neo-Keynesianism only lasted 6 months after the 2008 crash, and then it was back to austerity-as-usual.

Tunisia is back on a knife edge – here’s why. Reads like a structural adjustment story from 1980s Latin America. Democratization + IMF-led austerity → disillusionment and instability.

Is there an analytically meaningful distinction between ideas and interests? Brilliant brainfood from Dani Rodrik, with a follow up conversation between him and Peter Hall.

Go on, cheer yourselves up for a (brief) moment. In a world where many things appear to be going backwards, we have made incredible progress on one anti-corruption policy.

Last copy of the board game ‘Suffragetto’ (based on Monopoly) to go on display at Oxford, marking the centenary of when women over the age of 30 won the right to vote in the UK. Time for a new edition?

Last copy of the board game ‘Suffragetto’ (based on Monopoly) to go on display at Oxford, marking the centenary of when women over the age of 30 won the right to vote in the UK. Time for a new edition?

And some Sausagefestgate Fallout:

Calling all lecturers/students: upload the gender breakdown of your course reading lists in this table from Alice Evans (a lecturer in Development Studies at Kings College) and me. Once we get a critical mass of entries, it could become a really useful resource and commitment device.

Gender discrimination in political science and the problem of poor allies. Excellent and thought-provoking h/t Rakesh Rajani

‘Economics has an insidious bias against women’ says The Economist in a research-packed long read.

Great Davos video. “We have billionaires on the Davos mountain talking about issues that are affecting people like us on the garbage mountain.” A message from the other mountain – Ashura Mciteka & Nelson Munyiri on why ordinary people are uniting to fight inequality. And thanks to #fightinequality for responding to my request to put it up on youtube (after 15.000 hits on twitter) so I could embed it here:

January 21, 2018

Davos is here again, so it’s time for Oxfam’s new report on prosperity and poverty, wealth and work.

As the masters of the universe (or at least planet earth) gather in Davos, here’s a curtain-raiser from  Deborah Hardoon, Oxfam’s Deputy Head of Research, introducing its new report.

Deborah Hardoon, Oxfam’s Deputy Head of Research, introducing its new report.

Gotta love a data release. Every year I look forward to the release of the Credit Suisse Global Wealth databook. An immense piece of work, developed over a decade and led by Anthony Shorrocks, which brings together all available data on household wealth within countries all over the world. It tells us how much wealth there is, and where it is. This year, by incorporating historical data sets too, we can better understand how the household wealth distribution has been changing over time.

The dataset gives us some pretty startling headline findings.

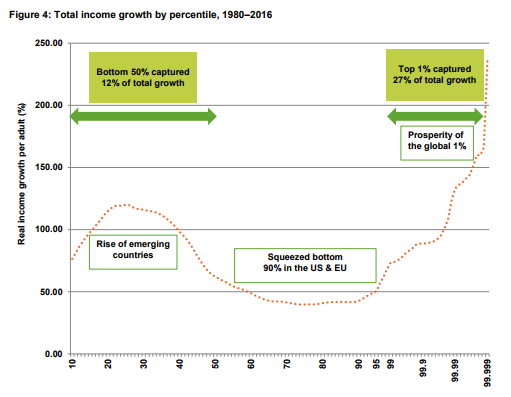

Global net wealth continues to grow. Since 2000 net wealth has increased by approximately $114 trillion in real terms, to a whopping $280 trillion.

US wealth dwarfs that of any other country, standing at $93 trillion. Chinese wealth has increased by more than 300% over this period to $29 trillion, making it the second wealthiest country in the world. In Africa, where there are 200million more people than China, total wealth stands at just $2.5tr.

The richest 1% in the world have more wealth than everyone else put together.

Total wealth increased by more than $9 trillion between 2016 to 2017, of which 82% went straight to the richest 1%. The bottom 50% saw no increase in net wealth over this period.

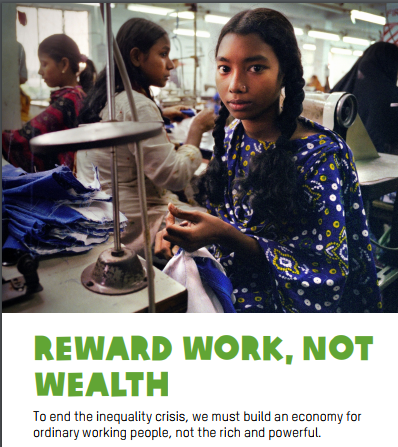

Oxfam’s report ‘Reward work not wealth’, out today, looks at these statistics and analyses what this means for people. It headlines on this last bullet point: last year, for every $5 of wealth created, $4 went to the already wealthy. So what does this look like for different people around the world?

Oxfam’s report ‘Reward work not wealth’, out today, looks at these statistics and analyses what this means for people. It headlines on this last bullet point: last year, for every $5 of wealth created, $4 went to the already wealthy. So what does this look like for different people around the world?

Well, the wealthy have been doing rather well. Billionaires in particular, 90% of whom are male and many of whom will be gathering at Davos this week, will be happy to have seen their wealth accumulate off the back of ‘an epic year for stocks’. As the economy grows, wealthy asset owners have been receiving an ever-increasing slice of this pie, as measured by the trend of the increasing capital (declining labour) share of GDP. Other evidence suggests that monopoly power and inheritance help keep the wealthy in good times. Many of these billionaires will be shaking each others’ Rolex-flanked hands in the mountains of Davos this week and discussing the very economy that has helped them sustain and grow their nest eggs.

What about the bottom 50%? The bottom 50% saw no increase in net wealth in the last year. None. For many, hard work is not proving to be the ticket to prosperity. In developing countries the number of people working but in poverty is now on the rise. Precarious and low paid work, unpaid care work and discriminatory and abusive workplaces are the norm for hundreds of millions of people around the world. Women face multiple barriers, being paid less than men, more likely to experience violence in the work place and more likely to be responsible for unpaid care responsibilities. In unpacking wage inequalities and shining a light on the working poor, through telling personal stories of exploitation, [such as that of Dolores, who works in a chicken factory in the US but wears a nappy because she is unable to take sufficient toilet breaks], the report paints a very different picture of the state of the economy and how people are rewarded for their contribution.

because she is unable to take sufficient toilet breaks], the report paints a very different picture of the state of the economy and how people are rewarded for their contribution.

Even as we celebrate the ongoing decline in extreme poverty around the world, it’s also clear that the global economy could do far better for people living in poverty and particularly for working women. So the report asks the reader, which will hopefully include those people gathering in Davos, to consider an alternative. What if there were rules in place that meant that companies couldn’t pay out enormous CEO salaries and dividends to shareholders until all their employees were paid a living wage? What if alternative business models were incentivised, which give workers an ownership stake in the company and/or a say in the way it operates and distributes rewards? What if poverty wages were eliminated, with minimum wages set at a level that allows a decent standard of living and an end to discriminatory practices, allowing working families to save and invest. What if extreme wealth could be effectively taxed, ending the holidays and havens enjoyed by the wealthiest. And what if the revenue was used to invest in health and education, cutting down the barriers people face in trying to escape poverty?

And here’s the infographic

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers