Duncan Green's Blog, page 106

November 23, 2017

Links I Liked

Don’t forget to take the FP2P Readers Survey. Only takes 5 minutes, honest, and there’s prizes…..

Being poor often means living with constant shame. Efforts to mitigate poverty must recognize the importance of self-respect – or risk perpetuating the problem they seek to solve. Excellent from Keetie Roelen at IDS

‘An unconditional cash transfer was found to reduce the odds of having any illness by an estimated 27%.’ Evidence v the Daily Mail, round 342

I have a new paper out, published by IDS. I promise you that ‘Theories of Change for Promoting Empowerment and Accountability in Fragile and Conflict-Affected Settings’ is more interesting than it sounds……

Policymakers do not need impact evaluations as much as they need other kinds of research/analysis. Excellent insights from Latin American Evidence Week

Businesses are increasingly reporting on the SDGs. [h/t Alice Evans]

So farewell then Robert Mugabe, and a good time to remember the memorably weird Nandos Ad

November 22, 2017

Kevin Watkins on the power of stigma and shame as a driver of change

Kevin Watkins, a fellow Prof in Practice at the LSE, came along to talk to my students last week (review by Masters student Haisley Wert here). Kevin is a bit of a  research and campaigning legend in the aid biz – the brains behind a lot of epic Oxfam campaigns on trade and debt in the early noughties, he went on to write some of UNDP’s best Human Development Reports (on Climate Change, Water and Aid, Trade and Security), galvanized UNESCO’s Education for All Global Monitoring Report and then ODI and most recently moved across to run Save the Children UK.

research and campaigning legend in the aid biz – the brains behind a lot of epic Oxfam campaigns on trade and debt in the early noughties, he went on to write some of UNDP’s best Human Development Reports (on Climate Change, Water and Aid, Trade and Security), galvanized UNESCO’s Education for All Global Monitoring Report and then ODI and most recently moved across to run Save the Children UK.

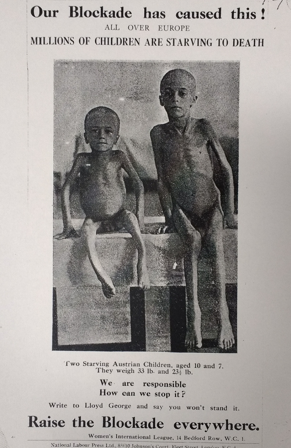

His topic was children, armed conflict and impunity, and what caught my attention was his emphasis on the importance of shame as a driver of change. He went back to the campaign to abolish slavery, SCF’s founder Eglantyne Jebb’s fight against the blockade of Europe after World War One (Kev showed some period poverty porn – but in 1919 the starving kids were Austrian), and the campaign against US use of napalm against children in Vietnam, to argue that invoking stigma and shame is one of the most effective ways to bring about change.

Austria 1919

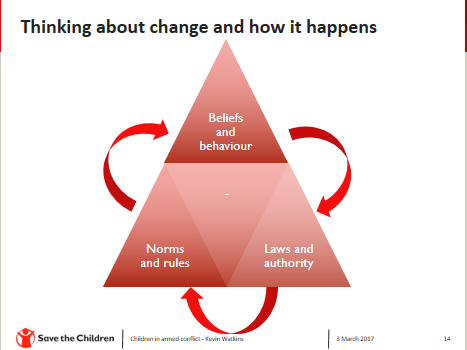

Kevin talked of the job of campaigners as ‘restoring the proper sense of moral opprobrium’ over the abuse of children during conflicts, and sees the link between norms/rules and behaviour as mutually reinforcing. He also believes that international rules do exert some kind of traction on leaders – ‘Even President Assad feels compelled to report to the UN on violations of child rights. There is a power in normative documents and processes.’

But he later clarified ‘stigma alone is not a powerful vehicle for change. It has to be linked to a practical and achievable strategy for change that enables people to make a difference.

The reason I’m interested in stigma and shame is that they are closely related to the internalisation of norms that shape how people behave – far more powerfully so than hard law.’

His key reference was The Honor Code, by the brilliant British-born Ghanaian-American philosopher Kwame Appiah. According to the excellent review by the Guardian:

‘Appiah discusses four different historical episodes. In three of them moral revolutions took place, and in the fourth another may be brewing. They are: the demise of duelling in England in the early 19th century; the end of the centuries-old, agonising practice of foot-binding for women in China at the beginning of the 20th century; the abolition of slavery in the British empire; and finally the barbaric treatment of women in much of Pakistan today. These revolutions did not come about as a result of specifically moral argument. The moral arguments against duelling, foot-binding, slavery and disfigurement and execution of innocent women were known long before they influenced public attitudes. And when they did so, it was not because of any intrinsic appeal to rationality, or even humanity or sympathy. Rather, a shift had to occur in which people began to feel that their honour was compromised by the practice. Reformers had to mobilise contempt and shame, the sense of being dishonoured even by belonging to a society in which such things took place.’

I read The Honor Code while researching How Change Happens, but for some reason, did not reference it. That feels  like a mistake – the focus on norms, and the link to shame, seems really valuable, in particular in what you could call ‘moral high ground campaigns’ on subjects like violence against children or slavery. Maybe I’ve got too caught up in the evidence-based wonkery and ‘economism’ of some modern-day campaigning, where you spend all the time talking about effectiveness, return on investment and results, and forget there are such things as good and evil, which often make for a much more powerful narrative, for both public and decision makers, than a load of regressions or survey results.

like a mistake – the focus on norms, and the link to shame, seems really valuable, in particular in what you could call ‘moral high ground campaigns’ on subjects like violence against children or slavery. Maybe I’ve got too caught up in the evidence-based wonkery and ‘economism’ of some modern-day campaigning, where you spend all the time talking about effectiveness, return on investment and results, and forget there are such things as good and evil, which often make for a much more powerful narrative, for both public and decision makers, than a load of regressions or survey results.

Not that good and evil are unproblematic of course. Back in the 1990s, while researching Hidden Lives, a book for Save on child rights in Latin America, the book that had the biggest impact on me was Philippe Aries’ ‘Centuries of Childhood’, which chronicles the social construction of the modern day view of childhood as a private ‘walled garden’. Part of that construction is that adults tend to have a polarized view of children as either ‘Oliver Twist’ – innocents in danger of corruption by adults, or ‘Lord of the Flies’ – little savages in need of socialization. Kevin’s narrative seems heavily weighted towards the former, which raises some tricky questions we didn’t have time to go into, such as at what point does children’s increasing agency as they grow older (as established in the Convention on the Rights of the Child) also mean that they become responsible for their actions and cease to be Oliver Twist? Students raised this in the context of child soldiers: Kevin seemed inclined to stick with Oliver Twist by saying circumstances (eg lack of job opportunities) were forcing kids to do bad things. True, but an argument with limits I think.

Huge thanks to Kevin, who I had to drag away from the students after 2.5 hours on a Friday afternoon!

November 21, 2017

What are the politics of our survival as a species? Introducing the Climate Change Trilemma

So a physicist, an anthropologist, and two political economists have lunch in the LSE canteen and start arguing about climate change…..

climate change…..

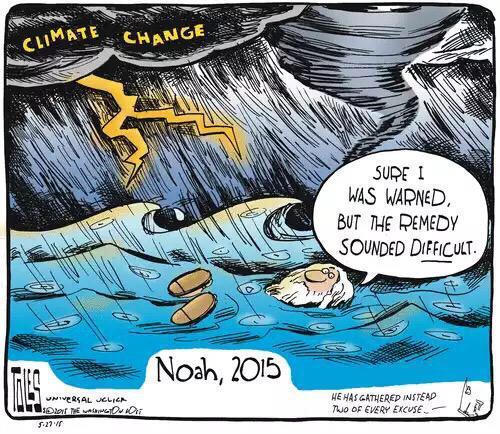

I was (very notionally) the physicist; my other lunchtime companions were Robert Wade, Teddy Brett and Jason Hickel (the anthropologist). Jason was arguing for degrowth and reminded me of the excellent debate on this blog a couple of years ago between Kate Raworth and Giorgos Kallis; I responded by asking him (as I do) ‘where’s your theory of change?’ It boils down to this: what future paths are feasible, when science appears to be incompatible with politics? Here are four scenarios (I’m sure there are more):

Optimist: The world listens to the science and the scientists and somehow finds a way to stay within the planetary boundaries (decarbonization, broader shift to sustainability, including shift in norms around consumption etc)

Pessimist: Can’t be done in any system short of an absolute dictatorship (see my earlier conversation with Tim Jackson on this) – we’re going to fry or drown, or both.

Political Realist: Can’t be done and is going to get very nasty. Sea level rises, mass displacement, a tide of chaos which may bring back Scheidel’s four horsemen. Millions will have to die and suffer before a political path to sustainability can be found.

Technophile: Relax guys, we’ve got this. Some combination of renewables, geoengineering, dematerialization of production etc can bail out our dysfunctional politics in time to avert a meltdown.

Jason’s point is that we are between a rock and a hard place. The science is absolute, as are the planetary boundaries. He argues that there is no evidence for the technophile escape and that ‘in a real democracy’ (i.e one magically not distorted by power and inequality) we can jointly agree a way out. The politics may be difficult, but it has to be more malleable than science.

Jason’s point is that we are between a rock and a hard place. The science is absolute, as are the planetary boundaries. He argues that there is no evidence for the technophile escape and that ‘in a real democracy’ (i.e one magically not distorted by power and inequality) we can jointly agree a way out. The politics may be difficult, but it has to be more malleable than science.

I want to believe him, but fear the political realist scenario is more likely, hopefully eased by a dash of technological breakthrough. I don’t think capitalism is compatible with de-growth and neither is democracy, at least not as currently constituted. Companies compete on the basis of price and productivity. That means producing more stuff in most cases. Whatever the well-justified criticisms of GDP as a measure of wellbeing, Governments don’t get elected when the economy is shrinking.

So de-growth has to be predicated on some alternative to capitalism, and has lots of ideas about what such an alternative could look like, but no convincing theory of change for how it might actually come about, politically. Lots of ‘If I Ruled the World’ grand plans, hand waving and cries of ‘have you got a better idea?’ (to which the answer is usually no, but that doesn’t constitute an answer).

Globally it feels like we may have a trilemma: take 1. Capitalism (which to date has proved the most successful system, at least in some variants, in terms of ending poverty and expanding their freedoms to be and to do, Amartya Sen style); 2. Democracy and 3. Environmental Sustainability: you can have 2 out of 3 but you can’t have all of them:

Capitalism + Democracy without Sustainability: the current model

Capitalism + Sustainability without Democracy: Tim Jackson/China (maybe)

His checklist of what needs to happen to is extraordinarily long and sounds like a political equivalent of the economist ‘assume a can opener’ joke: in an exchange on the first draft of this post, he spelt out ‘restoring the commons. So, decommoditize healthcare and education and housing; get rid of the fractional reserve banking system, set up a positive money system (or 100% reserve banking), abolish GDP as a measure of progress and as a political objective, redistribute existing resources to take pressure off growth, change shareholder value rules; think a basic income.’ Only then will the trilemma be solved. But what are the politics of achieving any/all of these?

Can anyone lighten my gloom?

Jason is also having an argument with Branko Milanovic along these lines. Branko isn’t impressed: ‘If put to test in real life, rather than at conferences and blogs, Jason’s program would receive support from almost no one.’

And if you find this a worthwhile topic, are anywhere near London, and want to hear a top writer and thinker tell me where I’ve got it all wrong, come along to hear Kate Raworth debate Doughnut Economics with LSE Economist Oriana Bandiera tomorrow (Thursday 23rd). I’ll be chairing, so will have to bite my tongue.

November 20, 2017

Do you have to be cold to be cool? Canada joins the Nordics as a world leader on rights.

I was in Canada last week, having a lot of fun on a speaking tour with Oxfam Canada, followed by a couple of days with Oxfam Quebec in

Shirley Pryce, Julie Delahanty and some bloke, on tour

Montreal. One of the striking impressions is how much Canada’s foreign policy rhetoric echoes that of the Nordics in its focus on rights (an even more striking impression was that minus 20 degrees centigrade is really not much fun).

We visited what, as far as I (and Google) can work out, is the world’s only Human Rights Museum, a beautiful piece of architecture stuffed full of thought-provoking exhibits. Trouble is it’s in Winnipeg, which even other Canadians say is in the middle of nowhere. Maybe it could set up Virtual Reality rooms in museums elsewhere so people could take a tour without actually going there?

On the tour I discussed how change happens and women’s rights with Shirley Pryce, a self-described ‘energy bunny’ who set up the Jamaica Household Workers’ Union, and Oxfam Canada boss and influential feminist , plus great local activists in each of the 5 cities we visited.

First, indigenous rights. What rapidly became clear was that Canada is living through a painful period of introspection about its treatment of its native peoples. A court case brought by some of the estimated 150,000 people removed from their families as kids and sent to grim Residential Schools (the last one closed in 1996) led to a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, whose report in 2015 has galvanized the whole debate.

Second, women’s rights. In June 2017, Marie-Claude Bibeau, Minister of International Development and La Francophonie, launched Canada’s new Feminist International Assistance Policy (FIAP), echoing Sweden’s Feminist Foreign Policy. The FIAP focuses on six areas:

Gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls

Human dignity

Growth that works for everyone

Environment and climate action

Inclusive governance

Peace and security

I asked various people about the roots of ‘Canadian exceptionalism’ on FIAP, and got some useful insights:

History: in past decades, Canada has had a strong, government-funded women’s movement, led by National Action Committee on the Status of Women, some notably strong women in government such as Foreign Minister Flora MacDonald in the 1980s, and has played an active role at a diplomatic level on UN conventions such as CEDAW. More broadly, Canadian John P. Humphrey was one of the drafters of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, while Prime Minister Lester B Pearson is recognized as ‘the father of modern peacekeeping’.

History: in past decades, Canada has had a strong, government-funded women’s movement, led by National Action Committee on the Status of Women, some notably strong women in government such as Foreign Minister Flora MacDonald in the 1980s, and has played an active role at a diplomatic level on UN conventions such as CEDAW. More broadly, Canadian John P. Humphrey was one of the drafters of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, while Prime Minister Lester B Pearson is recognized as ‘the father of modern peacekeeping’.

Under the widely criticised previous administration of Stephen Harper ‘gender’ was more or less excised from government vocabulary, in favour of a more traditional focus on women as mothers, entrepreneurs or victims. That thinking led to significant funding for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (MCNH) programmes, though without any attention paid to sexual and reproductive health and rights. And in fact, little spent on the M part of the equation.

After winning the 2015 election, the new government led by Justin Trudeau wanted to put daylight between itself and Harper, and gender equality was one of the options. Trudeau and his wife Sophie Gregoire are both pro-choice feminists. The rapturous response both inside Canada and beyond to initial steps such as insisting on a 50% female cabinet and Trudeau’s speech at UN Women confirmed that this was a rich symbolic battlefield. Hence the FIAP.

So what happens next? I was struck by a level of defeatism among some of the people I spoke to – ‘in 18 months this will be gone’  prophesied one academic and former aid official. Cynics cite the lack of new money accompanying the announcement – it’s all style and no substance.

prophesied one academic and former aid official. Cynics cite the lack of new money accompanying the announcement – it’s all style and no substance.

But it seems more promising than that. The Harper Administration tied up a lot of aid spending in advance of the new government, and as that runs out, the new grants are being subject to close scrutiny and new policies. The government committed C$650m on Women’s Reproductive Health Rights (a much welcomed response to Donald Trump’s move in the opposite direction) and additional money to support women’s rights organizations. The Minister’s office is also reportedly sending back funding proposals that are not focused on gender equality and women’s rights.

But if there is to be more than a short-term spending spree, activists need to think about how the FIAP can be ‘locked in’ even when the political tide turns against Trudeau-style feminism. There may be some useful lessons from two contrasting and comparable initiatives in the UK: Labour’s much trumpeted 1997 ‘Ethical Foreign Policy’ bit the dust after a couple of scandals and disappeared without trace; in contrast, its commitment to spending 0.7% of national income on aid ended up becoming bipartisan and enshrined in national law. Which of these contrasting fates awaits FIAP?

So far, the biggest impact of the new policy has probably been symbolic – unashamedly using (and celebrating) the F word. That has shaken up more conservative thinkers (including among the NGOs, judging by my conversations!). A next step is to start turning that into not just policy, but institutional reality. Julie Delahanty recommends putting more resources into the endeavour and explicitly hiring feminists that also have the technical skills needed – ‘stop hiring people because they are good at agriculture or education and then expect them to apply feminist principles’. It might also mean finding new partners that adhere to feminist principles

As well as changing the people and the policies, lock-in would be helped by overhauling the institutional plumbing – effectively, sticking the word ‘feminist’ in front of the nuts and bolts in the aid organigram of human resources, procurement, monitoring and evaluation etc, then brainstorming on what that might look like. Oxfam Canada, which made women’s rights its main focus over a decade ago, is now talking to the government on a lot of this agenda. Beyond aid, what would feminist mining policy look like? A Feminist NAFTA renegotiation, anyone?

Another symbolic battleground could be Canada’s 2008 ODA Accountability Act. Its current text does not explicitly mention feminism or gender equality. Amending it might send further good signals and (slightly) raise the cost of any future backsliding.

Other ideas?

November 19, 2017

Dear readers, please tell us what you think about the blog (there’s prizes)

How time passes when you’re having fun, or at least shooting your mouth off. It has come to our attention that we haven’t asked your opinion on anything very much for over five years now (see here for summary of last survey in 2012). So some technologically gifted people in Oxfam have put together the reader survey. I would really appreciate you clicking on it – we’re due an upgrade, so it’s an ideal time to make any necessary tweaks to improve the blog. Go on, two minutes of your time once every five years isn’t that much to ask. And to make it fun, we’ll give 10 free paperback copies of How Change Happens, with the winners chosen at random.

Take the reader survey. It runs til 18th December, so I can spend Christmas brooding over the responses. Not really.

And please ignore Calvin – he is a bad person

November 15, 2017

To Uber or not to Uber? That is Your Question

OK, I’m probably going to regret this but… should I use Uber taxis? I got into a big argument about this in Canada last week, not that  there was a uniform position – Ellie the Oxfam Canada campaigner sees Uber as the spawn of the devil, while Ifthia the fund raiser has an Uber-driver Dad. When I randomly asked a class of students, I got a 10:1 vote in favour of Uber.

there was a uniform position – Ellie the Oxfam Canada campaigner sees Uber as the spawn of the devil, while Ifthia the fund raiser has an Uber-driver Dad. When I randomly asked a class of students, I got a 10:1 vote in favour of Uber.

So I got to reflecting on how we go about deciding whether something like Uber is good or bad, and what it says about how activists approach a new and disruptive technology.

First, let’s be clear, Uber is disruptive and causes some damage. London cabbies who have spent years doing ‘the Knowledge’ suddenly find that a combination of GPS and Uber have made all that effort redundant. Minicab firms are being undercut, potentially triggering a race to the bottom in terms of fares and working hours. Where there are unionised taxi companies (as in some Canadian cities) they risk being undermined. There is understandably a lot of bad feeling out there among drivers, leading to worldwide protests and the occasional brawl or worse.

But there’s more to it than that.

Winners or Losers? Capitalism is all about creative destruction, but activists typically want the creation without the other bit. Faced with a disruptive technology, we are always worried about the people whose livelihoods are being destroyed, reasonably enough, but what about the ones being created? Would we have campaigned for horse and cart drivers and opposed the introduction of the motor car?

What counts? I have talked to dozens of Uber drivers and other cab drivers in several countries, and am struck by the way the conversations generally focus on things other than money. Uber drivers usually praise the flexibility of choosing their hours, the security of knowing who the clients are and (in the vomit-prone UK) knowing that if some drunk throws up in your car, you will not have to frogmarch them to a cashpoint and risk a fight. Instead Uber deducts the cost of cleaning up the car from the vomiter’s credit card and sends them an email with the subject line ‘oops!’. Nice touch. Non Uber drivers tend to focus on the lack of training, alleged security risks etc, rather than the undeniable fact that Uber is undercutting their business.

Producers v Consumers: There are some curious asymmetries here. I think we often tend to focus on producer (dis)satisfaction – are drivers better/worse off. But we pay very little attention to consumers. The contrast for me of taking Ubers and traditional yellow cabs in New York was startling – friendly, interesting chats in Uber cabs v sullen, occasionally hostile Yellow Cab drivers. Plus the Uber drivers knew how to get to my destination, thanks to GPS, whereas Yellow Cab drivers seemed to think that was my responsibility. And of course, Uber is usua lly a lot cheaper, which brings in a whole swathe of new consumers like students or parents who use it for their kids, safe in the knowledge that they can track their movements.

lly a lot cheaper, which brings in a whole swathe of new consumers like students or parents who use it for their kids, safe in the knowledge that they can track their movements.

What happens next? There is a backlash against Uber in many cities, including London. That is probably a good thing. I have a feeling that this will lead to a process of domestication/regulation, rather than prohibition. Already the house-training of Uber has seen the departure of its savage-capitalist founder Travis Kalanick. Competition from ‘ethical uber’ companies like Lyft has forced Uber to introduce tipping for drivers (and in the opposite direction, competition from Uber has forced cab companies to introduce many of its features, such as sending you the name and number plate of your driver in advance). We’ll see a tightening up of Uber’s security checks and other processes. A key question will be whether it is required to treat its drivers as employees – good news from the London courts last week on this.

If Uber is tamed, its fares are bound to rise, but I have no idea by how much – will it lose its competitive edge? Personally, I would probably use it even if it cost the same as other cabs, for a whole host of reasons (interesting, engaged drivers, convenience, and I like watching the swarms of little cars on my phone, driving around on the street map….), but I may be unrepresentative.

One other thing which strikes me. I’ve been surprised how few women Uber drivers I’ve had (I can only think of one, in Washington). You

Anti-Uber protests

would think that the flexibility in hours and traceability of passengers would work for women, and maybe now Mr Macho has departed, Uber could help turn around its reputation by offering a Pink Uber with women drivers for women passengers, along the lines of the Pink Taxi movement in many cities.

Anyway, I realize that this is a massively one-sided account of the arguments for/against, so do get stuck in in the comments section, and here’s a longer, perhaps more even-handed long read from The Walrus. And now I turn it over to you to comment and vote.

Note: There is a poll embedded within this post, please visit the site to participate in this post's poll.

November 14, 2017

What’s so bad with Business as Usual on Livelihoods? Impressions from Eastern Congo

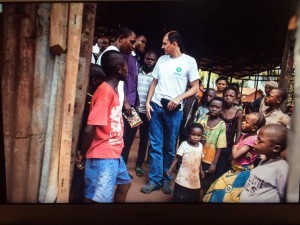

Our country director in DRC, Jose Barahona (right), sent round some interesting impressions from a recent visit to the Eastern Congo.

South Kivu in Eastern Congo is one of the most beautiful landscapes in Africa and I am convinced that one day this area will be one of the world’s top tourist destinations. The day DRC is calm and stable, the millions of tourists fed up with queuing for hours at the Sagrada Familia, walking through herds of people in Venice, or having to book a year in advance to walk around in Yosemite…. They will come here.

I was visiting a programme funded by DFID that combines livelihoods and protection, an idea that came out of the brilliant mind of Joanna Trevor (Programmes Manager in DRC at the time of designing the project). The livelihoods component is pretty much business as usual: we identify cooperatives, provide them advice to increase productivity, improved seeds, better ways to sale their products… etc. The place was here:

The members of the cooperative I visited today were indeed quite happy with this way of working: they have better seeds for onions; they are able to grow two crops of onions a year (quite an achievement since an onion plant takes six months from seed to harvest); they have a larger, heavier onion. They also have a place to store them and they send someone to Bukavu to negotiate the price and sell a whole truck of onions each time. Before our intervention, they had worse seeds that gave them a smaller (lighter) onion, one crop per year and each farmer would sell at a very low price to the first intermediary passing by. Yes, I recognize this is not innovative, but… it works! We worked out the numbers together with the farmers and they calculated that now with two crops per year, heavier onions and better prices, they are making three times the money they were making three years ago. Not bad!

The members of the cooperative I visited today were indeed quite happy with this way of working: they have better seeds for onions; they are able to grow two crops of onions a year (quite an achievement since an onion plant takes six months from seed to harvest); they have a larger, heavier onion. They also have a place to store them and they send someone to Bukavu to negotiate the price and sell a whole truck of onions each time. Before our intervention, they had worse seeds that gave them a smaller (lighter) onion, one crop per year and each farmer would sell at a very low price to the first intermediary passing by. Yes, I recognize this is not innovative, but… it works! We worked out the numbers together with the farmers and they calculated that now with two crops per year, heavier onions and better prices, they are making three times the money they were making three years ago. Not bad!

I know we are expected to ‘innovate to achieve impact at scale’. I know we should increase our advocacy, supporting these cooperatives to work together with other similar coops across Congo to put pressure on the Congolese Government to implement the Maputo declaration to spend at least 10% of the budget in agriculture…. But hey! Supporting cooperatives in the traditional way, when properly done, works and people are happy with it.

I love to spend time walking across fields, talking with proud farmers, everything green and growing around us. Smell the wet soil; the

Jose with Oxfam boss Mark Goldring

mountains on the horizon… I can’t deny I enjoy it more than when I visit our latrines in crowded camps to check if our system against bad smell really works… and confirm that sometimes it doesn’t.

Other impressions from the visit:

Corruption: The protection group explained that in the roads around the area there are eight army checkpoints. Everyone passing is forced to pay US$0.80 each time they pass through a checkpoint. If they have to pass a couple of these, a farmer going from home to their field and back ends up paying US$3.20 a day. Farmers can’t afford that kind of drain, so the protection group negotiated with the army and now there are “only” four check points and they “only” have to pay US$0.30 each time they cross one. Sometimes we say the Congolese state has no presence, but it is not true. It does have a presence but is always to extract money from people, never to provide services.

Bullets found this Sunday in the Oxfam office in Bukavu

The risks of working in Congo: On Sunday morning there was an incident in a house close to our office in Bukavu. It ended up with 8 hours of shooting involving Kalashnikovs and heavy artillery. Our colleagues spent the whole morning laying on the floor. By the end, several bullets had entered our office. This reminded me how volatile situations are in areas where there are so many guns, how much our colleagues working in conflict zones risk every day.

November 13, 2017

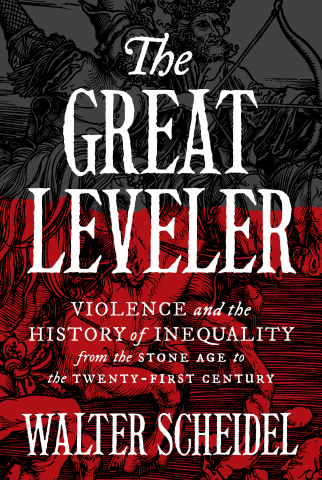

The Great Leveller: A conversation with Walter Scheidel on Inequality and Apocalypse

When I visited Stanford recently at the invitation of Francis Fukuyama, I also dropped in on Walter Scheidel, an Austrian historian who  has taken time off from his main interest (the Romans) to write a powerful, and pretty depressing, book on inequality.

has taken time off from his main interest (the Romans) to write a powerful, and pretty depressing, book on inequality.

Like Fukuyama, Scheidel is a big brain who favours the grand narrative – his book is called ‘The Great Leveller: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the 21st Century’. Its argument is:

‘For thousands of years, history has alternated between long stretches of rising or high and stable inequality interspersed with violence compressions. For six or seven decades from 1914 to the 1970s or 1980s, both the world’s rich economies and those countries who had fallen to communist regimes experienced some of the most intense levelling in recorded history.’

He identifies four sources of compression – the ‘Four Horsemen’: ‘mass mobilization warfare, transformative revolution, state failure and lethal pandemics’.

‘Just like their biblical counterparts, they went forth to ‘take peace from the earth’ and ‘kill with sword, and with hunger, and with death, and with the beasts of the earth.’ Sometimes acting individually and sometimes in concert with one another, they produced outcomes that to contemporaries often seemed nothing short of apocalyptic. Hundreds of millions perished in their wake. And by the time the dust had settled the gap between the haves and have nots had shrunk, sometimes dramatically.’

In this, Scheidel echoes Piketty’s account of the equalizing impact of two world wars, but whereas Piketty then turns to policy-based ways to reduce inequality, such as a wealth tax, Scheidel sees history as much more of a straitjacket. He argues that ‘the traditional violent levellers currently lie dormant and are unlikely to return in the foreseeable future. No similarly potent alternative mechanisms of equalization have emerged… There does not seem to be an easy way to vote, regulate, or teach our way to significantly greater equality.’

Not only that, but he sees new trends exacerbating inequality, including ageing, immigration, automation and the remaking of the human body into the ‘GenRich and the Naturals’, in the words of Princeton geneticist Lee Silver.

He summarizes the policy proposals of would-be Levellers (a group which includes Oxfam). On the revenue side these include (his list is more exhaustive – see p432):

‘Income should be taxed in a progressive manner. Wealth should be taxed directly and in ways designed to curtail its transmission across generations. Sanctions would prevent offshore tax evasion. Corporations should be taxed on their global profits. Public policy should boost intergenerational mobility by equalizing access to and the quality of schooling.

On the expenditure side, public policies should provide forms of insurance. Universal health care would buffer against shocks. More ambitious schemes include a basic minimum income. Business regulation would include changing laws regarding patents, antitrust, and contracts. Institutional reforms should revive union power, raise minimum wages, improve access to employment for underrepresented groups.’

A good list, right? Trouble is, Scheidel concludes that meaningful levels of redistribution require such huge changes to, for example, tax rates, that the politics don’t stack up, and laments that there is ‘surprisingly little interest in how to turn such proposals into reality.’

Drivers of Change?

He concludes that ‘policy making can take us only so far’ because the kinds of policies that would make a difference occur only in times of crisis – i.e. they need the four horsemen to reappear, but ‘the Four Horsemen have dismounted their steeds. And nobody in his or her right mind would want them to get back on.’

Why? Because taking them in turn

Mass mobilization warfare: ruled out both because the increasing lethality of technology means that wars will now either be terminal for the species, or more confined – the kind of levelling of World Wars One and Two is no longer possible.

Transformative Revolution: Post-Communism, no sign of that kind of huge upheaval and destruction

State failure and systems collapse is now more confined to the low and middle income countries, and so will not affect global inequality levels

Severe epidemics: there’s always the risk of new disease creating a global plague, but the speed and sophistication of the medical response makes this unlikely.

His conclusion?

‘Much of the world has entered what could become the next long stretch – a return to persistent capital accumulation and income concentration. If history is anything to go by, peaceful reform may well prove unequal to the growing challenge ahead.’

When we met, I said I liked the book, but felt honour bound to push back: firstly, we’ve seen lots of developing countries in Latin America and elsewhere reducing inequality in recent decades, so while his grand sweep, helicopter view of history may be important, particularly when it comes to inequality in the US and Europe, it is clearly not the last word.

Second I asked him whether climate change could become a fifth horseman. He says this always comes up when he presents the book, and agreed that yes, unless checked, runaway climate change could indeed cause all four horsemen to remount, but that would be a pretty thin silver lining, given the apocalypse that would ensue.

I love history when it provides hope and the oxygen of new ideas and alternatives. Alas, Scheidel’s version of history seems to do the exact opposite, sucking hope and oxygen out of the important discussion on tackling inequality. Anybody else read it and have views?

November 12, 2017

Links I Liked

Huge thanks to everyone at Oxfam Canada, its Executive Director me dance onto the stage to Bob Marley’s ‘Stand up for your Rights’, get up at 4am in minus 20 degrees and wear OTT shirts.

Burundi ordered all unwed couples to marry by the end of the year, or else. Welcome back WTF Friday

Crisis modifiers: the way to a more flexible development-humanitarian system? Smart thinking from the ODI.

One for the diary if you’re in or near London. I’m chairing Kate Raworth and Oriana Bandiera  discussing Doughnut Economics, at LSE on 23rd November. No advance registration required, but get there early for a good seat.

discussing Doughnut Economics, at LSE on 23rd November. No advance registration required, but get there early for a good seat.

This is totally enchanting – treat yourself to (12m)

‘Economists who let their enthusiasm for free markets run wild are not being true to their own discipline’. Vintage Dani Rodrik

Looking for a visual metaphor for tax dodging, after the Paradise Papers? Sorted

November 9, 2017

Sociology v Economics: handy translation guide

Some more academic humour to add to the recent ‘what researchers say v what they mean‘ post, (gets better as you go down the table) via Chris Blattman. From a 1990 ‘Economics to Sociology Phrasebook‘ by two baffled economics students. It shows its age, but wears well, which is as much as any of us can aspire to.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers