Duncan Green's Blog, page 108

October 25, 2017

How can NGOs get better at using evidence to influence governments and companies?

This week I attended an ‘Evidence for Influencing’ conference in the Netherlands. A couple of Oxfam colleagues had  started planning it as a small event, and then found such interest in the topic that it mushroomed to 150 people over 2 days, roughly divided between Oxfammers and others (NGOs, media, academia).

started planning it as a small event, and then found such interest in the topic that it mushroomed to 150 people over 2 days, roughly divided between Oxfammers and others (NGOs, media, academia).

My overall impression was that campaigners, academics and governments are all struggling with the link between evidence and influencing. It’s a bit like teenage sex – everyone thinks that everyone else is doing it with great expertise and having a fine old time, and that it’s just you that has no idea what you’re doing…..

I had to give some broad comments, many of them drawing on previous posts on this blog. Sorry if that means you’ve heard them before, but as I recently told UNICEF bloggers, a powerpoint is just a blog waiting to be written, so I thought I’d follow my own advice. Anyway, according to Fidel Castro ‘repetition is a revolutionary virtue’.

First point, what do we mean by evidence? The organizers defined it as ‘data or information presented in support of an assertion’. So research at the ‘hard’ end of the spectrum (lots of data, RCTs and the rest) is just one form of evidence: experiences (whether of researchers, or of communities and individuals) are another, as are narratives. The plural of ‘anecdote’ may not be ‘data’, as Claire Melamed says, but it is certainly evidence.

Which kinds of evidence should NGOs be stressing? Over recent decades, we have moved from relying almost entirely on moral suasion (we call it ‘framing’ these days) with stories, but little data to back it up (‘we have a moral duty to help poor countries’) to today’s blend of morality and measurement. Overall, that has to be a good thing, but if the measurement people become too professionalized and insulated from the rest of their organizations, there are downsides too: they risk becoming delinked from the thinking about power, politics and influence and start to believe in the power of ‘pure’ research, with some panels at the conference starting to resemble the ritualised academic dance of hypothesis, methodology, findings. (Don’t get me started on panels)

Which kinds of evidence should NGOs be stressing? Over recent decades, we have moved from relying almost entirely on moral suasion (we call it ‘framing’ these days) with stories, but little data to back it up (‘we have a moral duty to help poor countries’) to today’s blend of morality and measurement. Overall, that has to be a good thing, but if the measurement people become too professionalized and insulated from the rest of their organizations, there are downsides too: they risk becoming delinked from the thinking about power, politics and influence and start to believe in the power of ‘pure’ research, with some panels at the conference starting to resemble the ritualised academic dance of hypothesis, methodology, findings. (Don’t get me started on panels)

That worries me because if NGOs start to behave like traditional academics they could disappear from view, eclipsed by the sheer scale of academia. A recent paper found that there are 200,000 full time academics in the UK alone. In contrast, the full time equivalents of Oxfam’s researchers on issues of development, poverty etc number less than 100 world-wide. So we need to spot the niches we can usefully fill – the over-used ‘USP’ (Unique Selling Point) of marketing.

For me the USP of aid NGOs comes down to authenticity, connectedness and being able to produce clear, convincing narratives and powerful, human stories. For all sorts of reasons, academia often fails miserably at one or more of these. So the kind of evidence we generate should build on our USP: work extra hard to find, test and polish powerful narratives and/or make what we say is rooted solidly in the experience of our programmes or the lives of real people; give far more attention to ‘bearing witness’ – ensuring that the voice of people, communities, local leaders and organizations, and even our own frontline staff acquires greater, less mediated prominence in the way we talk to the public. This would be a challenge to NGO people keen to ensure a single, coherent message goes out to the public, but it could really help shift the balance of power in who shapes the conversation about development issues. Anyone fancy setting up an NGO to do this – maybe a ‘Hear Directly’ to sit alongside ‘Give Directly’?

narratives and powerful, human stories. For all sorts of reasons, academia often fails miserably at one or more of these. So the kind of evidence we generate should build on our USP: work extra hard to find, test and polish powerful narratives and/or make what we say is rooted solidly in the experience of our programmes or the lives of real people; give far more attention to ‘bearing witness’ – ensuring that the voice of people, communities, local leaders and organizations, and even our own frontline staff acquires greater, less mediated prominence in the way we talk to the public. This would be a challenge to NGO people keen to ensure a single, coherent message goes out to the public, but it could really help shift the balance of power in who shapes the conversation about development issues. Anyone fancy setting up an NGO to do this – maybe a ‘Hear Directly’ to sit alongside ‘Give Directly’?

That attention to reality on the ground also reflects a shift to systems thinking – we should spot the positive deviants that the system has already thrown up and help to record, understand and spread them; run diary projects to uncover the real lives of poor communities; behave more like anthropologists investigating what is actually happening out there in all its messy glory, rather than economists seeking to confirm their ‘priors’; escape from the tyranny of the project and ‘it’s all about us’.

Part of ‘dancing with the system’ is spotting and responding to the windows of opportunity offered by crises and failures of public policy. Academics struggle to respond to such ‘critical junctures’, perhaps due to being trapped by the conveyor belt of journal papers and research programmes. But to be honest, NGOs often aren’t much better.

The importance of timing goes beyond crises-as-opportunities. Political timetables are more open to evidence and influence at some moments than at others (new leaders, manifestoes and elections as well as after scandals); as issues travel down the ‘policy funnel’ from public discussion to state action, they require different kinds of research at each stage; people as individuals are more open to evidence at some times than at others (when they are young, or in an unfamiliar context or new job).

How can we get better at spotting impending or current opportunities and rapidly marshalling the evidence that is needed? One way is to get away from one of the greatest barriers to ‘evidence for influence’ – the dead hand of supply side thinking. Research conferences are all about the supply of research – the panels, the tenure cattle market etc. There is precious little attention given to the demand side, when do the people we are trying to influence actually want to hear new evidence? In what form? (even with government ministers, first-hand experience usually trumps any number of academic papers). Who do they want to hear about it from (the messenger, not the message)?

How can we get better at spotting impending or current opportunities and rapidly marshalling the evidence that is needed? One way is to get away from one of the greatest barriers to ‘evidence for influence’ – the dead hand of supply side thinking. Research conferences are all about the supply of research – the panels, the tenure cattle market etc. There is precious little attention given to the demand side, when do the people we are trying to influence actually want to hear new evidence? In what form? (even with government ministers, first-hand experience usually trumps any number of academic papers). Who do they want to hear about it from (the messenger, not the message)?

Bridging supply and demand is all about building networks and relationships, not just plans and products, as Babu Rahman explained so brilliantly recently. Evidence doesn’t speak or influence for itself. Researchers can’t hide behind their desks; they have to get out more (and not just to talk to other researchers).

Others who attended the conference, feel free to add your bit.

October 24, 2017

Should we boycott gated journals on social media? How about a pledge?

It’s International Open Access Week, so this seems a good time to post on something that’s been bugging me. I had a slightly tetchy exchange on twitter recently with someone (who wishes to remain anonymous) who sent me a

It’s International Open Access Week, so this seems a good time to post on something that’s been bugging me. I had a slightly tetchy exchange on twitter recently with someone (who wishes to remain anonymous) who sent me a link to their paper and asked me to circulate it if I liked it. Problem was the link was to a journal, where you had to pay to read. I could read it for free if I really wanted to, thanks to my LSE job (universities subscribe to all the big journals), but it’s still a hassle, and anyway, that’s not really the point – I hate the elitism of gated journals, so why link to them? The would-be self publicist replied that for a young academic, there’s no option, and then various other people weighed in (twitter’s fun like that).

link to their paper and asked me to circulate it if I liked it. Problem was the link was to a journal, where you had to pay to read. I could read it for free if I really wanted to, thanks to my LSE job (universities subscribe to all the big journals), but it’s still a hassle, and anyway, that’s not really the point – I hate the elitism of gated journals, so why link to them? The would-be self publicist replied that for a young academic, there’s no option, and then various other people weighed in (twitter’s fun like that).

If you’re in an NGO that doesn’t have a subscription, the paperwork to reclaim your $20 for buying a paper online is likely to put you off altogether. The broader consequence is that academia retreats inside it’s self referential, peer-reviewed, paywalled filter bubble, and the rest of the world remains largely oblivious, deepening the gulf between the universities and the practitioners. Not good for either camp, I would argue.

Net result, I think I now have a personal policy of not linking to gated journal articles on twitter or in the blog, but should I go further and set up a sign-up pledge for other social media users, as Owen Barder has done so laudably on manels (1296 currently signed up)?

Arguments for:

Keep up the pressure for Open Access, which is making significant progress, even if it is prompting journals to now demand that authors pay to publish their articles (see this brilliant long read on how Robert Maxwell established the journal model for superprofits).

Push authors to publish drafts on ResearchGate, blog their findings, and otherwise try and cater to the mass of humanity that languishes outside Academia and the paywall.

Encourage people to use Sci Hub as an alternative way to find content (I checked and sure enough, the original article that prompted the exchange is on there for free, as is my bête noire, the ODI’s unacceptably gated Development Policy Review (note, no link!), but are all development-related journals up there?).

Dance on Robert Maxwell’s grave (there’s a queue, so you need to plan ahead)

Arguments against/complicating factors:

Arguments against/complicating factors:

Apparently health and education journals won’t publish your article if you have put up the data elsewhere, eg on ResearchGate

Some tricky grey areas – eg gated newspapers like the FT and the Economist. Also, book publishing is way behind on Open Access. OK, OUP was willing to publish How Change Happens free online (and they swear it has actually improved sales), but most books are not. Does that mean I should stop reviewing books until they’re Open Access?

So I ran a twitter poll, and of the 113 votes, 76% supported a pledge – how about this for a text? The pledge: ‘I will not promote or link to gated journals on social media’

FAQs:

Q: Won’t this punish researcherS trying to get their work known?

A: Researchers have a number of options, from blogging the findings of their papers, to creating a landing page for their work, to publishing in draft on ResearchGate. There is no excuse for just publishing behind a paywall.

Q: Won’t this deprive social media of access to scholarship?

A: See above, plus this is part of a longer term exercise to reduce the barriers that prevent knowledge circulating

Coming Soon

more widely in society.

Q: What about books?

A: Agreed, this is tricky, since Open Access is in an earlier stage in book publishing (Google Books, and some publishers starting to go OA). But the level of price gouging in journals is far greater than for most books.

Would appreciate your help with further suggestions for FAQs and views on the topic. Unless you convince me otherwise, I will then put up a pledge for people to sign up to.

And thanks David Steven for this wonderful excerpt on pledging from Catch 22

October 23, 2017

When hate comes calling: fighting back in India

Fake news, populism and ethnic and religious hate crimes are not just a US problem. Indian activist and writer  Mari Marcel Thekaekara

laments the wave of hate engulfing her country, and celebrates some of those who are fighting back

Mari Marcel Thekaekara

laments the wave of hate engulfing her country, and celebrates some of those who are fighting back

A peace movement? The mere suggestion evokes pitying looks, even from friends. Been there, done that. In the seventies, actually. More accurately, I’m obsessed with an anti-hate movement. Because I receive regular reports of lynchings and gruesome murders from friends working on minority rights. Along with complaints that many major Indian newspapers are currently treading carefully when it comes to reporting hate crimes, primarily against Muslims, Christians and Dalits. Perhaps they are doing so because thugs claiming allegiance to the party in power can, and frequently do,

Gauri Lankesh

come down violently on critics. Last month, Bangalore journalist Gauri Lankesh was gunned down for speaking unpleasant truth to power. She was the latest in a series of such murders.

Journalists publishing stories of hate crimes, are dubbed ‘presstitutes’ by the Hindutva lobby. Hindus protesting at the subversion of Hinduism are derided as ‘sickulars’. They have an army of trolls paid to rave, rant and abuse any writer who dares to criticise the current regime.

But it’s not only journalists and intellectuals challenging the ideology of the larger family of hate spewing organisations, called the Sangh Parivar, who are at risk. Muslims, Dalits, Christians and protesting Hindus are also targeted thanks to a growing climate of hate and the warped, alarming belief that if you are not Hindu, you are not Indian. Dalits who, though classified as Hindus, have been brutally murdered by mobs known as “cow vigilantes” – a euphemism for thugs and criminals strutting across India with impunity because they claim to be protecting the cow, sacred to many Hindus. These Dalit victims are condemned by the accident of their birth into a particular caste to remove all dead animals, from cats to cows. There is no choice, it’s a caste-designated job. They are paid to dispose of the animals. They skin the carcasses to sell to the leather industry. This is the “crime” for which many young dalit men have been brutalised and murdered.

Siddarth Vardajan

It’s inevitable, given the history of Muslim conquests centuries ago, coupled with the horrors of partition, that hate and resentment will exist between many Hindus and Muslims in India. And sporadic riots are seen as just a part of life. I watched burning slums from our rooftop, as a child in Kolkata, in the sixties. And heard cries of ‘bachao’, ‘save me,’ from victims being beaten up, perhaps killed.

But for the most part, Hindus and Muslims learnt the art of peaceful co-existence. Communities mostly live separate social lives, but their livelihoods are often dependent on each other. People send each other sweets at festivals, work together amicably. Muslims fought fiercely for freedom in the Independence movement. They are Indians. They opted to remain in India during partition, because it’s where they were born and where their ancestors lived for centuries.

In the last two decades however, we’ve witnessed manufactured hate being spread around India, in a chillingly, systematic, venal process. There’s been a sustained slow release of poisonous lies, a disinformation campaign to win majority minds and hearts by instilling fear, fiddling with facts. Christians are converting illiterate, poor Hindus, they say. Fact? The Christian population has remained static at 2%. Neither two hundred years and the might of the British Empire, nor hordes of evangelising missionaries succeeded in seriously converting India.

Muslims have a dozen children each, funded by Saudi Arabia to change the demographics and make Hindus a minority in their own country is another claim. Fact? The decadal rate of population growth for Muslims is the lowest it has ever been in India’s history.

Sadly facts have little or no role to play when it comes to hate mongering. The shrillness has reached deafening decibels. But finally, more and more people are speaking out against this manufactured hate.

Harsh Mander, a former civil servant resigned in protest after the 2002 killing of over 2000 Muslims in Gujarat. Last month he led a pilgrimage to atone for the crimes against minorities. His ‘caravan’ travelled across India to visit families who’d had their loved ones brutally tortured, mutilated, then murdered. Of the 78 bovine-related (cows and buffalos) hate crimes since 2010, 97% occurred after Prime Minister Modi’s government came to power in 2014. In 46% of the cases, the police filed charges against the victims/survivors.

Hope comes too, when prominent author Nayantara Sahgal writes, ‘it is unbearable to watch my religion being

Harsh Mander. Credit: Karwan-E-Mohabbat

transformed into what it was never meant to be by people who call themselves Hindus, but practice a brutal, militant creed of their own that drives them to lynch defenceless innocent Indians, pump bullets into those who question their creed, and enter a train armed with knives to stab to death a fifteen-year-old boy who is returning to his village after his Eid shopping in Delhi”.

Then there is Siddarth Vardajan, the editor of India’s fast growing online newspaper The Wire. His paper has consistently spoken out against the hate campaign and against corruption in high places. His latest target, Jay Shah, the son of powerful politician Amit Shah, seen as many to be the force behind Modi’s throne, has earned him a £1.5million lawsuit for defamation.

I salute Harsh Mander, Nayantara Sahgal and Siddharth Varadarajan, who put their lives on the line to stand up for justice, for the idea of India.

Mander’s group seeks to begin a healing process. To form peace and reconciliation committees all over India so locals can intervene before violence starts. We need innovative, effective solutions to stop the hate campaign to prevent the disintegration of India. And we need all Indians to muster the kind of passion that emerges at an India-Pakistan cricket match, to stop the lies and the divisive disinformation that is tearing the country apart. Mander’s pilgrimage ended symbolically, in Porbandar, Gandhi’s birthplace. It was an immensely moving moment. As people sprinkled petals in the room Gandhi was born in, they said, ‘We are all Gandhi’. That, surely, is a good place to start reclaiming the idea of India, for which Gandhi lived and died.

October 22, 2017

Links I Liked

By 2022, the number of young people in middle/low-income countries who are obese will overtake the number who are underweight (with big impact on health budgets and wellbeing). Time for Oxfat?

are underweight (with big impact on health budgets and wellbeing). Time for Oxfat?

George Soros gives $18bn to his charitable foundation

Magisterial Branko Milanovic summary of what we know from the latest data on global inequality. More positive than his famous elephant graph.

Great collection of posts from the LSE Impact blog on blogging in academia (why? how? top tips etc)

I’m excited about my impending How Change Happens Canada tour 4-10 Nov, including Vancouver, Calgary, Winnipeg, Waterloo and Ottawa. Details here (Montreal to follow)

Even Africa’s Poorest Countries Are Too Expensive To Be The World’s Next Manufacturing Hub

Me on ‘Learning and Unlearning in Complex Systems’ at DFID earlier this year (and here’s the post it generated). And I need to start by learning not to talk so fast (but the looking over the top of the glasses thing is going well…..)

October 20, 2017

This Week in Africa: an amazing weekly links round-up

If you’re interested in more or less anything to do with Africa, check out ‘The Week in Africa’, an extraordinarily comprehensive round up of links by weekly email, put together by Jeff (American) and Phil (Zimbabwean) and hosted by the University of San Francicso. Sign up here.

If you’re interested in more or less anything to do with Africa, check out ‘The Week in Africa’, an extraordinarily comprehensive round up of links by weekly email, put together by Jeff (American) and Phil (Zimbabwean) and hosted by the University of San Francicso. Sign up here.

Here’s this week’s bulletin:

QUOTE OF THE WEEK

“We have never seen such devastation. Not even in our dreams.”

—Abdulkadir Abdirahman, director of Mogadishu’s ambulance service.

Greetings,

Everybody should read Lupita Nyong’o’s op-ed on Harvey Weinstein. Here is the week in Africa:

Bombing in Mogadishu

Mogadishu experienced one of the worst bombings in its history, killing more than 300 people and injuring 500 more. The video footage is devastating: it is a gravedigger’s worst nightmare. The president declared three days of mourning after the attack. The first responders are the unsung heroes. Turkey took the lead in the evacuation efforts, cementing its close ties with Somalia. Djibouti also contributed doctors. Technology played a key role in saving lives.

Before the bombing, the city was regaining stability, and Somalis in the diaspora had started to return home. But the bombing exposes security failures, as well as the possible infiltration of al-Shabab. It is possible that the attack was revenge for the botched US-led operation. Why aren’t we all with Somalia? The silver lining is that it brought shock, outrage, and resilience: Somalis volunteered in the clean up, and protested in the streets against terrorism and violence. Perhaps this provides the “break from the past” that Somalia needs. Can Somalia ever win against al-Shabab?

Liberia votes

Liberians went to the polls last week for its presidential election. Soccer star turned politician George Weah is the early leader in the count with 39% of the vote, and will face current Vice President Joseph Boakai (who had 29%) in a runoff on November 7. Could Weah win a runoff?

Kenya’s political struggle

Kenya’s electoral preparations are in shambles before next week’s vote. Election official Roselyn Akombe flees to the US after saying the IEBC is under “siege” and that the vote will not be free. Opposition leader Raila Odinga has threatened to boycott the polls. Of course, Kenyatta tells foreign powers to stay out of Kenyan affairs. Now the chairman of the electoral commission warned that he could not “truly be confident of the possibility of having a credible presidential election” because of “partisan political interests.” Clearly, Kenya’s political leaders are contributing to the political crisis. Here is everything you need to know about the situation.

Africa Confidential provides its take on the “political crisis.” This is a good briefing of the Supreme Court’s judgment. Meanwhile, Kenyan police instigated most of Kenya’s post-election violence, killing at least 33 people, Amnesty International reports. Boniface Mwangi is back at his best as an activist and protester. Aziz Rana makes the case against second-rate democracy in the country.

Ambush in Niger

Laura Seay is not happy with Rachel Maddow’s coverage of the ambush in Niger. Jason Warner provides an important overview of the terrorist affiliates in the region. John Kelly says the U.S. Special Forces are in Niger to “teach them how to respect human rights.” I’ll let Karen Attiah respond.

Struggle for rights and freedom

The Cameroonian government cracked down on protesters, arresting more than 500 people. LGBT activists worry about Trump’s impact on the continent. Resolving land disputes in Somalia is a difficult task. South Sudan’s president Salva Kiir says the country’s civil war is not his fault. This new piece examines the subtleties of authoritarianism in Museveni’s Uganda (remember: the US contributes to Museveni’s rule). The Ugandan government has arrested opposition leader Kizza Besigye, accusing him of attempted murder. This is a very interesting article about how celebrities like Jolie and Clooney interfere in the pursuit of global justice. Zimbabweans don’t want the government to monitor social media. Several people have died in Togo after an Imam was arrested. Can the UN help build a sustainable peace in Central African Republic? There is now a bronze statue of Jacob Zuma in Nigeria. Tanzanians are satisfied with democracy, but not entirely.

And there is no case for colonialism.

Plague outbreak in Madagascar

The plague is spreading at an alarming rate in Madagascar. The disease has been ruled out in the Seychelles, but health experts are on high alert. This is a helpful explainer on understanding plague in the 21st century.

Research corner

Nikki Morrison has a very interesting article about institutions and governance in African informal settlements. This new article looks at water governance in urban neighborhoods. I’m looking forward to reading Eric Kramon’s new book on electoral clientelism and vote buying in Africa. Check out the new book Understanding West Africa’s Ebola Epidemic. Congrats to Brandon Kendhammer, Abdoulaye Sounaye, and Daniel Eizenga on their new project that will examine the social impact of education on community responses to violent extremism. Jeremy Horowitz examines ethnicity and the swing vote in Kenya. Check out the new book Global Africa: Into the Twenty-First Century. The book Street Archives and City Life: Popular Intellectuals in Postcolonial Tanzania looks awesome. This book will tell you all you need to know about the history of Boko Haram.

Africa and the environment

Africa’s largest wind energy plant could relocate from Kenya to Tanzania. This is a really interesting article about how big water projects helped trigger the migrant crisis. Will the “Akon Lighting Africa” initiative electrify rural Mozambique?

The week in development

Scholars are calling for more manufacturing and industrial development in Africa. But can Africa be a manufacturing destination? One of the problems is that African labor costs remain high. Muhammad Yunus talks to Jeffrey Sachs about how to end global poverty. This new paper examines the economics of scaling up. Cheaper visas are more important than lower tariffs in boosting China-Nigeria trade. Rio Tinto is charged with fraud by US authorities. How does Equatorial Guinea spend its money? What’s behind Airbnb’s rising popularity in Africa?

“When the Revolution Came for Amy Cuddy” is a must read about research, replication, and scholarly debate. Here is Andrew Gelman’s response. I agree with Claire Adida: “A little more empathy. A little less ‘gotcha.’”

Daily life

I love this: Nairobi’s rainy days. These portraits on the streets of Senegal are pretty cool. Listen to the Bawku West Collective. Anthony Bourdain does Lagos: more here. I want to visit Addis Ababa. Congrats to the nominees for the 2017 MOBO awards. This is a cool piece: The African churches of South Delhi.

All the best,

Jeff and Phil

October 19, 2017

What did I learn from a day with the UN’s bloggers?

Had a fun day earlier this week running a blogging workshop for Unicef researchers in their wonderful centre in Florence (I know, tough gig etc). I ran through what is rapidly becoming my standard powerpoint (here you go, feel free to steal or comment ), but the most interesting (and exhausting) session was working through nine draft blogs with their authors in a group: it was a mini marathon: read the post for 5 minutes, 10 minutes of editorial discussion, then on to the next one, for two and a half hours.

), but the most interesting (and exhausting) session was working through nine draft blogs with their authors in a group: it was a mini marathon: read the post for 5 minutes, 10 minutes of editorial discussion, then on to the next one, for two and a half hours.

First thing to note was the team work – a stable of experienced writers and researchers working through their drafts together, showing excellent judgement (and kindness) in their advice and suggestions for improvements, and coming up with several new ideas for blogs and themes to explore together. They want to repeat the exercise (without me – I rapidly became redundant!) every few months as a way to support each other and generate content for the Unicef Connect research blog. One of those attending dashed off an excellent post on the pros and cons of RCTs (great title too). I’m really interested to see if they can maintain that kind of energy – do other organizations run blogging teams along similar lines?

To improve my own ‘blogging for beginners’ advice, I kept a note of some of the new (and not so new, but still worth reinforcing) ideas the emerged:

It’s all in the title: people need to spend far longer finding a title that strikes the right balance between boring platitude and blatant clickbait. Kick different options around, and ask colleagues. Questions are good; so are listicles (‘5 things you should know about X’). ‘Report back from interesting meeting’ is not. This really matters because unless people click on the title, you’ll never even get the chance to dazzle them with your prose and insights. Here’s a

My RSS feed – which titles am I going to click on?

screengrab of my RSS feed to show what you’re up against – will your title be one of the 10-20% I click on?

One Big Idea: several of the draft posts tried to convey three or more big ideas, meaning they were either way too long, or failed to do any of them justice. If you feel unclear what your one big idea/message is, show the draft to a colleague, or sleep on it and reread, and then be brutal about dropping the other stuff, or turning it into a separate post.

Man Bites Dog: a basic rule of journalism: dog bites man = no story; man bites dog = story. If you have some element of surprise in your piece, the title and lead should major on it. If there is absolutely nothing surprising, then think about leading with a human interest story (about your own life or someone else’s) to at least evoke empathy. ‘The SDGs are really important’ is just not going to get people clicking. What Harry Potter can tell us about multi-dimensional poverty probably will.

Linked to that was an interesting discussion on the best direction of ‘the funnel’ – whether posts work better if they start general (‘cash transfers are the new silver bullet’) and then go down into the specifics (‘our research in Kenya shows CTs work best when they are delivered on mobile phones’) or vice versa. Linking up to the previous point, my tentative conclusion was that if you have some man bites dog, then lead on the general, but if not, then go with the specific.

Hand holding: the more you can hold the reader’s hand with in-post commentary to engage and lure them on to the next para, the better. ‘So why should we be worried about X?’ ‘Let’s start with the upside’ rather than just plough straight into your next point.

Lose the first two paras? It was surprising how often, on reading a first draft, the group’s advice was ‘why not start with para 3?’ The first two were often ‘throat clearing’ of various kinds: saying something is important, telling us what we already know etc, before getting into the substance 3 paras in. So just start there instead.

start with para 3?’ The first two were often ‘throat clearing’ of various kinds: saying something is important, telling us what we already know etc, before getting into the substance 3 paras in. So just start there instead.

That is particularly true because every second counts – Google Analytics is a brutal witness to how quickly readers click off your post to the next thing (so far today, 1500 visitors to FP2P have stayed for an average of 83 seconds….), so you need to get the best stuff into the title and first para.

The problem of generalization: authors often panic at how little space they have to discuss something, so try and cram in lots of wisdom by using broad and often pretty obvious generalizations ‘advocacy is important to improve services’; ‘we must be more innovative’. More than a couple of those in a row, and your post is dead in the water, I reckon. Try nailing them down with a quick example, either real or hypothetical. ‘In Chile, a combined campaign by social movements and academics persuaded the government to do X’.

Links are your friend: blog readers like links to further reading, which give them the option of digging deeper or not. Links allow you to cover old ground quickly, and then get on to the new stuff rather than lose readers by rehearsing familiar arguments.

How to write about specialist stuff: a lot of the UNICEF staff are working on technically sophisticated stuff, with lots of statistics etc. The preference often seems to be to say ‘tough’ and write difficult stuff for your peers. But even your peers could be reading this in some bleary early morning befogged state and would prefer some clear writing and chunky examples to ground the discussion. I defer to my fellow Oxfam bloggers on the Real Geek blog for advice on this one

Remember it’s a diary: ‘blog’ is a shortening of ‘weblog’, so it’s meant to be first person, even if every fibre of your institutional being prefers to remain anonymous. Several people at UNICEF quoted from papers, and we only found out in discussion that they had actually written them!

Do I need to understand SEO? Webheads say that it’s essential to understand how Google’s algorithms search and rank content (Search Engine Optimization), and write your piece accordingly. Eg we were told that the first 3 words in the title must appear in the first para, in the same order, and with the same distribution of capital letters. Is this true? I’ve never taken any notice of this stuff, but that may be why so little traffic comes to the blog via Google. Should I start taking it seriously? If so, what’s the best guide to quick and dirty SEO?

Over to you, including those Unicefers present, to add any further top tips

October 18, 2017

Empowerment and Accountability in Messy Places: what’s the latest?

Spent a fascinating two days at IDS last week taking stock of year one of a 5 year research programme: Action for Empowerment and Accountability (A4EA). The aim is to understand how social and political action takes place in ‘Fragile, Conflict, Violence Affected Settings’ (FCVS) and the implications for ‘external actors’ (donors, INGOs etc, but the term always makes me think of Hollywood). The research is now getting started in the case study countries: Egypt, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nigeria and Pakistan and, although it’s early days, some really interesting and important findings are starting to emerge.

Spent a fascinating two days at IDS last week taking stock of year one of a 5 year research programme: Action for Empowerment and Accountability (A4EA). The aim is to understand how social and political action takes place in ‘Fragile, Conflict, Violence Affected Settings’ (FCVS) and the implications for ‘external actors’ (donors, INGOs etc, but the term always makes me think of Hollywood). The research is now getting started in the case study countries: Egypt, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nigeria and Pakistan and, although it’s early days, some really interesting and important findings are starting to emerge.

So what, if anything, is different about the way change happens in FCVS? My overall conclusion is that to understand these places, thinking about complex systems and power, broadly defined, is if anything even more necessary than in more stable settings. As for what the aid business can do, the Doing Development Differently/Adaptive Programming agenda is definitely a good starting point, but with some intriguing and important additions/differences.

First the system. In FCVS, the nation state is weaker, and into that vacuum step a whole range of other political players: sub-national state authorities, international aid organizations, the private sector, non-state actors like traditional authorities, armed organizations and militias, faith groups and civil society organizations.

To grasp what is happening in these messy places you need to set aside assumptions drawn from more stable places, for example on how states and citizens interact. One of the most exciting A4EA projects is developing ‘governance diaries’ in Myanmar, Pakistan and Mozambique. Local researchers interview the same families over a number of months to build up a picture of ‘bottom-up governance’ – how do people fix the problems that crop up? Who do they turn to for help? What happens next? Anu Joshi of IDS has promised to write something for the blog on how the diaries project is developing.

When so many traditional aid approaches have failed in the past, there’s a particularly strong case for looking for ‘positive deviance’ – observe the system to try and spot where it has already found solutions (total or partial) to whatever it is you are concerned about – water, environment, women’s rights etc, and then see if such outliers can be encouraged to spread.

In contexts of insecurity and fear, social norms and levels of trust become more prominent: minor shifts (eg to feeling a bit safer) in attitudes and behaviours may have a greater and more lasting effect on wellbeing than the more tangible outcomes (crops, jobs, access to services) that are typically targeted by the aid business, but can easily be swept away in the instability that characterises FCVS.

In contexts of insecurity and fear, social norms and levels of trust become more prominent: minor shifts (eg to feeling a bit safer) in attitudes and behaviours may have a greater and more lasting effect on wellbeing than the more tangible outcomes (crops, jobs, access to services) that are typically targeted by the aid business, but can easily be swept away in the instability that characterises FCVS.

So the ‘power and systems approach’ I set out in How Change Happens applies x10 in these places. For external actors, linear planning is doomed to failure – you’re only as good as your feedback loops and ability to adapt. But there are some important additions:

Things aren’t necessarily getting better: comparing our discussion with the first meeting of the researchers a year ago, we were struck by the relative optimism of 2016. Now we’re looking at what forms of social and political action are suited to a political downturn and climate of fear – a lot less is happening in public; people are spending more time on getting the framing and messages right so as not to trigger a backlash; where formal CSOs are being closed down, we need to be alert to other players expanding into the political space they leave behind. And it affects the way research can happen: A4EA projects in several countries can no longer invite media to discuss their findings – not great for your efforts to get your findings out into public debate.

The reputation of the Aid business is increasingly toxic in many places, often partly down to the West’s other foreign policy activities, such as counter-terrorism or pressure on human rights: we heard about security services coming in and saying ‘make sure there are no Americans at the meeting’; a case study of the Bring Back Our Girls movement in Nigeria was struck by its insistence that it receives not a single cent of funding from overseas.

Risk and Fear: even more than in other settings, external actors need to be acutely aware that the lives of their partners, staff and communities could be at risk if they do dumb stuff. This is not a sandpit; people are not lab rats. But also in a field dominated by political science and economics, how well do we understand fear, trust – the psychology at personal level of taking/not taking action?

There were also interestingly mixed messages on the gender dimensions of social and political action in FCVS. On

Pakistan refugee camp

the one hand the climate of fear can make doing women’s rights work much harder and more dangerous; on the other, conflict can disrupt patterns of gender oppression (women in Pakistani refugee camps suddenly find themselves more able to earn or leave the home) and activists can portray ‘women’s issues’ as less threatening to macho security forces and be allowed to carry on when other types of activism are being stomped on – I was reminded of the way ‘Mothers of the Disappeared’ groups in 1980s Argentina and Guatemala were able to turn military governments’ rhetorical commitment to the sanctity of the family into space for political action.

These initial findings are fascinating themselves, but also because the future of the aid business lies increasingly in FCVS. That’s where poor people will be concentrated, and that’s where traditional aid recipes seem to be least effective. The research funding piling into projects like A4EA and CPAID (I’ll be attending a similar event on the latter next week) is in part a consequence of that realization.

October 17, 2017

The World Bank’s 2018 World Development Report on Education: a sceptic’s review

Guest post from

Prachi Srivastava

(@PrachiSrivas), Associate Professor in the area of education and international development at the University of Western Ontario.

development at the University of Western Ontario.

When the World Bank announced that the 2018 World Development Report (WDR) would be on education, I was sceptical.

I’m not denying the Bank’s research expertise. It devotes substantial money and staff and has a trove of reports that are accessible in the public domain.

It’s also open to criticism – and receives lots of it, especially on education.

So why the scepticism?

To begin with, the Bank is one of the largest external donors for education in developing countries. ‘[M]anaging a portfolio of $US 9 billion with operations in 71 countries as of January 2013’, yet the 2018 WDR is the first since the series launched in 1978 to focus solely on education. What took it so long?

Secondly, how the Bank frames problems and assesses ‘evidence’ matters. It’s no secret that the Bank, even if implicitly, favours certain disciplines (i.e., economics) and methodological approaches (usually ‘big n’ quantitative studies). I’m not debating their virtues or vices. But this propensity has implications for the evidence that gets filtered in and out, and consequences for the ‘take-aways’. This is important because it has direct policy influence and signalling power, not only to governments and institutions with years of sectoral expertise, but also to a new community of actors, including private sector donors, with less experience in education.

Scepticism aside, the 2018 WDR Learning to Realize Education’s Promise does a few welcome things.

1. It invokes education as a basic right, and makes a strong moral case for prioritizing education and learning. The Report starts with the bold statement, ‘Education is a basic human right, and is central to unblocking human capabilities’ (p. 1), referencing Amartya Sen’s now seminal capabilities approach. Coming from the Bank, this is big.

1. It invokes education as a basic right, and makes a strong moral case for prioritizing education and learning. The Report starts with the bold statement, ‘Education is a basic human right, and is central to unblocking human capabilities’ (p. 1), referencing Amartya Sen’s now seminal capabilities approach. Coming from the Bank, this is big.

It has been heavily criticised (famously by the late Katarina Tomasevski, the first UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Education) for distancing itself from the rights-based approach in favour of an instrumental approach, and eschewing the moral imperative to act in education. While the instrumental approach remains, there are also rights-based and moral assertions. The Report even mentions examples of using litigation to claim the right to education in India and Indonesia (Box 11.3), and states that such action can work in the interests of the disadvantaged.

These are very welcome additions to the business case for education that has been taking hold. We have all heard the oft-repeated mantra (including by senior Bank staff) that education isn’t ‘just’ the right thing to do, it’s the ‘smart’ thing to do. (I’m always left wondering why simply doing the right thing isn’t enough). While the business case has become important in mobilising the will to increase education financing from donors, the Report’s opening messages on rights and moral obligations may help to reset the tone, or at least open these arguments up to a broader audience. I would have liked to see a stronger attempt at building a moral case for financing education, especially by OECD-DAC donors, many of which have not fulfilled their commitments, but this is a start.

2. It highlights the learning crisis. The Report presents evidence on learning disparities from a range of countries, particularly highlighting differences between children from richer and poorer backgrounds. It underscores the message that enrolment isn’t enough. While that message isn’t new to education researchers and policy wonks, the WDR reaches audiences (internal and external) that are likely to be unaware of the sheer extent of the learning crisis. It could have more fully assessed the evidence on the potential impact of the learning crisis on other skills (e.g., citizenship, critical thinking, creativity, ‘21st century skills’), which it begins to do (Spotlight 3), but this could have been more fully integrated.

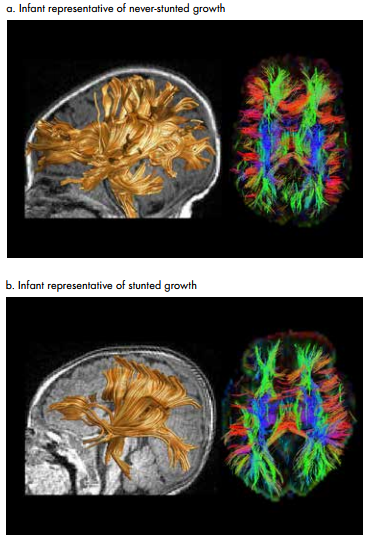

3. It demonstrates the link between neuroscience and education. The Report devotes a substantial amount of space to presenting scientific evidence on the link between deprivation, early brain development, and learning, a point also addressed in previous Education for All Global Monitoring Reports. It highlights the consequences of malnutrition and brain development for children from deprived backgrounds on learning outcomes. ‘So even in a good school, deprived children learn less’ (p. 10), and early learning deficits are generally magnified over time (p. 7).  The MRI images of the brain structure of an infant in Bangladesh whose growth was stunted compared with one whose wasn’t, are sobering (p. 115). The discussion and powerful imagery may help to press the urgency of early interventions and a more integrated approach to education delivery for deprived groups, especially in early and primary years.

The MRI images of the brain structure of an infant in Bangladesh whose growth was stunted compared with one whose wasn’t, are sobering (p. 115). The discussion and powerful imagery may help to press the urgency of early interventions and a more integrated approach to education delivery for deprived groups, especially in early and primary years.

Given the well-drawn out arguments in the Report, it is curious that this line of thinking isn’t embedded in analysing the evidence presented on school feeding programs in Burkina Faso, Kenya, and Peru (p. 148). It is also curious that evidence on India’s Midday Meal Scheme, the largest school feeding program in the world, is not cited. Young Lives analysis showed significant positive results of the Midday Meal Scheme on learning (vocabulary) in Andhra Pradesh, contrary to the studies cited.

4. It does a relatively decent (if condensed) job of presenting evidence on private sector provision and private schooling. Cards on the table—I was invited to meet with some members of the WDR Team to discuss this issue during informal consultations on the Report. Firstly, despite the unclear position on user fees the Bank has sometimes been known to take, the WDR is explicit about the negative impact of school fees and costs (p. 117). A range of policy interventions to help with schooling costs and fees are presented (e.g., non-merit scholarships, conditional cash transfers), as well as country experiences of eliminating fees (Figure 5.4, p. 118).

While it supports the theoretical assumption that competition increases quality, despite insufficient evidence in developing countries, regarding outcomes, the Report is clear: ‘there is no consistent evidence that private schools deliver better learning outcomes than public schools’ (p. 176). Huge.

The Report addresses concerns about ‘cream-skimming’ of students. Also leaving me pleasantly surprised, it is open about the potential of commercially-oriented providers to exploit incentives for profit, ‘Some private suppliers of education services…may, in the pursuit of profit, advocate policy choices not in the interest of students (p. 13).

It is refreshingly forthright in admitting difficulties in overseeing systems with a myriad of private schools, suggesting ‘governments may deem it more straightforward to provide quality education than to regulate a disparate collection of providers that may not have the same objectives’ (p. 177). Finally, the report considers systemic effects, albeit briefly, that private schooling expansion ‘can undermine the political constituency for effective public schooling in the longer term’ (p. 177). Massive.

So- the 2018 WDR makes some welcome interventions. However, to fully realise its potential, here are my top two suggestions for what it could have done better (there are others—I haven’t touched on teachers—but this post is now resembling an article):

So- the 2018 WDR makes some welcome interventions. However, to fully realise its potential, here are my top two suggestions for what it could have done better (there are others—I haven’t touched on teachers—but this post is now resembling an article):

Make the case for financing education less ambiguous. This has been raised as the main point of contention in nearly all the online reviews of the 2018 WDR (e.g., David Archer of Action Aid and Education International). And I would have to agree.

The ambiguity is incongruous with recommendations of high-level fora. For example, the Education 2030 Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action for SDG4 is unequivocal: The ‘Least developed countries need to reach or exceed the upper end of these benchmarks [4-6% GDP, 15-20% national budgets] if they are to achieve the targets’ (emphasis mine).

The discussion is also somewhat ahistorical. An earlier analysis by Mehrotra of what he termed, 10 ‘early high-achievers in education’ (Barbados, Botswana, Costa Rica, Cuba, Kerala (India), Malaysia, Mauritius, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Zimbabwe) concluded that high public expenditure as a proportion of GDP and as a proportion of national budgets were among the factors that contributed to expansion of relatively better quality primary education in early post-colonial contexts. If the aim now is to universalise education to secondary by 2030 (SDG Target 4.1), surely stable, secure, and increased financing by donors and domestic governments is pivotal, especially in countries that do not meet even the minimum benchmarks.

Focus on learning processes within schools and classrooms and their potential effects on learning outcomes. The Report acknowledges: ‘Learning is a complex process that is difficult to break down into simple linear relationships from cause to effect’ (p. 178). And it rightly attributes poor learning outcomes to poor quality provision. No one would argue otherwise.

However, ‘quality’ is influenced by a host of factors, many of which may be normative, socio-political, and micro-political (i.e., informal institutions). The learning outcomes that are the subject of the WDR are produced through learning processes structured in formal schooling processes. And formal schooling processes are embedded in the overt and hidden curriculum of the schools and classrooms (i.e., values and the reproduction of those values in formal schools) that children of different backgrounds have access to, and how those children, in turn, are positioned within them.

For example, research in India shows that broader societal caste-based practices continue to affect how children experience schooling even within universalising initiatives. Based on emerging analysis from my current study of roughly 1500 school-aged children in Delhi, I argue that silent exclusion reflects broader societal exclusion and will impede meaningful learning even if children are enrolled (see also here).

This is messy stuff. Which means that improving quality will be harder than ‘aligning all the ingredients’ (Box 9.2). These are deep-seated issues that cannot easily be overcome by the ‘proper’ incentives.

Acknowledgements: I am grateful to David Evans, a Lead Economist on the 2018 WDR Team, for sharing insights and clarifying questions on the WDR process. Any errors or misunderstandings are mine.

October 16, 2017

Links I Liked

Sooner or later every US president warrants a map (here’s Ronald Reagan’s). Nambia swung it for Trump, but I’ve got a feeling that he’ll be adding to this over the next few years. ht Alan Hirsch

How going to the movies helped Ugandan high schoolers pass their tests. This study is rapidly becoming an iconic piece of research on shifting norms/behaviours through popular culture.

Taming Big Tobacco’s efforts to subvert regulation provides a template for Big Oil, Big Pharma, and Big Food

Growth Without Industrialization? Subtle and broadly negative take on high African growth from Dani Rodrik

Chinese aid to an African leader’s birth region nearly triples after he/she assumes power. No such effect with aid from the World Bank

‘When I showed Duterte the pictures, he said, “You want me to kill them?”’ Interview with Philippines’ activist Environment Minister

A Dutch Daily Show take on US’ gun addiction (3m)

Crazed Lefties on the Loose: IMF says higher taxes for rich will cut inequality without hitting growth. And here’s the video

October 15, 2017

It’s World Food Day today – why is global progress going into reverse?

Guest post from Larissa Pelham, who is a food security wonk with probably the longest job title in Oxfam (see end for its full glory)

(see end for its full glory)

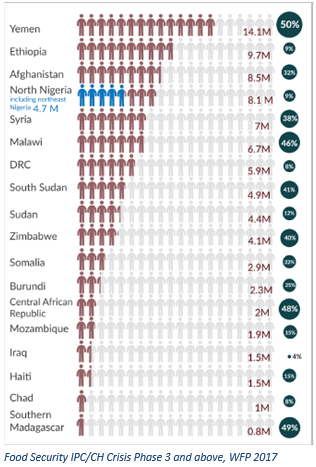

World Food Day has come around again and with it the annual report on the State of World Food Insecurity. In a year which declared a potential ‘four famines’ – with South Sudan tipping into famine in March, it is perhaps unsurprising that the numbers of food insecure have increased to 815 million, the first rise in well over a decade. This blog unpicks the figures and trends and reflects on what this means for Oxfam’s humanitarian work.

How is food insecurity quantified?

This year’s annual review introduces two substantial changes. Firstly, nutrition is now included as a core component of the report’s food security analysis, (albeit not the quantification), reflecting the commitments in the SDGs to make a more concerted effort to address the multiple factors behind food insecurity.

This year’s annual review introduces two substantial changes. Firstly, nutrition is now included as a core component of the report’s food security analysis, (albeit not the quantification), reflecting the commitments in the SDGs to make a more concerted effort to address the multiple factors behind food insecurity.

Secondly, a change in the way food insecurity is measured, including a new FAO indicator that actually asks real people about their ability to access food in the past year, from concerns about being able to afford it, to skipping food for entire days. Reassuringly, this more nuanced analysis, focused on people’s own perspectives of their situation turns out to be strongly correlated with the conventional methods of quantification

What the data tells us.

The data reveals 38 million more people food insecure in 2016 compared with 2015, a reversal of the trend over at least the past 15 years (bringing the total to 8-11% of the world’s population depending upon the measure used). The reasons are complex. Firstly, there is the worrying rise in numbers and prevalence in particular regions, notably east Africa (33.9% prevalence), mid-Africa (25.8%) and the Caribbean (17.7%), with Africa slipping back to the prevalence it experienced a decade ago.

On the nutrition side, despite a 22% reduction in stunting in the last decade, 630 million children under 5 – a horrifying 38% – are categorised as ‘malnourished’ – whether through wasting, stunting or being overweight. All this has implications for individual productivity, economic growth and government health budgets.

Thirdly, anaemia affects 33% of women globally, with impacts on the later nutrition of children, on susceptibility to  disease and poor health. Whilst breastfeeding has improved (with prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding up to 6 months at 43%) there are some notable outliers, such as the UK, which in 2016 reported the lowest levels of breastfeeding in the world.

disease and poor health. Whilst breastfeeding has improved (with prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding up to 6 months at 43%) there are some notable outliers, such as the UK, which in 2016 reported the lowest levels of breastfeeding in the world.

The analysis points to three principles for overcoming food insecurity: (i) nutrition (ii) it requires coordination across multiple sectors and for Oxfam that means linking particularly with our WASH, gender and protection work; and (iii) these challenges demand different approaches across time, context, country and gender.

What are the main drivers of food insecurity?

The report defines two main drivers of acute (ie short term) food insecurity: conflict and natural disaster, both growing and both major causes of the close to 1 billion displaced people in the world. These days people are displaced for an average of 17 years, mostly living in host communities rather than camps (only 10% of the total) and are only 25% are international migrants – the rest remain in their countries or origin as internally displaced people (IDPs).

With half of food insecure people living in states of conflict/civil war, food insecurity is both a factor and symptom of conflict: pressure on natural and public resources, decreased agricultural production caused by climate change and  strong weather cycles raises tensions (rising food prices sparked riots in 40 countries in 2007-8); but conflict also causes displacement limiting access to food sources. All ‘four famines’ occurred in places affected by conflict. Reducing food insecurity and peace-building are mutually reinforcing.

strong weather cycles raises tensions (rising food prices sparked riots in 40 countries in 2007-8); but conflict also causes displacement limiting access to food sources. All ‘four famines’ occurred in places affected by conflict. Reducing food insecurity and peace-building are mutually reinforcing.

So what else can Oxfam and NGOs do to overcome food insecurity?

What this tells us is that the acute caseload we focus on actually isn’t so short term after all. We must focus our food security efforts on contexts of fragility, conflict and displacement, and think long term.

One set of interventions in our toolbox, emphasised by the report, is the role of social protection, broadly defined as predictable formal and informal transfers and services (including subsidies and allowances) to all or some of the population to prevent or overcome poverty and vulnerability (comprehensive social protection also covers access to basic services health, education and water). Cash transfers can bridge the divide between humanitarian assistance and longer term safety nets, provide predictable income support in the face of uncertain access to basic needs. Cash for work schemes can build livelihoods, infrastructure and productive assets. Community approaches can improve social cohesion, although some recent research is more cautious about the governance benefits from social protection. NGOs can – and Oxfam does – influence and assist government to help establish such systems (Niger), pilot projects that governments can take to scale (Kenya); work with community structures (Burkina Faso) and demonstrate that even in the most fragile of settings, fledgling social protection is still possible (Yemen).

The report also acknowledges the importance that informal structures play in food security: community networks are the provider of first resort in crises (in 2015 remittances to developing countries were more three times greater than official aid). But such structures of social exchange are weakened by conflict. As an NGO, we are well-placed to support informal mechanisms. It is critical that we pay attention to what is happening with the informal sector and provide support there, before it is undermined. Oxfam wants to see new measurements of food insecurity which take into account the changing nature of these social networks, as an early indicator of descent into acute food insecurity.

(In case you were wondering about Larissa’s job title, it’s Emergency Food Security & Vulnerable Livelihoods Adviser – Social Protection & Resilience, Global Humanitarian Team. Can anyone beat that?)

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers