Duncan Green's Blog, page 104

January 1, 2018

Links I Liked

Welcome back, those who’ve been away. The twittersphere never stops, so here’s some random links to help you  catch up.

catch up.

48 superimposed photos of the sun, taken during a year, one per week, in the same place and time, in the Cathedral of Burgos. The highest point is the summer solstice and the lowest is the winter solstice. But can someone please explain to me why it’s a figure of 8, rather than an ellipse? h/t Roberto Alonso González Lezcano

Excellent post by USAID about how to better ensure evidence is used by decision-makers. h/t Michael Zanchelli

Ten commandments each for economists and non economists, from Dani Rodrik. But why divide up the world like this rather than, say, ‘anthropologists and non anthropologists’?

Hieronymous Bosch does Twitter, h/t Paul Cooper

Hieronymous Bosch does Twitter, h/t Paul Cooper

Geek heaven. Inaugural Statistic of the Year award. 2017 winner is 69 (= number of US citizens killed on average in lawnmower accidents each year, compared with the two killed by immigrant Islamic terrorists.)

Important piece on geo-engineering as a development issue from Andy Norton of IIED: ‘none of the techno-solutions under consideration will have equitable impacts between rich and poor nations, between powerful and powerless people.’

What’s happened to civic activism in Brazil? Excellent from Marisa von Bülow. On the surface, all is apathy. Below it, two kinds of campaign are filling the vacuum: moral panics from the right and defensive activism from the left

Extraordinary way to run a discipline, and a great title: The Running of the Economists

December 20, 2017

See you in 2018 people, and please wish me luck in Tromso

Got a bunch of things to get finished before Christmas, and judging from the falling number of blog readers (thanks, Google Analytics), so has everyone else. So for everyone’s sake, I’m calling a blog break til the New Year. After Christmas I’ll be heading off to the top of Norway to try and see the Northern Lights.

If there are clear skies, it could like this

On the other hand, if it’s cloudy, it will be dark 24/7 and the view will be more like this…….

In other words, a high risk holiday.

Have a good break (if you’re taking one) and see you in 2018.

Oh, and it’s the shortest day of the year today (if you’re in the Northern Hemisphere), always a good time to reread John Donne’s A Nocturnal upon St. Lucy’s Day.

December 19, 2017

Why is Support for Women’s Rights Rising Fastest in the World’s Cities?

Guest post by Alice Evans

Support for gender equality is rising, globally. People increasingly champion girls’ education, women’s employment, and leadership.

Scholars have suggested several explanations for this trend:

(a) the growing availability of contraceptives (enabling women to delay motherhood and marriage);

(b) domestic appliances (reducing the volume of care work);

(c) cuts in men’s wages and the rising opportunity costs of women staying at home; and

(d) seeing women in socially valued roles.

These theories are plausible. But can they account for rural-urban differences?

Across Asia and Africa, urban residents are more likely to support gender equality in education, employment and leadership than their rural compatriots. This holds even when controlling for age, education, employment, income, and access to infrastructure. Likewise, in the 2016 US elections, city-dwellers were more likely to support Hillary Clinton (controlling for geographic region, education, income, age, race, and religious affiliation). Why is this?

Note: There is a poll embedded within this post, please visit the site to participate in this post's poll.

To explore these possibilities, I undertook ethnographic research in rural and urban Cambodia and Zambia: living in rural and urban areas; interviewing migrant workers; farmers; fishermen; traders; students; teachers; office-workers; politicians; and government officials.

My data suggests that cities can catalyse gender equality because they: (1) raise opportunity costs; enable (2) exposure to alternatives; (3) association; and (4) proximity to services.

My data suggests that cities can catalyse gender equality because they: (1) raise opportunity costs; enable (2) exposure to alternatives; (3) association; and (4) proximity to services.

First, cities often raise the opportunity costs of gender divisions of labour: higher living costs; more economic opportunities for women (in services and manufacturing); and the contemporary precarity of male employment. These macro-economic changes mean that urban Zambian and Cambodian families increasingly see women’s work as advantageous.

Second, cities enable exposure to alternatives. People living in interconnected, heterogeneous, densely populated areas are more likely to see women in socially valued, masculine domains. Seeing women mechanics, breadwinners and leaders increases people’s confidence in the possibility of social change. This catalyses further experimentation, and generates a positive feedback loop.

Third, cities enable association with diversity. People may shift their norm perceptions (beliefs about what others think and do) by chatting and sharing ideas in cafes, markets, and offices: seeing others condemn inequalities, demonstrate zero tolerance of abuse, and champion women leaders.

Nsenga (41, circular migrant, fish wholesaler): In the village, there are no educated women for girls to look up to, so they don’t aspire for employment.

Annie (45, widow, circular migrant, fish wholesaler): But here in town, there are nurses, teachers, doctors. Girls think, ‘if I am educated then I can be a doctor’. Here in town children see everyone going to school but in the village, they just see two people…

Nsenga: Here in town a woman may stop school to give birth, then she will be desperate to return to school and finish. But in the village, they just give birth and it’s all over. It’s because of early marriage. There’s nothing else they see and aspire for [translated from Bemba].

Alice: What do you think of Phnom Penh? [speaking to trainee flight attendants]

Son: I meet new people, we share our experiences. But in rural areas, we just stuck with the old ideas. The idea is stuck because we don’t go out. [Here in the city] I feel wonderful. Seeing women dress up beautiful, earn their own living.

Bopha: I saw a woman driving a tuk tuk.

Son: Now it’s common.

First author: How did you feel, seeing her?

Bopha: I feel strange. Why don’t she find other job, like seller or company? I’ve never seen that before.

Son: It really impressed me, because what a man can do a woman can do…

Chanda: It shows men I can do it.

This process is much slower in rural Cambodia and Zambia. Rural remoteness and homogeneity curb exposure to alternatives, dampening confidence in the possibility of social change, deterring deviation.

Fourth, urban women are closer to health and police services – so potentially more able to control their  fertility and secure external support against gender-based violence. But if these service-providers are unhelpful (e.g. blame victims), then proximity is no safeguard.

fertility and secure external support against gender-based violence. But if these service-providers are unhelpful (e.g. blame victims), then proximity is no safeguard.

Urban experiences are also mediated by macro-economic context, the sectoral composition of job growth, and occupational status. While Zambian market traders learn from a bustling diversity of assertive women, home-based workers are more socially isolated. There are also limits to Cambodian factory work: long hours, berated, harassed, and closely controlled. Breaks are brief: gulp a sugary drink, guzzle a plate of rice and fatty meat, compare bundles completed, then hasten back for the bell.

In sum, cities seem to catalyse slow, incremental progress towards gender equality, by

(1) raising the opportunity costs of economic inactivity;

(1) raising the opportunity costs of economic inactivity;

(2) amplifying exposure to alternatives;

(3) enabling association with diversity; and

(4) increasing proximity to services.

Cities may also catalyse other dimensions of socio-political change – e.g. social mobilisation, democratisation, and accountability. People living in interconnected, diverse, densely populated areas are more likely to hear critical discourses; see slogans of resistance emblazoned in street art; learn about successful activism; realise widespread support for change; and gain confidence in the possibility of reform.

December 18, 2017

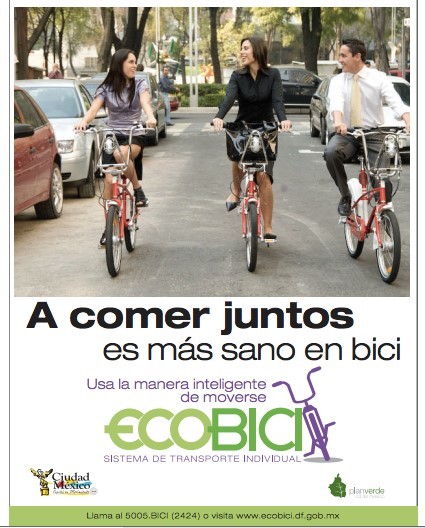

What can other cities learn from Mexico City’s bike-sharing scheme?

Some smart thinking from one of my LSE students from last year, Naima von Ritter Figueres. Originally published on the LSE International Development blog

on the LSE International Development blog

Most cities over the past few decades have been shaped by the car. Heavy traffic, air pollution, safety hazards, and losses in public space, social cohesion and economic competitiveness are all associated with the ever-increasing unsustainable dependence on this form of transport.

Mexico City’s Bike-Sharing System, EcoBici

A growing number of cities are therefore returning their attention to the humble bike as one viable alternative for individual transport. Bike-sharing systems (BSS), in which bikes are shared by users for short distances, are being introduced as one element of a new sustainable mobility paradigm. They offer a host of benefits including reduced congestion and fuel emissions, transport flexibility, health benefits, and financial savings for individuals. Such systems are said to be one of the most promising sustainable urban planning interventions and are now present in more than 1000 cities worldwide

Despite this recent interest, BSS face a host of barriers, categorized as institutional, physical, and socio-cultural lock-in mechanisms – or incumbent forces that tend to maintain the status quo. These lock-ins help explain why progressive interventions such as BSS are often delayed or prevented, particularly in developing country mega-cities. Mexico City is an exemplary case of a mega-city where car-centric lock-in mechanisms have long worked against change in the mobility system. The table below provides an overview of these.

Institutional, physical, and socio-cultural lock-in mechanisms for Bike Sharing Systems in Mexico City

Socio-cultural lock-ins in particular are often forgotten. At the same time they are usually the most difficult to overcome due to their intrinsic nature associated with individual beliefs and attitudes.

For instance, in many places, including Mexico, the bike has long been rendered the “poor man’s” mode of transportation while the car is seen as a symbol of success. In Mexico, the term “pueblo bicicletero” (biker village) denotes a poor village, and the image of a biker being of someone who is poor and not able to afford to buy a car. Such social perceptions have a strong cultural lock-in effect.

This lowly perception of the bike is reinforced by the mindset of many car drivers who believe they have the priority in the city landscape. Cycle paths and parking spots can be seen to detract from car spaces, sometimes leading to aggressive behavior by the ‘entitled’ car drivers. Such attitudes maintain car drivers’ domination in Mexico and elsewhere, and scare away potential bike users.

In order to address these barriers, Mexico City took on a comprehensive and creative set of measures.

First, the city decided to change the image of the bicycle by branding the bike-share scheme as “la manera inteligente de moverse” (the intelligent way to travel): it is healthy, helps the planet, and reduces travel time. This helped engender a new profile of a cyclist: one who is middle class, educated, and for whom biking is a choice rather than an economic necessity. The bicycle has thereby gained visibility, social acceptance, and legitimacy.

Bike-Sharing systems poster for Mexico City

Second, the city decided to address aggressive driver behavior through a specific communications campaign to educate drivers on the benefits of cycles. Messages included, for instance, “One cyclist is one less car on the road for you to arrive to work faster” and “One cyclist is one more parking spot open for you.”

Another distinguishing feature of EcoBici is the use of yearly perception surveys with questions ranging from user profile, travel characteristics, transport habits, and the impact of Ecobici on the user.

The viability of EcoBici and the overall image of biking has been transformed. The program, which started in 2010 with 85 docking stations and 1000 bicycles, has expanded to over 446 docking stations and 6000 bicycles. User demand averages 34,000 daily users. EcoBici is the largest in the region and has been replicated in other Latin American cities. In addition, CDMX won the 2013 Ciclociudades Award.

Ecobici has

reduced 8% of taxi use and 5% of private car use,

reduced carbon emissions by 499 tons of CO2, and

saved more than 2,000 days in aggregated travel time.

In addition, roughly 82% of users have reported positive changes in their quality of life:

44% are more relaxed,

38% save money,

36% have improved physical condition, and

26% have more time.

Mexico is not the first and certainly not the last city to move toward sustainable mobility. As urban populations grow, traffic worsens, pollution soars, and a greater awareness arises around climate change, it is increasingly necessary to understand how successful transitions away from the private motorized vehicle toward more environmentally sound, efficient, and shared options can be promoted. Mexico City’s EcoBici bike-sharing program shows specific ways in which the lock-ins of the incumbent motorized automobile system were intentionally and holistically addressed. The success story of EcoBici may inspire other cities, some still to be built, that a transition toward BSS is possible, including in an emerging economy mega-city.

A major opportunity is the fact that 60% of the urban areas needed by the end of this century still remain to be built and that mobility systems for those cities are still in their formative stages. An overwhelming majority of these urban areas will be in developing countries. Hence, efforts towards more sustainable urban mobility are both timely and necessary to avoid the long-term lock-in of highly polluting automobility systems.

One of the mayors of Lyon, France, famously said: “There are two types of mayors in the world: those who have bike-sharing and those who want bike-sharing.” In the 21st century, two hundred years after the invention of the bicycle, we may finally see a world with an overwhelming majority of the first kind of mayor. Those cities will be less congested and polluted; they will operate according to sharing principles, they will be more livable and breathable. Those cities may be planned and built not for auto-mobility but for citizen mobility.

Naima von Ritter Figueres (@naima.v.r) is a recent graduate of the MSc Development Management programme. Her Master’s thesis, Lock-In Does Not Lock Out: Bike-Sharing in the Transition Towards Sustainable Urban Mobility, investigated systemic barriers and opportunities of introducing bike-sharing systems in megacities, with a specific case study on Mexico City’s EcoBici program. She is currently an Ambassador for Art / Earth / Tech Institute co-leading research on shared living trends. You can email her at naima.ritter@gmail.com.

December 17, 2017

Links I Liked

Some pleasing funnies this week, via Robert Went and Amy Klatzkin

Some pleasing funnies this week, via Robert Went and Amy Klatzkin

‘Cash transfers reduced tobacco and alcohol consumption’, according to a meta-analysis of 19 studies. Possible reasons: CTs encourage other spending on good stuff (health, education); people following the advice on how to spend that often accompanies CTs; and CTs usually go to women & increase their say in broader household spending.

Does your social circle determine how much you care? 9m TedX talk by David Hudson summarizing his research on social networks, filter bubbles & ‘circles of compassion’.

Which countries host the most refugees? Germany the only Northern/’developed’ country in the top 10 h/t Conrad  Hackett

Hackett

An A to H of key lessons from the AIDS movement’s success that could be applied to help bring non-communicable diseases under control.

The traders cashing in on Rohingya misery: ‘It’s the best profit of my life‘

Endless reports on rising poverty do little to change government policy – there’s another way

Indulge a proud parent for a moment. My son Calum co-directs the London Community Land Trust, a fascinating effort to find new ways to solve the capital’s housing crisis. They just won first prize in the Guardian’s Architecture and Design Events for 2017. Cool, eh?

And an epic TV gotcha. CNN interviewer Jake Tapper floors Roy Moore spokesman Ted Crockett with a spot of truthiness. Delightful

December 14, 2017

What did I learn in Myanmar about what Adaptive Programming actually looks like?

I’m still processing a fascinating week in Myanmar. No I wasn’t in Rakhine, in case you’re wondering (separate post  on that may follow). Instead, along with aid programming guru Angela Christie, I was exploring what ‘adaptive management’ looks like on the ground, and how it compares to all the fine-sounding stuff repeated endlessly in aid seminars around the world.

on that may follow). Instead, along with aid programming guru Angela Christie, I was exploring what ‘adaptive management’ looks like on the ground, and how it compares to all the fine-sounding stuff repeated endlessly in aid seminars around the world.

The lab rat for this was Pyoe Pin, one of a handful of examples of adaptive management that is regularly cited (eg in this 2014 paper by David Booth and Sue Unsworth). It’s DFID’s baby, and has been running since 2007. Its purpose (according to one of the deluge of reports we were obliged to read) is to:

‘support civil society, private sector and government to work together to address problems and identify locally-led solutions. Supporting coalitions focused on specific issues that local actors care about has led to results that have had both an intrinsic value – including reforms in important areas such as land, education, health, forestry, legal aid and freedom of association, impacting the lives of millions of people – and have also contributed to changing the ‘rules of the game’ to be more inclusive, open and fair.’

Pyoe Pin does this through a combination of political economy analysis, grants, technical advice and getting people into the room to talk. PEA helps spot potential reform windows and supporters. As a funder it can hand out small and medium sized bits of money quickly when it spots an opportunity; it can bring in experts, whether from Myanmar or outside, to push along a discussion; and it spends a lot of time building what it calls ‘Coalitions of Interest’, which are not necessarily the same as (formal) coalitions – the PP approach is more fluid than that.

Its focus is on finding winnable reforms by aligning incentives, which seems pretty wise in a conflict-ridden environment like Myanmar, where stoking protest movements and opposition is unlikely to end in anything good.  We looked at a particular example – getting reform of the fisheries laws to include a lot more small fishing families and weaken the cartel of big business interests that previously had a lucrative lock on the fishing license system. Pyoe Pin funded and supported small fishers to organize, built links with legislators, persuaded reformers to leave the cartels enough of a slice of the action to weaken their opposition, and took the resulting ‘coalitions of interest’ to Cambodia to see fisheries reform in action. It worked a treat, and new laws are already transforming lives on the ground, as we saw on a visit to a fishing community in the Ayeyarwaddy region.

We looked at a particular example – getting reform of the fisheries laws to include a lot more small fishing families and weaken the cartel of big business interests that previously had a lucrative lock on the fishing license system. Pyoe Pin funded and supported small fishers to organize, built links with legislators, persuaded reformers to leave the cartels enough of a slice of the action to weaken their opposition, and took the resulting ‘coalitions of interest’ to Cambodia to see fisheries reform in action. It worked a treat, and new laws are already transforming lives on the ground, as we saw on a visit to a fishing community in the Ayeyarwaddy region.

We spent a week with Pyoe Pin staff, partners, aid donors, and other CSOs and came away pretty impressed, but also aware that the story is both more nuanced and more interesting than the standard narrative. We’ll be writing a paper on that (and I will doubtless stick the draft up on the blog when it’s ready), but here are a couple of preliminary thoughts:

Being ‘adaptive’ works on (at least) two levels, and in very different ways

Adaptive Management is a way of doing development differently in the day-to-day. Instead of implementing The Plan, everyone from frontline to back office thinks on their feet, continuously navigating through a fog of complexity, ambiguity and uncertainty. They do this through a mix of curiosity, evidence, emotional intelligence and plain old instinct (the test, as Angela put it, is whether your staff or partners spot and react to ‘the frown on the face of the minister’). From that, they generate best guesses for what to try next, then test and correct (call it ‘dancing with the system’)

Adaptive Programming: This is a more deliberate and conscious process of staff standing back periodically, commissioning ‘political economy analyses’, bringing in critical friends etc to review the way the work is developing and chart the course for the next period.

Because of the aid business’ fascination with procedures, reporting etc a lot of the attention has been on Adaptive Programming, but we came away with the view that the day-to-day stuff of adaptive management is at least as important. And it raises some big questions:

Reporting: Good dancers often find it very difficult to describe how they dance, but that is what is required if you

Very different from learning TO dance

are to keep your donor happy. This is not about inventing some bogus ‘we reduced poverty by 34.6%’ stat to keep the minister at bay, but taking donors with you on the dance – capture and explain ‘critical moments’, like how you responded to the frown and what happened next (management) or decided to continue/end a particular piece of work (programming).

People: I’m English so I know how hard it is to teach people that can’t dance to do so….. Adaptive Management stands or falls on soft skills (emotional intelligence, empathy) that are extremely hard to train into people. So you need to recruit the right people, and give them the freedom to work adaptively. Pyoe Pin also encourages its staff to spend time exchanging dance tips between practitioners working in different fields (it works on 9 issues – Fisheries, Garments; Natural Resource Governance: Land, Forestry, Extractives; Education, Maternal and Child Health, HIV and Access to Justice).

But what else might help? Mentoring seems to be becoming more common in the aid business, and holds potential, but really helping staff become top dancers might require something more formal like an apprenticeship – shadowing a veteran staffer for 6 months as part of an induction. That sounds expensive, but could save years of ‘learning by failing’.

Which more or less fleshes out my mid-trip video on why this kind of approach is particularly relevant to fragile and conflict-affected situations.

December 13, 2017

I want to convince you about the importance of universal healthcare – should I talk about numbers or people’s lives?

Tuesday was Universal Health Coverage Day. Anna Marriott

, Oxfam’s

Public Services Policy Manager reflects on  the global campaign for decent healthcare

the global campaign for decent healthcare

If you operate outside of the global health bubble, you could be forgiven for not noticing that the 12th December was Universal Health Coverage day. A day that marks the anniversary of a 2012 UN commitment to ensure that everyone, everywhere gets the quality health services they need without suffering financial hardship. Yesterday, the World Health Organisation and the World Bank launched a new global UHC monitoring report that uses brand-new agreed SDG indicators to measure progress (indicators that Oxfam with others successfully pushed to change last year). Even for us hardened health advocates the findings of the new report make for very uncomfortable reading and are a damning indictment of government (in)action:

The facts in brief:

At least half of the world’s 7.3 billion people do not have full coverage of essential health services;

the number pushed into extreme poverty by spending on health has been left unchanged (100 million per year);

the number facing severe financial difficulties because of health expenditure has risen sharply since 2000 (800 million per year).

Health service coverage has been increasing at an unacceptably slow pace of just over 1% per year.

The richest mothers and infants are four and half times more likely than the poorest to receive essential maternal and child health interventions in low and lower middle-income countries.

The report is packed with fascinating and disturbing new facts and figures and an annex with country by country data (where it is available). I encourage anyone concerned about their own national progress to read it. As a champion for UHC, one finding was particularly important: access to health care really does matter – life expectancy is 21 years higher for those countries with the best health coverage in comparison to those with the worst, AFTER controlling for a country’s income and average education levels.

The report is packed with fascinating and disturbing new facts and figures and an annex with country by country data (where it is available). I encourage anyone concerned about their own national progress to read it. As a champion for UHC, one finding was particularly important: access to health care really does matter – life expectancy is 21 years higher for those countries with the best health coverage in comparison to those with the worst, AFTER controlling for a country’s income and average education levels.

But we work in a sector full of such killer facts. I have been privileged over the last 12 months to hear first-hand many of the human stories behind these numbers. Stories which for me have had a much more profound and long-lasting impact. I have listened to parents reduced to watching their children die in front of them because they have run out of money for medical care; children pulled out of school to work to help pay off household health care debts; women nearly always making the multiple sacrifices to pick up the burden of unpaid care for the sick when governments don’t deliver; and I even met patients locked up in health facilities against their will because they were too poor to pay their fees. One of these stories is captured in this short film.

I want to tell you about another.

I met Ann Marie (a year ago this week) in her one room shack in a slum on the outskirts of the capital city of Cameroon. She lives there with her two children and her mother. Her mother is sick and disabled, caused by untreated diabetes. Ann Marie tries to massage her pain away for what seems like hours every day. She feels overwhelming guilt that she cannot do more. Every month is a struggle. Rent to pay. Food to buy. Whether her two children go to school depends on how much pain her mum is in. It’s school fees vs medicines for pain relief. When her mum is really unwell, Ann Marie has to stay home from work to care for her, but risks losing her job and doesn’t get paid. She could keep her daughter home from school to look after her mum instead, but knows she would be denying her the chance for a better future if she does.

Ann Marie’s story is the best explanation I have ever heard of for why free, equitable, truly universal and quality health and education are so crucial in the fight against poverty and inequality; for building fairer more productive economies and for transforming women’s lives.

There are numerous powerful arguments to be made, all backed up by robust evidence, of the economic returns to be gained from investment in healthcare for all. These are important and they may be the most influential for convincing finance ministers around the world that greater public funding for health will more than pay for itself. But surely the most important argument that we must win is that compassionate, effective health care for all is a reflection of our basic humanity. It is hard to imagine a greater vulnerability than being seriously sick or injured with no means or power to get the healthcare you need. Free universal decent quality health care is possible and affordable. We just need a radical change in approach to achieve it.

How to stop men asking all the questions in seminars – it’s really easy!

I spotted a short item on gender bias in academia in the Economist this week and tweeted it, which then went viral.  The tweet read:

The tweet read:

‘In academic seminars, ‘Men are > 2.5 times more likely to pose questions to the speakers. This male skew was observable only in those seminars in which a man asked first question. When a woman did so, gender split disappeared’. CHAIRS PLEASE NOTE – FIRST Q TO A WOMAN – EVERY TIME.’

Which confirms an impression I’ve had when chairing assorted discussions – if you let men dominate from the start, it stays that way, but call on women for the first few questions, and things work out much better.

The research paper that backs up the stats can be found here. It’s based on survey responses of over 600 academics in 20 countriesand observational data from almost 250 seminars in 10 countries. Kudos to the authors, Alecia Carter, Alyssa Croft, Dieter Lukas and Gillian Sandstrom. Their broader recommendations are:

‘Increasing the time for or number of questions reduces the imbalance in the questions asked. We recommend that, where possible, the question time not be limited. This could be achieved through, for example, booking a seminar room for longer than one hour so that the next event in the room does not cut short the question time. Having said this, our data suggest that to overcome the male-first question bias, upwards of 25 min is needed for questions, which was a rare occurrence in our data and additionally may be a taxing requirement for the speaker after having given a seminar.

Alternatively, keeping questions and answers short will allow more questions to be asked during a given question period, and could be an alternative method to allow greater balance in the questions asked. We feel that more could be done through active changes in speakers’, attendees’ and particularly moderators’ behaviour. Having an active, trained moderator may avoid those situations where one audience member seems to be “showing off” (which survey respondents claim to be the case quite often), or is going off-topic, or a speaker who goes over time.

We would recommend that, should the opportunity arise, a female-first question be prioritised because this was a good predictor of low imbalance in the questions asked in our observational data. In addition, moderators could be trained to see the whole room (location was mentioned as a factor), and to maintain as much balance as possible with respect to gender and seniority of question-askers. In the open-ended survey questions, respondents complained that moderators call on people they know or more senior people, overlooking the rest.

Although it may seem fair to call on people in the order that they raise their hands, doing so may inadvertently result in fewer women and junior academics asking questions, since they often need more time to formulate questions and work up the nerve.

Although it may seem fair to call on people in the order that they raise their hands, doing so may inadvertently result in fewer women and junior academics asking questions, since they often need more time to formulate questions and work up the nerve.

Our data clearly show that women are not inherently less likely to ask questions when the conditions are favourable—there is no gender bias when a woman asks the first question. Our suggestions should be seen as aims to create favourable conditions that remove the barriers to speaking up and being visible.’

One of the single most useful bits of gender-related research I’ve read in a long time. I will do things differently from now on.

Update: most useful additional advice on twitter comes from Joe Smith. He attended a recent seminar where the chair announced he would take Qs in order ‘girl-boy-girl-boy’. Lets people know in advance, is obviously fair, and is light hearted and infinitely preferable to male chair ‘look how feminist I am’ trumpet-blowing.

December 12, 2017

How are INGOs Doing Development Differently? 5 of them have just taken a look.

Hats off to World Vision for pulling together some analysis on where large international NGOs (INGOs) have got to on  ‘Doing Development Differently’ (see the 2014 manifesto if you’re not up to speed on DDD). Up to now, NGOs have been rather quiet in a discussion dominated by government aid agencies, academics and thinktanks. World Vision asked Dave Algoso to look at examples from 5 INGOs (CARE, IRC, Mercy Corps and Oxfam, as well as WV), and he’s produced a pleasingly brief 10 page summary of what he found. Here are some highlights:

‘Doing Development Differently’ (see the 2014 manifesto if you’re not up to speed on DDD). Up to now, NGOs have been rather quiet in a discussion dominated by government aid agencies, academics and thinktanks. World Vision asked Dave Algoso to look at examples from 5 INGOs (CARE, IRC, Mercy Corps and Oxfam, as well as WV), and he’s produced a pleasingly brief 10 page summary of what he found. Here are some highlights:

Summary: ‘The contributions that INGOs can make to the DDD movement stem from their positioning within the development sector. Their programmatic experiences and in-house expertise differ from those of academics, think tanks, donor agencies, contractors, and national or local NGOs and community organizations. INGOs’ contributions to the conversation fall into three major themes:

Localizing power and ownership in DDD practice. The DDD manifesto emphasizes the need to address local problems, defined by local people in locally owned processes, legitimized at all levels. To reach the most marginalized people and communities, INGOs wrestle with the power imbalances that often prevent those communities from engaging in development processes. Many INGOs have developed specific practices and techniques that make this possible.

Funding and accountability for adaptation. Though not mentioned in the manifesto, the effect of funding modalities on adaptation, accountability, and partnerships has been a frequent discussion topic at DDD gatherings. INGOs sit at the centre of the rapid cycles of blended design and implementation that characterize DDD practice. They are learning to navigate the constraints set by funding and compliance, while also defining better forms of partnerships that actively encourage adaptation.

Institutionalizing DDD across large agencies. From the first workshop, the DDD community has wrestled with how to best spread the principles. INGOs have contributed to the public body of knowledge, but the bulk of their effort has been focused on internal reforms. Each organization interprets the DDD principles in terms of their specific mission, contexts, and approaches, increasing the likelihood of the practices taking root across their broad portfolios.’

Of these three, I found the more in-depth explanation of the second point the most substantive:

‘The topic of funding is impossible to avoid in discussions of development approaches. INGOs’ position in the development ecosystem means they are often working directly with both the sources of funds and the communities meant to benefit from them. As a result, they often find themselves trying to do development differently while resourcing development in the same old ways. This can lead to some contradictions, which INGOs are learning to address.

Insight : Flexible funding, in one form or another, is needed for DDD

Most development funding involves planning and budgeting practices that constrain how a program adapts in response to local needs. Strict budget lines or the incentives to spend quickly and steadily (through high “burn rates”) often prevent teams from re-allocating resources when pre-planned activities become less relevant and a program needs to change direction. These factors make it much harder to blend design and implementation, to learn and iterate, or to make “small bets” that may be replicated or dropped.

Most development funding involves planning and budgeting practices that constrain how a program adapts in response to local needs. Strict budget lines or the incentives to spend quickly and steadily (through high “burn rates”) often prevent teams from re-allocating resources when pre-planned activities become less relevant and a program needs to change direction. These factors make it much harder to blend design and implementation, to learn and iterate, or to make “small bets” that may be replicated or dropped.

Many DDD practices benefit from some amount of flexibility in funding. However, this can take many forms; completely unrestricted funds are not the only way to resource DDD approaches. Other examples include extended inception/design phases, dedicated funding for innovation and risk-taking, and triggering mechanisms for funding increases or other budget changes.

Examples

An extended inception period allowed the Three Millennium Development Goal project, in Myanmar’s Kayah State, to create a more context-specific and adaptable approach. Managed by the IRC and including six health organizations based in different ethnic communities, the project consortium used the six-month inception period to build trust through initial activities and conduct a stakeholder analysis. When the initial funding of $530,000 was expanded to a two-year grant for $8 million, the consortium had created specific plans for each health organization, based on the unique needs and capacities of their communities. There was also a flexible funding line, which was later tapped for opportunistic projects like a joint vaccination campaign run by multiple partners.

Flexible funding is also important for World Vision’s “Transformational Development” approach, which involves significant upfront community engagement prior to specific programs or grants. World Vision funds this work from unrestricted sources, especially through child sponsorship fundraising, and can then use grants for the projects that are identified through the process. This has enabled work with communities over longer time-frames than would be possible solely under grants. The organization is increasingly looking for ways to sustain the approach under shorter-term funding arrangements, especially in fragile contexts.

Insight : Adaptive partnerships go beyond budget lines

Even when funding is flexible—and especially when it is not—the way partners collaborate matters greatly in DDD approaches. Accountability mechanisms can stand in the way of program changes, as when pre-defined output measures cannot be changed to match program pivots, or when onerous compliance or reporting requirements take time and attention away from reflection and learning. On the other hand, partnerships characterized by open communication and sharing can actively encourage reflection, learning, and risk-taking.

approaches. Accountability mechanisms can stand in the way of program changes, as when pre-defined output measures cannot be changed to match program pivots, or when onerous compliance or reporting requirements take time and attention away from reflection and learning. On the other hand, partnerships characterized by open communication and sharing can actively encourage reflection, learning, and risk-taking.

These dynamics, between a donor and an INGO, are mirrored in the relationships among INGOs, sub-grantees, community-based organizations, communities, and other partners in a development initiative. Deep and ongoing engagement, as described above, often includes feedback/listening mechanisms that hold INGOs accountable to their partners and the communities they serve. Collaboration across organizations can bring scale to DDD efforts.

Examples

Though more focused on humanitarian relief, Mercy Corps’ South and Central Syria program illustrates the possibilities for adaptive partnerships, even in a challenging operating environment. In-country program partners, ranging from established local NGOs to more informal networks, would propose projects based on the needs they saw on the ground. The Mercy Corps team would work with them to craft context-appropriate compliance measures, so that they could access aid funding from major donors, and would also provide ongoing coaching to improve documentation over time.’

And then some sensible questions to finish off:

‘Localizing power and ownership in DDD practice: How might we link power shifts from the community level through to elite/ministerial levels, so that they reinforce one another? How can these links help to scale and sustain ownership?

Funding and accountability for adaptation: What types of flexible funding mechanisms, design and planning approaches, and partnership structures can best encourage collaborative DDD across agencies? And how do these vary by funding contexts, sectoral areas, and other factors?

Institutionalizing DDD across large agencies: What governance, administrative, operational, and other shifts need to happen in development institutions of all kinds to institutionalize of DDD approaches? How can voices and perspectives from the global south be valued in these shifts?’

Good to see INGOs coming to the table – I think the DDD movement will benefit greatly from their increased presence.

December 11, 2017

After 6 years and 100+ impact evaluations: what have we learned?

Longer projects don’t generate better results; women’s economic empowerment doesn’t seem to shift power  imbalances in the home. Just two intriguing findings from new ‘metanalyses’ of Oxfam’s work on the ground. Head of Programme Quality, impact evaluation champion and all-round ubergeek

Claire Hutchings

explains.

imbalances in the home. Just two intriguing findings from new ‘metanalyses’ of Oxfam’s work on the ground. Head of Programme Quality, impact evaluation champion and all-round ubergeek

Claire Hutchings

explains.

On this blog in 2011 we first shared our approach to ‘demonstrating effectiveness without bankrupting our NGO.’ A lot has happened in the last six years and we’ve hit a milestone this year. After 100 effectiveness reviews, we finally have enough impact evaluations to help us ask and credibly answer important questions across a portfolio of programme work. Or for the geeks amongst us: we’ve got meta-analyses!

Over the past few weeks be have begun publishing five separate meta-analyses (or three meta-analyses and two meta-syntheses for the pedants amongst us) on the Policy & Practice site, looking at evaluations of women’s empowerment, resilience, livelihoods and policy & governance interventions; as well as across our accountability reviews. Each will be accompanied by a blog on REALGEEK, diving into more detail on methodology and findings. Subscribe here if you don’t want to miss out, or read the first blog on women’s empowerment now.

I struggled to pull out the key insights to share (there are so many) – so I asked Karl Hughes, the original achitect of Oxfam GB’s Global Performance Framework (now Head of ICRAF’s Impact Unit, k.hughes@cgiar.org), what he’d most want to know, and then tried to answer:

What are they telling us about Oxfam GB’s overall effectiveness?

What are they telling us about Oxfam GB’s overall effectiveness?

While the findings from the individual studies were mixed, reassuringly they confirm an overall positive impact across all outcome areas. We looked to benchmark results against other organizations and were sometimes challenged by a lack of data for comparable interventions, or our bespoke measurement approach. That said:

In Sustainable Livelihoods programmes, we saw an average increase in incomes of 6.6%. This is good – though benchmarking isn’t totally straightforward, it is comparable with results from published independent reviews (for example, 6 recent RCTs of Ultra-poor “graduation” projects, or this systematic review of Agricultural certification schemes). For Women’s Empowerment and Resilience, where we use bespoke multi-dimensional indices that we’ve developed to conceptualise and measure these traditionally hard to measure outcomes, it’s harder to find external benchmarks. I’ve been warned (by Duncan, natch) against using technical terms like ‘standard deviation’, and despite best efforts, I’ve struggled to find ways to translate what we’ve found into ‘plain English’ (for a more technical intro to meta-analyses, you might want to check out ‘5 Key Things to Know About Meta-Analysis‘). Perhaps suffice to say that in both studies we see positive and significant impact. For women’s empowerment it is broadly in line with the literature on the impact of micro credit or self-help groups.

I’m by nature very cautious about making big claims – but I think the results reassure us that our programmes are having a positive effect on the things they’re trying to influence. This is the single most important recurring question that our staff, partners and supporters have – to know whether we’re making a difference – and for the first time we’re able to answer this across our portfolio of programme work, not just for individual projects and programmes.

How have all these studies contributed to learning and improving Oxfam’s practice?

We have some great examples of how individual Effectiveness Reviews have contributed to adaptations in  programme design – both our own programmes, but also a handful of powerful examples where the evidence they generate is being taking up by others. But Oxfam is limited in how much we can simply ‘scale lessons across’ a portfolio Because, rather than testing and adapting single intervention models, we work with partners, communities and individuals to design bespoke programming, grounded in a rights-based approach. Of course, there are transferrable lessons, but many useful insights are very context-specific. And we still suffer from knowledge management challenges. Documenting and storing information in accessible ways, and getting the incentives right for uptake and use are huge challenges in INGOs and beyond. But that’s a whole other blog post.

programme design – both our own programmes, but also a handful of powerful examples where the evidence they generate is being taking up by others. But Oxfam is limited in how much we can simply ‘scale lessons across’ a portfolio Because, rather than testing and adapting single intervention models, we work with partners, communities and individuals to design bespoke programming, grounded in a rights-based approach. Of course, there are transferrable lessons, but many useful insights are very context-specific. And we still suffer from knowledge management challenges. Documenting and storing information in accessible ways, and getting the incentives right for uptake and use are huge challenges in INGOs and beyond. But that’s a whole other blog post.

How much of the variation in results is down to different programming approaches and/or different contexts?

Perhaps most interestingly, some of our major assumptions aren’t born out in the results. For example, livelihoods and resilience meta-analyses found no evidence of a relationship between the duration of the projects evaluated and impact. This is surprising – as we might well assume that longer-term interventions will have better results. A likely explanation is that the duration of a project is closely related to the types of interventions carried out. For resilience for example, many of the shorter-term projects were focused on reducing vulnerability to natural hazards, whereas longer-term projects generally had more emphasis on strengthening the resilience of livelihoods activities, a longer-term endeavour for which the outcomes are less certain.

Similarly, our women’s empowerment meta-analysis confirms that increased access to income and/ or changes in the perceived role of women in the economy of their household or communities is not sufficient to change power dynamics within the household. Assumptions that there would be a spillover effect, and that this kind of work would de facto lead to change power dynamics within the household do not hold. If we want to support women to shift intra-household power dynamics, we need to target this explicitly.

We do see some regional variation, particularly in the meta-analysis of resilience interventions, and are exploring whether this is down to the nature of the shocks, differences in programming approaches or the measurement/ evaluation process itself.

We do see some regional variation, particularly in the meta-analysis of resilience interventions, and are exploring whether this is down to the nature of the shocks, differences in programming approaches or the measurement/ evaluation process itself.

This is a lot to digest – and we’ve only scratched the surface of the trends and patterns these studies are allowing us to pick up. We hope you’ll join us as we dive into the individual studies in a little more depth.

And a reminder that our Impact Evaluation Team is always looking to learn and improve our practice in a range of areas. We’re continuing to build measurement approaches for hard-to-measure outcomes, look for ways to strengthen both rigour and appropriateness of impact evaluation designs – and much more. Comments, constructive criticism, advice are always welcome – starting off in the comments section below, or reach out to me (chutchings@oxfam.org.uk) or Simone Lombardini (slombardini@oxfam.org.uk) who heads up our impact evaluation team.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers