Duncan Green's Blog, page 107

November 8, 2017

Is Recognition the missing piece of politics? A conversation with Francis Fukuyama

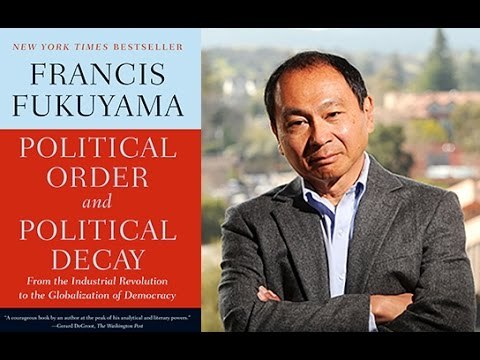

Getting Francis Fukuyama to endorse How Change Happens was one of the high points of publication – he’s been a hero of mine ever since I read (and reviewed) his magisterial history of the state (right). Last week I finally got to meet him, when I took up an invitation to speak to students and faculty at his Center for Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law (CDDRL) at Stanford.

hero of mine ever since I read (and reviewed) his magisterial history of the state (right). Last week I finally got to meet him, when I took up an invitation to speak to students and faculty at his Center for Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law (CDDRL) at Stanford.

I was anxious as hell, so read his 1992 book ‘The End of History and the Last Man’ on the plane over. This was based on a notorious 1989 essay, The End of History? Whenever you mention his name people who have never read anything he has written usually roll their eyes and say ‘you mean the end of history guy? Really?’ They are seriously losing out if they let that deter them from reading his work.

What struck me about the book was both how engaging it is (his writing is wonderful), but also how contemporary parts of it felt, a quarter of a century after publication. Not all of it though. ‘Liberal Democracy remains the only coherent political aspiration that spans different regions and cultures around the globe’ sounds very odd in these days of Trump, Brexit etc.

But the two forces he points to in order to justify that conclusion are worth thinking about. He portrays economics as driven by natural science, which is ‘cumulative and unidirectional’ and leads to the ‘progressive conquest of nature’.

The second force is ‘the struggle for recognition’. Plato in The Republic said there were three parts to the soul: desire, reason and recognition:

‘Desire induces men to seek things outside themselves, while reason or calculation shows them the best way to get them. But in addition, human beings seek recognition of their own worth…. The desire for recognition, and the accompanying emotions of anger, shame and pride, are parts of the human personality critical to political life. According to Hegel, they are what drives the whole historical process.

Recognition is the central problem of politics because it is the origin of tyranny, imperialism and the desire to dominate. But while it has a dark side, it cannot simply be abolished from political life, because it is simultaneously the psychological ground for political virtues like courage, public-spiritedness and justice.

Recognition is the central problem of politics because it is the origin of tyranny, imperialism and the desire to dominate. But while it has a dark side, it cannot simply be abolished from political life, because it is simultaneously the psychological ground for political virtues like courage, public-spiritedness and justice.

But is the recognition available to citizens of contemporary liberal democracy completely satisfying? The long term future of liberal democracy, and the alternatives that may one day arise, depend above all on the answer to this question.’

Fast forward 25 years and we discussed some of the consequences of this in his Stanford office:

What is the populist tide (Trump, Brexit etc) if not a backlash of the unrecognized – people who feel devalued and excluded from the circles of power and recognition? Sure enough, Fukuyama has a book on the politics of identity coming out in the spring, which builds on the central importance of recognition.

Much of the debate on automation and the future of work looks only through an economic lens – eg the advocates of a universal basic income as a substitute for labour if automation wipes out (and fails to replace) a large proportion of paid jobs. But that doesn’t address the fact that many people (especially men) seek recognition through their work. Hand waving about replacing that with everyone learning to enjoy their leisure and spend time with their kids doesn’t sound very thought through, especially when it comes to what replaces traditionally male jobs like driving as a source of recognition.

Our widening understanding of poverty is only just starting to incorporate aspects of recognition like shame, but that is likely to expand.

Always exciting when you meet a guru, and they turn out to be every bit as amazing as you’d hoped. His students are pretty extraordinary too – chatted to a team of Ukrainian movers and shakers who have come to Stanford to try and incubate a change strategy for their country. They’re there as part of CDDRL’s ‘Leadership Academy for Development’, which sounds like a lot of fun.

After I presented the book, his comment was that issues such as power analysis and systems thinking apply in multiple fields so ‘why not generalize this?’ – i.e. get out of the aid and development ghetto into fields such as public policy or labour rights. My answer, that I wanted to draw on personal experience and so had to stick to my knitting, didn’t satisfy either of us and he offered an enticing carrot. If I can come up with some de-aidified materials (paper, podcast etc) he would ‘proselytize the hell out of them’. Tempting.

November 7, 2017

Should the Gates Foundation Do Data Differently?

Spent a fascinating day last week talking to staff at the Gates Foundation at its HQ in a cold, grey and sleety Seattle (felt quite at  home). I presented the book in one of those ‘brownbag lunches’ that Americans love (although these days ‘clear plastic box lunches’ would be more accurate), and we then got on to discussing the implications for aid agencies in general and foundations in particular (here’s the slides from my presentation – foundation-relevant stuff at the end).

home). I presented the book in one of those ‘brownbag lunches’ that Americans love (although these days ‘clear plastic box lunches’ would be more accurate), and we then got on to discussing the implications for aid agencies in general and foundations in particular (here’s the slides from my presentation – foundation-relevant stuff at the end).

One big issue for them is data – how can they get the data that they and their partners collect to have more of an impact on policy discussions? I drew a comparison with other areas like governance, where people have realized that the kind of focus on supply side that we now see on data has failed to deliver the anticipated results – all those ‘capacity building’ workshops on good governance don’t amount to a revolution, apparently.

The governance people then moved on to work more on the demand side – let’s strengthen civil society to demand better governance (cue more workshops). More recently, they have gone into ‘convening and brokering’ mode (bringing together different, even mutually hostile actors to look for common solutions), along with ‘working with the grain’ of existing institutions, rather than just trying to implant alien institutions from elsewhere.

What might be the equivalent process on data, which in some ways is really just another institution?

On the demand side, we know that decision makers are influenced by ‘critical junctures’ – those moments when windows of opportunity open up, often linked to shocks and failures, and those in charge suddenly become open to new ideas to sort out the mess. But the supply side of data is remorselessly steady state and not geared up to respond to such moments. So how about setting up a rapid reaction unit that spots such opportunities, then mobilizes the data from Gates and elsewhere and gets it into the hands of the right people?

On the demand side, we know that decision makers are influenced by ‘critical junctures’ – those moments when windows of opportunity open up, often linked to shocks and failures, and those in charge suddenly become open to new ideas to sort out the mess. But the supply side of data is remorselessly steady state and not geared up to respond to such moments. So how about setting up a rapid reaction unit that spots such opportunities, then mobilizes the data from Gates and elsewhere and gets it into the hands of the right people?

And what’s the equivalent of ‘working with the grain’ when it comes to data – are there different kinds of locally data that are more deeply embedded in different societies than the standard universal metrics used by the international aid system? Would using that kind of data make it easier to influence policies and (maybe even more) social norms?

In passing, I also think the Foundation is slightly deluding itself when it swears allegiance to the unadulterated elixir of ‘evidence based policy making’, where evidence alone determines what governments do, and the nature of that evidence is heavily skewed towards statistical data (rather than, say, experience and judgement). Why? Because the Foundation’s own success illustrates that influence is often more about the messenger than the message – the fact that it is Bill and Melinda lobbying governments often matters as much or more than whether their message is data driven. So perhaps the Foundation should be more explicit about the importance of champions (and expand them beyond the Gateses – BMGF fellows dotted around the world? Evidence Elders?)

As for the equivalent of ‘convening and brokering’, how about hosting data surgeries, where the Foundation uses its convening power to persuade decision makers to present their thorniest problems, and a team of evidence geeks then help them identify what data could be of use in addressing them, and process it into a useable form. Is that already happening somewhere?

A couple of other ideas: select a dozen of the Foundation’s greatest hits – the iconic stories of success that every  institution tells itself – and go back and do a rigorous ‘how change happens’ study on each. That would reconstruct a timeline, identify the accidents and blind alleys, champions, blockers etc and come to a more nuanced view of the role of data in influencing policy, compared to other factors like messengers, chance and so on. See previous rant about the risks of airbrushing out all the messiness and politics in the stories we tell ourselves and others about social change.

institution tells itself – and go back and do a rigorous ‘how change happens’ study on each. That would reconstruct a timeline, identify the accidents and blind alleys, champions, blockers etc and come to a more nuanced view of the role of data in influencing policy, compared to other factors like messengers, chance and so on. See previous rant about the risks of airbrushing out all the messiness and politics in the stories we tell ourselves and others about social change.

One other exchange at the Brownbag was interesting – I was asked what to suggest when there was ‘no neat conceptual model’ for the kind of systems-driven, adaptive management approach I was advocating. My response: ‘well, actually there is a very good model – entrepreneurs’. Can’t believe I ended up telling the Gates Foundation to learn from entrepreneurs! What is interesting is that the way they behave often bears little relation to the kinds of procedures even the Gates Foundation demands: I suggested they ask Bill to submit Microsoft’s strategy circa 1980 to see if it would have qualified for a Gates grant…..

Over to any of the Gates people who were present to set me straight or add their bit.

November 6, 2017

What kind of evidence might persuade people to change their minds on refugees?

Oxfam Humanitarian Policy Adviser Ed Cairns reflects on using evidence to influence the treatment of refugees

Who thinks that governments decide what to do on refugees after carefully considering the evidence? Not many, I suspect. So it was an interesting to be asked to talk about that at the ‘Evidence for Influencing’ conference Duncan wrote about last week.

When I think what influences refugee policy, I’m reminded of a meeting I had in Whitehall on Friday 4 September, two days after the three-year-old Syrian boy, , had drowned. Oxfam and other NGOs had been invited in to talk about refugees. The UK officials found out what their policy was by watching Prime Minister David Cameron on their phones, as he overturned the UK’s refusal to resettle thousands of Syrians in a press conference in Lisbon. Even then, he and his officials refused to promise how many Syrians would be allowed. By Monday, that line had crumbled as well, and a promise of 20,000 by 2020 was announced.

The evidence of course had shown that children and other refugees had been tragically drowning in the Mediterranean for months. But it was the sheer human emotion, the public interest, and no doubt Cameron’s own compassion that made the change. Evidence and the evidence-informed discussion between officials and NGOs had nothing to do with it. More important was that a single image of a drowned boy spread to 20 million screens within 12 hours as #refugeeswelcome began trending worldwide. As research by the Visual Social Media Lab at the University of Sheffield set out, “a single image transformed the debate”.

Two years later, a new Observatory of Public Attitudes to Migration has just been launched by the Florence-based Migration Policy Centre and its partners, including IPSOS Mori in the UK. It aims to be the ‘go-to centre for researchers and practitioners’, and has sobering news for anyone who thinks that evidence has a huge influence on this issue. Anti-migrant views, it shows, are far more driven by the values of tradition, conformity and security, and within the UK in particular, according to an IPSOS Mori study, by a distrust of experts, alongside suspicion of diversity, human rights and “political correctness”.

Two years later, a new Observatory of Public Attitudes to Migration has just been launched by the Florence-based Migration Policy Centre and its partners, including IPSOS Mori in the UK. It aims to be the ‘go-to centre for researchers and practitioners’, and has sobering news for anyone who thinks that evidence has a huge influence on this issue. Anti-migrant views, it shows, are far more driven by the values of tradition, conformity and security, and within the UK in particular, according to an IPSOS Mori study, by a distrust of experts, alongside suspicion of diversity, human rights and “political correctness”.

I’m no expert on refugee or migration policy, though like a lot of Oxfam old-timers I have seen for decades how the poorest countries in the world host more refugees than most European countries could even dream of. But when I talk to colleagues working on Oxfam’s European migration response, I hear something very like what the Observatory is saying. “Facts confirm bias, or get challenged or ignored,” was the pithy comment of Claire Seaward, who runs Oxfam’s European migration campaign. And when NGOs from across Europe gathered this year at a conference on Communicating on Refugee and Migrant Issues, they heard of the power of emotion more than evidence, including from the research group Counterpoint, which pointed out that the vast majority of human thought is emotional, automatic and associative, and that we all accept falsehoods if they fit our existing views.

This isn’t just about attitudes to refugees and migrants, though perhaps they are a particularly emotive issue. Nor is it just about the woman or man ‘in the street’, while politicians consider evidence carefully. As an article in the British Journal of Political Science this August, ‘The Role of Evidence in Politics’, suggested, “politicians are biased by prior attitudes when interpreting information,” and new evidence may reinforce, not influence, those attitudes. Actually this was based on a study in Denmark, not the UK, but British readers can probably imagine what it meant.

So where does this leave NGOs trying to influence policy or public attitudes on refugees? To paraphrase Bill Clinton, “it’s the emotion, stupid”, that matters; or at least that’s the tone of quite a lot of NGO thinking as we try to communicate more effectively in difficult times. But Oxfam’s experience shows that it’s wrong to think that emotion and evidence are opposing choices.

Last year, as we began our “Stand As One” campaign on refugees, we published two pretty straightforward examples  of “killer facts” – compelling figures to grab public attention. The first showed that the world’s 6 wealthiest nations, which made up more half of the global economy, hosted less than 9 per cent of the world’s refugees and asylum seekers. In contrast, half the world’s refugees and asylum seekers were hosted by countries such as Jordan and Pakistan, that collectively accounted for less than 2 per cent of the global economy.

of “killer facts” – compelling figures to grab public attention. The first showed that the world’s 6 wealthiest nations, which made up more half of the global economy, hosted less than 9 per cent of the world’s refugees and asylum seekers. In contrast, half the world’s refugees and asylum seekers were hosted by countries such as Jordan and Pakistan, that collectively accounted for less than 2 per cent of the global economy.

The second showed that, for all the attention on Alan Kurdi’s death, the number of global refugee and migrant deaths went up by more than a fifth in the following year. Both these slim briefings had the same objective, to put Oxfam’s message in the minds of people we would be talking to soon, because the life of a “killer fact” is not long. (Alright, 8 men own the same wealth as half of humanity is an exception.) In July 2016, that was the hundreds of thousands of people going to the UK’s summer festivals, one of the main ways we were trying to promote a petition. In September, it was the diplomats meeting at summits on refugees and migrants in New York.

Both examples were new calculations using existing data, from UNHCR, the World Bank, and the International Organization for Migration, choosing data that would stir emotions, particularly in the case of deaths that rekindled memories of Alan Kurdi.

Both were inexpensive in staff time and had no other costs – not an irrelevant point as we try to work out what research has the most influence. Apart from Oxfam’s media output using celebrities, they had more media coverage in the UK than any of our other output in 2016 about refugees. Anecdotally at least, they did indeed help create a fertile climate to speak with festival-goers and high-flying diplomats alike.

That type of research is useful, of course, but also limited. Does it transform attitudes in the long-term? Does it influence people who don’t already agree with our views? I don’t think so. It feels like an approach that is talking to the 24% of people in the UK who are “open to immigration”, but perhaps not much to the 48% that are in “mid-groups” according to IPSOS Mori, and who are potentially open to the kind of genuine argument, rather than rallying the converted, that NGOs are not so good at.

That type of research is useful, of course, but also limited. Does it transform attitudes in the long-term? Does it influence people who don’t already agree with our views? I don’t think so. It feels like an approach that is talking to the 24% of people in the UK who are “open to immigration”, but perhaps not much to the 48% that are in “mid-groups” according to IPSOS Mori, and who are potentially open to the kind of genuine argument, rather than rallying the converted, that NGOs are not so good at.

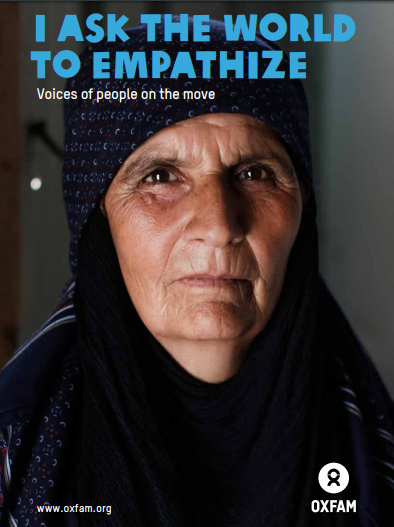

Our second approach to use evidence in the “Stand As One” campaign was also useful but limited. That’s when we combined personal case stories with policy options or recommendations. A perfect example is a paper we published with the British Red Cross, Refugee Council and Amnesty International this February. Together Again presented seven cases to illustrate why particular policy suggestions would make sense. Tesfa, a teenage refugee in the UK, for instance, was separated from his mother and younger siblings because the UK does not allow refugees under 18 to apply for their families to join them from abroad. I Ask the World to Empathize took a similar approach, and was widely welcomed by already-interested diplomats in New York where it was mainly used. But does that kind of research speak to anyone who does not empathize with refugees already? I somehow doubt it.

Our third approach is a more innovative and ambitious attempt, which my colleague, Franziska Mager, presented to the ‘Evidence for Influencing’ conference. She has used , a narrative-base method for collecting quantitative and qualitative data, initially in the Central African Republic. It involves asking displaced people to tell a story about a specific experience related to their decision making whilst in limbo, and then, through an intricate follow up questionnaire, to interpret through the respondents’ eyes what they find most significant. We’ll be publishing the results in the next few months, when we hope we will see how, when cleverly combined, the power of stories and of stats can work together to make a convincing argument.

But perhaps all these approaches have a common limit, when it comes to using them for influencing. Do they all speak to readers who, like their writers and researchers, believe in the value of universal human rights? The IPSOS Mori and other studies have shown that they – we – are no more than 20% or 25% of the population. Without influencing others, NGOs may hope for the odd success, such as seizing the moment to influence a Prime Minister to change one policy. But if NGOs are really going to help transform attitudes and eventually policy on refugees and migrants, it’s going to take not only a generation, but evidence that speaks to at least some of the “mid-groups” that are not convinced by NGOs’ traditional messages.

speak to readers who, like their writers and researchers, believe in the value of universal human rights? The IPSOS Mori and other studies have shown that they – we – are no more than 20% or 25% of the population. Without influencing others, NGOs may hope for the odd success, such as seizing the moment to influence a Prime Minister to change one policy. But if NGOs are really going to help transform attitudes and eventually policy on refugees and migrants, it’s going to take not only a generation, but evidence that speaks to at least some of the “mid-groups” that are not convinced by NGOs’ traditional messages.

This takes us to one final research approach that we’re exploring now. We will find out if it works when we publish in 2018. With the Refugee Council, we’re exploring the experiences of a number of refugees in the UK, and in particular whether their experiences of the UK’s system of family reunification has had an effect on their ability to fit into British society. That in itself is a vital issue, but it’s also an issue which speaks not only to readers driven by universal human rights, but also to readers driven more by concerns for social cohesion in the UK.

That research is not quite finished, but what’s exciting about it, I hope, is that it’s providing evidence, and powerful human stories, not only for a traditional NGO narrative to uphold human rights – though it absolutely is. But it also fits a narrative that a far wider number of people already believe in –building social cohesion in a disunited Britain. And it brings those two things together in an inclusive narrative – that the UK should allow refugee families to live together in the UK, because that would be right and humane, and because it would help make the UK a more cohesive place as well.

Will that influence anyone? We’ll see. If it helps persuade a handful of MPs to change the UK’s family reunion policies, that will be worthwhile. But perhaps, just perhaps, it could be an example to follow in the future – generating evidence for inclusive narratives that could appeal beyond NGOs’ traditional supporters.

November 5, 2017

Links I Liked

The power of league tables to incentivise behaviour change (see right).

If you’re in Canada, check out this week’s speaking tour (me + Shirley Pryce, President of the Jamaica Household Workers Union (JHWU), Julie Delahanty, Executive Director of Oxfam Canada, and local women’s rights activists)

Find Out Some (But Not All) The Secrets of China’s Foreign Aid

The reverse advent calendar. One item per day in a hamper, take it to a foodbank on/around 25th December.

Hooray! WTF Friday is back by popular demand, and because the inimitable Wronging Rights has lots to be grouchy about.

The new BRIGHT magazine for rigorous-but-positive ‘solutions journalism’ looks interesting.

I don’t understand emojis (& most of the time can’t even see them – too small), but I’m sure they’re a step backwards. Bah Humbug.

David Booth on Revisiting the developmental state: towards ‘developmental regimes’ in Africa?

Not quite sure what to make of this. Clever subversion of the patriarchy or reinforcing the sexist frame? Instead of stating their body measurements, contestants in this beauty pageant listed statistics about violence against women in Peru (but the backdrop shows it was orchestrated, not rebellion).

November 3, 2017

Is there a new Washington Consensus? An analysis of five World Development Reports.

Alice Evans earns my undying admiration (and ubergeek status) by casually revealing that she has read the last 5  WDRs on the day of their publication. Here she summarizes what they show about the Bank’s evolving view of the world.

WDRs on the day of their publication. Here she summarizes what they show about the Bank’s evolving view of the world.

A new Washington Consensus is emerging… It recognises complexity, context, learning by doing, politics, and ideas. Hitherto fringe perspectives have become mainstream – embraced by successive World Development Reports (WDRs). But what’s missing, and what still needs to be debated?

Given the WDRs’ substantial research budgets, widespread dissemination, and legitimacy, they shape the scope and nature of debates within the development community. I read each one on the day of publication. It’s a tradition of mine – like Christmas, but with infographics instead of crackers. Reflecting on the last four years, I see a pattern emerging.

Rejecting ‘best practice’, the World Bank now champions learning by doing, experimenting in country and iteratively adapting. That signals a major departure from homogenous, externally approved Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers. Though we’d need to research if this ambition is reflected in a shift in World Bank project management.

“Problem-driven iterative adaptation drives successful reforms” – from WDR2018.

Recent WDRs also emphasise politics: policy recommendations may not be heeded by actors with divergent interests. Desire to placate donors may yield ‘isomorphic mimicry’: the façade but not function of good governance. So, the Bank commends ‘working with the grain’; engaging with elite interests and ideologies; addressing collective action problems; building support for reform through inclusive dialogue.

This is excellent, legitimising a wider consensus. But I still have a couple of questions…

This is excellent, legitimising a wider consensus. But I still have a couple of questions…

“Three institutional functions – commitment, coordination, and cooperation – are essential to the effectiveness of policies” – WDR2017.

First, governments’ policy experiments are likely to reflect their priorities. For example, most Bangladeshi politicians are also garment factory owners – with vested interests in protecting business autonomy, curtailing state regulation, repressing labour, and restraining wage hikes. The WDRs may authorise experimentation, but perhaps wider political shifts are needed to motivate pro-poor experimentation?

The other HUGE elephant in the room is social movements. WDR2018 on Education mentions reforms in Chile, but omits widespread student protests. WDR2016 on ICTs focuses on external interventions and individual service users; neglecting how they might strengthen social movements. Likewise, WDR2015 on Mind, Society and Behaviour omits how collective organising has enabled poor and marginalised groups to gain self-esteem, reject pejorative stereotypes, critique inequalities, build solidarity, and catalyse government commitment to inclusive growth. Disregarding history, blinkered to indigenous protests, pretending there’s a peaceful pathway to all things good, WDR2015 exclusively refers to short-term ‘antipoverty policies and programs’, such as ‘self-esteem talks’ in Peru….?!

People march to demand free, quality public education in Chile (7/8/2011).

Finally, what about international inequalities, rich countries and global governance? The WDRs largely focus on low and middle income countries (LMICs), and the problems therein. For example, WDR2013 on Jobs explores how LMIC governments can strengthen private-sector led growth and job-creation. Recognising that working conditions in global production networks are rarely improved by voluntary corporate codes of conduct, the WDR2013 calls on LMIC governments to strengthen legal protections and improve compliance in country. This is important, of course. But it neglects these governments’ incentives to repress wages to attract global buyers.

Why this lacuna? Maybe it reflects Western dominance in the World Bank, groupthink, and resistance to self-critique? Perhaps it’s asymmetric confidence: widespread pessimism that we can change our own institutions, yet perennial optimism that reform is possible ‘over there’, if only we get the policies/ institutions/ politics right? Or maybe the World Bank assumes it only has influence in LMICs (not the UK, US and Germany), because it only provides financial support to the former? Here the Bank may be underestimating its influence. By focusing on reforms in LMICs, I fear that the WDRs narrow debates within the international development community, distracting attention from the need for rich countries to strengthen their commitment to global development.

So, in sum, it’s fantastic the WDRs champion politically smart, locally led iterative adaption and inclusive coalitions. But we also need to recognise the power of social movements (shifting norms, showcasing widespread resistance), and get our own houses in order.

Acknowledgements: I am very grateful to the wonderful David Evans, who provided astute comments on an earlier draft.

And for those who want to dig deeper, here is the previous FP2P coverage of WDR 2018 (education), WDR 2017 (governance and law), WDR 2016 (digital), WDR 2015 (mind and culture) and WDR 2013 (jobs). Must have been asleep when WDR 2014 (on risk) came out.

November 2, 2017

Is inequality going up or down?

My Oxfam colleague and regular FP2P contributor Max Lawson sends out a weekly summary of his reading on  inequality (he leads Oxfam’s advocacy work on it). They’re great, and Max has opened his mailing list up to the anyone who’s interested – just email max.lawson@oxfam.org, with ‘subscribe’ in the subject line.

inequality (he leads Oxfam’s advocacy work on it). They’re great, and Max has opened his mailing list up to the anyone who’s interested – just email max.lawson@oxfam.org, with ‘subscribe’ in the subject line.

Here’s his latest effort – a long, but excellent overview on the latest debates and data on inequality.

‘You would think a question like ‘Is inequality going up or down?’ would be relatively easy to answer, but sadly it is not. At Oxfam we have identified the growing gap between rich and poor and the impact of high inequality as a serious crisis. But how serious is it really?

The poverty and inequality of data on inequality

The first thing to say is that the data is not good, but that we do know that the problem is strongly biased in one direction – inequality is systematically underestimated. We also know the data for developing countries is much worse than that for rich nations. The main method used is to calculate a country’s Gini coefficient (a number between 0 and 1, where 1 is perfect inequality and 0 is perfect equality). The Gini has been criticised, and other measures like the Palma which look at ratio between the top 10% and the bottom 40% are favoured by many. Nevertheless, it remains the most widely accepted measure.

The Gini is calculated using household surveys or census data. This data has been shown to systematically underestimate the incomes of the richest part of society. For example, a [found that the richest survey respondent had a salary lower than that of a manager in a typical medium-to-large scale firm. The super-rich do not fill out surveys, and when they do they rarely reveal the true scale of their income.

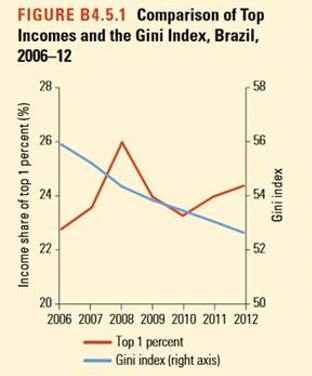

Various methods are being pioneered to recalculate top incomes, to complement the surveys, most famously the and a group of economists behind the World Incomes Database. Another way is supplementing national accounts data for survey data. These methods, whilst themselves far from perfect, demonstrate in every country that inequality is worse than previously thought. They also have an impact on trends. Using top incomes, Brazil has not reduced inequality whereas it has if we look at the Gini.

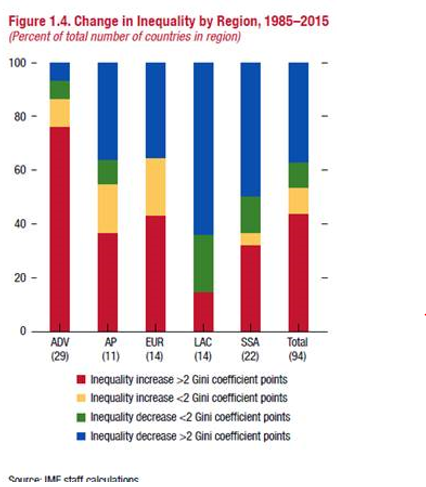

source: World Bank Poverty and Shared Prosperity Report 2016 page 80

Global Income Inequality Going Down

The thing that is measured most commonly is income inequality, the gap in the incomes between the richest and the poorest.

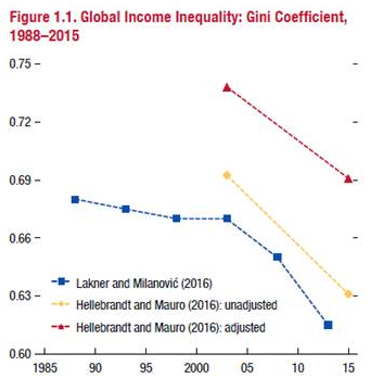

The good news is that global income inequality is very likely to be falling. If everyone on earth were the citizen of one country, then the gap between the richest and the poorest has reduced. Christoph Lakner and Branko Milanovic have pioneered work in this area, and Branko recently wrote an excellent blog on this. The fall in inequality is the result of growing incomes in the developing world, and particularly in China. It remains extremely high, however. If the world were a country, it would have inequality levels around about the same as South Africa, one of the most unequal countries in the world.

Source: IMF Fiscal Monitor October 2017 page 3

Within-country income inequality

Arguably what matters to moxst people though is the income gap between rich and poor in their own country. So what has been happening here?

Using the best data available, the IMF in their excellent Fiscal Monitor released recently, try to look at how income inequality has increased or decreased in as many countries as possible – 94. They conclude that inequality has increased in the majority of the 94 countries they were able to look at over the last thirty years, but only just – 53% of them.

Source: IMF Fiscal Monitor October 2017 page 4

The regional variation is interesting. In Latin America, it rose fast for the first twenty years, and then fell in many countries for the last ten, as governments took strong steps to reduce inequality. In Asia it is the reverse, with equitable growth nearer the start of this period changing into a big increase in inequality in recent years. In most (but not all) rich countries inequality has risen quite sharply, although at different times during those thirty years. In sub-Saharan Africa, the picture is mixed. For the Middle East and North Africa, the data is simply not available.

The countries that have seen rises in inequality include China and India, and some of the other countries with the biggest populations. This means that seven out of ten human beings live in a country where inequality has risen in the last thirty years. China’s inequality has reduced slightly in recent years, but remains almost twice as high as it was thirty years ago.

The IMF conclusions, which are similar to the , are important. They reflect a lot of what we know already about the great efforts made in Latin America to reduce inequality, through more progressive taxation and more progressive spending. These efforts are now being threatened by a wave of new right-wing governments that are opposed to such action.

They also show that the picture is mixed in other parts of the world too, and this is also reflected in Oxfam’s , which highlights those countries in other regions, like Namibia, that have made significant efforts to reduce inequality.

These good news stories are important, as we need to learn from them and use them to pressure the many governments that are doing the wrong thing.

Taxing and spending is not the full story though. Other countries like Cambodia have seen significant decreases in inequality because of the pro-poor nature of their growth, rather than any significant active intervention by government using tax or spending. This shows the crucial importance of growth that creates good jobs for those at the bottom of society.

It also shows the paucity of data. In the IMF work, comparisons are only possible for 94 countries. Less than half of sub-Saharan African countries are covered, and only 11 countries in Asia and the Pacific.

Consumption versus income

There is another crucial distinction in how income Gini coefficients are measured. In Latin America and rich countries, they are based on income; in Africa and Asia on consumption (as a proxy for income). Consumption Gini coefficients are generally much lower, so comparing Africa and Asia with Latin America is to confuse apples with oranges. This is important, but rarely noticed. India for example has a consumption Gini (the official one) which is similar to Ireland’s. Its income Gini is much higher, similar to Brazil’s. Whilst this does not affect the observation of trends over time in individual countries or regions, it does make global comparisons rather specious.

Wealth inequality

The other major measure of the gap between rich and poor is wealth, rather than income. Here the data is even worse. But again, we know with some certainty that wealth inequality is systematically higher than income inequality.

Wealth inequality is very important because it is wealth that links most closely to political power and influence, not income. Today’s income inequality also becomes tomorrow’s wealth inequality, as the value of wealth rises more rapidly than incomes. This is compounded by inheritance.

The best data on global wealth trends is the work by Credit Suisse in . It is this data that we use to produce our ahead of Davos each year. Data on the wealth of those at the bottom of society are not available for many countries to a decent standard, including most developing countries.

In terms of trends, it is clear from what we know that wealth inequality has risen considerably in recent decades in many countries. The wealth in the hands of the top 10% in China is now similar to that observed in the US. We also know that the wealth of the top 1% has increased, and is now higher than the whole of the bottom 99% of humanity.

Rich countries and developing countries

The basic level of inequality is significantly higher for almost all developing countries, than for rich countries. This in turn is linked to the much greater levels of redistribution that rich countries engage in. The IMF fiscal monitor points out that more than three quarters of the difference in income inequality between rich countries and Latin American countries is explained by the differences in the levels of taxation and spending.

We also know from other IMF work, that a Gini coefficient above 0.27 has been found to be harmful to growth. Only 11 countries in the world have inequality lower than this, and a number of developing countries have inequality almost twice that level.

We also know that high levels of income and wealth inequality have been linked to a large range of negative social and political outcomes. They also make it much harder to reduce poverty, as the majority of income growth is captured by those at the top.

Absolute inequality versus relative inequality

There is one final measure that deserves mention. All these other measures are relative- they measure the percentage increase for different groups in the population. So if I am poor and I get a 10% increase and the rich get a 10% increase, then relative inequality remains the same.

But if I am on ten dollars a day, and I get a ten percent increase, that is 1 dollar. If I am on 1000 dollars a day, and I get a ten percent increase, that is 100 dollars, or one hundred times as much. So absolute inequality increases. This is arguably more important, in terms of people’s spending power, and in terms of how they perceive inequality, which is much more likely to be in absolute terms- they see how much more money they have to spend, and compare that to how much more the rich have.

Oxfam has that whilst the relative/ percentage income increase for those towards the bottom and middle of the global income distribution compared well over the last thirty years with the percentage increase of those at the top (represented in the famous ‘Elephant Graph’ where the back of the elephant is the growth in the incomes of the relatively poor in the last thirty years, and the trunk the growth in the incomes of the richest,) the absolute increases are almost entirely captured by the ‘trunk’, and the back of the elephant disappears.

Source: Oxfam: http://oxfamblogs.org/fp2p/whats-happ...

So what can we conclude from all this?

1. It is good thing that global income inequality has reduced, but it remains very high indeed.

2. Global wealth inequality has increased. Wealth inequality levels are systematically higher than income inequality.

3. The majority of countries have seen an increase in income inequality in the last three decades, with sharp increases in the most populated countries.

4. A number of countries, especially in Latin America have seen a significant decrease and we need to learn from this.

5. Levels of income and wealth inequality are far too high in almost every country, and especially in developing countries, threatening growth, poverty reduction and driving a range of negative social and political outcomes.

6. Data on inequality is very poor, and systematically underestimates the incomes and wealth of the rich, and with this the scale of the problem.

7. Absolute levels of inequality remain dramatic, with the vast majority of global income growth being captured by the top 10%, and the top 1% capturing more than the bottom 50%.’

October 31, 2017

How is evidence actually used in policy-making? A new framework from a global DFID programme

Guest post from

David Rinnert

(@DRinnert) and

Liz Brower

(@liz_brower1), both of DFID

Guest post from

David Rinnert

(@DRinnert) and

Liz Brower

(@liz_brower1), both of DFID

Over the last decade there has been significant investment in high-quality, policy-relevant research and evidence focussed on poverty reduction. For example, the American Economic Association’s registry for randomised controlled trials currently lists 1,294 studies in 106 countries, many of which have yielded insights directly relevant to the SDGs; there is an even larger number of qualitative evaluations and research on development interventions out there. However, as shown again and again (including on this blog), the generation of relevant evidence alone does not lead to improved development outcomes. In many countries and sectors, lack of demand for and use of evidence by decision-makers remains an issue. Policymakers, especially at lower levels, are not rewarded for innovation, and they lack the capacity and/or incentives to use evidence for decisions.

The UK Department for International Development (DFID) designed the Building Capacity to Use Research Evidence (BCURE) programme in 2013 to address this issue across 12 countries. Over the past four years, BCURE has promoted the use of evidence by decision makers, which has contributed to improved development outcomes and has generated many lessons on what works and what doesn’t in the promotion of evidence uptake. However, a key question for BCURE partners has been how to think more precisely about the increased use of evidence as an improved development measure, and how policymakers, researchers and practitioners should value the impact generated and communicate this in an effective way. There is a substantial body of literature discussing the value of research and evidence products (for example see here, here and here, or here on FP2P); however there has been less  focus on unpacking and valuing evidence use. Building on existing literature and experience from the programme, BCURE has developed a typology for the type of evidence use by policymakers, namely: Transparent Use, Embedded Use and Instrumental Use, as defined in the table below. The framework can be used to capture the range of uses of evidence and offers a starting point for recording and comparing value through the avenues: scope, depth and sustainability.

focus on unpacking and valuing evidence use. Building on existing literature and experience from the programme, BCURE has developed a typology for the type of evidence use by policymakers, namely: Transparent Use, Embedded Use and Instrumental Use, as defined in the table below. The framework can be used to capture the range of uses of evidence and offers a starting point for recording and comparing value through the avenues: scope, depth and sustainability.

Figure 1: BCURE Value of Evidence Use Framework

Transparent Use

Embedded Use

Instrumental Use

Description

Increased understanding and transparent use of (bodies of) evidence by policymakers.

No direct action is taken as a result of the evidence, but use of evidence becomes embedded in processes, systems and working culture.

Knowledge from robust evidence is used directly to inform policy or programme.

Examples

BCURE VakaYiko: Several roundtables were held to help bridge the gap between research and policy making on climate change in Kenya and to help decision-makers acknowledge the full body of evidence on climate change in the country.

BCURE Harvard: the researchers worked directly with government technicians to create a Report Dashboard designed to serve as a one-stop shop for over 50 indicators deemed crucial for evaluating MGNREGA.

BCURE University of Johannesburg: In South Africa the evidence map, published by DPME, fed directly into the decision-making of the White Paper on Human Settlements.

Scope: The array of policymakers impacted by the reform – is its impact far reaching across actors?

+++ inter government, policy teams and country offices

+ One local government ministry

+++ national level policy

Depth: Impact of change, how large is the size of the reform (for instrumental use it could eg be population reached)? Is there a substantial change from previous practice?

+ No in-depth change in practice that would be directly attributable to BCURE but contribution to a set of follow up actions

++ Evidence tool created and saw immediate use, 150,000 hits in the first year.

++ (tbc) The Human Settlements Policy is potentially reaching a large proportion of the population, however, overall effect is yet to be determined based on M&E results

Sustainability: How sustainable is the change in the use of evidence?

+ One-off meetings but with potential to influence further changes in the use of evidence

++Evidence suggests this will be a prolonged change

++ Evidence used for several policy decisions with potential to influence further policy choices

One example of value created from evidence use comes from India. A BCURE implementing organisation – Evidence for Policy Design at Harvard Kennedy School – saw that the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) was producing vast amounts of data that could be used to monitor programme performance and spur improvements, but that, in reality, ended up sitting in an unused website database. With BCURE funding, the researchers worked directly with government technicians to create a Report Dashboard designed to serve as a one-stop shop for over 50 indicators deemed crucial for evaluating MGNREGA, an example of value generated through Embedded Use as illustrated above (full case study here). This tool saw wide instrumental use as well: over 150,000 hits by over 100,000 users in the year following the launch.

In South Africa, the University of Johannesburg through BCURE worked with the Department for Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation (DPME) to develop a policy-relevant evidence mapping tool. The evidence map offered the department visual and easy access to evidence. Other policy stakeholders benefited from the lessons learnt from the pilot evidence map – an example of Embedded Use discussed in the table. A range of public sector actors were invited to engage with the methodology (Transparent Use). The evidence map, hosted by DPME, fed directly into the decision-making of a White Paper on Human Settlements, an example of Instrumental Use of evidence.

While many BCURE projects achieved positive development outcomes, even the less successful pilots have helped  unpack some of the main challenges and barriers to evidence use. One of the key lessons is that we need to better understand politics and incentive structures in government organisations when promoting evidence uptake. Even if individual or organisational capacity exists, evidence may remain unused if groups with sufficient bargaining power lack incentives to improve policy outcomes. Promoting the use of evidence thus requires an in-depth understanding of the political economy, and a politically savvy implementation approach. Furthermore, BCURE was more successful where it helped coordinate between the often large amount of existing research organisations and projects, rather than creating new structures or mechanisms.

unpack some of the main challenges and barriers to evidence use. One of the key lessons is that we need to better understand politics and incentive structures in government organisations when promoting evidence uptake. Even if individual or organisational capacity exists, evidence may remain unused if groups with sufficient bargaining power lack incentives to improve policy outcomes. Promoting the use of evidence thus requires an in-depth understanding of the political economy, and a politically savvy implementation approach. Furthermore, BCURE was more successful where it helped coordinate between the often large amount of existing research organisations and projects, rather than creating new structures or mechanisms.

The examples and lessons from BCURE illustrate the variety of ways in which we can support the use of evidence by policymakers, and how this in turn can contribute to improved development outcomes. Our framework broadens the focus of evidence use above and beyond ‘instrumental use’, and lessons from this work highlight the importance of thinking and working politically in this area.

We would love to hear from other organisations on how they are tackling the evidence use puzzle. What else could and should be done to get more research and evidence into action in development?

David Rinnert is an Evaluation Adviser and Evidence Broker with the UK Department for International Development (DFID). Liz Brower is an Assistant Economist with DFID. The views expressed in this blog do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies.

All reports, learning documents and other resources from BCURE can be found here.

October 30, 2017

Links I Liked

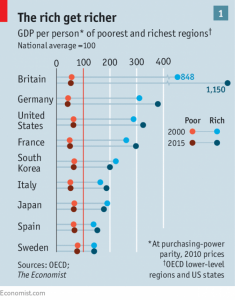

The rich are getting richer; the poor not so much. Japan, South Korea are the exceptions. H/t The Economist

Last week was ‘Open Access Week’ and there’s some good news: The number and proportion of freely available articles is growing; reaching 45% of the literature published in 2015

Influencing for social justice: nudge, shove, show or shout? New Oxfam blog series on advocacy

Brilliant from Lant Pritchett: why aid’s obsession with attribution risks undermining the team sport of development

Emergency sexwork: should NGOs recognize transactional sex as a livelihood strategy? My LSE colleague Thea Hilhorst rattles a few cages on the new ISS blog

The death and life of liberation theology – should be required reading for young activists.

Next week is Living Wage Week so Citizens UK rated English Premier League soccer clubs’ performance. Not impressed – despite collective £3.6bn turnover, only two clubs pay their staff the living wage.

October 29, 2017

Is it time to get personal on tax dodging?

The people who read this blog tend to be rationalists and progressive, so they won’t need much convincing that  tax avoidance is a big (and lethal) deal. Oxfam calculates that just a third of the $100bn [approx. £78bn] tax that companies dodge in poor countries annually is enough to cover the bill for essential healthcare (vaccinations, midwives and diarrhoea treatment) that could prevent the needless deaths of eight million mothers, babies and children.

tax avoidance is a big (and lethal) deal. Oxfam calculates that just a third of the $100bn [approx. £78bn] tax that companies dodge in poor countries annually is enough to cover the bill for essential healthcare (vaccinations, midwives and diarrhoea treatment) that could prevent the needless deaths of eight million mothers, babies and children.

But we’ve been putting out these kinds of ‘killer facts’ for years, and our market research suggests that tax remains an issue that fails to move the public – too geeky; too remote. It shows the limits to the kinds of evidence-based narratives we were discussing in the Netherlands last week. (Ed Cairns will have more on that later this week).

So we decided to try and humanize the issue, asking the Don’t Panic Creative Agency that produced the award-winning Syria video for Save the Children to come up with something that would make tax avoidance an urgent, human issue that ‘cuts through’ to the non-wonk world. Here’s what they came up with: ‘The Heist No One is Talking About’. What do you think?

If you like it, please tweet the link, embed the video or go to the Even It Up campaign website for ideas on how to get involved. FAQs on the film here.

And if you prefer your evidence less personal and upsetting, here you go (from the press release accompanying the film).

‘Oxfam is urging the Chancellor to use next month’s Budget to commit to implementing tougher tax laws for British multinationals, including those that operate in developing countries, by the end of 2019. As movement towards an EU tax transparency deal has stalled, it is calling on him to push ahead and build on the leadership some UK companies have already shown.

More than a year since the Government passed legislation to enable the introduction of comprehensive public country by country reporting for UK-based companies and nearly two years since the last Conservative government agreed the case had been made for the change, it is still no closer to being a reality.

The authors of ‘Advancing social and economic development by investing in women’s and children’s health: a new Global Investment Framework’, which draws on the work of a group coordinated by the WHO and The Partnership for Maternal, Newborn & Child Health, estimate that 147m child deaths, 32m stillbirths and 5m maternal deaths could be avoided if health expenditures increased by US$5 per capita per year between 2013 and 2035. The report examines 74 countries with large numbers of people living in poverty which experience 95 percent of global maternal and child mortality, such as India and Zambia. Oxfam’s figures are annual averages based on the aggregate numbers i.e. a total spend of $678.1bn, or $29.48bn a year over 23 years, to prevent 7.78m child deaths and 217,000 maternal deaths annually.

examines 74 countries with large numbers of people living in poverty which experience 95 percent of global maternal and child mortality, such as India and Zambia. Oxfam’s figures are annual averages based on the aggregate numbers i.e. a total spend of $678.1bn, or $29.48bn a year over 23 years, to prevent 7.78m child deaths and 217,000 maternal deaths annually.

The UN estimates that corporate tax avoidance costs developing countries at least $100bn a year, i.e. $8.3bn a month and $33.3bn every four months.

The Flint Amendment to the UK’s Finance Bill was accepted on 5 September 2016 and empowered ministers to require large multinationals with a headquarters or substantial presence in the UK to publish headline information about their income, employment and taxes. The UK Government has been waiting for a corresponding EU-wide deal on public country by country reporting to progress – but this has been held up and it’s unclear if EU leaders would approve it.

The IMF says that corporate income tax contributes around 16 percent of government revenue in poor countries compared to around 8 percent in rich countries. While corporate income tax rates have fallen in recent years, developing countries are likely to still depend on it roughly twice as much.

How tax collection affects health spending: Financing universal health coverage – effects of alternative tax structures on public health systems: cross-national modelling in 89 low-income and middle-income countries

In July, RB, the British manufacturer of Dettol and Nurofen, called for tougher tax laws that would protect poor countries following an Oxfam investigation.’

October 26, 2017

How Change Happens one year on – the stats, the suffering and the power of Open Access

It’s a year to the day since How Change Happens was published (I made the mistake of putting ‘narcissistic peak’ in

Day 1: Narcissism at first sight?

my diary, and my wife Cathy saw it – never heard the end of it). Here’s what’s happened since.

First the stats: the headline figure is that in the first year, the book has had approximately 40,000 readers. Of these roughly 6,000 bought paper copies, 1,000 bought the ebook, 11,000 downloaded the pdf and 22,000 read it online. I say approximately, because on the downside, people may have downloaded the pdf and not read it, and on the upside, they may have circulated the pdf, which wouldn’t register in the stats. An audiobook is also available, but I have no stats on sales.

I’m happy with the numbers but most interesting from a publishing point of view (and because this is Open Access week) is Oxford University Press’ willingness to go Open Access. That has meant far greater take up, and the ability to disseminate the book’s arguments in places without established book distribution systems. By continent the split for online readers is 39% Europe, 27% North America, 19% Asia, 6% Australasia, 6% Africa, and 3% South America (118 countries in all). Interestingly, OUP reckons that Open Access has not harmed overall sales, and may even have helped (several people have told me they downloaded the pdf, skimmed it, and then ordered the book). It’s also made it possible to discuss the book on numerous webinars and they tell people where they can download it – much more dignified than lamely trying to persuade them to order the book.

Shifting books is a bit like selling your music – if you’re a musician, you need to shift the merchandise at endless gigs, and I’ve spent much of the last year launching the book in the UK, Australia, Denmark, Ireland, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, Sweden, Switzerland and the US, and next week am off for one last heave to the US West Coast and Canada. (Public events in San Francisco on 2 November and lots in Canada the following week). These events have been primarily at Universities, Government Development Departments (Australia, NZ, UK, US, Sweden, Norway), Foundations and NGOs (both international development and, increasingly, other sectors – environment, domestic). I’m particularly excited about the increasing number of conversations with non-aid types, eg social activists in the UK.

The conversations at those launches have been great – top questions include ‘do you believe in the perfectibility of

I’m so glad you rejected these two

mankind?’ and ‘do you lie a lot?’ They have helped me hone the narrative and see where the energy and interest lies for future work (eg on positive deviance). They have broadly confirmed the arguments in the book (at least that’s what I heard!), along with some great critiques from the likes of David Kennedy and Brian Levy.

the energy and interest lies for future work (eg on positive deviance). They have broadly confirmed the arguments in the book (at least that’s what I heard!), along with some great critiques from the likes of David Kennedy and Brian Levy.

Despite the generally positive reception, that level of sustained exposure and scrutiny is pretty bruising in more subtle ways. The endlessly repeated arguments of the book start to sound trite and obvious; the occasional criticism registers 100 times louder than any praise. It wears you down a bit. I’m proud of the book, and deeply indebted to Mark Fried for a great editing job, to the Aussie government for funding the research, and to everyone at Oxfam for their amazing support, but now I really need to move on.

But it won’t be just yet. Translations have been agreed and are under way into Chinese and Spanish, and discussions are taking place on an Arabic translation. Discussions are under way with publishers in a number of other countries – it helps that HCH has a Creative Commons Licence that does not require publishing licensees to be non-commercial or to release their translation as OA (unless they want to), so we can talk to commercial and non-commercial companies alike. The book is the course text for the forthcoming Making Change Happen MOOC co- designed by Oxfam and the Open University, and for a module I am currently writing at the London School of Economics, where I teach.

designed by Oxfam and the Open University, and for a module I am currently writing at the London School of Economics, where I teach.

I’d welcome any feedback from HCH readers – what has/hasn’t been useful, whether/how you’ve applied the book’s arguments etc. Can’t see many of you coming up with stories as good as Wesam Qaid’s. His vehicle broke down while crossing the Yemeni desert, leaving him with nothing to do but….. read How Change Happens. He tweeted ‘I met a 10 year old with a machine gun at a check point in Abyan. Got me thinking lawless doesn’t = power vacuum’ and then tweeted this pic. He arrived safe and sound, by the way.

There are lots of interminable videos of launches on the web, but here’s the shortest, from RSA

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers