Duncan Green's Blog, page 109

October 12, 2017

Can INGOs push back against closing civic space? Only if they change their approach.

Guest post from Dhananjayan Sriskandarajah, Secretary General of

CIVICUS

. He can be found on social  media@civicussg

media@civicussg

Civil society is facing a sustained, multi-faceted, global onslaught. According to the CIVICUS Monitor, fundamental civic freedoms are being severely restricted in an unprecedented number of countries. The operating environment for civil society organisations is becoming more hostile across the world and many of us in the organised bits of civil society – including in the biggest INGOs – are looking for ways to respond. But, those who want to ‘save’ civic space need to tread carefully.

For a start, we need to avoid seeing this issue through the standard North-South development lens. Civic freedoms are being attacked and restricted in countries all over the world, including in mature, Western democracies. And challenges to the legitimacy and role of NGOs are being levelled everywhere, from Honduras to Hungary, from Uganda to the UK. Seeing this as a phenomenon that is limited to fragile, broken states in the Global South, that can be by fixed Western actors misses this increasingly universal reality.

When we do look to the Global South, we see a civil society sector that has already been profoundly affected by the modus operandi of Northern donors and NGOs over the last twenty years. And not always in positive ways. The extensive due diligence and auditing processes of Western donors have sieved the sector, with smaller, less well-connected CSOs slipping through the net and only those larger, better established organisations able to meet high audit thresholds finding support.

Credit: Tony Carr

The exacting requirements of powerful Western donors have forced these organisations to become experts in ‘accounts-ability’, answerable primarily to a funder in London or Washington DC, rather than to the communities they serve. Donors’ insistence that beneficiaries clearly brand the source of their funding has served to further undermine the domestic legitimacy of Southern CSOs, leaving them vulnerable to campaigns of demonisation and accusations of foreign puppetry. The diversity, reputation and resilience of civil society actors, particularly at grassroots level, has been weakened.

Given this context, I find the increasing interest of INGOs in how to push back against closing civic space at once encouraging – because more of us need to engage with this issue – and concerning – because a business as usual approach looks likely to cause more harm than good.

In recent months, we have seen a number of INGOs respond vociferously to threats of expulsion from, or punitive restrictions of their activities within, particular countries. Yet, though we can be fairly sure that for every one threatened INGO, there will be many local organisations already shut down, the response of the INGOs in question has been to focus upon protecting the operating environment for development actors like themselves. Instead of rallying a collective response to a widespread crackdown, civil society has been cast primarily as instrumental to the delivery of development outcomes and the continued presence of an INGO in a particular country as vital to the delivery of a much-needed service or sought after target.

By making the protection of civil society about the protection of development outcomes, we perpetuate the myth that only the international community can save those living in poverty. Pushing back against closing civic space isn’t a technical issue; it isn’t about the apolitical delivery of development targets; it can’t be tackled with metrics and logframes, or time-limited capacity building. It isn’t only about a tightening regulatory and legal context for CSOs. The issue is fundamentally, and unavoidably, a political one. It is about an on-going struggle to negotiate the limits of political power and its interaction with the citizenry; a balance that must be constantly and domestically re-negotiated.

It is by focusing on empowering local civil society that we can help to build the necessary domestic, grassroots

Credit: A. Davey

strength, resilience and expertise that is needed to engage in this continual re-negotiation. This kind of localisation is actually about reinvigorating democracy; it is about empowering and equipping the institutions that engage in democratic life to maintain the balance of power on the side of civic rights. This applies as much to those Western democracies where civic space is under threat, as it does to any country in the Global South.

The political economy of today’s development sector is not geared towards this kind of solution. Power and resources are far too concentrated in the hands of a few largely Western-based big players; their systems designed to facilitate incremental progress towards fixed development targets. If they are to play their part in pushing back against closing civic space, INGOs will need to get out of the aid business and re-engage with the art of social transformation.

October 11, 2017

Achilles v Ulysses and Complexity, according to the OECD

Just been browsing a on what complexity and systems thinking mean for policy-making. It consists

Critical Junctures everywhere

of ‘a compilation of contributions from a series of seminars and workshops on complexity issues over the past two years. It reflects the combined wisdom and perspectives of an internal and external network of researchers, academics and policymakers.’

The pieces are short (couple of pages each) and come from some big and varied names: Andy Haldane, Chief Economist of the Bank of England looks at long-running critiques of economic frameworks; Deborah Gordon, a leading biologist studies ants and systems that operate without central control; Cesar Hidalgo, a statistical physicist from MIT investigates the complexity of the products a country produces and consequent levels of inequality.

Some of the contributions are a bit speech-y and flimsy, but the cumulative impact of reading them is to see an influential community of decision makers/influencers really grappling with how this new thinking can help dig us out of the mess we are in (economic, climatic, political).

There are some good one liners – a Chief Statistician of the OECD urges wonks everywhere “to measure what we treasure and not treasure what we measure” – and the occasional bit of good writing. My favourite was from the OECD’s Patrick Love on ‘what Homer can teach us about complexity’ (that’s Homer from The Odyssey, not The Simpsons). Love contrasts The Iliad (linear, simple, Brad Pitt type hero in Achilles) with The Odyssey (non-linear, complex), concluding:

‘We can learn a final lesson from Homer in the character of his heroes. Achilles is arrogant, immature, impulsive, self-centred (“the best of the Achaeans”, making you wonder what the rest of them were like). He’s strong and is good at killing people but ends up dead. Ulysses is clever and is good at persuading people. He is modest and he listens to advice. He worries about others. And he navigates his way back to Ithaca and Penelope. In a complex world, today or as described by Homer, you will achieve more through strategy and resourcefulness than by brute force.’

But what really exercises him is bad writing (he works for the OECD’s Comms team, so probably suffers a fair bit on that score):

‘Policy experts, like experts in other fields, often defend their poor communication by explaining that the subject is complicated and shouldn’t be dumbed down. Here’s an extract from Einstein’s critique of Newtonian cosmology in Relativity: The Special and General Theory: “If we ponder over the question as to how the universe, considered as a whole, is to be regarded, the first answer that suggests itself to us is surely this: As regards space (and time) the

‘good at killing people but ends up dead’

universe is infinite. There are stars everywhere, so that the density of matter, although very variable in detail, is nevertheless on the average everywhere the same. In other words: However far we might travel through space, we should find everywhere an attenuated swarm of fixed stars of approximately the same kind and density.”

Practically any adult or young person who can read can understand Einstein’s point, however complicated the subject. Here by way of contrast is the OECD explaining a fundamental concept in economics: “…the relative cost differences that define comparative advantage, and are the source of trade, disappear once one reaches equilibrium with free trade. That is, the two countries in the trading equilibrium in Figure 1.2 are both operating at points on their PPFs where the slope is equal to the common world relative price. Thus comparative advantage cannot be observed, in a free trade equilibrium, from relative marginal costs.” Can you tell from this if we’re for or against free trade?’

Lovely stuff, and props to the OECD for letting him take the mick in public.

And as we don’t have nearly enough about ants on this blog, here’s Deborah Gordon’s 15m Ted talk

October 10, 2017

Hugo Slim sets me straight on the state of humanitarianism

I wrote a gloomy piece on the state of humanitarianism recently, and got put straight by some excellent comments from Ed Cairns, Paul Harvey and others. Here’s a particularly erudite rebuttal from humanitarian guru Hugo Slim, who (among other things) is

Head of Policy at the International Committee of the Red Cross. (I’ve added a few links)

:

Here’s a particularly erudite rebuttal from humanitarian guru Hugo Slim, who (among other things) is

Head of Policy at the International Committee of the Red Cross. (I’ve added a few links)

:

Welcome to our world, Duncan.

I’m glad you stuck it out at the recent London conference on protracted conflict. It is very useful to have your development perspective on the challenge of responding to the millions of people who are enduring the suffering and impoverishment of long wars.

A few points to get out of the way early.

First, the inter-governmental “Development Set” can be posh too – meeting in suits and eating canapés. So, I don’t think the “disorienting gulf” between gentility and misery is unique to humanitarian policy circles.

Secondly, development is also dominated by arcane “international machinery”: DAC for one; the many intermediate objectives, indicators and review mechanisms of the SDGs for another. So, in terms of inter-governmental superstructure, we have a lot in common.

Thirdly, a lot of humanitarian work is poverty work – conflict impoverishes people deeply and fast. Today’s “war poor” are usually left furthest behind.

But I want to focus on two very important points you raise: that the humanitarian system is very “top-down”, and that IHL is merely a “dead hand”. You are absolutely right on the first count and wrong on the second, but both are importantly related.

I wish humanitarian action was more a people’s movement than it is. Like you, I believe that activist social movements have done so much to transform the way poverty is framed and responded to by States and international development policy. The principle of “rising up” has always been critical to the anti-poverty movement.

I wish humanitarian action was more a people’s movement than it is. Like you, I believe that activist social movements have done so much to transform the way poverty is framed and responded to by States and international development policy. The principle of “rising up” has always been critical to the anti-poverty movement.

Such upwards movement is always there in people’s response to armed conflict and chronic violence but not perhaps as obviously as in your mass demos. People act courageously on their own initiative, form associations and risk death to help each other. But you are right that their space and their oxygen is often taken from them. Sometimes by the violent force of parties to the conflict, sometimes by expeditionary international agencies.

This is why the current move to “localization” in humanitarian policy is so important to get right. Social movements inspired by humanitarian principles from the ground up are often profoundly creative and resilient. But old problems in development run deep in humanitarian action too: the risks of capture and suppression.

Localization will not be real if it is a power shift captured by elite civil society alone. And many conflicts have the suppression of social movements as one of their core objectives. This means that even when national and grassroots humanitarian action blossoms, it will still need complementary international action by organizations like the ICRC. Sometimes access is only granted to neutral, impartial and independent organizations who have the support of international law and interested States.

Now your point about “the dead hand of IHL”. You suggest that IHL deadens a more imaginative response to civilian suffering because it is out of date and top-down.

IHL is not out of date. Its rules are good. People imagine that it used to work much better in the “good old days” of international armed conflicts between States, and it now cannot keep up with modern times. Such golden age thinking bears no scrutiny. It has always been a real struggle to ensure respect for IHL in inter-state wars as well as non-international armed conflicts. No time was easier than today, and today is no more difficult than times past.

Ensuring people’s protection in armed conflicts is a continuous struggle with significant successes every day  (wounded healed, hungry fed, people safe, families reunited, prisoners visited and water services repaired) and many striking televised failures in which people are forcibly displaced, summarily executed, raped and bombed in their homes.

(wounded healed, hungry fed, people safe, families reunited, prisoners visited and water services repaired) and many striking televised failures in which people are forcibly displaced, summarily executed, raped and bombed in their homes.

So your development movement and my humanitarian IHL movement share the principle of struggle. But you are right to suggest that our struggle looks top-down. This is partly because of the dangers of capture and suppression I have already described. It is partly because there are so many guns and bombs around this struggle as to make it truly existential for many people wanting to organize.

It is also because IHL itself does not lend itself easily to a global movement akin to that around climate change, land rights, labour rights or gender equality. IHL is a set of complicated rules which require interpretation in practice. Successful bottom-up global humanitarian movements have not been in the name if IHL itself but for particular slices of IHL rules: the protection of hospitals; the abolition of land-mines, the prevention of sexual violence, the protection of children and education, and most recently a ban on nuclear weapons.

I hope this may change and that people will make IHL itself a global issue. I would be delighted if a global movement arose with banners demanding that the principles and rules of the Geneva Conventions – recognized universally by States – must be respected. We get close sometimes but still have nothing of the depth and scale of environmental concern, or your own movement to end poverty.

So, I hope your development set may join us. You know a lot of the moves already, and we certainly need support on responding to the deepening poverty created by armed conflicts.

Hugo Slim

October 9, 2017

Want to ensure your research influences policy? Top advice from a Foreign Office insider.

The conference on ‘Protracted Conflict, Aid and Development’ that I wrote about on Friday was funded by the Global  Challenges Research Fund, a massive (£1.5bn) UK research programme that is funding, among other things, the LSE’s new Centre for Public Authority and International Development, where I’ll be putting in a day a week over the next few years.

Challenges Research Fund, a massive (£1.5bn) UK research programme that is funding, among other things, the LSE’s new Centre for Public Authority and International Development, where I’ll be putting in a day a week over the next few years.

Not surprising, therefore, that the topic of ‘research for impact’ kept coming up. A group of us at Oxfam are planning to put a paper together on this (we think we are quite good at it, sometimes), but in the meantime, here are some thoughts based on the conference.

Babu Rahman, a top research analyst at the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), gave some commendably clear advice on what government officials need:

‘What we want from research is not ‘it’s complicated’ or ‘here’s the answer’, but comparative work highlighting a range of possible solutions, showing how particular tools and approaches have worked out. Most useful is understanding where something has/hasn’t worked and why. Then we can apply that to a new situation.

Statistical surveys alone are not that useful – they can generate false confidence or aversion. Multi-disciplinary approaches can be very helpful – even in helping government break down internal siloes. Case studies are really helpful, but limited in generating transferrable lessons – there is a perennial risk of recreate experiences from one place in another, as if they’re templates.

Three quick points on how to make research more useful to officials. All within the broad paradox that civil servants are assessed on their ability to simplify complex issues down to the key components necessary to make a decision, whereas academics’ value lies in illuminating complexity:

Make written work short but not dumb. That requires significant intellectual athleticism.

Avoid jargon and assumed knowledge. We don’t need lots of text on methodology

Structure is really important – go straight to your point in headlines and bullets.

We’re seeing more academics producing abstracts and executive summaries, but they are too often abstracts rather than elevator pitches. Senior officials may have only 30 seconds to get hooked (or not) on what you are trying to say.

We’re seeing more academics producing abstracts and executive summaries, but they are too often abstracts rather than elevator pitches. Senior officials may have only 30 seconds to get hooked (or not) on what you are trying to say.

Attitude: be accessible – what’s often most helpful is when you can sit down with someone and talk to them about your problem. That requires trust and discretion. You have to be able to find the time and navigate the risk of compromise, and your role may not be acknowledged.

The single greatest risk of getting research into policy is that we won’t read it!’

Great stuff. I had a two minute pitch at the end of the conference, by which time most people were comatose, so for them (and anyone else who’s interested), here’s what I added to Babu in messages for academic researchers:

Above all, assume that no-one is going to read your paper. What else can you give them instead? A good exec sum? A blog? A killer fact?

It’s really hard to retain anything from reading a piece of research that has no overall narrative, but it is often equally hard for the researcher to identify a narrative that does not do violence to the research. Nevertheless, we have to try – road testing possible narratives ought to be something researchers spend a lot of time doing, especially towards the end of their research project.

Timing: How can researchers adapt their messages to the rhythm of decision-making set out in the policy

funnel. Think about crises: Officials are most open to new ideas immediately after a crisis/scandal or other ‘critical juncture’, so how can researchers spot these windows of opportunity, drop what they’re doing if necessary, and feed ideas to the suddenly interested bureaucrats and pols? It’s not that easy because crises are also when officials/politicians are busiest and most harassed, so there’s no point in just sticking your old report in the post. The key is to cultivate relationships and trust in peacetime, so that when it all kicks off, you can pick up the phone or drop someone an email offering to help.

funnel. Think about crises: Officials are most open to new ideas immediately after a crisis/scandal or other ‘critical juncture’, so how can researchers spot these windows of opportunity, drop what they’re doing if necessary, and feed ideas to the suddenly interested bureaucrats and pols? It’s not that easy because crises are also when officials/politicians are busiest and most harassed, so there’s no point in just sticking your old report in the post. The key is to cultivate relationships and trust in peacetime, so that when it all kicks off, you can pick up the phone or drop someone an email offering to help.A distressing amount of academic research on aid treats practitioners as fools, or knaves, or both. Try assuming that practitioners are actually smarter than you are, but don’t have the time to do all that thinking and reading, so you are providing a valuable service. That should help avoid some of the plagues of straw men (‘aid does X’, ‘aid people think Y’, any sentence involving ‘neoliberalism’) which are so crude and silly that you immediately give up on the paper (as in this really annoying example)

Which leaves me with two big questions to ponder

Are funders set up to support this kind of research?

To what extent do academic career incentives encourage/prevent these ways of working?

I fear the answer to both is often pretty negative. Thoughts?

October 8, 2017

Links I Liked

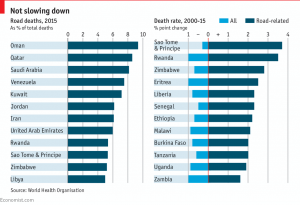

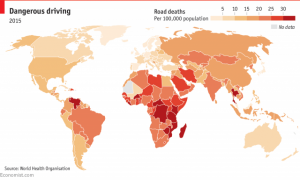

Road deaths in poor countries are one ‘development issue’ that is getting

Road deaths in poor countries are one ‘development issue’ that is getting  worse, not better (click to expand)

worse, not better (click to expand)

‘The defining feature of modern protests is their eclecticism’. Interesting overview of global unrest

Seven challenges for accountability 2.0 by Anu Joshi of the Institute of Development Studies

Lovely tribute from Owen Barder to his father, Brian Barder. The fruit didn’t fall far from the tree (as they say in Latin America).

Lovely tribute from Owen Barder to his father, Brian Barder. The fruit didn’t fall far from the tree (as they say in Latin America).

And another, very sad and untimely death – my lovely LSE colleague Mayling Birney.

Shout out to Wesam Qaid, who broke down while crossing the Yemeni desert, with nothing to read but….. How Change Happens. He sent this amazing pic and tweeted ‘I met a 10 year old with a machine gun at a check point in Abyan. Got me thinking lawless doesn’t = power vacuum’. He arrived safe and sound, btw

Oxfam America has been forced to respond in Puerto Rico due to the lack of government action. Its first US humanitarian response since Katrina

Thorough and even-handed review of the controversial recent study of Liberia’s experiment with private schools by Pauline Rose. ht Max Lawson

History of the world in 20 minutes. Weirdly informative. Highly recommended.

October 5, 2017

Protracted Conflict, Aid and Development: how’s that conversation going?

Spent two days this week discussing ‘Protracted Conflict, Aid and Development’. I was very much a fish out of water

Your discipline or mine?

– the conference was mainly for humanitarian and conflict types, whereas I am a long-term development wallah trying to get my head round these other disciplines as part of my new role at the LSE’s Centre for Public Authority and International Development. And it really hurt (my head, that is). Different language, or different meanings for the same words; people performing an intricate terminological dance – peace, security, amnesty, demobilisation, power sharing, conflict, conflict prevention – to which I don’t know the moves.

But as the conference wore on, the fog cleared a bit, so with advance apology for my flimsy grasp of the subject, here are a few impressions.

Firstly the vibe (academics might prefer ‘discourse’) felt very different from long term development: even more than other aid discussions, there was a disorienting gulf between the chaos and misery being discussed, and the besuited civility of Carlton House Terrace. The discussion is dominated by the international machinery of humanitarian and conflict responses at the UN and elsewhere and so feels tremendously top down. The language is sprinkled with portentous capitalised phrases of various international initiatives – the New Way of Working; the Grand Bargain.

The reality they are dealing with is awful and getting worse. Stephen Pinker’s optimistic take in ‘Better Angels of our Nature’ looks very last decade. Battlefield deaths are sharply up, the number of displaced people currently stands at over 65 million, the highest since World War Two. More non state armed groups were formed in

A long way from Carlton House Terrace

the last six years than in the previous 60. Conflicts are lasting longer, becoming the norm in some countries, rather than the exception.

This has helped trigger ‘a crisis of norms, institutions and tools’ according to Jean Marie Guehenno of the International Crisis Group: ‘Old conflicts don’t die; new ones start; Responsibility to Protect is in very bad shape; international justice is in difficulties. The things we thought were becoming new layers of international governance are now going backwards; dictators are on the up. There are grave doubts on what peace-keeping can achieve. Sanctions are more a sign of impotence than of power.’ His conclusion? ‘The humanitarian system is sometimes like a duck that continues to walk after its head has been cut off’. Ouch.

That crisis has triggered a rethink along the lines of ‘Doing Development Differently’ – more interest in power and politics, systems thinking, in not trying to impose cookie cutter solutions from elsewhere that seldom work. But it feels as if the rethink is being held back by the structure and mental models of the humanitarian sector. Short term and highly unpredictable funding doesn’t help, but the main discussion was a different and less obvious barrier.

Large parts of both humanitarian and conflict thinking base themselves on International Humanitarian Law (IHL), a series of global conventions and commitments, of which the Geneva Conventions on the rules governing warfare are the best known. IHL provides the moral and practical compass, but appears to be becoming less and less useful for two reasons: firstly, IHL is showing its age – it is at its most useful governing conflicts between states, but less useful for non state armed groups and being further undermined by technological advances. One NGO rep asked ‘if a ‘high value target’ is walking across a marketplace (off limits under IHL) and turns on their cellphone, is that now a legitimate target?’

But secondly, IHL is the antithesis of a bottom up, locally embedded approach to change. It is hard to see, at least in

Is that a helping hand or a dead one?

its more formal, legalistic interpretations, how it can be compatible with Doing Development Differently.

Maybe the dead hand of IHL explains why other attempts to rethink humanitarian response, for example by focussing on ‘prevention’ or ‘exclusionary institutions’ thus far seem vague and not very practical, although heading in the right direction.

The aid business seems poorly structured to deal with this crisis. Both official aid agencies and NGOs struggle with the risks of even talking to non-state armed groups; most funding remains siloed and short term, and often driven by donor politics rather than need – a UNDP speaker lamented that aid is politically pro-cyclical – as peacekeeping comes to an end somewhere like Liberia, donors lose interest and development aid falls off too, endangering progress by undermining the peace dividend.

One final question: are those best-placed to try and find a new way of integrating across humanitarian, conflict and long term development the multi-mandate organizations like Oxfam, because getting internal cross-disciplinary cooperation may be easier than between separate organizations? Or does being multi-mandate just tie your hands more comprehensively (eg can’t do advocacy on a country in case it endangers humanitarian access)? Oxfam spends roughly equal amounts on humanitarian and long term development, so maybe we could do more to bring together a group of multi-mandate organizations, raise some research and programme funding, and see what we can come up with/identify areas where people are already getting it right? (At this point, my colleagues will doubtless tell me we are doing it already!)

This is really difficult stuff, and it’s great that the conversation is under way, but it feels both that it has been going on for ages, without much result, and that it has a long way to go, with no definite prospect of success.

Hope commenters on this post can prove me wrong!

October 4, 2017

What should the IMF do differently in Fragile/Conflict States?

Took part in a really interesting discussion about the role of the IMF in fragile states last week. Chatham House rule,  so no names, no institutions. The Fund works in fragile states in 3 main ways – it lends money to governments, it trains officials and it tracks and reports on government economic performance (‘surveillance’). Although its lending is often not big compared to other aid flows, the IMF has disproportionate influence as a gatekeeper, acting as a kind of ratings agency in the eyes of other donors and foreign investors.

so no names, no institutions. The Fund works in fragile states in 3 main ways – it lends money to governments, it trains officials and it tracks and reports on government economic performance (‘surveillance’). Although its lending is often not big compared to other aid flows, the IMF has disproportionate influence as a gatekeeper, acting as a kind of ratings agency in the eyes of other donors and foreign investors.

20 or 30 years ago the Fund was the pantomime villain, a hit man imposing austerity through structural adjustment policies on governments hit by economic crisis. The 1998 photo of Fund boss Michel Camdessus standing, arms crossed, behind Indonesia’s president as he signed a painful bailout agreement came to symbolise its neocolonialist tendencies.

Times have changed, it seems. In Washington it’s as likely to be talking about inequality or gender as balancing the books by cutting spending or even (gasp) raising taxes. In the Greek bailout it was often the voice of moderation against the would-be grim reapers of Germany and the EC. It can be a source of stability, a mentor to governments emerging from chaos and conflict and desperately in need of help to get the machinery of the state working again. It often gets a better press these days.

But how well does its standard repertoire work in fragile states? In theory (and in its staff guidance notes) the Fund recognizes that such places are messier, and require greater attention to understanding the political and social context. But the practice, according to many in the room much more familiar with the Fund than I am, is often pretty close to business as usual.

Can the IMF realign your incentives?

Which got me thinking. The goal of advocates and reformers is often to get a management statement, a new policy or a guidance note that captures their concerns and promises to do things differently. But that often has very little impact on what the institution actually does on the ground – where it is all about culture, rules of thumb and ‘mental models’. My impression is that the Fund’s mental model of a fragile state is of a normal state, only weaker, thus requiring talking to the same people in the same ministries, advocating broadly similar policies and goals, but with more training programmes and maybe more patience about hitting targets.

But fragile states are often not like that – they can be qualitatively distinct from stable ones. Power (what my new LSE research outfit CPAID calls ‘public authority’) is more widely dispersed within society – traditional authorities, Diasporas, faith organizations, ‘non-state actors’ like armed groups may play central roles. In Myanmar I came across armed rebel groups running hydro dams that sold electricity to the government-run cities, and the government paid its bills. In DRC I saw traditional leaders and state officials jointly collecting taxes (and it wasn’t that clear who was in charge).

Fragile states themselves are often unwieldy coalitions of those who want to use the state to improve the lives of citizens, those who want to grab as much as possible, and those who want to do a bit of both.

And the dynamics are chaotic – crises and critical junctures abound. There’s little point in waiting for things to settle down – they won’t. Your 3 year plan will be derailed within months.

Then there’s violence: I’ve been struck in recent weeks by the way the aid business rejects and quarantines the whole subject. It doesn’t usually fit well with the mental model of homo economicus/ rational expectations that underpins so many aid debates; it’s not amenable to 3 year project cycles and technocratic solutions; it ‘belongs’ to a different silo and different specialists (conflict resolution; peacekeeping; counterterrorism), with their own jargon and most of the time the rest of us just wish people weren’t disposed to hurt each other.

subject. It doesn’t usually fit well with the mental model of homo economicus/ rational expectations that underpins so many aid debates; it’s not amenable to 3 year project cycles and technocratic solutions; it ‘belongs’ to a different silo and different specialists (conflict resolution; peacekeeping; counterterrorism), with their own jargon and most of the time the rest of us just wish people weren’t disposed to hurt each other.

Any intervention into such a complex, unstable system is bound to have important consequences, strengthening the hands of some individuals, ministries or arguments and weakening others. Strengthening governments, whether benevolent or malign, relative to other players. Potentially stabilising or destabilising fragile political settlements.

So what should the Fund do? Should it try harder to understand the system in order to do the standards things better (infrastructure, macroeconomic stability, tax collection, encourage investment)? Or should it do different things (invest more in its role as catalyst, bringing together different parties to boost investment, maybe even get into peace-building).

My feeling was closer to the first – the Fund has a valuable role to play in helping governments do the basics, and if it pays more attention to the system, it should be able to play that role better. For that it needs to hire a wider range of expertise – political science and anthropology as well as economists.

One basic point is that it needs to be there – IMF staff are not allowed to even visit the most fragile states, let alone be based there. Safety concerns are entirely warranted – a senior official was killed in a suicide bomb attack on a Kabul restaurant in 2014 – but other agencies continue to function in such places, and you really can’t try and ‘dance with the system’ from a thousand miles away.

October 3, 2017

A draft chapter on blogging and this blog – need your comments please

There’s no way I can come out of this looking good, but I need your help. I’ve been asked to contribute a chapter to a new edition of a Routledge book, Popular Representations of Development: Insights from Novels, Films, Television and Social Media. The topic is…. this blog.

So I have put together what can best be described as 5000 words of evidence-based narcissism and would really appreciate your comments, suggestions for improvements etc. Here’s the draft chapter  .

.

And a couple of excerpts to (hopefully) whet your appetites:

Blogging v other representations of development

Over the years, I have been involved in a range of different roles in aid and development – as an activist, journalist, thinktank writer, scholar, civil servant, NGO researcher and advocate. Each has involved talking and writing about development in different ways to different audiences through different media.

Of all these, blogging stands out as a form of continuous engagement with a specialist audience, in which ideas and arguments can evolve and be sharpened over time. The conversation can be searching and bad ideas can be easily shot down, as I found when I road tested a 2×2 matrix on fragility and conflict in the final stages of writing a book, How Change Happens. The 2×2 never made it into the final text.

Blog conversation is undeniably asymmetric – in this field, the blogger presents themselves as an ‘expert’, or else no-one will click through. It also reflects the broader distribution of power and influence in both society and academia: most international development bloggers are ‘pale, male and stale’ (white, male and old), although national-level blogging is much more diverse. Efforts to diversify the contributors to FP2P have come up against a scarcity of resources and time (for example to work with authors or transcribe interviews). I am currently discussing possible funding with a foundation that could help address this.

Despite such flaws, blogging is often relatively less asymmetric than journalism, film or book-writing, or even academic exchange with students who can be cowed by the power hierarchies within universities.

Public debate is more horizontal, but also more rancorous and often less informed. I am always struck by how little aggression emerges on FP2P, compared to other parts of the internet (I have only ever had one reader you might call a troll, and even he was merely on a nerdy mission to critique Oxfam’s education policy at every opportunity).

Blogging also allows me to build bridges with other representations of development. One of the early posts was entitled ‘I just read four novels in a row’. The informal, personal nature of blogging makes it much easier to introduce other disciplines and forms, recognize the multifaceted nature of readers’ lives and at the same time, have a little fun with the often rather solemn discourse of development in more formal channels. FP2P has used a Bob Marley lyric as an executive summary for an IMF report on food prices and Tolstoy’s War and Peace as an introduction to systems thinking.

The most notorious post: Swimming-Pool Gate:

The Nairobi Swimming Pool post of January 2012 has become somewhat notorious in the aid sector, providing a case study for books such as International Aid and the Making of a Better World. Its popularity lay in laying bare the kind of difficult decisions and dilemmas that are a regular occurrence in aid work, but which are seldom discussed in public.

The Nairobi Swimming Pool post of January 2012 has become somewhat notorious in the aid sector, providing a case study for books such as International Aid and the Making of a Better World. Its popularity lay in laying bare the kind of difficult decisions and dilemmas that are a regular occurrence in aid work, but which are seldom discussed in public.

‘Nairobi is a major NGO hub, currently the epicentre of the drought relief effort, and Oxfam’s regional office realized some years ago that we could save a pile of money if we ran our own guesthouse, rather than park the numerous visitors in over-priced hotels. It’s nothing fancy, definitely wouldn’t get many stars, but it’s much more relaxed than a hotel.

But there’s a problem. As a large converted house in a nice part of town, and like most such houses in Nairobi, it has a swimming pool. But the swimming pool is covered over and closed, even though it would be cheap to keep it open. Why? Reputational risk – back in the UK, where swimming pools are luxury items, Oxfam’s big cheeses saw a tabloid scandal in the making and closed it. It didn’t help when some bright spark decided to advertise for a swimming pool attendant on the Oxfam website……

On my recent stay at the guesthouse, I asked everyone I met there and whether African or expat, they all said it makes sense to open the pool. Exhausted aid workers arrive hot and dusty from remote areas of East Africa for some R&R, but there’s no chance of a refreshing swim. I need my exercise so had to go running instead – the combination of altitude, hills and choking traffic fumes nearly killed me.

On the other hand, there’s no denying that most of our supporters back in the UK, let alone the people we are  working to help, are not likely to have access to a pool in their back yard, so why should aid workers get special treatment?

working to help, are not likely to have access to a pool in their back yard, so why should aid workers get special treatment?

So what do you think? Should Oxfam open the pool and take any bad publicity on the chin, or should we stop whining? It would probably cost about $200-300 a month to keep the pool open – if we could find a way to do it without creating an accounting nightmare, we could probably raise that from contributions from guests, and even have money to spare to plough back into Oxfam programmes.’

The post sparked record numbers of comments (89 to date) and votes. Of 800 people who took part in the poll, 75% urged Oxfam to re-open the pool, while only 7% argued for keeping it shut.

However the post itself became part of the problem, when it was picked up by anti-aid journalist Ian Birrell in an article in The Spectator, which argued that ‘Mr Green’s blog highlighted the contortions of a thriving industry that would go out of business if it succeeded in its stated aims.’ In the middle of a famine response in East Africa, Oxfam press officers were forced to handle enquiries from journalists about the Great Swimming Pool Debate. I had to apologise to them, and as far as I know, the pool remains closed.

If you have time to skim the chapter, please stick your comments on the blog, or if they’re too rude for public consumption, email me at dgreen[at]oxfam.org.uk

October 2, 2017

Local thinktanks are natural allies in ‘Doing Development Differently’ so why not support them better?

Just been reading a rather good paper by Guy Lodge and Will Paxton making the case for supporting thinktanks in  developing countries. They’ve been doing just that for several years, building on their experience in the UK at IPPR and No. 10 Downing Street respectively, hence the paper. They both now work at Kivu International.

developing countries. They’ve been doing just that for several years, building on their experience in the UK at IPPR and No. 10 Downing Street respectively, hence the paper. They both now work at Kivu International.

The starting point is that thinktanks are natural allies in the effort to ‘Do Development Differently’: ‘Think tanks are often better placed to influence policy than traditional civil society organisations (CSOs), while their research tends to be more politically informed than academic research. Yet CSOs and academic institutions tend to be more prominent on donor radars.’

Navigating the unpredictable rapids of complexity means you want lots of agile rafts, as well as (or instead of) supertankers like DFID (or Oxfam) or less attuned northern thinktanks. Good local thinktanks could be a better fit, not least because:

‘Unlike outsiders they don’t need elaborate theories of change or Political Economy Analysis (PEAs) to understand how the internal power dynamics operate in their country. They have the local knowledge to understand how decisions are made, what formal and informal processes matter and how the patronage networks which may exist  will help or hinder the prospects of achieving change. This kind of politically savvy thinking is – or is potentially – second nature to them. Indeed, often think tanks will have people who have worked in government and who understand the realities of policy making and politics.’

will help or hinder the prospects of achieving change. This kind of politically savvy thinking is – or is potentially – second nature to them. Indeed, often think tanks will have people who have worked in government and who understand the realities of policy making and politics.’

The authors identify five distinct ways in which think tanks seek to exert influence:

‘1. Direct policy influence: where a think tank advocates for the implementation of a specific proposal which is subsequently adopted by government.

Indirect policy influence: where a think tank proposal shifts policy, but only as part of a messy and complicated process where a range of different interests all shape a change in policy direction.

Influence the broader climate of ideas: this is often where they can have most impact, where they reframe a policy debate around new ideas.

Informing public debate on key issues: through their communication and dissemination work they can play an important role informing public debate.

Hold governments accountable: for example, by monitoring policy implementation or providing evidence to show policies are not achieving results.’

Local thinktanks use their local savvy to match these different ways of working to their political environments: if you are in Rwanda, you follow an insider track; if you’re in more democratic, noisy Zambia, you do more in public.

The paper is basically a pitch to donors, who, the authors argue, are putting too little money in, and in the wrong ways. Since thinktanks need a functioning government to engage with, the most promising countries are low/middle income but stable (i.e. not fragile/conflict states). They need money (relying on domestic funding too often comes with big political strings attached), but also a change in attitude.

‘Think tanks [often] have – or aspire to have – strong academic cultures. Here a familiar problem is placing a  premium on academic rigour (often encouraged by donor funding) over carrying out policy-oriented and politically savvy research. This often leads them to use inappropriate methods which don’t fit with skill-sets and the timelines needed to influence policymakers. Indeed, a desire to demonstrate academic credibility can mean that think tanks inadvertently neglect to use their local knowledge and political insights, in favour of carrying out academic research.’

premium on academic rigour (often encouraged by donor funding) over carrying out policy-oriented and politically savvy research. This often leads them to use inappropriate methods which don’t fit with skill-sets and the timelines needed to influence policymakers. Indeed, a desire to demonstrate academic credibility can mean that think tanks inadvertently neglect to use their local knowledge and political insights, in favour of carrying out academic research.’

That rings true – there’s maybe a bit of isomorphic mimicry going on here, with thinktanks jumping through lots of methodological hoops (think RCTs) that don’t play to their strengths.

The authors argue for ‘seeding’ the policy ecosystem by core funding lots of new thinktanks, including the more experimental/innovative variety (higher risk, from a donor point of view, but potentially more influential). They identify three emerging roles for such experimentation:

‘• Political insights: explicitly developing the expertise and knowledge of local political context, for example through carrying out ‘political and power’ assessments on any given issue, and for instance developing an expertise in polling.

Elite convening: developing a function which not only facilitates debate and discussion between key interest groups but which looks to identify collective interests and coordinate actions across these different stakeholders to help bring about policy change. This would also entail think tanks building partnerships with specific and potentially powerful interests, such as the church, which carry more weight than themselves.

Campaigns and alliances: essentially this would mean engaging in more bottom-up approaches to policy influence, whereby think tanks leveraged the power of citizens and communities to press the case for reform.’

All seems very sensible – I’d be interested in hearing from donors/thinktanks about whether this makes sense/what’s missing, and from those (looking at you IDRC) who’ve already been doing this for years.

October 1, 2017

Links I Liked

This is Albert Einstein’s other great equation: a formula for the survival of the living world and its people. Four  sentences, written in 1950. ht George Monbiot

sentences, written in 1950. ht George Monbiot

Q: How does a government regulate new stuff that it doesn’t understand? A: completely rethink of regulation as a process of iterative partnership with the regulated.

New twist on sexism in academia. Women academics are systematically (and unfairly) marked down by students (both sexes) in their evaluations. Sigh.

The worst refugee crisis in decades: the weekly outflow of Rohingyas from Myanmar is the highest since the Rwandan genocide

The worst refugee crisis in decades: the weekly outflow of Rohingyas from Myanmar is the highest since the Rwandan genocide

The power of culture continued: Students (especially girls) who watched the Queen of Katwe movie were more likely to pass exams than those who did not,

Check out the new Global Poverty and Inequality Dynamics (GPID) research network website

Interesting typology of ‘scholar practitioners’ – I think I’m a ‘temporary role bundler’….

Brexit meets Titanic. A wonderful (if depressing as hell) spoof. via Henry Northover

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers