Duncan Green's Blog, page 112

August 31, 2017

What can we learn from 7 successes in making markets work for poor people?

Hi everyone, I’m back from an August blog break, with lots of great reading to report back on. First up, if you’re even slightly  interested in how markets can benefit poor people, I urge you to read Shaping Inclusive Markets, a new publication from FSG and Rockefeller. The 60 page document explains their approach to ‘market systems innovation’, which we discussed at an event in February (blog here, so I won’t repeat it).

interested in how markets can benefit poor people, I urge you to read Shaping Inclusive Markets, a new publication from FSG and Rockefeller. The 60 page document explains their approach to ‘market systems innovation’, which we discussed at an event in February (blog here, so I won’t repeat it).

The new paper pulls together the lessons from 7 case studies of long term success, along with FSG’s top tips to aid donors, governments etc on how to promote inclusive markets. It covers lots of the How Change Happens topics (systems, critical junctures and tipping points, alliances, the importance of norms), but all in terms of how they affect the evolution of markets.

One case study stands out among the seven – the transformation of dairy farming in Gujarat from 1940 to the present, from an exploitative system where farmers were exploited by middlemen, to a vast network of farmer-owned organizations, who now receive 70% of the market price of an ever-expanding range of dairy products. (Other case studies cover Colombian coffee; Kenyan tea; Tourism in Costa Rica; Water provision in Manila and retail financial services in Kenya and the US, all of them taking place over decades rather than years).

Reasons for loving the report:

The use of timelines: The research invested seriously in building up a timeline of each case study, looking at the interaction between events, market rules and business models and practices. In my own work on case studies of change, I’ve found that investing early on in timelines has a huge pay off – helps pull out divergent stories of change, and the interaction between different elements (eg Indian independence, the role of particular business leaders, new technologies, grassroots mobilization). See the Gujarat dairy timeline for a sense of the scale, duration and systemic nature of the change.

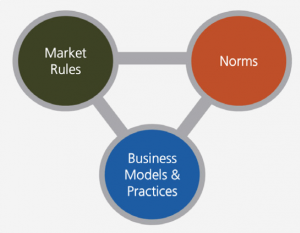

Thinking in s ystems: ‘One of the popular narratives in the philanthropic and aid sector today is about how we could take a single innovation and scale it up by overcoming obstacles in the wider system around it. Indeed, even experts at FSG and The Rockefeller Foundation have tended to operate with this perspective and written in the past about how this could be approached. However, when we look across the broad sweep of our case studies, what we see is less about the scaling up of any one innovation and more about how a panoply of innovations comes together over time, interacting with and building on each other, in order to progress the market. Importantly, these innovations reshaped not just business models and practices, but also the formal laws, regulations, and policies that apply in the market and the informal norms that guide the behaviors of various actors. Put more simply, we see innovation in relation to both the players and the rules of the game.’

ystems: ‘One of the popular narratives in the philanthropic and aid sector today is about how we could take a single innovation and scale it up by overcoming obstacles in the wider system around it. Indeed, even experts at FSG and The Rockefeller Foundation have tended to operate with this perspective and written in the past about how this could be approached. However, when we look across the broad sweep of our case studies, what we see is less about the scaling up of any one innovation and more about how a panoply of innovations comes together over time, interacting with and building on each other, in order to progress the market. Importantly, these innovations reshaped not just business models and practices, but also the formal laws, regulations, and policies that apply in the market and the informal norms that guide the behaviors of various actors. Put more simply, we see innovation in relation to both the players and the rules of the game.’

Learning from Success: ‘What if we saw the wider market system not only as a place of failure, challenges, and barriers that we needed to somehow fix, but also as the source of innovation and change that could be supported and harnessed? Many of us working with market-based solutions and impact enterprise were used to seeing this innovative potential in the business sector, but were less accustomed to looking for it and appreciating it in other sectors, such as civil society and the public sector. And yet, just as is in the business sector, the pockets of innovation in the wider system represent the glimmers of hope, the seeds of opportunity that hold the potential for transformation. We believe that harnessing all of these areas of innovation is the key to helping to advance more inclusive economies.’

Critical Junctures: ‘A key theme that emerged from our case studies is how key innovators were able to exploit powerful external events, such as economic or political crises, to push through change. However, the capacity of those innovators to do so was always built up before the events occurred. The implication of this is that we should support the capacity building of innovators to prepare them to take advantage of significant events and be ready to step up or otherwise adapt our support when those events actually occur.’

such as economic or political crises, to push through change. However, the capacity of those innovators to do so was always built up before the events occurred. The implication of this is that we should support the capacity building of innovators to prepare them to take advantage of significant events and be ready to step up or otherwise adapt our support when those events actually occur.’

Saying ‘hey everything is complex’ can induce high levels of doubt and anxiety, with people endlessly commissioning further studies and putting off taking action. FSG does its best to avoid such ‘analysis paralysis’ by setting out a market systems approach that focusses on the interaction between market rules, business models and practices and social norms. Intervening in each of these requires a combination of

Analysis of existing documentation and data

Sensing and observing changes and patterns by engaging with and listening closely to a large network of actors embedded within the system, so that you pick up real time changes and opportunities

Probing the system by experimenting with initial interactions – a ‘portfolio of bets’ (a pilot, a piece of draft legislation to assess feasibility), on the basis of which larger scale interventions can be designed.

All great stuff – I’d be interested in your feedback on the paper

August 9, 2017

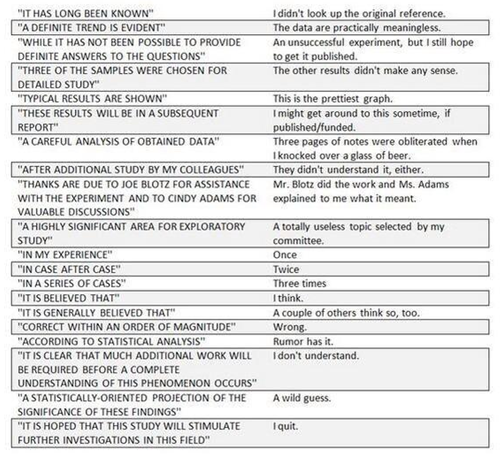

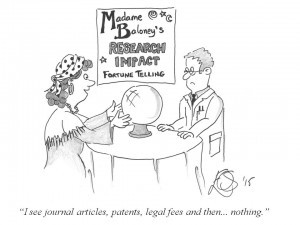

What researchers say v what they mean

This handy translation device from Claire Hutchings is reminiscent of an FP2P all time favourite ‘what Brits say v what they mean’. On the left, what they say; on the right, what they mean. Enjoy (and send me other similar exercises).

And with that, I’m heading off on holiday – two weeks in the Scottish rain, including a week replenishing my parched hinterland at the Edinburgh Festival. And when I come back, the blog is staying dark for a bit, until I catch up with my reading. See you in September.

And with that, I’m heading off on holiday – two weeks in the Scottish rain, including a week replenishing my parched hinterland at the Edinburgh Festival. And when I come back, the blog is staying dark for a bit, until I catch up with my reading. See you in September.

And here’s the definitive walking-in-Scotland clip

August 8, 2017

How might a systems approach change the way aid supports the knowledge sector in Indonesia?

For some reason, the summer months seem to involve a lot of cups of tea (and the occasional beer) with interesting people passing  through London, often at my second office in Brixton. One of last week’s conversations was with Arnaldo Pellini, who has been working for ODI on a big ‘knowledge sector initiative’ in Indonesia. Five years in, the team is thinking less in terms of a knowledge sector, more as a knowledge system, so we discussed what systems thinking might add to the work.

through London, often at my second office in Brixton. One of last week’s conversations was with Arnaldo Pellini, who has been working for ODI on a big ‘knowledge sector initiative’ in Indonesia. Five years in, the team is thinking less in terms of a knowledge sector, more as a knowledge system, so we discussed what systems thinking might add to the work.

We started with the evolutionary cycle: systems evolve through the endless churn of variation, selection and amplification. Variation = rate of mutations – new species, new companies; Selection = some are fit for the landscape, others are rubbish and die out; amplification = the fit ones expand or proliferate and become Facebook, Google, or ants. At some point, they may become so dominant that they start to stifle new cycles of variation, at which point governments (or ant-eaters) need to get stuck in to reduce their power.

Is there more to life than flipcharts?

So how might this apply to a programme team managing the funding / receiving funding (the KSI is funded by the Aussies) to look for wasy to strengthen a knowledge system?

Variation

A programme team could look to deliberately accelerate the rate of mutation: it could fund research to speed up the emergence of ideas and technologies, or support start ups to put those ideas into practice, (eg by helping them find start-up capital) or encouraging entrepreneurs/venture capitalists to come and do it instead.

Selection

Say KSI helps seed the system with 30 new start-ups or support innovative ideas in established organisations in the knowledge system. How could it make sure that the fit ones prosper and the unfit ones die? (programmes tend to struggle with deciding when to stop funding something that does not show traction). If the start-ups are operating commercially, there is a bottom line that can do that for you – one of the great strengths of markets is the ‘creative destruction’ that constantly selects new winners, and kills off losers. If they are not operating in a market logic, you need to find an alternative mechanism for feedback and selection, preferably not a bunch of aid wallahs behaving like Roman emperors giving thumbs up/down to the gladiators. Customer feedback? Evidence of demand?

Amplification

A few good ideas have popped up, and survived. How can they go to scale or expand in a huge country like Indonesia, and as fast as

Or panels (even women-only ones)?

possible? Is it access to finance? Or maybe turn them into a social franchise (‘project in a box’) that can be rapidly replicated and adapted by anyone interested in picking it up?

No donor or other would-be philanthropist can tackle all of these, nor should they. There is an autonomous system of knowledge already there, churning out ideas, successes, failures and change. Perhaps the best thing to do is first understand that system, then try and identify where the web of variation, selection and amplification is weakest, or is breaking down, and try and focus your attention there. Maybe they could draw on Dani Rodrik and Ricardo Hausmann’s work on growth bottlenecks.

One implication of this approach is for the way programmes design their budgets and spend money. Twelve months or even 5 year budget cycles struggle with a system approach. Here is an idea. What if programmes could transfer the underspent budget from one year to the following year to support the initiatives that show traction? Or, what if programmes could start with a small budget to support experimentation at the early stages and increase the size of the annual budget over time? There is probably a need here to rethink how budget and planning processes fit with the stages of evolution of a system approach. For example, variation might be a lot more about facilitating the exchange of ideas and connections, which needs people more than cash.

Thoughts?

August 7, 2017

Capacity development is hard to do – but it’s possible to do it well

Lisa Denney’s gloomy take on the state of capacity building in the aid industry prompted quite a few comments and offers of blog  posts, including this from Jon Harle of INASP, on organization that ‘

strengthens the capacity of individuals and institutions to produce, share and use research and knowledge, in support of national development.’

posts, including this from Jon Harle of INASP, on organization that ‘

strengthens the capacity of individuals and institutions to produce, share and use research and knowledge, in support of national development.’

Lisa Denney’s recent blog – and Arjan de Haan and Olivia Tran’s response – raise some important issues about what capacity development really is, and whether it works. I agree with the central thrust of Lisa’s argument: that often, capacity development amounts to little more than a few training sessions, with no real attempt at sustainable or transformative change.

But, at INASP, we think capacity development is an important investment, and it is possible to do well. We were surprised to hear capacity development referred to as the ‘quick win’ in a project at a recent seminar, because, our belief is that real capacity development only happens where work is demand-driven, is Southern-led, and is based on long term engagement and partnership.

INASP shares similar interests to ODI and IDRC – our purpose is to strengthen research and knowledge systems in the South. We certainly wouldn’t pretend that we’ve always got it right– we’ve made plenty of mistakes of our own over the years — but in the process we’ve learnt a lot about how to improve the long term impact of our work.

INASP shares similar interests to ODI and IDRC – our purpose is to strengthen research and knowledge systems in the South. We certainly wouldn’t pretend that we’ve always got it right– we’ve made plenty of mistakes of our own over the years — but in the process we’ve learnt a lot about how to improve the long term impact of our work.

Beyond training – putting capacity into practice

While training is important, it’s vital to look beyond training to find other ways in which individuals and groups can be enabled to learn and solve problems.

One of the reasons we think that training often falls down is that it focuses on acquiring knowledge or skills, but not on putting them into practice. Our work is as much about convening, collective problem solving and influencing, as about training and mentoring.

For example, we’ve facilitated a series of forums on strategy, influencing and leadership, which are helping partners to turn ambitious visions into practical plans. This makes use of a range of exercises – from succession planning, to help with fundraising or exploring issues of institutional power and inequality – and draws on a network of advisors from business, civil society and academia.

Enduring capacity

Often, interventions focus on building skills within a specific group of individuals, and the skills of this group represent the enduring capacity element of a project. But the ability of the organisation – or wider system – to reproduce those individual skills (without relying on an external partner or funding) hasn’t fundamentally changed.

A major focus of INASP’s work has been to address this by challenge by embedding training abilities within an organisation. For example, many initiatives have sought to train researchers in how to communicate their work (including our own AuthorAID programme). But each year there is a new cohort of researchers looking for support. We therefore also work with research institutes and universities so they can develop and run their own in-house training and mentoring programmes.

As well as training trainers, this also requires changing organizational processes and systems if that skills-development is going to  continue.

continue.

But acquiring skills is just the start. An organisation needs the structures, processes, and ways of working to make use of skills, and individual incentives need to be addressed, if day to day practices are to change.

Having developed an evidence-informed policymaking toolkit to train civil servants in policy roles, we worked with ZeipNET in Zimbabwe to help the Ministry of Youth, Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment build its new Research and Policy Coordination Unit. The toolkit formed the foundation for individual skills training, a series of policy dialogues enabled broader conversations about evidence within specific policy debates, and direct support to the unit’s deputy director to identify and address some of the changes to ways of working at the organisational level.

Our approach

At INASP, we work with local organisations not just as the ‘recipients’ of capacity development, but as the organisations designing and running programmes with us. This helps us to develop a better understanding of the local social and political context that will enable, or constrain change. For example, the ways in which gender and power intersect: do women get the same opportunities? can they  participate in learning spaces? What will enable or block their ability to drive change with new skills or knowledge? We also recognise the constraints that busy professionals face, so we use online training, for example, to provide the flexibility of time and location that face to face sessions don’t allow.

participate in learning spaces? What will enable or block their ability to drive change with new skills or knowledge? We also recognise the constraints that busy professionals face, so we use online training, for example, to provide the flexibility of time and location that face to face sessions don’t allow.

We use a ‘levels of change’ framework which identifies the individual, organisational and environmental levels of a challenge, and the connections between them. By understanding how and which capacities need to be strengthened at these different levels, and be being clear about learning goals, we can start to develop work which is more effective and more systemic in nature.

At the individual level, we may start with the need to creating initial awareness about the importance of new skills or knowledge, then build the basic ‘starting knowledge’ or skills needed, subsequently strengthening skills or deepening knowledge, and finally putting this into practice in the workplace.

At the organisational level, the need might be to strengthen relationships or exchange knowledge between teams, improve structures and processes, enhance management approaches, or even change organizational culture.

At the environmental level we may need to strengthen relationships or knowledge exchange between organisations, either at national international level.

As Lisa argues, when capacity development is seen as a technical project, delivered through a limited toolkit which puts too much emphasis on training, and not enough attention to individual incentives or organisational cultures, the messy, politicised nature of social change is ignored.

But, being clearer about how we expect capacity to lead to change, the problems we’re trying to address, the specific learning needs, and the connections across systems, mean that it can be an important and powerful investment in social change.

August 6, 2017

Links I Liked

Geeks Franziska Mager and David Evans contributed their favourite cartoons about control groups (really)

Geeks Franziska Mager and David Evans contributed their favourite cartoons about control groups (really)

‘Information does not lead to political accountability’. Important null result from some serious research raises big questions for transparency activists

Best of luck to USAID’s new boss, Mark Green (no relation). Here’s a handy briefing for him on why the aid budget matters and a nice example of what his agency is doing right (on aid transparency).

Feminist foreign/aid policy is catching on (Sweden, Canada), but what does/should it mean? Oxfam’s Gawain Kripke goes back to 1st principles

Bus seats mistaken for burqas by members of anti-immigrant group. You really couldn’t make it up

The power of the long march. Interesting reflection on Turkey and beyond

Stick your income in here and find where you are in the global pecking order. You’ll probably feel a lot richer afterwards….. ht Ana Arendar

The pro-Brexit Daily Express seems a little confused about border controls – perhaps they didn’t realize that they apply in both directions……

August 3, 2017

Looks like the NGOs are stepping up on ‘Doing Development Differently’. Good.

For several years I’ve been filling the ‘token NGO’ slot at a series of meetings about ‘doing development differently’ (DDD) and/or  ‘thinking and working politically’ – networks largely dominated by official aid donors, academics, thinktanks and management consultants (good overview of all the different initiatives here). Periodically, a range of NGOs appear on the scene, and according to ODI and Care are doing plenty on the ground, but they haven’t been very organized about it. So I was delighted when earlier this week, World Vision pulled together a bunch of international NGOs who are already working on and circulating draft papers about DDD to discuss (Chatham House Rule) setting up a network.

‘thinking and working politically’ – networks largely dominated by official aid donors, academics, thinktanks and management consultants (good overview of all the different initiatives here). Periodically, a range of NGOs appear on the scene, and according to ODI and Care are doing plenty on the ground, but they haven’t been very organized about it. So I was delighted when earlier this week, World Vision pulled together a bunch of international NGOs who are already working on and circulating draft papers about DDD to discuss (Chatham House Rule) setting up a network.

Why does it matter for INGOs? Because the DDD discussion could inform our work in a lot of areas where we are trying to get our act together: power and context analysis, theories of change, adaptive management, localization, making ‘partnership’ more genuine.

What can INGOs bring to the party for the wider DDD community?

Complementary strengths: on a good day, NGOs are closer to the ground, or at least to partners who themselves are working directly with communities (DDD looks very different depending on whether you are directly operational, or work through local partners). That could help address a nagging concern about DDD – the incongruity of a movement dedicated to ‘politically smart, locally led’ development being led by a bunch of senior, mainly white aid wallahs in London, Washington etc. For example, we can introduce more emphasis on participatory processes and ‘bottom-up thinking’ into what are often very top down approaches to ‘political economy analysis’.

We understand power differently: INGOs stress the importance of ‘informal power’ – what goes on in people’s heads (‘power within’), the importance of organizing to achieve ‘power with’. That’s why we go on about gender so much. The existing DDD crew have a lot to teach us on more formal channels of power – political settlements, elite bargains etc etc. Lots of opportunities for a useful exchange there (especially on the interface between informal and formal).

Can NGOs move the needle to the left?

Triggering a necessary argument: DDD has been in fuzzword territory so far – a useful degree of blurring and ambiguity over what it actually means has allowed lots of people to buy into it, even if on some level, they disagree about what DDD means. For example, is DDD about effectiveness (aid donors getting better at persuading governments to do what you think is good for their country) or empowerment (including helping local people change the government, if that’s what’s required)? At some point the benefits of fuzziness may fall relative to the costs of confusion, and the NGOs could help get that clarifying conversation going.

A focus on how money changes hands: It was clear from the conversation that the way aid is funded is critical to encouraging/discouraging DDD. Yet that topic hasn’t got much attention so far in the DDD fora. INGOs find it much easier to do DDD with unrestricted than with restricted funds tied to particular projects and indicators. The current boom in Payment by Results in theory could encourage DDD, but in practice seems to promote Business as Usual conservatism. Project timescales are crucial – much easier to try things out, learn, adapt etc in a 5 year programme than a 12 month one. Lots to learn there.

So what are the next steps for our incipient NGO caucus?

Harvest existing practice: as our recent draft paper found, there is lots of DDD-type practice already going on, so we need to pull that together across a range of INGOs and see what patterns/lessons emerge.

Identifying examples of good donorship: most of the time, INGO people whinge about the way funders cramp their DDD style,  but I have definitely seen examples in Oxfam where the reverse is true – innovative funding approaches by donors have forced us to try out new stuff. We need to collect and analyse such examples, and then lobby like hell for more of them.

but I have definitely seen examples in Oxfam where the reverse is true – innovative funding approaches by donors have forced us to try out new stuff. We need to collect and analyse such examples, and then lobby like hell for more of them.

Exchange between NGOs: like any large institutions, NGOs have their share of blockers (ideas, interests, institutions) as well as advocates for DDD. Lots of opportunity for peer to peer support on this to build up the knowledge, confidence and profile of the good guys.

As for how we promote DDD within the NGOs, I could see three options:

Positive Deviance: identify the examples of good practice that are already there, and make a big fuss about them

Weaken the disabling environment: identify what is stopping DDD spread (whether internal or external) and try and neutralize it (a bit like DFID did with its Smart Rules)

Strengthen the enabling environment: What would need to change to make DDD the norm in NGOs? HR (who we recruit, how we train staff)? Processes (reporting, procurement etc)? Incentives?

So as usual, the NGOs are a bit late to the party, but we’re there now, headed for the kitchen and the bottles of warm Chardonnay, and preparing to get down and dirty. Get ready for some embarrassing dance floor performances ……

August 2, 2017

NBA Superteams and Inclusive Growth: Doing Private Sector Development Differently

Guest post from Kartik Akileswaran of the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change (which is what the Africa Governance Initiative  now calls itself)

now calls itself)

For as long as I can remember, National Basketball Association (NBA) fans, analysts, and team owners have worried that the dominance of a few teams would hold back the league. Many have advocated for rule changes to counteract this trend—but is “leveling the playing field” really the best way to boost the NBA’s popularity?

This year, the same “superteams” had a shot at the Finals and the Warriors won again, yet measures of the NBA’s success are as strong as ever. Viewership records are being broken, team valuations are soaring, and the game is gaining in popularity worldwide. The lack of a level playing field may not be detrimental to the health of the NBA; rather, it may be the cause of it.

Picking winners?

I see parallels between this situation and the debate in the development community between those who favor enabling environment reform (to “level the playing field”) and those who argue for industrial policy (to focus on potentially “dominant” sectors) to promote economic growth. My colleagues and I at the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change argue in our recent paper that capitalizing on high potential sectors—through modern industrial policy—is an essential complement to and guide for enabling environment efforts. Although many governments and development experts are coming (back) around to the idea that modern industrial policy is necessary, they are struggling with how to put it into practice.

Part of the answer lies in something Duncan has written about previously: applying the Doing Development Differently (DDD)/Thinking and Working Politically (TWP)/Problem-Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA) thinking beyond governance, to inform discussions around the “how” in other sectors. We have employed ideas from the DDD/TWP/PDIA movements to help governments avoid the pitfalls of past industrial policy efforts. Here are three things we’re learning about doing private sector development (PSD) differently.

First, PSD efforts should be driven by a focus on the right problems—that is, on the key constraints that, if relaxed, will have real benefits for the country and that local actors prioritize.

This seems obvious, but we have seen many PSD initiatives that target less promising sectors or less critical constraints. This stems from development partners’ tendency to work to their own agendas, instead of following the lead of government and firms. Granted, these local actors may need support in identifying the roots of these constraints. What’s important, though, is that the problems they want to solve remain front and center.

Our experience in Liberia underscores the point. There, we saw that government and development partners had been carrying out generic enabling environment initiatives, such as untargeted infrastructure development and property rights reform. In the meantime, the binding constraints in the sectors with “superteam” potential—such as rubber processing, oil palm processing, cocoa, and fisheries—went largely unaddressed for ten years. Due to the lack of focus at the center of government, various ministries had developed distinct plans for these sectors that were misaligned and poorly resourced. As a result, the challenges of private sector actors were not being addressed in a structured way. To relieve this gridlock, our team in Liberia worked with different government agencies to forge a consensus vision and eventually a harmonized plan focused on six agriculture value chains.

The results have been encouraging: Liberia has exported processed rubber products for the first time since the country’s conflict, and investment in oil palm processing and cocoa have increased. Critical to our support in this process is that we’ve cultivated genuine ownership among all government actors, by supporting them to home in on the most pressing problem(s) and to coalesce around them to make real progress.

Second, the common refrain “it’s the politics, stupid!” needs to be brought to life.

We’re hardly the first to make this point—encouragingly, most development organizations today agree. The challenge is applying this thinking to what they do on Monday morning, so to speak. In our aforementioned paper The Jobs Gap, we lay out some principles and examples on how to work in a politically smart way.

For instance, in Sierra Leone, rice is one of the most important agricultural commodities, but local producers struggle to compete with imported rice. Recognizing this predicament, key officials in the Ministry of Trade and Industry and the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Food Security sought to tip the balance toward local production. These officials not only had to address the technical challenge of competition with imports; they also had to face up to the political challenge that the rice importers’ cartel posed, which runs a lucrative business based on preferential foreign exchange rates and connections across all levels of government.

Given this situation, our staff first supported these officials to set a goal of sourcing locally 10% of the rice demanded by public  institutions (mainly the police, military, and prisons). This framing was vital because it made the problem more manageable and ensured that the initiative wouldn’t infringe too much on the territory of the strong importer lobby. We then worked with a range of stakeholders to plan, execute, and monitor this trial effort (implemented by the private sector), and facilitated problem solving as obstacles related to financing, procurement, and supply revealed themselves over time. Well on the way to the 10% goal, this effort illustrates the importance of building local constituencies for reform, and that starting with “small bets” is a politically savvy (i.e. non-threatening) way to do so.

institutions (mainly the police, military, and prisons). This framing was vital because it made the problem more manageable and ensured that the initiative wouldn’t infringe too much on the territory of the strong importer lobby. We then worked with a range of stakeholders to plan, execute, and monitor this trial effort (implemented by the private sector), and facilitated problem solving as obstacles related to financing, procurement, and supply revealed themselves over time. Well on the way to the 10% goal, this effort illustrates the importance of building local constituencies for reform, and that starting with “small bets” is a politically savvy (i.e. non-threatening) way to do so.

Third, it is extremely useful, if not essential, to create a team inside of government that can drive action, be a focal point for coordination across government and with the private sector, and foster learning and adaptation.

Intra-government and public-private coordination are widely thought to be key for successful industrial policy, and since there’s no foolproof way to determine in advance which sectors and policies will do best, this process must include built-in mechanisms that enable governments to make course corrections over time. No matter the policies being adopted, how they are put into practice matters immensely.

In Ethiopia, for example, the government wanted to develop a new strategy for its pharmaceutical manufacturing sector. The success of this strategy exercise hinged on the establishment of a “nerve center”, staffed by the Ethiopian Investment Commission and the Institute. This team took an iterative approach, convening key stakeholders from government and the private sector on an ongoing basis to identify sector challenges. The team captured learnings from these interactions and used them to frame and refine the strategy. The outcome? A strategy that’s based on thorough analysis, fits the government’s needs, and is action-oriented. The next challenge for this team, of course, will be to help push forward implementation.

Our experience suggests that only when DDD tenets and approaches move beyond the governance space will their full value come to light. We have certainly found them useful in our work on PSD. We don’t have all of the answers, so we hope to hear about how others are supporting governments to discover their “dominant” sectors and thus spur growth. Following in the NBA’s footsteps wouldn’t be such a bad thing.

Our experience suggests that only when DDD tenets and approaches move beyond the governance space will their full value come to light. We have certainly found them useful in our work on PSD. We don’t have all of the answers, so we hope to hear about how others are supporting governments to discover their “dominant” sectors and thus spur growth. Following in the NBA’s footsteps wouldn’t be such a bad thing.

Kartik Akileswaran supports the Government of Ethiopia to develop and implement sector strategies as part of its overarching economic growth plan. He is an Advisor with the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change.

August 1, 2017

Of Course Research Has Impact. Here’s how.

Irene Guijt

, Oxfam GB’s head of research, puts me straight after my

recent scepticism

about the impact of research.

And I don’t mean personal impact on CVs. At the annual Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) impact award ceremony in Westminster, I got a glimpse of the best of what that Research Council has to offer society. I was deeply impressed (even if prize winners are inevitably unrepresentative).

As Oxfam’s head of research, I’m obviously biased, but I think INGO research can have real impact. Take the three years of research on Davos that Shami Chakrabarti, the shadow Attorney General, said had shaped all her learning on inequality. Or the World Bank including unpaid care roles for the first time, based on research and policy work led by Thalia Kidder.

Such impact is more often drip, drip than earth shattering light bulb moment. Similarly, the ESRC Impact awards went to often long term, efforts to understand and apply insights. The finalists were gobsmacking in their breadth, depth and societal impact.

Who knew that in our very own Oxford backyard we house the award-winning researcher Professor Lucie Culver? Her work ‘Cash for Care’ has has helped over two million girls in 10 African countries avoid contracting HIV/AIDS since 2014. (How did they measure that impact?). Here’s a 5m video summary:

Another Oxford-based winner (of the Outstanding Impact in Society), the Migration Observatory, has become phenomenally influential by simply providing impartial data. In a Britain that was prone to making unfounded, sweeping generalizations about refugees, they set up the first independent source of migration data, “prompting more nuanced media coverage on polarised issues such as the assumption that EU immigration is driven by ‘welfare benefits tourism’”.

And fiscal justice anyone? Professor Michael Levi was runner-up of Outstanding International Impact for his work on illicit financial flows that generated key, actionable insights about the £13billion cost to the UK. Particularly cool is his co-founding of the World Economic Forum Global Agenda Council on Organized Crime, to intervene against professionals that make financial crimes possible, not only frontline criminals.

I was struck by the consistency of what made their research have the impact it did. Impact requires compassion – these researchers  care. They care about the injustice of people dying from cold in the UK (energy poverty research that can benefit 54 million people – who knew?). They care about ensuring our judicial systems are fair and believable by improving – over the course of 25 years (!) – how victims are interviewed. They care about giving ethnic minorities an entrepreneurial chance. They care about being informed about issues that affect many people deeply. Five criteria were mentioned at the awards: sharp – no wastage around definition of theme; fiercely independent – no writing of conclusions beforehand; exceptional quality; deeply relevant and beautifully communicated. Then ‘impact follows as night after day’.

care. They care about the injustice of people dying from cold in the UK (energy poverty research that can benefit 54 million people – who knew?). They care about ensuring our judicial systems are fair and believable by improving – over the course of 25 years (!) – how victims are interviewed. They care about giving ethnic minorities an entrepreneurial chance. They care about being informed about issues that affect many people deeply. Five criteria were mentioned at the awards: sharp – no wastage around definition of theme; fiercely independent – no writing of conclusions beforehand; exceptional quality; deeply relevant and beautifully communicated. Then ‘impact follows as night after day’.

So how is this relevant to Oxfam’s evidence-informed aspiration?

Valuing the long haul. Much of this work rewards dogged long term efforts. Three, five and even 25 year processes of research and applying findings. These were not awards for people who had received funding over the past 12 months but over years and requires a bit more than ‘merely writing a policy brief’, as argued recently by Professor Hilhorst. Or in Oxfam’s case – requires more than publishing simply to be heard.

That’s why ‘big C’ communication has got to be high on our priority list. The prize winners were not just into producing a snazzy infographic (or, dare I say it, blog). They translated what they found into training courses for police (all of them in the UK), into practical programmes and specific policies. They held town hall meetings to share their findings. They invested much time simply listening – to cold citizens, abused girls, maligned victims of crimes, keen entrepreneurs. They set up information centres and put accessible information out there. They knew what a wide communication approach was needed as part of evidence.

That’s why ‘big C’ communication has got to be high on our priority list. The prize winners were not just into producing a snazzy infographic (or, dare I say it, blog). They translated what they found into training courses for police (all of them in the UK), into practical programmes and specific policies. They held town hall meetings to share their findings. They invested much time simply listening – to cold citizens, abused girls, maligned victims of crimes, keen entrepreneurs. They set up information centres and put accessible information out there. They knew what a wide communication approach was needed as part of evidence.

Let’s not be hostile to academics (or make sweeping generalisations) – as long as they in turn recognise that Oxfam brings loads to the table. Joint work would be a win-win. Research grant givers are serious about societal impact – it’s not just a formality in the application process. Thinking in detail about impact pathways gets you not only lots of brownie points in the grant appraisal process but also the Holy Grail of actual impact. The ESRC Award winners showed what was possible. And Oxfam has much to offer the research world – grounded questions, innovative methods, excellent engagement skills, vast networks, access to influentials, direct feeding into advocacy and programming, and sharp analysis.

The awards made me even hungrier to connect with the world of passionate researchers who care about those with the least. There is massive potential. If you want to talk, contact me on iguijt[at]Oxfam.org.uk

July 31, 2017

Where do South Africa’s activists go from here? A Cape Town conversation

My last  morning in Cape Town last week was spent deep in discussion with three fine organizations – two local, one global. The global one was the International Budget Partnership, who I’ve blogged about quite a lot recently. The local ones were very different and both brilliant: the Social Justice Coalition and the Development Action Group. SJC favours a largely outside track, famously organizing local residences in Khaleyitsha township to campaign for decent toilets (see video, below). DAG also works with poor communities and their organizations, but has started engaging with ‘civics’ – often middle class ratepayers’ associations and the like, and with sympathetic officials and politicians. Cape Town’s polarized politics pushes them in these directions, since the Province and City are in the hands of the opposition Democratic Alliance (DA), still seen as largely the party of whites and coloureds, while Kaleyitsha is a black township whose Ward Councillors mostly belong to the ruling ANC. Neither wants to work with the other.

morning in Cape Town last week was spent deep in discussion with three fine organizations – two local, one global. The global one was the International Budget Partnership, who I’ve blogged about quite a lot recently. The local ones were very different and both brilliant: the Social Justice Coalition and the Development Action Group. SJC favours a largely outside track, famously organizing local residences in Khaleyitsha township to campaign for decent toilets (see video, below). DAG also works with poor communities and their organizations, but has started engaging with ‘civics’ – often middle class ratepayers’ associations and the like, and with sympathetic officials and politicians. Cape Town’s polarized politics pushes them in these directions, since the Province and City are in the hands of the opposition Democratic Alliance (DA), still seen as largely the party of whites and coloureds, while Kaleyitsha is a black township whose Ward Councillors mostly belong to the ruling ANC. Neither wants to work with the other.

The reason we were talking is that both organizations feel stuck: the Cape Town city government is not responding to either insider or outsider tactics, with civic groups of all stripes feeling shut out and frustrated. SJC has been unable to get a meeting with the city authorities for over year, ‘participation fatigue’ has set in, and it has given up (for the moment at least) encouraging township residents to file submissions to the budget process, as described in the video.

So, we asked ourselves, where are the chinks of light, and where might a change of tactic/theory of action get some results?

From demand to supply and beyond: South Africa is a bastion of a particular form of civil society activism – organizing CSOs to make demands of the state to supply services, housing, toilets, education, healthcare etc etc. In many countries a big rethink of that model has gone on in recent years, and my conversations in Cape Town suggests it’s imminent here too. Purely demand-led protests aren’t getting anywhere; both organizations reported conversations with harassed officials and politicians with no idea how to meet the demands (there are 3 people in the ‘participation unit’ for the whole city). Others have told them that the money is there, but they just don’t know how to find space in the communities where they can build the toilets that the population is demanding (’we have huge issues with officials not knowing what to do’; ‘I get lost as a Ward Councillor – I don’t know who to talk to’).

From demand to supply and beyond: South Africa is a bastion of a particular form of civil society activism – organizing CSOs to make demands of the state to supply services, housing, toilets, education, healthcare etc etc. In many countries a big rethink of that model has gone on in recent years, and my conversations in Cape Town suggests it’s imminent here too. Purely demand-led protests aren’t getting anywhere; both organizations reported conversations with harassed officials and politicians with no idea how to meet the demands (there are 3 people in the ‘participation unit’ for the whole city). Others have told them that the money is there, but they just don’t know how to find space in the communities where they can build the toilets that the population is demanding (’we have huge issues with officials not knowing what to do’; ‘I get lost as a Ward Councillor – I don’t know who to talk to’).

That suggests a shift in tactics to something like a multi-stakeholder approach – finding a respected institution or individual to bring together the residents, the officials, the politicians, engineers etc to work together (building trust along the way) in search of answers to a problem they can all agree on, such as the need for flush toilets.

Spending more time on hidden power: up to now, the activists have concentrated on visible power (the Council, the designated officials) and invisible power (boosting the self confidence and agency of township dwellers so that they get involved. But they have spent less time really understanding and acting upon ‘hidden power’ – who influences the budget before it reaches the public draft/token consultation stage? Who might the decision makers listen to (academics, former politicians, retired officials) who could amplify the voices of the residents?

Doing that requires a big shift in mindset from seeing the state as a ‘target’ to learning to ‘see like a civil servant/local politician’, appreciating their incentives and constraints, building bridges. That does not mean trying to become their best friend, but to create relationships that balance empathy and tension. It also means being less grudging about celebrating those successes that do occur.

What persuades? Cape Town is very proud of its status as one of the network of 100 ‘resilient cities’ which the Rockefeller Foundation has set up. That provides a point of entry – how to link ‘resilience’ with the need for public participation in decision-making?

But there is a bigger conceptual blockage. Many officials and politicians, in their heart of hearts, still consider places like Khaleyitsha as ‘temporary’ (even though they’ve been there for decades). That acts as a mental block to finding long term solutions like proper toilets, rather than temporary cabins. How to shift the mindset, get the townships’ permanent nature recognized? Until that happens, advocacy is always going to be uphill work.

What disrupts: There were some interesting stories of DA politicians at provincial level being willing to step outside party allegiance, going over the heads of City DA people to work directly with black activists in the townships. That looks worth pursuing. The other thing you can be sure of in South Africa is scandal and disaster, which act as windows of opportunity for shaking things up. Could activists get better at preparing and responding to such ‘critical junctures’, for example the next township flood or corruption story, putting together the research and networks in advance to mobilize in the first hours and days of opportunity?

Lots of ideas, but lots of challenges too. Cape Town’s entrenched social and political polarization means that every act of protest or advocacy risks being reduced to ‘you’re just saying that because you’re ANC/DA’. It’s probably no accident that IBP partners are doing much better in those metros (as South Africa’s big cities are known) that recently acquired coalition governments, which now have to care a bit more about what the voters say.

And here’s the SJC video (10 minutes):

July 30, 2017

Links I Liked

Washington’s corridors of power are looking empty in Donald Trump’s unfilled government: according to The Economist, ‘His lethargy, not Democratic obstinacy, is to blame’.

lethargy, not Democratic obstinacy, is to blame’.

Finding positive outliers on anti-corruption is surprisingly hard, because everyone disputes success stories. Brilliant from Caryn Pfeiffer

What do India’s poor have to say about poverty and aid? First of an annual 10 country ‘Voices of the Poor’ exercise by Globescan with Oxfam India.

Istanbul: egg sized hail stones, flash floods, fires… this is climate change in an overbuilt underprepared city, says Milena Buyum [ht via Alex Evans]

Thoughtful, warts and all profile of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, Liberian president & donor darling

‘Elections in Africa make people feel more “ethnic”.’ Overview of +/- of Africa’s democracies from Nic Cheeseman and a curtain raiser for the Kenyan elections on 8th August.

Is the world really better than ever? Interesting ‘long read’ discussion of the ‘New Optimists’ & their politics

Brilliant Save the Kids video on the bombing of children, starting with you entering your postcode.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers