Duncan Green's Blog, page 110

September 28, 2017

The new Gates Foundation aid report: great at human stories; but where’s the power, politics and mess?

I’ve been reading the new Gates Foundation report, The Stories Behind the Data (lots of jazzy webstuff and graphs of bad stuff going down here – and if you dig hard enough, you can even find a good old-fashioned report to read here). On one level it is exemplary, setting out both an optimistic story of progress, and a warning that this could all be in jeopardy, not least from proposed cuts to aid budgets in the US and elsewhere. The website and graphics are clear and informative, covering 18 of the SDG’s legion of indicators on poverty, health and access to finance. Each of 15 timelines (there’s insufficient data on education, gender and agriculture) shows a fork in the road at 2016 between optimistic and pessimistic projections (here’s HIV). If you’re looking for evidence that aid matters, it’s a good place to start.

optimistic and pessimistic projections (here’s HIV). If you’re looking for evidence that aid matters, it’s a good place to start.

But as I was reading it, I was also struck by what is not included – basically, nearly all the stuff I’ve been thinking about for the last few years. So here’s my X ray of the world according to the Gates Foundation, and what is missing.

Category A – what’s in: Data (lots of data); health; government programmes and budgets; finance; technology; life v death; evidence-based policy making

Category B – what’s missing: Politics; civil and political rights; war and conflict; ‘othering’ and hatred; deal-making and self interest; critical junctures (political or environmental shocks that change what is politically and socially possible); social norms

If you buy this, then isn’t it a problem that so much of the progress in Category A is in fact largely determined by what goes on in Category B? It’s like concentrating on the tip of the iceberg and ignoring the stuff below the waterline.

This thought was triggered when I hit the first country case study, on maternal mortality in Ethiopia. Here’s the timeline:

You don’t need to be an Ethiopia expert to think there’s quite a lot of other things that should be on this timeline, if you really want to understand what happened on maternal mortality: the economy and growth, sure, but also war, revolution; changes of leadership;  civil rights (or lack of them).

civil rights (or lack of them).

Does this matter? I assume that anyone spending the Gates’ money on the ground will be fully aware of all this. As Ros Eyben has documented, aid workers specialize in riding two horses at the same time – a technocratic, project based world of logframes and results, and the real world of messy politics, power, accident and luck. And perhaps leaving all of Category B out of it makes for a better exercise in convincing the public. But if technocrats in head offices start to believe that this is what the world actually looks like (a data and evidence-based rationalist exercise in maximising human wellbeing), then I think they run the risk of designing programmes that won’t work.

I ran the draft of this post past Jonathan Scanlon, Oxfam’s guy in Seattle and got this interesting response:

‘I’ve always wondered why Bill Gates addresses policy and regulatory issues and politics differently at BMGF compared to running Microsoft. When he had a policy issue at Microsoft he fought hard – lobbied, hired lobbyists, donated to politicians and political parties, filed lawsuits, yet on global poverty issues he ties his hands by only funding 501(c)(3) organizations in the US (and their equivalents abroad) and doing some advocacy himself. But he doesn’t fight like he did at Microsoft. Global poverty deserves someone backing a tough way to fight. If building a massive global corporation deserved this, so does poverty.’

For Bill Gates read politicians and ministers everywhere – they get to positions of power by navigating the mess, but too many of them, on arriving at the ministerial hotseat, suddenly go linear and start obsessing on measurement, predictably achievable results, zero risk etc.

Thoughts?

And here’s BillandMelinda’s pitch, summarizing it all in 2 minutes

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=5&v=zBD6m2K9_Dc

September 27, 2017

Are grassroots faith organizations better at advocacy/making change happen?

As part of thinking about how power operates in fragile/conflict states (for the LSE’s new Centre for Public Authority in International Development, CPAID), I’m doing a bit more reading around the role of different kinds of ‘non state actors’. One of the most influential in many fragile/conflict settings are faith organizations, so I finally got round to reading ‘Bridging the Gap: The role of local churches in fostering local‑level social accountability and governance’ from Tear Fund, which describes itself as a ‘Christian charity passionate about ending poverty’.

in International Development, CPAID), I’m doing a bit more reading around the role of different kinds of ‘non state actors’. One of the most influential in many fragile/conflict settings are faith organizations, so I finally got round to reading ‘Bridging the Gap: The role of local churches in fostering local‑level social accountability and governance’ from Tear Fund, which describes itself as a ‘Christian charity passionate about ending poverty’.

The report looks at Tear Fund’s support for grassroots advocacy by its partner in Uganda, the Pentecostal Assemblies of God (PAG).This is part of a wider church and community mobilisation (CCM) process.

‘CCM approaches differ according to the context. However, they all involve the local church congregations participating in Bible studies and other interactive activities together, which catalyse them to work across denominations and with their local communities to identify and address the communities’ needs with their own resources.

As the first step, the church leaders at the denominational level are trained as CCM facilitators. The local church then goes through the ‘church awakening’ phase, which aims to change people’s attitudes to see themselves as all equal before God, to identify the resources they have and to build a vision for working together towards developing the community. The local church then liaises with community leaders and invites the wider community to come together to identify their needs, resources and skills. They then elect a Community Development Committee (CDC) which, with the help of the facilitator, maps community assets and key stakeholders, preparing a vision and action plan. The solutions vary across contexts – sometimes savings groups are formed – and in response to a variety of issues depending on the community’s most pressing needs,  including food security, health, water and sanitation, or livelihoods.’

including food security, health, water and sanitation, or livelihoods.’

With a few tweaks of language, this could have been written by any secular NGO working on similar issues, but I was looking for the special sauce – what’s different about working through the Churches, compared to non-religious partners? Here’s what Tear Fund says:

‘Local churches are trusted

CCM advocacy has proven that local churches are regarded with a high level of trust. They are trusted by their congregations, by the communities in which they are located and by local government.

The trust that the congregation and the majority of the community place in the church was a key driver in motivating participation in the CCM process, the advocacy training and also governance more generally. In Uganda, more than 80 per cent of people are Christian and it became apparent in the research that the church is a trusted authority figure, both by church members and by the wider community. This has led to an increase in citizen engagement in those communities who have completed the CCM and CCM advocacy training. This trust in the church enabled the CCM advocacy process to be established successfully in the community, with good engagement, and for the trainings to be taken on board quickly and effectively.

Participants’ responses revealed the main reason why the church is trusted. Firstly, as many in the community have embedded Christian values, trust derives from shared values. Many people consider the Bible an authority and therefore, where the CCM advocacy included references to the Bible, there was more engagement and take-up.

‘It would have not worked well with a secular NGO: the Bible has teachings, it encourages people to share, people fear God, they know it is God’s language and know they should listen!’ Woman from Arapai, where there was CCM and some advocacy

Secondly, as the church is established in the community and has a good reputation historically, people are willing to

Including changing local government, apparently. From the PAG website

be involved in its initiatives. Thirdly, linked to this is the way in which local church leaders and the church have existing relationships and links within the community. The process therefore did not require starting a new network or building new relationships. Finally, people felt safe to attend as it is a familiar environment for many. This meant that the church could become a ‘school for learning’ (to coin a phrase used in one community). Trust in the church allowed for this knowledge to be accepted and communities to use what they had learnt, as the knowledge had come from a trusted source.

Another key to the success of the engagement was the volunteerism encouraged by the church. Many groups explained that, whereas with NGO programmes the participants would expect handouts, the church is not expected to provide in the same way and people expect to volunteer their time at church. When discussing the motivation behind participating in CCM advocacy, more than 50 per cent of people referred to ‘my church’.

The training included biblical verses about advocacy: this encouraged community members to participate and understand that they have a right as citizens and a mandate to fight for justice, particularly on behalf of the marginalised such as widows and orphans. One hundred per cent of respondents who had had some of the advocacy training indicated that they had been encouraged by the church to attend government meetings, which they would never normally have been keen to do.

Government trusts the church

A key to ensuring increased good governance and accountability is the way in which the government sees the church and therefore the participating communities as trustworthy and honest. The government perceives the church as an important influencer in encouraging the community to obey the government and keep the peace. It is therefore willing to share information through the church, both about government programmes (eg immunisation schemes) and via sensitisation meetings (where government workers share learning on a particular topic, such as HIV prevention). The church is ‘faithful’ and embedded in the community, with a ready audience and an understanding of local issues.

A key to ensuring increased good governance and accountability is the way in which the government sees the church and therefore the participating communities as trustworthy and honest. The government perceives the church as an important influencer in encouraging the community to obey the government and keep the peace. It is therefore willing to share information through the church, both about government programmes (eg immunisation schemes) and via sensitisation meetings (where government workers share learning on a particular topic, such as HIV prevention). The church is ‘faithful’ and embedded in the community, with a ready audience and an understanding of local issues.

‘We trust the church. We have so many organisations and individuals who come but, at the end, they disappear. But the church is there permanently. Even when there are changes in leadership, the church remains.’ Onya George, Regional District Councillor of Akonopeesa, Serere district’

Powerful and convincing stuff. The report acknowledges that things are not so easy when the community is less uni-faith, and that stirring it up with advocacy training might weaken its ‘trustworthiness’ in the eyes of government.

One thing I did wonder about was the use of ‘the Church’ in the singular. My experience of evangelical churches in Latin America is that they sometimes resemble ferrets in a sack, fighting for adherents, rather than cooperating – does that not complicate the effort to build an advocacy movement?

Oh, and in case you’re wondering, I’m a lifelong atheist.

September 26, 2017

Legitimacy: the dark matter of international development

Guest Post by Aoife McCullough, Research Fellow, ODI

Many donors work on the premise that a state can move from fragile to ‘stable’ if its legitimacy is strengthened. Accordingly, there’s a broad donor consensus that interventions in fragile states should include a mix of activities likely to contribute to increased state legitimacy – what the World Development Report 2011 calls ‘restoring confidence’.

In practice, the emphasis on ‘restoring confidence’ often translates into programmes that aim to increase access to services. The suggestion is that improved access to services will strengthen the state/society contract and, state legitimacy will follow. That is why millions of aid dollars have been spent on improving access to services in fragile states: In 2012, 45.4% of total ODA to 50 fragile states was spent on ‘economic foundations and services.’

As with most solutions in international development, it’s just not that straightforward. Here are three problems with the way international development actors currently seek to improve state legitimacy.

Trying to ascertain how a state gains legitimacy is complicated

State legitimacy is based on what people consider as the right way to exercise authority – if the state broadly conforms to those expectations or ‘rightness’, then people will consider the state legitimate. Those expectations are not formed in a one-way process. People’s expectations are, in part, influenced by the history of the state and by the laws and principles that have been negotiated between the state and its citizens over time. That’s not an easy process to influence through an aid programme.

There’s very little evidence for services improving state legitimacy

Recent large-scale cross-country quantitative and qualitative research carried out by the Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium (SLRC) over a period of six years shows that even influencing perceptions of government through service delivery is not straightforward.

SLRC asked almost 9,000 respondents in five countries (Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Uganda and DRC) about access to and satisfaction with services, and about their perceptions of their government. Following the first round of the survey that was carried out in 2012/2013, the SLRC went back to the same people in 2015/2016 and asked them the same questions, enabling a comparison between locations and two points in time. The surveys didn’t measure legitimacy per se, but perceptions of government – an important aspect of the construction of legitimacy – and therefore provide an indication of just how tenuous the link between access to services and state legitimacy is.

SLRC asked almost 9,000 respondents in five countries (Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Uganda and DRC) about access to and satisfaction with services, and about their perceptions of their government. Following the first round of the survey that was carried out in 2012/2013, the SLRC went back to the same people in 2015/2016 and asked them the same questions, enabling a comparison between locations and two points in time. The surveys didn’t measure legitimacy per se, but perceptions of government – an important aspect of the construction of legitimacy – and therefore provide an indication of just how tenuous the link between access to services and state legitimacy is.

The research found that increased access to public services such as health care or education did not significantly change people’s perception of government, in either a positive or negative way. In the aid industry, there is often a worry that delivering services directly through NGOs will result in delegitimizing the national government. The findings from the surveys show that service delivery by non-government agents such as NGOs did not necessarily detract from people’s perceptions of government. What appears to be more important in influencing people’s perceptions of government is the way that services are delivered and experienced.

If people have access to grievance mechanisms or are aware of opportunities to influence decision-making about a service – through community meetings for example – their perceptions of government are more likely to be positive. However, the effect of having access to a grievance mechanism was not strong – in fact, the type of experience that had the most influence on perceptions of government was a negative experience.

This finding raises the uncomfortable possibility that delivering services that create problems for people may be more damaging to perceptions of government than not delivering any services. In fragile states, it is probably impossible to deliver a service that does not create a problem for service users in some form.

The survey also found that the wider political context influenced perceptions of government. In three of the countries, significant political transitions took place that had a clear impact on how people perceived their government. For example, in Sri Lanka, a northern-supported government was elected in 2015 and the percentage of respondents who thought that central government cared about their opinions grew from 44% to 65%. But as most aid programmes are not designed to facilitate significant political transitions, this finding highlights the extent to which an aid programme is likely to have a limited impact on state legitimacy.

Legitimacy is hard to pin down

The only time that state legitimacy becomes a tangible, identifiable phenomenon is when a state loses its legitimacy in a particularly visible way. It’s not until people begin to act on their disbelief in the state that its lack of legitimacy becomes clear.

Yet it would be wrong to assume that the absence of revolt indicates a legitimate state. The cost of revolting against a state is extremely high and many people living in states that no longer hold legitimacy simply choose the less costly option of cooperating.

If legitimacy is so hard to pin down, can donors meaningfully support its development? Donors can use proxies –  like perceptions of government – to measure the impact of their activities on state legitimacy. But citizens’ perceptions of government are only part of the mosaic that makes state legitimacy. Claire McLoughlin’s suggestion of six ways in which services influence state legitimacy is a great overview of the wide range of processes that contribute to legitimacy. But it’s not clear how an aid programme would track impact on some of these processes. For example, one of the factors that influences how a service might influence state legitimacy is though what McLoughlin identifies as the state’s ‘legitimacy reservoir’, i.e. the foundations of legitimacy making in a state. Any effects that service delivery might have on the state’s legitimacy reservoir will be difficult to identify within the timeframe of most aid programmes. In any case, most aid programmes don’t have the capacity or budget to do the kind of monitoring and evaluation necessary to measure impact across such a diverse set of processes.

like perceptions of government – to measure the impact of their activities on state legitimacy. But citizens’ perceptions of government are only part of the mosaic that makes state legitimacy. Claire McLoughlin’s suggestion of six ways in which services influence state legitimacy is a great overview of the wide range of processes that contribute to legitimacy. But it’s not clear how an aid programme would track impact on some of these processes. For example, one of the factors that influences how a service might influence state legitimacy is though what McLoughlin identifies as the state’s ‘legitimacy reservoir’, i.e. the foundations of legitimacy making in a state. Any effects that service delivery might have on the state’s legitimacy reservoir will be difficult to identify within the timeframe of most aid programmes. In any case, most aid programmes don’t have the capacity or budget to do the kind of monitoring and evaluation necessary to measure impact across such a diverse set of processes.

Perhaps it’s time to be less ambitious

Robert Blair first used the term ‘dark matter’ to describe legitimacy when attempting to measure it in a field experiment in Liberia. If defining and measuring legitimacy is proving too tricky for social scientists, maybe it’s time to admit that trying to increase state legitimacy with aid programmes is too ambitious. State legitimacy is an important concept and decision makers for development programmes need to be cognizant of the extent to which a state may be legitimate or not. But by treating legitimacy as an outcome that aid programmes can influence and measure impact on, the development industry is fooling itself.

There is a way that the development industry can engage more effectively on the issues of legitimacy. State legitimacy is a constantly evolving process that both state actors and non-state actors engage in to produce narratives about the state. An important function of these narratives is to justify who benefits from the state and who is excluded. Service delivery is one of these functions about which legitimating narratives are produced. For example, a legitimating narrative is currently being produced in the UK justifying why certain people need to pay for the NHS. Instead of aiming to increase state legitimacy through service delivery, the development industry would be better off focusing on increasing the legitimacy of inclusive service delivery in countries where they are working to improve service delivery. This is a sensitive process that needs to take into account overall narratives of state legitimacy. In fragile states, where a political settlement is contested with violence, it will be especially tricky. However, by focusing on legitimating narratives for inclusive service delivery, aid agencies can at least aim for something that is tangible and measurable.

And ODI asked me to plug two new papers on ‘fragile and conflict-affected situations': one on tracking change via panel surveys; one on ‘How to support statebuilding, service delivery and recovery‘.

September 25, 2017

Should the World Bank become more adaptive by weakening its safeguards?

The World Bank wants to become more agile, to speed up its grant/loan-making, be less bureaucratic, leap on the

Philippines safeguards protest

‘adaptive management’ bandwagon etc. In its rush to change direction, it hasn’t had too many discussions with NGOs, so I thought I’d raise some of the issues on the blog. Perhaps the lack of discussion is because the Bank sees NGOs as a potential roadblock to reform. By insisting (and getting agreement) on a range of ‘safeguards’ on issues such as consultation or impact assessment, we are seen to have slowed down Bank procedures (and it’s probably true, to some extent, though we’d argue for good reason).

I spent an hour on the phone with some Oxfam colleagues last week kicking these issues around – I do like conversations about trade-offs, tensions and shades of grey. At the end of it we agreed I’d consult the FP2P hivemind for advice.

So who could possibly be against agility? Well, me, in some cases. What if speed comes at the expense of properly consulting local communities, or doing a rigorous impact assessment before you build the road or the hydroelectric dam on their land? One person’s bureaucracy can be another’s livelihood protection.

First of all, what’s the Bank’s motive for wanting to be more ‘agile’? Is it to speed up disbursements, recognize that flexibility and adaptive management is the key to working in complex systems, or to reduce the heavy transaction costs on staff and partners of all its procedures (see DFID’s transition to Smart Rules)? It’s probably all three, but the balance varies depending on who’s talking. It’s worth bearing in mind because different motives have different consequences for how ‘agility’ is interpreted.

From the point of view of systems thinking, this is about adaptive management: you can’t completely understand the system in advance, you will learn more about it as you go, and in any case it keeps changing. So what matters is building in feedback loops and mechanisms to respond/adapt your work as you learn by doing/failing – compliance approaches and tickbox thinking are so last year. In adaptive management you’re only as good as your feedback, but what makes for a good feedback loop?

Oxfam itself is keen to become more agile, and where we trust the Bank, we ought to support it to do likewise. But the upfront safeguards are there for a reason, to understand if a project is actually viable, to ensure appropriate resources are available for managing risk etc, but also partly because of lack of trust. If you don’t trust an institution or its officials, you pile on the regulations and procedures to try and stop them doing bad stuff.

Trust also determines how we see the role of the recipient government. If CSOs trust the government, they will support devolution of power and decision-making – having a responsive, accountable government in charge is infinitely preferable to a Washington bean counter, however well intentioned. But if the government has a track record of brutalising the poor, then we want to keep strong oversight in the Bank’s hands, where civil society can at least exert some influence over what happens.

And some of the things NGOs care about do not lend themselves to fast-and-funky startup-style agility. Big projects in infrastructure or mining need to consult communities, find ways for them to participate in a genuine way in making sure the project helps (and doesn’t harm) local people. That takes time – shoving a load of data on a website may look like participation, but is more likely to be lip service.

And some of the things NGOs care about do not lend themselves to fast-and-funky startup-style agility. Big projects in infrastructure or mining need to consult communities, find ways for them to participate in a genuine way in making sure the project helps (and doesn’t harm) local people. That takes time – shoving a load of data on a website may look like participation, but is more likely to be lip service.

That links to a second point. Adaptive Management sounds good – but who decides what needs to be adjusted and adapted? If it’s just some technocrats in Washington, what is to say the adapted project will help local communities more than the original?

The optimal balance of agility and procedural rigidity also depends on the topic. If the Bank’s dollars are going to help build a dam, a road or a gigantic mine, then if things go wrong, they may well be irreversible. That argues for sticking to the current system of high levels of upfront analysis and safeguards. If the project is less immediately disruptive, and can be tweaked before it does lasting damage, then adaptive management based on the right kinds of feedback loops could be a better option.

It also depends on the government receiving the loan. If it has a track record of accountability and responsiveness to community needs, then adaptive management and devolution of decision making could make a lot more sense than if it routinely crushes feedback (and people) it doesn’t like.

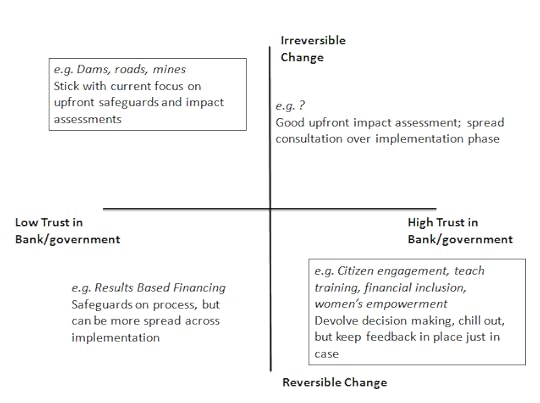

Given my fondness for 2x2s (though to my dismay, not all my colleagues’), you may already have guessed where this is going. I’m trying to construct a 2×2 which helps frame the situations in which you would want to stick with the current system of upfront safeguards, and others in which it would make more sense to jump into a more adaptive, iterative approach. How about this?

High irreversibility/low trust (due to track record of Bank or Government): Stick with current approach

Examples: Dams, roads, extractives, PPPs that saddle governments with decades-long contracts

High Irreversibility/high trust: Still needs proper impact assessment, but maybe spread consultation and participation out more into the implementation phase

Examples: ?

Easily Reversed/low trust: The safeguards need to be on process – how can we be sure the consultation is genuine, and the project/government/Bank will respond to the results?

Examples: results based financing

Easily Reversed/High Trust: get stuck in, pass power and decision making to local actors, keep an eye on feedback loops to make sure they are working

Examples: Citizen engagement; teacher training; financial inclusion; women’s economic empowerment

Thoughts? Anyone got better suggestions for the axes?

September 24, 2017

Links I Liked

Nice cup of Nambian covfefe anyone? Ht Calestous Juma

Clickbait and impact: how academia has been hacked, Nice piece on THAT ‘in praise of colonialism’ Third World Quarterly paper

Strategic litigation is getting going on climate change: San Franciso becomes the 1st major U.S. city to sue the fossil fuel industry for knowingly causing it.

How I lost my past. Beautiful and poignant exploration of the contrast between official and personal histories from inequality guru Branko Milanovic, who grew up in Yugoslavia

How I lost my past. Beautiful and poignant exploration of the contrast between official and personal histories from inequality guru Branko Milanovic, who grew up in Yugoslavia

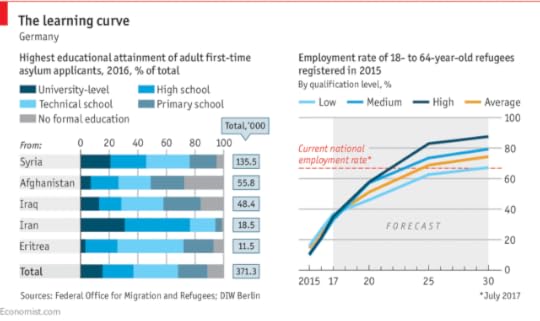

Germany has taken in over 1.2 million refugees over past 2 years and is integrating them (jobs, education).

The American Dream under threat. Oxfam rented President Trump’s childhood home so that refugees could tell their stories. Genius.

Black Lives Matter activists debate with Trump supporters. And get somewhere. Extraordinary and life affirming – make sure you watch this

September 21, 2017

What does Artificial Intelligence mean for the future of poor countries?

What do the multiple overlapping new technologies currently breaking in tsunamis over the world’s economies and societies mean for the future of low and middle income countries (LMICs)? Last week I went along to a seminar (Chatham House Rule, so no names) on this topic, hoping for some interesting, preferably optimistic ideas and examples. I came away deeply, deeply worried. Houston we have a very substantial problem.

The conversation took place in a hipster warren (lot of beards per square metre) in London’s ‘silicon roundabout’ (yes, that’s British humour for you). The skype crashed during the first presentation from East Africa and we had to give up on it (but here’s what they probably would have said). Turned out to be an apt metaphor for what followed.

What technologies are we talking about? The OECD has kindly pulled them together on this mind boggling chart.

The tech revolution will affect LMICs on at least four levels:

Jobs and the productive economy

Private consumption of goods and services

Government service delivery

Rights and Voice

I found different balances of optimism/despair on the four. At the optimistic end, there are lots of apps and potential leapfrogging (eg diagnosing disease or mobile banking) which show real promise in bringing goods and services to hitherto excluded consumers. E-government could be a lot more responsive and less corrupt than the analogue variety.

So much for the upside, which was completely eclipsed (for me at least, we had a few techno-optimists in the room, exhibiting what one speaker called ‘the TED talk view of the world’) by the dark side. On Rights and Voice, state surveillance, private control of data, and general invasion/manipulation of our lives is becoming apparent much faster than the potential positives of cyber-activism.

But what really worried me was the economic impact of the new technologies. In particular, their impact on the way countries have historically moved from poverty to prosperity. An excellent paper by Shahid Yusuf of CGD and George Washington University sets out a gory prognosis that AI will kick away the ladder of development, under the striking subhead ‘will there be new jobs or no jobs?’:

‘There are those who believe that technological change will be a gradual process as in the past allowing institutions and labor markets ample time to adjust. The optimists are of the view that although automation, AI, and other technologies that are in the wings will in time eliminate a swathe of jobs, the pace of automation is likely to be slow and new occupations will appear to take the place of the ones that disappear as was the case in the past—assuming of course that economic growth is robust. Past industrial revolutions gave rise to similar fears that proved to be unfounded.

Could it be different this time around? Those who subscribe to the precautionary principle maintain that the pace of  technological change has quickened making it harder for markets and institutions to make timely adjustments. The better-paid jobs that might materialize will require higher levels of cognitive, non-cognitive, and technical skills that are not plentiful in emerging economies and will accumulate slowly. Many emerging economies are currently coping with a large overhang of unemployed and underemployed workers and urgently need to ramp up employment in manufacturing and tradable services.’

technological change has quickened making it harder for markets and institutions to make timely adjustments. The better-paid jobs that might materialize will require higher levels of cognitive, non-cognitive, and technical skills that are not plentiful in emerging economies and will accumulate slowly. Many emerging economies are currently coping with a large overhang of unemployed and underemployed workers and urgently need to ramp up employment in manufacturing and tradable services.’

His conclusion? ‘Export led growth of the sort that created the East Asian legend of the 20th century could be a thing of the past….. This includes industrialized economies that have relied on the exports of manufactures and participation in global value chains—i.e. the Malaysias, Polands, and Thailands—as well as other economies—the Pakistans, Egypts, and Honduras—that are at earlier stages of industrialization.’

So the most successful ladder of development of the last 70 years – low skill, labour intensive industrialization – looks like to be kicked away. 5 million women in Bangladesh currently working in the a garments industry that, for all its flaws, has transformed their lives (and accounts for 80% of Bangladesh’s exports), will probably be replaced by robots, located nearer the consumer markets (no need to make T shirts in Bangladesh if cheap labour is no longer necessary).

Indian production line.

Yusuf thinks some countries can find alternative paths to development through natural resources, services, tourism or migrant remittances. For the rest, the outlook is grim.

The usual policy responses seem terribly inadequate to threats on this scale: A few cool apps really aren’t going to provide jobs for that number of people; trying to retrain huge populations of low skilled workers for high tech jobs, even if education systems are up to it, is running up a down escalator – robots and AI are likely to upskill faster than people.

Another commonly proffered response is a Universal Basic Income – crudely, the state taxes the robots, redistributes the income to the people, and we will all have to learn to enjoy our leisure. But it is easy to imagine other, more dystopian, political settlements between elites and robots. Jobless growth and rising inequality can lead to reforming governments, populist manipulators or repressive crackdowns (aided by new surveillance powers – according to last week’s Economist, China used facial-recognition technology to catch 25 criminal suspects at a beer festival, one of whom had been on the run for a decade).

Discussions about this topic usually divide between the optimists, who cite the Luddites and compare fears of technology to Malthusian anxiety about mass starvation through population growth, and people who say that, as with Climate Change, this time is different. After last week, I’m definitely closer to the second camp, even compared to this post from March. Thoughts from a slightly more optimistic angle here.

September 20, 2017

Two top authors compared: Hossain on Bangladesh and Ang on China

OK, so this week I’ve reviewed the two important new books on the rise of China and Bangladesh.

OK, so this week I’ve reviewed the two important new books on the rise of China and Bangladesh.  Now for the tricky bit – the comparison.

Now for the tricky bit – the comparison.

The books are very different in their approach. Where Yuen Yuen Ang focuses on the ‘how’ in China, Naomi Hossain is more interested in the ‘why’ in Bangladesh.

Hossain traces the ‘why’ to the critical junctures that littered Bangladeshi’s creation, especially the appalling famine of 1974, and its impact in shaping elite beliefs and norm. Collective trauma created a ‘moral economy’ of protecting the people from climate, shocks and hunger (an ‘anti famine contract’).

By contrast, Yuen Yuen Ang doesn’t talk much about what’s going on inside Chinese leaders/officials’ heads (other than greed). For her, the institutional process to bring about growth and development is all about incentives and rationality, while Hossain is all about ideas and norms.

So what I would dearly love to see is the two of them forming a dream team to swap countries (or methodologies), because I want to know more about the missing ‘why’ in China, and the ‘how’ in Bangladesh. The traumatic chaos, bloodletting and famine of Maoism must have had at least as profound an impact on China’s decision makers as the events of the 1970s in Bangladesh. And Ang could help Hossain more fully explain the alchemy by which a chaotic and ineffective government somehow gets officials to do good things (or at least not get in the way). I’d also like Hossain to take a look at the gender aspects of China’s rise – almost entirely missing from Ang’s book.

Yuen Yuen Ang

But what about the authors? Purring over these two books got me thinking

Naomi Hossain

about the role of ‘bicultural’ writers. Naomi is a British Bangladeshi, who by her own admission speaks indifferent Bengali, but that means she has a foot inside and a foot outside the Bangladesh story, and maybe that is an asset in detecting and understanding both the subtleties of what is context specific, and how it reflects on broader debates. That might also help avoid the tendency among US and European authors to interpret the world in terms of their own country histories (eg assuming that the purpose of development is to achieve the American Dream in all countries – a la Acemoglu and Robinson).

Now I realise talking about other people’s ‘positionality’ is a minefield, so I contacted both authors. Here’s what they said:

Yuen Yuen Ang:

‘Your point about bi-culture scholars is spot-on. And I don’t see that it’s ever been raised. It would make a fabulous discussion, since much of development studies is tripped by cultural blindspots.

The difference between me and Naomi et al is that I am tri-culture or even quad-culture (Chinese, Singaporean, American, British), making me an unrooted cultural nomad. As a Singaporean Chinese, in China, I’m regarded as a foreigner and sometimes treated with suspicion, even though I’m ethnically Chinese, and in the US, I’ often annoyingly asked “Which part of China do you come from?” When doing fieldwork in China, I can pass off as Chinese because of my appearance and language, but this is distressing because I’m obliged to behave like a native and respond correctly to all social cues, or risk offending locals. Finally, in Singapore, as I’ve been away for too long, I am not local enough. In short, I am foreign everywhere I go.

But as a result of existing in the crevices of cultures, I see the Chinese context through Western eyes and the Western context through Chinese eyes. Forced to always adapt to my surroundings, I take nothing for granted. Hence, I notice things that my Chinese assistants will regard as normal/boring and not worth a thought.’

Naomi Hossain:

‘Yes I completely agree that a partial insider perspective brings some advantages. The benefits of distance with knowledge I suppose. In my case I would probably have not been quite so interested in famine had I not had an Irish mother with a strong nationalist streak who never forgot the famine or what the British did (or didn’t do!).’

knowledge I suppose. In my case I would probably have not been quite so interested in famine had I not had an Irish mother with a strong nationalist streak who never forgot the famine or what the British did (or didn’t do!).’

Adding Hossain and Ang to my list of personal development gurus made me take another look at the longer list – and a lot of them exhibit something like biculturalism. Ha-Joon Chang (South Korea), Matt Andrews (South Africa) and Amartya Sen (India) are more rooted in their countries of origin, but have long since joined international academia; Dani Rodrik clinks firmly to his Turkishness.

Which suggests that promoting diversity in university faculties, conference panels and all the rest is not just a tokenistic response to colonial guilt, but the best way to get a greater understanding of what is going on in the world. Pretty obvious, when you think about it. As Alice Evans from Kings College, London, commented on the Hossain Review:

‘Naomi is a British Bangladeshi, with long-standing links, interactions and in-depth knowledge of Bangladesh. She has family, friends, [or, more dryly] ‘multiple data points’. She knows more than someone like me could ever know through a few one off trips. If Development Studies remains dominated by white old men from the Global North, we blinker ourselves to these brilliant insights. Building more inclusive research, funding, publishing, conferences etc. is absolutely cardinal to enhancing our understanding of development.’

Thoughts?

September 19, 2017

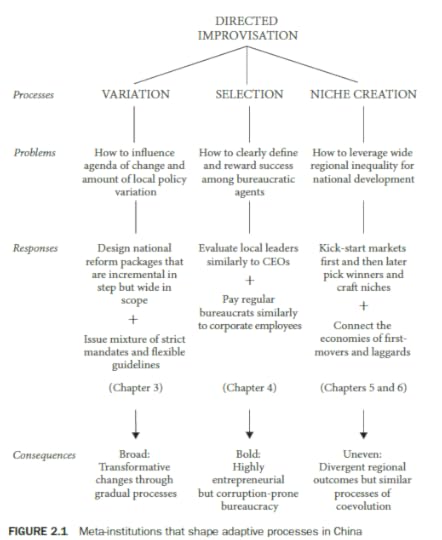

Book Review: How China Escaped the Poverty Trap, by Yuen Yuen Ang

Following on from yesterday’s book review on an account of Bangladesh’s success, here’s a great book on another developmental superstar – China.

The macro-story on China is well known, but always bears repetition. Emerging from the carnage of the Mao era,  China in 1980 had a GDP of $193 per capita, lower than Bangladesh, Chad or Malawi. It’s now the world’s second largest economy, with a thirty fold increase in GDP per capita, based on a textbook-defying combination of one party Communist state and capitalism – in the words of one tongue in cheek official ‘no capitalist state can match our devotion to the capitalist sector.’

China in 1980 had a GDP of $193 per capita, lower than Bangladesh, Chad or Malawi. It’s now the world’s second largest economy, with a thirty fold increase in GDP per capita, based on a textbook-defying combination of one party Communist state and capitalism – in the words of one tongue in cheek official ‘no capitalist state can match our devotion to the capitalist sector.’

Success on this scale inevitably finds many intellectual fathers claiming paternity – China is variously portrayed as a victory for a strong state; free markets; experimentation and for central planning. How China Escaped the Poverty Trap blows the conventional explanations away, drilling down into what actually happened, reconstructing the history of different cities and provinces through years of diligent research.

This book is a triumph, opening a window onto the political economy of China’s astonishing rise that takes as its starting point systems and complexity. Its lessons apply far beyond China’s borders. The author, Yuen Yuen Ang (originally from Singapore) is Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Michigan.

Ang starts with a classic developmental chicken and egg problem – which comes first, good institutions or economic prosperity? Different camps within academia and the aid business urge developing countries either to ‘first, get the institutions right’ or ‘first, get growth going’ – and then the rest will follow.

Using China as an elephant-sized case study, Ang takes a systems sledgehammer to this kind of linear thinking, and argues that development is a ‘coevolutionary process’. Institutions and markets interact with and change each other in context-specific ways that change over time. The institutions that help to achieve take off are not the same as the ones that preserve and consolidate markets later on.

Perhaps her most explosive finding is that for countries just at the start of their development trajectory, so-called ‘weak’ institutions are often better than ‘strong’ ones. The weak/strong description is imposed by experts from already developed countries who conclude that their institutions are obviously the ‘strongest’, since their countries are the richest. Echoes of Ha-Joon Chang’s work on the history of trade policy here (and he provides a fulsome plug for the dust jacket).

It’s impossible to do justice to the book in a brief review, but here’s a taster:

Firstly, there are three distinct patterns to China’s take off: the changes made by the state are broad, bold and uneven. Broad in that the state makes changes across the whole economy: she has little time for Dani Rodrik’s attempts to identify specific bottlenecks and tackle them one at a time – that is thinking about the economy as a complicated, rather than a complex, system. Bold in that when the state changes direction, it does so big time, and the whole country, or at least its 50 million civil servants, jump and do whatever it takes to achieve the new goals. Uneven because the changes play out differently according to time and place within China, and the leadership is happy with that.

Secondly, to explore China through the lens of complexity, she unpacks three signature processes of co-evolution, summarized in the graphic:

Variation: how does the system throw up alternatives and options to deal with particular problems?

Selection: how does it select among the variants to form new combinations?

Niche Creation: how does it craft new, distinct and valuable roles within the system?

China’s answer to the variation question is a fascinating one. The phrase ‘one party state’ conjures up an impression of a regime intent on command and control. An autocracy like China has plenty of red and black lines (don’ts and dos), of course, but what Ang reveals is a third tier – deliberate ‘directed improvisation’- a ‘paradoxical mixture of top-down direction and bottom-up improvisation’. The state sets broad, and often very vague, parameters and then it is up to officials to improvise within them, often coming up with solutions and innovations that astonish the big cheeses in Beijing. I love this phrase, and it could easily become as prevalent and useful as Peter Evans’ ‘embedded autonomy’ to describe the technocracy of developmental states.

She paints a picture of millions of study groups of civil servants poring over the latest Delphic utterances from the Central Committee (e.g. ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’), trying to work out what they can get away with, then entrepreneurially beavering away in responses. She has a partial explanation of why the vague rhetoric of leaders has such a galvanizing effect on officials – she doesn’t touch on the stick – the potentially lethal consequences of getting things wrong/overstepping the new line.

But she graphically demonstrates the carrot – officials on misery wages (the state did not have the capacity to pay properly) were allowed/encouraged to take a cut of any economic activity they could generate. Corruption in the form of ‘profit-sharing’ by officials was an integral part of the model (Ang even worries that the current crackdown could hamper further progress). More broadly the state operates a decentralized ‘franchising mode’, with local government at various levels keeping much of the proceeds of growth.

She shows that China did not follow the East Asian tiger route of highly technocratic ‘developmental states’ ‘picking winners’, not least because of a chronic shortage of technocrats – under Mao, anyone showing signs of technical expertise was branded a capitalist running dog (a term we really need to start using again). Instead primitive accumulation – the first steps on the road to take off – built on what China had in abundance: social networks. Every department and senior official was required to hustle for investment from friends, relatives and contacts, and incentivised with juicy bonuses.

That initial open season led to a flood of chaotic, unplanned primitive capitalism and plenty of graft. Over time both

Shanghai

the chaos and the graft changed: Once economic activity was under way, the state started to regulate and shape, becoming more interventionist about encouraging things like complementarity of industries and specialist clusters as the economy progressed; corruption moved from petty (apparently involving lots of free meals for officials) to the big money variety, hogged by senior figures.

The detail is often fascinating – the history of a single city in Fujian; the way she gets hold of and compares performance criteria for township leaders in Shanghai in 1989 v 2009, showing how an initial overwhelming emphasis on economic growth has transformed into a laundry list of political, social, environmental as well as economic targets that no human can possibly meet. Is the model starting to creak?

And then in her final chapter, she leaves China and briefly applies her co-evolutionary analysis to trade in late Medieval Europe, taxation in 19th C United States and – wait for it – the rise of Nollywood as Africa’s global cinema hub. Which brilliantly shows that aspects of her analysis of China can apply more broadly – clear links to the Doing Development Differently movement, which she name checks (DDD guru Lant Pritchett gave her a glowing review).

I’m running out of space. I give up. Just read the book. (or if you like podcasts you can listen to the author being interviewed by Alice Evans)

And what does all this mean for development organizations? She won a Gates Foundation-sponsored ‘New Horizons’ prize for her essay on the future of aid, so I will just have to read it and get back to you.

Tomorrow, the fun bit – comparing the two books and their authors

September 18, 2017

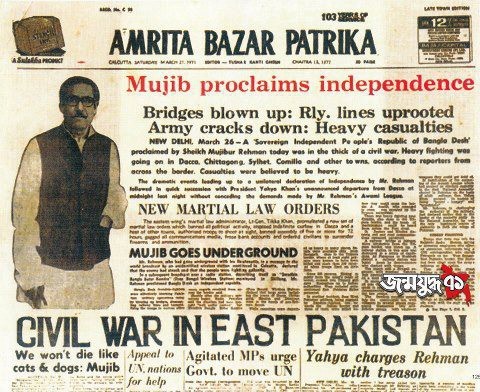

Book Review: The Aid Lab: Understanding Bangladesh’s Unexpected Success, by Naomi Hossain

Over the summer I read a few absolutely brilliant books – hence the spate of book reviews. This week I will cover two new studies on development’s biggest recent success stories – China, but first Bangladesh.

How did Bangladesh go from being a ‘basket case’ (though ‘not necessarily our basket case’ – Henry Kissinger, 1971)  to a development success story, claimed by numerous would-be fathers (aid donors, NGOs, feminists, microfinanciers, low cost solution finders)? That’s the subject of an excellent new book by Naomi Hossain.

to a development success story, claimed by numerous would-be fathers (aid donors, NGOs, feminists, microfinanciers, low cost solution finders)? That’s the subject of an excellent new book by Naomi Hossain.

The success is undeniable. Per capita income is up to $2780 from $890 in 1991 (PPP terms). Today, that economic progess is built on 3 pillars: garments (80% of exports, 3m largely female jobs), migration (remittances = 7-10% GDP, about 9m workers overseas, mainly men) and microfinance (which has been used by about half of all households).

But perhaps even more interesting, social progress has outstripped economic growth. Infant mortality down from 258/1,000 in 1961 to 47 in 2011; women were having 7 kids in 1961 and are now having 2. In Hossain’s words (she writes well) ‘Bangladesh is the smiling, more often than not sweetly female, face of global capitalist development. Better yet – she often wears a headscarf as she goes about enjoying her new economic and political freedoms, signalling that moderate Islam can couple with global capitalism.’ (And yes, she does acknowledge that there is still a lot of hunger and deprivation).

The ‘how’ of Bangladesh’s transformation is reasonably well known. What interests Hossain is the ‘why’. It certainly isn’t down to good governance – ‘it has never been obvious why an elite known best for corruption and violent winner-takes-all politics should have committed its country to a progressive, inclusive development pathway.’

Hossain’s argument is powerful: it all comes down to five traumatic years in the early 1970s, when a massive cyclone was swiftly followed by a brutal war of independence from Pakistan, and that in turn was eclipsed by a horrific famine, in which something like 1.5 million people died. ‘A famine so soon after independence caused a massive crisis of legitimacy for the government, whose overthrow a year later was seen as an expression of the loss of this legitimacy.’

Hossain’s argument is powerful: it all comes down to five traumatic years in the early 1970s, when a massive cyclone was swiftly followed by a brutal war of independence from Pakistan, and that in turn was eclipsed by a horrific famine, in which something like 1.5 million people died. ‘A famine so soon after independence caused a massive crisis of legitimacy for the government, whose overthrow a year later was seen as an expression of the loss of this legitimacy.’

The traumas of the 1970s left a legacy of a political system that, for all its thievery, accepted the moral economy of protecting the people from climate, shocks and hunger (an ‘anti famine contract’). How it achieved this is partly down to other aspects of the Bangladesh story:

Geopolitical/strategic irrelevance: this meant that aid technocrats were not being constantly over-ruled by their political masters, allowing Bangladesh to become the ‘Aid Lab’ of the title.

The lack of entrenched elites: Independence created a country whose nascent elite was still connected with the countryside, farming and normal people and (for all its venality) showed a ‘strong meritocratic streak’ and a faith in the importance of education. Very different from the caste-based paralysis of neighbouring India.

No natural resources: since money wasn’t coming out of the ground, Bangladesh was forced to base its economic progress on its people – a bit like South Korea or Japan (seen as a ‘touchstone’ for its development model)

A breakdown in patriarchy: the war of independence exposed the failure of traditional patriarchy to protect

Dhaka, Bangladesh. 18th July 2012 — Women celebrate and show the peace sign after the announcement of the Higher Secondary Certificate after being published in Bangladesh. — The results of the Higher Secondary Certificate (HSC) and equivalent examinations were announced with an average of 94.41 percent examinees who took part in the Higher Secondary Certificate (HSC) and equivalent examinations from five overseas centres

women – there were 200-400,000 rapes and 25,000 forced pregnancies – while women signed up en masse for workfare schemes during the famine . The ‘woman issue’ was dragged irrevocably into the sphere of public policy and has stayed there ever since.

One quibble: I would have liked to see more of a discussion of the relationships between politicians and civil servants. One of the tricks achieved by Japan, South Korea and other ‘developmental states’ has been to insulate technocratic officials from the grasping hands of politicians, allowing chaotic politics to coexist with an effective state – what happened in Bangladesh?

Given this analysis, calling the book ‘The Aid Lab’ seems a bit misleading – the Bangladesh story is much bigger than that (for example the garments boom, the migration bonanza and arguably the transformation in gender rights had very little to do with aid). Hossain herself says she doesn’t much like the title. But the chapter on aid is interesting, highlighting the combination of donor pressure and government resistance that produced economic policies that in many ways were ahead of their time (eg cautious macroeconomic policy, labour-intensive industrialization, but resisting World Bank pressure to privatize grain procurement, overriding patent protection on essential drugs, along with the focus on women’s empowerment, experimentation and innovative solutions like using 200,000 community health workers to strengthen the healthcare system).

The book ends on the big question: can ‘Golden Bengal’ continue to develop? Hossain argues that Bangladesh is coming to the end of this phase of its development and needs to address some of the weaknesses of its model: in economic terms, its excessive dependence on low end garments and migration leave it vulnerable to shocks; in social

The climate frontline

terms, its fragmented patchwork of state and NGOs is going to struggle to move on from basic primary provision; politically, ‘individual empowerment has rarely, to date, aggregated to institutionalized forms of collective power.’ Hanging over everything else is the menace of climate change – acute in the case of low lying, flood prone Bangladesh as we are seeing right now.

And then there’s the question of memory – as the traumas of the 1970s fade, will new generations of leaders buy into the programme? Already, Bangladesh seems to be drifting towards a one party state under the Awami League, reducing the government’s accountability to the people.

This matters for Bangladesh and more broadly because, as Hossain concludes ‘As an early exemplar of life in an era of high globalization and accelerating climate change, Bangladesh demonstrates that the political foundations of human development, and the priority of a functioning state, must be protection against the crises of subsistence and survival.’

September 17, 2017

Links I Liked

Handy acronyms for online reviews (h/t Shit Academics Say)

The awesome Gates Foundation lobby machine went into overdrive to defend aid budgets last week, with a report on past progress in 18 areas now in peril, Bill in the Guardian saying they are lobbying Congress rather than wasting breath on the President and Melinda talking to the FT (video)

Owen Barder kept us up to date on policy incoherence for development: British Ambassador lobbies Bangladesh government to let British American Tobacco off the hook for £170m in unpaid VAT.

Meanwhile a US-Africa summit on energy (and Power Africa) is cancelled because so many African participants were denied US visas.

In the US, a cop pulls over a black driver for failure to signal, walks to his car with his gun drawn. Mistake, on balance

Another sharp Save the Kids video, this time on UK’s unforgiveable arms sales to Saudi’s war in Yemen (policy incoherence again, but more bloody)

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers