Duncan Green's Blog, page 114

July 13, 2017

How Does the Aid System need to Change? Reflections from the OECD’s new aid boss

Charlotte Petri Gornitzka took over as chair of the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee last October, and from her new  vantage point, reflects on the necessary evolution of the aid system

vantage point, reflects on the necessary evolution of the aid system

For the aid system, the SDGs call for transformation rather than “business as usual”. Everybody is talking the talk but how ready and willing are we to change our own ways of working to enable the transition and crowd in the actors who will play the greater part of delivering on the SDGs?

My own organization epitomises the challenges we face. I chair a committee within the OECD that was set up in a dualistic world in which rich countries extended aid to poor countries, mainly through state-to-state co-operation, but since then the world has become more pluralistic and the development community more diverse. Today many people live in middle income countries (like India, Brazil and Turkey) that both receive and extend development assistance, and an increasing share of aid comes from private foundations and donors outside the OECD.

So does that make the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) a relic of the past? Well, my job is to prove you wrong if that’s what you think. All institutions must constantly evolve to stay relevant. With the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in place we need to speed up this evolution. At last week’s DAC meeting, members agreed to embark on a reform process to make sure the DAC delivers for the SDGs.

Other international institutions face similar challenges. A week ago, the UN Secretary–General Antonio Guterres presented his plan to reposition the UN development system. This consists of 38 concrete ideas built on eight principles. In particular I welcome the principles of accelerating the transition to implementing SDGs, focussing on financing for development and developing a new generation of UN country teams tailored to the specific needs of each country.

The reform of the DAC will be about adapting to the SDGs and increasing its relevance in a changing context. Let me give three examples of how I see the DAC modernising and adapting:

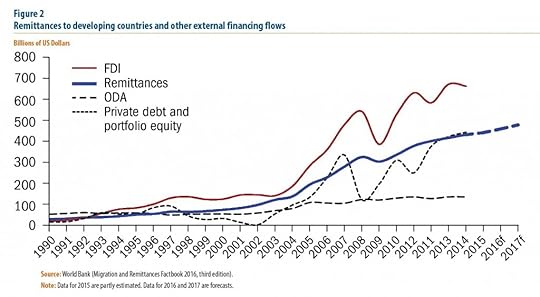

We should focus on ensuring development impact and mobilising resources. Aid still matters to low-income and conflict-ridden countries, but we need to constantly ask ourselves what works and how we can improve impact. To improve results, it is also more and more important that countries’ development policies stimulate and collaborate with other financial sources, such as private foundations’ investments, private capital and pension funds.

We should focus on ensuring development impact and mobilising resources. Aid still matters to low-income and conflict-ridden countries, but we need to constantly ask ourselves what works and how we can improve impact. To improve results, it is also more and more important that countries’ development policies stimulate and collaborate with other financial sources, such as private foundations’ investments, private capital and pension funds.

We should reach out to a broader range of development actors, beyond the DAC membership, to influence and be influenced, and to explore new development approaches. The eco-system of development stakeholders is changing with new donor countries, more private sector initiatives, NGOs and philanthropic organisations increasingly serving as sources of capital flows.

We should improve self-assessment and transparency. The core tasks of DAC are relevant and important, but we can improve our practices to increase access to information and hold each other to account.

Together with such necessary changes the DAC must keep delivering on its core functions. It has a unique role in upholding quality of development cooperation. The DAC must continue to define and measure development co-operation and through that be the guardian of the definition of Official Development Assistance (ODA). Setting standards for aid and facilitating members’ mutual accountability for development efforts will be no less important going forward. Peer learning and exchange of views is highly valued by the OECD members.

I have worked with the member countries since I took up this position last fall and to get the overall direction for this reform approved  by the committee at this week’s meeting was an important step. The committee will now present a more detailed action plan to the high-level meeting later this year, when member country ministers can endorse it. (To see the general direction and arguments for reform in more detail – download the High-level panel’s report.)

by the committee at this week’s meeting was an important step. The committee will now present a more detailed action plan to the high-level meeting later this year, when member country ministers can endorse it. (To see the general direction and arguments for reform in more detail – download the High-level panel’s report.)

Through a reformed DAC, members aim to contribute not only through development assistance but also through using its convening power to stimulate better practices among development stakeholders and facilitate new partnerships.

When we succeed the committee will have moved from a club to a hub, a hub not just for the rich countries that founded the OECD, but for all stakeholders involved in making development cooperation contribute to implementing the 2030 Agenda.

OECD is The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, an intergovernmental economic organisation with 35 member countries, founded in 1960 to stimulate economic progress and world trade.

DAC is the Development Assistance Committee of the OECD since 1961. It is a forum for many of the largest funders of aid, including 30 DAC Members. The World Bank, IMF and UNDP participate as observers.

ODA means Official Development Assistance and is flows of official financing to promote the economic development and welfare of low and middle income countries.

July 12, 2017

What has the iPhone got to do with inequality? New Oxfam Book Review blog

I often get asked for more book reviews on the blog (presumably to give readers the bluffer’s guide until they get round to reading the real thing, if  ever). So very happy to see that Oxfam’s research wonks have started ‘Book Banter’ – a development book review service. Follow here. Any other good sources of development book reviews? Here is Franziska Mager (right) on Mariana Mazzucato’s bestseller, T

he Entrepreneurial State

ever). So very happy to see that Oxfam’s research wonks have started ‘Book Banter’ – a development book review service. Follow here. Any other good sources of development book reviews? Here is Franziska Mager (right) on Mariana Mazzucato’s bestseller, T

he Entrepreneurial State

What is the role of the state in fostering innovation and economic growth? Mariana Mazzucato’s book, The Entrepreneurial State, reveals the role of the public sector in risk taking and the development of new technology, and argues that the state should receive more of the rewards. Research Assistant Franziska Mager reviews the book from an Oxfam perspective.

Why I read it

This book is perhaps a less obvious Oxfam read than a ‘classic’ guide to inequality like Deaton’s Great Escape. The foremost reason I picked it up was to learn more about the basics behind the alleged divide between the private and public sectors and why they may actually work together more than we think. Mazzucato mostly writes about technological and industrial innovations (iPhone, pharmaceuticals, wind turbines), which vividly illustrates particular ways in which the two sectors are played out against each other. I was hoping this book would inform the way I, as a non-expert, think about links between both spheres and perhaps better grasp how tax avoidance and inequality fit into the picture. I was not disappointed.

This book is perhaps a less obvious Oxfam read than a ‘classic’ guide to inequality like Deaton’s Great Escape. The foremost reason I picked it up was to learn more about the basics behind the alleged divide between the private and public sectors and why they may actually work together more than we think. Mazzucato mostly writes about technological and industrial innovations (iPhone, pharmaceuticals, wind turbines), which vividly illustrates particular ways in which the two sectors are played out against each other. I was hoping this book would inform the way I, as a non-expert, think about links between both spheres and perhaps better grasp how tax avoidance and inequality fit into the picture. I was not disappointed.

Why you should read it

To challenge black and white thinking

I’ve learnt that the links between the private and public sectors are much closer and more complex than both ‘sides’ want to admit – and most people seem to have a side. For me, this meant fundamentally challenging the way I think about how the public sector functions – which is important in my day to day job.

To better understand financialization and extreme wealth

Given how concerned Oxfam is with the wealthiest 1% of people and their disproportionate influence, we have spent relatively little time understanding this group in depth. The book lays out how private sector ventures or individuals – in particular, shareholders – have claimed a disproportionately big slice of the ‘risk pie’ on the returns from a product or service, meaning income and wealth gains are often more concentrated among those groups.

Key points to take away

Reframing risk

The state is often regarded as inherently scared, reluctant to take risks and invest in new things – credit for which usually goes to the private sector. But this is not always true, the book is full of interesting examples of highly risky public investments made without any guaranteed returns. The iPhone is a catchy example – the American public sector made a range of investments into research and development of different technologies that enabled visionary individuals at the right place and the right time to develop the iPhone. For the reader, and especially from an international development perspective, this triggers lots of questions. Is this a dynamic that we can learn from, that takes place in other policy areas? How much is the public sector consciously ‘snubbed’ when it comes to recognizing outputs?

Language really, really matters

The fact that the public and private sector work together much more closely than commonly acknowledged is both a cause and a consequence of using language in a mutually antagonizing way. The state in particular ‘has not had a good marketing/communications department’. This in turn contributes to a self-fulfilling prophecy. Less and less, the state is recognized as a dynamic actor interacting with the private sector in a complex risk landscape. Rather, if at all, it is acknowledged as the bad cop correcting market failures. In fact, our overblown linguistic focus on correcting by definition denies the state a leading role. The reality is more complex than that in areas way beyond industrial innovation.

Privatized rewards and link to inequality

Mazzucato does not argue against the principle that the Steve Jobs’ of this world should earn substantive wealth as a result of their  efforts and vision. Rather, she argues that there are many other ‘radical and path-breaking’ risks beyond venture capital and entrepreneurial visionaries that the state is involved in for which it is not getting a big enough slice of the risk rewards pie. This happens through different mechanisms – intellectual property rights, talent retention, tax evasion, time lags, legal contracts, to name just a few. This tendency towards socialized risks but privatized rewards means there is a link between industrial and innovation policy to growth and to inequality. The private sector generally manages to extract more value, partly thanks to shareholder culture. Mazzucato argues the public sector has a right to part of these rewards– rewards that it could and should reinvest in sustainable policy solutions and public services.

efforts and vision. Rather, she argues that there are many other ‘radical and path-breaking’ risks beyond venture capital and entrepreneurial visionaries that the state is involved in for which it is not getting a big enough slice of the risk rewards pie. This happens through different mechanisms – intellectual property rights, talent retention, tax evasion, time lags, legal contracts, to name just a few. This tendency towards socialized risks but privatized rewards means there is a link between industrial and innovation policy to growth and to inequality. The private sector generally manages to extract more value, partly thanks to shareholder culture. Mazzucato argues the public sector has a right to part of these rewards– rewards that it could and should reinvest in sustainable policy solutions and public services.

I wish there was more about…

Rewards and taxation: For me the last section of the book was of most interest. In particular, I was fascinated by the short description of how the taxation system interacts and compares with returns from state investments, and how much more the public sector could collect through closing the tax gap (tax income not collected), returns on public investments, or both. I would have liked more detail on this. At Oxfam we assume that calling attention to tax avoidance is one of the most effective and important ways to raise missing billions that can then be spent on essential services, but this is an important reminder that there are in fact lots of counterfactuals.

More diverse examples: I found myself caught out by the statement that ‘investments into programme areas that increase productivity have been less fashionable than simple spending on welfare state institutions such as education or health’. This book does a great job of explaining how some of the productivity that in fact powers an economy comes about. Essentially, I understand the points the book makes, but I craved even more practical examples to cement my thinking and from other areas than tech, Pharma and energy. It’s by no means a flaw – I just wish it was longer.

July 11, 2017

Which aspects of How Change Happens resonate with campaigners?

Writing, and then promoting, How Change Happens has often left me feeling a bit remote from ‘the field’, with a nagging anxiety that

What do we want? A theory of Change?…..

what I am saying no longer has much connection with what people are doing on (or at least closer to) the ground.

So it was great to get online with some of Oxfam’s best and brightest campaigners and advocates around the world and swap notes on power and systems. I got a reassuring amount of resonance with the ideas and arguments in the book, along with some really interesting experiences and new insights.

One overarching point is how much people value mapping tools – they provide entry points into disentangling a complex system, examining the different parts and how they interact, and then using that to come up with better ideas for ways to change the status quo. Oxfam staff are out there using tools like the Power Cube with local communities, and they really help. ‘Although people think a lot about power, mapping gives them new language and new ideas on what to do. They look again at things they previously took for granted.’ In contrast, Oxfamers are not so keen on big analytical documents – ‘pages of pages of nothingness’, was one memorable description.

power cube exploded

I discovered that my colleague Richard English has flattened out the Power Cube into a set of 3 columns, which works much better for me – I’ve never found the cube itself very user friendly. We decided to try and apply it to the problem of how to prevent governments from cracking down on civil society organizations. If that goes ahead, I’ll doubtless blog on the results.

When analysing power, one intriguing critique was that the aid business tends to favour structural analyses, and avoid analysing the experiences, motivations and preferences of powerful individuals. In advocacy that means we miss lots of entry points through which to influence decision makers – one recalled a long analysis of South Sudan that failed to mention that the main rebel leader, Riek Machar is a British citizen (and even studied Philosophy at Bradford University). That kind if intel can provide great entry points for influencing.

Another example of the need to take power analysis down to the individual level came from Cambodia, where we used power mapping to identify the individual decision makers and then who influenced them (i.e. who they listened to) as the basis for an influencing and campaign strategy.

Oxfam likes to use power mapping – typically plotting different stakeholders against the level of interest in/support for the issue

power map of climate change negotiations

under discussion and their degree of influence over relevant decisions. One African colleague saw one of the main benefits as uncovering those institutions that in practice have absolutely no power over decisions (whatever it says in the constitution), which can save a lot of time and waste (‘ultimately, Parliament is just a rubber stamp’).

But despite the enthusiasm for power mapping, I realized as we were talking that it has one serious flaw: it struggles to address ‘hidden power’ (social norms, the attitudes and beliefs that inspire or hold people back), and usually defaults back to the comfort zone of formal power, often extending to ‘hidden power’ – Old Boys’ Networks and the like. When many change processes (eg on gender rights) rely to a large extent on tackling social norms and ‘power within’, that seems like a serious oversight.

But in some countries, all this talk of power is itself a risk – technical, apolitical language can provide a kind of camouflage, when overtly political language attracts unwanted attention from the authorities. Not sure I’ve helped much there by writing a whole book on power and change. Too late now.

The people on the call were part of Oxfam’s Campaigns and Advocacy Leadership Programme (CALP). The CALP brings together Oxfam staff and partners involved in country programmes and the influencing done at local, national, regional and global levels. We have some exciting plans to make that more widely available, perhaps through a partnership with Open University. Watch this space.

July 10, 2017

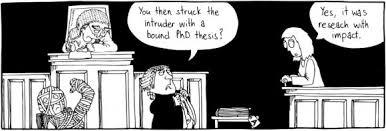

Are Academics really that bad at achieving/measuring Impact? Summary of last week’s punch-up

Last week’s post about academics struggling to design their research for impact certainly got a reaction. Maybe not a twitter storm, but  at least a bit of a squall. So it’s time to summarize the debate and reflect a bit.

at least a bit of a squall. So it’s time to summarize the debate and reflect a bit.

The post annoyed some people in the ‘research for impact’ community, because it was basically saying nothing much has changed. ‘The world has moved on’ said Pauline Rose of Cambridge University, ‘It is no longer academics versus NGOs/practitioners but very much working together, identifying commonalities and comparative advantages, and collectively wanting to ensure rigorous research that will achieve change; and in doing so, recognising the nuances of what impact is and how it can be achieved – including the need to start before the research even begins’. IDS’ James Georgalakis was more pithy: ‘Time to change the record’. Both reminded us that there is a lot going on and (‘fessing up here) I’m not across a lot of it. For example, the Rethinking Research Partnerships network and the Impact Initiative (for whom I’ve even written a piece on academic-NGO collaboration).

But their protestations reminded me of a recent conversation with an Oxfam evaluation guru who says one of the problems she faces is that in the aid business, 90% of the attention and conversation surrounds 10% of the work, often the best, most innovative bits. The other 90% is much more same old, same old. The trouble is that those of us looking at and/or contributing to the 10% conclude, like Pauline, that everything has moved on, when a lot of it hasn’t. It was the shock of being exposed to some bog standard stuff that led to the post – a small, doubtless unrepresentative sample, but perhaps more representative than the view from inside the 10% bubble. For the record, I get the same sense of frustration as James and Pauline when I hear people slagging off NGOs for being unreconstructed fools, knaves or often both, and it’s probably at least partly for similar 90/10 reasons (although it may just be that the work is rubbish).

Several commenters sounded warning bells about language. According to ODI’s Josephine Tsui ‘Whether you use the term advocacy, influence, or engagement, different groups will have an adverse reaction depending on their political situation. However the political process is the same, you have something to say and you need to target who you’re talking to.’

Several commenters sounded warning bells about language. According to ODI’s Josephine Tsui ‘Whether you use the term advocacy, influence, or engagement, different groups will have an adverse reaction depending on their political situation. However the political process is the same, you have something to say and you need to target who you’re talking to.’

So much for the blog. The twitter traffic was both more pro (lots of people recognizing the depressing portrait painted in the post) and more deeply critical.

Chicago University’s Chris Blattman weighed in with perhaps the deepest critique. In a series of tweets, he said:

‘This is the wrong way to think about research impact. It’s hardly this direct. The best research changes the intellectual conversation. It changes how textbooks are written. It changes what young scholars do next. It changes how undergraduates and MAs learn the discipline. The UK Government obsession with measuring policy impact of research will only help their universities fall behind. Academics will manage what is measured and turn into think tanks rather than make long term investments and take risks. Sad!’

Which reminded me of a painfully brief meeting with DFID’s head of research some years ago: ‘I’ve come to talk about Research for Advocacy’ I declared. ‘That’s an oxymoron’ he replied, ‘you either have research, or you have advocacy, but you can’t do both without contaminating the research’. Someone obviously forgot to tell the REF.

So, should academics deliberately seek to influence policy and beliefs, and try and ‘count what counts’, including the hard to measure stuff, or push back against the whole effort to oblige them to both achieve and measure impact? Just to prove that I haven’t been entirely seduced by academic preferences for nuance and shades of grey, it’s time for a poll

Note: There is a poll embedded within this post, please visit the site to participate in this post's poll.

But in the interests of nuance (ahem…), you can vote for more than one

July 9, 2017

Links I Liked

I’m in South Africa next week (19th-25th). Cape Town, then a couple of days in Joburg.

I’m in South Africa next week (19th-25th). Cape Town, then a couple of days in Joburg.  Only public event so far is on Friday 21st in Cape Town. Get in touch if you want to organize anything or simply meet up

Only public event so far is on Friday 21st in Cape Town. Get in touch if you want to organize anything or simply meet up

Oxfam stuff:

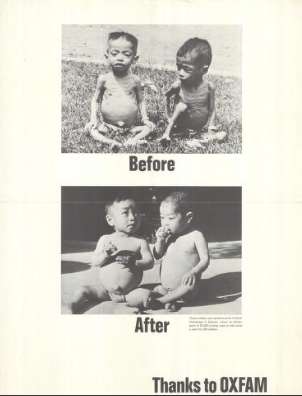

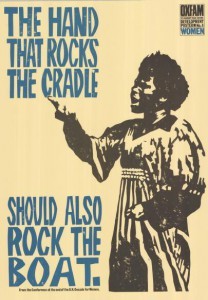

700 posters from the archive. Gold for students of charity history/changing use of images (both good and bad).

Heads up, bookworms. Oxfam research team now doing ‘book banter’ occasional reviews. First up Angus Deaton, Morten Jerven

‘Practical Action Bangladesh has written and produced a drama for national TV on Faecal Sludge Management‘. Shit reviews guaranteed

The UK’s PPP health financing disaster. Now being exported to a country near you.

Big loss to humanitarian journalism. Humanosphere shuts (maybe temporarily, maybe not) due to cash crunch. Any funders out there able to step up?

Harrowing, insightful piece by DFID’s Pete Vowles on a day’s immersion with a Kenyan family sunk deep below poverty line

Harrowing, insightful piece by DFID’s Pete Vowles on a day’s immersion with a Kenyan family sunk deep below poverty line

What unites psychopaths, economists and buddhist monks? Their answers to the trolley problem. h/t Chris Blattman

Why short term charitable giving might be making a comeback compared to long term philanthropy

Welcome to Rio on Thames. Extreme income inequality in Kensington & Chelsea, where the Grenfell Tower fire took place. UK’s richest/poorest deciles both present. h/t the Economist

July 5, 2017

What’s the problem with Globalization?

Globalization, remember that? When I first entered the development NGO scene in the late 90s it was all the rage. Lots of rage. The

Ah, those were the days

anti-globalization movement roared from summit to summit. Academics traded books and papers that boosted or critiqued. The World Bank used voodoo modelling to show that really we’d all be better off if we just got rid of borders altogether. As the Doha Round got under way in 2001, the WTO became the epicentre of protest. Even as a besuited insider ‘NGO delegate’, I sniffed the tear gas in Seattle (v exciting) and spent far too much time memorizing the articles of the Agreement on Agriculture (less so).

Since then, we’ve had 9/11, paralysis at the WTO, and the 2008-? Global Financial Crisis. No-one talks much about globalization these days, so an invitation from some research pals for a Chatham House Rules brainstorm on revisiting the issue piqued my interest. Some thoughts and questions emerging from the conversation.

Do we even know what the problem is? The initial discussions were very much between economists (liberalization v industrial policy; one size fits all v national specificity). But the backlash against globalization has pulled in many other ways of looking at the world – anthropology and cultural studies on immigration and ‘othering’ of outsiders; politics on the rise of populism; sociology on the nature and impact of inequalities; environmentalists on planetary boundaries and GDP. Might be worthwhile asking globalization-watchers from 10 different academic disciplines to discuss the problem, and see what they come up with.

Is this a Western issue? Even smart people in the US and Europe find it hard to stop domestic politics colouring how they interpret the world. As a Latin Americanist, I find it odd the way ‘we’ have just discovered populism – in many ways Donald Trump reminds me of a traditional Latin American caudillo (if Peron had had twitter….). So obviously, we need to ask around – how does globalization look from Beijing or Bamako?

Is this a Western issue? Even smart people in the US and Europe find it hard to stop domestic politics colouring how they interpret the world. As a Latin Americanist, I find it odd the way ‘we’ have just discovered populism – in many ways Donald Trump reminds me of a traditional Latin American caudillo (if Peron had had twitter….). So obviously, we need to ask around – how does globalization look from Beijing or Bamako?

What can we learn from history? Learning from history is difficult, not least because it is a combination of unidirectional change (new technologies, falling transport costs, rising literacy, urbanization) and cyclical change (the state v market pendulum, inclusivity v ‘othering’ the outsider). So it doesn’t really repeat itself. Nevetheless, we’ve seen big reversals and paradigm shifts before – peak globalization at the end of the 19th Century disintegrated into war and protectionism; the long Keynesian boom post World War 2 gave way to the harsher world of Friedman and neoliberalism. The traumas of 2008 and its aftermath don’t seem to be leading to a similar paradigm shift – or is it just too early to say?

Politics v Institutions: Politicians are more instinctive, and have the feedback loops in place so that they are rewarded if they capture the zeitgeist. Hence the rise of populism. Institutions seem altogether more sclerotic – they maintain paradigms rather than challenge them. Hardly surprising then that we are seeing a growing distance and tension between the two. Institutions typically try and constrain mould-breakers, bring them back to the existing paradigm, which is often a very good idea, but how would institutions need to change to adapt to the emerging problems of and changed political discourse on globalization?

This is not about post-globalization: We are not in a Newton v Einstein paradigm shift here. Because of the unidirectional elements of change, some aspects of globalization are likely to endure – so maybe those critical of the current manifestations of globalization should identify the best candidates for potential positive outcomes and focus on them until the dust settles, rather than keep pushing against the tide in search of that elusive new paradigm. Migration for example, why not focus on exploring how to make remittances work better for humanitarian response; social investment; conflict resolution?

Linear v Systems: In retrospect, the early 00s debates were based on a big assumption – that someone was in charge. Change policy at the WTO and boom – problem solved. One of the striking features of the last 20 years is the growing complexity of the institutions and patterns of globalization – multiple, overlapping institutions, regional powers etc etc. What would a shift to systems thinking, along the lines of Andy Haldane on complexity and the financial sector, bring to the party? One consequence might be a shift from IIRTW (If I Ruled the World) to positive deviance – identify those sectors, institutions etc that have survived and flourished through the upheavals of the last 50 years, because they are likely to be constituent elements of whatever emerges from the current mess.

at the WTO and boom – problem solved. One of the striking features of the last 20 years is the growing complexity of the institutions and patterns of globalization – multiple, overlapping institutions, regional powers etc etc. What would a shift to systems thinking, along the lines of Andy Haldane on complexity and the financial sector, bring to the party? One consequence might be a shift from IIRTW (If I Ruled the World) to positive deviance – identify those sectors, institutions etc that have survived and flourished through the upheavals of the last 50 years, because they are likely to be constituent elements of whatever emerges from the current mess.

All a bit meta, I know, but it was that kind of conversation. Thoughts?

$15bn is spent every year on training, with disappointing results. Why the aid industry needs to rethink ‘capacity building’.

Guest post from Lisa Denney of ODI

Every year a quarter of international aid – approximately US$15 billion globally – is spent on capacity development. That is, on sending technical assistants to work in ministries or civil society, running training programmes, conducting study tours or exchanges, or supplying resources and equipment to help organisations function better. This is often referred to as ‘teaching men to fish.’ Rather than giving men (or, one might add, women) fish, teaching men to fish is seen to provide sustainable capabilities that will empower people and eventually negate the need for external support. Yet this task, far from being the technical transfer of skills, is fundamentally about social and political change.

In countries affected by conflict or fragility, this assistance is not just about improving development outcomes but is also expected to strengthen the state itself – because its very weakness is framed as both a cause and consequence of violence and underdevelopment. By defining state fragility as a problem of weak capacity, capacity development becomes the primary solution. It is also, conveniently, a problem that donors and NGOs can do something about – by providing capacity development programs.

But despite the dominance of this idea, results in practice are frequently disappointing. This is borne out by six-years of research by the Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium (SLRC) on state capacity and how it tends to get built in eight countries (Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nepal, Pakistan, Sierra Leone, Sri Lanka, South Sudan and Uganda). While diverse, the studies point to a range of familiar challenges, including:

But despite the dominance of this idea, results in practice are frequently disappointing. This is borne out by six-years of research by the Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium (SLRC) on state capacity and how it tends to get built in eight countries (Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nepal, Pakistan, Sierra Leone, Sri Lanka, South Sudan and Uganda). While diverse, the studies point to a range of familiar challenges, including:

the limited toolkit of capacity development approaches (as one respondent in Sierra Leone noted ‘training, training, training – how much training does one person need?’);

the focus on technical aspects of service delivery, neglecting how power and politics are at the root of many problems that appear to be about capacity;

the neglect of alternative capacities outside of the formal realm or what Western notions of ‘capacity’ look like; and

a focus on tangible ‘units’ of a delivery systems (that is, individuals and organisations) and less on the system as a whole and how its parts interact.

Given that capacity development activities stretch back to at least the 1950s, why the frequent lament of poor results? (The SLRC synthesis report is far from the first study to point to these limitations).

The SLRC research finds many of the reasons are to do with the political economy of the aid industry itself – short timeframes, quantitatively-driven results reporting, risk aversion and an emphasis on technical rather than political and contextual skills and knowledge. But perhaps most fundamentally, and what all these factors derive from, is the fact that the aid industry turns fundamentally political processes of social and institutional change into projects – which are in turn cloaked in value-neutral technocracy. The problems become ones of limited equipment or resources, insufficient knowledge, weak coordination, poor monitoring, and so on, rather than about power, incentives and interests.

So, we see aid programmes attempting to improve service delivery in Afghanistan by building the technical capacity of village development councils, overlooking the incentives of local power brokers who hold the real sway in how services are delivered. Or programmes imply that malnutrition in Sierra Leone can be reduced by training mothers in infant and young child feeding, with little regard for the gendered power relations that mean women have little control over household finances and serve the most nutritious meal portions to older men. In South Sudan, there are examples of statebuilding being boiled down to workshops – often conducted in English – to address complex social transformations, such as local justice and peacebuilding. In all of these cases, the complexity, power and politics of the changes sought are sidestepped and turned into technical, more easily-delivered projects.

development councils, overlooking the incentives of local power brokers who hold the real sway in how services are delivered. Or programmes imply that malnutrition in Sierra Leone can be reduced by training mothers in infant and young child feeding, with little regard for the gendered power relations that mean women have little control over household finances and serve the most nutritious meal portions to older men. In South Sudan, there are examples of statebuilding being boiled down to workshops – often conducted in English – to address complex social transformations, such as local justice and peacebuilding. In all of these cases, the complexity, power and politics of the changes sought are sidestepped and turned into technical, more easily-delivered projects.

We would never think to use logframes and value for money calculations to manage the civil rights movement, for instance (although such programme management tools are used for all kinds of domestic social policy reforms). So why do we think that processes of social change can be projectized in countries affected by conflict or fragility? Is it because, while we recognise the politics inherent in some social change in our own countries, we strip it out from social change processes elsewhere and treat problems as ones of capacity alone?

To address these limitations, the SLRC argues that we need a re-politicisation of capacity development, acknowledging that we are ultimately interested in fostering social and political change. That might be by making service delivery more equitable, changing power relations in the household, or making governance arrangements more accountable. None of these are technical endeavours. Rather than shying away from this politics, we must put it front and centre and engage with it.

To do so, we might start from building a nuanced understanding of how people use services in practice – recognising what drives people’s decision-making and the breadth of providers people rely on, often extending beyond the state. We must move beyond thinking about capacity as the tangible assets of individuals (eg: teachers) and organisations (eg: schools) and begin to think much more holistically about the capacity of systems. Ensuring health workers have good technical knowledge does not make a well-functioning health system on its own. Ensuring that staff also have good bedside manner, the trust of the community, access to reliable drug supply chains, are paid on time and so do not charge bribes or sell drugs on the black market, and so on also matter.

To do so, we might start from building a nuanced understanding of how people use services in practice – recognising what drives people’s decision-making and the breadth of providers people rely on, often extending beyond the state. We must move beyond thinking about capacity as the tangible assets of individuals (eg: teachers) and organisations (eg: schools) and begin to think much more holistically about the capacity of systems. Ensuring health workers have good technical knowledge does not make a well-functioning health system on its own. Ensuring that staff also have good bedside manner, the trust of the community, access to reliable drug supply chains, are paid on time and so do not charge bribes or sell drugs on the black market, and so on also matter.

Finally, we must be prepared to change our ways of working and thinking about the challenges faced in countries affected by conflict and fragility and move beyond the idea that capacity is the key constraint and therefore capacity development the natural answer. Rather, we need to bring to bear a much wider toolkit to support what are social and political processes of change. Ironically, this may begin by improving the capacity of development practitioners themselves to support such change processes.

July 4, 2017

Two days with the Radiographers of Power

Spent another couple of days with the International Budget Partnership (IBP) last week. If budgets sound boring and bean-counter  ish, consider this quote from Rudolf Goldscheid: “the budget is the skeleton of the state stripped of all misleading ideologies.” Follow the money, because the rest is spin. The IBP trains and supports civil society organizations (CSOs) in dozens of countries to become better radiographers of that skeleton (and takes the odd X ray itself).

ish, consider this quote from Rudolf Goldscheid: “the budget is the skeleton of the state stripped of all misleading ideologies.” Follow the money, because the rest is spin. The IBP trains and supports civil society organizations (CSOs) in dozens of countries to become better radiographers of that skeleton (and takes the odd X ray itself).

The conversation was intense. IBP reminds me of Twaweza in its readiness to be open about weakness and failure, and its thirst for new ideas to improve its work. Some of the topics that surfaced:

Where is the budget transparency movement, 20 years on?

Much more info is now available, but is not always being used, or in a useful form. That gives a perfect excuse to recalcitrant governments – ‘why should we release more data when no-one used the last lot?!’.

There is isomorphic mimicry on all sides. 100+ countries have transparency rules, but few have led to lasting changes of behaviour. There is plenty of ‘Openwash’ from governments, who move the important stuff off budget and out of sight, eg via state owned enterprises. On the civil society side, more groups are chasing grants by claiming to be ‘doing transparency’, but there is ‘a lot of fakeness’ – ‘groups coming to us saying ‘we have got the funding from a donor to do this budget project, and we have to report next week, can you help us?’’ A case for some kind of certification scheme?

The low hanging fruit have been harvested. Now (e.g. in Indonesia and Latin America) budget advocacy is hitting the walls of vested interests – eg mining codes, tax, pension reform. Data alone is not enough (see below).

Very few CSOs are yet moving beyond spending to look at tax. Although IBP is working with Latin American CSOs on this, the vast majority of work on tax remains international – e.g. tax havens and illicit flows.

Data in a Downturn

North and South, IBP staff see alarming changes in the climate for their work. Growing distrust of ‘experts’ and institutions, and a post-truth, or at least post-data environment are an existential threat for an organization with a deeply rationalist theory of action based on ‘get the data out there, and people will use it to influence governments’. In some cases, new forms of activism are emerging, but they tend to be more ephemeral, atomized, uninstitutionalised (or in some cases anti-institutional).

In such circumstances do you stick with data and evidence, working with the people, eg progressive civil servants, who still care about them (even if such allies seem to be shrinking in number)? Or do you move towards a more narrative-based form of advocacy, with more emphasis on stories, myths and emotions?

In such circumstances do you stick with data and evidence, working with the people, eg progressive civil servants, who still care about them (even if such allies seem to be shrinking in number)? Or do you move towards a more narrative-based form of advocacy, with more emphasis on stories, myths and emotions?

Do you get more adversarial, in response to all this? Tricky because ‘Our strongest weapon is asking nicely, and identifying the sorts of people likely to respond to being asked nicely. Where the state says ‘no’, it is much harder to know what to do – we are far stronger on an inside game.’

Possible Ways Forward

So what might an IBP theory of action for these new conditions look like? There are several months of this discussion left, but ideas that emerged last week included:

Continuity and Change: Staff get impatient, worry about the perceived lack of real world impact, are lured by the excitement of working closer to the grassroots, but for a small international NGO like IBP, continuity has a lot going for it. Its cautious, superficially apolitical tone, focussed on data and transparency, give it precious traction with economic liberals and political conservatives at a time of political downturn. Through its influential Open Budgets Survey and international advocacy, it has played a central role in what has become a much broader transparency and accountability movement. Frustration with the slow pace of change and the understandable desire to move beyond mere data, and get more transformational may reflect the new situation (or the exhaustion of the current model/end of the low hanging fruit), but be careful on what you sacrifice in the process – throwing out babies, bathwater etc.

Global v National: although national and local work are often a lot more exciting than traipsing round the international conference circuit, IBP has played a crucial role in getting budget transparency onto the international agenda. As space closes at national level, it should definitely keep going in consolidating the global commitments.

Fragile States: the aid business is heading into fragile and conflict settings, partly because that’s where most of the poor people will be in 20 years’ time. I came away with the strong feeling that IBP should steer well clear. With absent or predatory governments, and a weak and under siege civil society, the chances of winning a few in messy places seem vanishingly small.

be in 20 years’ time. I came away with the strong feeling that IBP should steer well clear. With absent or predatory governments, and a weak and under siege civil society, the chances of winning a few in messy places seem vanishingly small.

Civil Society is Bigger than Civil Society Organizations: like most INGOs, IBP has slid into conflating civil society with formal CSOs, at least in terms of its core partners. But many other actors care about transparency and accountability, and may be ready to act even in the absence of the strong CSOs on which IBP’s work is currently predicated. This may well be the moment to consciously broaden the movement to deepen links with the private sector, academia, the media, faith organizations etc etc.

Technology really matters: I’m generally a tech sceptic (over-hyped quick fix solutions that conveniently ignore power and politics). Not on this one though. The technological possibilities are advancing rapidly – IBP needs to move on from periodic big picture reports to provide realtime, easily customized, online data. Imagine the usefulness to grassroots activists of an app that allows them to immediately download their village/city budget and compare it with actual spending. But the power and politics will still matter – one IBP staffer warned us to beware the ‘Millennial tech quick fixers with short attention spans. Their organization has 10 people with 45 projects. They think you put on your headphones, do some coding and its done.’ Love it.

But above all, stick with budgets – whatever further weirdness affects politics over the next few years, one thing is certain: budgets will remain the skeleton of the state, and X ray specialists will be essential to tell us who they are hurting or helping.

July 3, 2017

If academics are serious about research impact, they need to learn from advocates

As someone who works for both Oxfam and the LSE, I often get roped in to discuss how research can have more  impact on ‘practitioners’ and policy. This is a big deal in academia – the UK government runs a periodic ‘research excellence framework’ (REF) exercise, which allocates funds for university research on the basis both of their academic quality and their impact. Impact accounted for 20% in the last REF, which reported in 2014, and I’m told could get an even greater weighting in the next one, in 2021. That means hundreds of millions of quid are at stake, so universities are trying to get better at achieving and measuring impact (or at least looking like they are!) as they start to prepare for the next round of submissions.

impact on ‘practitioners’ and policy. This is a big deal in academia – the UK government runs a periodic ‘research excellence framework’ (REF) exercise, which allocates funds for university research on the basis both of their academic quality and their impact. Impact accounted for 20% in the last REF, which reported in 2014, and I’m told could get an even greater weighting in the next one, in 2021. That means hundreds of millions of quid are at stake, so universities are trying to get better at achieving and measuring impact (or at least looking like they are!) as they start to prepare for the next round of submissions.

And they have a way to go, based on my recent experience of listening to pitches from a range of researchers. Some interesting patterns emerged, both in terms of weaknesses and ways to address them.

First up, many academics fall into the classic mistake of equating frenetic activity with impact. Long lists of meetings attended, papers published, speeches given etc do not impact make. I think they should start from a different place – how would you set about convincing an intelligent, fair minded sceptic of the impact of your research?

That might be a challenge because the way a lot of researchers think about their impact seems pretty rudimentary. Finish the research, publish the papers, run a few seminars, produce a policy brief and (at the less stuffy end) bash out some social media and voila! Unfortunately, ‘blog it and they will come’ is often not a very convincing influencing strategy.

That might be a challenge because the way a lot of researchers think about their impact seems pretty rudimentary. Finish the research, publish the papers, run a few seminars, produce a policy brief and (at the less stuffy end) bash out some social media and voila! Unfortunately, ‘blog it and they will come’ is often not a very convincing influencing strategy.

A popular alternative in REF submissions is the adviser/consultancy model – ‘the UN/Government asked me to present/be on a panel/draft their guidelines – now that’s impact’. A bit more convincing, but both approaches would benefit from a more explicit theory of change, running through some of the following issues:

Stakeholder and Power mapping

For the change you are advocating, who are the likely champions, drivers and undecided who you can seek to win over

Who has the power over the decisions you are trying to influence? They are probably going to be your main targets.

Who/what in turn influences those targets? Is it evidence (if so, what kind?), or something else entirely, like the identity of the messenger?

How do you get targets to be aware of and interested in your research in the first place (since both decision makers and practitioners live in the land of TL;DR)? Have you tried to involve them in it, for example by asking them to be on a reference group, comment on drafts or be interviewed for it? Much better than just adding your paper to their reading pile.

Dynamics:

Is the change you seek likely to be smooth or spikey – some changes are largely crisis driven, in which case your  influencing strategy will have to try to get ready in advance, identify and make the most of crises or other ‘windows of opportunity’. As Pasteur said, ‘fortune favours the prepared mind’. This is antithetical to the normal rhythm of research – a steady, high pressure grind of papers and presentations, largely oblivious to events out there in the world.

influencing strategy will have to try to get ready in advance, identify and make the most of crises or other ‘windows of opportunity’. As Pasteur said, ‘fortune favours the prepared mind’. This is antithetical to the normal rhythm of research – a steady, high pressure grind of papers and presentations, largely oblivious to events out there in the world.

Insider v Outsider strategy

Insiders prize being ‘in the room’, and see themselves as deeply engaged in policy formulation. Outsiders are more interested in constructing alliances, working with (and providing ammunition for) activists and civil society organizations, and talking to the media. But both need to think through their influencing strategies. On the insider route, are the people in this particular room really the people making the decisions? Which invitations do you say no to (if only to avoid death by consultation)? For outsiders, what are the alliances you need in order to reach and influence the decision makers on this particular issue? In both cases, what kind of research (both in content and presentation) is most likely to get people’s attention?

Attribution:

Both approaches struggle with attribution. According to one insider ‘the ministry is a black box – you’re invited to speak. They say a polite thankyou. That’s it.’ How do you know if you changed anything? The challenges with outsider strategies are different – in an alliance of a dozen CSOs, thinktanks and universities, even if something changes, how do you apportion credit?

The efforts at attribution are currently pretty crude: count the citations and if you think your research has helped someone, you beg them for an email saying just how brilliant you are and how much impact you have had. Better than nothing, but pretty dubious as a sole source of evidence (right up there with job references in terms of rigour….).

There’s a lot that academics could learn from the MEL (monitoring, evaluation and learning) teams in the aid agencies here – they have some incredibly smart people working on this. I’ve seen Oxfam’s Effective Reviews really invest in trying to measure impact by constructing a plausible control group for comparison, through propensity score matching, or comparing and ranking different causal factors through process tracing. The academics I’ve talked to seemed entirely unaware of these kinds of methods. Given the multi-million pound benefits of getting it right, there may be a case for universities to outsource (and pay for) this either to ‘impact partners’ such as NGOs with more experience in the area, or to third party specialist organizations that could accompany researchers in design for impact, and then measure the results more rigorously.

There’s a lot that academics could learn from the MEL (monitoring, evaluation and learning) teams in the aid agencies here – they have some incredibly smart people working on this. I’ve seen Oxfam’s Effective Reviews really invest in trying to measure impact by constructing a plausible control group for comparison, through propensity score matching, or comparing and ranking different causal factors through process tracing. The academics I’ve talked to seemed entirely unaware of these kinds of methods. Given the multi-million pound benefits of getting it right, there may be a case for universities to outsource (and pay for) this either to ‘impact partners’ such as NGOs with more experience in the area, or to third party specialist organizations that could accompany researchers in design for impact, and then measure the results more rigorously.

Then there’s comms. The default tone is neutral and cautious – goals were to ‘shift’ this or ‘support’ that without ever specifying why or towards what. That feels more like avoiding mistakes than communicating a message. One alternative would be to come up with a clear mission statement – ‘we use evidence to change public opinion so that X happens’. If that’s too close to a credibility-damaging move into overt campaigning, academics should at least be able to clearly identify their USP (unique selling point) – eg ‘I’m the only person in the UK who knows what is going on in these particular far-off places’, and clearly state what their research is about in such a way that normal people and REF panels can understand.

That sounds like an extended moan, but perhaps most striking in the conversations I’ve had is how much impact appears to be taking place anyway – I came away with the impression that a bit more analysis and explicit discussion of assumptions and influencing strategies could be an incredibly productive exercise for Universities seeking to turn research into real impact.

July 2, 2017

Links I Liked

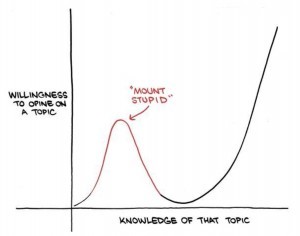

Mount Stupid, the perfect first slide for most of my presentations…..

RIP Michael Bond, creator of Paddington Bear, one of Britain’s best loved illegal migrants. Here’s a delightful 2014 analysis of his legal status

Man with 176 children seeks government support. ‘I receive 10 calls every day from different wives who want attention…’

How can education systems be better? Round-up of new research papers/videos from recent conference by David Evans

The father-son T shirt thing just escalated (click to expand). h/t @SMussani1 & @OGBEARD

The father-son T shirt thing just escalated (click to expand). h/t @SMussani1 & @OGBEARD

‘The dirtiest fights were with the tobacco industry’. Margaret Chan reflects on a decade leading the WHO

Theresa May and the Holy Grail. Sheer genius. Makes UK politics feel even odder than ever h/t Rachael Swindon

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers