Duncan Green's Blog, page 118

May 17, 2017

Why Faith-Based Organizations are particularly well suited to ‘Doing Development Differently’

Last week, I went in to talk How Change Happens with a bunch of CEOs and other senior staff from major Catholic aid agencies,

Much too linear…..

including CAFOD, the first development outfit foolish enough to give me a job back in the 90s.

We covered a lot of the standard ground – the results agenda, private sector approaches to innovation, the future (if any) of traditional northern/international NGOs, what Brexit and the US election mean for our future work. But what most struck me was the realization that faith-based aid organizations are in some ways ideally placed to take advantage of some of the new thinking in aid and development. For example:

Norms: If you buy the argument that activists in general (and development organizations in particular) need to pay more attention to how social norms are formed and shaped, it’s hard to think who is better placed than faith-based organizations. Through worship, education etc they already play a major role in shaping and reshaping norms, so it should be much easier for them than for more technocratic, secular aid agencies (like Oxfam), to move across from a focus on policies and behaviours to something deeper. I was also struck by the level of Catholic collaboration with Islamic agencies, such as Islamic Relief, which could provide an interesting option of working jointly on norms (eg attitudes towards refugees and migrants).

Fragile States: The future of aid may well lie in the fragile and conflict-affected states and sub-states that will increasingly be home to the world’s remaining very poor people. By definition, state mechanisms in those places are useless, absent or predatory. In such situations, the role of non-state actors such as faith organizations becomes relatively more important in running society, managing disputes etc. Plus faith organizations are more likely to be in the really remote bits of those places, where the state barely penetrates (I still remember coming across itinerant evangelical preachers miles from the nearest road while on patrol with the Sandinista army in Nicaragua during the middle of the 1980s civil war). If international faith-based organizations can hook up with those local faith networks then, like Heineken, they really can reach the parts other do gooders cannot reach.

Transition out of aid: I have been banging on for a while now about how northern and international NGOs should invest more in helping southern organizations develop domestic sources of funding. That will reduce their vulnerability to the fashions of the aid business, and increase their local linkages and accountability. Turns out that the Catholics, at least, are already on it. When CAFOD agreed to help Caritas Nigeria start raising more money from Nigerians, they were so overwhelmed by the response they had to scramble more management support to help Caritas cope with the flood of donations. Caritas Peru has also become a highly effective local fund raiser with local affinity cards and all the rest.

Transition out of aid: I have been banging on for a while now about how northern and international NGOs should invest more in helping southern organizations develop domestic sources of funding. That will reduce their vulnerability to the fashions of the aid business, and increase their local linkages and accountability. Turns out that the Catholics, at least, are already on it. When CAFOD agreed to help Caritas Nigeria start raising more money from Nigerians, they were so overwhelmed by the response they had to scramble more management support to help Caritas cope with the flood of donations. Caritas Peru has also become a highly effective local fund raiser with local affinity cards and all the rest.

Civil Society Space: I haven’t seen any research on it, but I’m pretty confident that secular CSOs are more vulnerable to closing civil society space than faith-based ones with large faith organizations behind them. Much harder to paint them as tools of foreign powers (except perhaps in countries with a Christian minority). So increasing support to faith organizations could be part of a response to the crackdown.

Of course I realize that faith-based organizations have their own problems (especially round all things to do with the body – being at CAFOD when it led the global Catholic response on HIV&AIDS was educational, to put it mildly), but I still think the overall balance could be positive and worth thinking about.

Views?

May 16, 2017

Why rethinking how we work on market systems and the private sector is really hard

Whatever your ideological biases about ‘the private sector’ (often weirdly conflated with transnational corporations in NGO-land), markets really matter to poor people (feeding families, earning a living, that kind of thing). But ‘making markets work for the poor’ turns out to be really difficult and, just as with attempts to tackle corruption or improve institutions, there is a rethink going on in the aid business. Critics of conventional approaches (of which I am one) argue that systems thinking and complexity both explain why a lot of previous approaches haven’t worked that well, and suggest some new ways to tackle the problem.

To catch up on some new research on all this, I spent a fascinating afternoon at DFID last week. The ‘knowledge hub’ BEAM Exchange (they don’t like to be called a thinktank)  presented a discussion paper and technical paper on ‘rethinking systemic change’, along with a warts-and-all case study from Palladium on the difficulty of trying to put this into practice in a large market development programme in Uganda. Some highlights.

presented a discussion paper and technical paper on ‘rethinking systemic change’, along with a warts-and-all case study from Palladium on the difficulty of trying to put this into practice in a large market development programme in Uganda. Some highlights.

The discussion and technical papers reviewed the lessons from the 3 elements of New Economic Thinking: evolutionary economics, new institutional economics and complex adaptive systems. Eric Beinhocker’s influence much in evidence. The papers draw some useful and pretty challenging conclusions:

‘The aim of development must be to enhance the evolutionary process in an economy and create access to this process for all levels of the society, both politically and economically.’

‘Institutional change cannot be put in place by solving problems and scaling them up. Institutional change can only occur if the local actors who are part of the system become aware of their role in the system and have options to purposefully influence institutional evolution. A group that is targeted by an intervention is likely to become more marginalised, not less – a boundary is drawn around the people, and the group is given an often highly simplistic and idiosyncratic label, such as ‘the poor’. Instead of labelling groups of people, the aim of market systems development should be to create opportunities for all people to engage in a functioning market economy.’

The authors, Shawn Cunningham and Marcus Jenal, find that a lot of people say they are thinking in systems, but they really aren’t:

The authors, Shawn Cunningham and Marcus Jenal, find that a lot of people say they are thinking in systems, but they really aren’t:

‘Too often in our work we see programmes claiming to work towards achieving systemic change while they are busy fixing narrowly defined problems guided by very specific objectives in very short time frames, while ignoring the broader systemic context. They then expect to be able to ‘scale-up’ the solution they have found and through that make it ‘systemic’.’ Ouch.

As is often the way, the critique is more powerful than the proposed solution – a set of 7 pretty generic and unobjectionable ‘general principles’ for those working on market systems (e.g. ‘create and maintain situational awareness’).

But what really made it real for me was the case study on Uganda. The paper, by Palladium’s Andrew Koleros, discusses the challenges faced during the inception phase of a £15m, 6 year programme: “Northern Uganda: Transforming the Economy through Climate Smart Agribusiness – Market Development (NUTEC-MD)”. It compares the project’s experience during its first year with the insights provided by the BEAM think pieces.

What came graphically across in the case study and seminar discussion is the tension between good intentions in design and the subsequent pressures to deliver short term, predictable results in tight timeframes. Systems thinking informed NUTEC’s initial analyses and approach. That initial desire to understand and ‘dance with’ the system however, was swiftly undermined by the pressures of running a multi-million pound project and in particular, the demand to both predict in advance, and then achieve, pre-agreed results. In practice this seems to have generated a lot of anxiety, pressure and an emphasis on ‘us’: what do we do? How do we hit the target of 75,000 families in 6 years? How do we find some quick wins to keep DFID happy? This is in conflict with and rapidly squeezes out efforts to walk the walk in terms of dancing with the system, bottom up solutions, engaging with positive deviance and understanding and supporting endogenous change processes.

This tension also led to a shift to safe bets – a 9 month inception phase was meant to produce proposals to reach a quarter of the 75k households. So the team ended up importing and adapting successful interventions from elsewhere in Uganda to ensure it met its donor targets, rather than trying to identify and support solutions emerging locally.

NUTEC’s inception phase ended a little over a year ago. Since then, the team says it has had more breathing space. It has been able to step back and take a more holistic, participatory approach to engagement with local market actors. But tensions remain.

Hats off both to Palladium for being candid about some of the problems it faced and to DFID, for creating the space for critical reflection.

Some wider thoughts from the ensuing discussion:

There is no guru: local business people often have fixed ideas about what is wrong, and they may not be the best ones. Outsiders have partial knowledge at  best. So surely a good approach is to find ways to programme in uncertainty – eg multiple parallel experiments (see my current favourite 2×2 – there seems to be a huge resistance from aid agencies to going below the x axis).

best. So surely a good approach is to find ways to programme in uncertainty – eg multiple parallel experiments (see my current favourite 2×2 – there seems to be a huge resistance from aid agencies to going below the x axis).

The relative power of outsiders and endogenous drivers of change seems to matter. It may be harder to ‘dance with the system’ when the aid business is a 300kg gorilla, and the system a relatively flimsy stripling, as in Uganda. Harvey Koh presented FSG’s Rockefeller-funded study of the Indian dairy cooperative, Amul – did that do better because of the size and self confidence (especially post independence) of Indian reformers, and the secondary role of outsiders? (I’ll blog on the Amul story when FSG finally publish its paper).

How could a portfolio approach help: as long as each project is under pressure to hit its individual targets, you get plain vanilla and safe bets. Can you take a portfolio approach within a project, e.g. by establishing a minimum acceptable target for results, and then having innovation on top? Could Payment by Results have a role? Or a portfolio approach across a region, country or donor, that looks for a blend of safe bets and high risk/high innovation projects?

Finally, it still feels like there is a real need for market systems people to catch up with the work on institutional reform by the governance people – Doing Development Differently, Building State Capability and so on. Governance people seem to have made a lot more headway in understanding what goes on in the black box of institutions, and how to influence it. Some of those insights might well be relevant to market institutions too.

And we really need some more iconic positive market systems stories, like SAVI on governance – hurry up on Amul, please!

May 15, 2017

Is Climate Change to blame for the East African Drought?

An honest attempt to engage with the evidence may seem almost quaint in these angry, post-truth times, but I was impressed by a recent Oxfam media

A young girl stands amid the freshly made graves of 70 children many of whom died of malnutrition. Dadaab refugee camp.

briefing by Tracy Carty on the thorny topic of whether climate change is to blame for the current East African drought. It’s an excellent example of the balancing act advocacy organizations have to perform on attribution: start making sweeping statements about climate change being the cause and you lose credibility, but sit on your hands for fear of being caught out and you risk missing a chance to get the urgent message on climate change out to new audiences.

Here’s where the briefing comes down:

The situation: ‘Nearly thirteen million people in Kenya, Ethiopia and Somalia are dangerously hungry and in need of humanitarian assistance. The worst drought-affected areas in Somalia are on the brink of famine. The crisis could deteriorate significantly over the coming weeks, as rainfall in March and early April was very low in places and poor rainfall is forecast for April through June, which is the end of the rainy season.’

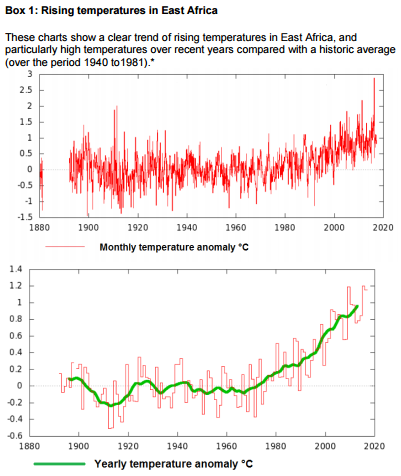

The link to climate change: ‘There is mounting evidence that climate change is likely to be contributing to higher temperatures in the region, and that increased temperatures are exacerbating the impacts of drought. Temperatures have been consistently higher in East Africa in recent years, part of a trend seen in Africa and around the world (see fig). Higher temperatures result in greater evaporation, meaning soil moisture is reduced, reinforcing drier conditions and intensifying the impacts of failed rains. Crops and pasture have less water, and the chance of failed harvests or lack of feed for livestock increases. In pastoral regions like northern Somalia, higher temperatures over the past six months have turned very low rainfall last year into a terrible loss of soil moisture – helping to desiccate all the available fodder for many of Somalia’s pastoralists.’

The link to climate change: ‘There is mounting evidence that climate change is likely to be contributing to higher temperatures in the region, and that increased temperatures are exacerbating the impacts of drought. Temperatures have been consistently higher in East Africa in recent years, part of a trend seen in Africa and around the world (see fig). Higher temperatures result in greater evaporation, meaning soil moisture is reduced, reinforcing drier conditions and intensifying the impacts of failed rains. Crops and pasture have less water, and the chance of failed harvests or lack of feed for livestock increases. In pastoral regions like northern Somalia, higher temperatures over the past six months have turned very low rainfall last year into a terrible loss of soil moisture – helping to desiccate all the available fodder for many of Somalia’s pastoralists.’

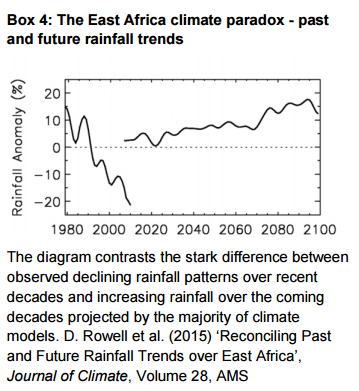

But the link between climate change and higher temperatures is much stronger than the link to lower rainfall, which is very unclear:

‘Temperatures are set to rise, but there is uncertainty on what long-term precipitation trends will be for the region. Most climate models, as set out in the IPCC’s last assessment, suggest the region will get wetter due to climate change. Yet, in what is known as the ‘East Africa Climate Paradox’ observed trends show the opposite happening (see fig).

Even if ultimately the drying trend goes into reverse, East Africa faces higher temperatures and decades of disruptive climate change. The impact that temperature increases alone will have on agriculture and livestock are likely to be significant, regardless of rainfall changes.’

May 14, 2017

Links I Liked

First up, a spot of self promotion: if you are anywhere near Cape Town, check out my two week July ‘summer school’ on How Change Happens. Details and  links here.

links here.

Don’t like Mondays? Then read this and give thanks (h/t You Had One Job).

Lant Pritchett brilliant on new insights into how China tackled poverty and the implications for Doing Development Differently

Chris Blattman has put slides & reading online for his Order & Violence course. Fantastic resource.

Does foreign aid work? Handy summary of the evidence on a hoary but important topic from Steve Radelet (if anyone is still listening)

Meanwhile, US politics retains its mesmerizing grip:

The Economist interviews the President on economic policy and publishes the transcript. Among other things, he appears to think he invented the term ‘pump-priming’.

‘If young people get together, they can change the world’. Mark Green is President Trump’s very promising nominee for USAID administrator. Here he is in his previous role as Ambassador to Tanzania

Want to speed up your data entry? Hire this guy from the gas station convenience store where he’s been taking inventory for 30 years. [h/t Chris Blattman

NGO = Nothing Going On. This new aid satire looks promising. Here’s the trailer

May 13, 2017

I’m teaching a two week course on Making Change Happen, Cape Town, July. Interested?

Quick heads up. I’m teaching a two week ‘summer school’ (actually more of a winter school) on How Change Happens at the University of Cape Town from

Like this, only colder

17-28th July. Details and registration here. The course will combine a basic intro to the themes of the book with lots of engagement with Cape Town based activists (local Oxfam stars Allan Moolman and Ronald Wesso are helping set up everything from speakers from social movements to visits to interesting ‘sites of struggle’). Brian Levy, governance guru and Academic Director of the UCT Graduate School of Development Policy and Practice, is coming in to talk about how education reform takes place in South Africa, and one of his star students, Chris Nkwatsibwe, will be discussing his experience working with civil society movements in Uganda. And yes, I know this is all male, so we will be making sure of a gender balance when it all goes ahead!

As part of the course, students will be asked to develop a proposal for a particular change process that they would like to see take place. Then we will use the lectures and guest speakers to help refine their proposals and have some kind of Dragon’s Den/X factor competition for the best proposal at the end (with prizes, natch)

Here’s the initial day breakdown (subject to change in a suitably iterative, adaptive kind of way)

Day 1: Interdisciplinary approaches to change and evidence.

Day 2: The nature and implications of Complex Systems.

Day 2: The nature and implications of Complex Systems.

Day 3: Power, culture and social norms – global, national, local

Day 4: Unpacking the state. Recognising the realities of public authority in African contexts.

Day 5: The roles of Political Parties and the rule of law.

Day 6: The international system and the role of large corporations.

Day 7: Civil society and activism.

Day 8: Advocacy, Campaigning and Leadership.

Day 9: Putting it all together to do development differently.

Day 10: Project presentations, discussions and X factor competition to choose the winner.

Interested? Know someone else who might be? If so, please register/forward the link. Maybe see you in Cape Town.

May 11, 2017

Making Change in Closed Political Environments – what works?

I’m a big fan of the International Budget Partnership, which manages both to get down and dirty in supporting national campaigns and movements for  budget transparency, and to step back and spot the broader patterns of politics and change. Over the next few months I’m going to be helping them think through their strategy so I’ve been catching up a few recent research papers.

budget transparency, and to step back and spot the broader patterns of politics and change. Over the next few months I’m going to be helping them think through their strategy so I’ve been catching up a few recent research papers.

First up was ‘“That’s How The Light Gets In”: Making Change in Closing Political Environments’, which pulls together lessons from 3 case studies (India, Kenya and South Africa) and some broader essays by IBP staff and partners to respond to a profound and disorienting state of shock:

‘Almost overnight our trusted champions of open government in Brazil, India, the Philippines, South Africa, and now the United States were replaced by regimes threatening to reverse years of progress in open data, vigorous citizen participation, and the promise of enhanced government accountability. Democracy is under threat the world over.’

The paper asks the right question ‘How do we advance fiscal accountability in an era of closing government?’ because ‘the budget process is also at the core of democratic practice — and the relationship between citizens and the government. While this process can and often does exclude citizens, it can also be a powerful bridge to help citizens move from disaffection to democratic engagement.’

How to build and buttress that bridge? First, recognize the role of crises: ‘Fiscal and governance crises over the past decades have not slowed the trend toward  open budgeting. In fact they have enabled some of the greatest leaps in budget transparency and participation.’

open budgeting. In fact they have enabled some of the greatest leaps in budget transparency and participation.’

IBP ‘sees the light’ in 3 areas of work: ‘refined political strategy, new spaces for impactful work, and new opportunities for powerful alliances’. Some excerpts:

‘Refined Political Strategy

More impactful work in a tougher political environment will require careful attention to local contexts, taking into account political obstacles and unexpected opportunities. For example, a terrible drought in India has made the rural employment scheme vital to a government that otherwise sought to weaken it. Similarly, political violence in Kenya led to a significant decentralization process that has opened up new spaces for vulnerable citizens to contest the budget for people with disabilities.

New Spaces for Impactful Work

At least three new spaces are emerging as opportunities. The first is work on tax and specifically the prevalence of tax havens, illicit flows, and aggressive tax avoidance. These have exploded onto the front pages of newspapers across the globe. At the same time, the Sustainable Development Goals have led donors to pressure countries to replace aid flows with domestic revenues. Although a considerable number of skilled campaigners work on international capital flows, in most parts of the world there is a gap between this global engagement and meaningful civil society participation in revenue debates at the country level. This is a huge opportunity — although it will face organized resistance — for organizations working on national budgets to complement their expenditure work with a greater focus on tax policy and incidence, and the enforcement of tax regimes.

A second area of work with great potential for impact is climate change finance. The emerging opportunity is for expanded civil society engagement at the  country level where IBP partners are strongest, and most able to work with environmental organizations, to ensure that sufficient funds are dedicated to and reach the most vulnerable communities.

country level where IBP partners are strongest, and most able to work with environmental organizations, to ensure that sufficient funds are dedicated to and reach the most vulnerable communities.

The third new space for traction is work at subnational levels of government, with a focus on service delivery. Powerful connections and real gains are possible at state and local levels, even while the national level of government might become more inaccessible.

New Opportunities for Powerful Alliances

One opportunity for powerful, expanded alliances is between civil society organizations, including budget groups, and supreme audit institutions (SAIs). Collaboration between community groups and SAIs has taken many other forms, from fraud hotlines and community involvement in audit site selection, to the publication of popular versions of audit reports and audits jointly conducted by communities and SAIs. Usually this work has been driven by CSOs. What is new is the much greater openness and initiative emerging from the SAIs themselves. As audit reports gather dust on government shelves, more and more activist auditors are turning to partnerships with civil society to overcome their own constraints in encouraging government responsiveness.

The courts are likely to become an even greater asset to civil society budget work in an era of closed government. Where opportunities for partnerships wane, civil society budget groups have been turning, as a last resort, to litigation to secure or protect gains. There is now a much greater body of knowledge and expertise within the budget and broader fiscal community on litigation.’

Really useful stuff

May 10, 2017

Why election politics don’t work as well for the environment as they do for international development

Guest post from Matthew Spencer, who crossed over from the environment sector recently to become Oxfam’s Director of Campaigns and Policy

Before the end of the first week of the UK election campaign, to widespread surprise, Theresa May agreed to the development sector’s main demand to maintain our 0.7% overseas aid commitment. In contrast, the following week the government had to be forced to publish its plan to reduce air pollution by a judge so fed up with its delaying tactics that he instructed ministers to ignore election purdah rules. The first decision helps people who live thousands of miles away, the other obstructs action to address something proven to be killing British voters. It should therefore be easier to get political leadership on environmental health than on international development, but the reverse appears to be true. Why?

As someone who has recently started working for Oxfam after thirty years working in the environment community I’ve been trying to understand the differences between the sectors in order to make sense of these political dynamics.

Unsurprisingly they have very different histories and somewhat different organisational models. Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth were set up in the late 70’s as campaign-only organisations, and their sector has had many political wins on pollution regulation and nature conservation in the decades since. In contrast, the coalition that helped secure the 0.7% commitment from the Prime Minister is made up almost entirely of organisations whose primary mandate is to deliver long-term development programmes and humanitarian aid; campaigning is a very small part of what they do. The differences make sense. If you

Thanks Bill

want to tackle the crisis in particulate air pollution you have to influence the policy of departments of the environment, transport, local government and the Treasury. For every environment issue there are a set of ‘producer’ interests who may be causing the problem, but whose needs will often be uppermost in the minds of government, particularly if they generate employment and tax receipts.

The development sector has an agenda every bit as challenging to economic norms as environmental sustainability, but the vested interests are less obvious and much of its interaction with government has been on overseas aid spending, with occasional forays into finance and trade policy, but a primary focus on spending decisions rather than economic policy.

The environment sector may be more focussed on influencing policy, but it would be wrong to conclude that it is more ‘political’. In my experience the development sector has a more profound understanding of the power dynamics that impede its mission, and a greater commitment to tackling root causes like economic and gender inequality.

The tactical campaigning skill of the environment sector is a great strength but it can also hold it back from a deeper and more compassionate view of the world. As one environmental leader told me, ‘the development sector seems to be better at acknowledging environmental causes of poverty, than the other way around’. Many people in the environment community also believe in social justice, but it is almost absent from their work, in part because it complicates a simple campaign proposition.

There is another difference which helps to explain the fate of those two key policies in the General Election. In theory the campaign savvy and the bigger

and maybe change the tactics too?

public membership of the environment sector should result in bigger electoral success. It rarely does. It is easier for the government to agree to spend billions of pounds on poverty alleviation in Sub-Sahara Africa, than regulate diesel pollution in the streets of Britain precisely because it’s further from voters. Think of it as the proximity paradox. The further away the problem, the easier it feels to resolve the ethics. It’s not contested that absolute poverty in the developing world is wrong, so if the Government wants to look generous and outward looking agreeing 0.7% is an effective signal to the public of those virtues. The morality of diesel pollution at home appears much more complicated because the same citizens whose health is affected may also be enthusiastic car drivers or bus users, or be employed by diesel vehicle manufacturers.

And so to the final difference between the two sectors. The development sector, with strong roots in faith communities, and benefiting from the proximity paradox, is profoundly moral in its language. This is a real strength as politics becomes more narrative and values-driven. The environment sector may have started as an emotional reaction to industrial excess but it now has one foot firmly planted in the instrumental language of technological and economic progress. I know from experience that ‘Better for Britain’ framing works well in Whitehall, but it can also make green solutions vulnerable to public scepticism about technocratic politics.

There are many similarities between the sectors – strong public support even in straitened economic times, deeply committed staff and a strong outcome focus. Both are also threatened by the growth of isolationist populism, whether it expresses itself as fear of refugees or fear of climate action. Neither international development nor the environment are ever likely to be high profile General Election issues, but we both enjoy huge public support, and if we learn from each other we will better withstand the political storms ahead. If the environment sector rekindles its deeper values narrative it will be better able to engage a public sceptical about conventional politics. If the development sector can get better at campaigning on the economic norms that are locking in poverty we will be less at risk of being boxed into a narrow conversation about whether we can afford overseas aid.

May 9, 2017

What is new/the same about the world’s new civic activist movements?

Bumped into Tom Carothers in the DFID foyer the other day, and he handed me a copy of a fascinating new Carnegie Endowment Report, Global Civic  Activism in Flux. Late last year, Carnegie set up a Civic Activism Network that brought together 8 national experts on new forms of citizen activism in Brazil, Egypt, India, Kenya, Thailand, Tunisia, Turkey, and Ukraine, who each contributed chapters. Here’s the rationale, from editor Richard Youngs:

Activism in Flux. Late last year, Carnegie set up a Civic Activism Network that brought together 8 national experts on new forms of citizen activism in Brazil, Egypt, India, Kenya, Thailand, Tunisia, Turkey, and Ukraine, who each contributed chapters. Here’s the rationale, from editor Richard Youngs:

‘Civil society organizations have been subject to considerable criticism and doubt over the past ten years, after enjoying an enormous expansion and heightened attention throughout the developing and post-Communist worlds in the 1990s. Influential observers and analysts in many quarters decry a predominant focus on Western-style nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). They argue that these groups are looking increasingly ineffective, tired, and out of touch—artificial creations often nourished by foreign supporters that lack real domestic constituencies and the ability to sustain themselves locally.

Some of these critics argue that more broadly based citizen movements are starting to reinvigorate the civic sphere, with dynamic and fluid new forms of civic organization emerging and gaining a significant presence in political and social debates. Citizens appear less tolerant of nepotism and corruption, and they are mobilizing through many kinds of campaigns to bear down on self-serving elites. People have also begun to organize themselves within local communities and neighborhoods in search of more equitable decisions about practical, everyday issues. Moreover, information communications technology is generating fundamental changes in the structures of social organization—in the view of some optimistic observers, this is contributing to a seemingly inexorable civic empowerment.

What some analysts refer to as a new contentious politics has taken root. This is not limited to particular regions and regime types, but is increasingly global. Large-scale protests have flared up in scores of states across every region. Many of these appear to have emerged with a degree of spontaneity, involving tens of thousands of citizens who previously were not politically active. Such is their ubiquity that these protests have become a defining feature of modern politics.

The revolts embrace a range of causes. Some are about democratic revolution, some about neoliberalism and globalization, some about specific cases of corruption, and others about very local issues. If their driving motivations are different, so are their outcomes. Some of the new civic mobilizations have ousted regimes; some have won major concessions from incumbent governments; others have failed in their declared aims.’

The country case studies are well worth reading, as is the concluding chapter, identifying five overall messages:

Civil society around the world exhibits a mix of common trends and country-specific changes. In recent years, new actors have emerged with common traits across the eight countries. In each case, civic activism has become more sporadic, footloose, tactically innovative, daring, and intent on carving out local autonomy and ownership, while new forms of civil society also are becoming less dependent on permanent membership

Kenya

structures and less exclusively channelled through traditional NGOs and similar groups. Social movements and individual campaigners are using more creative tactics based on imagery and symbolism. And in all cases, civic activism is adapting to evade governmental controls, as regimes—both democratic and authoritarian—respond nervously and defensively to the new type of contentious politics.

Old and new forms of activism coexist. Analyses about the changing face of civic movements often portray new forms of mobilization as assertively sidelining a discredited arena of traditional activism. The reality appears to be somewhat less clear-cut. New activism has not entirely eclipsed old activism. Nor is new activism quite the kind of purely spontaneous, organization-free phenomenon of popular legend.

While emerging activism is certainly less institutionally rooted than older forms that long depended upon large, membership-based and permanently structured organizations, new activism itself often latches onto organizational structures and evolves over time as it seeks to amplify its reach—or, more defensively, simply to maintain its existence. Kenya, Tunisia, Turkey, and Ukraine all provide examples of old and new activism interacting and influencing each other.

Civil society encompasses both political and practical aims. New civic activism is simultaneously more contentious and more pragmatic. It is both less accommodating of the status quo and more intent in practice on carving out islands of tangible progress and reform. It is driven both by citizens’ increasingly profound frustration with existing political systems and by communities’ desire to find ways of circumventing the constraints of these systems, while these obstacles cannot be immediately removed.

Emerging forms of civil society include both liberal and nonliberal movements. Some new activism is led by leftist radicals, some by conservatives. Some new activism is carried forward by marginalized members of society who seek far-reaching overhauls of entire existing systems, but some activism is undertaken by well-off middle-class groups more concerned with preserving certain features of society….. Interestingly and crucially, new forms of civic activism are both associated with the much commented-on surge in political populism around the world and often aim to push back against this populism.

The effectiveness of civil society movements is closely related to weaknesses stemming from governments’ repressive responses

Ukraine

to them. A key question for future research will be why the new activism appears to have been more—even if not fully—successful in Brazil, Tunisia, and Ukraine than in Egypt, Kenya, or Turkey. There may be no easy single answer to this, although one initial factor that emerges from this report’s eight brief mappings is that there seems to be less polarization among civic actors in the cases of more successful impact. In the cases of Tunisia and Egypt, for example, the spirit of consensus building between civic actors in the former contrasts with the infighting and fragmentation that hampered post-2011 democratic reform in the latter.

New activism is both a cause and an effect of a harsher civic climate. An uncomfortable observation is that the new activism may have become the victim of its own significance—that is, its very success could be narrowing the future prospects of stronger impacts. In nearly all the cases, new activism today is under threat as governments judge it necessary to find ways to neutralize its potential and vibrancy.

May 8, 2017

Blockchain for Development: A Handy Bluffers’ Guide

Top tip: if you’re in a meeting discussing anything to do with finance, at some point look wise and say ‘you do realize, blockchain is likely to change  everything.’ Of course, there is always a terrifying chance that someone will ask what you actually mean. Worry not, because IDS has produced a handy bluffer’s guide to help you respond. Blockchain for Development – Hope or Hype?, by Kevin Hernandez, is the latest in IDS’ ‘Rapid Response Briefings’ series, (which itself is a nice example of how research institutions can work better around critical junctures/windows of opportunity). It’s only four pages, but in case even that is too onerous, here are some excerpts (aka a bluffer’s guide to the bluffer’s guide).

everything.’ Of course, there is always a terrifying chance that someone will ask what you actually mean. Worry not, because IDS has produced a handy bluffer’s guide to help you respond. Blockchain for Development – Hope or Hype?, by Kevin Hernandez, is the latest in IDS’ ‘Rapid Response Briefings’ series, (which itself is a nice example of how research institutions can work better around critical junctures/windows of opportunity). It’s only four pages, but in case even that is too onerous, here are some excerpts (aka a bluffer’s guide to the bluffer’s guide).

‘What is blockchain technology?

At its heart, the blockchain is a ledger. It is a digital ledger of transactions that is distributed, verified and monitored by multiple sources simultaneously. It may be difficult to think of something as basic as the way we keep and maintain records as a technology, but this is because record-keeping is so ingrained in daily life, albeit often invisibly. The ubiquity of ledgers is in part the reason why blockchains are held as having so much disruptive potential. Traditionally, ledgers have enabled and facilitated vital functions, with the help of trusted third parties such as financial institutions and governments. These include: ensuring us of who owns what; validating transactions; or verifying that a given piece of information is true.

Table 1: Comparing traditional ledgers with the blockchain

The hype is not about the blockchain itself but what it enables. It has been called ‘the trust protocol’ because it facilitates trust between people without the need for an intermediary to verify and/or validate identities, funds, or ensure compliance. Since ledgers are so ubiquitous, blockchains can disrupt just about every sector. It goes beyond money. Any unit of value can be transacted on blockchains. Some are calling it ‘the second era of the internet’ or the ‘economic layer the internet never had’.

Potential development applications

Microfinance: Anyone using the blockchain application bitcoin has the equivalent to an online bank account in the form of a bitcoin wallet. Getting a bitcoin wallet is free and it is available to anyone with internet access. Some wallet providers are working on SMS solutions. No legal identification is required, just an email address or phone number, and there are no maintenance fees or minimum balance requirements. However, digital inequalities mean blockchain banking may be less accessible to those less likely to be online, such as poorer communities, women (especially in developing countries) and minorities.

Remittances and international payments: Blockchain transactions are borderless. The same minimal fee (a few US cents) is charged regardless of where the two sides of a transaction reside. Currently the average remittance cost is 7.6 per cent globally but can cost up to 20 per cent – depending on the sending and receiving country. The World Bank estimates that cutting the cost by 5 percentage points can save US$16bn per year.

Digital registries: As an immutable, time-stamped ledger, the blockchain is an attractive tool to prove ownership and existence. There are already  initiatives aiming to use blockchains to register land and improve property rights, including Bitfury in Georgia and Factom in Honduras. Registering assets may allow people in developing countries to leverage up to US$20tn (as estimated by economist Hernando de Soto) for capital which they do not currently have proof of ownership for. Furthermore, the blockchain can be used to track assets from raw materials to the end user to ensure they meet standards (e.g. organic or fair trade).

initiatives aiming to use blockchains to register land and improve property rights, including Bitfury in Georgia and Factom in Honduras. Registering assets may allow people in developing countries to leverage up to US$20tn (as estimated by economist Hernando de Soto) for capital which they do not currently have proof of ownership for. Furthermore, the blockchain can be used to track assets from raw materials to the end user to ensure they meet standards (e.g. organic or fair trade).

Tracking aid: The blockchain can help give governments and taxpayers piece of mind as it makes it possible to track aid funds in near-real time through the aid chain, allowing donors to ensure money is being spent as intended and to crack down on misappropriated funds.

Smart-aid contracts: Smart contracts are essentially bank accounts for contracts that live on blockchains in the form of computer code with instructions that self-execute and automatically disperse funds once predetermined conditions are met. This can potentially streamline results-based finance. Funds can be automatically dispersed as objectives and milestones are reached, albeit such rigid forms of financing can make it even more difficult to adapt to complex contexts and issues. Smart contracts could also help improve response time to crises by automatically dispersing predetermined amounts of funds after a certain amount of deaths during an epidemic or if a natural disaster of a predetermined magnitude hits a vulnerable country.

P2P aid: Peer-to-peer (P2P) donations could be made via blockchain without the help of aid organisations, NGOs, community organisations, or any other intermediaries in the aid chain as well as financial institutions. This could ensure that a larger share of donations and loans reach beneficiaries, and smart contracts can be built into them to ensure money is used as intended (e.g. sending kids to school). However, overreliance on such models could leave out digitally poor groups unable to upload their stories onto P2P platforms.’

The report sets out a ten point checklist for policy makers, which I found a bit underwhelming, tbh, but this eminently sensible para did stand out:

‘Given that context is important in determining what will work, be sceptical of outsider blockchain solutions to local problems. Remote design or sending people for short periods of time to set up blockchain solutions is likely to be inadequate. Successful blockchain applications are likely to be those designed in developing countries putting the end user at the centre of the design process, not those designed for developing countries.’

One final suggestion. Blockchain lends itself to individual contracts (see ref to de Soto), but presumably it would be technically feasible, and probably politically worthwhile, to come up with some kind of collective version that could, for example, prove communal land ownership when communities are subject to land grabs? Anyone working on that?

And if you want more, here is a similar ‘blockchain for beginners’ piece from the World Economic Forum – maybe a bit more accessible, but fewer cautionary notes

May 7, 2017

Links I Liked

Inequality slot: Wealth concentration and inequality in China are much worse than we thought, according to Thomas Piketty & friends, using new data  sources.

sources.

Branko Milanovic in the new Guardian inequality website on why we should care about inequality, and what is likely to happen next

The arguments over US aid are escalating – 43 US senators signed an open letter calling for protection of foreign aid budget. The Brookings Institution (a think tank) summed up the impact of President Trump’s first 100 days on Africa: Security is number 1; bad news on family planning; 13% aid cut (100% in CAR, Sierra Leone and Niger)

Nice Helvetas report (blog + voxpops) on my recent book launch at the wonderful ETH building in Zurich

Could insurance companies be about to stop insuring fossil fuel projects, with massive consequences?

I saw ‘Citizen Jane: The Battle for the City’ at the weekend. Brilliant documentary on the life of Jane Jacobs – a great systems thinker. Catch it if you can. Going to have to reread The Death and Life of Great American Cities

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers