Duncan Green's Blog, page 120

April 19, 2017

What does Systems Thinking tell us about how INGOs and Academics can work together better?

Yesterday, I wrote about the obstacles to NGO-academic collaboration. In this second of three posts on the interface between practitioners and

You are where exactly?

researchers, I look at the implications of systems thinking.

Some of the problems that arise in the academic–INGO interface stem from overly linear approaches to what is in effect an ideas and knowledge ecosystem. In such contexts, systems thinking can help identify bottlenecks and suggest possible ways forward.

Getting beyond supply and demand to convening and brokering

Supply-driven is the norm in development research – ‘experts’ churning out policy papers, briefings, books, blogs etc. Being truly demand-driven is hard even to imagine – an NGO or university department submitting themselves to a public poll on what should be researched? But increasingly in areas such as governance or value chains, we try and move beyond both supply and demand to a convening/brokering role, bringing together different ‘unusual suspects’ – what would that look like in research? Action research, with an agenda that emerges from an interaction between communities and researchers? Natural science seems further ahead on this point: when the Dutch National Research Agenda ran a nationwide citizen survey of research questions they wanted science to look at, 12,000 questions were submitted and clustered into 140 questions, under seven or eight themes. To the organisers’ surprise, many citizens asked quite deep questions.

Most studies identify a need for ‘knowledge brokers’ not only to bridge the gap between the realms of science and policy, but also to synthesise and transform evidence into an effective and usable form for policy and practice, through a process akin to alchemy. An essential feature of knowledge brokers is that they understand the cultures of both worlds. Often, this role is performed by third-sector organisations of various types (from lobbyists to thinktanks to respected research funders). Some academics can transcend this divide. A few universities employ specialist knowledge brokers, but their long-term effectiveness is often constrained by low status, insecure contracts and lack of career pathways. Whoever plays this crucial intermediary role, it appears that it is currently under-resourced within and beyond the university system. In the development sector, the nearest thing to an embedded gateway is the Governance and Social Development Resource Centre (GSDRC), run by Birmingham University and IDS and largely funded by the Department for International Development. It conducts literature and evidence reviews on a range of topics, drawing evidence from both academic literature and non-academic institutions.

Critical junctures

Anyone involved in advocacy knows that the openness of policymakers to new ideas is episodic, and linked to things such as changes of administration, scandals, crises and failures, known in the political science literature as critical junctures. Currently, thinktanks are reasonably good at responding to the windows of opportunity presented by such moments, updating and repackaging previous research for newly attentive policymakers or providing rapid informed commentary (see, e.g. on Brexit, Collin and Juden 2016; ODI 2016). In contrast, universities are often much more sluggish, trapped by the long cycle of research and dissemination, and with few incentives to drop or adapt existing work to respond to new opportunities. What would need to change in terms of incentives or leadership to make universities as agile as thinktanks?

Precedents: history and positive deviance

Precedents: history and positive deviance

The development community spends little time thinking about what has already worked, either historically or today. Research could really help fill in historical gaps, whether on campaigns or redistribution. It also makes little use of ‘positive deviance’ approaches, which identify positive outliers: where good things are already happening in the system, for example identifying and studying villages with lower than average rates of maternal mortality and then trying to find out why.

Feedback, adaptation and course correction

In systems, initial interventions are likely to have to be tweaked or totally overhauled in light of feedback from experience or events. Yet both academics and INGOs still portray their research papers as tablets of stone – the last word on any given topic. Digital technology allows us to make them all ‘living documents’, subject to periodic revision. At the very least, publishing drafts of all papers for comments both improves quality and builds bridges between researchers, practitioners and policymakers, as the author has discovered on numerous occasions.

Engage with whole systems not just individuals

Reflecting on Oxfam’s Make Trade Fair campaign in the early 2000s, Muthoni Muriu concluded:

You need to engage different policy makers, on different aspects of the same policy, sometimes in different geographies, to create the sort of critical mass that will drive conversation and hopefully decisions in the desired direction. One or two ‘validation’ workshops or conference won’t do it. Our experience… was that we needed to speak with technocrats in the Ministries of Agriculture, Trade, Planning and Foreign affairs, relevant embassy trade advisers (and ambassadors) in Brussels and Geneva; trusted policy institutions; random academics working for CIDA/SIDA/DFID etc who had connections with said ministries; equally random World Bank/IMF/EU commission folks in-country; friendly journalists etc etc… to get the Minister of Trade to take a position on one policy recommendation!

Tomorrow: What to do about it

April 18, 2017

What are the obstacles to collaboration between NGOs and Academics?

I wrote a chapter on the NGO-Academia Interface for the recent IDS publication, The Social Realities of Knowledge for Development, summarized here by James Georgalakis. It’s too long for a blog, but pulls together where I’ve got to on this thorny topic, so over the next few days, I will divvy it up into some bite-sized chunks for FP2P readers.

First, why collaboration between NGOs and academics ought to be easy, but in practice is really difficult:

The case for partnership between International Non-Governmental Organizations (INGOs) and academia to advance development knowledge is strong.  INGOs bring presence on the ground – through their own operations or long-term local partnerships – and communication and advocacy skills (which are not always academics’ strong point). Academia contributes research skills and credibility, and a long-term reflective perspective that the more frenetic forms of operational work and activism often lack.

INGOs bring presence on the ground – through their own operations or long-term local partnerships – and communication and advocacy skills (which are not always academics’ strong point). Academia contributes research skills and credibility, and a long-term reflective perspective that the more frenetic forms of operational work and activism often lack.

In practice, however, such partnerships have proven remarkably difficult, partly because, if anything, INGOs and academia are too complementary – there is so little overlap between their respective worlds that it is often difficult to find ways to work together.

Obstacles to Collaboration

Impact v Publication: While funding incentives push academics towards collaboration with INGOs and other actors able to deliver the elusive ‘impact’, other disciplinary and career pressures appear to push in the opposite direction. The rather closed nature of academia’s epistemic communities, buttressed by shared and often exclusive language and common assumptions, deters would-be collaborators, while the pressure to publish in peer-reviewed journals and acquire a reputation within a given discipline shift incentives away from collaboration with ‘outsiders’.

Urgency v Wait and See: INGOs’ focus is urgent, immediate and often in response to events. They prefer moving quickly and loudly – reaching as many people as possible, and influencing them – without necessarily having time for slower forms of academic engagement. Academics work to a different rhythm, both in terms of the issues, and the way they respond to them. When Oxfam won some research funding with IDS to explore food price volatility, it was top of our advocacy agenda, but food prices calmed down, the campaigns spotlight moved on, and the resulting research, though interesting, struggled to stay connected to Oxfam’s evolving agenda.

For small NGOs, whether national or international, research support is absent when it is most needed – during the design and implementation of projects. Instead, researchers often only show up when the organisation has developed some ‘good practice’ and then only to document the outcomes.

Status Quo v Originality: INGOs do need good research to tell them what is going well, or badly, what they need to do more of, less of etc. But also (and increasingly) they need targeted research to help prove to donors that they are value for money. This often means validating the status quo. Researchers on the other hand may be looking to find a new angle, move a debate on and (perhaps too cynical?) make a name for themselves amongst their peers. These agendas can occasionally be complementary, but in practice often lead to tension, with INGOs experiencing researchers as unhealthily preoccupied with ‘taking down’ success stories and attacking aid agencies’ performance and legitimacy, often on the flimsiest of evidence.

Status Quo v Originality: INGOs do need good research to tell them what is going well, or badly, what they need to do more of, less of etc. But also (and increasingly) they need targeted research to help prove to donors that they are value for money. This often means validating the status quo. Researchers on the other hand may be looking to find a new angle, move a debate on and (perhaps too cynical?) make a name for themselves amongst their peers. These agendas can occasionally be complementary, but in practice often lead to tension, with INGOs experiencing researchers as unhealthily preoccupied with ‘taking down’ success stories and attacking aid agencies’ performance and legitimacy, often on the flimsiest of evidence.

Thinking v Talking: Research is very underfunded in INGOs and is distributed across organizations. In Oxfam GB, the policy research team behind its high profile research papers on inequality for Davos, and other impressive work, has just 8 staff. By contrast, the Oxfam head of research, Irene Guijt, has calculated that countries belonging to the OECD have 5.5 million full time academics. There are lots of smart researchers working elsewhere within Oxfam – on programme monitoring, evaluation, learning, or doing research as part of their advocacy roles, but even then, by one calculation, across the whole of Oxfam International, research staff come to just 7% of communications staff (a cynic might say we prize talking 14 times more than thinking…..). Hardly surprising then that it is really hard to engage with academics, even if it’s just to make meetings to explore options .

Tomorrow: What to do about it?

April 17, 2017

Links I Liked

I’m running a two week summer school on How Change Happens in Cape Town in July. Sign up here.

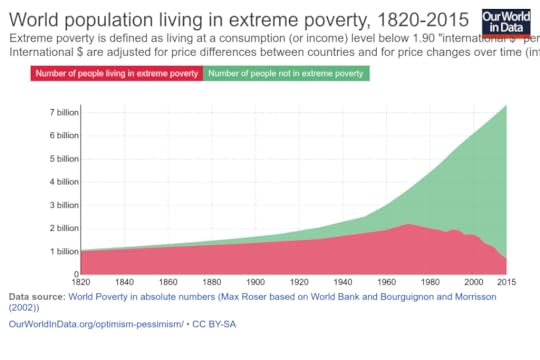

Newspapers should have had the headline “Number of people in extreme poverty fell by 137,000 since yesterday.” Every day for the last 25 years [h/t Max Roser]

New Oxfam report. From 2009-2015, the 50 biggest US companies received over $423 billion in tax breaks; Over that time they spent over $2.5 billion on lobbying Congress. Now that’s what I call a return on investment.

If US – North Korea tensions continue to escalate, it is worth remembering their exceptionally bloody history [h/t Jeffrey Kaye]

If US – North Korea tensions continue to escalate, it is worth remembering their exceptionally bloody history [h/t Jeffrey Kaye]

“I see her as the John Maynard Keynes of the 21st century”. George Monbiot really likes Doughnut Economics

One Indian’s 17 year struggle to prove he wasn’t dead. He ended up founding the Uttar Pradesh Association of Dead People. Eat your heart out Gogol.

The 2016 aid numbers from the OECD (29 of the world’s wealthiest countries) are now in. Headlines: total aid was $142.6bn in 2016, 9% up on 2015. A quarter of the increase went on refugee costs within donor borders. With very little fanfare, Germany became the second G7 country (after UK) to reach the 0.7% aid target.

Announcing Unpaywall: unlocking Open Access versions of paywalled research articles as you browse

Loving Dilbert’s descent into the jargon matrix. Time for an aid version? I’m putting Robert Chambers down for Morpheus, every fuzzword-spouting aid bureaucrat you’ve ever met as Agent Smith, but who can play Neo, the leather-clad Messiah who can vanquish aidspeak make development intelligible again?

April 12, 2017

Drought in Africa – How the system to fund humanitarian aid is still hardwired to fail

Guest post from Debbie Hillier, Oxfam Humanitarian Policy Adviser

Nearly 11 million people across Ethiopia, Somalia and Kenya are facing alarming levels of food insecurity. In Somalia, deaths as a result of drought have already been recorded, and as its next rains are forecast to be poor, famine is a real possibility. But why are we facing the threat of famine yet again in Somalia?

Severe hunger and famine do not arrive suddenly or unexpectedly. In 2017, as always, they have been months in the making. But the deaths already seen from hunger and associated disease in Somalia have not been prevented, and the threat of famine has not been averted, because as we’ve learnt so often before, humanitarian aid only arrives at speed and scale when there is massive visible suffering.

That’s what happened in Somalia in 2011. The money rolled in only after famine was declared. By then, for many, it was already too late.

Numbers of people needing assistance in Somalia and cumulative appeal funding. Red lines represent FEWS NET and FSNAU special early warning products

Numbers of people needing assistance in Somalia and cumulative appeal funding. Red lines represent FEWS NET and FSNAU special early warning products

We know all too well that early response to drought saves lives – and is much cheaper. In October 2015, it was estimated that a late response to the El Niño drought in Ethiopia would cost $1.7bn whereas an early response would cost only $720m. Altogether around the world, the same author, Courtenay Cabot Venton, estimates that early funding for food procurement could save $2bn of the approximate $10bn that is spent on food aid each year.

These represent huge savings – of money and lives. So why isn’t anyone listening?

The way that humanitarian aid is funded is simply not set up to respond to early warnings of crisis. Government donors respond when the needs are acute, and many respond generously when it is splashed over the news. But that money is not available to prevent crises, when the forecasts are looking bad.

The international community collectively said ‘never again’ after 260,000 people died in the Somalia famine in 2011. Even in Ethiopia and Kenya, where the impact was much reduced, the DEC evaluation called the response a ‘system-wide failure’ resulting in ‘far greater suffering than was necessary.’

So has anything improved since then? There have been some innovations:

Kenya’s Hunger Safety Net Programme which supports the most vulnerable people in northern arid areas of Kenya is scalable – it can provide cash to more people to support them in drought or flood. It uses objective, scientific triggers to scale up and down, and can transfer cash within two weeks.

The Red Cross movement and Climate Centre have been piloting Forecast-based Financing in several countries, including Peru, Mozambique, Bangladesh and the Philippines, where pre-agreed thresholds (eg of river levels, temperature) automatically trigger a pre-agreed response.

What about more recent experience? In the 2015/16 El Niño, the response was considerable in many countries, but inadequate to the size of the challenge.

But we do delay, every time.

Some donors acted early – eg in Ethiopia, DFID redirected some funding from long-term programmes to emergency response in July 2015 (two months after the El Niño was confirmed and before needs had escalated). But even in Ethiopia, where there is ample experience of drought response and systems and structures ready to respond, research found that late procurement of food cost donors an additional $127m, which could have provided food aid to an additional 1.4m people.

So there is still a long way to go. We need a shift to predictable funding for predictable costs. This is not about more money but funding earlier. The evidence is overwhelming and unequivocal that early action saves costs in three ways – it reduces human suffering, it reduces humanitarian expenditure, and it prevents development losses.

What is needed:

A global fund for early action. Most donors have speedy funding mechanisms for rapid onset crises, such as earthquakes or hurricanes, but no donors have a similar mechanism for early action. Humanitarian donors prioritise based on needs, funnelling funding to acute crises, and away from preventing tomorrow’s crisis.

A shift in political incentives to enable donors to support early action. British taxpayers need to understand that funding early action to prevent crises is much cheaper and better than late emergency relief. Perhaps an Early Action Scorecard for donors could be developed to provide a political cost to inaction?

Taking the political decision-making out. Pre-agreed and objective thresholds should be developed that automatically trigger funding and appropriate response. This can build on the experience of forecast-based financing, taking these pilots up to scale.

Shock-responsive programmes that can expand and contract like an accordion in response to changing situations. Using existing programmes, partners and contracts to deliver an early response is preferable to creating a parallel humanitarian structure which is likely to be inefficient, late and more costly.

To respond to the crisis in the Horn right now, what is needed is a massive injection of aid, backed with diplomatic clout and driven by the imperative to save lives. Action now can prevent a catastrophic loss of life. Donors must not wait for a famine declaration before responding. It is sobering to note that in the Somalia famine of 2011, around half of the 260,000 deaths occurred in April-May, before famine was declared.

To prevent the next forecast crisis, we need a recognition that the current system is not fit for purpose and concerted efforts to address this. Humanitarians need to prioritise funding for early response; development agencies need to design programmes that can reduce risk and vulnerability and donors need to be braver, using their funding in the most cost effective way possible for prevention, even if that doesn’t get media attention.

April 11, 2017

Tortoise v Hare: Is China challenging the US for global leadership? Great Economist piece

Back from Australia and I’ve been catching up on my Economist backlog. The 1st April edition exemplified the things the magazine does really well (I don’t  include its naff geek-humour April 1st leader supporting a tax on efficiency). There were the customary great infographics – here’s the map showing the extent to which countries export/import air pollution through their trade in goods (i.e. importing dirty stuff rather than making it at home).Next up, an overview on global progress in eradicating extreme poverty (and how much harder it gets as you get closer to zero – the ‘last mile problem’). Here’s a flavour:

include its naff geek-humour April 1st leader supporting a tax on efficiency). There were the customary great infographics – here’s the map showing the extent to which countries export/import air pollution through their trade in goods (i.e. importing dirty stuff rather than making it at home).Next up, an overview on global progress in eradicating extreme poverty (and how much harder it gets as you get closer to zero – the ‘last mile problem’). Here’s a flavour:

‘Until recently the world’s poorest people could be divided into three big groups: Chinese, Indian and everybody else. In 1987 China is thought to have had 660m poor people, and India 374m. The concentration of destitution in those two countries was in one sense a boon, because in both places better economic policies allowed legions to scramble out of poverty. At the last count (2011 in India; 2013 in China) India had 268m paupers and China just 25m. Both countries are much more populous than they were 30 years ago.’

But the standout piece was subtitled ‘Is China challenging the US for global leadership?’, ahead of the strikingly low key Trump-Xi summit (post mortem here). Here are some excerpts:

But the standout piece was subtitled ‘Is China challenging the US for global leadership?’, ahead of the strikingly low key Trump-Xi summit (post mortem here). Here are some excerpts:

‘They are looking in opposite directions: America away from shouldering global responsibilities, China towards it. And they are reappraising their positions in very different ways. Hare-like, the Trump administration is dashing from one policy to the next, sometimes contradicting itself and willing to box any rival it sees. China, tortoise-like, is extending its head cautiously beyond its carapace, taking slow, painstaking steps. Aesop knew how this contest is likely to end.

China’s guiding foreign-policy principle used to be Deng Xiaoping’s admonition in 1992 that the country should “keep a low profile, never take the lead…and make a difference.” This shifted a little in 2010 when officials started to say China should make a difference “actively”. It shifted further in January when Mr Xi went to the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, and told the assembled throng that China should “guide economic globalisation”. Diplomats in Beijing swap rumours that a first draft of Mr Xi’s speech focused on the domestic economy, an uncontroversial subject that Chinese leaders usually like to talk about abroad. Mr Xi is said to have rejected this version, and brought in foreign consultants to write one dwelling more on China’s view of the world…..

Is China challenging America for global leadership?

To answer that, it is important to begin with the way China’s political system works. Policies rarely emerge fully formed in a presidential speech. Officials often prefer to send subtle signals about intended changes, in a way that gives the government room to retreat should the new approach fail. The signals are amplified by similar ones further down the system and fleshed out by controlled discussions in state-owned media. In the realm of foreign policy, all that is happening now.[image error]

State-run media have begun to discuss the makings of an idea that, unlike the old one of a China model, the country would like to sell to others. This is the so-called “China solution”. The phrase was first mentioned last July, on the 95th anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party. Mr Xi’s celebratory speech asserted that the Chinese people were “fully confident that they can provide a China solution to humanity’s search for better social institutions”. The term has gone viral. Baidu, China’s most popular search engine, counts 22m usages of its Chinese rendering: Zhongguo fang’an.

No one has defined what the China solution is. But, whatever it means, there is one for everything. Strengthening global government? There is a China solution to that, said the People’s Daily, the party’s main mouthpiece, in mid-March. Climate change? “The next step is for us to bring China’s own solution,” said Xie Zhenhua, the government’s special climate envoy, in another newspaper, Southern Metropolis. There is even a China solution to the problem of bolstering the rule of law, claimed an article in January in Study Times, a weekly for officials. Multi-billion-dollar investments in infrastructure in Central Asia are China’s solution to poverty and instability there. And so on. Unlike the China model, which its boosters said was aimed at developing countries, the China solution, says David Kelly of China Policy, a consultancy, is for everyone—including Western countries.

But talk of “guiding globalisation” and a “China solution” does not mean China is turning its back on the existing global order or challenging American leadership of it across the board. China is a revisionist power, wanting to expand influence within the system. It is neither a revolutionary power bent on overthrowing things, nor a usurper, intent on grabbing global control.

So what might China’s unassuming new assertiveness mean in practice? A template can be found in climate-change policy. China was one of the main obstacles to a global climate agreement in 2008, but now its words are the lingua franca of climate-related diplomacy. Parts of a deal on carbon emissions between Mr Xi and Barack Obama were incorporated wholesale into the Paris climate treaty of 2016. China helped determine how that accord defines what are known as “common and differentiated responsibilities”, namely how much each country should be responsible for cutting emissions.

So what might China’s unassuming new assertiveness mean in practice? A template can be found in climate-change policy. China was one of the main obstacles to a global climate agreement in 2008, but now its words are the lingua franca of climate-related diplomacy. Parts of a deal on carbon emissions between Mr Xi and Barack Obama were incorporated wholesale into the Paris climate treaty of 2016. China helped determine how that accord defines what are known as “common and differentiated responsibilities”, namely how much each country should be responsible for cutting emissions.

As chairman of the G20 last year, Mr Xi made the fight against climate change a priority for the group. But China’s clout at that time was bolstered by its accord with America. Now Mr Trump is beginning to dismantle his predecessor’s climate policies. Li Shou of Greenpeace says China is therefore preparing to go it alone as Mr Xie, the climate envoy, said in January that it was prepared to do. It may be that a “China solution” to climate change will be the first practical application of the term.

Soon after Mr Xi’s speech in Davos, Zhang Jun, a senior Foreign Ministry official, put his finger on China’s changing place in the world. “I would say it is not China rushing to the front,” he told a newspaper in Hong Kong, “but rather the front-runners have stepped back, leaving the place to China.” But officials have far fewer qualms than Deng did about being at the front. “If China is required to play a leadership role,” says Mr Zhang, “it will assume its responsibilities.”’

April 10, 2017

Need your advice: is it worth doing a new edition of From Poverty to Power?

Through previous exercises in consultation, I’ve developed a great respect for the wisdom of the FP2P hivemind, so thought I would ask your advice about  whether to update From Poverty to Power (the book).

whether to update From Poverty to Power (the book).

For those who haven’t read it, the book is a bit of a compendium on development, with sections on power and politics; poverty and wealth; human security and the international system. Initially published in 2008, the second edition of FP2P came out in 2012, complete with a new (brief) section on the ‘food and financial crises of 2008-11). The back cover blurb summarizes the book’s core argument:

‘FP2P argues that a radical redistribution of power, opportunities and assets, rather than traditional models of charitable or government aid is required to break the cycle of poverty and inequality. Active citizens and effective states are driving this transformation.

Why active citizens? Because people living in poverty must have a voice in deciding their own destiny and holding the state and the private sector to account. Why effective states? Because history shows that no country has prospered without a state structure that can actively manage the development process.’

2012 means that it’s looking a little old – stuff keeps happening, ideas evolving (including my own). If I don’t update it, it will enter that slow decline into oblivion that awaits the vast majority of books: universities will adopt more recent books on similar topics, old copies of FP2P will gather dust on shelves or continue to prop up computer screens in Oxfam offices across the world (I fear this may turn out to be FP2P’s most enduring legacy…….).

Probably the only person who cares about this is the author, so I’m wondering whether to do a third edition.

Case for:

It’s a lot easier to update an existing book than write a new one.

The book is established on a number of course reading lists, so the market is more certain than for a new book, and promotion won’t entail the kind of knackering promo tours that I’ve been doing for How Change Happens.

Case against:

The opportunity costs of time and effort, which I could be using for something else

Each new edition gets a bit more clunky, if you just update existing chapters. And the book is already very long (470 pages)

An option would be to rewrite the book, rather than just update it, but that is much more work, and runs the risk of making it look much more like How Change Happens, since that reflects most of my current thinking on aid and development. Paul O’Brien of Oxfam America nailed the relationship between the two books better than I possibly could: FP2P is all about the boxes in the theory of change diagram (active citizens, effective states); HCH is all about the arrows in between.

In particular, if you are familiar with the book or using it for teaching or any other purpose, what do you think? Any advice (e.g. on what needs to be changed, added or removed) in comments welcome, but it’s also time for a new poll, so here you go (and you can vote for more than one option).

Note: There is a poll embedded within this post, please visit the site to participate in this post's poll.

And here’s the original trailer for the book, which I still love

April 9, 2017

Links I Liked

Back from a busy two weeks in Aus and NZ, including this interview with Lisa Cornish of DevEx, recorded under the eucalyptus trees of Canberra.

For writers of long emails everywhere. Please don’t.

In which h/t Prof David Hudson

Chuffed that the Economist ran my letter on inequality. Shame they cut all mention of Oxfam though.

Maybe the true challenge of Islamism to the West is that it challenges the centrality of the nation state.

‘UK government under fire for failure to regulate aid contractors’. Some uncritical ‘private sector = good, everyone else = rubbish’ chickens coming home to roost. Trouble is, the reputation and quality of aid suffers in the process.

Why it matters to understand the informal economy. Lovely prize-winning essay from LSE_ID student Max Gallien

The highlight in Australia was probably being roasted in front of 200 people in Melbourne by my good friend Chris Roche. As a finale he made me proceed up the stairs to sign books, while on the big screen appeared Slim Dusty singing ‘I love to have a beer with Duncan’. Memorably weird.

April 6, 2017

Could New Zealand become the Norway of the South on aid and diplomacy?

Spent last week in New Zealand, involved in some fascinating, if jetlag-bleary, conversations  with both Oxfam and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade (MFAT), which manages NZ’s $400m aid budget. What emerged was that both Oxfam NZ and MFAT have what it takes to become ‘innovation hubs’ within their respective sectors. That means they are smart enough and small enough to be able to come up with new things to try out in their main area of operations, which are the Pacific Islands like Samoa, Fiji or Kiribati. (Small populations, massive distances and facing serious threats both in terms of building viable economies and rising sea levels).

with both Oxfam and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade (MFAT), which manages NZ’s $400m aid budget. What emerged was that both Oxfam NZ and MFAT have what it takes to become ‘innovation hubs’ within their respective sectors. That means they are smart enough and small enough to be able to come up with new things to try out in their main area of operations, which are the Pacific Islands like Samoa, Fiji or Kiribati. (Small populations, massive distances and facing serious threats both in terms of building viable economies and rising sea levels).

The discussions at MFAT were particularly interesting. According to a global poll of aid recipients, among bilateral donors, NZ shines in terms of the usefulness of its advice, its agenda-setting influence, and its helpfulness with implementing reforms. It is seen as small, respectful, and at ease with working with different cultures and traditions. Perhaps most important, it is Not Australia (seen as a colonial power in parts of the Pacific).

What also struck me in conversations at MFAT was that the integration of its foreign and aid ministries, following a merger in 2009, could prove an asset in developing such a role. Diplomats are much more comfortable talking about politics, power and influence. In many ways the kinds of power and systems approach I was presenting to them fits more easily with their traditions, than with the economistic focus on data, evidence and project planning that dominates the thinking of traditional aid agencies.

What also struck me in conversations at MFAT was that the integration of its foreign and aid ministries, following a merger in 2009, could prove an asset in developing such a role. Diplomats are much more comfortable talking about politics, power and influence. In many ways the kinds of power and systems approach I was presenting to them fits more easily with their traditions, than with the economistic focus on data, evidence and project planning that dominates the thinking of traditional aid agencies.

On the other hand diplomats and aid workers have vastly different time horizons. Foreign Policy is typically short term and reactive, while aid tries to be a bit longer term (although still too short termist for my taste) and proactive. The relatively small size of MFAT means that diplomats and aid types might find it easier than larger bilateral to learn from each other and come up with a combined approach that brings together the best of their two worlds.

That way of working could be that NZ picks up the adaptive management/doing development differently agenda and runs with it. Just as some of the smaller NGOs like Local First have done some of the most interesting work, so New Zealand could build on its pioneering background (first country for women to have the vote and one of the first state pension schemes) and become a pioneer on finding new ways to think and work politically in development, and avoid some of the traditional downsides of aid (big, inflexible money, beset with conditions, risk averse, regulations and reporting requirements).

For example, NZ could become a sort of Norway of the South – small enough to be agile, focussing on conflict resolution, mediation, honest broker roles in a region with more than its fair share of conflicts, climate change driven emergencies and political crises. That could also mean less beating of the drum for NZ Inc, but a change of minister in May and an election in September could provide just the Window of Opportunity to redesign their strategy. Fingers crossed.

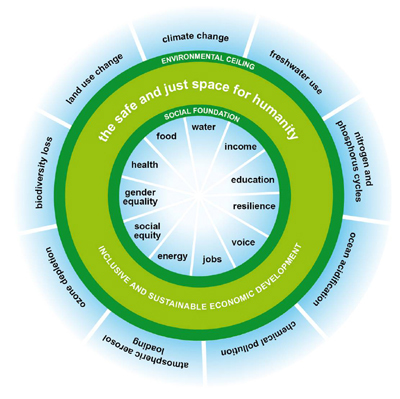

Review of Doughnut Economics – a new book you will need to know about

My Exfam colleague Kate Raworth’s book Doughnut Economics is launched today, and I think it’s going to be big. Not sure just how big, or whether I agree  with George Monbiot’s superbly OTT plug comparing it to Keynes’s General Theory. It’s really hard to tell, as a non-economist, just how paradigm-changing it will be, but I loved it, and I want everyone to read it.

with George Monbiot’s superbly OTT plug comparing it to Keynes’s General Theory. It’s really hard to tell, as a non-economist, just how paradigm-changing it will be, but I loved it, and I want everyone to read it.

Down to business – what does it say? The subtitle, ‘Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist’, sets out the intention: the book identifies 7 major flaws in traditional economic thinking, and a chapter on each on how to fix them. The starting point is drawings – working with Kate was fun, because whereas I think almost entirely in words, she has a highly visual imagination – she was always messing around with mind maps and doodles. And she’s onto something, because it’s the diagrams that act as visual frames, shaping the way we understand the world and absorb/reject new ideas and fresh evidence. Think of the way every economist you know starts drawing supply and demand curves at the slightest encouragement.

Her main target is GDP (the standard measure of national economic output), and its assumptions – an open systems approach to economics that ignores planetary boundaries as it promotes economic growth. Her breakthrough moment while at Oxfam was coming up with ‘the doughnut’ – two concentric rings representing the planetary ceiling and minimum standards for all human beings. The ‘safe and just space’ between the two rings is where our species needs to be if it wants to make poverty history without destroying the planet.

When Kate came up with the doughnut in a highly influential 2012 paper for Oxfam, my non-visual mind failed to grasp its full value. After all, wasn’t this just a restatement of the idea of sustainable development? But it went viral, especially at the UN, because it allowed activists and policy makers to visualize both the threats and how they were trying to overcome them.

The other 6 main chapters cover:

‘See the big picture’: seeing the economy as ‘embedded’ in wider social and environmental systems

A critique of individualist ‘rational economic man’ that redraws the object of economics as social, adaptable humans

Moving from equilibrium economics to complex adaptive systems

Forget Kuznets: growth won’t lead to falling inequality – the economy must be ‘distributive by design’

Forget Kuznets II: growth won’t clean up the environmental damage it helps cause – the economy needs to be ‘regenerative by design’

Where does growth fit? Need to move from the current financial, political and social addiction to growth, to allowing GDP to adjust up, down, or oscillate, as the economy transforms

These bald summaries do no justice to the writing (Kate writes beautifully – leaving Oxfam seems to have liberated her), or the content (see last week’s posted extracts for a taste). There’s erudition, in the summary and critique of the main economic ideas, accompanied by smart biographical asides. Here’s a lovely example on the ‘care economy’:

‘in extolling the power of the market, Adam Smith forgot to mention the benevolence of his mother, Margaret Douglas, who raised her boy alone from birth. Smith never married and at the age of 43, as he began to write The Wealth of Nations, he moved back in with his cherished old mum, from whom he could expect his dinner every day. But her role never got a mention in his economic theory.’

That comes along with a comprehensive introduction to new economics theory and practice – a compendium of hundreds and thousands of innovators, activists and thinkers trying to incubate new thinking on money, financial systems, tax. Pretty much everything is ripe for redesign, with an urgency created by the tick tock of climate change. ‘Ours is the first generation to properly understand the damage we have been doing to our planetary household, and probably the last generation with the chance to do something about it’.

That comes along with a comprehensive introduction to new economics theory and practice – a compendium of hundreds and thousands of innovators, activists and thinkers trying to incubate new thinking on money, financial systems, tax. Pretty much everything is ripe for redesign, with an urgency created by the tick tock of climate change. ‘Ours is the first generation to properly understand the damage we have been doing to our planetary household, and probably the last generation with the chance to do something about it’.

The chapter I must enjoyed was when she comes back to growth and discusses the bicycle problem (although she never calls it that). What if growth is like a bicycle – if you stop moving forward, you fall off? If politics, society and the structure of capitalism depends on growth (for example by requiring a return on investment, or through the nature of market competition), how can they wean themselves off it and survive? She wrestles with the arguments, coming up with this memorable summary of the two camps:

‘The keep-on-flying passengers: economic growth is necessary – and so it must be possible

The prepare-for-landing passengers: economic growth is no longer possible – and so it cannot be necessary’.

Although she claims to be agnostic, her sympathies clearly lie with the second camp, and the chapter sets out some fascinating ideas – rethinking the nature of money, reforming finance, changing the nature of taxation, new metrics – for how society needs to ‘prepare for landing’. That seems like a thoroughly original and brilliant way to get past the insane optimism of the exponentionalists, and the sloppy oppositionalism of the degrowthers.

Wonderful, but what influence will the book have? Because in some ways Doughnut Economics is an example (albeit a particularly brilliant one) of what I call IIRTW (‘If I Ruled the World’) thinking. There’s a cursory nod to the nature of power, but the implicit theory of change seems to be to invoke a sort of progressive/environmentalist version of Silicon Valley – a movement of smart, dedicated people building a New Jerusalem. Their brilliance will identify the win-win solutions, while some ill defined political upsurge will overcome the blockers. Together they will save the world.

What’s missing is a decent power analysis and discussion of how the ideas interact with politics (beyond broad social movement activism): not just the power of bad guys, but the workings of democracy. When I discussed this issue with Tim Jackson, another environmental economist guru, he ended up accepting that autocratic systems were probably the most likely to implement his ideas.

But great ideas, and brilliant framing, still make change – and this book is a classic combination of both. If only 10% of the ideas get implemented, the world will be a much better place. And I’m always happy to help if Kate wants to write a follow up – Doughnut Politics anyone?

Here’s Kate summarizing her message on Open Democracy. And in keeping with her commitment to visuals, check out these brilliant animations of the book’s main ideas. Here’s the first, setting out her stall on GDP

Plus a 90 second trailer for the book

April 4, 2017

Building State Capability: Review of an important (and practical) new book

Jetlag is a book reviewer’s best friend. In the bleary small hours in NZ and now Australia, I have been catching up on my reading. The latest was ‘Building  State Capability’, by Matt Andrews, Lant Pritchett and Michael Woolcock, which builds brilliantly on Matt’s 2013 book and the subsequent work of all 3 authors in trying to find practical ways to help reform state systems in dozens of developing countries (see the BSC website for more). Building State Capability is published by OUP, who agreed to make it available as an Open Access pdf, in part because of the good results with How Change Happens (so you all owe me….).

State Capability’, by Matt Andrews, Lant Pritchett and Michael Woolcock, which builds brilliantly on Matt’s 2013 book and the subsequent work of all 3 authors in trying to find practical ways to help reform state systems in dozens of developing countries (see the BSC website for more). Building State Capability is published by OUP, who agreed to make it available as an Open Access pdf, in part because of the good results with How Change Happens (so you all owe me….).

But jetlag was also poor preparation for the first half of this book, which after a promising start, rapidly gets bogged down in some extraordinarily dense academese. I nearly gave up during the particularly impenetrable chapter 4: sample ‘We are defining capability relative to normative objectives. This is not a reprisal of the “functionalist” approach, in which an organization’s capability would be defined relative to the function it actually served in the overall system.’ Try reading that on two hours’ sleep.

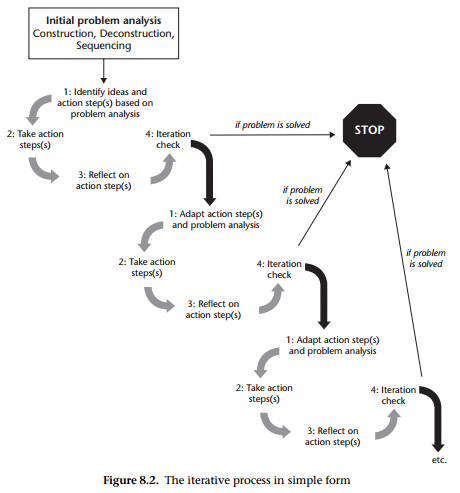

Luckily I stuck with it, because the second half of the book is an excellent (and much more accessible) manual on how to do Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation – the approach to institutional reform that lies at the heart of the BSC programme.

Part II starts with an analogy that then runs through the rest of the book. Imagine you want to go from St Louis to Los Angeles. How would you plan your journey? In modern America, it’s easy – car, map, driver and away you go. Now imagine it is 1804, no roads and the West had not even been fully explored. The task is the same (travel from East to West), but the plan would have to be totally different – parties of explorers going out seeking routes, periodic time outs to decide on the next stage, doing deals with native American leaders along the way, and constantly needing to send back for more money and equipment. Welcome to institutional reform processes in the real world. The trouble is, say the authors, too many would-be reformers are applying 2015 approaches to the 1804 world – in lieu of a map, they grab some best practice from one country and try to ‘roll it out’ in another. Not surprisingly, it seldom works – many country political systems look more like 1804 than 2015.

The chapter that really got me excited was the one on the importance of problems. ‘Focussing relentlessly on solving a specific, attention-grabbing problem’ has numerous advantages over ‘best practice’, solution-driven cookie cutters:

The chapter that really got me excited was the one on the importance of problems. ‘Focussing relentlessly on solving a specific, attention-grabbing problem’ has numerous advantages over ‘best practice’, solution-driven cookie cutters:

Problems are often context specific and require you to pay sustained attention to real life, rather than toolkits

You can acknowledge the problem without pretending you have the solution – that comes through experimentation and will be different in each context

Exploring and winning recognition of the problem helps build the coalition of players you need to make change happen

Problems often become clear during a shock or critical juncture – just when windows of opportunity for change are likely to open up

The book offers great tips on how to dig into a problem and get to its most useful core – often people start off with a problem that is really just the absence of a solution (eg ‘we don’t have an anti-corruption commission’). The trick is to keep saying ‘why does this matter’ until you get to something specific that is a ‘real performance deficiency’. Then you can start to rally support for doing something about it.

The next stage is to break down the big problem into lots of small, more soluble ones. For each of these, the book recommends establishing the state of the ‘change space’ for reform, born of a set of factors they label the ‘triple A’: Authority (do the right people want things to change?), Acceptance (will those affected accept the reform?) and Ability (are the time, money and skills in place?). Where the 3 As are present, then the book recommends going for it, trying to get some quick wins to build momentum. Where they are not, then reformers face a long game to build the change space, before jumping into reform efforts.

In all this what is special is that the advice and ideas are born of actually trying to do this stuff in dozens of countries. The authorial combination of Harvard and the World Bank means governments are regularly beating a path to their door, as are students (BSC runs a popular – and free – online learning course on PDIA).

Another attractive feature is the effort to avoid this becoming some kind of kumbaya, let a hundred flowers bloom justification for people doing anything  they fancy. To give comfort to bosses and funders, they propose a ‘searchframe’ to replace the much-denounced logframe. This establishes a firm and rapid timetable of ‘iteration check-ins’ where progress is assessed and new ideas or tweaks to the existing ones are introduced.

they fancy. To give comfort to bosses and funders, they propose a ‘searchframe’ to replace the much-denounced logframe. This establishes a firm and rapid timetable of ‘iteration check-ins’ where progress is assessed and new ideas or tweaks to the existing ones are introduced.

Finally a chapter on ‘Managing your Authorizing Environment’ is a great effort at showing reformers how to do an internal power analysis within their organizations, and come up with an internal theory of change on how to build and maintain support for reforms.

That chapter got me thinking about the book’s relevance to INGOs. It is explicitly aimed elsewhere – at reforming state systems, but people in NGOs, who often work at a smaller scale than the big reform processes discussed in the book, could learn a lot, particularly from the chapters on problem definition and the authorizing environment. Oxfam has been going through a painful and drawn out process to integrate the work of 20 different Oxfam affiliates, known as ‘Oxfam 2020’. I wonder what would have happened if we had signed up the 3 PDIA kings to advise on how to run it?

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers