Duncan Green's Blog, page 124

February 20, 2017

Being bold: what Oxfam’s campaign on Yemen can teach us all about change

In recent years, one of the things that has made me really proud to work for Oxfam has been its stand on Yemen. Here, Maya Mailer (@mayamailer) distils the lessons from our campaign.

How do you convince people to care about a place no one has heard of? When we first started our campaign on Yemen almost two years ago, it wasn’t simply a ‘forgotten crisis’. As one of my media colleagues said to me at the time, a crisis needs to be known first before it can be forgotten. Polling in the UK proved almost impossible: people didn’t understand the question because they didn’t know where Yemen was. And in any case, the terrible war in Syria and refugee flows dominated media headlines. There just wasn’t room for another Middle Eastern war.

How do you convince people to care about a place no one has heard of? When we first started our campaign on Yemen almost two years ago, it wasn’t simply a ‘forgotten crisis’. As one of my media colleagues said to me at the time, a crisis needs to be known first before it can be forgotten. Polling in the UK proved almost impossible: people didn’t understand the question because they didn’t know where Yemen was. And in any case, the terrible war in Syria and refugee flows dominated media headlines. There just wasn’t room for another Middle Eastern war.

How to turn that around? Our campaign on Yemen has highlighted the catastrophic humanitarian crisis and the urgent need for a ceasefire. It has sought to give a platform to Yemeni civil society and described how Yemeni women are striving for peace.

The most controversial aspect has been our campaign calling on the UK and US governments to suspend their arms

October 2016: Ahead of a UK parliamentary Debate on Yemen, Oxfam campaigners pose as Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson. Photo: Andy Hall

sales to Saudi Arabia. It helped move Yemen from a fringe concern to a humanitarian and political issue that cannot be so easily ignored. The way we did this holds lessons for all of us who care about change.

But first, here’s the potted background: in March 2015, the conflict in Yemen escalated when a Saudi led military coalition intervened after the Houthi rebel movement ousted the country’s President. The war in Yemen has been brutal and deadly – all sides have committed atrocities. The Saudi coalition, relying on British and American-made bombs, has hit schools, hospitals, mosques, homes and mourners at funerals. The ground fighting has also been indiscriminate. Yemen was already the poorest country in the Middle East, and the conflict and a de facto blockade have brought it to the brink of famine. During this time, the UK government alone has approved arms sales to the tune of 3.3 billion pounds to Saudi Arabia.

We knew that by challenging vast and lucrative arms sales, we would be butting up against powerful geo-political and business interests. But a small group of us felt we had to go for it.

There were three main reasons:

Precisely because governments that we had a degree of influence over were so complicit in the crisis, we had an exceptional opportunity to reduce the suffering in Yemen.

Oxfam had been in Yemen for 30 years. We have a strong programme on the ground and we were one of the first NGOs to scale up operations in response to the intensifying conflict.

Oxfam had campaigned for ten years for an Arms Trade Treaty which was designed to prevent the carnage caused by just these kinds of arms transfers.

So on our side, we had both legitimacy from our on-the-ground presence and moral clarity. We had a clear call

Aden

that stirred passions and could be easily understood. People get the connection between arms sales and suffering.

But calling out the Saudi coalition and its backers posed security and funding risks for Oxfam. I was involved in many difficult conversations as to whether we could afford to take on this level of risk.

We did so because ultimately even reticent colleagues were won over by both the moral and pragmatic argument: the best and probably the only way to get desperately needed attention to the humanitarian crisis in Yemen was to focus on the scandal of arms sales. We also had leadership from the top, with our CEO Mark Goldring, quickly getting behind the campaign, which was crucial in giving us the confidence to be bold.

This hasn’t been a straight-forward linear process. We’ve had to dial our campaigning up and down, depending on the risks to our programme. But throughout, we’ve had trust between a small core group of campaigner, media and programme colleagues. A clear goal has meant that our planning meetings have focused on action and opportunities. We haven’t consumed energy on introspective strategy sessions. There has been space to be creative and responsive.

It all began with TV. We had our first breakthrough in the UK back in September 2015, when Oxfam, after weeks of painstaking work, facilitated a visit of BBC’s Newsnight to Yemen. Eventually, more of the big TV broadcasters made it into the country, including Channel Four and BBC News (here and here). It was only when the shocking images started coming out of Yemen that it pierced the public consciousness. That made it possible to launch the Yemen  DEC appeal.

DEC appeal.

I’ve always been a big believer in the power of the images and this experience has reinforced that belief. The day before that first 2015 BBC Newsnight piece, I’d sparred with a campaigns colleague who told me that there was no point investing in campaigning in Yemen because we could never get ‘cut through’. I threw arguments at him, but he wouldn’t budge. He texted me the next evening, the minute after the Newsnight piece ended, to say we had to do more to relay what was happening. Sometimes it is only a human story unfolding before your eyes that will move you in the heart, rather than in the head.

So we got media coverage combined with excellent reports from Amnesty and Human Rights Watch. And yet as we all know, evidence isn’t enough to bring about change. When you’re up against vested interests, you need allies on the inside and you need to recognise that the power bloc you are seeking to influence is not necessarily homogenous. Oxfam, with others, has worked hard to cultivate unusual establishment allies and to mobilise unusual suspects to speak out.

So where are we now?

Shortly before leaving office, against all the odds, the Obama administration suspended a major arms deal to Saudi Arabia because of concerns over targeting practices in Yemen. In the UK, Yemen has gone from being a concern of a handful of MPs to a controversial and mainstream political issue. A cross-party parliamentary committee has said that UK arms sales must stop, pending an investigation. The government faces a judicial review. Journalists and broadcasters who told me they just couldn’t run the story are now regularly reporting on Yemen. The DEC appeal raised £17 million from the British public for a crisis that was virtually unknown a few months previously.

This is a huge change from where we were. It is easy to think that of course such a staggering humanitarian crisis should have (at least some) media exposure and that of course governments fuelling the crisis should have their feet held to the fire. But none of us believed this would be possible when we started out.

So let’s recap the main ingredients that helped get us here:

Moral clarity

Legitimacy from our programmes

Trust among the core group driving change + leadership from the top

Space for creativity and speed

Powerful images and human stories

Unusual methods and establishment allies.

But so far, there is little cause for celebration. The Trump administration has revoked the arms sale suspension. UK arms sales continue as the government digs in its heels.

And worst of all, the people of Yemen continue to suffer. This type of change is always going to be two steps forward and one step back. Perseverance is all. It’s a long hard fight – and that fight, for Yemen, and for the international norms we all hold dear, has never been more important.

February 19, 2017

Links I Liked

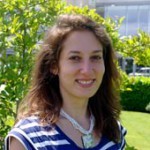

Forget the headlines. American attitudes toward Muslims have improved over the last 3 years via Ranil Dissayanake

Interest in a Universal Basic Income is growing. The World Bank’s Shanta Devarajan sets out the case and Todd Moss asks ‘What Would Mahatma Gandhi Do?’ over the UBI debate in India

Good to see other aid donors mobilizing in response to the US restoring the ‘Global Gag Rule’. Eight countries will replace the abortion funding that is lost, with a ‘She Decides’ pledging conference on 2 March, while UK Development Minister Priti Patel has announced a family planning funding summit, probably in July.

‘We – the world’s elite – distanced ourselves from our compatriots and lost their trust’. Dani Rodrik sympathizes with Theresa May on the folly of being a ‘global citizen’

One for your RSS feeds/email subscriptions: the new ‘Governance Soapbox’ blog by Graham Teskey and LaviniaTyrrel. “If Duncan Green can do one then so can we.” Bring it on.

‘Bad news usually happens all at once; good news happens slowly’. Nice 4 minute video summary and response to the annual Gates letter from John Green

Dear Donald Trump, put America First, but put us second … a nice satirical Valentine’s Day pitch, this time for India h/t Sony Kapoor

February 16, 2017

Shaping the future of work in a digital world – why should development organisations care?

On 13th March,

IDS

together with the

Web Foundation

and

Nesta

, are hosting the inaugural

Digital Development

On 13th March,

IDS

together with the

Web Foundation

and

Nesta

, are hosting the inaugural

Digital Development

Summit

, with the support of

DFID

and the

DFID-ESRC Impact Initiative

(FYI: I will be one of the final panel speakers). This blog post is the first in a series that will be published by organisers and participants over the coming weeks. Here IDS’s Becky Faith and Ben Ramalingam explain why the future of work in a digital age matters for development actors, and what we need to be thinking and doing differently. (As Becky and Ben note, I posted on this topic back in December – see

here

.) Plus you get to vote at the end.

Summit

, with the support of

DFID

and the

DFID-ESRC Impact Initiative

(FYI: I will be one of the final panel speakers). This blog post is the first in a series that will be published by organisers and participants over the coming weeks. Here IDS’s Becky Faith and Ben Ramalingam explain why the future of work in a digital age matters for development actors, and what we need to be thinking and doing differently. (As Becky and Ben note, I posted on this topic back in December – see

here

.) Plus you get to vote at the end.

In recent months, it’s been hard to avoid breathless headlines warning of the impact of technology and digitisation on the world of work. While the tone of these accounts varies from the enthusiastic to the doom-laden, there is agreement that significant and urgent changes are needed at many levels including;

how businesses create and sustain jobs,

how governments enable and support decent work,

the choices available to people in their working lives.

There are two big reasons why this should matter for development organisations.

First, every major report highlights the fact that developing countries are likely to be hit harder by digitisation and automation than the US and Europe. Data from the World Bank analysed by the Oxford Martin School and CitiBank shows that susceptibility to automation is negatively correlated with GDP per capita – the poorer the country, the more vulnerable it is.

Research by the Oxford Martin School also shows that some 85% of jobs in Ethiopia and similarly high shares of the workforce in countries such as China and Nigeria are susceptible to automation.

Second, much of the debate on the future of jobs has focussed on the formal sector, with little attention paid to the 2 billion working age adults classified as being outside of the workforce. 82% of South Asians, 66$% of Sub Saharan Africans, 65% of people in East and Southeast Asia, and 51% of people in Latin America work in the informal economy, yet relatively little attention has been paid to how automation affects their livelihoods.

Despite the urgency of this issue, many governments and global institutions seem ill prepared for the impending impacts. Labour market policies and education and training systems in most countries are simply not prepared for large-scale, rapid changes such as those that could arise from large-scale digitisation. And policy makers are not putting in place anticipatory and adaptive measures at the scale necessary to cope with the impact of digital shocks and stresses.

This gap in thinking and action is especially noticeable among the international development community. With a few exceptions, including research supported by the DFID-ESRC Impact Initiative that will be showcased at the Summit, this issue has as yet received little attention in research, policy or practice.

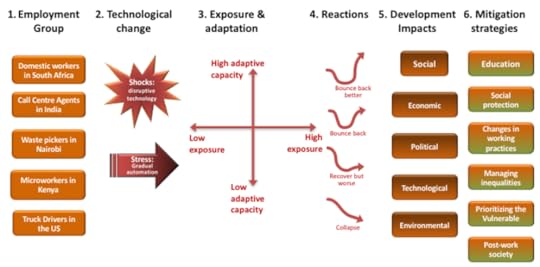

At IDS, we have spent time thinking through the implications of digital technologies on different groups, and have developed an emerging framework we are calling ‘workforce resilience’. This is shown in preliminary form in Diagram 1, and we will be expanding and building upon it at the Summit.

Diagram 1: Exploring workforce resilience

For now, suffice to say that we believe the development community needs to urgently and collectively think about:

the kinds of people who might be most at risk (including the illustrative groups in diagram 1)

the shocks and stresses that they might be subject to

their exposure and adaptive capacity (which will vary within and across groups)

the trajectories their livelihoods might take

the developmental impacts (social through to environmental)

the possible mitigation strategies

On this last point, it is becoming ever more apparent that we need to think about the appropriate mix of policy interventions that can capitalise on positive possibilities while mitigating the negative impacts. Current ideas range from enhanced social protection measures, such as Universal Basic Income, to STEM (science, technology, engineering and maths) skills building for women and children, through to employment schemes and shifts in working patterns.

This evolving array of responses requires creativity and foresight, and cross-institutional approaches: neither markets, states nor civil society actors alone can do the job. There are going to be roles for everyone from Silicon Valley technologists to donors, philanthropists, NGOs, trade unions and researchers if we are to fully to engage with these challenges. Which is precisely why we and our partners are focusing the 2017 Digital Development Summit next month on the Future of Work. This will be an opportunity to collectively envision and determine ways in which technology might be used to reduce wealth inequalities and accelerate sustainable livelihoods.

Through a series of blogs over the coming weeks and a Briefing Paper that will be disseminated ahead of the Summit, we aim to start an evidence-based, focused and broad debate on this emerging global challenge. We will be drawing on ESRC/DFID funded research to ground discussions on impact of digitisation in people’s lives and capabilities; looking at a broad range of impacts of the spread of technology from the overblown promises of the impact of broadband coverage in East Africa to the up-and-downsides of mobile ownership for young people’s work and life opportunities in South Africa. We will also be highlighting vital research and practical work on digital jobs in Africa, the gig economy in South Africa and technology use by informal workers.

What do you think? Are the threats from digitisation overblown? Or, as Duncan asked in his blog a couple of months back, is this time really different? What are the different roles for states, markets and society? And how should the development community be responding?

So please vote in the poll below and share your perspectives in the comment thread – and we will incorporate the best responses and debates into the Summit proceedings.

Note: There is a poll embedded within this post, please visit the site to participate in this post's poll.

February 15, 2017

The global state of child marriage #GirlsNotBrides

OK, it’s finally happened, I’ve woken up with nothing to post – I’ve been on the road for the last two weeks, and it’s hard to keep feeding the blog between events, travel etc. So I thought I’d just repost the most powerful item from the 60 or so articles in my RSS feed today. Shanta Devarajan setting out the case for a Universal Basic Income was a strong candidate, but in the end I went with this on child marriage, because the video made me cry. By Darejani Markozashvili on the World Bank’s People, Deliberation, Spaces blog.

Child marriage is a violation of human rights and needs to be addressed worldwide by citizens, community organizations, local, and federal government agencies, as well as international organizations and civil society groups. Child marriage cuts across borders, religions, cultures, and ethnicities and can be found all over the world. Although sometimes boys are subjected to early marriage, girls are far more likely to be married at a young age.

This is where we stand today: in developing countries, 1 in every 3 girls is married before the age of 18. And 1 in nine girls is married before turning 15. Try looking at it this way: the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) estimates that if current trends continue, worldwide, 142 million girls will be married by 2020. Another prediction from a global partnership called Girls Not Brides suggests, that if there is no reduction in child marriages, the global number of child brides will reach 1.2 billion by 2050.

Why is this such a critical issue? Child marriage undermines global effort to reduce poverty and boost shared prosperity, as it traps vulnerable individuals in a cycle of poverty. Child marriage deprives girls of educational opportunities. Often times, when girls are married at a young age, they are more likely to drop out of school and are at a higher risk of death due to early childbirth. According to the World Health Organization, complications during pregnancy and childbirth are the second cause of death for 15-19 year-old girls globally.

In order to raise awareness about child marriage in the Middle East, a Lebanon-based organization, KAFA, produced this video as a social experiment.

According to the World Policy Center, in 7 countries, there is no nationally set minimum age of marriage. An additional 5 countries have the minimum age for girls to be married at age 13 or younger. Another 30 countries allow girls to be married at age 14 or 15.

Want to find out what the minimum age is of marriage for girls with parental consent? Check out the data from the World Policy Center:

February 14, 2017

How Change Happens (or doesn’t) in the Humanitarian System

I’ve been in Stockholm this week at the invitation of ALNAP, the Active Learning Network for Accountability and  Performance in Humanitarian Action, which has been holding its annual meeting on the banks of a frozen Swedish river. I was asked to comment on the background paper for the meeting, Changing Humanitarian Action?, by ALNAP’s Paul Knox-Clarke. I read the paper on the flight over (great believer in Just in Time working practices….) with mounting excitement. It’s a brilliant, beautifully written intro to how change happens (or doesn’t) in the aid business, and to a lot of different schools of thought about change.

Performance in Humanitarian Action, which has been holding its annual meeting on the banks of a frozen Swedish river. I was asked to comment on the background paper for the meeting, Changing Humanitarian Action?, by ALNAP’s Paul Knox-Clarke. I read the paper on the flight over (great believer in Just in Time working practices….) with mounting excitement. It’s a brilliant, beautifully written intro to how change happens (or doesn’t) in the aid business, and to a lot of different schools of thought about change.

The paper starts off with the widespread frustration in the humanitarian sector. Despite dozens of new initiatives, impressive sounding statements and resolutions, and endless organizational change processes, ‘everything has changed, but nothing has changed’ in the words of one African humanitarian veteran. Changes include an avalanche of information technology, the rise of cash programming, geopolitical shifts towards new donors, growth in the number and size of humanitarian emergencies, organizations and the budgets allocated to them. Yet still people ‘did not see these ‘big’ changes as having made a real difference to the lives of people affected by crisis.’ So the paper is as much as study in how change doesn’t happen as how it does.

The bit of the paper that really grabbed me was the succinct summary of three conventional models of change that underpin humanitarian thinking, and three new ones that could shed new light. None of them are definitive; all contribute to a deeper understanding.

The three conventional models are:

Machine: the aid system is a complicated but controllable device. Change comes from learning how to identify and pull the right levers

Market: the humanitarian system is full of firms – big incumbents and scrappy insurgents – and through competition and innovation, a process of creative destruction generates steady, if painful, progress.

Political economy: humanitarian players pursue their organizational interests, aimed at self preservation and increasing their revenue and power. The rest is PR.

The three alternative models are:

The system as society: organized by politics and culture (shared meaning), rather than crude economic self interest. Power is held in many different ways and change is far more fluid and unpredictable than a political economy model would predict.

Complex sure, but is it adaptive?

The system as ecosystem: the humanitarian sphere is a typical complex adaptive system, made up of a whole series of agents each reacting to what the others do. Change is unpredictable, emergent and often discontinuous (big spikes, separated by periods of inertia). Feedback often dampens change and drags the system back to equilibrium. Not only that, but the system is ‘constantly changing without our intervention, and our efforts to change it will be more like joining a football game than sitting down to fix a broken clock.’

The system as mind: while cultural models draw on anthropology, this model draws on psychology. This bit is worth quoting at length:

‘Perhaps the most influential approach to individual and organisational change, however, has drawn on Gestalt psychology, which addresses the relationship between the world and our perception of it. Broadly, the approach suggests that human beings do not perceive the whole reality of which they are a part (‘the ground’) but unconsciously select certain elements to create a ‘figure’: an internally consistent representation of reality that is not, in fact, the sum of the elements which initially created it, but which is experienced as the whole. These figures are extremely durable, but can be changed by a process whereby the individual becomes aware of inconsistencies, and then directs energy to breaking down the existing figure and creating a new one. Because ‘human action is a self-regulating system that deals with an unstable state in such a way as to produce a state of stability’; the mind will generally resist this process, as it aims to maintain the stability of the existing figure. Resistance to change, then, should not be seen as a conscious process to subvert it, but rather as a normal and healthy process that enables the individual (or organisation) to retain stability and purpose in a chaotic world.’

This is really good stuff. Apart from being Paul’s praise singer, my comments focussed on what for me is the weakest section of the paper – the ‘so whats’. He makes a general appeal for adaptive management methods, accepting loss of control and encouraging networks and decentralized approaches and rethinking the role of leaders. Beware linear thinking, support changes that are already happening, recruit external drivers of change to shake up the system.

OK as far as it goes, but I think that falls short of really thinking through an internal theory of change. I would have liked to see:

A more considered approach to building multi-stakeholder coalitions that acquire the reservoirs of trust needed to act when a critical juncture presents itself (and the humanitarian system appears to evolve through a cycle of catastrophic failures like Rwanda, followed by heart searching and attempts at change). How to channel the next major screw-up into fundamental reform?

HR: change begins and ends with the people who are working in the system. How do we overcome the widespread anxiety and fear of failure that cripples innovation? How do we recruit and retain mavericks and risk takers? How do we support the emergence of networks of dissidents to generate new ideas and approaches that will one day become the new mainstream?

And case studies from other global networks that have overcome inertia – air traffic control? The postal service? The Vatican?

As usual when change doesn’t happen even when everyone says they want it, inertia probably comes down to a combination of ideas (eg we know best), institutions (eg short term funding cycles for emergency response) and interests (eg CEOs judged by increasing turnover). What could disrupt these forces? I can think of at least 3 (feel free to add more):

New entrants: eg startups with different approaches, or new donors doing things differently

New tech: cash programming really does seem to push power from the providers to the ‘beneficiaries’. Suddenly those affected get to decide what aid money should be spent on, and lots of humanitarians could be out of a job. It may just be the trigger for genuine change

And of course, another horrific crisis and/or humanitarian failure/scandal. Let’s hope we don’t have to wait for one of those.

Finally, I was really looking forward to sharing a platform with humanitarian rock star Jan Egeland, but he had to pull out at the last minute. In revenge, here is the genius satirical video about him by Norwegian comic musicians, Ylvis. Enjoy.

February 13, 2017

What does ‘Security’ mean? Great (and well-written) paper from IDS

I have been known in the past to be a little snippy about the writing style of esteemed colleagues  from the Institute of Development Studies. So in the interests of balance, I want to celebrate a beautifully written, lyrical paper by IDS’ Robin Luckham. Whose Security? Building Inclusive and Secure Societies in an Unequal and Insecure World (OK, they could have worked on the title) is also hugely ambitious (it summarizes the evolution of the concept of Security since the French Revolution) and very thought provoking. Which makes it very hard to do justice to it in a blog, but here are some appetite-whetters.

from the Institute of Development Studies. So in the interests of balance, I want to celebrate a beautifully written, lyrical paper by IDS’ Robin Luckham. Whose Security? Building Inclusive and Secure Societies in an Unequal and Insecure World (OK, they could have worked on the title) is also hugely ambitious (it summarizes the evolution of the concept of Security since the French Revolution) and very thought provoking. Which makes it very hard to do justice to it in a blog, but here are some appetite-whetters.

A taste of the writing from the exec sum:

‘Development researchers, governance specialists, security and international relations analysts are cartographers of the modern world. Their job is to untangle the tangled, yet in doing so they all too often make flat all that is high and rolling. This paper considers one particular piece of map-making: the interface between security and development. It tries to render visible some of the bumps, joins and turnings which lie beneath the maps.

The theory and practice of security, like that of development, issued from the historical transformations which gave rise to the post-Second World War world order. Since the end of the Cold War they have increasingly intertwined and security has been mainstreamed into

Refugee camp in DRC

development. Yet neither security nor development has fully extricated itself from the violent and extractive relationships which developed in the colonial period and continue in many respects to this day.

Contradictions lie at the heart of the security – development nexus. On the one hand, security is a process of political ordering. Even more than development, it intermeshes with established power structures, property relations and inequalities. On the other hand, it is founded upon the claim that states and other forms of public order make citizens safe from violence and insecurity. In principle, it is equally shared and socially inclusive, even if in practice it is anything but.

The vernacular understandings, day-to-day experience, resilience and agency of the people and groups who are ‘secured’ and ‘developed’ are the touchstone by which to evaluate security. Most people fall back upon their social identities – as women and men, members of families, clans, castes, ethnic groups, sects, religions and nationalities – to navigate their social worlds, to respond to insecurity and (sometimes) to organise for violence. At the same time, these identities are written into the structures of power and inequality, being deployed to establish hierarchies of citizenship and patterns of exclusion. Ensuring that security is inclusive is fraught with difficulty and must be negotiated at multiple levels.

The security–development nexus is not only historically contingent, but is also being torn apart by the gathering winds of change. Global balances of profit and power are shifting as new poles of global economic growth and political influence emerge. Powerful market forces drive the privatisation of the military and security sector, as well as feeding the markets in drugs and other illegal commodities, which create powerful incentives for political as well as criminal violence. Rapid technological changes, notably in information technologies, are transforming the worlds of war as well as work, and translate into struggles to control communication and shape political discourse. The framework of political authority is loosening, called in question by new forms of subaltern politics, not just in ‘fragile’ states, with greatly varying consequences, some violent, others more peaceful.

The body of the paper sets out a thought-provoking set of polarities in a series of tables, (very useful for teaching purposes). Here are two of them:

There is also a nod towards systems thinking and ‘working with the grain’, including this great passage on critical junctures:

There is also a nod towards systems thinking and ‘working with the grain’, including this great passage on critical junctures:

‘Too often historical opportunities opened at such critical junctures are missed. Or they are grasped by those, who happen to be in control of the means of force. Or they merely open the way to renewed cycles of violence and insecurity. Five such critical junctures seem especially worthy of attention:

Ruptures in ‘strong’ authoritarian regimes challenged by popular protests and/or armed rebellion. The key issue here tends to be who seizes the political moment and how. Outcomes have varied enormously even in the same region – like post-communist Eastern Europe or in post-Arab Spring Middle East – ranging from civil war to varieties of authoritarian restoration to viable democratic transitions.

Political transitions forged after successful armed uprisings against repressive ancien

Europe’s critical juncture?

régimes, including in some cases those previously propped up with external support (like Vietnam, Ethiopia, Eritrea and pre-genocide Rwanda). These uprisings open spaces for change, but also bring to power militarised groups, some in the Leninist mould, who tend to be resistant to democratic changes they are unable to stage-manage.

Political settlements brokered through negotiated peace agreements, which end mutually hurting stalemates (as in El Salvador, South Africa, Sierra Leone, Nepal and potentially Colombia), and create spaces for democratic politics that are hard for any one party or group to monopolise.

The creation of pockets of peace within conditions of durable disorder (like in Somalia, DRC, Haiti and South Sudan) which can eventually become starting points for democratic alternatives to violence, as in the case of Somaliland.

Shifts in political balances within existing competitive or partially competitive democratic systems (like the recent opposition electoral victories in Sri Lanka and Nigeria), which could (but may not) reinvigorate ailing democratic institutions, and help contain violence.’

Great stuff. As I said, impossible to summarize the paper adequately, but I hope this is enough to get you clicking through.

February 12, 2017

Links I Liked

We lost a giant last week. Hans Rosling made geeks look cool, proved that Swedish students are less intelligent than chimps, and made everyone who has ever lectured realize just how boring we really are. Whether you are celebrating his life, or discovering his genius for the first time, here’s a sample:

200 years, 200 countries and a massively positive story of human development, all in 4 minutes

Mashing a lazy newsman on Danish TV ‘There’s nothing to discuss. I am right and you are wrong.’

A greatest hits compilation (stay with it through to the sword swallowing)

And his work lives on in the Gapminder site that he founded ‘to dismantle misconceptions and promote a fact-based worldview’. Check it out – it’s amazing.

Meanwhile, on other issues

US presidential slot: Mr Men does the Mexican wall, while other cartoonists are also having a field day. Liked this  one on checks and balances. But Richard Reeves begs to differ. ‘Trump’s Presidency has been, so far, a brilliant political success’ and is well on course for two terms, he reckons.

one on checks and balances. But Richard Reeves begs to differ. ‘Trump’s Presidency has been, so far, a brilliant political success’ and is well on course for two terms, he reckons.

Chris Blattman has found a Hemingway app to sharpen up his writing style

Going open access has seen IDS get five times more readers for its journal

‘The world is suffering from complexity fatigue. The symptoms are a longing for simple answers and a world free of interdependencies’. Bill Below on the OECD Insights blog

February 9, 2017

A philanthropist using systems thinking to build peace

Steve Killelea is an intriguing man, an Aussie software millionaire who, in the words of his bio ‘decided to dedicate  most of his time and fortune to sustainable development and peace’. Think a more weather-beaten Bill Gates. He also (full disclosure) bought me a very nice lunch last week.

most of his time and fortune to sustainable development and peace’. Think a more weather-beaten Bill Gates. He also (full disclosure) bought me a very nice lunch last week.

In pursuit of this aim he set up the Institute for Economics and Peace in 2007. The institute dedicates itself to measuring the hard stuff – ‘developing metrics to analyse peace and to quantify its economic value.’ It puts these measurements into the public domain through four flagship annual reports:

The Economic Value of Peace: e.g. ‘The total economic impact of violence to the world economy in 2015 was estimated to be $13.6 trillion and is expressed in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms. This is equivalent to 13.3 per cent of world GDP or $1,876 PPP per annum, per person.’

The Global Terrorism Index: e.g. ‘There was a ten per cent decline from 2014 in the number of terrorism deaths in 2015 resulting in 3,389 fewer people being killed. Iraq and Nigeria together recorded 5,556 fewer deaths and 1,030 fewer attacks than in 2014. However, with a global total of 29,376 deaths, 2015 was still the second deadliest year on record.’

The Global Peace Index: The 10th edition found that ‘The historic ten-year deterioration in peace has largely been driven by the intensifying conflicts in the MENA region. Terrorism is also at an all-time high, battle deaths from conflict are at a 25 year high, and the number of refugees and displaced people are at a level not seen in sixty years. Notably, the sources for these three dynamics are intertwined and driven by a small number of countries, demonstrating the global repercussions of breakdowns in peacefulness. Many countries are at record high levels of peacefulness, while the bottom 20 countries have progressively become much less peaceful, creating increased levels of inequality in global peace.’

The Global Peace Index: The 10th edition found that ‘The historic ten-year deterioration in peace has largely been driven by the intensifying conflicts in the MENA region. Terrorism is also at an all-time high, battle deaths from conflict are at a 25 year high, and the number of refugees and displaced people are at a level not seen in sixty years. Notably, the sources for these three dynamics are intertwined and driven by a small number of countries, demonstrating the global repercussions of breakdowns in peacefulness. Many countries are at record high levels of peacefulness, while the bottom 20 countries have progressively become much less peaceful, creating increased levels of inequality in global peace.’

But the most innovative of the four is the Positive Peace report, which compares itself to the shift in health from focussing on sickness to focussing on health, broadly defined (including wellbeing). It uses a systems approach, seeking to quantify the ‘attitudes, institutions and structures that create and sustain peaceful societies.’ To do this it identifies 8 interlocking elements:

Well-functioning government

Sound business environment

Equitable distribution of resources

Acceptance of the rights of others

Good relations with neighbours

Free flow of information

High levels of human capital

Low levels of corruption

It then assesses each of these against a series of proxy indicators from public sources. For example Human Capital is measured by a combination of Secondary School enrolment (World Bank stats), Scientific Publications (World Bank again) and the Youth Development Index of the Commonwealth Secretariat.

I’m sure you could quibble with the gaps (environment/sustainability?) and the assumptions and value judgements  behind what constitutes ‘sound economics’ or ‘corruption’, but the IEP has an advisory council with some of the smartest people on measurement issues, so I assume they get thrashed out. Steve’s business background also comes out in a very World Bank-y emphasis on the instrumental (business) case for a lot of things which are really just good in themselves.

behind what constitutes ‘sound economics’ or ‘corruption’, but the IEP has an advisory council with some of the smartest people on measurement issues, so I assume they get thrashed out. Steve’s business background also comes out in a very World Bank-y emphasis on the instrumental (business) case for a lot of things which are really just good in themselves.

But what interests me is the niche the IEP is filling here. As the time series of its reports builds, so will their usefulness. Because they are backed by a philanthropist with a long term vision, they don’t have to follow fashion (eg to chase funding, or media profile). Feels like this is an excellent use of philanthropic funding. He could have gone for something more directly feelgood and tangible, but instead has chosen to engage at a more systemic/policy level. According to Steve the Terrorism Index ‘sadly has the most impact’, but the Positive Peace report is gaining momentum – he sees it as at least a five year project. Coincidentally, I’ve just come back from a seminar hosted by the Rockefeller Foundation on how to introduce systems thinking in support for market development – blog to follow.

I’d be interested in hearing from others who are more familiar with the work, or who have used the IEP reports – what are their strengths and weaknesses?

February 8, 2017

What determines whether/how an organization can learn? Interesting discussion at DFID.

I was invited along to DFID last week for a discussion on how organizations learn. There was an impressive turnout

Simple, right?

of senior civil serpents – the issue has clearly got their attention. Which is great because I came away with the impression that they (and Oxfam for that matter) have a long way to go to really become a ‘learning organization’.

So please make allowances in what follows for all the warm, cuddly areas of mutual agreement – I’m going to focus on the areas of disagreement, which are inevitably the most thought-provoking.

To mean anything, learning requires a change both in ideas and behaviours. So what were the theories of change that underpinned the approaches to learning in the room? I found it hard to pin down exactly – they seemed mostly tacit – but a lot of what I heard reminded me of the discussion at Twaweza a couple of years ago. For many present, the tacit theory of change seems to be ‘knowledge → learning → changed behaviours → changed outcomes’. Yeah right.

What we realized at Twaweza was that ‘it’s all in the arrows’. You need to unpack the assumptions and think about what needs to be in place for that theory of change to have any chance of resembling what happens in practice.

And the neat linear ‘we all want to learn from the evidence’ assumptions certainly didn’t fit with my own experience of working at DFID (e.g. phoning up ODI to say ‘we need evidence of the harmful effects of EU cotton subsidies for the meeting in 3 weeks time’ – classic policy-based evidence making). Or the senior Treasury official who stomped down Whitehall to inform us that we should never question the ‘eternal truths’ about trade, namely that ‘trade liberalization leads to more trade, and more trade leads to less poverty’. No amount of knowledge, evidence etc was going to change his mind on that one. Maybe that has all changed in the decade since I left, but I would need to be convinced (preferably by some evidence!)

For my contribution, I played around with a 2×2 – how big is the new idea/piece of learning v how well aligned (or not) is it with current thinking and practice. Some 2x2s prove very useful, others get shot down in flames by FP2P readers. Let’s see which way this one goes. (By the way, does anyone have an easy way of putting together 2x2s? Doing them in Word is a total pain).

How does learning take place in the four quadrants in an institution like DFID (Oxfam isn’t much different, I suspect)?

How does learning take place in the four quadrants in an institution like DFID (Oxfam isn’t much different, I suspect)?

Small idea, aligned with organization: this is the only quadrant that fits the implicit theory of change, provided there are mechanisms in place to disseminate the new ideas, an enabling environment (incentives, leadership) to allow people to learn and put them into practice, and people who are actually curious about the world and want to learn new stuff. And even those are pretty big ifs.

Small idea, contrary to organization: uphill work. People will mutter ‘that seems counterintuitive’, ‘it goes against my priors’ or a variety of other euphemisms for putting their fingers in their ears and singing la la la. Individuals will either give up, or seek out fellow believers and form small guerrilla networks of dissidents. Whether that network grows depends on the individuals involved, but also on a permissive environment from bosses. The good news is that as part of its increased commitment to ‘knowledge for development’, DFID seems committed to

Yoda’s in the bottom right

encouraging these kinds of ‘communities of practice’.

Big idea, aligned with organization: You’d think this would be straightforward, but it isn’t. For a start, people in different disciplines and professions will have contrasting views about how important this ‘big idea’ really is. Should it hoover up lots of management attention and resources, taking them away from their own areas, or is it some fringe hobbyhorse that should not get too much airtime? You get the picture.

Big idea, contrary to organization: Step forward Thomas Kuhn and paradigm shifts. There will be huge resistance to the big idea from those whose disciplines, careers or views of the world it threatens. There will need to be a high degree of ‘unlearning’ – battering the organization with evidence, narratives and credible voices to show that the current paradigm needs revision. Large failures and critical junctures (eg financial crises) can help dislodge fixed ideas. Then a massive exercise in experimentation, accumulating evidence and followers, probably followed by a final battle with the existing paradigm.

But maybe not in the way he means it

And as so often, the elephant in the room was power. Power (visible, hidden, invisible) determines what evidence is seen, listened to, gets traction or is dismissed. To unpack those arrows, you also need to understand the nature of power in a large institution like DFID (or Oxfam, for that matter).

It will be fascinating to see how this discussion plays out, and the stakes are high. Any organization that is serious about ‘doing development differently’, ‘adaptive management’ etc has to get those arrows in place.

I’d be interested in hearing from others at the meeting – what did I miss(represent)?

February 7, 2017

How Change Happens + 3 months: how’s it going?

It’s now 3 months since How Change Happens came out (did I mention I’d published a new book?) so I dropped in

Day 1 – it’s worn off a bit since then (but I still can’t spell narcissistic)

at the publishers, OUP, last week to take stock.

OUP took some risks with this book, notably agreeing to go Open Access from day one. That is a huge leap from the traditional publishing model of publishing only the hardback for a year, then deciding when to go into paperback. Some people, particularly cash-strapped students used to reading on screen, are likely to take the OA route, but OUP hoped the buzz around open access would generate some sales, or people would start reading the pdf, and then see enough to buy a copy.

So what happened? Turns out that Open Access doesn’t harm book sales and if anything, promotes them. So far, OUP has sold 3,500 hardbacks and Oxfam has distributed a further 1,500 of a paperback edition at events, to staff etc..

Obviously, there’s no clear counterfactual as all books are different, but OUP are pretty convinced that OA has generated more of a buzz than a simple hardback ever could. It’s certainly better than I’ve had with any of my previous books.

The Open Access numbers are also really interesting (at least to me): 5,700 downloads of the full pdf, mainly from the Oxfam site; over 2,000 book views on Oxford Scholarship Online; and 115,000 page views on Google Books, with the average visitor reading 10 pages. Somewhere in between comes the £2 kindle version – just a couple of hundred so far.

So big tick on Open Access, and props to OUP for being willing to take the risk. Glad it’s paid off so far.

The launch schedule has been pretty gruelling – at times I have felt like one of those rock bands whose only income is from selling merchandise at the gigs (see here for the LSE version, with Naila Kabeer and Hugh Cole). The discussions have been uniformly top notch (my favourite question is still from someone at the Blackwells launch in Oxford: ‘do you believe in the perfectibility of mankind?’ – still thinking about that one). My main trips over the next few months are to Australia and New Zealand (27 March to 7 April), and the US West Coast and Canada (1-12 May). If you want to organize an event, get in touch (dgreen[at]Oxfam.org.uk).

One less gruelling and very enjoyable way to tell people about the book has been through webinars (e.g. to staff at World Vision and Care). Again, get in touch if you’re interested.

But one fly in the authorial soup (so far, at least) is translations. As long as the book is only in English, its value in many countries will be greatly reduced, and limited to elite English-speakers. If you’re interested in seeing a translation, there’s a procedure to follow. OUP’s rights team handle all translation enquires. This is so they can coordinate which publisher is interested in which language. They deal with publishers rather than individual translators, so you need to get a publisher interested before contacting the OUP team at translation.rights@oup.com. More advice on translations here. If that’s too hard, there is also this ten page summary, which anyone can translate.

And the coolest thing so far has been making a podcast with my son Calum. A Texas podcast producer got in touch and asked me if I would discuss the book with a real activist (rather than the book-writing kind). No better candidate than Calum, who foments revolution and affordable housing as a community organizer at Citizens UK. It was great fun chatting to him in a BBC studio, while the host sat in a closet in Austin (I presume for sound quality reasons, rather than personal preference). Will let you know when it goes live.

In the pipeline: a MOOC (we’re advertising for a MOOCista here, application deadline 19th Feb), a Masters module, maybe an audio book and at some point, a second edition, once I can answer that question about the perfectibility of mankind…..

Any other feedback/suggestions very welcome.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers