Duncan Green's Blog, page 121

April 4, 2017

Shakespeare, the Bible, Einstein et al on Doing Development Differently

Just finishing ‘Building State Capability’, a wonderful new book from the Doing Development Differently crew. Review on its way tomorrow, but in the meantime, sit back and enjoy these wonderful epigrams, which open the book:

Then all the elders of Israel gathered together and came to Samuel at Ramah, and said to him, “Look, you are old, and your sons do not walk in your ways.

Early PDIA seminar

Now appoint us a king to judge us [and rule over us] like all the other nations.” But their demand displeased Samuel when they said, “Give us a king to judge and rule over us.” … . Samuel reported all the words of the Lord to the people who were asking him for a king … But the people refused to listen to Samuel. “No!” they said. “We want a king over us. Then we will be like all the other nations … ”

Samuel 1:8 (c. 600 BCE)

We must not make a scarecrow of the law,

Setting it up to fear the birds of prey,

And let it keep one shape, till custom make it

Their perch and not their terror.

William Shakespeare, Measure for Measure Act 2, Scene 1

Theory is when you know everything and nothing works. Practice is when everything works and nobody knows why. We have put together theory and practice: nothing is working … and nobody

Learning by failing

knows why!

Attributed to Albert Einstein

We have added much new cultural material, the value of which cannot be discounted; however, it often fits so ill with our own style or is so far removed from it that we can use it at best as a decoration and not as material to build with. It is quite understandable why we have been so mistaken in our choice. In the first place, much has to be chosen, and there has been so little to choose from.

Ki Hajar Dewantara, Indonesian educator (1935)

[W]e tend to meet any new situation by reorganizing, and a wonderful method it is for creating the illusion of progress at a mere cost of confusion, inefficiency and demoralization. Charlton Ogburn Jr., The Marauders (1959: 72) The term “implementation” understates the complexity of the task of carrying out projects that are affected by a high degree of initial ignorance and uncertainty. Here “project implementation” may often mean in fact a long voyage of discovery in the most varied domains, from technology to politics.

Albert Hirschman, Development Projects Observed (1967: 35)

If you can’t imitate him, don’t copy him.

Baseball great Yogi Berra, advising a young player who was mimicking the batting stance of famed slugger Frank Robinson

April 3, 2017

Links I liked (and a couple of stinkers)

First, the stinkers

Just when you thought the Daily Mail couldn’t sink any lower ….

How successful were the millennium development goals? This Guardian piece seems to equate correlation and causation – as far as I can see it gives no evidence whatsoever that the MDGs had anything to do with the acceleration of poverty reduction after 2000.

Next the grim, but important

Why do countries relapse into war? Analysis of 109 conflicts since 1970 finds some very thought provoking results, eg high levels of growth initially increase the likelihood of relapse, but over long term reduce it.

The World’s most homicidal cities are all in Latin America. Central America is by far the worst. Grim. h/t The Economist

The World’s most homicidal cities are all in Latin America. Central America is by far the worst. Grim. h/t The Economist

Now for the more upbeat

Man tries to burn EU flag. Flag doesn’t burn because of EU regulations on flammable materials. Deeply satisfying h/t Brian Whitaker

Chris Blattman moves on from debating chickens v cash transfers to crossing swords with Lant Pritchett on the merits of targeting poverty v supporting economic growth

If you want to hear what I’ve been up to down under, here’s me being cross examined by Kathryn Ryan, New Zealand’s very cerebral national radio interviewer

Please support my old mates (and employers) at Latin America Bureau in their crowdfunding appeal to collect and publish the voices of Latin American activists

And as I arrive in Australia, you have to admit, they have the finest avian headbangers – make sure you watch to the end. V silly, but a good antidote to the Daily Mail

March 31, 2017

20th Century policies may not be enough for 21st Century digital disruption

It’s often a good sign when you rock up at a conference and hardly know anyone there. That was my experience at a

Sango Patekile Holomisa, Minister of Labour, South Africa, opening the conference

recent, rather grandiosely-named, ‘Digital Development Summit’, hosted by IDS, Nesta and the Web Foundation, which clearly got people’s attention – the places were fully booked within a day of going live. Participants were diverse: developing country ministers, donor officials, tech company execs, AI pioneers, and civil society types like me.

The topic was ‘the future of work in the digital age’ (see the IDS background paper for more details), and I got to listen to a day of presentations, taking in both the substance and the mood of the discussion. This topic, more than most others, attracts both tiggers and eeyores (for Winnie the Pooh fans – optimists and pessimists, if you’re not). The tiggers bounce around telling stories of amazing start-ups in African slums, or how drones are about to start delivering aid; the eeyores sigh and say ‘every driver in America is about to lose their job to driverless vehicles, and developing country jobs are even more at risk’. Both were represented in roughly equal numbers (and some people seemed to move from one to the other at a startling rate).  Who’s right?

Who’s right?

The pessimists have to show why this time is different – people have been predicting the end of jobs since the Luddites, and yet new sectors and jobs have emerged as fast or faster than those being destroyed. The most cogent argument was that automation, artificial intelligence and ubiquitous algorithms are different because so many sectors are being simultaneously affected, and because the pace of job destruction is outstripping the pace of skills upgrading.

The optimists, on the other hand, have to show that their technologically-driven visions can address some of the fundamental divides that we know are being deepened by the digital revolution. And there is also a need to address the fact that developing countries are most prone to the impacts of automation, and least able to build resilience to shocks and stresses.

I got my favourite task – randomly reacting on the final panel of the day to what we had heard from the actual experts. Here’s a potted summary of what I said:

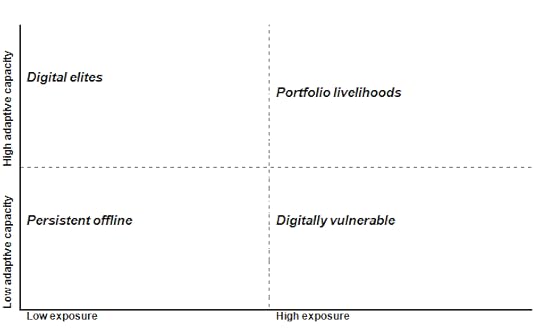

Reducing vulnerability versus enhancing agency: The opening speakers talked about the need to keep people’s agency at the centre of the debate. There was a great exercise (which I missed, but which participants raved about) which used ideas from human-centred design and scenario thinking to get participants to think about how different kinds of jobs might be affected by technology, using this 2×2 matrix.

While it’s clearly not an either-or, the discussions tended to focus on reducing vulnerabilities, rather than enhancing adaptive capacities. Having identified different groups of workers who would be most (negatively) affected by technology, the debate was on what could be done to reduce exposure through measures like social protection, education, and so on. There were also some ideas generated about enhancing adaptive capacity through digital technologies: for example, how digital tools could be used to enhance collective action and bargaining for digital jobs; or used to expand access to education opportunities. But these seemed to be in the minority.

What’s the critical juncture? While there is no unanimous agreement on whether robots and AI will destroy or create jobs overall, what is clear is that the current wave of technologies – from mobile phones to uberisation of the marketplace – is contributing to falling wages, living standards and job security. Do we need some kind of global wake-up call to take account of this hidden reality? I suggested that this we need a digital equivalent of the 2008 financial crisis in order to see the real impacts and trigger genuine policy engagement and change. Until then the discussions about regulation – whether voluntary, soft or hard – will remain largely theoretical.

Compensate digital ‘losers’ from the profits of digital ‘winners’: there are many ways of thinking about this, see my previous post, but most would involve some kind of taxation and compensation. Along with my suggestion for digital transaction taxes, robot taxes got a lot of air time, as did novel approaches to social protection such as Universal Basic Income.

20th century solutions for 21st century problems? But if even half of the predictions of the eeyores are correct, these kinds of measures hardly feel up to the seismic challenges under way. What is the point in circling the wagons around shrinking pockets of paid, non-automatable jobs, if they are all destined for the scrapheap in the end? It may be that something far deeper is changing, such as a definitive sundering of the links between consumers and producers (previously both people, now a world with many human consumers but very few human producers).

20th century solutions for 21st century problems? But if even half of the predictions of the eeyores are correct, these kinds of measures hardly feel up to the seismic challenges under way. What is the point in circling the wagons around shrinking pockets of paid, non-automatable jobs, if they are all destined for the scrapheap in the end? It may be that something far deeper is changing, such as a definitive sundering of the links between consumers and producers (previously both people, now a world with many human consumers but very few human producers).

Much of the discussion of this new and emerging challenge seemed to be based on 20th century ideas of social, government and corporate policy – social protection, education, taxation, regulation and so on.

But we could be facing a tipping point, the moment that will finally overwhelm the fraying edifice of traditional economics, opening the way for a return to a ‘moral economy’ based on broader understanding of ‘value’, which includes culture, leisure and care at its centre, rather than as an afterthought. After all, even if robots pick the kids up from school, aspects of the care economy are likely to persist, and could well end up at the heart of a post-automation division of labour. We do the loving, the singing and the sport, while the robots get on with the making. Sounds good to me (but then you haven’t heard me sing).

March 30, 2017

So is ‘Doing Development Differently’ a movement now? And if so, where’s it going?

Guest post by Graham Teskey,

Principal Global Lead for Governance, Abt JTA, Australia and all round aid guru

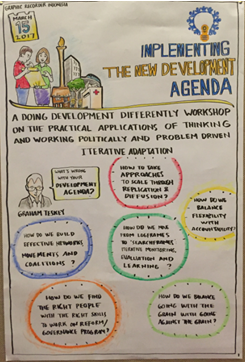

The fourth meeting of the ‘Doing Development Differently’ movement (as one of its founders, Michael Woolcock, calls it) was held over two days in Jakarta a couple of weeks ago. Jointly hosted by the Government of Indonesia, the World Bank and Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, the workshop attracted over 200 participants from south-east Asia, the Government of Indonesia, donors, civil society and the private sector. We were also joined by a bunch of highly skilled artistes (see the cartoons!).

Over the last twelve months or so, one of the questions facing the cheerleaders of DDD, and its sister ‘movement’, the International Community of Practice on Thinking and Working Politically, has been whether to deepen knowledge of the agenda, or broaden its appeal and support. The workshop in Jakarta was designed to do both, delving into some specific issues that practitioners are grappling with. These were:

Over the last twelve months or so, one of the questions facing the cheerleaders of DDD, and its sister ‘movement’, the International Community of Practice on Thinking and Working Politically, has been whether to deepen knowledge of the agenda, or broaden its appeal and support. The workshop in Jakarta was designed to do both, delving into some specific issues that practitioners are grappling with. These were:

Taking DDD approaches to scale through replication and diffusion;

From ‘logframe’ to ‘search-frame’: iterative monitoring and learning;

Networks, movements and coalitions: beyond the usual suspects;

Flexible and accountable: making your authorising environment work for you;

Building the dream team: politically astute, problem driven and adaptive; and

Going against the grain: gender and inclusion.

I don’t know whether it was the sheer size of the gathering, the great food or the videos, but there was a real buzz about this event. It is clear that if nothing else, the language of DDD and TWP definitely strikes a chord across a diversity of development professionals. In the quieter moments of the event (there were few) I pondered why this should be. Is it because we all want to keep up with Harvard professors? Or we all want to be associated with the Next Big Thing?

I think it is pretty clear that something more fundamental is at play. And that is that development practitioners are, at one and the same time:

Committed to learning from experience;

Keen to improve their own program effectiveness;

Cognisant of the political maelstrom in which they all work;

Fed up with pretending that technical ‘solutions’ alone will lead to success’, and the seeming straight jacket of the project framework.

DDD and TWP are the first ‘formal’ practitioner-based movements (or whatever we want to call them) that start from these realities. Many of the participants in Jakarta were sublimely unaware of the Harvard Manifesto or Bill Easterly’s call for ‘searchers not planners’ or the existence of the TWP CoP. But they were aware of this change sweeping over the development profession. No let me re-phrase that. Trickling over the development profession.

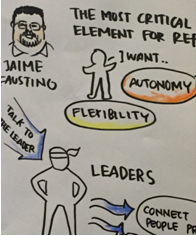

In Jakarta it was clear that two features of DDD / TWP seemed to have captured the collective imagination more than any others: first, the focus on the problem, and second, flexibility in implementation (being able to revise program design and shift budgets). By contrast, the ‘TWP approach’ of directly engaging with, and seeking to influence, the right-hand assumptions column of the project framework (previously often something akin to: “if we achieve our outputs, then assuming there is political will, we will achieve our outcomes”) gets much less attention. Why is this? Is it too hard? Too risky? Too unknowable? Or is it just too challenging for donors explicitly to align themselves with a cause? It seems we have few examples of successful practice here – the Coalitions for Change program in the Philippines is one, led by Jaime Faustino of The Asia Foundation. This is him in full flow – on the right. He really does look like that too.

the focus on the problem, and second, flexibility in implementation (being able to revise program design and shift budgets). By contrast, the ‘TWP approach’ of directly engaging with, and seeking to influence, the right-hand assumptions column of the project framework (previously often something akin to: “if we achieve our outputs, then assuming there is political will, we will achieve our outcomes”) gets much less attention. Why is this? Is it too hard? Too risky? Too unknowable? Or is it just too challenging for donors explicitly to align themselves with a cause? It seems we have few examples of successful practice here – the Coalitions for Change program in the Philippines is one, led by Jaime Faustino of The Asia Foundation. This is him in full flow – on the right. He really does look like that too.

It was interesting too that in Jakarta some presentations were not, strictly speaking, DDD or TWP. A number of activities and initiatives were badged as DDD, but really were no more than examples of good, solid professional development practice (based on data, designed and managed with extensive citizen participation, real time monitoring). They were DDP (Doing Development Properly), not DDD. This is not a problem – in some ways it is flattering – but it runs the risk of diluting the core features of DDD / TWP.

A big, ugly, practical question for many officials from donor organisations was – and is – the seeming challenge of balancing flexibility with accountability: how can I be accountable for results when I am building in flexibility in budgets, time-scales and even designs? (At this point I am reminded of a great comment by my friend and ex-colleague Verena Fritz at the World Bank, who at an earlier meeting on DDD noted that the Bank has absolutely no problem whatsoever with flexibility and adaptation of its program designs – “as long as they coincide with the mid-term review”. Bravo!)

My suggested answer to this is the difference between the line of sight of accountability and the line of sight of results.

In this diagram, the line of sight of accountability is the lower arrow. We (practitioners, aid organisations) are accountable for problem identification and investment selection – including the initial theorisation of how change happens, the quality of the our political economy analysis, the quality of design, implementation and monitoring, tracking the delivery of outputs and the extent to which outcomes are likely – i.e. a reassessment of the theory of change, and the flexible, adaptive and responsive nature of the changes put in place as a result of progress and associated learning. Donors are thus accountable up to and including the theory of change they are working to. By contrast, the results line of sight, the upper arrow, refers to the way in which outputs are expected to be translated into outcomes and goal achievement. This is why the initiative is being funded, but it is not synonymous with the donors’ line of accountability.

In this diagram, the line of sight of accountability is the lower arrow. We (practitioners, aid organisations) are accountable for problem identification and investment selection – including the initial theorisation of how change happens, the quality of the our political economy analysis, the quality of design, implementation and monitoring, tracking the delivery of outputs and the extent to which outcomes are likely – i.e. a reassessment of the theory of change, and the flexible, adaptive and responsive nature of the changes put in place as a result of progress and associated learning. Donors are thus accountable up to and including the theory of change they are working to. By contrast, the results line of sight, the upper arrow, refers to the way in which outputs are expected to be translated into outcomes and goal achievement. This is why the initiative is being funded, but it is not synonymous with the donors’ line of accountability.

So where does DDD4 leave us? Onwards and upwards I guess. The movement is gaining strength, there are an increasing number of initiatives practicing DDD and we are slowly learning from them. Overall the sense is that at last development is embracing the world of real politik; where stuff may happen at any time to throw initiatives off-course. Big challenges remain. Three for me stand out.

First is how to apply the ideas of DDD to the large-scale implementation of nation-wide programs: which bits of DDD (if any) are relevant? Sure – agree on the problem first – but beyond that? Should experimentation not precede ‘roll-out’? Are ministries of finance not leary about endorsing flaky spending commitments? Can nationwide programs such as, say, classroom construction be subject to constant review, reflection and redesign? Does this mean the relevance of DDD is circumscribed in some way – and if so just what are the boundaries?

Second, much of the growing experience has yet to be written up. The DFAT (Australian)-funded KOMPAK program in Indonesia has lots of DDD / TWP lessons, but staff have not yet had the time to write them up and synthesise them. This is about to change……

And third, DDD / TWP approaches are more staff intensive and skill intensive than what are sometimes horribly (but accurately) called ‘set and forget’ programs: staff are required that can read the vagaries of the domestic political economy in real time and respond appropriately. To do this requires technical depth, political skills and deep experience. Most donors are moving in the opposite direction: fewer, large scale programs to secure ‘efficiency savings’ are the order of the day. Deep skills are being scorned in favour of the generalist. In short, the ‘donor world’ authorising environment is increasingly hard to find.

Answers on a post card please. Well, on this blog site anyway.

March 29, 2017

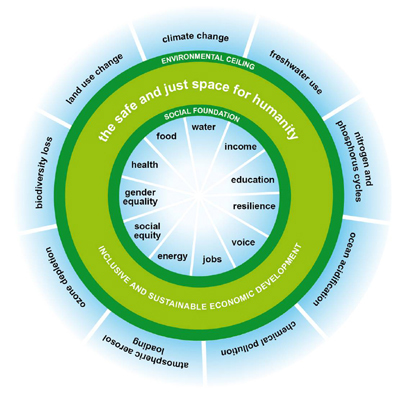

Doughnut Economics is published next week. Here’s why you should be excited

Kate Raworth’s book, Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist is published next  Thursday. I loved it , and I’ll review it properly then, but here are three excerpts to whet your appetite:

Thursday. I loved it , and I’ll review it properly then, but here are three excerpts to whet your appetite:

On the importance of diagrams:

‘Think, then, of the circles, parabolas, lines and curves that make up the core diagrams in economics – those seemingly innocuous pictures depicting what the economy is, how it moves, and what it is for. Never underestimate the power of such images: what we draw determines what we can and cannot see, what we notice and what we ignore, and so shapes all that follows. The images that we draw to describe the economy invoke the timeless truths of Euclid’s maths and Newton’s physics in their geometric simplicity. But in doing so, they slip swiftly into the back of our head, wordlessly whispering the deepest assumptions of economic theory that need never be put into words because they have been inscribed in the mind’s eye. They present a very partial picture of the economy, smoothing over economic theory’s own peculiar blind spots, enticing us to search for laws within their lines, and sending us in pursuit of false goals. What’s more, those images linger, like graffiti on the mind, long after the words have faded; they become stowaway intellectual baggage, lodged in your visual cortex without you even realising it is there.

And – just like graffiti – it is very hard to remove. So if a picture is worth a thousand words then, in economics at least, we should pay a great deal more attention to the pictures that we teach, draw and learn.’

On the true story of Monopoly (the board game, not the economic practice):

‘Fascinatingly, however, the game was originally called ‘The Landlord’s Game’ and was designed precisely to reveal the injustice arising out of such concentrated property ownership, not to celebrate it.

The game’s inventor Elizabeth Magie, when she first created her game in 1903, gave it two very different sets of rules to be played in turn. Under the ‘Prosperity’ set of rules, every player gained each time someone acquired a new property (echoing calls for a land value tax), and the game was won (by all) when the player who had started out with the least money had doubled it. Under the second, ‘Monopolist’ set of rules, players gained by charging rent to those who were unfortunate enough to land on their properties – and whoever managed to bankrupt the rest was the sole winner. The purpose of the dual sets of rules, said Magie, was for players to experience a ‘practical demonstration of the present system of land grabbing with all its usual outcomes and consequences’ and so understand how different approaches to property ownership can lead to vastly different social outcomes. ‘It might well have been called “The Game of Life”’, remarked Magie, ‘as it contains all the elements of success and failure in the real world.’ But when the games manufacturer Parker Brothers bought the patent for The Landlord’s Game from Magie in the 1930s, they relaunched it simply as Monopoly, and provided the eager public with just one set of rules: those that celebrate the triumph of one over all.’ On the state of Economics:

On the state of Economics:

‘Many of the most exciting insights driving new economic thinking seem to be emerging from every quarter but economics departments themselves. There are of course some important exceptions to that, but they are too rare. So many of the transformative ideas are originating in other fields of thought such as psychology, ecology, physics, history, Earth-system science, geography, architecture, sociology, and complexity science. Economic theory would be wise to embrace what these other perspectives have to offer. In the dance of the intellects, it is time for economics to step back from soloing in the limelight and join the troupe instead. Less Lord of the Dance and more maypole dance, more actively interweaving its theories with insights arising in other disciplines.’

March 28, 2017

Links I Liked

Update on How Change Happens. It’s now available as an audio book. I’m launching it in New Zealand and Australia over the next two weeks – see here for dates in Auckland, Wellington, Sydney, Canberra and Melbourne. Heading for Los Angeles and San Francisco first week of May – let me know if you are interested in organizing book launches there. Then I’m done….. (Advance warning: jetlag and wall to wall powerpoint may interfere with the flow of blogposts).

over the next two weeks – see here for dates in Auckland, Wellington, Sydney, Canberra and Melbourne. Heading for Los Angeles and San Francisco first week of May – let me know if you are interested in organizing book launches there. Then I’m done….. (Advance warning: jetlag and wall to wall powerpoint may interfere with the flow of blogposts).

Back to business:

Pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the twitter feed?

I’ve just subscribed to the Echo Chamber Club – that curated list of intelligent analysis from different political perspectives that I’ve been looking for h/t Irene Guijt

$15k to anyone with a decent plan for an ‘A Team’ (A is for Activist). A hoax or a really interesting attempt to seed fund the US activist ecosystem? Anyone know anything about it? h/t Ross Clarke

8 myths about migration. (includes aid doesn’t → less migration) h/t John Magrath

Tobacco taxes save lives, raise cash for health, education etc & are progressive. So great that they are on the rise. But government inaction still explains why so many people still smoke

Utterly rivetting (podcast or transcript, but be warned, very long). Tyler Cowen in conversation with Malcolm Gladwell h/t Ranil Dissayanake

‘St Patrick was an immigrant’. Kudos to Irish PM Enda Kenny for extolling migration & compassion on his St Patrick’s Day visit to the US President. Enjoy the discomfiture.

A new case must be made for aid. It rests on three legs.

Guest post from aid guru Simon Maxwell

Is the tide turning on aid? Famine in Africa has rekindled both media and public support. By 20th March, the UK’s Disasters Emergency Committee had raised £24m from the public in only six days for its East Africa Crisis appeal. Red Nose Day on 24th March provided another opportunity to demonstrate support. And on aid more generally, the Secretary of State for International Development, Priti Patel made a forceful speech at the BOND conference of UK NGOs on 20th March, making the case for action to tackle poverty, and celebrating UK leadership in international development.

So, have the critics in the press been seen off? Can the aid community stand down? No, for two reasons.

First, the dilemmas are real. Critics of aid adduce evidence on waste, corruption, or support for unsavoury regimes. Sometimes, they also raise more analytical concerns about the lack of evidence that aid contributes to growth. Or they make the point that aid on a large scale replaces domestic tax-raising, and thus undermines the relationship between a Government and its people. The recent UKIP policy paper, arguing for an 80% cut in UK aid, cites the Nobel prize winner, Angus Deaton, on the point about growth, and the renowned political scientists, Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson on taxation. Here, humanitarian aid is fine, and perhaps also health, but the rest is not.

In response, it is not enough simply to acknowledge the need to improve efficiency, or cite the undoubted benefits of aid: tackling disease, saving lives, and educating children. Some poor people do live in middle income countries whose Governments could do more, especially if they faced up to the need to tax the rich. Pakistan? Others do live in countries whose Governments have contested records on human rights. Rwanda? Ethiopia? Myanmar? And capital flight, tax evasion, and poor behaviour by private sector companies – all these exist. Making the case for aid must recognise complexity, long chains of causality, and the hard grind of effecting institutional and political change.

In response, it is not enough simply to acknowledge the need to improve efficiency, or cite the undoubted benefits of aid: tackling disease, saving lives, and educating children. Some poor people do live in middle income countries whose Governments could do more, especially if they faced up to the need to tax the rich. Pakistan? Others do live in countries whose Governments have contested records on human rights. Rwanda? Ethiopia? Myanmar? And capital flight, tax evasion, and poor behaviour by private sector companies – all these exist. Making the case for aid must recognise complexity, long chains of causality, and the hard grind of effecting institutional and political change.

In addition, and while it is true that the ultimate aim of aid is to tackle disease, save lives, and educate children, it may not be possible or right to target those issues directly. A generation ago, much aid was, indeed, spent on building health centres or primary schools. That was the right thing to do, because there was simply no money in newly-independent poor countries. Today, however, only 31 countries fall into the World Bank classification of ‘low income’. Of those, no fewer than 27 are classified by the OECD as ‘fragile states’, suffering political, security or environmental weakness. The OECD points to violence both as a key cause and symptom of low capacity – and says that the failure to address violence means that ‘development financing is out of touch with reality’.

Further, poverty in poor countries often results from problems at global level, or in countries far removed from the front line. Action on climate change is a case in point, impacting on those most vulnerable to droughts or storms, but needing action globally, and in high-emitting developed and emerging economies.

Thus, the new case for aid needs to rest on three legs.

First, understand the problem. This year, for example, humanitarian relief is essential to tackle famine in South Sudan, Yemen, Somalia and Northern Nigeria. But these famines are all man-made and will persist unless political solutions are found. We need to hear from those who understand the causes of conflict, and from the diplomats, generals and politicians. Who, really, has a five-point plan to resolve the conflict in South Sudan or Yemen?

Second, match the instruments to the need. The term ‘aid’ covers many options, from funding health centres and schools, to be sure, through to roads, ports, support to human rights bodies, election monitoring, and even policing. Aid donors have to make choices about what to provide. A new aid agenda implies radical refocusing of aid on the underlying causes, and muscular conditionality on core issues like human rights and democratisation. British aid initiatives like the Conflict, Security and Stabilisation Fund, the Prosperity Fund, or the International Climate Fund, offer new options for cross-Government working on non-traditional aid issues.

Third, tell a better story and take the public on a journey. The conventional wisdom is that the British public responds well to a case for aid which focuses on local interventions which help individual families, less well to more abstract concerns with global threats like security or climate change. But working with China or India to reduce carbon emissions matters. So does support to the South Sudan peace process. So does working with international business to create new manufacturing jobs. New aid needs new roots in the public mind.

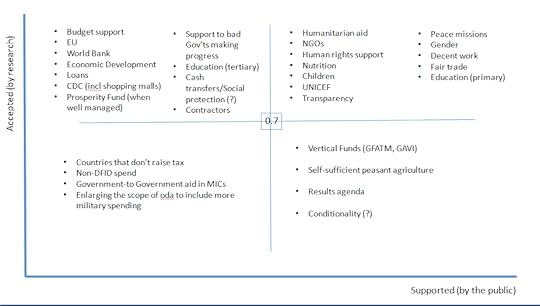

To start that conversation, here is a controversial figure. I have allocated aid instruments into four categories on two axes – the first on whether or not there is public support, the second on research support. In the top right hand corner are those interventions which both the public and the research base favour: working with NGOs, for example, or humanitarian relief. In the bottom right hand corner are interventions which the public supports but which have less research support. In the bottom right hand corner are interventions which nobody likes. And in the top left hand corner, the interventions which are supported by research but command less public support. I am completely aware that not one single entry in this Figure is uncontested. And, as always, the details matter: there is, for example, an active debate about whether humanitarian aid should be provided in cash or kind. The point, though, is to emphasise that any discussion of aid needs to begin by recognising its complexity.

A nuanced discussion of aid matters because a hurricane is threatening the consensus on international development. The crisis of faith in globalisation threatens to disrupt traditional routes to growth and poverty reduction, especially via labour intensive manufacturing, supported by free trade. Automation and the deployment of robots will disrupt and restructure the global jobs market. And the imperative of climate action, in all countries, will reconfigure markets and prices around the world. Aid had better be ready to deal with these: to take on future challenges, not relive those of the past.

Simon Maxwell is a researcher and policy analyst on international development. See www.simonmaxwell.eu.

March 24, 2017

What do aid agencies need to do to get serious on changing social norms?

Earlier this week I spent a day with Oxfam’s biggest cheeses, discussing how we should react to the rising tide of  nationalism and populism (if you think that’s a Northern concern, take a look at what is going on in India or the Philippines). One of the themes that emerged in the discussions was how to engage with social norms – the deeply held beliefs of what is natural, normal and acceptable that underpin a lot of human behaviour, including how people treat each other and how they vote.

nationalism and populism (if you think that’s a Northern concern, take a look at what is going on in India or the Philippines). One of the themes that emerged in the discussions was how to engage with social norms – the deeply held beliefs of what is natural, normal and acceptable that underpin a lot of human behaviour, including how people treat each other and how they vote.

It’s pretty common to hear progressive types (in which category I include Oxfam) worry that while they have been busy having geeky conversations on the evidence on this or that intervention/project, or the case for this or that policy change, they have ignored the tide of disillusionment with politics-as-usual that underpins the rise of populism. We need to engage the public in a wider conversation aimed at encouraging progressive norms, or opposing exclusionary ones.

Fair enough, but what struck me is just how much would need to change for that to become reality. What would a ‘guide to shifting norms’ cover? Here are a few thoughts; please add your own.

Analysis

There doesn’t seem to be much evidence on how to change norms. Eg what lies behind the increasing acceptance of the rights of people with disabilities? Or the age at which we deem chlldhood to end? Or even why dog owners routinely pick up their pooches’ pooh in my local park, something that was unimaginable a generation ago? How do deliberate attempts at change interact with the forces of demographic, technological or cultural change that also help drive norm shifts? This is one area where we really do need more research, both historical and current.

One of the areas of research I have come across is on violence against women, and a fascinating paper that showed that independent feminist movements are one of the strongest explanatory factors behind progress. A Filipina

Female Food Heroes, Tanzania

activist memorably described the best way to change laws and policies on gender rights as being like cooking a rice cake – you need simultaneous heat from the top (eg via the machinery of the UN) and heat from the bottom (from women’s movements).

As that paragraph suggests, up to now, a lot of work on norms has revolved around legislative change, whether through international laws and conventions, or at national level. One way of looking at the current populist backlash is that such a legal approach has overreached – the laws on issues such as racism or hate crimes have become so removed from the actual norms inside people’s heads that it is prompting a backlash, eg against ‘political correctness’. We need to find other, non-legal ways to close the gap.

We also probably need to involve more people from the disciplines that really ‘get’ norms – those that delve inside people’s hearts and minds, like psychology and anthropology, rather than the current intellectual dependence on economics, law and political science, which seem to have a pretty impoverished understanding of what goes on inside people’s heads.

What those disciplines could help us do is completely rethink our approach to ‘power analysis’. Although we pay lip service to ‘power within’ in terms of people’s sense of individual rights and agency, the kind of power analysis we use to design our projects and campaigns usually reverts straight back to the formal power of money and political influence. A ‘power within’ analysis would look at the moments in people’s lives when norms are formed or reformed, and the crucibles that forge them. I suspect that that would lead us to give priority to 3 arenas in particular: the family, faith organizations, and early years education (Aristotle: ‘give me a child until the age of 7 and I will show you the man’).

Action

How to put this knowledge to good use? Engaging seriously with norms would require different research, different messages, and different partners.

Firstly it would mean moving beyond the standard approach to trying to persuade the public by amassing a pile of  stats and evidence (memorably satirised by an Australian critic as ‘bad shit; facty, facty’ papers). One Oxfam big cheese suggested ‘start with the emotion, then follow up with the evidence’. Getting good at emotion and narrative is a whole skill in itself, and would require its own brand of evidence in terms of testing to identify the narratives that actually succeed in getting through to people. We do that on fundraising, and a bit on campaigns, but we would have to get both more imaginative on our narratives and more rigorous in our testing of them.

stats and evidence (memorably satirised by an Australian critic as ‘bad shit; facty, facty’ papers). One Oxfam big cheese suggested ‘start with the emotion, then follow up with the evidence’. Getting good at emotion and narrative is a whole skill in itself, and would require its own brand of evidence in terms of testing to identify the narratives that actually succeed in getting through to people. We do that on fundraising, and a bit on campaigns, but we would have to get both more imaginative on our narratives and more rigorous in our testing of them.

If you buy my earlier para on the forces driving norm formation, we would also need far more engagement with faith organizations, parents (especially mothers) and early years teachers. Our traditional partners (media, civil society organizations, academics) could also play a role, perhaps more in changing norms rather than their initial formation, but this would definitely entail a big shake-up of our partners. One example from our current work is the Female Food Heroes TV programme in Tanzania, which works to change norms around the roles of women in agriculture. Elsewhere there is evidence of the impact of soap operas on gender norms. More of that please!

Beyond the individual, societal norm shifts are often linked to critical junctures – eg look at the impact of war on women’s rights. Getting serious about norms would mean developing the ability to sense and respond to such moments as windows of opportunity.

Thoughts?

March 23, 2017

On Populism, Nationalism, Babies and Bathwater

A couple of Oxfamers were over from the US recently so ODI kindly pulled together a seriously stimulating conversation about life, theuniverse and everything. More specifically, how should ‘we’ – the aid community broadly defined – respond to the rising tide of nationalism, populism, and attacks on aid. It was Chatham House rules, so I’ve already told you too much, but here are some of the highlights:

North v South: The traditional focus of international development NGOs has been the ‘Global South’ (although North-South

Still true?

distinctions have become increasingly dubious). Should that now change? Some people stressed that we need to focus more on politics in the North, both because the risks to progressive values that we used to consider the consensus are now very real. In the UK ‘the winning side (on Brexit) is starting to change the minds of the losing side’ – people who weren’t bothered about immigration before now accept that it is ‘an issue’. ‘Ethics are like a muscle – they have to be exercised regularly or they will atrophy’.

There is also an instrumental argument: ‘we need to invest in the North, or we’ll lose the ability to have impact in the South.’ Specifically ‘we need to spend less time on policy and more on shaping public debate.’

In addition, maybe the current turmoil could provide the ‘window of opportunity’ to do more to refocus the long term agenda on promoting local control, stewardship, ownership etc, including giving higher priority to domestic taxation and the social contract between citizens and state.

Universalism v Nationalism: I was struck by how many people take the SDGs seriously as a symbol that we have moved beyond North-South to universalism, in which issues like rights, inequality and climate change are truly shared. But there was some fascinating scepticism in the room about how far ‘we’ can shift to a truly universalist approach. ‘Aren’t we part of the 1945-2015 consensus (on the division of the world into North and South)? Don’t we just need to get out of the way and let a new generation of people and organizations move towards universalism?’ That resonated with me, because I have seen just how hard it is for NGOs to move beyond a North-South frame in which the people we help are hungry, rural, oppressed and a long way away. Oxfam has been about to go urban since the late 1980s, according to successive strategic plans (thanks John Magrath for doing the digging on that!). It is very hard for development organizations to start working on shared agendas on tobacco, road traffic or obesity, however important they may be, simply because they fall so far outside our traditional narrative of what matters in developing countries.

Michael Gove would love this

Hug Populism, reject it or prepare for its collapse? ‘We have fundamentally miscalculated our fellow citizens’ in assuming a progressive consensus existed on at least some issues. What next? First, there is a risk of over-reacting – people have multiple identities bubbling away, and at different times, different ones come to the fore. We should still appeal to the better angels of people’s natures because those angels are still there.

But is it better to respond to rising nationalism by engaging with it, trying to understand it better, building bridges with some elements within it etc, or is that a fool’s errand in which we are forced to abandon principles and cross red lines with very little to show for it? Elements of the progressive agenda (inequality, industrial policy) feature in the populist rhetoric (if not their practice) so should we try and reclaim them for the progressive cause or pick other battles? In any case, what if the populist tide is peaking, shortly to come crashing down amid economic and political chaos? If so, wouldn’t it be better to start preparing messages, alliances, ideas etc in advance so that we are as ready as possible for that historical critical juncture when it comes?

Aid: and then there’s aid. We met the day after President Trump recommended a 28% cut in US aid, so

A view that’s gaining ground?

understandably we kept coming back to it. People contrasted 2015 and 2017. 2015 = an illusion of consensus, everyone debating the content of the SDGs; an ‘end of history’ moment when all that was required was better data. Fast forward two years and there is a ‘relentless assault’ on both sides of the Atlantic. When aid gets attacked, out of both self interest and commitment to the aid project, aid organizations spring to its defence. But isn’t that one reason why they are the wrong ones to lead on universalism? And anyway ‘whenever we try and move ‘beyond aid’, we do so by doing things through aid’. Ouch.

Overall, I was left confused and concerned (doubtless the mark of a good conversation). Concerned that the development community could jump into current northern battles on populism, Brexit etc not primarily because doing so is vital to helping the world end poverty in the long term, or because the issues that matter have suddenly become universal, but because the values of northern activists push them to get involved for personal reasons. If that happens, we risk forfeiting our legitimacy, which in the eyes of northern publics and policy makers is rooted in our links with and understanding of events in the South. And what do we gain if ‘Going Northern’ doesn’t add much to the existing progressive forces in the North?

And although many issues like equal rights, inequality etc are universal, some things (like famine) are not. There are still huge differences between rich and poor people and countries, and that matters. Take fragile and conflict–affected states – you simply can’t equate what goes on in rich countries and events in places such as Yemen or Somalia: perhaps unfortunately, they are the likely future of the aid industry, simply because more stable countries will graduate through a combination of growth, poverty reduction and rising taxation. Whatever we do in the North, we need to ask ourselves whether it is relevant and helpful to the communities in those places. If the answer is ‘not really’, we should worry about that.

I’m now stuck in a global confab of Oxfam big cheeses on similar subjects – will report back on anything new that emerges.

March 22, 2017

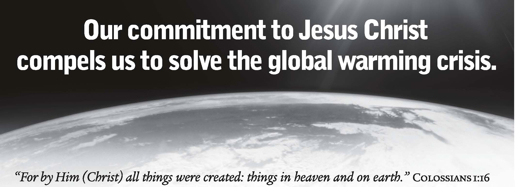

How do we shift social norms on climate change?

Spent an enjoyable hour discussing strategy with exfamer Kate Norgrove, who now runs the Purpose Climate Lab (see here for the kind of thing they do). Kate wanted to discuss their theory of change (what else?). Purpose has identified what it sees as a gap: while lots of organizations are working on climate change in ways that are oppositional or focussing on laws and policies, Purpose wants to contribute by tackling long term social norms in order to shift what people believe and therefore how they act in ways that support the climate. Interesting.

Spent an enjoyable hour discussing strategy with exfamer Kate Norgrove, who now runs the Purpose Climate Lab (see here for the kind of thing they do). Kate wanted to discuss their theory of change (what else?). Purpose has identified what it sees as a gap: while lots of organizations are working on climate change in ways that are oppositional or focussing on laws and policies, Purpose wants to contribute by tackling long term social norms in order to shift what people believe and therefore how they act in ways that support the climate. Interesting.

Purpose Climate Lab (PCL)’s mission statement is ‘We believe that by presenting a positive vision of the future and by mobilizing people where they are – in cities, regions, homes, businesses and through culture – we will change beliefs, behavior, politics and policy to accelerate the adoption and build the ambition of just climate solutions.’ That certainly resonates with Alex Evans’ interesting work on the importance of building positive narratives. It also highlights for me a lack of research on what works in terms of deliberate efforts to change social norms – I’ve seen specific studies on equal marriage and violence against women, but can people recommend anything more systematic?

I got out my favourite 2×2 (see diagram) and asked Kate which quadrant she thought PCL is largely working in.  She thought bottom right – for example, they’re doing lots of testing of messages with different constituencies like evangelical Christians in the US (they have really got the need to engage with faith groups, which is great). I wasn’t convinced – from what she told me, seems more like a good version of upper right – try something, with the aim of going to scale, but have decent feedback loops in place to see how you are doing and make necessary course corrections.

She thought bottom right – for example, they’re doing lots of testing of messages with different constituencies like evangelical Christians in the US (they have really got the need to engage with faith groups, which is great). I wasn’t convinced – from what she told me, seems more like a good version of upper right – try something, with the aim of going to scale, but have decent feedback loops in place to see how you are doing and make necessary course corrections.

But what could they be doing in the other quadrants?

Bottom Right: really tackling this would mean coming up with as narrow a problem statement as possible, eg ‘how do we change the attitudes of 14-16 year old boys towards cars’ and then deliberately trying parallel experiments to see which one works. Getting lots of unusual suspects in the room (musicians, gamers, polling companies) might generate a wider and more interesting range of experiments. It could also mean taking a deliberate portfolio approach – seeing your different projects or campaigns as a whole, and seeking a spread of craziness: a mix of solid, traditional campaigns, and then some high risk/high return outliers that are more likely to fail, but if they work, could go large.

Top Left: Cue rant on the need to anticipate and respond to critical junctures. If you are trying to shift the way people feel about climate change and planetary boundaries, the best time to do so is when something awful happens – eg when Manhattan or Somerset are under water. We know this will happen some time (known unknowns) so we  don’t need to wait – we can put the building blocks in place for a fast and ambitious response when the window of opportunity arises. That could include getting the research 80% written (add the last 20% dependent on the event itself), or setting up the high level network so that within a day of the flood, you have bishops, celebs and Nobel laureates all standing up to their waists in flood water calling on citizens to take action.

don’t need to wait – we can put the building blocks in place for a fast and ambitious response when the window of opportunity arises. That could include getting the research 80% written (add the last 20% dependent on the event itself), or setting up the high level network so that within a day of the flood, you have bishops, celebs and Nobel laureates all standing up to their waists in flood water calling on citizens to take action.

Bottom Left: Positive Deviance means that somewhere the system is usually already throwing up solutions (complete or partial) to any given problem. So which communities, sectors, companies are already shifting social norms on climate change and the planet? The first task should surely be to identify those, but activists typically forget to look, perhaps because they are so keen to jump in and start changing the world.

Framing: PCL is determined to present a ‘positive vision of the future’, for example by emphasizing social support for renewables, which is very appealing at first glance, but I wonder if it works (and when)? Oxfam has often struggled to get positive messages across in its fundraising and campaigns – the media aren’t interested; the urgency is lacking. Where have positive vision campaigns on climate or otherwise worked in the past? Perhaps time to consult Friends of the Earth’s work on the history of 19th and 20th Century campaigns in the UK?

Kate said she was happy for me to consult FP2P readers on this, so what advice can you add? If you’re too bashful to hold forth on the blog, please contact Kate via twitter on @katenorgrove (or ask me nicely and I’ll give you her email).

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers