Duncan Green's Blog, page 117

June 1, 2017

The imaginary advocate, the benefits of Command and Control, and why I’m just channelling Hayek

Continuing the download from the recent LSE-ODI workshop on ‘new experimentalism’ was this thought-provoking description by  David Kennedy of the ‘imaginary advocate’, the assumed individual beyond How Change Happens and, by extension, a lot of NGO advocacy. Might be a very interesting addition to the endless awaydays, strategic planning processes etc to ask people to try and spell out the imaginary subjects of their own organization’s work, and then critique them.

David Kennedy of the ‘imaginary advocate’, the assumed individual beyond How Change Happens and, by extension, a lot of NGO advocacy. Might be a very interesting addition to the endless awaydays, strategic planning processes etc to ask people to try and spell out the imaginary subjects of their own organization’s work, and then critique them.

‘What kind of person makes this plausible? The person – the development professional, the advocate – needed for new governance is not “naturally occurring” in culture. It needs to be made – that’s why, I presume, Duncan wrote the book. We’ll need to train people to be like this.

The new governance person fits well in the terrain of modern managerial and technocratic culture. There are some taken for granteds – you work for an institution, you have a “client” or “cause”. You favour it, but you’re not obsessed, you have a kind of disenchanted distance from your projects.

You feel a certain sense of superiority to the less agile normal manager in big institutions — it’s not arrogance, we’re against that, but still, the Fordist manager is not entrepreneurial, the welfare state bureaucrat is not transversely agile, etc.

You have a range of possible points of engagement, access, tools. You have….funding. You have some autonomy. And the situation is not too too scary.

Which says something about other people. This is not an us/them world of struggle. Other people are more friction than resistance – you are active and they more inertia and friction than opposition. Or, if in opposition, they are also reasonable – they also have interests, they need to be understood, heard, engaged.

Somehow malevolent self-dealing objectives fit less well with this set of tools. The greedy will not want to listen or engage, will be too short term, will miss the legitimacy clues, etc.

But I wonder. This all seems more romantic than optimistic. Romantic about the client, the local, to whom we should listen, who might have found answers already. Romantic about human potential for creative action in the public interest if we throw off the bonds of form.’

Once David had finished with me, the LSE’s Stephen Humphreys got stuck in with some contrarian thinking on the merits of command and control, and why I’m really just channelling Hayek.

Come back, all is forgiven?

‘The old Weberian bureaucracy was an intention-machine, it carried out commands. It baked cakes. But we have had it in for command-and-control for a few decades now. It’s been the butt of jokes and derision on the development circuit’s equivalent of late night TV. And at last, it seems to have finally gone away.

No more command-and-control. Do we miss it? I suspect we do. But rather than admit we do, maybe it’s better to celebrate how much more interesting—how much more liberating—this new smoggy uncertainty is, this public policy Brownian motion. Command and control was always such a drag, and now we are free! Free to play.

But is there not too a sense of lowered ambition? Of falling expectations?

Duncan’s system-complexity is of course reminiscent of Hayek. And in particular the central role that ignorance plays in Hayek’s universe, in his state. Hayek loved to remind us that we don’t know very much, and we can’t really predict the consequences of our actions. We are fundamentally ignorant. For Hayek there wasn’t a lot of point in trying to address this ignorance. It’s constitutive. The solution was rather to let it go. Embrace ignorance.

The market, for Hayek, is like Duncan’s flock of starlings. It doesn’t know how it knows. It sort of intuits frictionlessness out of chaos.

I had the sense that Duncan is inviting us into a Hayekian mindset, and although it is not one in which the market altogether displaces the state—at least I don’t think this is what Duncan intends—it is nevertheless one in which the state learns from the market. It becomes market-like. The point is the market doesn’t know or need to know. That used to be the state’s job.’

That lot is going to take some digesting – thoughts welcome.

And for those of you wondering who this Hayek guy is, here’s his legendary geek-rap battle with Keynes

May 31, 2017

The case against optimism: A Harvard Law Prof critiques How Change Happens

Last week I had the ‘on the psychotherapist’s couch’ experience of having the assumptions behind How Change Happens put under the

But what about optimism of the intellect?

microscope by two very big brains – Harvard’s David Kennedy and LSE’s Stephen Humphreys. This was part of a joint LSE/ODI seminar on ‘new experimentalism’ (which seems to be the legal studies equivalent of Adaptive Management). I thought their critiques were brilliant (and lyrical – do lawyers write better?) – here are some excerpts.

First David, who is a prof at Harvard Law School on the weakness and oversights of optimism:

“Duncan’s chapters are quite astonishing really. He distils a lifetime of advocacy and impassioned work into page after page of hopeful advice for the young activist. Whatever the case for pessimism, as a professional style, optimism has a lot of appeal. It is worth trying to understand how this “bright side” vision is sustained. How does Duncan hold firmly to his sunny disposition across chapters which might well have brushed up against this or that difficulty, qualification, bad experience – dark side?

In at least two ways that are characteristic of many seeking to do good in the world.

First, by a sense of evolution and progress, which leaves our optimist comfortably modest. The pragmatic experimentalist advocate accepts that you do what you can — and what you can do is often a lot – but the big things await the motions of history.

Luckily, in the long run, history is on our side. Why should we be so confident things will work out? Duncan offers a kind of social evolutionism, midwifed by the steadying hand of “legitimacy.” Bad things just can’t go on forever, people won’t stand for it.

In this vision, the center generally will hold – but don’t worry, it bends slowly toward justice. In our own small ways we can all help it along. And should things fail to hold, that’s ok too. Historical ruptures create opportunities to move things forward.

In what I read, Duncan doesn’t offer instruction on how to create a rupture – or how to avoid one. They seem to just happen — perhaps triggered by a legitimacy crisis. But while pursuing one’s routine work, one should be ready.

There is some truth here, of course. Governments can be so obtuse to outcomes that people revolt. Bungling Katrina, bungling Iraq, bungling the economy – in my country these did diminish the government’s authority and ultimately facilitated it’s replacement, given, of course, a whole set of surrounding institutions and historical habits which may not be available, or not work in just this way in other times and places.

I just don’t share the optimism. Most bad things are amazingly durable. Take racial inequality in the US – we might as well admit it is constitutional to offload X percent of the population indefinitely, so long as you do it in the right way. “Doing it right” changes, but the inequality does not. Or the predominance of private capital over public power — from Medici to Citibank. Or of property over labor, and so on.

It seems probable that “development” will often demand a rupture which the existing settlement not only prevents but itself delegitimates.

Truth to Power or Dark Arts: No and No, so what’s left?

A second background idea which seems to keep the optimism going is a relentless focus on the good guys, as if people involved in rulership normally rather than very exceptionally are people of good heart, people who want to solve problems, who are trying to do things like “develop” the society.

And that the state normally evolves to be a public interest aggregator and policy maker rather than a “swamp” of lobbying and influence peddling, garnished with promises of undertaking something called “public service.” Or that the state is different from the private sector in this. Ah….if only…..

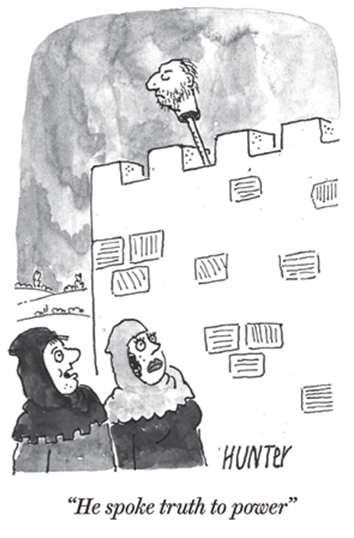

Duncan seems to exclude two kinds of projects. On the one hand, standing fully outside, speaking truth to power – he finds that arrogant, ineffective, insufficiently attuned to possibilities within the terrain of the existing order. On the other hand, violence, coercion and the dark arts.

Both exclusions are puzzling. Take coercive violence. Governance – that for which one advocates – is a coercive enterprise. There will be losers. This isn’t just something other people do.

And even war – the largest “new experimentalism” has seen warfare for regime change in the name of human rights. By far the most expensive and culturally visible new governance endeavor. And an astonishing failure.

Or take COIN — the McMaster idea for defeating an insurgency is remarkably parallel – longer term local listening, flexibility, initiative, the officer as innovator, don’t rely on technology, it’s a human and cultural situation, etc.

When we push coercion out one side and “speaking truth to power” out the other, we’re left with a rather impoverished menu of governance tools.

It would be better, I think, to say that humanitariansm has two voices, two postures, irreconcilably in struggle with one another: outsider truth and insider collaboration. And each has a vice for which the other is a remedy — idolatry and complicity. But balance is not a solution — this is an enduring human tragedy, a conundrum, not a technical challenge for savvy management.

And his conclusion?

I guess the way I see it, the world out there is pretty tough. There are really bad guys – some of them are local, some of them are leaders. Really smart people are deep into back scratching, rent seeking, etc. — not the kind of thing which would yield to experimental adjustment or agile activism. We must learn to struggle better, not manage better.

I’d prefer we start with struggle, learn to map the terrain with a cold eye, keep a full range of tools at our disposal from coercion thru complicity and advocacy to outsider denunciation. And that we learn the dark arts of resistance and rupture as intensely as those of strategic balancing and experimental management.’

Tomorrow, more from David Kennedy, plus Stephen Humphreys, an Associate Prof of International Law at the LSE, on the merits of command and control, and why I’m really just channelling Hayek……

And ‘the bright side’? Sorry, that means obligatory Monty Python video

May 30, 2017

What does Feminist Social Innovation look like?

Guest post from Chloe Safier

In the global development world, there are a lot of conversations about social innovation and (separately) a lot of discussions about  feminist approaches to development and women’s rights. Social innovation labs, incubators and accelerators are popping up everywhere, from San Francisco to Beirut to Delhi. Major development actors like the Gates Foundation are issuing ‘challenges’ to advance innovation and cultivate the next big idea- whether that’s a new condom or a better way of combatting disease. At the same time, there is a growing recognition of gender inequality and the injustices that women and girls face globally, from the UN to the media to governments and beyond.

feminist approaches to development and women’s rights. Social innovation labs, incubators and accelerators are popping up everywhere, from San Francisco to Beirut to Delhi. Major development actors like the Gates Foundation are issuing ‘challenges’ to advance innovation and cultivate the next big idea- whether that’s a new condom or a better way of combatting disease. At the same time, there is a growing recognition of gender inequality and the injustices that women and girls face globally, from the UN to the media to governments and beyond.

Social innovation and feminist approaches to development share many of the same principles and a high degree of overlap. Many of those who work in social innovation employ feminist principles in their leadership or processes, or are developing initiatives that advance women’s rights. Many women’s rights and feminist organizations are being innovative without formal links to social innovation.

So what happens when you put the two together? FRIDA | The Young Feminist Fund, Global Fund for Women, Oxfam and the Young Foundation have been finding out for the past year, as part of designing a new program called the Roots Lab. The Roots Lab is a social innovation incubator: a two-year program designed to catalyze social change driven by young women activists. Through consultations with organizations and companies dedicated to advancing either women’s rights or social innovation, we developed a laboratory model that will give young women the tools, skills, networks, and financial support they need to take their game-changing ideas (to advance women’s rights) and make them a reality. A pilot program will kick off in Lebanon next month.

So what happens when you put the two together? FRIDA | The Young Feminist Fund, Global Fund for Women, Oxfam and the Young Foundation have been finding out for the past year, as part of designing a new program called the Roots Lab. The Roots Lab is a social innovation incubator: a two-year program designed to catalyze social change driven by young women activists. Through consultations with organizations and companies dedicated to advancing either women’s rights or social innovation, we developed a laboratory model that will give young women the tools, skills, networks, and financial support they need to take their game-changing ideas (to advance women’s rights) and make them a reality. A pilot program will kick off in Lebanon next month.

There’s plenty of examples to draw on. In Fiji, a group of young women volunteers built a new technology that allowed them to produce a monthly radio broadcast from a “suitcase radio,” bringing radio production to rural areas and creating the Pacific’s first woman-led community radio network. Harassmap combines technology, activism and social innovation to address sexual assault and harassment in Egypt by using SMS mobile technology to allow people who have been harassed or assaulted to report those incidences, where they are mapped for the purposes of advocacy, policy change and research.

In developing the Roots Lab, here is some of what we learned about from our interviews with innovators:

In building a new program, communicate the process clearly from the outset, and keep the model simple enough to make that possible.

To advance innovation, bring people from multiple sectors together in a structured way, but allow for flexibility in how those people relate to each other in the spaces you create.

As stated in Stanford’s Center for Innovation definition, “social innovation focuses attention on the ideas and solutions that create social value — as well as the processes through which they are generated, not just on individuals and organizations.” So make sure process is a big part of the focus.

Learn quickly from your mistakes, adapt, and get comfortable with failure. If you do fail, fail fast.

Create space for people to learn from each other, and push people to realize the potential in those around them.

And most importantly, open up funding streams for riskier ventures, from non-traditional leaders, if you really want to see new ideas for change.

We also spoke to young feminist activists and grassroots organizations around the world, including in Tunisia, Zambia, the US, and South Africa as well as more established women’s rights and feminist organizations in the UK and Lebanon. Here’s some of what we  heard:

heard:

Young women have great ideas for creating change, but they’re struggling to find funds, access and the network to get their ideas off the ground. In one design session in Beirut last month, a young activist trialing exciting new work told us that the only two funders globally whose criteria she fit were already in the room – Global Fund for Women and FRIDA | The Young Feminist Fund.

New technologies – especially cell phones and social networking sites like Facebook- are hugely advantageous, but are also creating risks (of increased government surveillance, trolling or privacy violations).

In most parts of the world, established women’s rights organizations, are struggling to cover basic operating costs. The average women’s rights organization has a median annual income of US$20,000. This leaves little room for trying and testing new things, or for creating space for a new generation of leaders.

Young women told us they have struggled to connect with the networks and contacts it would take to mobilize their ideas because they didn’t know who to talk to, or didn’t think their ideas would be taken seriously.

Young women activists said they felt left out by the existing women’s rights organizations, and some young women felt included but marginalized because of their age and inexperience.

Younger women want to learn from the generation of women activists who came before them, and they want to share what they know and the challenges they’re facing that are unique to their generation, but there are too few opportunities for that exchange.

Many established women’s rights organizations want to connect with younger women activists, particularly around employing social media and engaging young women in campaigns and policy influencing efforts.

Our conclusion? If you bring people and organizations from across different sectors together (one of the drivers of social innovation) applying a feminist approach means doing so in a way that recognizes and accounts for the intersectional identities and power inequalities that exist in the room. This means providing redress, in the form of naming power dynamics explicitly and creating more space for those with less power to speak and be heard. Otherwise the people who come to the space with the most power (due to their race, gender, class, privilege, ability, age or status) can easily dominate the space – often unknowingly. That is likely to mean that the innovation itself reflects the privilege of those who create it. The history of gender and development can help us predict that if social innovation doesn’t challenge global patriarchal norms that say men have and hold the most power, access to, and control over resources, gendered inequality will be perpetuated.

Our conclusion? If you bring people and organizations from across different sectors together (one of the drivers of social innovation) applying a feminist approach means doing so in a way that recognizes and accounts for the intersectional identities and power inequalities that exist in the room. This means providing redress, in the form of naming power dynamics explicitly and creating more space for those with less power to speak and be heard. Otherwise the people who come to the space with the most power (due to their race, gender, class, privilege, ability, age or status) can easily dominate the space – often unknowingly. That is likely to mean that the innovation itself reflects the privilege of those who create it. The history of gender and development can help us predict that if social innovation doesn’t challenge global patriarchal norms that say men have and hold the most power, access to, and control over resources, gendered inequality will be perpetuated.

But there are real challenges to getting young feminist activists and social innovators to work together, especially when the latter come from the private sector. Taking money from a corporate funder risks activists seeing their messages or brand co-opted by the corporate donor. But staying ‘clean’ may also mean staying marginal, and losing out on access to funding and influence in networks.

An important caveat, however, is that funding or supporting feminist innovation shouldn’t come at the expense of funding existing feminist or women’s rights work; it should be in addition to increased core support. Innovation isn’t always the answer, and often feminist organizations already know what works – they just don’t have the available resources at their disposal. Compelling organizations to take up innovation (through persuasion or by dangling funds) is not in line with feminist approaches to development as it means that those who receive the funds aren’t themselves defining the agenda. Feminist organizations and those who fund them can build more space for innovation within feminist spaces by opening up new funding streams and building on existing ones, and investing in dedicated feminist innovation spaces. We hope the Roots Lab will be one of them.

Chloe Safier is an independent gender and women’s rights consultant who worked as the Program Design Lead for The Roots Lab. Follow her work at @chloelenas or chloesafier.com

For further information about The Roots Lab, see here or contact Emily Brown at Oxfam embrown@oxfam.org.uk .

The Roots Lab in Lebanon has been made possible with the generous support of The Open Society Foundations, ShineMaker Foundation and Oxfam.

May 29, 2017

Links I Liked

Not new but bears repeating/retweeting: “The number of people in extreme poverty fell by 130,000 since yesterday”. Should have  been headline news every day since 1990. Thanks Max Roser.

been headline news every day since 1990. Thanks Max Roser.

World Bank chief economist Paul Romer forced to give up management of WB research department, having alienated a lot of his colleagues. His crimes included ‘asking for shorter emails and insisting presentations get straight to the point’. Here’s his internal blog post on good writing, which he subsequently made public.

Scorecard diplomacy: How grades drive behaviour in international relations. Indexes and league tables as a new form of soft power.

Some Oxfam plugs:

Nigeria 1960-2005: $20 trillion stolen from the Treasury by public office holders. That’s a lot of zeroes (13). From the new Oxfam Nigeria inequality report

How do we measure women’s empowerment? Latest from Oxfam’s good ‘Real Geek’ platform introduces a new ‘how to’ guide

And back to the mesmerizing spectacle of US politics:

Details of White House proposed aid cuts. Down 32% on 2017 levels. Humanitarian, long term development, peacekeeping all scheduled for cuts. Let’s hope Congress steps up.

Trump body language came under scrutiny on social media. Gimme the handshake, gimme the limelight.

Is China’s humungous One Belt One Road scheme a better development policy than Western aid? Branko Milanovic typically thoughtful and challenging.

Extraordinary film making. Extraordinary lives. Syria’s tragedy is not just about its children

May 25, 2017

‘I don’t need a Plan, I need a better Radar’ – how can we rethink Strategic Planning?

I was in Washington this week helping the International Budget Partnership think about its future direction. There’s a certain rhythm to these exercises – some research on external trends, consultation with partners and staff, maybe bring in some outside facilitators, then sit down and say ‘so what should we be doing differently?’ These days, there is often an initial session on complexity and systems thinking, but I’m starting to recognize a pattern – the implications of that initial session are largely ignored as we default back to theories of change, accompanied by lists of priorities and activities, culminating in a more or less conventional ‘Strategic Plan’, which then disappears onto the shelf/into the folder, never to be seen again until the next Strategic Planning process.

a certain rhythm to these exercises – some research on external trends, consultation with partners and staff, maybe bring in some outside facilitators, then sit down and say ‘so what should we be doing differently?’ These days, there is often an initial session on complexity and systems thinking, but I’m starting to recognize a pattern – the implications of that initial session are largely ignored as we default back to theories of change, accompanied by lists of priorities and activities, culminating in a more or less conventional ‘Strategic Plan’, which then disappears onto the shelf/into the folder, never to be seen again until the next Strategic Planning process.

It’s too early to say if IBP will go down this route, but I was struck by one comment from Albert van Zyl, IBP’s battle-hardened South Africa director: ‘I don’t need a plan, I need a better radar’. So what might a Strategic Radar look like? Here are some thoughts to get the comments flowing:

Who is ‘We’?

Strategic Vision: the kind of world we are seeking to build/support. This should encapsulate the values that get people out of bed and into the office every morning, inspiring them to soldier on, in spite of setbacks and annoyances. It could also include some ‘big hairy audacious goals’ for changing the world, and some guiding principles for how we work.

Rules of thumb: the kinds of heuristics we employ in our daily work, which reflect the born organization’s identity, direction and values. According to Ben Ramalingam, the US marines have 3 such rules in combat situations: ‘stay in communication, take the high ground, keep moving’ and then improvise the rest. My candidate for Oxfam’s rules of thumb would include questions like ‘who gets what?’ (i.e. power and distribution); ‘what’s the impact on women?’ and ‘what do local people, organizations and partners say?’ Interesting that we never acknowledge, identify or critique those rules of thumb – maybe we should.

Theory of Change

I am now convinced we should routinely distinguish a theory of change from a theory of action (discussed below). A ToC is about the system, not about us. How do we think the system is changing on the issues we care about? Writing that down will surface our assumptions about the way the world works, which can subsequently be tested/revised in the light of experience

I am now convinced we should routinely distinguish a theory of change from a theory of action (discussed below). A ToC is about the system, not about us. How do we think the system is changing on the issues we care about? Writing that down will surface our assumptions about the way the world works, which can subsequently be tested/revised in the light of experience

Theory of Action

Now it’s time to talk about us. What contribution do we think we can make to bringing about change, and how will it work? Again, assumptions that are usually implicit can be dragged into the daylight, exposed to scrutiny and experience, and revised.

Strategic Process: I am becoming a big fan of the ‘searchframe’ proposed by the Building State Capability crew. As an organization you need to be clear on how you intend to work ‘going forward’ as management types say. That tells staff what to expect, and reassures potential funders. The searchframe combines that assurance with a commitment to being adaptive/responsive to context, by saying ‘here’s our plan for the next X months, then we will step back and review what has/hasn’t worked, revisit our stakeholder and power analyses, ask what new opportunities/threats have emerged and come up with a plan for the subsequent X months. That will be repeated every X months in the life of the project.’ A Strategic Process would set out in advance how often you intend to step back, how you would do so (all staff or some? External facilitators or internal?)

But some commitments and initiatives require years of commitment up front – helping local organizations build their capacity for example, so a Strategic Process would have to include some longer timeframes too.

their capacity for example, so a Strategic Process would have to include some longer timeframes too.

Partnerships strategy: the kinds of organization and individual you will be seeking to work with over the next few years.

But go easy on the diagrams. Our conversations only increased my scepticism about the diagrammatic version of theories of change/action, which seems increasingly de rigueur. You know the kind of thing – lots of boxes and connecting arrows that aim to show that we know how it the system works, and have clever plans to influence it. The diagrams might be useful when you’re drawing them up from scratch – thinking about the way the organization works, the way the different bits fit together, but once on paper the diagram too easily becomes tyrannical, especially for new arrivals who had nothing to do with their creation – a thought deadener that drips linearity into our thinking and ignores at least two crucial areas: change dynamics – unpredictable critical junctures, windows of opportunity etc that in practice play a central role in many change processes, and people – the relationships, wisdom, judgement that will almost inevitably determine success. Maybe we should have Theories of Change diagrams that self destruct in 10 seconds, a la Mission Impossible?

Operationalization

What does the organization need to put in place to get started and keep learning and adapting as th work develops?

Strategic investment: Capacity follows money, and you would need to set out how you intend to spend money differently, what new skills you want to bring into the organization (e.g. power analysis and political smarts), whether you need new areas of operation etc.

Strategic opportunism: How is the organization going to put in place the skills to recognize new windows of opportunity (‘Fortune favours the prepared mind’ Louis Pasteur) and the systems to respond to that recognition, e.g. by moving money and people in rapid response to new openings (as we do, say, in emergencies)?

This checklist has got a lot longer as I’ve run it past people at IBP and the facilitators, MAG, and is starting to feel a bit cumbersome. It may be that a particular strategic planning exercise won’t need to include all the pieces, but I’ve tried to nail down those elements that will still be relevant in 6, 12, 18 or 100 months time, rather than languishing unread in the planning file.

Any thoughts? Chip in and it may help IBP try something a bit different this time. Whenever I come up with something like this, someone usually says ‘old wine in new bottles’ and/or ‘we tried that in the 1990s – it didn’t work’. Still, got to keep plugging away, eh?

May 24, 2017

Can Hegel (and Geoff Mulgan) chart a new progressive agenda?

Geoff Mulgan is one of the UK’s most original thinkers about the future of society. He set up the thinktank Demos, advised the early Blair government, and now runs NESTA (an ‘innovation foundation). According to Wikipedia he even trained as a Buddhist monk in Sri Lanka. I recently came across his essay on a progressive response to Brexit, Trump etc – it’s brilliant, and although aimed at northern publics, has plenty of resonance for global debates. But at over 20 pages, it risks being condemned to the outer darkness of TL;DR – the depressing acronym for ‘Too Long; Didn’t Read’. So here’s some excerpts to whet your appetites:

advised the early Blair government, and now runs NESTA (an ‘innovation foundation). According to Wikipedia he even trained as a Buddhist monk in Sri Lanka. I recently came across his essay on a progressive response to Brexit, Trump etc – it’s brilliant, and although aimed at northern publics, has plenty of resonance for global debates. But at over 20 pages, it risks being condemned to the outer darkness of TL;DR – the depressing acronym for ‘Too Long; Didn’t Read’. So here’s some excerpts to whet your appetites:

‘Hegel implied that we should see history, and progress, not as a straight line but rather as a zigzag, shaped by the ways in which people bump into barriers, or face disappointments, and then readjust their course. This framework fits well with where we stand today. The ‘thesis’ that has dominated mainstream politics for the last generation – and continues to be articulated shrilly by many proponents – is the claim that the combination of globalisation, technological progress and liberalisation empowers the great majority.

‘Hegel implied that we should see history, and progress, not as a straight line but rather as a zigzag, shaped by the ways in which people bump into barriers, or face disappointments, and then readjust their course. This framework fits well with where we stand today. The ‘thesis’ that has dominated mainstream politics for the last generation – and continues to be articulated shrilly by many proponents – is the claim that the combination of globalisation, technological progress and liberalisation empowers the great majority.

The antithesis, which, in part, fuelled the votes for Brexit and Trump, as well as the rise of populist parties and populist authoritarian leaders in Europe and beyond, is the argument that this technocratic combination merely empowers a minority and disempowers the majority of citizens.

A more progressive synthesis needs to avoid both nostalgia and the fetishisation of globalisation and technological advance as ends in themselves, rather than as means. And it needs to take seriously the complaints of the bypassed and excluded, the hundreds of millions who feel left behind in a slow lane while the rest of the world hurtles off into a future that’s not for them.’

The paper goes into plenty of detail unpacking the thesis and antithesis, but I’ll stick to the proposed synthesis.

‘At the heart of that needs to be a new approach to power. If the main source of the strident antithesis is a sense of disempowerment then this is where an alternative has to start – not only to shifting power to the people, but also ensuring that people feel that power as well.

We need, in short, to apply a power test to each area of public policy: do policies adequately share power? Are they designed in ways that will help people to feel power over their own lives?’

He then sets out some of the answers in a dozen areas of policy. I’ve included headers and the odd particularly striking para:

striking para:

Education that grows makers and shapers

Adult skills taken seriously: Few doubt that millions of jobs will either disappear or change as a result of automation, from manufacturing to services and the professions. As that reality dawns, attention will turn to adult education and retraining, to help the millions at risk of losing their jobs adapt to growing industries.

People powered health: Similar considerations apply in health. We need the best possible healthcare, provided by experts using the best available technologies. But we also need patients and the public to take more power and responsibility for their own health.

Welfare to address risk and precarity: The crucial question is whether welfare addresses the most important current needs, and whether it uses the most effective current tools. In many countries, welfare fails both tests. It doesn’t adequately address burgeoning needs for eldercare, or security in precarious labour markets. And it makes little use of digital tools that could make it feasible for governments to offer a much wider range of financial supports, including loans repaid over the lifetime.

Open and inclusive innovation

The fourth industrial revolution reoriented to needs that matter: On the present trajectory, the 4IR promises great benefits. But it also risks leading to a widening divide between vanguards and the rest, accelerating job destruction ahead of job creation; and introducing potentially big threats to personal privacy and cybersecurity.

[Getting to a better place] requires fresh thinking about regulation, about supply chains, taxation and law. It takes us to new ideas like Sweden’s recently introduced tax breaks for maintenance of goods – an attempt to shift the economy away from waste, while also creating jobs; and to some of the technological possibilities around blockchain.

Democracy upgraded: The most problematic part of the current situation is the stagnation of democracy: the view that all politicians are corrupt and self-interested. This fuels the passive anger of electorates, who then revert to faith in populist leaders as the solution to disempowerment.

Democracy upgraded: The most problematic part of the current situation is the stagnation of democracy: the view that all politicians are corrupt and self-interested. This fuels the passive anger of electorates, who then revert to faith in populist leaders as the solution to disempowerment.

The alternative is to reshape democracy so that it does provide more genuine power to citizens. That’s not easy, and there have been many false starts and false promises of push-button instant democracy.

The best of these schemes make government more like a collaborative, reflective process of deliberation rather than a permanent referendum. They have the virtue of not only involving the public but also educating them along the way, so, for example, the trade-offs of any decision can be made clear. Reforms to upgrade democracy must be part of the new synthesis too, as a counter to the trends towards a democracy built around spin, deceit and bluster.

Data and the internet: The search for very different models of the internet is bound to become more prominent over the next few years, and will involve power. How can citizens control more of the data that matters to them? How can these great new infrastructures be more accountable?

Migration and democracy: There’s clearly a tension between democracy and open borders. The new synthesis will have to include more overt democratic control over the terms of migration: who comes and on what terms, whether as worker, student, tourist or patient. The only kinds of democracy we know are based in places and so it’s not surprising that control over place is so important to feelings of empowerment.

Government experimentation and adaptation

New platforms and infrastructures for the public

Fleshing out programmes of this kind won’t be easy. But this is the serious work that must start. It requires us to think dialectically, achieving a balance between conflicting ideas, rather than taking them to their logical conclusions, the consistent mistake of the more extreme partisans of globalisation.’

Good eh? So why not click through to the full essay.

May 23, 2017

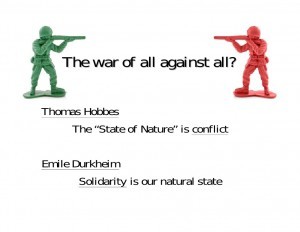

Why is life in fragile/conflict states not more ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short’? New research programme on ‘Public Authority’

Thomas Hobbes argued that states are essential to guarantee security. In their absence there would be a ‘war of all against all’ in which

Doesn’t Happen. Why not?

life would be ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short’. But in most fragile and conflict affected areas, that degree of bloodbath is strikingly absent – individuals, families and communities find ways to survive and resolve disputes in ways that stop short of a massacre, but often bypass formal state institutions. How do they do it?

Helping answer that question is going to be part of my work for the next few years, as I take up a role in a new LSE-run ‘Centre for Public Authority and International Development’ (CPAID, hosted by the Firoz Lalji Centre for Africa). Building on previous LSE research centres such as the Justice and Security Research Programme, the centre will look at countries involved in prolonged conflict, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, Central African Republic, South Sudan, Somalia and Burundi, as well as the now relatively peaceful states of Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Uganda and Ethiopia.

The hypothesis we aim to test is in the title of the new Centre. In the clear (if rather dense) prose of the project document:

‘CPAID uses the term ‘public authority’ to refer to any social institution or mechanism that exists beyond the immediate family and exercises a degree of voluntary compliance. It is a broad term that can include, for example, clans and notions of kinship, chiefs and customary leaders, aid agencies, police, military personnel, peacekeepers, business enterprises, worker associations, religious beliefs and organisations, civil society groups, vigilantes, local healers, medical staff in clinics or running public health programmes, opinion setters on the media, militia commanders, civil servants, locally elected councils, members of parliament – as well as, sometimes, presidents and ideas about national identity. These authorities are particularly relevant in much of Sub-Saharan Africa, where claims about public authority, and the connections between public authorities and the practice of governance are persistently negotiated and can be fiercely contested.

Thus, public authority is a notion that helps free our research from problematic and misleading assumptions and projections about the nature of statehood, formal authority and formal governance. In the locations in which CPAID will research, actual public authority is mostly made up of informal, semi-formal or ‘twilight’ institutions, including those associated with rebel groups, border trade networks and diverse international actors. Even where the state is present, its manifestations are often unrecognisable as such, or deeply and complexly hybridised.’

Based on previous LSE research, CPAID is kicking off with 3 particular ways of understanding Public Authority:

Based on previous LSE research, CPAID is kicking off with 3 particular ways of understanding Public Authority:

‘The political marketplace – a concept developed by CPAID member Alex de Waal – refers to transactional politics whereby political loyalties and political services are exchanged for material reward. This is an updated, internationally integrated form of patrimonial politics that competes with, and often displaces, processes of state-building and institutional development. The political marketplace is measured and instrumentalised using the ‘political budget’, ‘the price of loyalty’, barriers to market entry and other regulatory elements, and the political-business models and skills of politicians. While monetized politics are found everywhere, in certain places the political market is the dominant logic of the exercise of power, with institutions reduced to a subordinate role. Political markets are increasingly regionalized. Political markets can be turbulent, violent and are integrated into regional and global networks of power and money. New policies and laws may present themselves as protecting the poor while enabling elite and foreign capture of resources.

Recently, new forms of public authority have emerged in countries such as Rwanda and Ethiopia, which exhibit both patrimonial characteristics and long-term developmental aspirations. A growing number of political economists have used the foundational work of Mushtaq Khan to argue that in such countries, the political marketplace plays an important role in driving economic development.

Moral populism – the demonising of the ‘other’, or the glorification of exclusive groups or their beliefs and practices, is a further essential tool in the analysis of movements and shifts in public authority in both state and non-state institutions. Moral populism may be benign. For example, moral populism may be integral to authority in religious organisations, enhancing a sense of community among followers, and people may be attracted to faith-based political scripts in reaction to violent repression. Extremist forms of

OECD axes of fragility

moral populism may also emerge in communities that are subject to severe violence and/or poverty, societal pressure or rapid change, or where many people are traumatized. We identify militant Islamism movements and organizations as manifestations of moral populism, usefully analysed with this lens. Previous research by the CPAID team has described in detail how forms of moral populism can suddenly trigger collective violence or mass flight when linked to moral panics (i.e. when there is a widespread view that people are under immediate threat from evil forces). Moral panics can be of an ethnic nature, but often can be linked to perceptions about things such as witchcraft, child sacrifice and satanic practices.

Public mutuality – In many African contexts, the only real protection available to the rural poor is membership of a locally regulated moral community. More often than not, that moral community requires the vigorous exclusion of outsiders and sometimes violent forms of moral populism. A sense of mutuality is sustained in a context in which politics are attuned to conditions of persistent uncertainty, conflict and trauma. We seek to identify whether and how affected people are cultivating more inclusionary forms of mutuality and seeking to make them ‘public’, including by promoting principles such as integrity and civility in public authority, despite the extreme pressures. Public mutuality includes practices that sustain integrity, trust, civility, inclusion and dialogue, and non- violence.’

Which all sounds absolutely fascinating. Not exactly sure what my role will be yet, but I’m hoping it will include plenty of conversations with communities about how power and public authority actually work, linking up to Oxfam’s work in these places. Over the next couple of decades, the aid world will increasingly zero in on fragile and conflict settings – the toughest nut to crack in development terms, so the sooner we start to understand what life, power and politics there is really like (rather than what we would like it to be), the better. Watch this space.

May 22, 2017

Draft Paper on Adaptive Management in Oxfam – all comments welcome

With a few important exceptions, large international NGOs have been pretty absent from the global conversation about ‘Doing  Development Differently’, but are they doing it anyway and just skipping the meetings?

Development Differently’, but are they doing it anyway and just skipping the meetings?

To find out, a group of LSE Masters Students analysed a bunch of case studies of Oxfam programmes claiming to pursue ‘adaptive management’ approaches. Their report is so interesting that we want to publish it, but first we’re inviting you to comment on their draft, here. Deadline for comments 16th June to g.maneo[at]lse.ac.uk.

The students – Annika Schlingheider, Erica Pellfolk, Gabriele Maneo, and Harsh Desai – analysed seven Oxfam programmes, along with other examples from across the aid business. Here’s the exec sum:

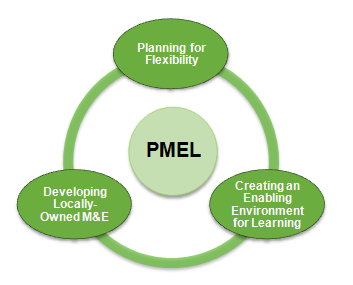

Adaptive management is at the heart of ‘doing development differently’. Whether it is ‘here to stay’ depends on how much it is mainstreamed into existing development programming, especially planning, monitoring, evaluation, and learning (PMEL) cycles. In this report, we find that mainstreaming adaptive management in PMEL involves three strategies: (1) planning for flexibility; (2) developing locally-owned M&E; and (3) creating an enabling environment for learning. Adopting these strategies  contributes to virtuous cycles of PMEL.

contributes to virtuous cycles of PMEL.

Oxfam GB has a broad impact and has long been committed to flexible programming. We thus identify and assess examples of adaptive management within Oxfam’s PMEL frameworks, illustrating enablers and barriers in seven Oxfam programmes. We also showcase examples in Mercy Corps, the World Bank, DFID, and Care International. In doing so, we hope to inform adaptive approaches for PMEL and help practitioners be better equipped to address modern, complex challenges.

Recommendations

Plan for Flexibility Experiment with evolutionary approaches. When outcomes are unclear, implementing parallel pilots may help fine-tune programme design. Though this can be time- and resource-intensive, deliberations that align stakeholder understandings and promote buy-in can offset downsides (e.g. resource-drain) of trial-and-error approaches.

Negotiate flexible funding. Sharing of budget targets, setting up centralised ‘rainy day’ funds for need-based adjustments, and innovating PbR contracts by including early grant funding are three strategies to create conditions for adaptation. If donors are reluctant, inviting them to on-site visits and learning events can familiarise them with programmes, build trust-based relationships, and improve chances for flexible funding arrangements. Training staff to understand flexible budgets is key to such approaches.

Design adaptive logframes and contracts. Logframes are important tools for accountability but often create path dependency. Though donors are interested in adaptive arrangements, they may lack the capacity or knowledge to create them. Negotiating broad-but-defined indicators and incorporating room for adjustments can help build this capacity and prevent lock-in amid changing circumstances. If donors resist adaptive frameworks, it may help to communicate how building-in flexibility during planning can offset the transaction costs of adjusting during implementation.

Develop Locally-owned M&E

Invest in training. Broadening data literacy among country staff allows burden-sharing for M&E and improves capacity to collect timely data. Building capacity is costly initially but can prevent overburdening M&E staff down the road.

Improve partner selection strategies. Selecting partners that are aligned in mandates and resources can (a) help compensate for resource shortages; (b) encourage sensitivity to context; (c) strategically broaden an organisation’s field networks; and (d) align incentives for sustained engagement and communication. It can also create an ‘institutional legacy’ of a programme that enables its long-term resilience.

Foster bottom-up decision-making and data-collection. Encouraging bottom-up tools and approaches (e.g. the Concept Note System and steering committees) can help foster feedback and delegate decisions to local staff and communities. Not only does this reduce transaction costs of top-down management, but it also promotes locally-responsive solutions.

Create an Enabling Environment for Learning

Facilitate communication between country offices. Relying too much on HQ to broker communication can create information siloes. Country staff can take ownership of this process by initiating dialogue with other country offices, especially through events or on-site visits. This has the added benefit of creating alternative sources of institutional memory within the organisation.

Face-to-face dialogue is key. Though webinars and reports are helpful conversation-starters, nothing beats face-to-face communication via learning events, workshops, and in-person visits. Setting aside funding – whether through centralised funds or integrating it into overhead costs – is a first step to mobilise momentum for such events. By creating room for discussions, they allow staff to reflect upon and internalise lessons.

Shift mindsets, not just practices. Being adaptive is intimidating. Investing in coaching and mentoring, and prioritising learning and reflection among younger staff, helps overcome mental barriers to adopting adaptive approaches. Despite high up-front costs, such strategies build organisational culture and resilience for adaptive management.

And here are the case studies.

Within Oxfam

Chukua Hatua(DFID)

A governance programme to strengthen civil society in Tanzania.

GRAISEA

(Sida)

A multi-country programme (MCP) to promote gender-inclusive agri-business in South East Asia.

MRMV

(Sida)

A MCP in eight countries to support rights-based approaches to health and education for citizens.

REE-CALL

(DFID)

A programme in Bangladesh to support economic empowerment, adaptation to climate change, leadership, and learning.

South Caucasus

(European Commission)

A programme in Georgia and Armenia to foster farmers’ rights and promote food security.

SWIFT

(DFID)

A programme in the DRC and Kenya to provide sustainable water, sanitation, and hygiene to citizens.

WWS

(DFID)

A MCP in Afghanistan, Occupied Palestinian Territories/Israel, South Sudan, and the DRC to promote accountable governance by building civil society capacity.

Outside Oxfam

LASER | KPMG & LDP(DFID)

A MCP to strengthen legal and judicial capacity and improve the investment climate in eight countries.

IGP-PSCM | World Bank(World Bank)

A programme in Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda to improve governance in the pharmaceutical sector and broaden access to medicine.

SOMGEP | CARE(DFID)

A programme in Somalia to improve access to and shift norms regarding girls’ education.

PRIME | Mercy Corps(USAID)

A programme in Ethiopia to broaden pastoralist market integration and improve climate change resilience

Over to you…..

May 21, 2017

Links I Liked

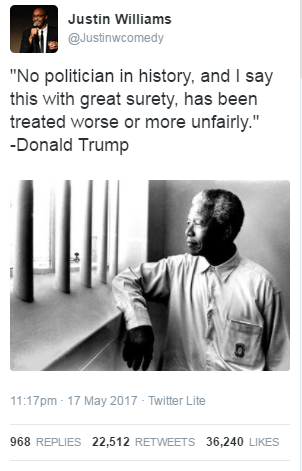

You really need to be on twitter to appreciate the daily soap opera that is US politics. Here are two tweets that went viral in response to the president’s claim of extreme persecution. Wonderful.

You really need to be on twitter to appreciate the daily soap opera that is US politics. Here are two tweets that went viral in response to the president’s claim of extreme persecution. Wonderful.

Enough of twitter – back to ‘long reads’ (800 words or so). A brilliant idea from DFID’s Pete Vowles. We should all write personal user manuals to help colleagues work with us. But how honest are we supposed to be?

CGD’s Bill Savedoff continues his one man crusade against tobacco with some extraordinary (and literal) killer facts’. The drug will kill 200m people this Century. Each death generates about $10,000 in profits for the tobacco industry. The harm hits poor people the hardest

Top geek Lant Pritchett praises y-axis thinking (broad theory) in development economics and ridicules x-axis (specific interventions like the much-hyped RCTs – Randomized Controlled Trials)

Sorry, can’t stay away from POTUS and the quite brilliant piece from David Brooks on Trump ‘a guy whose thoughts are often just six fireflies beeping in a jar’

Sign her up Oxfam India! ‘Mastanamma doesn’t have a birth certificate to prove her 106 years but has millions of followers who can’t have enough of her recipes and Granny Wisdom’ [h/t Mary Matheson]

May 18, 2017

Street Spirit, an anthology of protest that both moved me to tears and really bugged me

Street Spirit: the Power of Protest and Mischief, by Steve Crawshaw is a book that left me deeply confused. As I read it on a recent train ride, I experienced an

Subverting riot police at the G7 in Germany, 2007

alarming level of cognitive dissonance. The uplifting stories of resistance, courage, uprising, revolution etc moved me to tears (something I can best describe as ‘political crying’ – awkward in public places). At the same time, my wonk-mind was shouting ‘how do we know any of these claims are true?’ More on that below.

First, the content. Street Spirit is a coffee-table anthology for trouble makers: thick, glossy paper, lots of photos, and 50 vivid 2-page vignettes of protest and demonstrations from around the world. Feelgood guaranteed (if protest is your bag).

Crawshaw definitely has the T-shirt as a protest connoisseur, with a track record as a senior figure in Amnesty and Human Rights Watch, and a journalist who reported on the Eastern European revolutions and the Balkan Wars. He co-authored a similar collection, ‘Small Acts of Resistance’ in 2010 – in many ways this is an updated, glossier (and shorter) version. It also reminded me of (and quotes) Srjdja Popovic’s wonderful book, Blueprint for Revolution.

Chapters cluster the vignettes into broad themes: passive protesting, using very small actions, confronting violence, the use of humour, satire and the arts. There is a treasure trove of tactics that any activist can mine – holding up mirrors in the Ukraine protests, so the police could see what they looked like (many then swapped sides); ironically applauding the President of Belarus at the same time every week, until the government ending up banning clapping. The endless creativity, humour and courage of activism is indeed deeply moving.

But don’t read this book expecting a dispassionate weighing up of the strengths and weaknesses of different tactics, or the interaction between protest movements and formal political processes. Crawshaw is in the myth-making game (Alex Evans would approve), creating a narrative that moves people to action.

But don’t read this book expecting a dispassionate weighing up of the strengths and weaknesses of different tactics, or the interaction between protest movements and formal political processes. Crawshaw is in the myth-making game (Alex Evans would approve), creating a narrative that moves people to action.

So, even as I choked back the tears, I was annoyed at being emotionally manipulated and stroppily asking, ‘what about selection bias (he makes the valid point that those in authority can seldom envisage change until it happens, but only talks about the protests that he says succeeded)? What about attribution (the books is full of highly questionable sentences along the lines of ‘this protest happened and five years later the government fell’ – how do we know that Kiev police swapped sides because of seeing themselves in mirrors rather than something else?) Even if a protest is successful, what about what happens next – can we really portray Egypt as an inspiring example given what has happened since protests helped overthrow Mubarak? I’m sure a lot of the activists in these pages had sophisticated theories of change, and I wanted to hear about them. No chance.

Which all highlighted for me the dilemmas around following Alex Evans’ advice, getting less nerdy and learning how to build narratives (myths) that speak to people’s hearts and underlying moral and normative frameworks. I worry that the professionalization of Advocacy and Campaigning (of which I guess I am part) has taken us in the other direction, and I think Alex is onto something. But if that’s true, and is exactly what Crawshaw is doing, why do I feel so uncomfortable?

It’s partly because filling the myth gap does not sit easily with recognizing the importance of systems thinking and complexity. Myths require simple Robin Hood narratives. Good v Bad. A → B. ‘Speaking Truth to Power’. Myths don’t go in for nuance, ambiguity and self doubt, which is exactly what’s required if you care about systems and (in my book) truth.

One way to reconcile the tension is by audience – ‘oh don’t worry, the myths are just for the public, but the wonks and campaign insiders need to get complex’. But that feels deeply patronising and/or manipulative, and anyway, you can’t ringfence messages and audiences like that any more (if you ever could).

OK, OK, I’m a navel-gazing killjoy, I’m sorry. Final recommendation? We all need a bit of a boost right now, so read this book and laugh and cry, but please don’t ignore the critical voice in your head that keeps on asking questions that the book doesn’t even try to answer.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers