Duncan Green's Blog, page 119

May 4, 2017

Life in a time of Food Price Volatility: 4 years of research in a 4 page infographic

IDS and Oxfam have put together a snazzy infographic/executive summary of their four year research project, with links to the main documents for those old fashioned enough to want to read something. What do you think of the format?

May 3, 2017

Why is so little being done to stop traffic killing 1.25m people per year, and costing 3% of global GDP? Good new paper.

Part of my purpose in life is to puff good new papers from the ODI, and it’s been a while, so here goes.

Work in the aid business and you regularly hear grisly tales of deaths, injuries and near misses of colleagues and partners on the roads of the developing world. In Peru, I once had the disorienting experience of seeing the rear wheel of my jeep bouncing ahead of us into the night, ending up in Lake Titicaca (the wheel, that is, not me). But the carnage from Road Traffic Accidents (RTAs) is much worse for poor people, communities and children.

The issues has been recognized in the SDGs, which may or may not make any difference – I’m a sceptic, and if you want to find out more, check out an excellent new literature review by Joseph Wales at the ODI. Some excerpts;

‘Road safety is a major international health issue, but one that rarely receives the attention it merits. Every year, an estimated 1.25 million people are killed on the world’s roads and up to 50 million people incur non-fatal injuries. This makes road traffic collisions the ninth leading cause of death across all age groups globally and the main cause of death among those aged 15-29 years. On current trends, collisions will become an even more prominent global health challenge, rising to become the seventh leading cause of death by 2030.

Some 90% of road traffic fatalities occur in low- and middle-income countries, where pedestrians, cyclists and motorcyclists make up the bulk of those affected. Working age males make up a large proportion of those killed and injured; but children, adolescents and the elderly are also disproportionately affected in many contexts. The effects of road traffic collisions are particularly felt by households from poorer socio-economic groups. They are both more likely to have a member fall victim to a collision and less able to bear the considerable costs of a funeral, medical treatment and lost income resulting from extended periods of recovery or permanent disability. For some households, the loss or injury of a member in a road traffic collision can be the difference between financial stability and poverty. At a national level, the economic costs of road traffic collisions alone are substantial – estimated at 5% of gross domestic product (GDP) in low- and middle-income countries, and totalling up to 3% of global GDP. The estimated costs of initiatives to improve road safety are dwarfed by the scale of economic and social damage currently caused by road traffic collisions.

Historically, initiatives to improve road safety have often been structured around the collision itself. Broadly, initiatives aimed to either (i) reduce the incidence of collisions; or (ii) reduce the severity of collisions – generally with a strong focus on changing user behaviour – whether through public information campaigns (e.g. on drink driving), legislation (e.g. speed limits) or the physical road infrastructure (e.g. speed bumps). However, there has been increased recognition that the immediate causes of road traffic collisions, fatalities and injuries cannot be viewed in isolation from each other or the broader context, and that combinations of interventions demonstrate greater cost-effectiveness. This has resulted in a growing focus on system level issues and the use of simultaneous interventions at multiple levels to address the causes of road traffic collisions in an integrated and coherent manner. The ‘Safe Systems’ approach that underlies the UN Decade of Action for Road Safety (2011-20) is based on this broader understanding of how to improve road safety.

Interventions to reduce road traffic collisions, deaths and fatalities are therefore broad and involve initiatives that focus not only on roads and road design, but other issues within the broader transport system and beyond. These can be broadly divided into five groups:

Interventions to reduce road traffic collisions, deaths and fatalities are therefore broad and involve initiatives that focus not only on roads and road design, but other issues within the broader transport system and beyond. These can be broadly divided into five groups:

Improvements in land use and the built environment (e.g. land zoning, traffic calming measures, cycle paths)

Improvements in education, legislation and enforcement of traffic regulations (e.g. speed limits, advertising public campaigns to reduce drink driving)

Improved vehicle and safety standards (e.g. regulations on manufacturing standards, compulsory safety features)

Improved availability and quality of public transport

Improved post-collision emergency response and care

This shift towards a ‘Safe Systems’ approach has also helped to highlight the importance of politics and state capacity to the successful creation and implementation of road safety policies. Successful implementation requires political momentum to initiate a range of policies to promote road safety, but also the enforcement of regulations and laws carried out in practice, as well as coherent and coordinated action between the different agencies and organisations at national and local level that have influence over road safety. This approach requires improving the functionality and coordination of a wide range of actors and so the task is of a different order than more traditional, technical interventions. There is strong empirical evidence that countries with well-functioning and capable state institutions experience lower levels of road traffic collisions, deaths and injuries compared to those that are weaker and less coherent.

The political salience of road safety is generally low, especially when given the high number of deaths due to road traffic collisions. Most interventions have  tended to focus on preventing injuries to vehicle occupants, despite pedestrians being more likely to be victims and to be severely injured or killed. These trends are partly due to many interventions originating in high-income countries where vehicle occupants make up a higher proportion of victims. They are also related to challenges of mobilisation due to collective action and coordination issues, poor data availability and the challenge of attributing causes. This is particularly the case where the individuals involved in collisions may be blamed for causing them, or where there is no clear individual, institution, policy or design feature whose impact or negligence can be mobilised around.’

tended to focus on preventing injuries to vehicle occupants, despite pedestrians being more likely to be victims and to be severely injured or killed. These trends are partly due to many interventions originating in high-income countries where vehicle occupants make up a higher proportion of victims. They are also related to challenges of mobilisation due to collective action and coordination issues, poor data availability and the challenge of attributing causes. This is particularly the case where the individuals involved in collisions may be blamed for causing them, or where there is no clear individual, institution, policy or design feature whose impact or negligence can be mobilised around.’

My takeaways from this are that RTAs act as a lens on the modern world, highlighting issues of power, inequality, and the importance of thinking about systems, not just linear interventions. And that the lack of attention to something that costs this much, and is readily easy to address, is unforgiveable.

What might help take this forward is to dig into the politics a lot more – what would a power analysis of RTAs look like? Who are the likely blockers as well as the drivers of reform?

In terms of building a campaign around this, you would think a building a cross class coalition would be pretty straightforward, since rich people as well as poor get mown over by drunk drivers and the rest. But are there high profile villains that could galvanize a public campaign? Urban developers refusing to invest in safety measures? Booze firms blocking breathalysers? Car companies? What are the successes we can learn from, like the Good Samaritans movement in India?

Here’s the UN Decade video, starring Kevin Watkins

May 2, 2017

Social Accountability from the Trenches: 6 Critical Reflections

Guest post by Gopa Kumar Thampi of The Asia Foundation

There is a clearly a surge in social accountability initiatives across the globe today. From informal expressions at the grassroots to entrenched voices in  corridors of power, the social accountability multiverse has become stronger and diverse. It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that we are indeed witnessing the rise of an ‘audit society’ that animates the spectrum between confrontation and collaboration in citizen’s engagement with the state. The proliferation of toolkits and manuals embellishes this trend as social audits and scorecards have become commonplace parlance for civic activists, policy wonks and academics as they line up an impressive array of data to hold the state to account. However, viewed from the trenches of day-to-day encounters with social accountability, some notes of caution need to be flagged:

corridors of power, the social accountability multiverse has become stronger and diverse. It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that we are indeed witnessing the rise of an ‘audit society’ that animates the spectrum between confrontation and collaboration in citizen’s engagement with the state. The proliferation of toolkits and manuals embellishes this trend as social audits and scorecards have become commonplace parlance for civic activists, policy wonks and academics as they line up an impressive array of data to hold the state to account. However, viewed from the trenches of day-to-day encounters with social accountability, some notes of caution need to be flagged:

1) Primacy of technique over politics: ‘Bring politics back’ is an oft-quoted plea that is heard at the closure of every learning and sharing event on social accountability. Though some excellent conceptual writings exist on the rationale and approaches to acknowledge politics, there is clearly a knowledge gap on praxis. This gap becomes accentuated when projects finish their shelf lives and local interlocutors are left dealing with unplanned political aftermaths. What we need is not just the ‘why’ and ‘what’ of navigating politics, but the ‘how’ too. There is also the bias of working with executive ‘accelerators’ – reformist executives who push the frontiers of constructive engagement and deliver high quality impacts on pilot projects. But the reason why these ripples of change never result in a transformative wave is because politics is often viewed as a problem best avoided. We need to acknowledge that any change sans the inconvenience of politics is bound to be short lived. Working with politics and programming with sensitivity to political ecologies means more flexibility in design and implementation. This is where contemporary discourses on ‘Doing Development Differently’ are opening up new opportunities and pathways.

2) Tyranny of tools: Social Accountability tools like public hearings, scorecards, report cards and social audits have played a major role in bringing rigor to discourse and praxis, by moving the frame of reference from the anecdotal to the evidential. However, projects driven by the novelty of applying tools run the risk of not just undermining sustainable impacts, but paving the way for a far more serious erosion of trust and acceptance. Tools have a tendency to trade efficiency over inclusion, and participation over representation. There is also a case for ensuring quality. As an evolving field where theory consistently lags behind practice, it is critical that the field of practices is constantly reviewed, reflected upon and improved. Finally, there is the issue of local capacities. Applications of tools in rural areas often rely on external agents to play the role of interlocutors, but seldom do legacies and capacities get left behind for continued actions by local interlocutors.

2) Tyranny of tools: Social Accountability tools like public hearings, scorecards, report cards and social audits have played a major role in bringing rigor to discourse and praxis, by moving the frame of reference from the anecdotal to the evidential. However, projects driven by the novelty of applying tools run the risk of not just undermining sustainable impacts, but paving the way for a far more serious erosion of trust and acceptance. Tools have a tendency to trade efficiency over inclusion, and participation over representation. There is also a case for ensuring quality. As an evolving field where theory consistently lags behind practice, it is critical that the field of practices is constantly reviewed, reflected upon and improved. Finally, there is the issue of local capacities. Applications of tools in rural areas often rely on external agents to play the role of interlocutors, but seldom do legacies and capacities get left behind for continued actions by local interlocutors.

3) Interrogating civil society: A dominant theme in the discourse and praxis of accountability is the emphasis placed on the role of civil society as the vanguard of change. There are genuine concerns that the sector is fast losing its rootedness and legitimacy –a schism grows between genuine informal social movements and formal organized civil society. One, exhibiting the vigor of confronting and embracing the politics of governance and the other, seen as obsessed with the rigor of getting the method right. We need to honestly interrogate our understanding of civil society organizations and widen our focus to bring in new, unseen but genuine champions from the cutting edges. A considerable proportion of existing civil society proponents of accountability often tend to be urban centered, and speak a language that appeal to our funding imperatives. We need to empower and enrich the language that has the credibility and endorsement of the basic constituency that we seek to address – citizens, especially the disadvantaged.

4) Seduction of contestation: Rights-based social mobilization sometimes leads to an unintended consequence – spiraling expectations. When amplified  voice encounters weak responses from the state, ‘rude accountability’ manifests. The grammar of engagement changes swiftly to a confrontational mode. In social contexts where power asymmetries are accentuated, these confrontations can take very violent forms. There is a case for calibrating social accountability initiatives to match state capacity. In contexts marked by a trust deficit between state and citizens, it may be prudent to focus on trust building exercises as a starting point. The other issue is of public dissemination. Should one go for a big bang release of the findings from a social audit, thereby securing a guaranteed news coverage? Or, should the state be allowed to frame its responses and then go public with the findings and responses? To strengthen principles of constructive engagement, closing the feedback loop in the public domain becomes a critical factor. Voice needs an ear to respond.

voice encounters weak responses from the state, ‘rude accountability’ manifests. The grammar of engagement changes swiftly to a confrontational mode. In social contexts where power asymmetries are accentuated, these confrontations can take very violent forms. There is a case for calibrating social accountability initiatives to match state capacity. In contexts marked by a trust deficit between state and citizens, it may be prudent to focus on trust building exercises as a starting point. The other issue is of public dissemination. Should one go for a big bang release of the findings from a social audit, thereby securing a guaranteed news coverage? Or, should the state be allowed to frame its responses and then go public with the findings and responses? To strengthen principles of constructive engagement, closing the feedback loop in the public domain becomes a critical factor. Voice needs an ear to respond.

5) Rethinking evaluation: It is near impossible to engineer transformative changes given the short project cycles of social accountability initiatives . End of project evaluations can seldom provide meaningful insights. What the field of social accountability needs are longitudinal studies that explore questions related to sustainability and uptake of reported successes. In particular, five aspects could be emphasized: (a) Extent of multi stakeholder engagement; (b) Width of citizen involvement, especially aspects of inclusion; (c) Long-term partnership among stakeholders; (d) Legal or institutional recognition of civil society engagement; and (e) Extent to which processes generate compliance and provide deterrence. Rather than focus on narrowly defined outcomes, evaluations should dwell into process indicators that reveal if critical pathways and enablers are set in place.

6) Illiberalism and social polarization: Perhaps the greatest challenge for social accountability initiatives is the growing popularity of illiberal electoral democracies and, in parallel, the deep social polarization that is tearing up fragile social fabrics. Leaders with divisive agendas and populist outlooks, aided by manipulated (and at times, completely fake) news are posing a grave threat to democratic institutions. There is also the distinct disconnect between the informed public and the mass public in terms of their expressed trust in institutions. All these have substantive repercussions on the way we imagine and operationalize social accountability. We need to focus on activities that build bridging social capital – locating actions that result in enhanced inter-group collaboration. The role of traditional media – once the trusted ally and champion for accountability – needs to be evaluated given the ubiquitous spread of social media. Rather than lamenting the loss of old spaces, the strategy should be to appropriate the new ones.

To sign off: Social accountability is recognition that there exists a lack of engagement with the public institutions that are so critical to our daily lives, a lack of influence in decision-making and more importantly, a lack of voice for expressing our needs, concerns and demands. We believe that social accountability approaches enable citizens, especially the voiceless and the powerless, to engage with state institutions in a proactive and constructive way to demand and exact accountability and responsiveness. This moral high ground of the concept and praxis of social accountability needs to be protected and nurtured.

To sign off: Social accountability is recognition that there exists a lack of engagement with the public institutions that are so critical to our daily lives, a lack of influence in decision-making and more importantly, a lack of voice for expressing our needs, concerns and demands. We believe that social accountability approaches enable citizens, especially the voiceless and the powerless, to engage with state institutions in a proactive and constructive way to demand and exact accountability and responsiveness. This moral high ground of the concept and praxis of social accountability needs to be protected and nurtured.

This post originally appeared on the World Bank’s GPSA website. Here’s a video of Gopa haranguing the Bank on this topic at a recent Brown Bag Lunch (his presentation starts at minute 12).

May 1, 2017

Links I Liked

Thomas Hobbes’s final exam paper questions, Magdalen College, Oxford, 1608, h/t Will Davies

The interwebs were buzzing with a brilliant new Ethiopia paper from Chris Blattman and Stefan Dercon: ‘Everything We Knew About Sweatshops Was Wrong‘

According to a World Bank survey of 10,000 influencers in over 40 countries, their top development priority is governance (↑ rapidly in recent years)

Why do some jobs (& their loss) matter politically more than others? Thought-provoking from Paul Krugman

This is England (sort of). Letter in the Telegraph, h/t Stig Abell

This is England (sort of). Letter in the Telegraph, h/t Stig Abell

The US and UK are rapidly diverging on aid policy: Leaked documents shed some light on depressing White House plans; Owen Barder on Theresa May’s welcome decision to stand by 0.7 commitments (after top lobbying from Bill Gates and others). But the UK still indulges in too much magical thinking: As it spends more in fragile and conflict-affected states, DfID’s recorded losses to fraud of only 0.03% of its budget look increasingly unconvincing, say MPs

Satellite images trigger payouts for Kenyan farmers in the grip of drought. Humanitarian insurance rapidly becoming A Thing

70 years is long enough. So it’s happy birthday, Neoliberalism, and farewell. Kate Raworth on a roll with this new Doughnut Economics animation. She also smashed it on Radio 4’s prestigious Start the Week programme (her bit starts at 24m 45s)

April 27, 2017

Guardian launches important new Website on Inequality

The Guardian launched a promising new website on inequality this week, edited by Mike Herd.

‘Over the coming year, the Guardian’s Inequality Project – supported by the Ford Foundation – will try to shed fresh light on these and many more issues of inequality and social unfairness, using in-depth reporting, new academic research and, most importantly, insights from you, our audience, wherever you are in the world and whatever your experiences of inequality.’

It kicked off in geeky style with a discussion of inequality indexes:

‘Measuring comparative levels of global inequality is far from straightforward. Is it fair to focus only on financial inequalities, or should we consider quality of life too? If so, how do you measure it?

There are three key measures of financial inequality: income, consumption and wealth. Usually, the term inequality is used to mean income inequality, as it’s the basis for most measures and the best documented of the three.

But there are compelling arguments for using consumption or wealth too. Consumption often tracks income, as people’s living standards can be understood through what they consume. Wealth, or accumulated capital, can also be a strong determinant of living standards in an increasingly unequal world.

Of course, monetary measures fail to capture inequalities beyond material standards of living. What about equitable access to healthcare and education, or quality of life for women or minorities in certain countries? Here’s a quick guide to some measures of inequality – and how countries compare under them.

The Gini index is the most widely used measure of inequality (see map above). It looks at the distribution of a nation’s income or wealth, where 0 represents complete equality and 100 total inequality. However, it is criticised for being overly sensitive to what happens to people in the middle, and not so good at picking up changes at the extremes, where there has been a growing focus in inequality research.

Using the most recent figures, South Africa, Namibia and Haiti are among the most unequal countries in terms of income distribution – based on the Gini index estimates from the World Bank – while Ukraine, Slovenia and Norway rank as the most equal nations in the world.

The Palma ratio is an alternative to the Gini index, and focuses on the differences between those in the top and bottom income brackets. The ratio takes the  richest 10% of the population’s share of gross national income (GNI) and divides it by the poorest 40% of the population’s share. This measure has become popular as more income inequality research focuses on the growing divide between the richest and poorest in society.

richest 10% of the population’s share of gross national income (GNI) and divides it by the poorest 40% of the population’s share. This measure has become popular as more income inequality research focuses on the growing divide between the richest and poorest in society.

According to the Palma ratio figures in the UN Human Development Index, Ukraine, Norway and Slovenia were the most equal countries to live in when considering distribution of income between the richest and poorest in society. South Africa, Haiti and Botswana had the starkest inequalities in income, based on the Palma ratio.

Living standards inequality

Mixed rankings are based on a range of measures rather than solely focusing on income, wealth or consumption. The idea is to put people’s access to opportunities and sense of well-being at the forefront, and encourage countries to guide their public policies towards making their citizens happier, rather than just increasing GDP.

The World Happiness Report ranks 155 countries from 1 to 10 in terms of happiness, and is based on a survey of 1,000 people from each country. The measure is based on real GDP per capita, social support, healthy life expectancy and people’s perception of their freedom to make life choices, generosity, and perceptions of corruption.

The World Happiness Report ranks 155 countries from 1 to 10 in terms of happiness, and is based on a survey of 1,000 people from each country. The measure is based on real GDP per capita, social support, healthy life expectancy and people’s perception of their freedom to make life choices, generosity, and perceptions of corruption.

In the latest report the Nordic countries lead the way, with Norway, Denmark and Iceland at the top of the list, while the Central African Republic, Burundi and Tanzania lag behind with low scores in GDP per capita, social support and people’s freedom to makes life choices.

However, wealth alone doesn’t bring happiness. According to the figures from the World Happiness Report, a high GDP doesn’t always equate with a high happiness ranking. Qatar, which has the highest contribution from GDP to its happiness ranking, comes in at 35. Likewise, while Hong Kong is in eighth place when it comes to GDP contribution, it only rates 71st in the overall happiness rankings. Norway, the highest ranking in terms of happiness, comes in third in the GDP rankings.’

It’s got some nice visuals too, like this drone video on South Africa’s inequality

To get in touch, email inequality.project@theguardian.com . But it doesn’t seem to have it’s own twitter handle or email subscription yet – cd you fix please, guys?

April 26, 2017

How far has DFID got in implementing ‘Doing Development Differently’ ideas on the ground?

I’ve been banging on about the ‘Doing Development Differently’ movement for a few years now. Initially driven by big bilateral donors frustrated with the  failure rate of old school project approaches, especially in trying to ‘build states’ and reform governments , DDD advocates ‘politically smart and locally led’ approaches, avoiding cookie cutter ‘best practice’, while staying sufficiently aware and adaptive to learn and tweak your interventions as you go.

failure rate of old school project approaches, especially in trying to ‘build states’ and reform governments , DDD advocates ‘politically smart and locally led’ approaches, avoiding cookie cutter ‘best practice’, while staying sufficiently aware and adaptive to learn and tweak your interventions as you go.

But all too often, reform movements such as DDD fizzle out when put into practice. Their initial clarity gets blurred by the demands of ‘rolling out’ to the unconverted; ‘mainstreaming’ dilutes the rigour and translates into just another level of compliance and set of tickboxes for staff and partners.

Is that happening to DDD? To find out, ODI researchers supported DFID’s attempts to DDD throughout 2016, both at head office, and in country programmes in Malawi, Rwanda, Tanzania and Nepal. They have now written up what they saw in a new report, by Leni Wild, David Booth and Craig Valters. Some of the findings that struck me include:

‘DFID’s growing emphasis on being ‘problem driven’ – setting aside standard formulas and templates and focusing instead on specific constraints to development that need to be unlocked to enable progress. There is often an emphasis on facilitation or convening local efforts, and on being politically smart in critical areas such as inclusive economic development.

Less encouragingly, it has proved easier for staff to build-in an ability to respond to changes in context, than to set out an approach that commits to purposeful experimentation or ‘learning by doing’. While there are a few good examples of facilitation of locally-led change, this also remains a challenging dimension.’

In terms of my current favourite 2×2 (left), that means DFID is more comfortable above the horizontal axis, than below: it is easier to admit uncertainty on context than on intervention.

Getting faster at failing (and stopping): ‘Take action to scale back funding where there are early signs of failure. As well as being better ‘value for money’ for UK aid, it also achieves real results.’

On Why Now? ‘Adaptive management is among other things, a response to the retreat from budget support that has occurred over the last few years, and the return to donor country operations that consist of a portfolio of projects or programmes.’

On Fragile States: ‘It is unclear that much headway has been made in applying flexible or adaptive approaches in conflict-affected countries.’, partly because the role of other departments on issues like counter-terrorism means that ‘consensus across government is more likely to be achieved by falling back on standard ‘train and equip’ programmes, for instance around security and justice sector reform.’

A missing link to gender work: Adaptive and gender programming have much to learn from each other but so far ‘Gender programmes have a tendency to fall back on ‘best practice’ rather than ‘best fit’ or locally-appropriate approaches: it remains rare for gender-related programmes to use structured experimentation to test different possible ways of empowering women and girls and to adapt their approach based on learning about which programme activities work more or less well.’

The backroom people aren’t the problem after all: ‘In our experience, procurement staff can be among the champions of innovative programme design, despite common perceptions to the contrary.’

Portfolios not projects: The report advocates thinking in portfolios rather than individual projects, which would allow

‘Obtaining a balanced mix of programmes that are adaptive and non-adaptive in a given sector or country portfolio: This could help in managing concerns that adaptive programmes can have high staff costs and unpredictable spending rates, and could support synergies between programmes that are more or less adaptive.

Experimentation with a range of interventions to address a common problem: This would allow for a ‘multiple bets’ approach, helping to manage risk and create space for complementarities and learning across different implementing partners.’

All in all, a useful reality check. Hope ODI can continue to shadow DFID as the DDD work matures. Has anyone done anything similar on other donors by the way?

For info, now I have more or less finished promoting the book, I’m moving on to doing some research on how aid donors (both INGOs and bilateral) work in fragile contexts, both in terms of promoting social and political action, and in working with non-state forms of ‘public authority’ in Africa. When plans become clearer, I’ll be coming back to you to ask for reading, contacts and advice.

April 25, 2017

Pragmatism and its discontents: Brian Levy’s brilliant review essay on How Change Happens

Brian Levy, governance guru and author of Working with the Grain, recently published this magisterial essay on his blog. Nominally a review of How  Change Happens (chuffed, naturally), it goes way beyond to provide a powerful critique of the aid/development/progressive consensus in light of the events of the last year. Enjoy.

Change Happens (chuffed, naturally), it goes way beyond to provide a powerful critique of the aid/development/progressive consensus in light of the events of the last year. Enjoy.

At times in the last few years”, writes Duncan Green in his recent book How Change Happens, “it has felt like something of a unified field theory of development is emerging”. As Hegel reminded us, however, the owl of wisdom flies at dusk. As recently as early 2016 (which is about when he wrote these words) Green’s exuberant enthusiasm was shared by many of us. But a year, we now know, can be an eternity.

How Change Happens synthesizes a growing body of work that has aimed to move development scholarship and practice away from a pre-occupation with so-called ‘best practice’ solutions. It captures well the sensibility of the new literature – a paradoxical combination of the enthusiasm of a breakthrough and the pragmatism of seasoned practitioners who have learned the limitations of over-reach, often through bitter experience. But, as per Hegel, has our quest for useful insight reached its destination only to find that a new journey has begun, a different and more difficult journey than the one we had planned?

In this review essay, I use the insights of How Change Happens to explore this question. I unbundle into two broad groups the categories of analysis Green uses to delineate the grand unified theory. In discussing the first group, I highlight what we got right about the drivers of change; in discussing the second, what we got wrong. I then suggest possible ways forward.

Dancing with the system

Change, Green suggests, can be understood as shaped by interactions between power, complexity and agency:

Power: Green builds on a ‘four powers’ model: ‘power within; power with; power to; and power over’. “A power analysis tells us who holds what power relative to the matter, and what might influence them to change…. Understanding how formal and informal power is distributed, and how that distribution shifts over time are essential tasks for any activist intent on making change happen.” (p.95).

Power: Green builds on a ‘four powers’ model: ‘power within; power with; power to; and power over’. “A power analysis tells us who holds what power relative to the matter, and what might influence them to change…. Understanding how formal and informal power is distributed, and how that distribution shifts over time are essential tasks for any activist intent on making change happen.” (p.95).

Complexity: “In complex systems, change results from the interplay of many diverse and inter-related factors…. Because of the number of relationships and feedback loops, they cannot be reduced to simple chains of cause and effect.”

Agency, encompassing grassroots citizen activism, advocacy, and leaders, with “leaders [at all levels] central to any understanding of how change happens….[They] operate at the interface between structure and agency”. (p. 199)

To link these, Green uses the metaphor of learning to ‘dance with the system’: “Understanding how the state in question evolved, how its decisions are made, how formal and informal power is distributed within it, and how distribution shifts over time – are essential tasks for any activist intent on making change happen.” (p.95).

Insights along the lines of the above have led many of us to adopt a pragmatic approach to policymaking and implementation. In the spirit of working with the grain, of doing development differently, of problem-driven iterative adaptation, of politically smart, locally-led development (I list these buzzwords to signal who I mean in this essay when I speak of “we”), we focused on incremental change — pursuing quite modest gains to address very specific problems, and taking much of the prevailing configuration of power and institutions as given, as constraints on what is achievable. We justified incrementalism along these lines as a way of achieving development gains that were valuable in themselves – and, perhaps, might also be catalysts for a cascade of subsequent opportunities. And then, our pragmatism notwithstanding, we were mugged by reality.

Blind spots

Suddenly and unexpectedly we find ourselves in a different world, the world of Donald Trump and Brexit, a world with democracy seemingly in retreat in many, many countries, a world where many of the foundational presumptions of the turn to pragmatism can no longer be taken for granted. Blindsided by change we must ask: what did we get wrong in the way we danced with the system? This brings us to Green’s second group of analytical categories – state institutions, political parties, and norms.

To begin with state institutions, “the unsung heroes in the drama of development”, Green suggests, “(are) civil servants who soldier on despite the obstacles, because the stakes are so high – the institution they work within will shape the fates and futures of their peoples. That institution is the state.” (p.79). But the distinctive political, economic and social contexts within which state institutions are embedded constrain technocratic efforts to improve their performance. Many of us responded to this messy complexity by embracing the incremental, problem-driven approach described above. We lulled ourselves into taking a very constricted view of the power (for good and ill) of state institutions.

Political parties were similarly neglected. As Green notes, “development thinkers pay political parties scant attention, and aid organizations tend to discount

their importance. But, however dull…they are the clutch in the engine of politics, linking citizens to government…[and] carry the potential to achieve changes on an otherwise impossible scale.” (p.113)

India’s National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme, in what was for me the most compelling example in a book filled with rich examples, illustrates powerfully the difference that political parties can make.

“India’s landmark 2005 National Rural Employee Guarantee Act (NREGA), which guarantees all citizens 100 days of unskilled employment per year on public works programmes, came about due to a combination of determined citizen activism and the fortunes of the Congress Party”. (p.125) By 2015, the NREGA gave employment to 122 million poor people across India. (p. 126). (Read that last sentence twice!!!) Congress embraced the NREGA in 2004 at a time when, the idea had been developed by civil society, and Congress “needed to rapidly cobble together a programme”…and after “a determined campaign involving a fifty-day march across the country’s poorest districts, sit-in protests, direct contacts with politicians, and public hearings.” If Congress had not won the 2004 elections, “the NREGA might well have joined the ranks of good, but failed, civil society initiatives”. (p.126)

Our engagement with norms, the final analytical category in this group, was even more problematic. “Empathy is critical” Green notes, “if we are to build a bridge to people who see the world very differently from ourselves….” (p.221). However, “we tend to default to working with ‘people like us’, when alliances with unusual suspects can be more effective”. But focusing on norms isn’t only necessary as a way of being more effective in building progressive coalitions. As Green notes (in a moment of prescience, but which reads as something of an aside, out of step with the generally optimistic tone of the book), “the prospect of norm shifts can provoke a violent backlash”. (p. 61) Indeed, it can.

Here, bringing the above pieces together, is what I think happened: While we were looking elsewhere, made complacent perhaps by our conviction that we were on the side of the justice towards which the moral universe was bending, we allowed ourselves to be trumped. We ignored the rising counter-reaction – the pushback of powerful (and monied!) interests, the resentment of those whose relative (though not necessarily absolute) standing was being undercut by a changing world, the growing resistance to a progressive (in our terms) change in norms. Crucially, we lost sight of the dynamics of power – specifically of the power of political parties to mobilize on the basis of ideas and incentives which we easily dismissed as reactionary. In so doing, we ceded the terrain of contestation over the largest political prize of all — control over state institutions – to actors and ideas which we presumed had been consigned to the dustbin of history.

And then, one bleak morning after another, we awoke to discover that the terrain had shifted radically, that control over state institutions was shifting, and that our hard-won incremental gains risked being washed away by tidal waves of reaction.

What is to be done?

What now? On the surface the task is straightforward: we need to learn from the example of the right. As Green puts it, quoting Milton Friedman, “only a crisis produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions taken depend on the ideas that are lying around”. As we also learn from the right, to be transformational these ideas need to have broad appeal, to be actively incubated within the framework of a large, resurgent political party. (Please, no fringe parties in the name of purity!).

What now? On the surface the task is straightforward: we need to learn from the example of the right. As Green puts it, quoting Milton Friedman, “only a crisis produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions taken depend on the ideas that are lying around”. As we also learn from the right, to be transformational these ideas need to have broad appeal, to be actively incubated within the framework of a large, resurgent political party. (Please, no fringe parties in the name of purity!).

How Change Happens is stimulating and satisfying in the guidance it offers activists as to ‘how’ to pursue their agendas. But (as per the title) it has almost nothing so say about the ‘what’…. (beyond its subtext, which signals clearly that it shares the values and aspirations of ‘people like us’). This focus on the ‘how’ with inattention to the ‘what’ is shared by much of the literature Green synthesizes (my own work included). Indeed, for many of us, it has been a point of principle to redirect attention away from polarized debates about fanciful ends towards pragmatic exploration of means.

But the times require heightened attention to the vision towards which our many localized efforts are directed; we need a new balance between the ‘what’ and the ‘how’. The broad contours of a progressive vision are clear: that we give our lives meaning by embracing inclusion, mutual solidarity, and stewardship as organizing principles for a thriving society – thereby honoring the highest values inherited from our past, and acting on behalf of future, as well as current generations. Easily said, but evidently there is much work to be done to give content to inclusion and stewardship in a way that responds effectively to our brave new world of automation and globalization, and that (as per Green’s admonition vis-à-vis norms) builds bridges to people who see the world very differently from ourselves.

When I speak of a ‘new balance’, I am not suggesting abandoning what we have learned over the past decade about wrestling with the ‘how’ of development. Overcorrection – an endlessly swinging pendulum of fashionable ideas – has long been a chronic, debilitating disease of development theorizing and practice. As I have explored elsewhere, the embrace of pragmatism was itself a response to a decade of democratic hubris. That hubris was disastrous. It set the stage for disappointment, as it became evident that grand promises could not be met. Worse, in failing from the first to acknowledge (and communicate effectively) the messy complexity of democratic governance, hubris laid the groundwork for an attack from the right. It allowed the critics of government to successfully depict the challenging realities of democratic governance as ‘proof’ of the futility of pro-active public policies, of efforts to work collectively to build a better world.

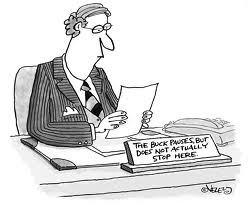

It is easy (and seductive) to preach Manichean visions of perfection and evil. If one has no real interest in governing effectively (or perhaps has a hidden

Not a useful theory of change

interest in undermining and then dismantling prevailing patterns of public governance), then there is no reason to exercise restraint. (Of course, should one then find oneself in power – a la DT; the Republican Party; or the champions of Brexit – then the reality of false promises will become evident, hopefully to be followed by comeuppance and discrediting.) But if the goal genuinely is to leverage collective endeavor and the public sphere as a way to build a better life for all, then the challenge is a more demanding one.

We need to communicate two superficially contradictory ideas at the same time: that embracing a vision of inclusion and stewardship in a thriving society offers a pathway to a fulfilling life – and that the quest to realize that vision will be challenging, fraught with obstacles. In the recent past, we have done neither: we have neglected the ‘what’ in favor of the ‘how. And our work on the ‘how’ has become so pre-occupied with addressing very specific problems that we ceded to ideologues of both the right and the left the terrain of discourse as to how the public sphere works, why, what are reasonable expectations, and it should be engaged.

A way to combine hope and pragmatism in a coherent vision is to underscore that, however challenging and fraught with obstacles, the quest itself can itself be a source of fulfilment. Doing our part; not everything, but enough to inspire a sense of possibility, and thereby successfully pass the baton to the next generation. That, as per the wisdom of ancestors, “it is not for us to complete the task, but neither is it for us to desist from it.”

April 24, 2017

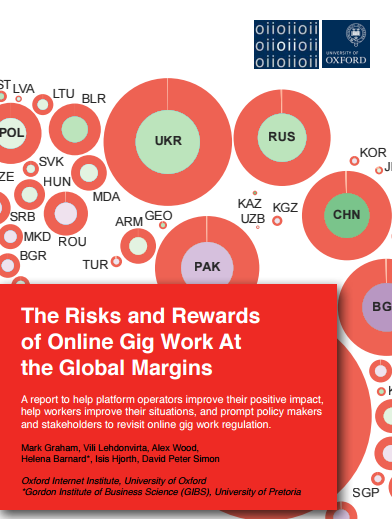

What do we know about ‘online gig work’ in developing countries?

What do we know about ‘online gig work’ in developing countries? Until recently, all I’d read about was the bizarre world of gold farming – gamers in East  Asia (even prisoners in Chinese labour camps) playing to accumulate credits they could then sell on to lazy Western players. A new report from the Oxford Internet Institute filled me in on where the phenomenon has got to.

Asia (even prisoners in Chinese labour camps) playing to accumulate credits they could then sell on to lazy Western players. A new report from the Oxford Internet Institute filled me in on where the phenomenon has got to.

Online gig work is paid work allocated and delivered by way of internet platforms without an explicit or implicit contract for long-term employment. For instance, a job could consist of a temporary graphic design project, which itself might refer to a bundle of Photoshop tasks. These tasks could be any number of different things, including more mundane tasks such as data entry.

To find out how it works, the Oxford researchers ran 150 interviews, and a survey (online, natch) of 450 respondents. They also got access to anonymized data on one major online platform. Here’s what they found:

The commonest form of work is ‘double auction’, where both the worker and the “client” can solicit tasks and quote a price. The industry relies on algorithmic controls — such as ratings and reputation scores and automated tests — to build a ‘reputation rating’ for companies and workers.

These ratings are combined with work history (number of completed jobs, hours worked and total earnings) and test scores in order to rank workers. Clients advertise jobs, then platforms algorithmically filter more tasks towards the highest ranked workers, meaning that those with the best overall reputation are more likely to receive more work. Scores and reputation therefore act as a powerful system of labour control, with both rewards and risks for workers.

The new jobs definitely work for some people; here’s Angel from the Philippines:

Moses

“For me, it’s a high paying job, because now, I was able to afford an apartment, pay my own bills, my own internet connection, my own cable, paying for our own food, for my kids’ milk. That’s all on my own.”

Over half the respondents found the tasks stretching rather than just drudge work. But even the anonymity of online does not prevent discrimination:

‘Moses is a 26-year-old translator from the Nairobi slums who uses a digital gig work platform. He often changes the geographical location listed on his profile, explaining how the platform makes it hard given he’s a Kenyan. He says that identifying clients in gig-based work forces you to constantly realign your profile to fit the job description. As a result, many of Moses’s clients believe that he is based in Australia, just as they are unaware that he is a college dropout rather than a successful translator. The pronounced discriminatory practices Moses is met with means that he is constantly creating a persona in order to be able to win tasks. Moses and others like him say bowing down to discriminatory practices on digital gig work platforms is a commonplace necessity: “You have to create a certain identity that is not you. If you want to survive online you have to do that.”’

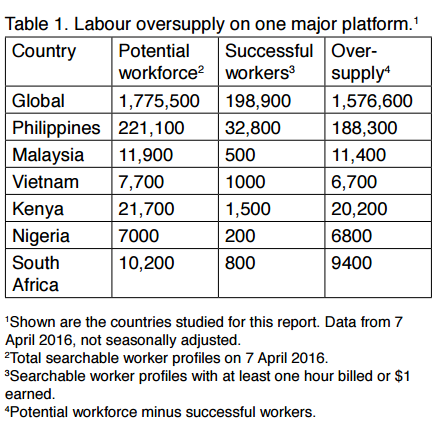

Unfortunately, the report doesn’t give any overall numbers for people working in this way, but one of the report’s authors, Mark Graham puts the figure at 48 million registered for work worldwide. However, the report’s access to one platform suggests that a lot of these are not actually finding much work – there is serious oversupply (see table) – more workers than jobs, which potentially spells bad news for wages and conditions. 94% of workers said they are not involved in any sort of labour union or worker association, and respondents frequently work over 70 or 80 hours a week for $3.50 per hour.

The gig economy was supposed to ‘disintermediate’ – putting northern clients directly in touch with southern online workers, but that didn’t last long. Because of the heavy role that reputational feedback scores play in online gig work platforms, work tends to flow to intermediaries/middlemen who already have a high score. These intermediaries then re-outsource that work, keeping a part of the client’s fee for themselves.

re-outsource that work, keeping a part of the client’s fee for themselves.

The report ends with some questions to those wishing to avoid this becoming a new form of cyber-slavery:

For Platforms

Is it necessary to list nationality on profile pages (which makes discrimination easier)?

Will online gig workers receive formal employment contracts in the future?

What formal channels could exist for workers to voice their issues?

For Policymakers

Where should governments regulate online gig work in the future (eg in country of origin of the clients, which tend to be better regulated)?

Will governments need to limit online gig work monopolies (‘positive network effects’ tend to lead to a few big players, rather than a competitive market)?

How will governments support alternative forms of platform organisation (e.g. online cooperatively-owned platforms)?

For Workers

What online forms of voice could emerge?

In what ways can existing groups (e.g. online networks, or freelancer unions) be used to promote solidarity?

To what extent will companies be held accountable for poor working conditions?

It ends by proposing a ‘Fairwork certification program’, which seems like a no brainer for a place to start.

All in all, a fascinating glimpse into a new, largely invisible and booming segment of the labour market – young, tech savvy people in developing countries tapping away on their laptops into the small hours for clients they never see.

April 23, 2017

How could a ‘life cycle analysis’ help aid organizations engage better with the public?

Following on the post (and great comments) about whether Oxfam should get serious on changing social norms, I’ve been thinking about a ‘life cycle  analysis’ approach to INGOs’ engagement with the public. The starting point is that at different ages, people have different assets and constraints (eg disposable time, cash, openness to new ideas). Obviously, one shouldn’t generalize – not all 20, 40 or 80 year olds are the same – but just for the sake of argument, let’s do so anyway. In the table below, I’ve allocated columns to Age, Assets, Constraints, Possible Aims for INGO engagement and entry points for that engagement. See what you think

analysis’ approach to INGOs’ engagement with the public. The starting point is that at different ages, people have different assets and constraints (eg disposable time, cash, openness to new ideas). Obviously, one shouldn’t generalize – not all 20, 40 or 80 year olds are the same – but just for the sake of argument, let’s do so anyway. In the table below, I’ve allocated columns to Age, Assets, Constraints, Possible Aims for INGO engagement and entry points for that engagement. See what you think

Age

Assets

Constraints

Possible INGO Aims

Points of Entry

0-5

Blank canvass, crucial age for shaping norms

No power, money

Building progressive social norms

Parents (esp mothers), faith organizations

6-18

Forming political opinions, lots of energy/idealism/time, can influence parents

Little money, power

More detailed shaping of values and opinions; broad campaigning; fundraising; badgering parents on eg advocacy or ethical consumerism

Schools, youth celebrities, faith orgs

18-24

Energy, time, idealism. Some future leaders/decision makers become easier to identify thanks to ‘sorting hat’ of university/discipline

Little experience, influence

Influencing future leaders eg via internships, volunteering, engagement with elite universities; long term recruitment

Elite universities/disciplines; Cultural ambassadors

25-45

Kids, growing influence in workplace (eg govt officials)

Kids (permanently knackered, broke)

Some advocacy with those in positions of influence, access to kids on norms; Long term retention

Progressive kids’ clubs (cf Woodcraft Folk); Light touch contact maintenance (email etc); Some sectoral advocacy engagement

46-65

More time (kids growing up, flying the nest), money, influence, experience

Still tied up in work/careers

FundraisingSome advocacy; Advisory roles

Advisory /mentoring roles to Oxfam teams and partners? Some specialist advocacy groups?

65-

Time, contacts, money

Energy levels and health declining over time

Grey Panther advocacy groups; Fundraising

Use supporter databases to identify clusters of people with similar experience/ interests; Identify ‘old men in a hurry’ to convene issue-specific advocacy groups (eg of ex bankers or accountants)

So who makes the best campaigner then?

When I did this exercise, what struck me was how little it resembles how Oxfam (and presumably other NGOs) currently engage with the public. We do next to nothing to shape norms during the early years of childhood, either directly or through parents and faith organizations. We see campaigns as primarily a role for youth, despite their lack of contacts, influence or staying power. Older people are too often treated as walking chequebooks rather than highly networked veterans with decades of experience we could draw upon.

Beyond just adapting engagement to the shifting sands of a person’s life cycle, we also need to move from ‘broadcast to conversation’ – a management slogan more often spoken than followed. That means acknowledging and responding to people’s varied and individual talents, experience, desires and agency, with ample space for feedback, suggestion and initiative as part of being an INGO supporter.

Exciting, and probably the way we have to go anyway, not least because people’s expectations are changing and they want more of this customized treatment and less of the ‘just trust us, we’ll make sure your money is well spent’ stuff. Customization could even extend to ‘disintermediation’ – finding a way to put people directly in contact, whether on donating (‘click here to send your cash straight to the SIM card of a person living in poverty’, a la GiveDirectly) or advocacy (‘sponsor a Women’s Rights Activist in a country of your choice’).

All good stuff, but it poses a huge challenge to business as usual, both in terms of the IT systems to allow all this to happen, but perhaps more fundamentally, to the culture and attitudes of traditional aid organizations.

Thoughts? (and thanks to Lizzie Williams and Foyez Syed for conversations on earlier drafts. Only fair to point out that Foyez was a bit scandalized by my blatant elitisim on universities and thought we should also be challenging the current system by promoting and developing leaders from different backgrounds. Fine, but we will never have the resources or scale to make much of a dent on that one, I fear.)

April 20, 2017

Improving collaboration between practitioners and academics: what to do? (with a little help from Einstein)

Previous posts in this 3 part series explored the obstacles to INGO-academic collaboration, and the lessons of systems thinking. This final post suggests some  ways forward (with some sarcastic asides from Einstein)

ways forward (with some sarcastic asides from Einstein)

Based on all of the above, a number of ideas emerge for consideration by academics, INGOs and funders of research.

Suggestions for academics

Comments on the blogposts that formed the basis for this article provided a wealth of practical advice to academics on how to work more productively with INGOs. These include the following:

Create research ideas and proposals collaboratively. This means talking to each other early on, rather than academics looking for NGOs to help their dissemination, or NGOs commissioning academics to undertake policy-based evidence making.

Don’t just criticise and point to gaps – understand the reasons for them (gaps in both NGO programmes and their research capacity) and propose solutions. Work to recognise practitioners’ strengths and knowledge.

Make research relevant to real people in communities. This means proper discussions and dialogue at design, research and analysis stages, disseminated drafts and discussing findings locally on publication.

Set up reflection spaces in universities where NGO practitioners can go to take time out for days, weeks or months, and can be supported to reflect on and write up their experiences, network with others and gain new insights on their work.

Catalyse more exchange of personnel in both directions. Universities could replicate the author’s ‘Professor in Practice’ position at the London School of Economics and Political Science, while INGOs could appoint honorary fellows, who could help guide their thinking in return for access to their work.

Suggestions for INGOs

In addition to collaborating in the ways discussed above, INGOs could encourage cooperation by:

Being open about their knowledge base, especially the large amount of data collected while monitoring and evaluating their projects. Oxfam now makes its impact evaluation survey data free to download.

Finding cost-effective ways of cooperating through long-term but loose networks maintained over time, which can be activated when necessary (e.g. in response to events or new priorities). This is less time intensive than establishing dense and time-consuming networks that often peter out for lack of resources.

Setting up arm’s length collaborative watchdogs on particular institutions or issues with a research function, that maintains a network of academics and activists, as well as maintaining institutional knowledge. Good examples are the Bretton Woods Projector Control Arms.

Building bridges at all levels of the knowledge ‘food chain’: INGOs need to go beyond the academic big names and conference attractions to build links with early career researchers. For example, Transparency International has set up a programme called Campus for Transparency that match-makes a Transparency International chapter or staff member who has a specific research need with a university MA programme or student who would then deliver this specific research product as part of their study requirement. PhD students can be involved along similar lines, provided the issues identified are sufficiently core to the INGOs’ work that they will not be made redundant by shifting priorities before the thesis is even written!

By insisting on evidence of impact, and supporting partnerships and consortia involving both researchers and practitioners, governments and aid donor funders already contribute significantly to bridging the academic–INGO divide. But they could do more, including the following:

Innovative financing – for example, offering 50/50 funding, half for programmes on the ground and half for research. At the moment donors seem to fund one or the other (research with a few links to practitioners, or programmes with a bit of money for monitoring, evaluation and learning), which misses a chance to foster deeper links.

They could also fund intermediary organisations with a mandate to build bridges between the two worlds. According to a recent Carnegie UK report:

Numerous studies reveal that people and small businesses outside universities find them impenetrable institutions. A member of the public or a community or voluntary organisation seeking a relevant point of contact in a university to discuss their research-related query often encounters a huge, incomprehensible organisation whose website is structured according to supply-side logic (faculties, departments, degree programmes) rather than according to demand considerations or user needs.

You can download the chapter in the IDS book on which these posts are based here.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers