Duncan Green's Blog, page 123

March 6, 2017

Links I Liked

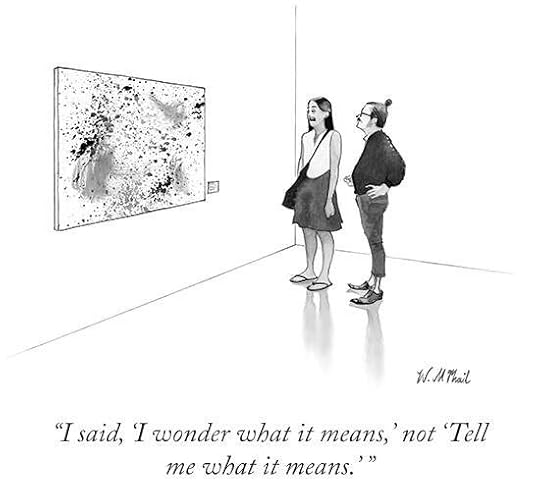

A little humour ahead of International Women’s Day. It’s the manbun that does it.

A lot of chat about the idea of a Universal Basic Income: the New York Times gave a glowing review of a UBI experiment in Kenya (h/t Josh Williams). Chris Blattman and Berk Ozler provided the bah humbug/’much more complicated than that’ response.

An initiative to fill the funding gap left by Pres Trump’s reintroduction of the global gag rule reached $190m. Kudos to the Dutch Government for convening and all the other donors (not including the UK, sadly) who chipped in.

An even-handed summary of what sounds like a really good (and heated) debate on private v public education in Africa

Chinese wages are now higher than in Mexico, Thailand, and Brazil,  according to this gated piece in the FT (h/t Max Roser)

according to this gated piece in the FT (h/t Max Roser)

Why economists love Machiavelli, and why he may be the best kind of leader the world can hope for, by Branko Milanovic

‘Hey guys, I’m just heading downstairs for my paleo pear and banana bread’…. Worst recruitment ad ever? Which PR muppet decided to force real life Aussie civil servants to take part in this squirm TV horror?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XvrcEjlSDvA

March 5, 2017

It’s not what you know but who: How social relationships shape research impact

James Georgalakis, Director of Communications and Impact at the Institute of Development Studies, introduces  a new collection of pieces on knowledge for development

a new collection of pieces on knowledge for development

If knowledge for development is a social process why do we continue to expect technical approaches alone, such as research methods, websites and policy briefs, to get evidence into action?

While it has been easy to share significant successes of getting research into action through impact awards and case studies, it has proved much harder to institutionalise any learning from these. Put simply, the development sector has continued to struggle to turn research into action. This challenge inspired my work with Ben Ramalingam (IDS), Nasreen Jessani (John Hopkins School of Public Health) and Rose Oronje (African Institute of Development for Development Policy) on a collection of peer reviewed articles about research impact which is published today. We wanted to address the gap between generic impact tool kits and conceptual frameworks and academic studies of research impact. So we commissioned evidenced case studies from those at the research-to-policy front line to provide practical learning for anyone seeking to make better use of evidence. What we learnt has implications for how you fund research, manage knowledge institutionally and promote its use in development policy.

A social process not a technical one

We spoke to NGOs seeking to inform programmes with learning, researchers attempting to influence policy with their studies and donors with requirements around assessing the impact of their grants. A common thread running through the resulting articles is the importance of social relationships in leveraging evidence into action. Put simply, our authors say that networks, individual relationships and cultural norms and politics hold the key to research impact. This is striking given that efforts to maximise research impact often focus on the process of evidence-informed policy as a largely technical and technocratic issue.

The barriers to the use of evidence in policy and practice are frequently described in terms of poor capability on key technical areas. For example, if researchers could just communicate more clearly – write policy briefs or take advantage of snazzy digital knowledge platforms everything would get better. On the demand side – if policy actors were more proficient in the assessment and use of evidence then research uptake would increase. These ideas have led to a sort of fetishisation of research communications products like the now ubiquitous policy brief. Get your research into the perfect brief (or press release or data visualisation) and in front of the right policy maker on the right day, or so the narrative goes, and impact will follow. Given my background is in policy communications you might think this is all music to my ears. A career beckons in teaching academics to write in plain English and how to use Twitter. Job done.

The barriers to the use of evidence in policy and practice are frequently described in terms of poor capability on key technical areas. For example, if researchers could just communicate more clearly – write policy briefs or take advantage of snazzy digital knowledge platforms everything would get better. On the demand side – if policy actors were more proficient in the assessment and use of evidence then research uptake would increase. These ideas have led to a sort of fetishisation of research communications products like the now ubiquitous policy brief. Get your research into the perfect brief (or press release or data visualisation) and in front of the right policy maker on the right day, or so the narrative goes, and impact will follow. Given my background is in policy communications you might think this is all music to my ears. A career beckons in teaching academics to write in plain English and how to use Twitter. Job done.

However, the use of research in the sphere of public policy is an extraordinarily complex phenomenon and is only one part of a complicated process that also uses experience, political insight, pressure, social technologies, and judgment. In international development, as with other spheres of public policy, decisions are likely to be pragmatic and shaped by their political and institutional circumstances rather than rational and determined exclusively by research. I admit there is nothing terribly original in pointing this out. The contextualisation of knowledge is well covered by a dizzying array of tool kits and impact guides for researchers. What is most striking about the treatment of this subject in our Collection is that in almost all of the case studies contextualising knowledge hinges on the navigation of power dynamics through personal contacts and informal networks.

It’s people not policy briefs that make the difference

In describing his project’s success in influencing national policy in Sierra Leone to support vulnerable children,

ESRC-DFID Joint Fund for Poverty Alleviation Research Programme grant-holder Mike Wessells argues that action research methodology would have been inadequate without the pivotal role played by UNICEF. What he describes is a process that incorporates both a networked approach to social relations and the very individualised dimension of a key personal relationship. It was the research team’s close working relationship with one particular UNICEF staff member that enabled them to navigate the tricky domestic political territory. This is contextualisation built on personal relationships and not on generic stakeholder mapping exercises conducted in workshops. Or as Mike puts it: “researchers who want to have a significant impact on policy should identify and cultivate a positive relationship with a well-positioned person who can serve as both a power broker and a trusted advisor.”

Meanwhile, MSF shared its challenges around bridging its medical research and academic work with local innovation. There was no obvious means of channelling or brokering new knowledge between these groups and vital new understandings, such as correct storage of insulin in the field, simply did not get translated into new practice on the ground. In the end brokerage was institutionalised through new ‘scientific days’ that brought researchers and innovators together in a safe social space for mutual learning. These are the organisational cultural contexts and social norms which shape knowledge systems.

If there is one key message that you take away from this collection I hope it will be that research to policy processes are largely social. Technical capacities matter of course (I do enjoy helping researchers with using social media and writing for policy audiences) but not nearly as much as the social factors. What we realised as we examined the case studies and think pieces we had commissioned is that there is a deeper set of layers to the social realities of knowledge for development. These social factors are: (i) The capacity of individuals and organisations in terms of knowledge and skills to engage in policy processes; (ii) Individual relationships that facilitate influence and knowledge brokerage; (iii) Networked relationships and group dynamics that connect up the supply of knowledge with the demand for it; (iv) and social and political context, culture and norms.

How can we create a more enabling environment for social and interactive knowledge exchange?

Despite this social reality we do not organise or fund our institutions, whether University faculties, NGOs or

But does he have any friends?

consultancies, to nurture this social use of science. Academics often move, on taking their contacts with them. INGOs flip and flop between policy and programme priorities and donors struggle to fund cross-sector collaborations. This is a huge contrast to the private sector: Lobbying firms send a junior staffer to every meeting with the key client to ensure continuity; the hedge fund invests heavily in developing key relationships; and the supermarket buyer carefully establishes close personal relationships with suppliers. These examples may sound incongruous with the development sector but in the health sector at least there are examples of strategies for utilising relationships to leverage evidence into policy.

An understanding of knowledge systems as fundamentally social has profound implications for the current predominance of technical approaches to evidence-informed development. Unless we can be more cognisant of these social realities when designing and implementing programmes we will never escape the general feeling of frustration shared by donors, researchers and practitioners that turning evidence into action is so hard.

These issues are the subject of a high level panel debate broadcast online today at 1600 GMT, co-hosted by IDS, ODI and IIED

The Social Realities of knowledge for Development, published by the ESRC DFID Impact Initiative for International Development Research, can be downloaded for free

March 2, 2017

The Economist profiles Gender Budgeting ahead of International Women’s Day

There appears to be some kind of feminist cell operating at the Economist. Without ever mentioning International  Women’s Day (next Wednesday), they slipped in a wonderful tribute to Diana Elson and her work on gender budgeting, with the header ‘TAX is a feminist issue’. Here it is, (I’ve added a few links). Hope I haven’t blown their cover.

Women’s Day (next Wednesday), they slipped in a wonderful tribute to Diana Elson and her work on gender budgeting, with the header ‘TAX is a feminist issue’. Here it is, (I’ve added a few links). Hope I haven’t blown their cover.

Why national budgets need to take gender into account

Designing fiscal policies to support gender equality is good for growth

Like many rich-country governments, Britain’s prides itself on pursuing policies that promote sexual equality. However, it fails to live up to its word, argues the Women’s Budget Group, a feminist think-tank that has been scrutinising Britain’s economic policy since 1989. A report in 2016 from the House of Commons Library, an impartial research service, suggests that in 2010-15 women bore the cost of 85% of savings to the Treasury worth £23bn ($29bn) from austerity measures, specifically cuts in welfare benefits and in direct taxes. Because women earn less, rely more on benefits, and are much more likely than men to be single parents, the cuts affected them disproportionately.

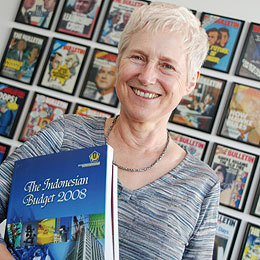

The government does not set out to discriminate, says Diane Elson, the budget group’s former chair. Rather, it overlooks its own bias because it does not take the trouble to assess how policies affect women. Government budgets are supposed to be “gender-neutral”; in fact they are gender-ignorant. Ms Elson is one of the originators of a technique called “gender budgeting”—in which governments analyse fiscal policy in terms of its differing effects on

Diane Elson. With budget.

men and women. Gender budgeting identifies policies that are unequal as well as opportunities to spend money on helping women and which have a high return. Britain has declined to adopt the technique, but countries from Sweden to South Korea have taken it up.

Ms Elson and her colleagues argue that, once you break down public spending, the opportunities stand out. For instance, if the British government diverted investment worth 2% of GDP from construction to the care sector, it could create 1.5m jobs instead of 750,000. Many governments treat spending on physical infrastructure as an investment, but spending on social infrastructure, such as child care, as a cost. Yet such spending also increases productivity and growth—partly by increasing the number of women in the workforce.

In poorer countries, the bias can be more explicit. When Uganda first looked at its budget through a gender lens, it discovered that little of the spending on agriculture was going to support women farmers, though they did most of the work.

What may sound simply like feminism infiltrating fiscal policy is thus also about efficiency. Gender budgeting is good budgeting, argues Janet Stotsky, who led an IMF survey of such efforts around the world. You don’t have to be a feminist to accept that investing in girls’ education or in women’s labour-force participation will generate a high return on investment.

Such a utilitarian approach appeals to finance ministries in a way that pious talk of “women’s empowerment” may not. Ministries can fail to grasp how their budgets affect women and girls. In developing countries, for instance, investment in clean water and electricity eases housework, freeing time for mothers to earn money and for girls to go to school. Cutting funding may save money in the short term, but when women spend their days fetching water, growth suffers.

There are plenty of examples of the idea in action. In Rwanda spending aimed at keeping girls in school—such as

providing basic sanitation—has led to higher enrolment. In India the use of gender budgeting in a state is a better indicator of girls’ school attendance than higher incomes. In South Korea a lack of child care has forced women to choose between work and family. Both female labour-force participation and fertility rates are low—a poor formula for growth in an ageing country. Gender budgeting helped the government design programmes to reduce the burden of care on women. Around the world, safer transport systems can ease the vast, often unseen, burden of violence against women and girls—in medical costs, and lost productivity and labour, as they are prevented from working or learning.

Gender budgeting has won the backing of international financial institutions. Ms Elson once took the IMF and the World Bank to task for their bias, arguing that austerity forced on countries seeking funds in the 1980s imposed heavy burdens on women. Now the World Bank backs gender budgeting. The IMF used not to see promoting sexual equality as its job, but Christine Lagarde, its managing director, now wants gender-budgeting to play a role in the advice it gives to member countries.

Not everything has gone well for gender budgeting, however. Some initiatives have proved half-hearted, short-lived or prey to party politics. Egypt introduced the concept in 2009, encouraged by international donors; when the donors left, it petered out. Australia was the first country to have gender budgeting. But today’s conservative government saw it as left-leaning and anti-austerity and dropped it in 2014, the year after it took office.

Other countries have issued sexual-equality statements and begun tracking data, but have not changed budget allocations. Much of their reluctance can be put down to bureaucratic inertia—and the sheer difficulty of the process of tracking who gets what. Fiscal policy is based on the market economy, which generates cash, and ignores women’s unpaid labour, and the extent to which it limits their work in the market economy. Rather than rethink the system, governments rely on equal-opportunity laws to cut inequality—though the evidence is that they do not.

Professing loyalty to an idea is easier than acting on its implications. “Everyone is keen to take on gender equality if it only means marginal changes,” says Ms Elson. “Root-and-branch changes to thinking about how the fiscal system supports gender equality are much more difficult.”

March 1, 2017

WDR 2017 on Governance and Law: great content, terrible comms, and a big moral dilemma on rights and democracy

Spoke yesterday at the London launch of the 2017 World Development Report on Governance and The Law.  Although Stefan Kossoff did a great job in summarizing the report on this blog a few weeks ago, I thought I’d add a few thoughts from the discussion.

Although Stefan Kossoff did a great job in summarizing the report on this blog a few weeks ago, I thought I’d add a few thoughts from the discussion.

The current debates on governance, of which the WDR is part, bear some of the hallmarks of a paradigm shift: widespread dissatisfaction with the existing approach (engineering institutional reforms in accordance with some notion of ‘best practice’, which hardly ever works); a growing body of evidence that another approach (broadly, that set out in the WDR) corresponds better to reality. The contribution of the WDR is in systematizing what we know so far, legitimizing the views of people who until a few years ago were seen as heretics, and providing the endorsement of a big and prestigious institution (the World Bank). That all feels like a significant moment.

But there are a couple of big challenges:

How do advocates of this way of ‘Doing Development Differently’ deal with the ‘well, duh’ factor? If you go up to a policy wonk, a decision maker, or an aid worker and say ‘hey, it’s all about politics and power’, they are likely to look at you with contempt and say, ‘well, duh. Tell me something I don’t know’. Unless you have a very specific comeback that shows them what they need to do differently because of that observation, they will stop reading/listening. The WDR only gets part way there.

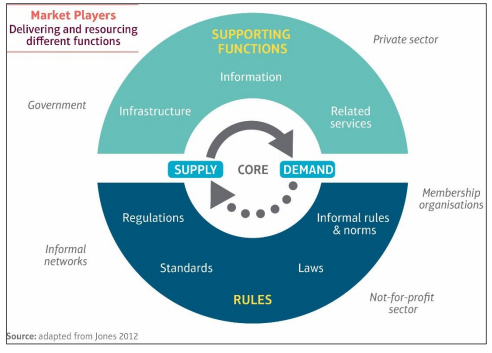

Comms: the report is full of brilliant content, but there is no denying it is a tough read. If you ask a bunch of economists and political scientists to collaborate, don’t expect a page turner. There is no memorable meme or diagram (this is the best there is), just lots of lists of three things, which I can’t for the life of me remember. I think the best thing that the Bank could now do is hand over the report to some comms people who take it away and turn it into something more accessible.

Comms: the report is full of brilliant content, but there is no denying it is a tough read. If you ask a bunch of economists and political scientists to collaborate, don’t expect a page turner. There is no memorable meme or diagram (this is the best there is), just lots of lists of three things, which I can’t for the life of me remember. I think the best thing that the Bank could now do is hand over the report to some comms people who take it away and turn it into something more accessible.

What’s the Theory of Change? More generally, applying the WDR’s own thinking to influencing decision makers, its supporters need to think through their theory of change. A few thoughts:

Getting this discussion out of the ghetto of governance and aid needs new stories and new champions. Maybe try and persuade a couple of governments to be ‘labs’ for the WDR approach, finding champions in other sectors (health, education, infrastructure, economy) and recruiting diplomats (who get this) as well as technocrats (who often don’t)?

Critical Junctures: what are the windows of opportunity provided by shocks and crises? In normal times, it’s probably unwise to tell politicians that this is a way of achieving more impact with less money, because the likely response is ‘great, here’s less money then’. But if they have already made that decision, eg possibly in the case of the US aid programme right now, maybe this is the moment to sell the ideas in the WDR to decision makers faced with a ‘burning platform’?

And one real dilemma. British aid minister Rory Stewart (who definitely gets this stuff – he spoke without notes, listened intently to the presentations, stayed for the whole meeting. V impressive) opened the meeting by asking whether the report should have talked more about human rights and democracy – depending on who you believe, these kind of ‘inclusive institutions’ are either instrumental in achieving other benefits like stability and growth, or an intrinsic aspect of development, or both.

Great question. The WDR argues that people interested in governance and public policy should stop fixating on  ‘form’ and think about function. As Deng Xiao Ping put it – it doesn’t matter if the cat is black or white as long as it catches mice. In some ways this is liberating – it means that rather than assuming that development means everywhere ‘looking like us’, or at least like our idealized version of ‘us’, we should try harder to understand the huge variety of institutions and how they can deliver (or not) stability, justice, services. That sounds right – more attuned to complexity, less imperialist and arrogant.

‘form’ and think about function. As Deng Xiao Ping put it – it doesn’t matter if the cat is black or white as long as it catches mice. In some ways this is liberating – it means that rather than assuming that development means everywhere ‘looking like us’, or at least like our idealized version of ‘us’, we should try harder to understand the huge variety of institutions and how they can deliver (or not) stability, justice, services. That sounds right – more attuned to complexity, less imperialist and arrogant.

But what if the ‘form’ we are abandoning in search of function is democracy or human rights? Some people in the governance debate seem positively gleeful about jettisoning these and focussing instead on what institutions produce stability, growth etc etc. They often get quite dewy eyed about autocracy in countries like Rwanda, Ethiopia or China.

I disagree with that, not least because I buy into Amartya Sen’s timeless definition of development as the progressive expansion of the freedoms to be and to do, so what is happening in those countries is clearly not development in its fullest sense, even if economies are growing and people are eating and living longer.

But the human rights and democracy crowd are equally unconvincing when they try and argue that good governance, rights, inclusive institutions etc are essential to development. They come up against the China Question – if that’s true, what about China? At worst, authors like Acemoglu and Robinson in Why Nations Fail make themselves look a bit ridiculous by arguing that China is a blip, destined to collapse because it doesn’t have inclusive institutions. It’s not China that looks like collapsing right now….

So after publicly agonising in the meeting, I ended up replying to the Minister that this was indeed a dilemma, since most of the writing about governance errs towards the latter position, I welcomed the WDR rebalancing the debate a bit (and its sections on China are some of its best). Not really adequate, I know.

Overall, I think it will take months (if not years) for people to digest this report, and for its impact to become clear, but I would urge everyone to get started right away.

Here’s the video of the event, in case you missed it. I start ranting at minute 40.

February 28, 2017

How can media inspire accountability and political participation? Findings from massive BBC programme.

A recurring pattern: I get invited to join a conversation with a bunch of specialists on a particular issue (eg market  systems). Cue panic and some quick skim-reading of background papers, driven by the familiar fear of finally being exposed as a total fraud (some of us spend all our lives waiting for the tap on the shoulder). Then a really interesting conversation. Relief!

systems). Cue panic and some quick skim-reading of background papers, driven by the familiar fear of finally being exposed as a total fraud (some of us spend all our lives waiting for the tap on the shoulder). Then a really interesting conversation. Relief!

Last week it was the role of the media in governance, a conversation at the Ministry of Truth BBC, organized by the excellent BBC Media Action, the BBC’s international development charity. Recording here.

What emerged was a picture of increasing churn and fragmentation – a media and information ecosystem that is casting off vestiges of linearity (a few big newspapers and one or two big TV and radio stations) and becoming far more complex (social media, online, local radio, ever more channels of everything).

In response, just as with governance and markets, those trying to promote change and development are starting to think in terms of systems rather than linear theories of change. It’s no longer good enough (if it ever was) to look for the lever to pull to trigger change (a new law, an article in the FT). Instead, just as with governance, there is a twin track emerging:

Enabling environment: Broad brush support through legislation (right to information, media independence, protecting sources), access (spread of 4G, literacy) is a role for outsiders that doesn’t require them to fathom the complexity of local media systems.

Enabling environment: Broad brush support through legislation (right to information, media independence, protecting sources), access (spread of 4G, literacy) is a role for outsiders that doesn’t require them to fathom the complexity of local media systems.

However, the consensus in the room was that this is not enough – echoes of the Twaweza debate a few years back, where they found that the theory of change ‘giving people access to information → social and political action’ failed because they hadn’t thought about the assumptions behind the arrow.

So what else is needed? An excellent summary of the evaluation by BBC Media Action of a massive 6 year, DFID-funded project on using media to increase accountability by inspiring political participation (it reached >190m people in 12 countries) provided some interesting clues (full evaluation here):

Enabling discussions and brokering relationships, not just providing information (seems like we’re learning from the experiences of Twaweza)

The centrality of local context – eg some societies and cultures (and political systems) like confrontational media formats, while others prefer collaboration. The implication for funders is the importance of local staff and local partnerships – outsiders are never going to understand the system

Critical Junctures (eg elections, natural disasters or protest movements) provide the natural rhythm for engaging both with media and politics

An associated research report claims ‘audiences participate more in politics than people who do not listen to and/or

watch its programmes, even when taking other influencing factors – such as age, income and interest in politics – into account’. Not sure whether that is attribution or association (eg what if a third factor, like church or other organizational membership or family background, leads people both to watch socially aware programmes and take part in political action?) but will leave that to the evaluation geeks.

Digging into the numbers a bit further, the evaluation also found a mixed picture on the equity impact of its media  work: larger increases in participation were seen in groups that traditionally participate less, but on the other hand, the increase in participation was greater among men than among women (presumably because of other constraints on mobility, time etc).

work: larger increases in participation were seen in groups that traditionally participate less, but on the other hand, the increase in participation was greater among men than among women (presumably because of other constraints on mobility, time etc).

Other points that came up in the BBC panel:

Commercial sustainability is crucial. No point an aid organization going in and funding lots of good stuff if it either collapses or is coopted by some oligarch when the project comes to an end.

The debate was conducted as if there are facts (that can be established with absolute certainty) and lies (ditto), but in practice there are substantial grey areas in between. For example any prediction about the future (Brexit will do X to trade, GDP, immigration etc) falls well short of hard fact, in my book. Most public opinion polling probably does too. Without going all post-modern about it, we need to acknowledge that a lot of public debate takes place in the grey area, which for me merely underlines the fact that narratives matter as much/more than numbers.

Final thought: the dance felt familiar, even if the dancers were different. This same shift in thinking, from linear to systems, has been going on among different disciplinary groups working on governance and institutions, markets, gender etc etc. I fear that they are each separately learning the same lessons the hard way. What would happen if we got them all into a room? Probably one of two options – the bad one would be if they each started vigorously lobbying each other – ‘you need to do more on our issue, can’t you see how important it is?’ So how could you design the conversation so that they stand back and learn from each other and maybe save some time and effort?

For starters, you would need the right convenor – an institution or individual perceived as impartial and credible, who brings everyone together to take stock on and compare the parallel linear→system transitions currently under way. Has anyone already done this?

February 27, 2017

What does the rise of Digital Development mean for NGOs?

Matt Haikin

, an ICT for Development (ICT4D) practitioner, summarizes a

new paper

on digital development in

Matt Haikin

, an ICT for Development (ICT4D) practitioner, summarizes a

new paper

on digital development in  East Africa reports, and the challenges for Oxfam and other international NGOs

East Africa reports, and the challenges for Oxfam and other international NGOs

I’d been living in Nairobi for a couple of months, meeting all the interesting ‘tech for good’ types I could find (and there are a LOT for one city!), when an opportunity came up to conduct some research for Oxfam into… tech for good activity and opportunities in HECA (Horn, East and Central Africa), along with my colleague George Flatters). Result.

For the next few months we met, interviewed and held workshops with 50+ experts from NGOs, tech start-ups, government and civil society as well as donors and academics from across the region, and reached almost 300 more people with an online survey.

The research report and discussion paper was published last week. We think the findings are relevant for other organisations trying to improve their use of ICT or put the Digital Principles into practice and a few of these findings are highlighted below:

Build on what works: When it comes to ICT4D, we usually know what works and it rarely involves the newest technology. Mostly the tools already exist or, where they don’t, an approach can be adapted from something that  does. We recommend collaboration with other organisations, such as local technology partners, which will develop the capacity of the entire sector at the same time.

does. We recommend collaboration with other organisations, such as local technology partners, which will develop the capacity of the entire sector at the same time.

Why are we still bad at being adaptable and co-designing with users? In our survey, iterative and user-centred approaches to technology for development were nearly universally acknowledged as a good thing, no big surprise there. However many reflected on the structural factors that seem to be preventing their more widespread adoption – skills gaps, incompatible funding models and the absence of nurturing ecosystems.

Avoiding survey fatigue as mobile technology proliferates. The combination of an increasing focus on M&E, with low costs of online / mobile surveys, risks over-exposing communities to questionnaire after questionnaire from multiple agencies. There is an appetite to collaborate more, across projects and across organisational boundaries, but it all depends on being able to change long-standing cultures to encourage organisations to share and open up much more data (while retaining a respect for privacy and sensitive information of course).

Don’t forget about connectivity: According to the 2016 World Development Report, ‘nearly 60% of the world’s people are still offline… only 31% of the population in developing countries had [internet] access in 2014 and women are less likely than men to use or own digital technologies.’ A lot of the discussion in the ICT4D space has moved beyond issues of connectivity, when in fact a lack of connectivity remains the biggest technology challenge for much of the world. In the rush to embrace new technologies, smartphone apps, mobile surveys, the Internet of Things etc., we must ensure we design for the significant numbers of the people who are not connected, and lobby to get them connected.

We found that the tech community across Africa would be widely supportive of a move to NGOs to focus more on convening, collaborating and advocating, and away from direct delivery. All of these roles seemed to cut through the normal mixed-opinions about NGOs and the aid sector, all had 80/90% agreement amongst those surveyed, and all seem like a natural progression that aligns with the direction of travel already under way in Oxfam and many other international NGOs:

NGOs as ICT4D convenors: International NGOs can play a valuable role in convening partners from different sectors and helping develop the capacity of local actors – co-creating shared best practice guidance for technology development and product selection, supporting upskilling of local people and partners and, ultimately, facilitating the emergence of a bottom-up ICT4D agenda owned and led by African partners.

NGOs as ICT4D collaborators: NGOs could do more to work with each other to develop shared product requirements and reduce the waste and overlap in producing overly similar tools; and more importantly could do more to collaboratively with local partners (as equals not just as service providers) – helping develop their capacity, and enabling them to take the lead.

NGOs as advocates for ICT4D: NGOs are uniquely placed to exert pressure on donors, multi-lateral institutions and governments. If they can adapt to become more collaborative and become a voice genuinely representative of their local partners – they could be a powerful voice in changing the way these bigger players work – to be more flexible, less top-down, more supportive of developing local capacity, more driven by those actually working with tech in development than those working in policy in London, DC, Brussels etc.

And just to recap, why is digital an opportunity NGOs should seize?

And just to recap, why is digital an opportunity NGOs should seize?

Right now, digital technology is the darling of the private and public sectors, this gives it (rightly or wrongly) a certain level of influence which more bottom-up, analogue demands for change struggle to create.

Digital technology is disruptive; it creates major change whether we like it or not –we can try to ignore it or we can use it as an opportunity to take drive significant and powerful changes that would be difficult at other, less turbulent times.

Digital technology is here to stay, NGOs need to adapt to it, it’s not going away. For now it is still bedding down as a system, which means it is malleable. Once it becomes fixed, the window of opportunity to influence it and use the disruption it causes to make change for the better will vanish.

Matt Haikin is an ICT4D practitioner, researcher and evaluator who has undertaken development/research work for DFID, the World Bank and the government of Nigeria. He blogs intermittently and can be contacted via www.matthaikin.com

February 26, 2017

Links I Liked

A long Links I Liked this week – reading at the top, videos at the bottom

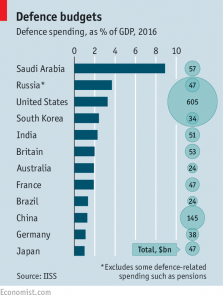

War Defence budgets. 2016 update from the International Institute of Strategic Studies. The top 10 now spend a total

of $1.1trn (8 times the global aid budget). The US is still top but the balance of spending is moving to Asia.

DFID & the EU are going large on cash transfers to refugees in Lebanon and shaking up humanitarian system in the process.

Satellites are getting better at measuring poverty. New research from Aid Data and Stanford University. Suitably nerdy video summary here.

According to Bill Gates, robots should pay income tax, the same as humans, in order not to have unfair advantage. Interesting, like a Tobin Tax on automation, but how on earth would this work? eg where’s the boundary – will they tax my laptop? And will robots get to vote in return (no taxation without representation and all that)?

How long before microfinance programs and vocational training are imposed by the cops? Chris Blattman has a dystopian moment.

Lots of video/film related links on muslim women this week

The Indian censor bans Oxfam award-winner ‘Lipstick Under my Burkha’ as too ‘lady orientated’. Is that even a thing? The trailer suggests it is quite raunchy for my tender sensibilities, but hardly pornographic.

Nike gets in on the act with a commercial celebrating Arab women athletes who dream big and compete in the sports they love. Good discussion by Nida Ahmad here

Meanwhile, back in real life, women liberated from ISIS controlled areas in Iraq remove their veils and try to burn them (they don’t seem very flammable, unfortunately)

Film for Development. Fantastic trailers for films used to promote development (rather than raise money). From refugees in a Kenyan camp watching Team Refugees compete in the Rio Olympics to MTV Shuga’s excruciatingly awkward visit by two young women to a family planning clinic – not sure it’s going to encourage many other teenagers to follow suit.

February 23, 2017

How introducing electronic votes in Brazil saved lives and increased health spending by a third

Just came across a paper which overcame even my scepticism about what often seems excessive hype around  technology’s impact on poverty and human rights. Check out ‘Voting Technology, Political Responsiveness and Infant Health: Evidence from Brazil’ by Princeton’s Thomas Fujiwara. He has stumbled across one of those wonderful natural experiments that allow you to try and pin down the causal impact of a particular change.

technology’s impact on poverty and human rights. Check out ‘Voting Technology, Political Responsiveness and Infant Health: Evidence from Brazil’ by Princeton’s Thomas Fujiwara. He has stumbled across one of those wonderful natural experiments that allow you to try and pin down the causal impact of a particular change.

In this case it was the gradual introduction of electronic voting (EV) systems to replace hyper-complicated forms that meant that large numbers of Brazilians, in particular those who were poor and/or illiterate, messed up their voting forms and were effectively disenfranchised. EV makes it much easier to get it right (it reduced spoiled ballots by about 10% of total voter turnout). The experimental bit lies in the gradual introduction of EV, which allowed Fujiwara to use a regression continuity design (me neither) to isolate what happened where EV was and wasn’t present. Its introduction was thus effectively a demonstration of what happens when poor people get to vote. Neat, eh? Here’s the findings:

‘EV caused a large de facto enfranchisement of less educated voters, which led to the election of more left-wing state legislators, increased public health care spending, utilization (prenatal visits), and infant health (birthweight)…… The estimates indicate that the de facto enfranchisement of approximately a tenth of Brazilian voters increased the share of states’ budgets spent on health care by 3.4 percentage points, raising expenditure by 34% in an eight year period. It also boosted the proportion of uneducated mothers with more than seven prenatal visits by 7 percentage points and lowered the prevalence of low-weight births by 0.5 percentage points (respectively, a 19% and −68% change over sample averages).’

‘EV caused a large de facto enfranchisement of less educated voters, which led to the election of more left-wing state legislators, increased public health care spending, utilization (prenatal visits), and infant health (birthweight)…… The estimates indicate that the de facto enfranchisement of approximately a tenth of Brazilian voters increased the share of states’ budgets spent on health care by 3.4 percentage points, raising expenditure by 34% in an eight year period. It also boosted the proportion of uneducated mothers with more than seven prenatal visits by 7 percentage points and lowered the prevalence of low-weight births by 0.5 percentage points (respectively, a 19% and −68% change over sample averages).’

Wow. Electronic voting enfranchises 10% of the population, a previously excluded group that then elects authorities that increase health spending by a third over 8 years. And for someone like me who focuses on poverty and power, rather than technical fixes, the nice part is that in this case technology is improving the working of politics, not bypassing it.

February 22, 2017

How are different governments performing as global citizens? Time for a new index!

Apologies. I get given stuff at meetings, it goes into the reading pile, and often takes months to resurface. So I have  just read (and liked) a Country Global Citizenship Report Card handed to me in New York in December. It’s put together by the Global Citizens Initiative, run by Ron Israel.

just read (and liked) a Country Global Citizenship Report Card handed to me in New York in December. It’s put together by the Global Citizens Initiative, run by Ron Israel.

Time to assuage my guilt.

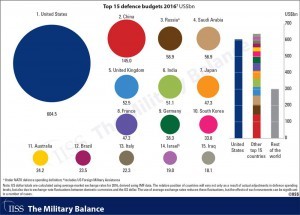

The ‘citizens’ in question are actually 53 governments, and the report assesses them against their signature, ratification and particularly implementation of 35 international agreements, conventions and treaties. These fall into 6 domains: human rights, gender equity, environment, poverty reduction, governance and global peace and justice. The implementation part is the trickiest, and the initiative seems to pull together a range of multilateral and academic scorecards for the various issues, eg environmental stewardship includes:

‘Reduce Pressure on Earth’s Resources

‘Reduce Pressure on Earth’s Resources

Ecological Footprint – Global Footprint Network

Ecological Reserve/Deficit – Global Footprint Network

Energy Use per $1,000 GDP – World Bank

Forests score – Yale University’s 2014 Environmental Performance Index

Reduce Air Pollution

Ambient (Outdoor) Air Pollution (PM2.5 ug/m3) – World Health Organization

Air Quality score – Yale University’s 2014 Environmental Performance Index

CO2 Emissions (metric tons per capita) – World Bank’

And so on – 116 indicators in all. Here’s the overall country ranking – not many surprises, with the Scandinavians top of the heap, as usual, and Iran, Saudi Arabia and Afghanistan at the bottom.

Some other findings jumped out:

The highest scoring domain by far is Gender Equity, with 26 countries signing all six selected international commitments, although implementation is much more patchy

‘Ratifying international treaties and conventions does not necessarily lead to measurable progress in those particular areas’. Argentina was the only country to ratify all 35 international commitments, yet came in 19th on implementation.

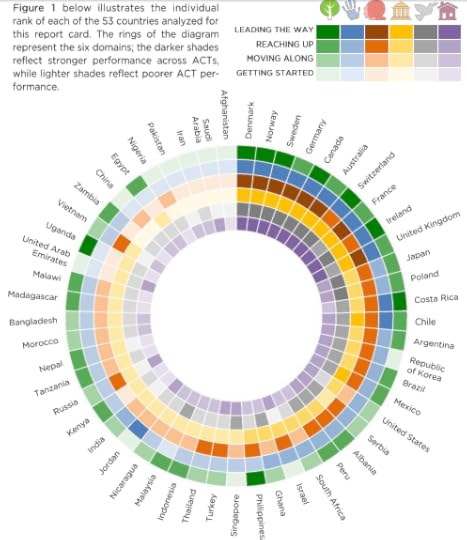

The report rather bravely sets out its theory of change (see diagram below) which begs a lot of questions – what assumptions lie behind the arrows? What else is required for publishing the card to galvanize all this advocacy? E.g. buy-in from powerful players, crises and scandals which open up decision makers to new ideas, grassroots movements to push for the same issues (see Htun and Weldon on violence against women)?

Which took me back to the Sustainable Development Goals. What is the SDGs’ theory of change? Is it any more sophisticated than this? I suspect not. In fact, it may not even be as good – for example merely assuming that government commitments + measurement will trigger some kind of change. So are we going to see a comparable SDG scorecard that ranks countries, shames foot-draggers and gives civil society something to shout about? Can we build on some of the interesting research out there about which international instruments get traction on national governments and why?

Which took me back to the Sustainable Development Goals. What is the SDGs’ theory of change? Is it any more sophisticated than this? I suspect not. In fact, it may not even be as good – for example merely assuming that government commitments + measurement will trigger some kind of change. So are we going to see a comparable SDG scorecard that ranks countries, shames foot-draggers and gives civil society something to shout about? Can we build on some of the interesting research out there about which international instruments get traction on national governments and why?

Because of its apparent lack of a coherent theory of change, I more or less gave up on the SDGs long ago, but would be happy to be proved wrong – what do the SDG watchers among you think? Are they generating traction on national decisions and if so, how and where? Is there a brilliant SDG theory of change that I am just not aware of?

Anyone know of other global scorecards on rights commitments and implementation?

February 21, 2017

How do we encourage innovation in markets? What can systems thinking add?

Earlier this month I spent a fun 3 days at a seminar discussing Market Systems Innovation. No really. I discovered a  community of very smart people working on markets, who seem to be on a similar journey to the people working on governance and institutions, who I have spent most of my time with in recent years. Chatham House Rule, so the speakers must remain shrouded in mystery, but I will say it was at the Rockefeller Foundation’s Bellagio Centre, just to make you jealous. FSG convened the event (I nicked their slides on the India dairy story),

community of very smart people working on markets, who seem to be on a similar journey to the people working on governance and institutions, who I have spent most of my time with in recent years. Chatham House Rule, so the speakers must remain shrouded in mystery, but I will say it was at the Rockefeller Foundation’s Bellagio Centre, just to make you jealous. FSG convened the event (I nicked their slides on the India dairy story),

The market systems crowd have been on a familiar journey: they started with a focus on individual entrepreneurs and firms – how to encourage them to innovate, grow etc? Then they became aware of the surrounding economic systems as barriers – what if you can’t get your products to market, or the banks won’t lend to you? So they learned to identify bottlenecks and obstacles and try to overcome them. But that is a static picture of the system – a series of snapshots. It misses the pockets of momentum, how the system is constantly changing, throwing up potential opportunities. Now the MSI folk are ready to ‘dance with the system’. That means thinking more about how to boost the system as an ‘enabling environment’ rather than just see it as a series of problems that need fixing. It also means studying the history of any given market system – essential to dig into the path that has brought it to its current state, and the influence that is likely to have on any attempt to change it. There

was some really impressive use of timelines to delve into the history of particular markets like India’s iconic Amul dairy project (see slides).

was some really impressive use of timelines to delve into the history of particular markets like India’s iconic Amul dairy project (see slides).

I realize that probably sounds like a load of meaningless management babble, but I think there is some substance here. Bear with me.

The bit I got excited about (and pushed remorselessly) was the importance of social/gender norms that block off/open up areas of market activity without firms even realizing. There’s a great example from Bangladesh in one of the background papers for the conference:

‘Katalyst (a market development project) supported large private seed companies to expand their input distribution channels in the northern remote areas of Bangladesh to become more gender inclusive. Katalyst assisted with market research, developing a business model, and showing that women took leading roles in vegetable production and were an important clientele. Ultimately, the input companies were able to design and sell, via female door-to-door sales agents, small affordable packages of quality seeds to customers, 90 percent of whom were women. One leading company, Lalteer seeds, experienced a 50 percent hike in sales of mini-packet seeds to homestead producers in the chars. As a result women are growing more vegetables more efficiently, with positive implications on the household consumption of vegetables as well as increased disposable income for women from selling excess vegetables. Katalyst will build on this success by designing interventions to attract buyers to purchase from the farm gate so that women have access to output markets, without compromising their mobility. Such activities ensure that women are able to access markets without compromising their ability to meet household responsibilities or challenge norms around mobility.’

I was in a small group that was tasked with coming up with some guidance for market systems people on how to work with/on social norms. We identified 3 areas: diagnosis, working within constraints (like the Bangladesh example of finding markets solutions compatible with restrictions on women’s mobility) and deliberately trying to tackle norms head on. Few market systems organizations are going to go all the way to start campaigning for norm change (e.g. funding feminist activism), but all are capable of doing better on the first two categories– making norms visible (for example using a gendered market analysis), and finding work-arounds when norms are excluding people from markets. Another background paper looked at the care economy – v useful.

Finally, as with the governance debate, talk of systems thinking seems to generate two contradictory responses in  people. One lot cry ‘whoopee, we need some new, and preferably really complicated, toolkits’, and start messing around with Social Network Analysis and the like. The others say ‘let’s embrace ambiguity and doubt. Forget data, it all comes down to judgement.’ They cite investors looking for promising companies, who often say they ignore the business models and project proposals, which they assume will change massively during the course of a project. What they are interested in is the quality of the management team and its ability to sense and respond to change and new information. The second camp also loves broad enabling environment issues like transparency and access to information.

people. One lot cry ‘whoopee, we need some new, and preferably really complicated, toolkits’, and start messing around with Social Network Analysis and the like. The others say ‘let’s embrace ambiguity and doubt. Forget data, it all comes down to judgement.’ They cite investors looking for promising companies, who often say they ignore the business models and project proposals, which they assume will change massively during the course of a project. What they are interested in is the quality of the management team and its ability to sense and respond to change and new information. The second camp also loves broad enabling environment issues like transparency and access to information.

I fall somewhere between the two camps – we need some general tools (eg power analysis, systems mapping), but keep it simple – not some big new machine. But then it’s time to go and find the firms and individuals who are doing interesting things and see what you can learn (positive deviance). And add to that lots of advocacy on everything from access to finance to women’s rights.

Views?

Final plug. Oxfam has a rather good and non-geeky intro to market systems and an accompanying 5m video

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers