Duncan Green's Blog, page 126

January 24, 2017

Local governance and resilience – what lasts after the project ends?

Jane Lonsdale

reflects on the lessons from an ‘effectiveness review’ of a Myanmar project 18

months after it ended. For the nerds among you, an accompanying post on the nuts and bolts of the effectiveness review has just gone up on the ‘real geek’ blog

We have just finished a review of Oxfam’s work in Myanmar’s central Dry Zone. This was designed some 6 years ago – a lifetime in Myanmar, back when the country was far more closed, and we were trying to disguise governance work as a resilient livelihoods project. Our intentions were to help communities prepare to face future potential upheaval, including:

Political –it was very uncertain what direction Myanmar would take back in 2010,

Economic – such as sharp increases in agriculture inputs or falls in agricultural prices, or

Climatic- droughts or floods in the case of the Dry Zone – which the area is annually at risk of.

To do this we focused on building durable community structures, knowledge, and jointly exploring existing and new ways to cope with potential uncertainty. The activities included community development, Participatory Community Vulnerability Assessments and planning, a revolving fund as a way to support the most vulnerable in the community to handle the hungry season, and support on domestic and agricultural water, collective buying and selling, and cotton and beans growth and trade as the two value chains that could work best for women.

This was our working definition of resilience, and what we thought it would take to increase it in this context.

The study looks at how many of the Member Organisations (a version of Community Based Organisations) that we helped to establish were still operating, to what degree, and what made them continue. We were working in areas where no structured community organizations had previously existed, with little NGO presence at the time, so Oxfam had to use a mix of direct implementation and working with NGO partners, where they existed.

What did the review find? Some success, some failure, and a lot of interesting lessons. Of the MOs

researched, 18 months on 62% were ‘hopeful or maturing’, and 38% ‘struggling’; none were completely dysfunctional or 100% effective. What I found most interesting was the strong correlation between good MO performance, and strong livelihood and resilience improvements (and vice versa – weak MOs correlated with weak improvements), supporting our hypothesis that

The inevitable theory of change diagram

capable and well functioning MOs can make a difference in current and future livelihood conditions. That backs the case for investing in social capital as a route to tangible improvements in people’s lives and livelihoods. This increased resilience came even despite severe floods in 2015. The big takeaways for me were:

Trust emerged as a key factor in the success or failure for the MOs. This speaks to the findings on much of our governance work, in both conflict and non-conflict affected areas. In this case activities on trust were not an explicit focus, but they certainly will be in all future projects.

Better access to government services correlates with the areas where there are stronger MOs. But which comes first? Did the MOs use collective power to secure better services, or were

they stronger in the first place because they had stronger social capital from better education, healthcare, nutrition etc? Or are there influential individuals in those villages that are able to both secure government services and build a strong MO? Possibly a combination of factors at play, but it begs the question, what do we do about building MOs in areas where there are little or no services? Is it just more intense support that is needed or a new design altogether, do we in fact have to deliver those services for a while before we get into longer term development work? Or will that cause damage by interfering with the model where the government provides services and the community hold them to account over those services?

they stronger in the first place because they had stronger social capital from better education, healthcare, nutrition etc? Or are there influential individuals in those villages that are able to both secure government services and build a strong MO? Possibly a combination of factors at play, but it begs the question, what do we do about building MOs in areas where there are little or no services? Is it just more intense support that is needed or a new design altogether, do we in fact have to deliver those services for a while before we get into longer term development work? Or will that cause damage by interfering with the model where the government provides services and the community hold them to account over those services?A lack of enabling environment – that is, a local government that is willing and able to engage with communities, was a key constraint – the government was very closed at the time in this region. This meant that all our efforts went into building the demand side (organizing people to make demands on government). But when the political opening came along, the project benefited from a change in policy when local development funds started to flow towards the project end – and the MOs were ready with their resilience action plans and in many cases able to secure funds for their priorities. So what do we do in closed areas such as this? Just invest in the demand side ready for when things open up to engage with the government? Or invest time in trying to get a breakthrough? How to do a cost benefit analysis on such a dilemma?

Women in leadership increased after the exit, to more than 40% 18 months on, and only 13% of those asked in the community expressed distrust in women’s leadership capacity. These are decent results, but it’s difficult to work out why this happened, even with this detailed level of review. Was it down to good gender programming (we certainly invested a lot of time and energy in this), or did external factors such as the success of Aung San Suu Kyi as a female role model have an effect?

MO membership massively increased after the project finished, and the MOs came together and in some cases, secured donor funding. Why did people continue to join and decide to collaborate? Was it a coping mechanism once the NGO support stopped? Is the project closure in fact a good thing, exiting before dependency sets in?

What would it take to move the Hopeful MOs to a stage of Maturing MOs? (Bearing in mind these typologies had pretty high standards in this review). Is it more time, better design, or just the level of enabling environment or access to services that would make the difference? Or does it all come down to individuals with leadership and social capital at the village level?

As ever, community development done well is resource intensive and it is difficult to demonstrate cost effectiveness. But if you’re going to invest in such intense processes, the key is to get that initial investment as right as possible, demonstrate the value for money where you can – and build in space for adaptation as you ‘learn by doing’ and/or conditions change. The review has given us tonnes of insights for future programme design on success factors and risk factors in local governance and resilience building. The question now is how to institutionalize such knowledge so that learning reviews do indeed feed into the future?

January 22, 2017

Links I Liked

Now President Trump is US tweeter in chief, I’m going to have to start running more screen grabs in these round- ups. Here he is taking on author Isaac Marion. 21,000 RTs and counting….

ups. Here he is taking on author Isaac Marion. 21,000 RTs and counting….

How has your country changed since the year of your birth? Fun interactive, which also allows you to compare with progress in other countries

How to write a blogpost from your journal article in 11 easy steps. Patrick Dunleavy’s post was the most read in 2016 on the excellent LSE Impact blog and is good advice for non-academic bloggers too.

ODI’s 10 recommendations on how to influence policy with research

Hats off to whichever genius at The Economist came up with this graph of Japanese GDP v tuna prices.

Hats off to whichever genius at The Economist came up with this graph of Japanese GDP v tuna prices.

Killer fact (literally). Massive new WHO study finds tobacco costs the world economy over $1 trillion a year. More than 1.1 billion people smoke

In the spirit of getting out of our filter bubble, check out this 2m trailer for anti-aid film Poverty, Inc. Listen first (you might agree with some of it), then critique.

Systems thinking: a cautionary tale (cats in Borneo). Nice illustration

January 19, 2017

5 Straws to Clutch/Reasons to be Cheerful on US presidential inauguration day

Someone asked me to try and write something positive today, so here goes. As  President Obama told his daughters, the only thing that’s the end of the world is the end of the world. This ain’t it. So (channelling Ian Dury), here are some reasons to be cheerful:

President Obama told his daughters, the only thing that’s the end of the world is the end of the world. This ain’t it. So (channelling Ian Dury), here are some reasons to be cheerful:

The US is deeply federal: to a Brit, it’s striking how many of the big decisions are taken at state and municipal level. Lots of really interesting initiatives on climate change, living wage etc – the cities and states will be the incubators of new ideas and practices for future decades.

Trump is not Putin: the new President does not appear to have some master plan for hollowing out democratic institutions. He may not even have the stamina for the long slog of trying to get decisions through the system.

Trump supporters are not a monolith: 60m people voted for Trump for a whole range of reasons. Inequality and economic exclusion; objections to Obama and his policies; a backlash against ‘political correctness’ and being made to feel guilty by condescending liberals and, yes, some nasty anti-immigrant and anti-minority sentiments. That coalition is likely to fracture pretty soon under the pressures of being in office.

History is on the side of progressive change: the US is becoming ever-more diverse; out there among the public, norms are shifting in good directions (as well as some bad) on a whole range of issues. A politics built on nostalgia has a fast approaching sell-by date.

Reality exists: post-truth politics can only win temporary victories, because there is a reality out there that will come back to bite it.

Actually, it probably isn’t

So what are poverty-fighting activists to do? I am not a US citizen, and cannot fully grasp the grief, anger and despair of many of my American friends, but here are some thoughts, partly arising out of conversations on my US trip just after the election.

Defend the institutions: I thought Obama’s last major speech was absolutely spot on. The job of citizens in the coming years is to defend democratic institutions – rule of law, freedom of the press.

Think about the long game: progressives have been so fixated on short term wins – policies, spending decisions, laws – that they failed to notice the longer term alienation and disillusionment with politics and politicians, leaving the path open to a particular brand of populism. We need to reengage with the long term.

Norms and narratives: that means strengthening our understanding and use of stories and narratives. We have become policy wonks, whose idea of a good ‘product’ is a ‘bad shit, facty facty’ policy paper (as one Aussie critic branded them). We’re not in a post-truth world; it’s just that truth is much more than a compilation of statistics. We need to get back to constructing more powerful and persuasive narratives and myths, as Alex Evans argues in his new book. We need to learn to speak to the heart again, not just the head.

We need to reconnect with citizens: there’s a saying I love about liberation theology in Latin Ameria and its ‘preferential option for the poor’: ‘the Catholics opted for the poor, but the poor opted for the Evangelical Protestants’. On 9th November, I felt like I had accidentally become a member of an elite that had lost touch with the hearts and minds of ordinary citizens. We need to turn off the social media, get out and talk to people, reconnect (check out the comments on my recent post on the filter bubble for some great ideas about how to do this).

Rant over. Well I feel better, even if you don’t.

Other related posts: Theories of Change for a political downturn; Pre-US trip thoughts on post-election strategy

And here’s the incomparable Ian Dury:

January 18, 2017

Why Davos should be talking about Disability

In what I think had better be the last blog for Davos, Jodie Thorpe, IDS and

In what I think had better be the last blog for Davos, Jodie Thorpe, IDS and  Yogesh Ghore, Coady International Institute present important new research on a rising issue on the development agenda

Yogesh Ghore, Coady International Institute present important new research on a rising issue on the development agenda

Can markets include and benefit some of the most marginalized people on earth, such as persons with disabilities? The leaders of government, business and third sector organizations gathered in Davos this week should be asking themselves that question – for economic reasons, because those facing extreme marginalisation represent a substantial pool of human potential; for reasons of social cohesion and stability; and primarily for equity reasons, in line with the global commitment to ‘leave no one behind’.

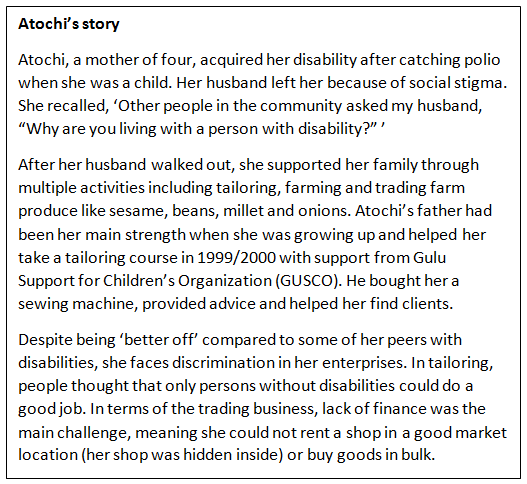

A group of us at IDS, the Coady International Institute and ADD International have spent the last 18 months trying to answer this question – speaking with dozens of initiatives, identifying 22 promising examples of market-based approaches and collaborating with peer researchers in Uganda. By peer researchers, we mean persons with disabilities who have been gathering and analyzing the life stories of other persons with disabilities. Here’s what we have learned:

1, The most marginalised face both extreme poverty – part of the 800 million living on less than $1.90 per day – plus social isolation due to disability, as well as gender, caste, ethnicity and other factors that leave individuals or groups in positions of low status and power. They are at the bottom of the economic pyramid where incomes are low and insecure, they have only very basic assets (e.g. less than 0.5 ha of land) and skills (e.g. primary education), and face prejudice and discrimination. The most excluded survive outside the economy, through subsistence livelihoods, precarious informal activities like begging and/or reliance on family members.

2. Excluded groups and those supporting them are finding different ways to overcome economic exclusion. Our typology identifies four entry points that offer ‘ladders’ for marginalized people to climb the economic pyramid or lower the barriers to entry: making the most of existing skills or assets, organising collectively amongst the most marginalised, coordinating with others in the market, and engaging employers and others to remove physical and attitudinal barriers in the workplace. A fifth entry point, which we called ‘a leg up’, reflects that for some, social protection and livelihood development support is needed to first get a foot on the ladder before they can pursue opportunities.

exclusion. Our typology identifies four entry points that offer ‘ladders’ for marginalized people to climb the economic pyramid or lower the barriers to entry: making the most of existing skills or assets, organising collectively amongst the most marginalised, coordinating with others in the market, and engaging employers and others to remove physical and attitudinal barriers in the workplace. A fifth entry point, which we called ‘a leg up’, reflects that for some, social protection and livelihood development support is needed to first get a foot on the ladder before they can pursue opportunities.

3. Economic exclusion is not the only challenge. Often extremely marginalized people cannot access these economic ladders and entry points —let alone climb them – due to social circumstances and discrimination. These can mean, for example, that people with disability are excluded from the benefits of collective action through member-based organisations, due to physical and communication barriers, as well as cultural norms and biases.

These multiple dimensions of marginalization came across very strongly in the 102 life stories and livelihoods mapping conducted as part of our field work with persons with disabilities in Uganda. While, in the absence of required support systems, the nature and extent of impairment affected how people were able to make a living, discrimination due to their disability significantly amplified that marginalization. For example, access to finance was a challenge for persons with disabilities  not necessarily due to their impairment, but because they were perceived as ‘high risk’, even in community-based models such as the village savings and loans associations (VSLAs). As a consequence, persons with disabilities were mostly engaged in low-risk, micro-scale activities in the informal sector, resulting in a vicious cycle of low return and low investments.

not necessarily due to their impairment, but because they were perceived as ‘high risk’, even in community-based models such as the village savings and loans associations (VSLAs). As a consequence, persons with disabilities were mostly engaged in low-risk, micro-scale activities in the informal sector, resulting in a vicious cycle of low return and low investments.

The analysis of our 22 examples revealed how people overcome such exclusion, emphasizing elements which go beyond hard or tangible factors like assets and skills, training, inputs, finance, or laws, rules and standards. These ‘softer’ elements include strong family and friendship bonds that give people self-esteem and confidence, as well as social or community support networks and integration in cooperatives or self-help groups.

4. Marginalised people have limited resources to cope with shocks such as illness and deaths in the family, extreme weather and food scarcity. They hedge their bets by investing time in diverse and often non-market livelihood strategies: building social capital in family networks, carrying out unpaid work, and gathering and subsistence food production, which are as or more important than markets. While better incomes can build coping capacity, they also increase exposure to risk if loans are taken, scarce assets invested or diversity of livelihoods is reduced.

Minimising risk and building resilience are therefore important pre-conditions to opening up market opportunities to very marginalised people, and preventing them from subsequently falling back into poverty. In addition to social protection, the market-based approaches we identified focused on diversifying livelihoods, including a mix of subsistence and market activities, diversified markets to lower dependence, and asset accumulation through self-help groups or village savings and loans associations.

5. Commercial enterprises have not been at the forefront of these approaches, which have largely been the province of member-based organizations (MBOs), social enterprises, NGOs and government or donor programmes. However, a key message from our ground level panel in Uganda – consisting of peer researchers, private sector, government and civil society organisations – was that solutions need actions from a broad range of stakeholders. These include marginalized people who succeed despite these obstacles, as well as community networks and organisations of persons with disabilities, government agencies which provide health and education services and assistive devices, and business people who make decisions about market facilities and can help change attitudes and overcome stigma. By their actions, government, business and third sector leaders and their organizations can shape markets to remove barriers to entry, and create circumstances that support those facing extreme marginalization to reach and benefit from them.

January 17, 2017

A Song for Davos: your chance to vote on best song on inequality

Twitter definitely beats work. On Monday, Oxfam’s Max Lawson kicked off a discussion on the best song about economic inequality, which got enough candidates for an impromptu ‘Song for Davos’ competition – check these out and vote.

Creedence Clearwater Revival, Fortunate Son [Max Lawson]

Bob Marley, Them Belly Full [me, with post on Marley v IMF]

Motorhead, Eat the Rich [Phil Evans]

Juliani (Kenyan rapper, more here), Utawala [Jenny Ricks]

UB40, 1 in 10 [Phil Evans]

Tracy Chapman: Mountains O’ Things [Max Lawson]

The Reverend Peyton’s Big Damn Band, Everything’s Raising but the Wages [Mark Furness]

Abba, Money Money Money [Max again]

Afraid I ruled out a couple of other suggestions because they weren’t strictly about economic inequality, were piss takes (sorry Spinal Tap) or were just bad. Anyway, there’s only so many Facebook ads any human being can bear.

So please vote for your favourite, and if you think I’ve missed a really good one suggest it in the comments because, who knows, we may do this in a more organized fashion for Davos 2018 – also, this lot feels pretty dated even to me, so can we have some more recent songs please?

Over to you – you’ve each got 3 votes

Note: There is a poll embedded within this post, please visit the site to participate in this post's poll.

January 16, 2017

Davos & Inequality Continued: What does an alternative economic vision for the future look like?

Deborah Hardoon, who really ought to be resting on her laurels after her report for Davos went  viral yesterday, springs to the defence of (the right kind of) economics.

viral yesterday, springs to the defence of (the right kind of) economics.

Nerd Alert. As a student of economics, I always found the technical aspects of the subject deeply satisfying. Getting to the ‘right’ answer using algebra and statistics, solving ‘proofs’ and finding that stable equilibrium. Bliss.

But what’s always been more fascinating is that economics is a social science, it’s about real places, human behaviours and complex environments and governance systems. This is messy and diverse, so in order to derive textbook ready models, principles and theorems, economics has had to cut through the mess to make simple standard assumptions about the world we live in. ‘People’, with different characters, abilities and oportunities are replaced by identical ultility maximising individuals. Echo chambers, propaganda and manipulative marketing are replaced by the assumption that all consumers and businesses have perfect information about each other.

Put the messiness back in and the models soon start to look a whole lot less satisfying. Economic growth doesn’t always trickle down to benefit the poorest. When people receive higher wages, they tend not to work fewer hours (as the backwards bending labour supply curve would suggest). Production is not just a function of capital and labor, but also environmental resources and impacts,not to mention unpaid labour.

And of course, hardly any economists saw the financial crisis coming… The reputation of the ‘dismal science’ is facing further derision. Last week Andy Haldane the chief economist at the Bank of England said that economic forecasting was in crisis.

And of course, hardly any economists saw the financial crisis coming… The reputation of the ‘dismal science’ is facing further derision. Last week Andy Haldane the chief economist at the Bank of England said that economic forecasting was in crisis.

But before we throw the baby out with the bathwater (has anyone ever actually done that?) and deem all economists irrelevant and useless, I think it helps to be more specific about the ‘problem’ with economics and economists today.

So let’s start with why at least some economics deserves the current kicking. If we look at economic orthodoxy, there is a lot that Oxfam can take aim at.

Take the captain of economic measures, GDP and GDP growth. As a measure, it completely ignores who get’s what from the economy – people living in poverty can be netted off by high incomes elsewhere. It is indifferent to the kind of production (cigarettes or vegetables) that’s growing or what’s happening to the environment. Yet it remains at the forefront of economic decision making and it’s the first economic indicator listed in the back of The Economist every week, despite a recent (April 2016) special edition that highlighted its flaws and limitations.

who get’s what from the economy – people living in poverty can be netted off by high incomes elsewhere. It is indifferent to the kind of production (cigarettes or vegetables) that’s growing or what’s happening to the environment. Yet it remains at the forefront of economic decision making and it’s the first economic indicator listed in the back of The Economist every week, despite a recent (April 2016) special edition that highlighted its flaws and limitations.

Neoliberal economics promotes markets as the most efficient way to allocate resources, as the forces of supply and demand fight it out, free from distorting government intervention, and the most efficient price and output is achieved. But unfettered ‘markets’ also allow medicines to be priced out of reach of the most vulnerable, bankers to take risks which destabilise the global economy, more investments in dirty energy at a time when we know our environment can’t handle the impacts.

But despite the flack that economics is getting today, I still think it’s a pretty exciting, relevant and dynamic subject– if you look outside of that orthodoxy. Innovative academic Institutions and think tanks are promoting new ways of using economics to understand our current reality. This is a reality which includes a warming climate, societies that are built on patriarchy and value that can’t be monetised. Degrowth, alternative economics and new economic paradigms – the ideas are flowing, the mutations are proliferating. Students are challenging their professors in the rethinking economics movement.

Last month 13 of the world’s leading economists, including Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz and four former Chief Economists of the World Bank, released a statement that said ‘It is now evident that some of the recommendations of more traditional economics were not valid’ and proposed an alternative set of principles for organising economies.

At Oxfam, Kate Raworth published work on the donut economics in 2012, which brought together the need to meet the basics for people whilst respecting the planet boundaries. She left Oxfam to turn it into a book, which is out in April – it could be very influential. Last week my colleague Katherine Trebeck, who has been exploring New Economic Paradigms for some years, published (with two other authors) Tackling Timorous Economics, using Scotland as an example but with much wider application of how to manage our economies better.

At Oxfam, Kate Raworth published work on the donut economics in 2012, which brought together the need to meet the basics for people whilst respecting the planet boundaries. She left Oxfam to turn it into a book, which is out in April – it could be very influential. Last week my colleague Katherine Trebeck, who has been exploring New Economic Paradigms for some years, published (with two other authors) Tackling Timorous Economics, using Scotland as an example but with much wider application of how to manage our economies better.

And yesterday we published ‘An Economy for the 99%’, timed to coincide with the week that the super rich and powerful convene in Davos for the annual World Economic Forum. First and foremost, the report highlights the extreme level of economic inequality, by way of a killer stat that is great clickbait: 8 men now have the same amount of wealth as the bottom half of the world’s population. Get beyond the headline and you will read our analysis of how we got to such a perverse, unequal and unfair situation. We unpack the assumptions on which governments, businesses and individuals base decisions, find them to be false and driving our societies and our planet off a cliff.

Inequality is increasingly recognised as a problem in our societies. We saw in the UK referendum on the UK and the election of Donald Trump in the US, how people are feeling left behind, deriding experts and blaming immigrants. But what we need now are solutions, not scapegoats. And economics, which attempts to unpack, model and understand the world in which we live can continue to be helpful, provided we embrace an understanding of where it has gone wrong in the past. In this report we provide a compelling alternative to the economic orthodoxy – a human economy, where people and planet are put before profits.

January 15, 2017

8 men now own the same as the poorest half of the world: the Davos killer fact just got more deadly

It’s Davos this week, which means it’s time for Oxfam’s latest global ‘killer fact’ on extreme

2016 numbers: now a golfcart should do it

inequality. Since our first calculation in 2014, these have helped get inequality onto the agenda of the global leaders assembled in Switzerland. This year, the grabber of any headlines not devoted to the US presidential inauguration on Friday is that it’s worse than we thought. Last year it was 62 people who owned the same as the poorest half of the world. This year it is down to 8. Just 8 men. Have as much wealth as 3.6 billion poor men, women and children. Think about that for a moment, before getting geeky and carrying on with the rest of this post.

Every year, there are also regular attempts at rubbishing the new stat. An admirably nerdy box in Oxfam’s new paper for Davos both explains the origins of the new number (better data) and addresses the expected counterarguments.

And here’s a golfcart

‘In January 2014, Oxfam calculated that just 85 people had the same amount of wealth as the bottom half of humanity. This was based on data on the net wealth of the richest individuals from Forbes and data on the global wealth distribution from Credit Suisse. For the past three years, we have been tracking these data sources to understand how the global wealth distribution is evolving. In the Credit Suisse report of October 2015, the richest 1% had the same amount of wealth as the other 99%.

This year we find that the wealth of the bottom 50% of the global population was lower than previously estimated, and it takes just eight individuals to equal their total wealth holdings. Every year, Credit Suisse acquires new and better data sources with which to estimate the global wealth distribution: its latest report shows both that there is more debt in the very poorest group and fewer assets in the 30–50% percentiles of the global population. Last year it was estimated that the cumulative share of wealth of the poorest 50% was 0.7%; this year it is 0.2%.

Table 1: Share of wealth across the poorest 50% of the global population

Poorest 10%

2%

3

4

5

Poorest 50%

2015 calculations

-0.3

0.1

0.1

0.3

0.5

0.7

2015 UPDATED

-0.4

0.0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.2

2016 data

-0.4

0.0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.2

The inequality of wealth that these calculations illustrate has attracted a lot of attention, both to the obscene level of inequality they expose and to the underlying data and the calculations themselves. Two common challenges are heard. First, that the poorest people are in net debt, but these people may be income-rich thanks to well-functioning credit markets (think of the indebted Harvard graduate). However, in terms of population, this group is insignificant at the aggregate global level, where 70% of people in the bottom 50% live in low-income countries. The total net debt of the bottom 50% of the global population is also just 0.4% of overall global wealth, or $1.1 trillion. If you ignore the net debt, the wealth of the bottom 50% is $1.5 trillion. It still takes just 56 of the wealthiest individuals to equal the wealth of this group.

The second challenge is that changes over time of net wealth can be due to exchange-rate fluctuations, which matter little to people who want to use their wealth domestically. As the Credit Suisse reports in US$, it is of course true that wealth held in other currencies must be converted to US$. Indeed, wealth in the UK declined by $1.5 trillion over the past year due to the decline in the value of Sterling. However, exchange-rate fluctuations cannot explain the long-run persistent  wealth inequality which Credit Suisse shows (using current exchange rates): the bottom 50% have never had more than 1.5% of total wealth since 2000, and the richest 1% have never had less than 46%. Given the importance of globally traded capital in total wealth stocks, exchange rates remain an appropriate way to convert between currencies.’

wealth inequality which Credit Suisse shows (using current exchange rates): the bottom 50% have never had more than 1.5% of total wealth since 2000, and the richest 1% have never had less than 46%. Given the importance of globally traded capital in total wealth stocks, exchange rates remain an appropriate way to convert between currencies.’

The paper has a larger aim, setting out some initial thinking on the constituent elements of a ‘human economy approach’ that can turn around both inequality and other public bads created by prevailing orthodoxies. Here are the headlines:

A human economy would see national governments accountable to the 99%, and playing a more interventionist role in their economies to make them fairer and more sustainable.

A human economy would see national governments cooperate to effectively fix global problems such as tax dodging, climate change and other environmental harm.

A human economy would see businesses designed in ways that increase prosperity for all, and contribute to a sustainable future.

A human economy would not tolerate the extreme concentration of wealth or poverty, and the gap between rich and poor would be far smaller.

A human economy would work equally as well for women as it does for men.

A human economy would ensure that advances in technology are actively steered to be to the benefit of everyone, rather than meaning job losses for workers or more wealth for those who own the businesses.

A human economy would ensure an environmentally sustainable future by breaking free of fossil fuels and embarking on a rapid and just transition to renewable energy.

A human economy would see progress measured by what actually matters, not just by GDP. This would include women’s unpaid care, and the impact of our economies on the planet.

January 12, 2017

Preaching to the Converted and the Path to Unlearning: this week’s random conversations

Had some interesting if random discussions this week – I work from home a lot, and then get far too excited when I actually end up in a room with interesting people. Two thoughts (among many) seem worth capturing:

Preaching to the converted: This is something we’re not supposed to do – waste of time all  agreeing with each other, right? We need to get out there and engage with the Other, the heathen, the unenlightened etc. Well (channelling Samuel L Jackson in Pulp Fiction), allow me to retort. Most Imams and priests spend the vast majority of their time preaching to the converted, and they seem to have a pretty solid business model. Preaching to the converted plays an essential role in consolidating commitment and attendance, both inspiring and training activists, it builds a sense of belonging and engagement (depending on whether the preacher is any good, of course). However, it may be worth drawing a distinction between preaching to the converted and ‘preaching to the choir’, which I take to be the US variant of the phrase. Preaching to the choir – as in your hard core, totally committed activists, may indeed be a bit of a waste of time – NGO full timers telling each other stuff they already know (‘agreeing violently’) springs to mind.

agreeing with each other, right? We need to get out there and engage with the Other, the heathen, the unenlightened etc. Well (channelling Samuel L Jackson in Pulp Fiction), allow me to retort. Most Imams and priests spend the vast majority of their time preaching to the converted, and they seem to have a pretty solid business model. Preaching to the converted plays an essential role in consolidating commitment and attendance, both inspiring and training activists, it builds a sense of belonging and engagement (depending on whether the preacher is any good, of course). However, it may be worth drawing a distinction between preaching to the converted and ‘preaching to the choir’, which I take to be the US variant of the phrase. Preaching to the choir – as in your hard core, totally committed activists, may indeed be a bit of a waste of time – NGO full timers telling each other stuff they already know (‘agreeing violently’) springs to mind.

But where does that leave the discussion on getting out of our filter bubbles? Sticking with the religious analogy, should we all be doing 90% preaching to the converted, and 10% trying to proselytize among the heathen? Or should we be looking for hard core missionaries to live outside the bubble full time? Who/what would they look like in political terms?

How does Unlearning happen? Next up, if we are going to try and get aid agencies to ‘do development differently’, we will be asking people who have had logframe thinking drummed into them for decades to start behaving in a drastically different fashion. To caricature (hey, it’s what I do…) people who count beans, tick boxes, hit deadlines and implement The Plan will suddenly be expected to be cool, entrepreneurial, improvising risk takers and surfers of unpredictable events.

In many cases, I have serious doubts that this is possible – we may just have to employ different kinds of people as jobs fall vacant (change happens one funeral at a time etc). But if we are going to try, then existing staff and partners will have to ‘unlearn’ a lot of what has gone before.

In many cases, I have serious doubts that this is possible – we may just have to employ different kinds of people as jobs fall vacant (change happens one funeral at a time etc). But if we are going to try, then existing staff and partners will have to ‘unlearn’ a lot of what has gone before.

But how does unlearning even happen? Thinking about it in my own life, I can identify a few processes which lead to me jettisoning ways of thinking and working:

Humiliation and defeat: Here’s how I learned to let go and devolve power. Newly arrived at Oxfam, I was sent on a deeply traumatic management training course at an outward bound centre in the Lake District. One of the exercises was a giant outdoor chess match. Each team had a couple of people moving the pieces around, and a couple of remote ‘managers’ who were told they were in charge. They communicated with the players via a walkie talkie, which was tied to a tree, and a runner who carried messages from the walkie talkie to the players. I was a manager, and we duly set up a dummy chessboard and sent messages via the runner (who in our case was Jo Cox, during her period at Oxfam). As the delayed results filtered back via Jo, we watched horrified as our side was destroyed by the opposition. We later found that the enemy manager (Kate Raworth) had used the walkie talkie to ask her players if they were good at chess. When they said ‘yes’, she said ‘right, over to you’ and went and had a cup of tea. She had no problem letting go/devolving power, whereas it had never occurred to me. It was a lesson I’ll never forget. I could tell a lot of other stories along these lines – regularly making a fool of myself seems to be my prime personal driver of change……

Success stories on the ground: But screwing up is not the only way; there’s nothing like the demonstration effect of seeming something innovative working on the ground – Chukua Hatua in Tanzania, TajWSS in Tajikistan, Community Protection Committees in DRC

Paradigm shifting overall narratives: I get ridiculously excited by big picture books that shift my way of thinking – Robert Chambers, Ha Joon Chang, Eric Beinhocker, Donella Meadows, Jerry and Monique Sternin, Portfolios of the Poor. They not only critique a standard way of thinking, but offer a convincing and original alternative.

In terms of promoting new ways of thinking and working, it feels like lots is happening on (2) and (3), but what about (1)? Do we need to think about how to engender a personal sense of crisis, shock, fear or whatever before people will really abandon tried and tested (but failed) approaches? How to encourage those moments in a reasonably humane fashion?

January 11, 2017

A 3-fold theory of social change (and some great quotes on complexity, ambiguity and dreaming)

Sometimes a paper is worth blogging about just for the quotes. Here are the best from a 2016 update of Doug Reeler’s ‘A Three-Fold Theory of Social Change’:

“I would not give a fig for the simplicity on this side of complexity. But I would give my life for the simplicity on the other side.” Oliver Wendell Holmes

“Whosoever wishes to know about the world must learn about it in its particular details. Knowledge

Heraklitus trying to work it all out

is not intelligence. In searching for the truth be ready for the unexpected. Change alone is unchanging. The same road goes both up and down. The beginning of a circle is also its end. Not I, but the world says it: all is one. And yet everything comes in season.” Heraklietos of Ephesos, 500 B.C

“We do not grow absolutely, chronologically. We grow sometimes in one dimension, and not in another; unevenly. We grow partially. We are relative. We are mature in one realm, childish in another. The past, present, and future mingle and pull us backward, forward, or fix us in the present. We are made up of layers, cells, constellations.” Anais Nin

“The truth is that our finest moments are most likely to occur when we are feeling deeply uncomfortable, unhappy, or unfulfilled. For it is only in such moments, propelled by our discomfort, that we are likely to step out of our ruts and start searching for different ways or truer answers.” M. Scott Peck

‘Reformers mistakenly believe that change can be achieved through brute sanity’ George Bernard Shaw

“Without leaps of imagination, or dreaming, we lose the excitement of possibilities. Dreaming after all, is a form of planning.” Gloria Steinem

But the paper is also really good. It sets out 3 types of change and argues that, although reality is often messier, it is worth thinking of them as a sequence through which a typical organization moves:

‘a) Emergent change: A new organisation, or a new department in a larger organisation, begins in its pioneering phase, emerging experimentally as it finds its identity and purpose, learning its way into the future by doing, by creative trial-and-error, often running informally by unwritten rules, held together by the will and personality of its pioneer often in an intense and personal atmosphere.

b) Transformative change: As with seedlings, growth of new organisations can be rapid, but at some point the organisation enters its first developmental crisis where the quantity and complexity of the work, and the number of staff, outgrow the capacity of the pioneer or the informal systems to effectively manage. Often the new generation of staff call for visible procedures, systems and policies, for accountable organisation, but this call is resisted by those who have been there since the early days, not least the pioneer who feels a threat to the power he or she has become used to and known for – “things worked so well like this in the past, we just have to get people on board”. But a transformation is required that enables a letting go of that informality, an unlearning of the unwritten rules, paving the way for a new regime. This letting go is not simply an instrumental process of installing new systems but about a transfer of power and a shift in culture. It meets resistance which must be faced before the new phase of change can take centre stage.

unwritten rules, paving the way for a new regime. This letting go is not simply an instrumental process of installing new systems but about a transfer of power and a shift in culture. It meets resistance which must be faced before the new phase of change can take centre stage.

c) Projectable change: The new regime, working in a new, more rational phase, is marked by a more visible and conscious projecting of visions and strategizing and planning the way to get there, enabled by visible, written systems and policies that support a new kind of work.

Until the next developmental crisis requiring more transformation.’

Which reminds me somewhat of the early stages of the forest cycle (see graphic) described by Jean Boulton. What that adds is the sclerosis and rigidity that affect organizations once they have become fixed in the ‘projectable change’ phase, and how that leads to meltdowns and crises that begin the process anew.

I also really liked the final message of the mercifully brief (18 page) paper, which is published by South Africa’s excellent Community Development Resource Association, and aimed at donors, governments and on-the-ground social change organizations:

‘Change cannot be engineered but can only be cultivated. Seeds must be chosen whose fruits not only suit the taste of the eaters but also to suit the soil in which they are planted, the conditions for  their fruition. Processes of change, whether emergent, transformative or projectable, are already there, moving or latent, and must be read and worked with as natural processes inherent to the lives and cultures of people themselves. This kind of orientation, applied respectfully and skilfully, may indeed yield the impact and sustainability that is so desperately sought. Perhaps then our obsession with accountability may be allayed, not because we will have learnt how to better measure impact, but because we will have learnt to practise better, to read change more accurately and work with it more effectively.’

their fruition. Processes of change, whether emergent, transformative or projectable, are already there, moving or latent, and must be read and worked with as natural processes inherent to the lives and cultures of people themselves. This kind of orientation, applied respectfully and skilfully, may indeed yield the impact and sustainability that is so desperately sought. Perhaps then our obsession with accountability may be allayed, not because we will have learnt how to better measure impact, but because we will have learnt to practise better, to read change more accurately and work with it more effectively.’

January 10, 2017

Is the Anti-Politics machine still a good critique of the aid business?

Just been re-reading a great 6 page summary of James Ferguson’s 1994 classic critique of the aid industry, The Anti-Politics Machine. Read this and ask yourself, apart from the grating use of the term ‘Third World’, how much has changed?

industry, The Anti-Politics Machine. Read this and ask yourself, apart from the grating use of the term ‘Third World’, how much has changed?

‘Any question of the form ‘what is to be done?’ demands first of all an answer to the question, ‘By whom?’ The ‘development’ discourse, and a great deal of policy science, tends to answer this question in a utopian way by saying ‘Given an all-powerful and benevolent policy-making apparatus, what should it do to advance the interests of its poor citizens?’

This question is worse than meaningless. In practice, it acts to disguise what are, in fact, highly partial and interested interventions as universal, disinterested and inherently benevolent. If the question ‘What is to be done?’ has any sense, it is as a real-world tactic, not a utopian ethnics.

The question is often put in the form ‘What should they do?’, with the ‘they’ being not very helpfully specified as ‘Lesotho’ or ‘the Basotho’. When ‘developers’ speak of such a collectivity what they mean is usually the government. But the government of Lesotho is not identical with the people who live in Lesotho, nor is it in any of the established senses ‘representative’ of that collectivity. As in most countries, the government is a relatively small clique with narrow interests. There is little point in asking what such entrenched and extractive elites should do in order to empower the poor. Their own structural position makes it clear that they would be the last ones to undertake such a project.

Perhaps the ‘they’ in ‘what should they do?’ means ‘the people’. But again the people are not an undifferentiated mass. There is not one question – What is to be done? – but hundreds: What should the mineworkers do? What should the abandoned old women do? And so on. It seems presumptuous to offer prescriptions here. Toiling miners and abandoned old women know the tactics proper to their situations far better than any expert does. If there is advice to be given about what ‘they’ should do, it will not be dictating general political strategy or giving a general answer to the question ‘what is to be done?’ (which can only be determined by those doing the resisting) but answering specific, localized, tactical questions.

If the question is, on the other hand, ‘What should we do?’, it has to be specified, which ‘we’? If ‘we’ means ‘development’ agencies or governments of the West, the implied subject of the question falsely implies a collective project for bringing about the empowerment of the poor. Whatever good or ill may be accomplished by these agencies, nothing about their general mode of operation would justify a belief in such a collective ‘we’ defined by a political programme of empowerment.

If the question is, on the other hand, ‘What should we do?’, it has to be specified, which ‘we’? If ‘we’ means ‘development’ agencies or governments of the West, the implied subject of the question falsely implies a collective project for bringing about the empowerment of the poor. Whatever good or ill may be accomplished by these agencies, nothing about their general mode of operation would justify a belief in such a collective ‘we’ defined by a political programme of empowerment.

For some Westerners, there is, however, a more productive way of posing the question ‘what should we do?’ That is, ‘What should we intellectuals working in or concerned about the Third World do?’ To the extent that there are common political values and a real ‘we’ group, this becomes a real question. The answer, however is more difficult.

Should those with specialized knowledge provide advice to ‘development’ agencies who seem hungry for it and ready to act on it? These agencies seek only the kind of advice they can take. One ‘developer’ asked my advice on what his country could do ‘to help these people’. When I suggested that his government might contemplate sanctions against apartheid, he replied with predictable irritation, ‘No, no! I mean development!’ The only advice accepted is about how to ‘do development’ better. There is a ready ear for criticisms of ‘bad development projects’, only so long as these are followed up with calls for ‘good development projects’. Yet the agencies who plan and implement such projects – agencies like the World Bank, USAID and the government of Lesotho – are not really the sort of social actors that are very likely to advance the empowerment of the poor.

Such an obvious conclusion makes many uncomfortable. It seems to them to imply hopelessness; as if to suggest that the answer the question ‘What is to be done?’ is: ‘Nothing’. Yet this conclusion does not follow. The state is not the only game in town, and the choice is not between ‘getting one’s hands dirty by participating in or trying to reform development projects’ and ‘living in an ivory tower’. Change comes when, as Michel Foucault says, ‘critique has played out in the real, not when reformers have realized their ideas.’

For Westerners, one of the most important forms of engagement is simply the political participation in one’s own society that is appropriate to any citizen. This is perhaps, particularly true for citizens of a country like the US, where one of the most important jobs for ‘experts’ is combating imperialist policies.’

23 years on, is this sceptical view of the politics of aid becoming more justified? Should I stop seeking allies and common ground in USAID or the World Bank? Is all that stuff about adaptive management, empowerment and ‘doing development differently’ either PR spin or wishful thinking? Or has something substantial moved on (and if so, why)? I’d be interested in your thoughts.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers