Duncan Green's Blog, page 128

December 15, 2016

On webinars, prayer and ‘transformational development': an hour with World Vision

I’m becoming a big fan of webinars. I can slump in front of the computer at  home, slurping a coffee, give a presentation on the book (Open Access helps – no need to try and get people to buy copies, just download the pdf after the session), then sit back and listen to the ensuing conversation. On Wednesday it was 50 or so World Vision staff across the world, discussing ‘Transformational Development’ on a very user-friendly Webex platform. Some impressions:

home, slurping a coffee, give a presentation on the book (Open Access helps – no need to try and get people to buy copies, just download the pdf after the session), then sit back and listen to the ensuing conversation. On Wednesday it was 50 or so World Vision staff across the world, discussing ‘Transformational Development’ on a very user-friendly Webex platform. Some impressions:

It’s pretty disconcerting for a lifelong atheist like me to start a webinar by listening to a prayer, but actually I found it quite calming – an aid to reflection. Equally striking were the references for the need to stop and listen (to God; to poor people), rather than let ourselves be consumed by the reflex busy-ness of activism, which stops us listening to anyone.

cake wins every time

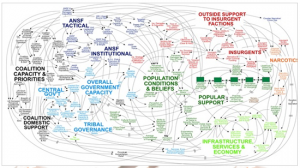

Webex allows funky instant polls – asked after my 20m pitch to vote on whether WV inclines in its work more towards the cake (linear programming) or the Afghan map (systems thinking), participants came down 3:1 for the cake. Top quote ‘cakes are just theories – we need to adapt them as we go’.

The panel (WV staff from Burundi, Zambia and Cambodia) discussed what all this means on the ground. A few impressions:

WV is deeply embedded in communities, with a commitment to listening to their voices and opinions. In Cambodia they have introduced a ‘community reflection process’ – an ‘annual pause button’, whereby communities stand back and reflect on their progress and the contribution of government and aid partners (not just WV). They write it up in their own language (not as obvious as it seems), and then share it with neighbouring communities (often triggering a discussion on shared priorities) as well as government and NGOs.

I was impressed, but also a bit sceptical – how do you shift power and incentives to make sure that the results of such reflections are taken seriously by INGO staff? How do you genuinely ‘hand over the stick’? It also got me thinking about Oxfam’s model, which is based on working through local partner organizations, often NGOs, rather than much direct contact with communities. The downside is that we are more easily insulated from the

Words, words, words

messiness of reality (and so able to escape into the relatively ordered, linear world of projects and partnerships), whereas WV can’t help but be aware of the complex, unpredictable nature of reality. The upside is that working via partners hopefully dilutes the power imbalance created by the funding relationship. Our partners are embedded in real communities, and perhaps better able to keep us at arm’s length, when we start trying to impose the wrong ideas or solutions.

On the ground process increasingly involves WV engaging with the state at multiple levels, and non state actors such as traditional leaders – WV is learning to ‘dance with the system’. The trouble with dancing with the system is that it can produce some awkward dance partners/moves. In Zimbabwe, it’s ended up with parents agreeing to pay for school textbooks because their engagement with the Ministry of Education made it clear that the state has no budget for it. How does that fit with potential organizational red lines – a commitment to equity or right to education? In Burundi, communities raised alcoholism and witchcraft as their two biggest concerns but ‘we don’t have a project for that’.

The conversation also highlighted something which emerged in my recent paper on donor theories of change in fragile states – the need to separate out a Theory of Action (by change agents) from a Theory of (endogenous) Change. On a good day, INGOs consult deeply and listen to communities about their priorities and the problems they face. But what happens next? I fear that activists are either too busy to lift their heads up and see what is happening all around them, or (worse) reserve for themselves the role of acting to address those problems. That means that the discussion becomes all about ‘what can we do’, rather than ‘how is the system changing/likely to change without us?’ By treating the community/village/sector as an essentially static set of players and problems on which change agents act, we ignore the actual dynamics of change. That means that our own interventions are less likely to fit with those dynamics and so less likely to have impact.

The conversation also highlighted something which emerged in my recent paper on donor theories of change in fragile states – the need to separate out a Theory of Action (by change agents) from a Theory of (endogenous) Change. On a good day, INGOs consult deeply and listen to communities about their priorities and the problems they face. But what happens next? I fear that activists are either too busy to lift their heads up and see what is happening all around them, or (worse) reserve for themselves the role of acting to address those problems. That means that the discussion becomes all about ‘what can we do’, rather than ‘how is the system changing/likely to change without us?’ By treating the community/village/sector as an essentially static set of players and problems on which change agents act, we ignore the actual dynamics of change. That means that our own interventions are less likely to fit with those dynamics and so less likely to have impact.

At the end of the seminar, WV collected the comments, identified common themes and got the participants to rank them in order of importance. Here’s the winning candidates for things that WV should ‘Continue’, ‘Stop’ and ‘Start’

Continue:

Implementing based on community input and participation

Taking time to understand power dynamics and build relationships

Stop:

Rushing community processes to tick boxes

Applying project models without adequate adaptation

Start:

Gather the evidence – hear the voice of the poor and vulnerable

More intentional iterative learning and adaptation

Fascinating and productive. More webinars please!

More more info on WV’s work see this guide to local community engagement, check out their field staff blog on transformational development, or watch this 6m video

December 14, 2016

Why is Africa’s Civil Society under Siege?

Oxfam’s Ross Clarke (Governance and Legal Adviser )

Oxfam’s Ross Clarke (Governance and Legal Adviser )  and Desire Assogbavi (Resident Representative & Head of Office, Oxfam International Liaison Office to the African Union) introduce a new analysis of the threats to African civil society

and Desire Assogbavi (Resident Representative & Head of Office, Oxfam International Liaison Office to the African Union) introduce a new analysis of the threats to African civil society

After years on the margins of the mainstream development agenda, addressing civic space is finally getting the attention it deserves. If the number of policy initiatives, conferences and campaigns is any indication, creating the conditions for democratic participation, citizen activism and effective civil society organisations (CSOs) is again a priority of several donors and agencies.

In large part the renewed emphasis on civic space reflects a worsening situation on the ground, especially across the African continent. As Oxfam and CCP-AU’s new Policy Brief – ‘Putting Citizen Voice at the Centre of Development: Challenging Shrinking Civic Space across Africa’ (here in French) – makes clear, 29 restrictive laws have been introduced in Sub-Saharan Africa since 2012. The impact of these laws (well documented by Civicus, ICNL and others) is that mobilising around specific causes, speaking out and holding governments to account is getting increasingly difficult and dangerous. Even the African Union (AU), so long a positive example of civil society participation, and despite the commitment to being people-driven in its Constitutive Act, has recently restricted CSO attendance at AU Summits.

The new brief highlights two main drivers behind the crackdown. The first is  the impact of the security agenda and efforts to combat violent extremism. Increasingly, governments across the region have reacted to real and perceived security threats by asserting more control and restrictions over civic space. CSOs have been viewed with particular suspicion as potential cover for extremist groups, despite a lack of evidence to back this up. Vaguely worded laws allow police to disperse peaceful protests and funding is becoming all the more difficult as banks are increasingly reluctant to channel funds given perceived security risks. While safeguarding security is paramount, it is easily misused as an excuse to target CSOs or stifle independent voices.

the impact of the security agenda and efforts to combat violent extremism. Increasingly, governments across the region have reacted to real and perceived security threats by asserting more control and restrictions over civic space. CSOs have been viewed with particular suspicion as potential cover for extremist groups, despite a lack of evidence to back this up. Vaguely worded laws allow police to disperse peaceful protests and funding is becoming all the more difficult as banks are increasingly reluctant to channel funds given perceived security risks. While safeguarding security is paramount, it is easily misused as an excuse to target CSOs or stifle independent voices.

The second driver is the overwhelming priority placed on national unity and economic progress over space for citizen participation. In the ‘developmental state’ critical voices are often cast as a threat to national interests. When activists criticise government policy, they are often labelled anti-development or politically motivated. Yet without critical voices how can we speak truth to power and hold them accountable?

More broadly, the rise of China and the economic progress of Ethiopia and Rwanda offer an alternative – and in some eyes more effective – approach to delivering national prosperity, building social cohesion and defining citizen-state relations. As European and U.S. democracies struggle on economic and political fronts, do they still represent an ideal to be aspired to? The answer has become far more complicated in recent years.

More broadly, the rise of China and the economic progress of Ethiopia and Rwanda offer an alternative – and in some eyes more effective – approach to delivering national prosperity, building social cohesion and defining citizen-state relations. As European and U.S. democracies struggle on economic and political fronts, do they still represent an ideal to be aspired to? The answer has become far more complicated in recent years.

Yet tackling vested interests and resolving the continent’s most intractable challenges – persistent poverty and rising income inequality, political capture of state resources, youth unemployment, adapting to a changing climate, the list goes on – requires independent civic actors to be actively engaged in crafting and achieving solutions. Governments and the private sector cannot do it alone.

We are not arguing that CSOs are faultless or should be above scrutiny. The paper highlights the importance of civil society putting its own house in order. Reasonable regulation is legitimate, necessary and can enhance effectiveness and accountability in the sector. But any regulation must not be overly burdensome, driven by political motives or designed to stifle independent voices – and currently that is exactly what is happening in many countries. Above all, civil society must model the change it seeks. This requires greater transparency, accountability and reduced power imbalances between civil society actors.

Addressing closing civic space is not a self-serving exercise focused on Oxfam and our NGO friends. It encompasses the diverse range of activists, unions, social movements, religious and sporting groups that make up a vibrant civil society. Fundamentally, it is about our rights as citizens to participate in public life, whether individually or collectively, voice our interests and concerns, and where necessary be a check on power. These are values worth protecting. If the political shockwaves of 2016 are any indication, protecting the hard won human rights gains of recent decades may depend on it.

December 13, 2016

What can Harry Potter, Lord of the Rings and the Matrix teach us about how change happens?

Chatting to academics in the US last week, we swapped notes on the merits of using shared cultural references to convey some of the key ideas around how change happens. They act as a short cut, allowing subtle, nuanced ideas to be discussed on the basis of a large pool of common knowledge. You need to avoid the pitfalls of cultural imperialism, of course (so religious texts are tricky), but thanks to social media and Hollywood, there are some pretty universal narratives to build on. I picked up a couple in the book, but failed to capitalise on some of the recent blockbusters – Game of Thrones, Hunger Games etc. Can you help?

using shared cultural references to convey some of the key ideas around how change happens. They act as a short cut, allowing subtle, nuanced ideas to be discussed on the basis of a large pool of common knowledge. You need to avoid the pitfalls of cultural imperialism, of course (so religious texts are tricky), but thanks to social media and Hollywood, there are some pretty universal narratives to build on. I picked up a couple in the book, but failed to capitalise on some of the recent blockbusters – Game of Thrones, Hunger Games etc. Can you help?

The Power and Systems Approach (see summary, right) set out in the book talks about the kinds of people we need to be to work in complex systems, and the kinds of questions we need to ask. In terms of popular culture, I came up with the following (please note, not all of these are entirely serious):

In terms of ‘How we think/feel/work’, we have 3 out of 4:

Curiosity = The Wire: ‘Bunk, a dissolute but brilliant detective, advises a new recruit that the key to success is cultivating ‘soft eyes’, learning to spot the important clues that lie in your peripheral vision or that you weren’t looking for. Being a good observer is harder than it sounds. It’s easy to see what we are  looking for, but much harder to notice and register the unexpected, or the evidence that contradicts our assumptions.’

looking for, but much harder to notice and register the unexpected, or the evidence that contradicts our assumptions.’

Humility= Harry Potter (or the opposite of Hermione, anyway): ‘In Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, when Hermione sets up an ‘Elf Liberation Front’ to free the house elves who serve the wizard community. The house elves are horrified—no-one had asked them if they wanted to be ‘liberated’, which to them looks very much like being unemployed. Hermione didn’t consult the elves; she merely assumed she knew what was right for them. She really needed a proper theory of change.’

Multiple perspectives, unusual suspects = Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring is really a classic multi-stakeholder initiative in which the different

Multistakeholder Initiative, Middle Earth style

capacities and skillsets of the participants lead to a stronger overall entity.

So what’s the popular narrative that brings alive the importance of the one remaining element – reflexivity: awareness of our own personal impact on the system we are trying to describe and change?

The second part of the Power and Systems Approach is about ‘The questions we ask (and keep asking)’. I need a bit more help here, as I’ve only got one at the moment:

Power = The Matrix: Power is the underlying matrix of development. Making  power visible so that we can think about how it can be redistributed more fairly is like Neo coming to see the Matrix and acquiring superpowers (ahem…)

power visible so that we can think about how it can be redistributed more fairly is like Neo coming to see the Matrix and acquiring superpowers (ahem…)

Oddly, I never quoted West Wing in the book, perhaps because it applies to almost everything (as does South Park, it seems).

Now it’s your turn: what popular narratives can help with the remaining elements of the PSA?

The importance of changing norms as well as more tangible things like policies and spending

The value of successful precedents, both historical and current

The need for feedback loops and course corrections

Remember, the references have to be universally recognizable to a student age range, which probably means they have to be in TV/movie format as well as books.

December 12, 2016

On theories of change, what are the differences between playing offence and defence?

Unsurprisingly, in this year of Brexit and US elections, I’ve been thinking  about how to stop bad stuff happening. While they are doubtless desperately looking for silver linings in a year of defeats, progressive movements are likely to spend a good part of the next few years defending good things from political assault. So what is the same/different about defence and offence when it comes to theories of change?

about how to stop bad stuff happening. While they are doubtless desperately looking for silver linings in a year of defeats, progressive movements are likely to spend a good part of the next few years defending good things from political assault. So what is the same/different about defence and offence when it comes to theories of change?

Similarities include the role of critical junctures (get ready to seize the windows of opportunity provided by scandals and screw ups – and rest assured, they will come); the importance of alliances, especially building links with unusual suspects currently in the opposition camp; understanding the system and power analysis. Some might also agree with Jack Dempsey’s advice (below) that the best form of defence is attack, so stick to what you know. But what might be different?

I’ve already argued that one implication is that activists need to move on from an exclusive focus on stats and numbers to become more skilled in using metaphors and narratives.

Stopping bad stuff happening lends itself to tactics of delay and doubt – you’re trying to stop bad change taking place until its current window of opportunity closes. That could involve:

Weapons of the weak (to use the wonderful title of James C. Scott’s book on ‘Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance’), including ‘‘foot-dragging, evasion, false compliance, pilfering, feigned ignorance, slander and sabotage’. Wonderful language, and sounds like a potential set of tactics for aid workers and civil servants resisting efforts to make them do dumb stuff.

Sowing Doubt: in a now infamous 1969 memo, an executive at the R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company helpfully explained “Doubt is our product since it is the best means of competing with the ‘body of fact’ that exists in the mind of the general public.” More generally, the first stage in blocking change is to undermine its dominance of the hearts and minds of those in power – for example the ‘Adjustment with a Human Face’ authors who took on the Washington Consensus at its height in the 1980s, beginning the intellectual fightback against a damaging orthodoxy that seemed almost unassailable at the time.

Sowing Doubt: in a now infamous 1969 memo, an executive at the R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company helpfully explained “Doubt is our product since it is the best means of competing with the ‘body of fact’ that exists in the mind of the general public.” More generally, the first stage in blocking change is to undermine its dominance of the hearts and minds of those in power – for example the ‘Adjustment with a Human Face’ authors who took on the Washington Consensus at its height in the 1980s, beginning the intellectual fightback against a damaging orthodoxy that seemed almost unassailable at the time.

Running from the Bear: two people are running from a bear. One hurriedly puts on trainers. ‘Are you crazy?’ asks the other, ‘there’s no way you can run faster than a bear!’ I don’t have to, comes the reply, I just have to run faster than you. Only a limited number of policy reversals can take place in the window of opportunity following a victory – how to make sure yours isn’t one of them? Amid the chaos and lack of planning that characterize both Brexit and the Trump victory, there may be an argument for lying low rather than

Relevant for advocacy as well as boxing?

raising your voice. You may just get through the reform window unharmed.

Find common ground: One of the alarming things for progressives in both the Brexit and US campaigns was hearing people say ‘I’m angry about inequality and the fat cats getting fatter, and that’s why I’m voting for Trump/Brexit’. There’s clearly some common ground to be found, but we need to look hard, and understand the issues and values underpinning the coalitions that voted. Then we can set about building bridges (not walls), thereby both strengthening the coalition for progressive change, and weakening its opponents.

Going long term. Learn from Chicago University. At the height of Keynesianism, the ‘Chicago Boys’ dug in for the long haul, taking control of a few university departments and creating generations of monetarist and free market disciples who would go on to lead the counter revolution a generation later when they came to power. What would be the progressive equivalent?

That could involve shifting the point of engagement away from a temporarily unreachable national government – municipal and state governments have traditionally provided the incubators for the next wave of radical ideas (eg Bolsa Familia in Brazil). Time to dig in at local level?

Other suggestions?

December 11, 2016

Links I Liked

Social Wealth Funds, publicly owned, that pursue social good & reduce (rather than exacerbate) inequality. A smart proposal from Stewart Lansley

Talking of wealth, you can always rely on the FT magazine’s ‘How to Spend It’ column to answer the really

Damen Sea Axe yacht support vessel, from €16m, with Amels superyacht | Image: AMELS

pressing questions of the age: ‘when your superyacht is too small, you are no longer expected to buy a bigger one. Instead, you just get another one. Your second yacht carries all the toys and tenders, helicopters and submarines, extra staff and spare crew that clutter up the mother ship and get in the way of the guests.’ h/t the tragically yachtless Max Lawson

Nice overview of the hugely hyped Brac graduation scheme, which seems well on its way to magic bullet status. Can a microfinance-style takedown be far behind? Apparently not.

Five questions we should be asking about impact of UK aid. Measured response from Oxfam’s Mark Goldring (full disclosure: he’s my boss) on DFID’s recent series of aid reviews

Why Lord of the Flies is the perfect 2016 Christmas gift for 2016. This makes me want to reread

And the results are in for the best and worst charity videos of 2016, aka (respectively) the golden radiator and rusty radiator awards. The Guardian shows the 3 best and 3 worst with commentary. By popular vote, this is the worst of the lot, edging out other shockers from Save the Children Netherlands and World Vision Australia. Step forward Compassion International for the catwalk of shame.

and this is how to get it totally, wonderfully right. The winner, from the International HIV/AIDS Alliance, and props to the other finalists, Plan International UK and Amnesty Poland.

December 8, 2016

How do we choose the most promising theory of change? Building on the context-intervention 2×2

One of the slides from my standard HCH presentation that resonated most during the many conversations and book launches in the US was the 2×2 on which kinds of interventions are compatible with different contexts. I first blogged about this a year ago, when the 2×2 emerged during a workshop of aid wonks, but the recent discussions have added some nice extra ideas to what this diagram does/doesn’t tell us:

Top Right: If you are confident about both your understanding of the context, and ability to run the intervention, you may be in the top right quadrant, where traditional linear approaches can work. Get out logframes and project toolkits. But Harvard’s Salimah Samji worries about ‘false quadrant syndrome’, whereby everyone thinks they’re in the top right, heaves a sigh of relief and says ‘great, we can just carry on as usual’. But what about hubris – they don’t know what they don’t know? What are the signals that you’re confidence is unwarranted and you need to look at the other quadrants? One might be if unexpected stuff keeps happening all around you (suggesting your confidence on context was unwarranted), or if your project keeps going wrong (ditto on intervention).

Top Left: This feels like where a lot of the adaptive management crowd are headed (see yesterday’s post). If you’re doing cash transfers in Somalia, and people have to keep fleeing the violence, the key is to have rapid feedback and response, enabling you to move your operations to where they have run to – you probably don’t need to rethink the merits of cash transfers.

What’s noticeable is how much more comfortable and active the aid business is above the line than below it. Below the line corresponds to aid peeps acknowledging uncertainty over their interventions – it seems the call for humility, especially about our own role, is a tough one for a lot of organizations. Adaptive Management is dipping a toe in the water of the  bottom right, through things like PDIA (Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation). But I see no-one coming to the table on the bottom left (‘you don’t know where you are + you don’t know what you’re doing’). That’s where positive deviance comes into its own, but no-one seems to be doing that, probably because it is all about seeing where the system has come up with its own solutions, so no role for experts, or for spending loads of money, so where’s the incentives? Yet I increasingly think this could be one of the big wins for the aid industry. Anyone doing it?

bottom right, through things like PDIA (Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation). But I see no-one coming to the table on the bottom left (‘you don’t know where you are + you don’t know what you’re doing’). That’s where positive deviance comes into its own, but no-one seems to be doing that, probably because it is all about seeing where the system has come up with its own solutions, so no role for experts, or for spending loads of money, so where’s the incentives? Yet I increasingly think this could be one of the big wins for the aid industry. Anyone doing it?

Oxfam MEL (monitoring, evaluation and learning) guru Mary Sue Smiaroski raises the interesting point that decent MEL should help push people between quadrants. Eg finding that your confidence is baseless, or after a couple of rounds of iterations, deciding you have found a good bet, promoting it to top right and scaling up.

Matthew Spencer, Oxfam’s new Director of Policy and Campaigns, was interesting in locating different campaign styles in different quadrants. He sees Oxfam’s campaign as bottom right – lots of trying things out and testing,  before moving up to top right and rolling out the big guns. Avaaz and change.org are top left – single interventions with fast feedback. He sees bottom left as inhabited by lots of small organizations campaigning away on different issues and occasionally throwing up big wins, as in the UK’s Modern Slavery movement.

before moving up to top right and rolling out the big guns. Avaaz and change.org are top left – single interventions with fast feedback. He sees bottom left as inhabited by lots of small organizations campaigning away on different issues and occasionally throwing up big wins, as in the UK’s Modern Slavery movement.

The 2×2 is limited in scope – it describes the potential role of outsiders, not what local change looks like, but what I like about it is that it provides a way to discuss the merits of lots of different approaches, traditional, emerging and deeply unconventional, rather than proposing a single magic bullet.

Thoughts?

How do we chose the most promising theory of change? Building on the context-intervention 2×2

One of the slides from my standard HCH presentation that resonated most during the many conversations and book launches in the US was the 2×2 on which kinds of interventions are compatible with different contexts. I first blogged about this a year ago, when the 2×2 emerged during a workshop of aid wonks, but the recent discussions have added some nice extra ideas to what this diagram does/doesn’t tell us:

Top Right: If you are confident about both your understanding of the context, and ability to run the intervention, you may be in the top right quadrant, where traditional linear approaches can work. Get out logframes and project toolkits. But Harvard’s Salimah Samji worries about ‘false quadrant syndrome’, whereby everyone thinks they’re in the top right, heaves a sigh of relief and says ‘great, we can just carry on as usual’. But what about hubris – they don’t know what they don’t know? What are the signals that you’re confidence is unwarranted and you need to look at the other quadrants? One might be if unexpected stuff keeps happening all around you (suggesting your confidence on context was unwarranted), or if your project keeps going wrong (ditto on intervention).

Top Left: This feels like where a lot of the adaptive management crowd are headed (see yesterday’s post). If you’re doing cash transfers in Somalia, and people have to keep fleeing the violence, the key is to have rapid feedback and response, enabling you to move your operations to where they have run to – you probably don’t need to rethink the merits of cash transfers.

What’s noticeable is how much more comfortable and active the aid business is above the line than below it. Below the line corresponds to aid peeps acknowledging uncertainty over their interventions – it seems the call for humility, especially about our own role, is a tough one for a lot of organizations. Adaptive Management is dipping a toe in the water of the  bottom right, through things like PDIA (Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation). But I see no-one coming to the table on the bottom left (‘you don’t know where you are + you don’t know what you’re doing’). That’s where positive deviance comes into its own, but no-one seems to be doing that, probably because it is all about seeing where the system has come up with its own solutions, so no role for experts, or for spending loads of money, so where’s the incentives? Yet I increasingly think this could be one of the big wins for the aid industry. Anyone doing it?

bottom right, through things like PDIA (Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation). But I see no-one coming to the table on the bottom left (‘you don’t know where you are + you don’t know what you’re doing’). That’s where positive deviance comes into its own, but no-one seems to be doing that, probably because it is all about seeing where the system has come up with its own solutions, so no role for experts, or for spending loads of money, so where’s the incentives? Yet I increasingly think this could be one of the big wins for the aid industry. Anyone doing it?

Oxfam MEL (monitoring, evaluation and learning) guru Mary Sue Smiaroski raises the interesting point that decent MEL should help push people between quadrants. Eg finding that your confidence is baseless, or after a couple of rounds of iterations, deciding you have found a good bet, promoting it to top right and scaling up.

Matthew Spencer, Oxfam’s new Director of Policy and Campaigns, was interesting in locating different campaign styles in different quadrants. He sees Oxfam’s campaign as bottom right – lots of trying things out and testing,  before moving up to top right and rolling out the big guns. Avaaz and change.org are top left – single interventions with fast feedback. He sees bottom left as inhabited by lots of small organizations campaigning away on different issues and occasionally throwing up big wins, as in the UK’s Modern Slavery movement.

before moving up to top right and rolling out the big guns. Avaaz and change.org are top left – single interventions with fast feedback. He sees bottom left as inhabited by lots of small organizations campaigning away on different issues and occasionally throwing up big wins, as in the UK’s Modern Slavery movement.

The 2×2 is limited in scope – it describes the potential role of outsiders, not what local change looks like, but what I like about it is that it provides a way to discuss the merits of lots of different approaches, traditional, emerging and deeply unconventional, rather than proposing a single magic bullet.

Thoughts?

December 7, 2016

Adaptive Management looks like it’s here to stay. Here’s why that matters.

The past two weeks in Washington, New York and Boston have been intense,

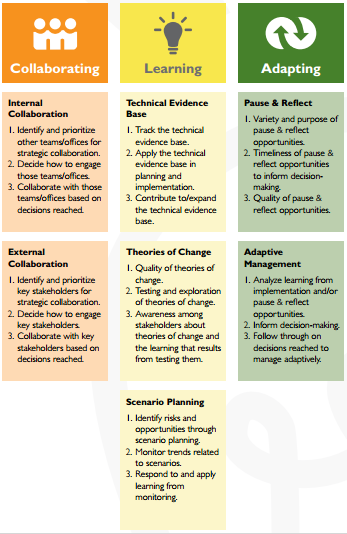

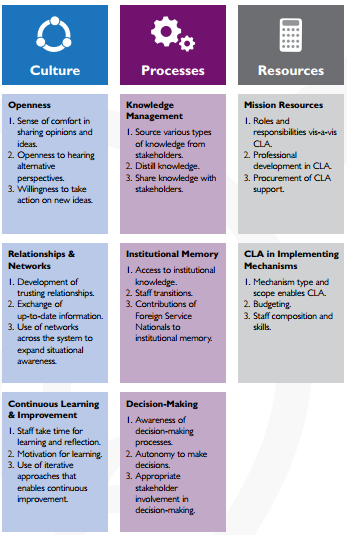

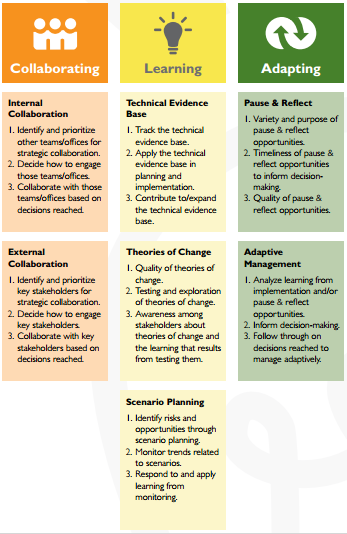

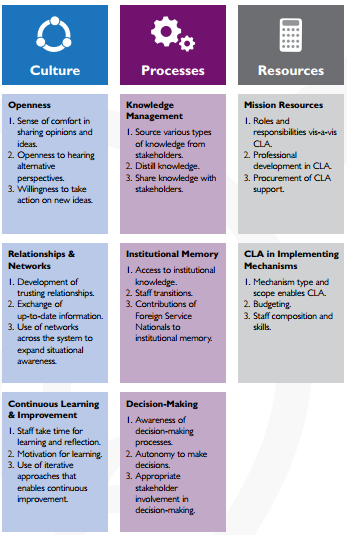

USAID’s ‘Collaborating, Learning and Adapting’ Framework

leaving lots of unpacking for the blog. Let’s start with the numerous discussions on ‘adaptive management’ (AM), which seems to where the big aid agencies have found a point of entry into the whole ‘Doing Development Differently’ debate.

I spent a day with USAID and came away with a sense that AM has now got into its bloodstream and feels like considerably more than a passing fad. USAID is now pushing adaptive management down through the plumbing, requiring it as part of its funding procedures (not a very bottom up approach, it’s true, but when the pied paper plays, everyone dances). Its ‘Program Cycle Operational Policy’ – i.e. the new ‘guidelines to ‘implementing partners’ applying for funding, has as one of its 3 overall requirements: ‘Learning from performance monitoring, evaluations, and other relevant sources of information to make course corrections as needed and inform future programming.’ A handy two pager fleshes this out as an infographic, covering both the programme cycle, and the broader ‘enabling conditions’ (see below) for making AM more than just another buzzword. This feels like a big deal, given that USAID is (so far) the largest bilateral donor by miles, and seems way ahead of what I’ve seen in other bilaterals (DFID and co, feel free to set me straight on that).

USAID AM program cycle

Matt Andrews in his book The Limits of Institutional Reform in Development sets out a series of stages that institutional reform passes through:

Deinstitutionalization: encourage the growing discussion on the problems of the current model

Preinstitutionalization: groups begin innovating in search of alternative logics, involving ‘distributive agents’ (eg low ranking civil servants) to demonstrate feasibility

Theorization: proposed new institutions are explained to the broader community, needing a ‘compelling message about change.’

Diffusion: as more ‘distributive agents’ pick it up, a new consensus emerges

Reinstitutionalization: legitimacy (hegemony) is achieved. Reformers can all go off to the pub.

With these guidelines, USAID appears to be entering that final stage, whereas many others (including Oxfam) are still at the earlier stages, with skirmishing between AM supporters and sceptics, old school logframers or value for money/results people.

Some further thoughts emerged during the numerous conversations:

How to distinguish between adaptive and indecisive? Course corrections could, after all, merely be a sign of someone who keeps changing their mind; ‘Failing Fast’ might show that you are rubbish at your job, not a budding venture capitalist. Funders and political supporters will need some kind of quality assurance if they are to buy into this, and one option might be a ‘third party audit’ function – someone external who accompanies a programme and can give an independent view on the quality of analysis and decision making. Sounds a bit like the way The Asia Foundation has hired a

USAID AM Enabling Conditions

number of academics to accompany its country advocacy teams in recent years in a process it calls ‘strategy testing’.

Where’s the Evidence: In the end AM is only going to take hold if there is compelling evidence that it produces better results than the alternatives. That needs to be more rigorous and convincing than random praise-singing of iconic AM projects. One interesting approach is how AM and non-AM programmes respond to shocks – the Ebola crisis provided just such a ‘natural experiment’ in Sierra Leone, where IRC was able to compare how flexible and inflexible funding arrangements responded to events (not surprisingly, flexible did better). More please.

History: when old lags hear the hype about AM, they tend to roll their eyes and say ‘seen it all before’. Not good enough – could they then please go away and do some serious analysis of previous aid reform movements, and work out why some have had lasting impact, while others have faded away? I also have a suspicion that new thinking in aid is subject to a process of attrition, whereby it is slowly dumbed down and shorn of its more exciting aspects, as it becomes just another set of tick boxes. We probably do have to reinvent the wheel – recover the original excitement of earlier reform movements, perhaps even around the same ideas, with different vocabulary to make things seem new and funky. Is that such a terrible price to pay?

Are other trends in aid compatible with AM? In particular the payment by results movement just got a big boost from DFID’s Multilateral Aid Review, which plans to spend up to 30% of its funding to UN humanitarian and development agencies via PbR. In theory PbR should be compatible with adaptive management, in that it allows recipients to do what they like, as long as they get the eventual results. In practice, there are signs that it is not quite so simple, with PbR being used more to pass the buck on risk, than to liberate implementers to be more entrepreneurial.

Are other trends in aid compatible with AM? In particular the payment by results movement just got a big boost from DFID’s Multilateral Aid Review, which plans to spend up to 30% of its funding to UN humanitarian and development agencies via PbR. In theory PbR should be compatible with adaptive management, in that it allows recipients to do what they like, as long as they get the eventual results. In practice, there are signs that it is not quite so simple, with PbR being used more to pass the buck on risk, than to liberate implementers to be more entrepreneurial.

And one lingering concern: AM could become just a technique for better programming, without any discussion of power or politics. I guess that would be better than dumb linear programming, but still, it would lose a lot in terms of understanding the system, or pursuing worthwhile change that ‘expands the freedoms to be and to do’ in Amartya Sen’s indispensable definition of development. How do we guard against that depoliticisation?

More post-US ramblings to follow.

Adaptive Management looks like it’s hear to stay. Here’s why that matters.

The past two weeks in Washington, New York and Boston have been intense,

USAID’s ‘Collaborating, Learning and Adapting’ Framework

leaving lots of unpacking for the blog. Let’s start with the numerous discussions on ‘adaptive management’ (AM), which seems to where the big aid agencies have found a point of entry into the whole ‘Doing Development Differently’ debate.

I spent a day with USAID and came away with a sense that AM has now got into its bloodstream and feels like considerably more than a passing fad. USAID is now pushing adaptive management down through the plumbing, requiring it as part of its funding procedures (not a very bottom up approach, it’s true, but when the pied paper plays, everyone dances). Its ‘Program Cycle Operational Policy’ – i.e. the new ‘guidelines to ‘implementing partners’ applying for funding, has as one of its 3 overall requirements: ‘Learning from performance monitoring, evaluations, and other relevant sources of information to make course corrections as needed and inform future programming.’ A handy two pager fleshes this out as an infographic, covering both the programme cycle, and the broader ‘enabling conditions’ (see below) for making AM more than just another buzzword. This feels like a big deal, given that USAID is (so far) the largest bilateral donor by miles, and seems way ahead of what I’ve seen in other bilaterals (DFID and co, feel free to set me straight on that).

USAID AM program cycle

Matt Andrews in his book The Limits of Institutional Reform in Development sets out a series of stages that institutional reform passes through:

Deinstitutionalization: encourage the growing discussion on the problems of the current model

Preinstitutionalization: groups begin innovating in search of alternative logics, involving ‘distributive agents’ (eg low ranking civil servants) to demonstrate feasibility

Theorization: proposed new institutions are explained to the broader community, needing a ‘compelling message about change.’

Diffusion: as more ‘distributive agents’ pick it up, a new consensus emerges

Reinstitutionalization: legitimacy (hegemony) is achieved. Reformers can all go off to the pub.

With these guidelines, USAID appears to be entering that final stage, whereas many others (including Oxfam) are still at the earlier stages, with skirmishing between AM supporters and sceptics, old school logframers or value for money/results people.

Some further thoughts emerged during the numerous conversations:

How to distinguish between adaptive and indecisive? Course corrections could, after all, merely be a sign of someone who keeps changing their mind; ‘Failing Fast’ might show that you are rubbish at your job, not a budding venture capitalist. Funders and political supporters will need some kind of quality assurance if they are to buy into this, and one option might be a ‘third party audit’ function – someone external who accompanies a programme and can give an independent view on the quality of analysis and decision making. Sounds a bit like the way The Asia Foundation has hired a

USAID AM Enabling Conditions

number of academics to accompany its country advocacy teams in recent years in a process it calls ‘strategy testing’.

Where’s the Evidence: In the end AM is only going to take hold if there is compelling evidence that it produces better results than the alternatives. That needs to be more rigorous and convincing than random praise-singing of iconic AM projects. One interesting approach is how AM and non-AM programmes respond to shocks – the Ebola crisis provided just such a ‘natural experiment’ in Sierra Leone, where IRC was able to compare how flexible and inflexible funding arrangements responded to events (not surprisingly, flexible did better). More please.

History: when old lags hear the hype about AM, they tend to roll their eyes and say ‘seen it all before’. Not good enough – could they then please go away and do some serious analysis of previous aid reform movements, and work out why some have had lasting impact, while others have faded away? I also have a suspicion that new thinking in aid is subject to a process of attrition, whereby it is slowly dumbed down and shorn of its more exciting aspects, as it becomes just another set of tick boxes. We probably do have to reinvent the wheel – recover the original excitement of earlier reform movements, perhaps even around the same ideas, with different vocabulary to make things seem new and funky. Is that such a terrible price to pay?

Are other trends in aid compatible with AM? In particular the payment by results movement just got a big boost from DFID’s Multilateral Aid Review, which plans to spend up to 30% of its funding to UN humanitarian and development agencies via PbR. In theory PbR should be compatible with adaptive management, in that it allows recipients to do what they like, as long as they get the eventual results. In practice, there are signs that it is not quite so simple, with PbR being used more to pass the buck on risk, than to liberate implementers to be more entrepreneurial.

Are other trends in aid compatible with AM? In particular the payment by results movement just got a big boost from DFID’s Multilateral Aid Review, which plans to spend up to 30% of its funding to UN humanitarian and development agencies via PbR. In theory PbR should be compatible with adaptive management, in that it allows recipients to do what they like, as long as they get the eventual results. In practice, there are signs that it is not quite so simple, with PbR being used more to pass the buck on risk, than to liberate implementers to be more entrepreneurial.

And one lingering concern: AM could become just a technique for better programming, without any discussion of power or politics. I guess that would be better than dumb linear programming, but still, it would lose a lot in terms of understanding the system, or pursuing worthwhile change that ‘expands the freedoms to be and to do’ in Amartya Sen’s indispensable definition of development. How do we guard against that depoliticisation?

More post-US ramblings to follow.

December 6, 2016

A lesson on power and the abstruse (or a love-peeve relationship Part 2)

Duly provoked by yesterday’s assault on IDS’ use of language, John Gaventa responds with a really nice story/rebuttal

As ever, we are delighted to see Duncan Green’s interesting and incisive blog on the new IDS Bulletin on Power, Poverty and Inequality.

In talking about what he calls his ‘love – peeve’ relationship with IDS, Duncan raises important questions of language in how we discuss power, and challenges us over what he calls “abstruse language and reluctance to commit to the ever-elusive ‘so whats?’’

Let me respond with a story – one that taught me never to underestimate the ability of people to decipher language, no matter how abstract, and to use analytical frames to figure out and take action for themselves.

Years ago my Oxford DPhil thesis, later to become the book Power and Powerlessness, focused on the power of the mining industry in a poor, remote part of the Appalachian Region in Kentucky and Tennessee. The first chapter of the book was pretty heavy going – as PhD theses often are. It included a complex scheme of the ‘Power of A over B’, across three dimensions of power. Looking back it was about as ‘abstruse’ as it gets, and in retrospect even I sometimes have a hard time understanding what I was trying to say!

But a few years after the book was published, I had a call from a group of miners, farmers, housewives and others in one of the towns featured in the book, who asked if I could come and discuss the book with them. I was a bit surprised as this was an area with extremely low levels of education and literacy, not known for its liberal book clubs. But not only had they bought copies of the book, they had sussed out the complex diagram.

But a few years after the book was published, I had a call from a group of miners, farmers, housewives and others in one of the towns featured in the book, who asked if I could come and discuss the book with them. I was a bit surprised as this was an area with extremely low levels of education and literacy, not known for its liberal book clubs. But not only had they bought copies of the book, they had sussed out the complex diagram.

Figuring out the ‘so-what’s’

They had used the framework to plot a strategy to form an alternative local political party, the ‘Time for a Change Party’, which went on to depose the corrupt mayor and bring in a reform candidate. That introductory chapter of what Duncan would call ‘abstruse language’ had as much impact as any other more popular piece I have written, and more to the point, the people who read it had the capacity, skill and will to decide the ‘so what’ for themselves. They didn’t need me to figure it out for them.

As a young researcher, this experience brought a home life-long lesson: never assume what language is useful to whom, nor think that people don’t have the capacity to figure out how analysis can inform action for themselves. In fact, they may be better at it than we are.

And Duncan, if a group of miners and farmers in Appalachia can plough  through my dense DPhil thesis, then don’t be so hard on a far more user-friendly, open access IDS Bulletin! There are lots of gems in there still to be uncovered about how to analyse and challenge power, which we are confident people will mine for themselves.

through my dense DPhil thesis, then don’t be so hard on a far more user-friendly, open access IDS Bulletin! There are lots of gems in there still to be uncovered about how to analyse and challenge power, which we are confident people will mine for themselves.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers