Duncan Green's Blog, page 131

November 7, 2016

Climate Change: Meeting sea level rise by raising the land

As the COP 22 meeting on climate change gets under way in Marrakech, Joseph Hanlon

, Manoj Roy

and David

Hulme

introduce their new book on climate change and Bangladesh

Community groups in coastal Bangladesh have shown that the land can be raised to match sea level rise. Their success has been hard fought, initially contested by aid agencies, engineers and the police. But they have won over policy makers and scientists who realise this will be important in the struggle to adapt to climate change.

Most of Bangladesh is a huge delta built by major rivers flowing down from the Himalayas. The land is rich and this densely populated country is self-sufficient in rice. But it is also flat and subject to devastating floods and cyclones, which will be made much worse by climate change. Since independence in 1971, Bangladesh has made substantial efforts to reduce the damage done by the dramatic disasters. And since the disasters will be made worse by climate change, for three decades Bangladeshi scientists, politicians and communities have been working to adapt to climate  change and to press industrialised countries to curb greenhouse gas emissions. We tell this story in our new book “Bangladesh confronts climate change“. And Bangladeshis will again play a leading role in the annual climate change negotiations, this year in Marrakech from 7th-18th November.

change and to press industrialised countries to curb greenhouse gas emissions. We tell this story in our new book “Bangladesh confronts climate change“. And Bangladeshis will again play a leading role in the annual climate change negotiations, this year in Marrakech from 7th-18th November.

One quarter of the population lives in the coastal southwest, which is less than 3 metres above sea level, most at risk to floods and cyclones, and most vulnerable to climate change. Soon after independence, donors pushed a disastrous scheme to build 6,000 km of dykes and embankments to create Dutch style polders. They failed to realise the heavy monsoon rains would flood the polders behind the embankments. More than 130,000 ha are so waterlogged that crops cannot be grown. Tens of thousands of farmers abandoned their land and moved to the cities. But some communities began to cut holes in the dykes to allow the polders to alternately drain and flood, adopting and updating a 18th century system that used the natural actions of the delta.

The delta has been built up because for millennia more than one billion tons of sediment flows down each year in the rivers from the Himalayas. During the monsoon, huge water volumes in the rivers and natural flooding of the land prevent tidal intrusion and push the sediment out to sea in the Bay of Bengal. But in the dry season, tidal water reaches hundreds of kilometres into the country, bringing some of the sediment back. As each high tide covers the low lying land, sediment is dropped on the land, naturally raising the level.

Recent studies have shown that the sediment naturally compacts, lowering the land level. Other research has confirmed that sea level is rising. But studies also show that in protected coastal areas without embankments, that low lying land which was just above sea level 300 years ago still is, because natural processes slowly raise the level of the land.

But the interaction of tides and monsoon has an unusual effect in the southwest, where there are two different kinds of floods at two different times of year. In the monsoon, rainfall floods the land and allows rice to be planted. Then in the dry season high tides pass over this land and drop sediment.

The Mughal rulers in the 18th century developed a system to use both floods effectively. What were called “eight  month embankments” were constructed during the monsoon, trapping rain to grow rice in flooded fields and keeping out any salt water. After the harvest, the dykes were then cut to allow any remaining rainwater to drain to prevent waterlogging, and to allow tidal seawater and sediment flooding in the dry season. The seawater is saline but the next monsoon rains wash out the salt, allowing a rice crop.

month embankments” were constructed during the monsoon, trapping rain to grow rice in flooded fields and keeping out any salt water. After the harvest, the dykes were then cut to allow any remaining rainwater to drain to prevent waterlogging, and to allow tidal seawater and sediment flooding in the dry season. The seawater is saline but the next monsoon rains wash out the salt, allowing a rice crop.

This system partially continued into the 20th century and there was a local understanding of the flood patterns – and of the way aid-funded dykes ignored this pattern. Two decades ago, communities began cutting the dykes, leading to bitter fights with government and the police. At Beel Dakatia the whole community turned out, not just with spades and buckets but with drums, pipes and other musical instruments. Cutting the dykes raised the land level inside the polders by one metre or more over three years, ending the waterlogging. The success in raising land levels and ending waterlogging won over first local councillors and then the government’s respected Centre for Environmental and Geographic Information Services (CEGIS), which also does much of the modelling for climate change planning. CEGIS and communities developed what is now called Tidal River Management (TRM) in which polders are opened one at a time for three years and allowed to flood in the dry season, raising the land level. This will need to be done every 30 years, but can keep up with climate change induced sea level rise, and has been adopted as government policy.

It is not a story known in industrialised countries, because it was done by Bangladeshis and not foreign consultants (who always seem to assume Bangladesh’s coast and rivers can be tamed in the same way as those in Europe or the United States). But Bangladesh will need help from the industrialised countries. First they need climate change to be curbed, because TRM can cope with some sea level rise but not the massive rise that will be caused by unchecked greenhouse gas emissions. Second, Bangladesh is still a very poor country and the farmers and landless workers who lose some income during the three years of TRM floodings must be compensated. The Bangladesh government budget already pays three quarters of all its spending on climate change, with only one quarter coming from donors and lenders – must Bangladesh pay to raise the land in response to the sea level rise caused by the industrialised countries?

Bangladesh confronts climate change: Keeping our heads above water is being launched on

Wednesday, 16 November, 18.00 – 20.00, London School of Economics, NAB 2.06 (New Academic Building) and on Thursday 7 December, 17.00-18.30, Theatre B, Roscoe Building, University of Manchester

November 6, 2016

Links I Liked

Waiting for stuff is such a pain isn’t it? From the Boston Globe

Irresistible listicle, especially the nuclear powered vacuum cleaners: 10 predictions for the future that got it wildly wrong

Smoking kills more people in low- and middle-income countries than TB, malaria and AIDS combined. Taxing tobacco is the obvious and best solution, so why doesn’t it happen?

COP22 will be the nerdy friend to its glamorous Parisian predecessor’. Useful curtain raiser for this week’s big climate change talks in Marrakech

China is often more popular with African publics than the US or former colonial powers. New Afrobarometer survey

China is often more popular with African publics than the US or former colonial powers. New Afrobarometer survey

Some inequality number crunching. The upward march of the top 1% (but at very different speeds in different countries). And the world’s most equal country (by income Gini) is the Ukraine, followed by Slovenia. Who knew?

Simple, disturbing, and a total downer if you happen to be male. This short film turns the tables on gender roles with devastating effect [h/t Maria Popova]

November 3, 2016

Why systems thinking changes everything for activists and reformers

This week, the Guardian ran a very nicely edited ‘long read’ extract from How Change Happens covering some of  the book’s central arguments, under the title Radical Thinking Reveals the Secrets of Making Change Happen. Here it is:

the book’s central arguments, under the title Radical Thinking Reveals the Secrets of Making Change Happen. Here it is:

Political and economic earthquakes are often sudden and unforeseeable, despite the false pundits who pop up later to claim they predicted them all along – take the fall of the Berlin Wall, the 2008 global financial crisis, or the Arab Spring (and ensuing winter). Even at a personal level, change is largely unpredictable: how many of us can say our lives have gone according to the plans we had as 16-year-olds?

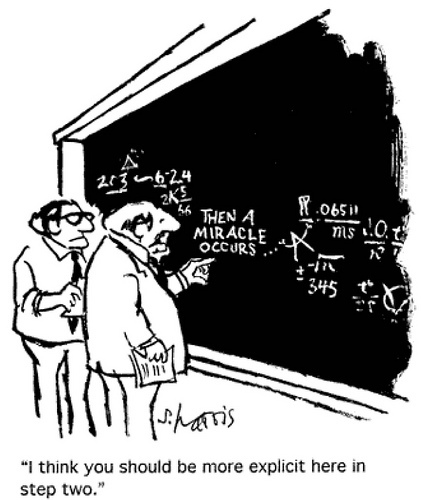

The essential mystery of the future poses a huge challenge to activists. If change is only explicable in the rear-view mirror, how can we accurately envision the future changes we seek, let alone achieve them? How can we be sure our proposals will make things better, and not fall victim to unintended consequences? People employ many concepts to grapple with such questions. I find “systems” and “complexity” two of the most helpful.

A “system” is an interconnected set of elements coherently organised in a way that achieves something. It is more than the sum of its parts: a body is more than an aggregate of individual cells; a university is not merely an agglomeration of individual students, professors, and buildings; an ecosystem is not just a set of individual plants and animals.

A defining property of human systems is complexity: because of the sheer number of relationships and feedback loops among their many elements, they cannot be reduced to simple chains of cause and effect. Think of a crowd on a city street, or a flock of starlings wheeling in the sky at dusk. Even with supercomputers, it is impossible to predict the movement of any given person or starling, but there is order; amazingly few collisions occur even on the most crowded streets.

In complex systems, change results from the interplay of many diverse and apparently unrelated factors. Those of us engaged in seeking change need to identify which elements are important and understand how they interact.

East and West German citizens climb the Berlin Wall at the Brandenburg gate on 9 November 1989. Photograph: Reuters

My interest in systems thinking began when collecting stories for my book From Poverty to Power. The light-bulb moment came on a visit to India’s Bundelkhand region, where the poor fishing communities of Tikamgarh had won rights to more than 150 large ponds. In that struggle numerous factors interacted to create change. First, a technological shift triggered changes in behaviour: the introduction of new varieties of fish, which made the ponds more profitable, induced landlords to seize ponds that had been communal. Conflict then built pressure for government action: a group of 12 brave young fishers in one village fought back, prompting a series of violent clashes that radicalized and inspired other communities; women’s groups were organized for the first time, taking control of nine ponds. Enlightened politicians and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) helped pass new laws and the police amazed everyone by enforcing them.

The fishing communities were the real heroes of the story. They tenaciously faced down a violent campaign of intimidation, moved from direct action to advocacy, and ended up winning not only access to the ponds but a series of legal and policy changes that benefited all fishing families.

The neat narrative sequence of cause and effect I’ve just written, of course, is only possible in hindsight. In the thick of the action, no-one could have said why the various actors acted as they did, or what transformed the relative

power of each. Tikamgarh’s experience highlights how unpredictable is the interaction between structures (such as state institutions), agency (by communities and individuals), and the broader context (characterized by shifts in technology, environment, demography, or norms).

Unfortunately, the way we commonly think about change projects onto the future the neat narratives we draw from  the past. Many of the mental models we use are linear plans – “if A, then B” – with profound consequences in terms of failure, frustration, and missed opportunities. As Mike Tyson memorably said, “Everyone has a plan ’til they get punched in the mouth”.

the past. Many of the mental models we use are linear plans – “if A, then B” – with profound consequences in terms of failure, frustration, and missed opportunities. As Mike Tyson memorably said, “Everyone has a plan ’til they get punched in the mouth”.

Let me illustrate with a metaphor. Baking a cake is a linear “simple” system. All I need do is find a recipe, buy the ingredients, make sure the oven is working, mix, bake, et voila! Some cakes are better than others (mine wouldn’t win any prizes), but the basic approach is fixed, replicable, and reasonably reliable. However bad your cake, you’ll probably be able to eat it.

The trouble is that real life rarely bakes like a cake. Engaging a complex system is more like raising a child. What fate would await your new baby if you decided to go linear and design a project plan setting out activities, assumptions, outputs, and outcomes for the next twenty years and then blindly followed it? Nothing good, probably.

Instead, parents make it up as they go along. And so they should. Raising a child is iterative, an endless testing of

assumptions about right and wrong, a constant adaptation to the evolving nature of the child and his or her relationship with their parents and others. Despite all the “best practice” guides preying on the insecurity of new parents, child-rearing is devoid of any “right way” of doing things. What really helps parents is experience (the second kid is usually easier), and the advice and reassurance of people who’ve been through it themselves – “mentoring” in management speak. Working in complex systems requires the same kind of iterative, collaborative, and flexible approach. Deng Xiaoping’s recipe for China’s take off epitomises this approach: “We will cross the river by feeling the stones under our feet, one by one”.

Systems are in a state of constant change. Jean Boulton, one of the authors of Embracing Complexity, likes to use the metaphor of the forest, which typically goes through cycles of growth, collapse, regeneration, and new growth. In the early part of the cycle’s growth phase, the number of species and of individual plants and animals increases quickly, as organisms arrive to exploit all available ecological niches. The forest’s components become more linked to one another, enhancing the ecosystem’s “connectedness” and multiplying the ways the forest regulates itself and maintains its stability. However, the forest’s very connectedness and efficiency eventually reduce its capacity to cope with severe outside shocks, paving the way for a collapse and eventual regeneration. Jean argues that activists need to adapt their analysis and strategy according to the stage that their political surroundings most closely resemble: growth, maturity, locked-in but fragile, or collapsing.

I was not a quick or easy convert to systems thinking, despite the fact that my neural pathways were shaped by my undergraduate degree in physics, where linear Newtonian mechanics quickly gave way to the more mind-bending world of quantum mechanics, wave particle duality, relativity, and Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle. Similarly, my experience of activism has obliged me to question linear approaches to campaigning, for example, as I hesitantly embraced the realisation that change doesn’t happen like that.

Once I began thinking about systems, I started to see complexity and unpredictable “emergent change” everywhere – in politics, economics, at work, and even in the lives of those around me.

Crises as critical junctures

Arab Spring

Change in complex systems occurs in slow, steady processes such as demographic shifts and in sudden, unforeseeable jumps. Nothing seems to change until suddenly it does, a stop–start rhythm that can confound activists. When British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan was asked what he most feared in politics, he reportedly replied in his wonderfully patrician style, “Events, dear boy”. Such “events” that disrupt social, political, or economic relations are not just a prime ministerial headache. They can open the door to previously unthinkable reforms.

Such “critical junctures”, as the economists Daron Acemoglu and James A Robinson call them, force political leaders to question their long-held assumptions about what constitutes “sound” policies, and make them more willing to take the risks associated with innovation, as the status quo suddenly appears less worth defending.

Much of the institutional framework we take for granted today was born of the trauma of the Great Depression and the second world war. The disastrous failures of policy that led to these twin catastrophes profoundly affected the thinking of political and economic leaders across the world, triggering a vastly expanded role for government in managing the economy and addressing social ills, as well as precipitating the decolonisation of large parts of the globe.

Similarly, in the 1970s the sharp rise in oil prices (and consequent economic stagnation and runaway inflation) marked the end of the post-war “Golden Age” and gave rise to a turn away from government regulation and to the idealisation of the “free market”. In communist systems, at different moments, political and economic upheaval paved the way for radical economic shifts in China and Vietnam.

Milton Friedman, the father of monetarist economics, wrote: “Only a crisis – actual or perceived – produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around. That, I believe, is our basic function: to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes politically inevitable.”

Naomi Klein, in her 2007 book The Shock Doctrine, argues that the right has used shocks much better than the left, especially in recent decades. Klein cites the example of how proponents of private education in the US managed to turn Hurricane Katrina to their advantage: “Within 19 months, New Orleans’ public school system had been almost completely replaced by privately-run charter schools.” According to the American Enterprise Institute, “Katrina accomplished in a day what Louisiana school reformers couldn’t do after years of trying.”

NGOs are not always so nimble in spotting and seizing such opportunities. Three months into the 2011 Egyptian revolution, I attended a meeting of Oxfam International’s chief executive officers (CEOs), at which they spent hours debating whether the uprising in Tahrir Square was likely to lead to a humanitarian crisis. Only then did the penny drop that the protests, upheaval, and overthrow of an oppressive regime were also a huge potential opportunity, at which point the assembled bosses showed admirable speed in allocating budgets for supporting civil society activists in Egypt, and backing it up with advocacy at the Arab League and elsewhere. But by then valuable time had passed; soon the optimism of revolution gave way to the violence and misery of repression.

Some progressive activists engaged in policy advocacy are better attuned to Friedman’s lesson. Within weeks of the appalling Rana Plaza factory collapse in Bangladesh that killed more than 1,100 people in April 2013 an international “Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh” was signed and delivered. A five-year legally binding agreement between global companies, retailers, and trade unions, the accord mandates some astounding breakthroughs: an independent inspection programme supported by the brand-name companies and involving workers and trade unions; the public disclosure of all factories, inspection reports, and corrective action plans; a commitment by signatory brands to fund improvements and maintain sourcing relationships; democratically elected health and safety committees in all factories; and worker empowerment through an extensive training programme, complaints mechanism, and the right to refuse unsafe work.

In hindsight, we can point to several factors to explain how this grisly “shock as opportunity” drove rapid movement toward better regulation:

A forum on labour rights in Bangladesh (the Ethical Trading Initiative) had already built a high degree of trust

In 2013 more than 1,100 workers were killed when the Rana Plaza building in Bangladesh collapsed. Photograph: Andrew Biraj/Reuters

between traditional antagonists (companies, unions, and NGOs). Trust allowed people to get on the phone to each other right away.

Prior work, underway since 2011, had sketched the outline of a potential accord; the Rana Plaza disaster massively escalated the pressure to act on it.

A nascent national process (the National Action Plan for Fire Safety) gave outsiders something to support and build on.

Energetic leadership from two new international trade unions (IndustriALL and UNI Global Union) helped get the right people in the room. Perhaps we should add to Friedman’s instruction “to keep alternatives alive and available”: progressive activists also need to build trust and connections among the key individuals who could implement the desired change. I am not suggesting that activists become ambulance chasers, jumping on every crisis to make their point. Rather, we must understand the windows of opportunity provided by “events, dear boy” as critical junctures when our long-term work creating constituencies for change, transforming attitudes and norms, and so on can suddenly come to fruition.

Positive deviance

One of the most exciting alternatives to business as usual goes by the name of “positive deviance”.

In December 1991, Jerry and Monique Sternin arrived in Vietnam to work for Save the Children in four communities with children aged under three, most of whom were malnourished. The Sternins asked teams of volunteers to observe in homes where children were poor but well-fed. In every case they found that the mother or father was collecting a number of tiny shrimps, crabs, or snails – making for a portion “the size of one joint of one finger” – from the rice paddies and adding these to the child’s diet.

These “positive deviant” families also instructed the home babysitter to feed the child four or even five times a day, in contrast to most families who fed young children only before parents headed to the rice fields early in the morning and in the late afternoon after returning from a working day. Results were shared on a board in the town hall, and the charts quickly became a focus of attention and buzz. By the end of the first year, 80 per cent of the children in the programme were fully rehabilitated.

In their book, The Power of Positive Deviance, the Sternins, with Richard Pascale, describe how the approach was subsequently applied in 50 countries to everything from decreasing gang violence in inner city New Jersey to reducing sex-trafficking of girls in rural Indonesia. The starting point is to “look for outliers who succeed against the odds”. But who is doing the looking also matters. If external “experts” investigate the outliers and turn the results into a toolkit, little will come of it. When communities make the discovery for themselves, behavioural change can take root – providing what the authors call “social proof”.

In their book, The Power of Positive Deviance, the Sternins, with Richard Pascale, describe how the approach was subsequently applied in 50 countries to everything from decreasing gang violence in inner city New Jersey to reducing sex-trafficking of girls in rural Indonesia. The starting point is to “look for outliers who succeed against the odds”. But who is doing the looking also matters. If external “experts” investigate the outliers and turn the results into a toolkit, little will come of it. When communities make the discovery for themselves, behavioural change can take root – providing what the authors call “social proof”.

Positive deviance capitalises on a hugely energising fact: for any given problem, someone in the community will have already identified a solution. It focuses on people’s assets and knowledge, rather than their lacks and problems. The Sternins recount their experience in Misiones Province, Argentina, where dropout rates were awful. Teachers and principals were hostile to criticism and put the blame on the parents. All that started to change when facilitators asked the “somersault question”: why were dropout rates much lower in some schools? Teachers then agreed to ask the parents at those schools, who rapidly identified teacher attitudes toward parents as the key. The positive deviant teachers were negotiating informal annual “learning contracts” with parents. When many teachers adopted that approach, dropout rates in test schools fell by 50%.

Despite its success, positive deviance remains an outlier in the aid business. The “standard model” of identifying gaps, devising initiatives to fill them, and disseminating the guidance is incredibly hard to budge. Perhaps not surprisingly, experts are often part of the problem. The Sternins write: “Those eking out existence on the margins of society grasp the simple elegance of the PD approach – in contrast to the sceptical consideration of the more educated and/or privileged. Uptake seems in inverse proportion to prosperity, formal authority, years of schooling and degrees hanging on walls.”

I can vouch from personal experience how hard it is to give up my learned role and become a facilitator. Holding back from providing your own answer when you ask a group a question is, as the Sternins put it, “more difficult than trying to stifle an oncoming sneeze”.

Thinking in systems should change everything

In the first film in the Matrix series (the only one worth watching), the hero, Neo, suddenly starts to see the matrix of ones and zeroes that lies beneath the surface of his world, at which point he becomes invincible. I have the same feeling about systems (aside from the invincibility part). Thinking in systems should change everything, including the way we look at politics, economics, society, and even ourselves, in new and exciting ways.

It also poses a devastating challenge to traditional linear planning approaches and to our ways of working. We activists need to become better “reflectivists”, taking the time to understand the system before (and while) engaging with it. We need to better understand the stop–start rhythm of change exhibited by complex systems and adapt our efforts accordingly. And we need to become less arrogant, more willing to learn from accidents, from failures, and from other people. Finally, we have to make friends with ambiguity and uncertainty, while maintaining the energy and determination so essential to changing the world.

It isn’t easy, but it is entirely possible, as I hope I have shown. Once we learn to “dance with the system”, no other partner will do.

Is Good Advocacy a Science or an Art (or just luck), and how can we sharpen it?

Helen Tilley ( h.tilley@odi.org )

Hannah Caddick

Josephine Tsui

Helen Tilley

, is a Research Fellow, Josephine Tsui ( j.tsui@odi.org ) a Research Officer, and Hannah Caddick ( h.caddick@odi.org ) a Communications Officer, in the Research and Policy in Development Programme at the Overseas Development Institute.

‘There is an art to science, and a science in art; the two are not enemies, but different aspects of the whole.’ — Issac Asimov

In a recent blog, Duncan wrote about the professionalization of advocacy with the proliferation of tools and toolkits, and about the delicate balancing act between the art and science of advocacy. He expressed a degree of concern: that if we ‘projectise’ and create tools, we get away from advocacy’s heart – away from smart, entrepreneurial thinking.

A team in the Research and Policy in Development Programme (RAPID) at the Overseas Development Institute has been working on just this: creating an advocacy tool, for a project mentioned in the blog. Much of what he said rang bells with us. It’s true that advocacy practitioners need the freedom to pursue change pathways they believe will work. Change happens because of a myriad of external factors, including ‘technological and demographic change, long-term shifts in attitudes and beliefs, the rise and fall of sectors…big shocks and events…’, so flexibility is crucial.

But policy change can also be down to more than just luck; in the words commonly attributed to Seneca, ‘Luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity’. We know that some advocates are better informed and better  prepared for change than others. Tools can help us to be systematically informed and prepared by guiding how we monitor our work, and reminding us to pay attention to what we are doing.

prepared for change than others. Tools can help us to be systematically informed and prepared by guiding how we monitor our work, and reminding us to pay attention to what we are doing.

As Issac Asimov reminds us, art and science work together. It’s not always which systems we use, but how we use them. In RAPID, we suggest users think of our tools like a compass rather than a map. In advocacy, a compass helps to guide practitioners through challenges and towards success; other, more rigid tools can be too prescriptive.

Our team has been working collaboratively with Save the Children to develop a tool for their offices around the world, to help them understand their contribution to change in political will (not Duncan’s favourite term, we realise).

The project has taken us along a winding path where we have had to find ways to deal with various challenges, including how to capture those things that many advocates consider just day-to-day conversations to get your work done.

The initial tool we’ve developed for people to test applies outcome mapping principles and takes the user through a step-by-step process to record what they are doing to influence political will. Despite the ambitious aims, we tried to devise something simple to capture things that are often not recorded (watch this space, we will be publishing soon!).

In doing so, there are two areas of innovation that have required a combination of science and art.

Measuring the unmeasurable. Political will has been called ‘the slipperiest concept in the policy lexicon’ (Hammergren, 1998: 12) and it is true that typically ‘we spend more time lamenting its absence than analysing what it means’ (Evans, 2001: 8). At the same time to say ‘“it all depends on political will” – is a simplistic escape clause’ (Jones, Jones, Shaxson and Walker, 2012: 8).

There have been many commendable efforts to pin down political will (including practical models in participatory governance and as a tool for articulating an advocacy theory of change). We disaggregated political will into simple categories, identifiable by behaviour changes in the target stakeholders, adapting Brinkerhoff’s Unpacking the concept of political will to confront corruption.

Using progress markers, we ask Save the Children users to break down into smaller steps the behaviour changes they might see if the subject of their advocacy work were to understand, support or engage with their advocacy objective. Users then categorise these by the type of change in political will observed. The aim is to help advocates think about how changes are occurring.

Applying adaptive management, an iterative way of working through problems and tasks, monitoring as you go so that you can respond and adapt: ‘Much development work fails because, having identified a problem, it does not have a method to generate a viable solution.’ While the policy objective will have been decided, how to achieve it has not. By managing their project adaptively, users can change their approach and tactics to more effectively work towards policy change.

A toolkit

Reflection, including upon context and other influences upon change, is the most important step in the tool. If the advocacy environment in, say, Ethiopia is very restricted, how can you adapt your tactics? What’s working and what’s not working? Advocacy entrepreneurs may do this without thinking. But the tool provides space for this reflection when it might otherwise be neglected or forgotten, or lost with changes in personnel.

Tools are only good as the data input into them, and if they usefully serve the users. The political will tool we have developed with Save the Children uses perception-based information and so being aware of and acknowledging biases is critical. It is also important to use participatory approaches to ‘ensure data is bottom-up and relevant to people on the ground’ by bringing in people with different perspectives to question and challenge. Yes, this can be burdensome but it can also be done in a manageable way.

While the tool builds a halfway house between the art and science to provide useful information, the way in which it is used – the entrepreneurship of the user – is at its core. This also requires flexibility and understanding from donors: encouraging reporting on things that might not be going so well without the risk of it affecting funding. After all, this is often where the real lessons can be learnt.

November 2, 2016

Why aren’t ‘Diaries of the Poor’ a standard research tool?

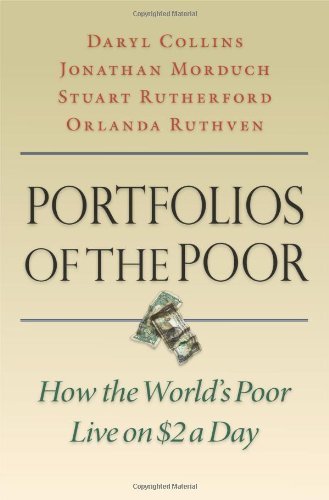

I’ve been having lots of buzzy conversations about diaries recently. Not my own (haven’t done that since I was a  teenager), but diaries as a research method. The initial idea came from one of my all-time favourite bits of bottom-up research, the book Portfolios of the Poor. Here are the relevant paras from my review:

teenager), but diaries as a research method. The initial idea came from one of my all-time favourite bits of bottom-up research, the book Portfolios of the Poor. Here are the relevant paras from my review:

‘A financial fly-on-the-wall account of how poor people manage money. To find out, the researchers set up ‘financial diaries’ with 250 households in selected communities in 3 countries (Bangladesh, India and South Africa). For a year, researchers visited every fortnight and picked over people’s financial affairs. The book then assimilates the findings, and intersperses them with unmistakably real-life examples from among the 250 households (‘Pumza is a sheep intestine seller living in the crowded urban hostels of Cape Town……’)

The first and perhaps most striking finding is the sheer complexity, scale and variety of poor people’s financial activity. People living in poverty need financial skills more than the better off. Just to get by from day to day, they borrow, save, and exchange cash with a huge variety of friends, family, neighbours and institutions, both formal and informal. These last include savings clubs, savings-and-loan clubs, insurance clubs, microfinance institutions, and banks. ‘At any one time, the average poor household has a fistful of financial relationships on the go.’ Every one of the 250 households had both savings and debt of some sort, and no household used fewer than four types of financial instrument over the course of the year. Rural households have turnovers (i.e. total cash flows in or out) between 10  and 30 times greater than their asset value at the end of the year.’

and 30 times greater than their asset value at the end of the year.’

That was 2009, and the book’s been at the back of my mind ever since, but has recently come up when discussing entirely different issues. Why not use the same approach – deep, fine-grained observation of how poor people actually lead their lives, with researchers building up relationships of trust through repeated visits and conversations – on, say, how poor people access justice, or experience the state, or the environment? Or how they understand health and deal with people getting sick?

The new research consortium on empowerment and accountability in fragile and conflict settings has picked this up, so it looks like we can run some pilots to develop a methodology – v exciting.

To do it, you need sharp, respectful researchers able to go back to the same households repeatedly over a year or two. Aka students – a Masters student could easily use this as a topic for a dissertation, and receive a stipend that would help them through college. So the approach would lend itself to a partnership with a local university, which can find, say, 10 students who take on 10 families each.

But it could also go further than Portfolios of the Poor in terms of agency. Rather than the researcher coming for their fortnightly download over a cup of tea, the family itself could be asked to record their impressions and experiences – perhaps with a video diary on a phone or flip cam, and then the researcher could come and triangulate that material with their own conversation.

My colleague Irene Guijt was unconvinced by this (and coined the wonderful acronym IIMBSD – If I May Be So Dutch in her reply). What’s the benefit of all this research she asked, either for improving the actions of outsiders or to the people themselves? Provisional answers:

For aid agencies and governments: Portfolios of the Poor was designed to identify where poor people already had all

Diary of a Victorian Child Worker

the financial products they needed, and where new market-based mechanisms might help (it turned out people were fine on short-term savings, but had a gap on long-term provision on things like pensions). The governance equivalent would be to identify what institutions (formal and informal) actually matter to poor families – a pretty good starting point for thinking who to partner with, for example.

Poor people would benefit because the research, especially if it focuses on agency, can be empowering in itself – being listened to respectfully, the act of recording and analysing your own interactions with authority. The chair of the research consortium, John Gaventa, made his name doing exactly this kind of thing in the Appalachians in the 1970s – working with poor families to research who owned their land, with transformative impacts on social organization. Looks like we may be coming full circle.

So I’ll end with the usual questions – what am I missing? Where has it happened already? What do you think?

November 1, 2016

10 Frontier Technologies for International Development

Ben Ramalingam

, leader of the Digital and Technology research group at the Institute of Development Studies  (IDS), introduces their new report on new and emerging technologies, and how international organisations can capitalise on their potential.

(IDS), introduces their new report on new and emerging technologies, and how international organisations can capitalise on their potential.

New and emerging technologies have often underpinned and enabled significant development progress over the decades – from vaccines to mobile phones to the internet. The UN has recently called for much more work in this area, arguing that it is ‘critical to assess how technology can be mobilized to provide solutions to our greatest challenges’ in achieving the Global Goals. If by 2030 we are to extend universal healthcare to nine billion people, provide them with sustainable sources of food and energy, and develop secure and inclusive work – to pick just four of the goals – it is clear that business as usual and reliance on existing solutions won’t get us there.

But development and technology have had at best an uneven history. There are well-known and justified critiques based on technological over-optimism and ‘technology transfer’ that consists of little more than development organisations trying to ‘copy and paste’ new high-tech innovations into developing countries with little attention to context or complexity. There are also numerous instances where the technological development has happened despite the development sector and it has been left sprinting to catch up.

The perils of technology transfer from

Aid on the Edge of Chaos

The perils of technology transfer from

Aid on the Edge of Chaos

We still see these issues today – as Duncan has argued elsewhere on this blog, it seems ‘the cycle is endlessly repeated: a new magic bullet, rapidly turned into a straw man… then someone takes a cold hard look at the evidence and concludes that it’s all about the institutions, governance etc.’ The technology hype cycle is not just damaging for development prospects and ambitions, but also ignores the real lessons of successful technological innovations from the past six decades.

Put simply: the more grounded technological development efforts are in specific, tangible development and

The Ten Frontier Technologies report

humanitarian challenges, the more sensitive they are to national and local political and cultural contexts, and the more they include local communities, organizations and governments as active creators and owners and not just as targets or end-users, the more likely they are to be successful.

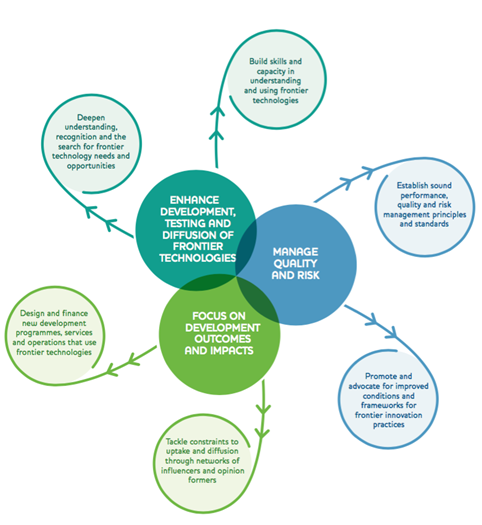

This is one of the overarching messages from the new report Ten Frontier Technologies for International Development by the IDS Digital and Technology research group, supported by, and being launched today at, DFID. We explore ten technologies (see figure below) across five areas and set out a range of ideas for how development organisations could capitalise on the opportunity of technology without falling prey to techno-optimism or, worse, techno-babble.

The Ten Technologies Across Five Categories

The Ten Technologies Across Five Categories

Examples include:

Transforming access to energy . New partnerships between private sector innovators and development organisations have kick-started new markets in solar lighting, with remote digitally-enabled monitoring, control and payment systems – the “internet of things” – being key to the sector’s breakthrough. Increasingly widespread across East Africa and Asia, mobile-enabled solar power has provided millions of people with affordable, sustainable, energy, while new battery technologies can be expected to further extend impacts.

Collaborative use of essential assets . Just as AirBnB and Uber have disrupted existing industries through a combination of new technology, privately owned assets, lower prices, and greater consumer choice, there are a range of initiatives across developing countries that are doing the same with the assets needed by poor and marginalised communities. From bicycles in China, to motorbikes in Indonesia, to tractors in Nigeria, expensive assets are becoming more affordable to those who would otherwise not have access.

Overcoming infrastructure bottlenecks for remote areas . While the use of drones for digital mapping is well-established, they are increasingly being used for transportation and logistics, enabling delivery of urgently needed supplies, such as medicine or blood, to inaccessible places, thereby overcoming logistical and transportation problems. In Africa in particular, governments have taken the lead in establishing necessary infrastructure and legislation. Notably, earlier this year Rwanda launched one of the first national-scale pilots of drones for healthcare delivery.

In order to capitalise on these and other exciting developments, we need to put in place a new kind of innovation system: more evidence-based and systematic, more anticipatory and dynamic, more open to new ideas and approaches, wherever and from whomever they originate and ultimately more geared to the needs and opportunities faced by poor and vulnerable people.

With this in mind, we have three sets of recommendations for the international development community:

enhancing the development, testing and diffusion of frontier technologies;

better management of quality and risk throughout the frontier technology development process;

and focusing efforts on achieving outcomes and impacts, working in adaptive and politically intelligent ways (see infographic below for more details).

These recommendations underpin a new Frontier Technology Livestreaming initiative within DFID to catalyse new ideas and approaches across its global portfolio, being launched today alongside the report.

The inevitable infographic on recommendations

I’d like to give the final word to Sir Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the World Wide Web, from his foreword to the report:

“Without due care and attention, these new technologies will become uneven playing fields, with a select few winners and many more losers… to ensure these exciting technologies realise their potential to contribute to economic growth and social progress, people in developing countries will need sustained and thoughtful engagement. Along with patient investment in novel approaches, there will need to be adaptive and intelligent approaches to anticipate and head off risks and protect users’ rights, as well as creative ideas for building these technologies on open standards and applying them in ways that meet the needs of those in developing countries. I urge all leaders – be they politicians, development policymakers, or technologists and innovators – to heed this timely call, and to come together to realise the greater promise of open and inclusive technology in creating a more sustainable and fairer world for future generations.”

October 30, 2016

Links I Liked

Closed, repressed, obstructed, narrowed or open? Tracking civil society space. New interactive tool from CIVICUS,  including country ratings and a searchable database

including country ratings and a searchable database

Michael Spence argues that by rebalancing power relationships in the world’s democracies, digital technology is partly responsible for the increased focus on inequality

Seven useful tips for new development masters students, especially on not obsessing about your grades

Brilliant and thought provoking. If women wrote men the way men write women… [h/t Tim Harford]

When the outlook is bad, the World Bank reaches for political explanations; when it’s good, it’s all down to economic policy. Naomi Hossain on Bangladesh and the Bank

The 74 articles in the 2016 World Social Science Report on inequality now have separate links, including to my 4 pager on the history of redistribution

16 mind numbing, gnaw-your-own-arms-off pieces of office jargon – and suggested alternatives, eg “When all the rhubarb is harvested.” (for ‘at the end of the day’)

Sorry, you’ll have to put up with some book-related links for the next few weeks. I’m doing a Twitter chat on Thursday lunchtime. Talks at Sheffield, LSE, Edinburgh and DFID this week. Then off to Geneva to speak at UNRISD on 7th November. Then Netherlands 9-11th (details to follow). Other Geneva/Dutch organizations/individuals please let me know if you want to set something up.

Sorry, you’ll have to put up with some book-related links for the next few weeks. I’m doing a Twitter chat on Thursday lunchtime. Talks at Sheffield, LSE, Edinburgh and DFID this week. Then off to Geneva to speak at UNRISD on 7th November. Then Netherlands 9-11th (details to follow). Other Geneva/Dutch organizations/individuals please let me know if you want to set something up.

Nice reviews from Diana Coyle and Jamie Pett, the best four word review ever  from Dani Rodrik, and a nice piss-take from Steve Lewis

from Dani Rodrik, and a nice piss-take from Steve Lewis

October 27, 2016

Big new research programme on empowerment and accountability in fragile settings gets under way – can you help choose its name?

Whatever happened to resting on your laurels? The book’s just published, and I’m onto the next thing – a five year

Pakistan

research consortium on empowerment and accountability in fragile and conflict settings (FCS). Spent 3 days recently with some sharp minds from an alphabet soup of project partners – IDS, ITAD, IDEAS, CSSR, PASGR and ARC, wading through a stack of initial analyses, including my draft paper on theories of change.

You’ll be hearing a lot about this project (my recent trip to Myanmar was also part of it). First job is to pick a good name – cue FP2P wisdom of crowds. Here are the top 3 candidates (you should have seen the other ones….):

Note: There is a poll embedded within this post, please visit the site to participate in this post's poll.

Over to you – please vote, and if you want to explain your choice (or suggest a better alternative), the comments section is always open.

Over to you – please vote, and if you want to explain your choice (or suggest a better alternative), the comments section is always open.

Some of the interesting stuff from the discussion:

Shrinking space is not only about CSOs – traditional Western aid donors are also finding their room for manoeuvre shrinking. More competition from the likes of China and the Gulf States, with a very different/no interest in empowerment and accountability; rising anti-Western sentiment in countries such as Egypt. Should outsiders pull back from direct relationships with local organizations, for fear of damaging them by association? Focus on tech solutions and the ‘enabling environment’ as the World Bank’s Shanta Devarajan argues? And when should they just simply stay well away and let domestic processes play out?

We must stop equating civil society with formal CSOs: a lot of criticism of the aid business ‘NGO-ising’ hitherto accountable popular movements, and turning them into formal aid-hungry mini-me’s. Time to stand back, look much more broadly at the expressions of popular organization, many of them informal (funeral societies, sports clubs, cultural associations), and whether there is any role for outsiders in supporting them?

Violence is really hard to keep in focus. Conflict generally, and physical violence in particular, are a prominent feature of FCS – a spectrum from domestic violence to civil war. But it seems to be really hard for aid types to really engage with ‘the dark side’ – most of us are instinctively averse to violence, so we either talk about people being victims of it, and how it can be stopped (peace-building etc), or we keep forgetting about it in our desire to get back to empowerment and accountability and lots of basically peacetime activity. Typically people may start by talking about ‘violence’, but that rapidly becomes ‘conflict’, which is then reduced to peaceful protest – voila! Airbrushing completed; discomfiture avoided. But what about violence as a positive force for empowerment and accountability (‘the government only listens to us when we burn things down’) and what, if anything, can be done when violence is part of the ‘disabling environment’ but people still have to get on with their lives. Essay question: discuss

Nigeria

empowerment and accountability under Boko Haram.

What’s the link with the economy? Do we buy the ‘economic growth → middle class → political demands for accountability and good governance’ argument? When does economic empowerment lead to social and political progress and vice versa? Where does power fit in?

Working with the Grain is all very well, but what about when the grain sucks (e.g. on women’s rights)? Danger is that a Machiavellian fascination with hybrid institutions and political settlements leads external actors to abandon basic human rights and norms.

And some personal hobbyhorses that made me very happy when they got through to the all-important short list for the next batch of research papers:

Role of faith and religion (not the same thing). Especially in FCS, where formal institutions are often weak or absent, informal ones are relatively more prominent. That includes faith groups, which is where values are shaped, and often services provided. Their impact can be good or bad (secular aid types always tend to focus on the latter). The project is going to take a look at how faith and religion operate in these environments, the links to empowerment and accountability (or their opposite) and possible implications for ‘external actors’ – i.e. us.

Role of faith and religion (not the same thing). Especially in FCS, where formal institutions are often weak or absent, informal ones are relatively more prominent. That includes faith groups, which is where values are shaped, and often services provided. Their impact can be good or bad (secular aid types always tend to focus on the latter). The project is going to take a look at how faith and religion operate in these environments, the links to empowerment and accountability (or their opposite) and possible implications for ‘external actors’ – i.e. us.

Fear/psychology. I’ve been increasingly struck by the extent to which development thinking stops at the mind’s edge. We barely go further than vague statements about ‘power within’. But in FCS issues like fear, suspicion and mistrust are crucial determinants of (dis)empowerment and collective (in)action. Conflict leaves a legacy of trauma that cripples some and galvanizes others – why? What is the role of culture in oppression, resilience and identity?

Positive Deviance: Identifying positive outliers that have emerged within the system is especially important when conventional solutions are hard to find – FCS definitely qualify. Glad to see a lot of discussion about the importance of looking hard for positive examples of empowerment and accountability in these places, before we steam in with our toolkits and project proposals.

Governance Diaries: v excited about these, but this post is already too long – more to follow.

October 26, 2016

Can Publishers survive Open Access? We’ll find out when How Change Happens is published today

It’s Open Access Week and How Change Happens is officially published in the UK today, as both a book and an open access pdf. The process has been pretty exciting.

access pdf. The process has been pretty exciting.

The traditional author descends from the mountain of scholarship clutching a rather expensive tablet of stone, in which his/her wisdom is set out to a suitably grateful but largely passive public. Think of force-feeding geese. Appropriately for a book about change, we’re trying to do things differently this time.

The book has drawn on the ‘wisdom of crowds’ (i.e. you lot) at regular intervals throughout its production.

Choosing the publisher: Oxfam invited a range of publishers to submit proposals that included Open Access. OUP were altogether the most positive – they wanted to try out different business models, and were clearly up for it.

The writing: I’m a blogaholic with a five-posts-a-week habit, which has its advantages. The blog acted as a first draft, a way of nailing down and road-testing emerging ideas and themes and then, after a period of suitably painful authorial seclusion to turn these ideas into a semi-coherent whole, publishing and inviting comments on the first draft. Not that I find this process easy – my first reaction to comments, especially critical ones is usually along the lines of ‘I hate you – why can’t you just say it’s great as it is?!’ But when I calm down and read the comments, they are often incredibly helpful (see my Oxfam guide on how to comment on other people’s stuff). After all, this is free consultancy, right?

Some of my favourite comments came from a Pakistani humanitarian leader called Masood Ul Mulk, who emailed out of the blue. I ended up including several of them in the book, including this one, which opens the concluding chapter:

‘I will never forget a Princeton graduate who was brought in to undertake a change programme within an educational institution in a remote region. He started by throwing out ‘ inef fi cient people. ’ But he started moving those who represented the tribal balance in the region out of their jobs, the people from the mountains descended and surrounded him in his house. He was a virtual prisoner for days. I remember going to meet him and he kept shaking his head: ‘ They never taught me this at Princeton, they told me the villagers were simple people.’’

The horror, the horror…..

The cover: We were sent three potential designs from OUP, and since I was always rubbish at art at school, I suggested we throw it open for voting. People got very involved (everyone has an opinion on something like this), over 1,000 voted in two rounds, and now people see the book on the stalls and say ‘I voted for that one!’ – a marketer’s dream of identification with ‘the product’. I’m particularly glad we did it because I originally preferred one of the other designs (which I now realize was awful) but was won over by the comments and the poll.

Now for the launch, we are going into open access and social media overdrive – a funky new website with lots of background materials on the themes covered in the book, a guide to the various launch events, and of course interminable blogs and tweets trying to arm-twist potential readers into forking out (or at least downloading) a copy. Just in case I overdo things, I’m running a precautionary poll on the blog to see if people are getting sick of the hype – so far only 12% have ticked ‘bloody hell, one more mention and I’m unsubscribing’, but I’m keeping an eye on it. We’re also thinking about a MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) and other teaching packages based on the book.

So as of today, the book will be free to download, as well as in all decent bookshops in hardback and online as an ebook. OUP is watching what happens with bated breath. Adam Swallow, my jovial OUP editor, sums up how all this looks from a publisher’s point of view:

‘Will anyone buy the printed version, or the e-book via a distributor when they can download for free? Well the download may be fine if you want to read some of it on-screen, or use search functions beyond an index, but start printing some chapters yourself and it can soon add up (at 4p per page, printing out the PDF would cost you £11.52, compared to RRP of £16.99 for a crisp hardback).

How Change Happens goes beyond what publishers have traditionally done as a marketing tactic. The Creative Commons licence that it is published with allows anyone to read and share the full final publication online. The PDF version can be placed anywhere online without breaching copyright. It is also permanent; once published under the CC licence it will be free forever. This means free in multiple places online, and will outlast any commercial site, author life, or publisher. It is content that will be preserved, by being held in numerous locations, and change as people make the text available in new formats. Where social media, the marketing, the Free, more than promotes the hardcopy, it has an on-going and parallel existence. That’s not just a marketing ploy.’

Exciting stuff. As an author, I applaud OUP’s energy and innovation and hope it works for them – we’ll keep you posted.

October 25, 2016

What’s happening on Global Inequality? Putting the ‘elephant graph’ to sleep with a ‘hockey stick’

For our second post on how to measure inequality (here’s the first), Muheed Jamaldeen, Senior Economist at Oxfam Australia, discusses absolute v relative

For our second post on how to measure inequality (here’s the first), Muheed Jamaldeen, Senior Economist at Oxfam Australia, discusses absolute v relative

Back in December 2013, two economists at the World Bank – Christopher Lakner and Branko Milanovic; produced a paper on ‘Global Income Distribution’, which presented a newly compiled and improved database of national household surveys between 1988 and 2008. As part of the analysis in this paper, Lakner and Milanovic produced Growth Incidence Curves (GIC), which show percentage growth in income by global percentile.

One of these charts has come to be known as the ‘elephant graph’ – an inverted supine S shape gives rise to this name. The vertical (Y) axis shows the percentage increase in income between 1998 and 2008; the horizontal (X) axis shows income percentiles – whereabouts you are in the global distribution of income.

This analysis shows that incomes for the poorest half of the world (up to the 50th percentile) have grown as fast as income increases experienced by the top 1% of the world.

This graph has proven to be extremely popular because it has simultaneously supported the arguments of the proponents of globalisation, and those who are concerned about its impacts on the middle class in rich countries. At Oxfam, we are concerned that the graph also gives the impression that inequality is not a problem in developing countries, as their incomes have grown.

This graph has proven to be extremely popular because it has simultaneously supported the arguments of the proponents of globalisation, and those who are concerned about its impacts on the middle class in rich countries. At Oxfam, we are concerned that the graph also gives the impression that inequality is not a problem in developing countries, as their incomes have grown.

Advocates of unrestrained free-market economics also use the growth rate of developing country incomes to argue that concerns about rising inequality are overblown (let’s call them the ‘naysayers’). This implies that any corrections to inequality might adversely impact on poverty reduction.

However, there are a number of reasons why using the ‘elephant graph’ (and income growth rates) in this way is, simply put – misleading.

Comparing income growth rates across vastly different income levels is meaningless

The first, and most important of these is that for the poorest people, income growth rates matter little. For instance, a 10% increase on an income of $100 translates to a $10 increase in income. By contrast, a 10% increase for a person on $10,000 income translates to an increase of $1000. You can buy a lot more with $1000 dollars than you can with $10. In the case of the ‘elephant graph’, those between the 40th and 50th percentiles experienced 70% increase in incomes – however, this is from a starting point of around $550 in 1998.

One way to correct for this misleading visual representation is to alter the point of reference for the calculation of the percentage increase. Instead of looking at the percentage income growth rate for each percentile, we used the common reference point of average incomes in 1998. This (purple line) represents the speed at which each percentile has grown compared to the average income level (around $3300) 20 years ago.

The ‘elephant graph’ immediately disappears, and is instead replaced with a ‘hockey stick’ graph (right axis). Since each percentile now uses the same reference point of 1988 average income (or common denominator for the numerically inclined!), we can now see that over the last 20 years the vast majority of income growth (in relative percentage terms) has accrued to the top 1%, and that the growth experienced by the poorest half of the world pales in comparison. Alternative common reference points produce similar ‘hockey stick’ shaped graphs.

The ‘elephant graph’ immediately disappears, and is instead replaced with a ‘hockey stick’ graph (right axis). Since each percentile now uses the same reference point of 1988 average income (or common denominator for the numerically inclined!), we can now see that over the last 20 years the vast majority of income growth (in relative percentage terms) has accrued to the top 1%, and that the growth experienced by the poorest half of the world pales in comparison. Alternative common reference points produce similar ‘hockey stick’ shaped graphs.

Growth in income levels matter more than growth rates

In the graph below, we compare the income growth levels (right axis) with the original ‘elephant graph’ which shows percentage increases in income between 1998 and 2008 for each percentile (left axis). When both absolute level increases, and percentage increases are plotted on the same graph, it is clear that though those at the 40th and 50th percentile had a growth rate of 70%, the absolute increase in income is around $400.Though the top 1% experienced similar income growth in percentage terms, the absolute increase was over $25,000, rising from around $39,000 to over $64,000.

In other words, the top 1% experienced nearly 65 times the absolute income growth of the poorest half of the world – an astonishing fact concealed by the ‘elephant graph’. The plot of income growth levels (right axis), again, reveals a ‘hockey stick’ graph, showing that the vast majority of income growth (in levels) accrued to the richest. Early this year, Oxfam’s annual inequality report showed that nearly half (46%) of total global income growth went to the richest 10% whilst the poorest 10 saw less than 1% of total income growth.

To reduce inequality, much higher income growth rates are required for the poor

To reduce inequality, much higher income growth rates are required for the poor

Since the ‘elephant graph’ shows that the poor have experienced ‘strong’ income growth rates, it is easy to think that inequality must be decreasing.

Let’s put that claim to the test.

In the graph below (orange line), we simulate the 20 year income growth rate (between 1988 and 2008) that would have been required for the bottom percentiles (up to the 70th) to achieve the average income levels in 2008 of around $4100. (The income growth rates for percentiles above P 60-70 were unchanged from the original data.) This shows (right axis) that the poorest percentile (just to get to the average income. Instead, this group experienced around 25% growth over two decades (or 1.1% compounding annually).

At the current rate (compounding every 20 years), it would take over 250 years for the poorest 10% to get to the 2008 average. For those between the 40th and 50th percentiles, it would take 55 years. Similarly for P 50-60, it would take 41 years, and for P 60-70 it would take 29 years at current income growth rates compounding every 20 years.

Again, these facts are simply not apparent from the ‘elephant graph’.

Again, these facts are simply not apparent from the ‘elephant graph’.

To be fair to Lakner and Milanovic, as shown below, they do note some of these limitations in their 2013 paper (see p.30).

“While the global GIC showed relatively large gains for the portion of the distribution around the median, we need to recall that these gains were measured in relative (percentage) terms. But precisely because global income inequality is extremely high, and incomes at the top are several orders of magnitude greater than incomes at the median … the absolute gains are much greater for higher percentiles.”

But of course, the naysayers use the ‘elephant graph’ with neither a rudimentary understanding of what it is trying to show, nor its limitations. Like all graphs and visuals it serves a political purpose for those with set ideological views, which, unfortunately compromises the intellectual integrity of the Lakner and Milanovic analysis.

The ‘elephant graph’ is also wrongly being used to argue that inequality is a developed country issue, and that global inequality is declining by virtue of high income growth rates for the bottom percentiles. We have shown three reasons why the ‘elephant graph’, though not intended, masks the true extent of global inequality.

It’s time to put the ‘elephant graph’ to rest, and replace it with the ‘hockey stick’ graph once and for all.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers