Duncan Green's Blog, page 135

September 12, 2016

How do you do ‘Adaptive Programming’? Two examples of Practical Experience help with some of the answers

Helen Derbyshire (left) of SAVI and on what all the fuss is about.

At a glance the two DFID programmes we work on are very different. SAVI (and its successor programme ECP) is a large scale, long-term initiative which focuses on citizens’ engagement in governance in Nigeria. LASER is a modest, shorter-term investment climate reform programme operating in eight countries. But, despite our differences, learning by doing and working in an adaptive manner are central to how we both work and we’ve been sharing approaches and lessons between ourselves for some time.

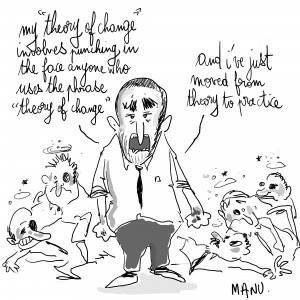

Recently we’ve experienced a spike in interest from others in our experience of adaptive programming. Programme staff, donor representatives and suppliers are asking us what it is that we actually do to deliver programmes that aim to react to learning, changes in context and evolving partner needs. Our responses have often been met with either noticeable scepticism that adaptive programming is just the latest development fad, or, alternatively, the rhetorical question “but isn’t that what we have always done?’.

Both of these reactions are of course completely reasonable. Yes, good development practitioners have always championed some of what adaptive programming is advocating – such as local partners taking ownership of and shaping activities. And yes, there is a serious risk that adaptive programming could become just the latest development buzzword.

Both of these reactions are of course completely reasonable. Yes, good development practitioners have always championed some of what adaptive programming is advocating – such as local partners taking ownership of and shaping activities. And yes, there is a serious risk that adaptive programming could become just the latest development buzzword.

But our experience is that adaptive programming involves considerable innovation and swimming against the tide of conventional practice. There are fundamental differences in how we do things that differentiate adaptive approach from more conventional approaches – and we believe this makes a significant difference to the impact we can, and have, achieved.

Town hall meeting, Enugu State, Nigeria. Photograph: George Osodi/SAVI

So what do we do differently? For us, adaptive programming has been about explicitly embedding learning in all elements and at all levels of our work, and devolving power to where strategic and delivery decisions are made. It has been about a significant change in mindset at both technical and operational levels. Technically, we are shaped by contextual analysis and processes of learning by doing. Operationally we view programme management as a function which enables and supports, rather than drives, programme delivery.

It is well documented that adaptive programming is about working in ways that put learning at the centre, and that are politically smart and locally led. Our experience is that the key challenge in achieving this is finding ways of enabling this kind of adaptation whilst at the same time meeting donor accountability requirements. All too easily the requirements of donors and their implementing organizations (‘suppliers’) dominate and drive implementation and close down the space for learning and adaptation. Meeting this challenge requires ingenuity and persistence – and is in itself a continuous exercise in problem driven iterative adaptation!

For us, some of the key lessons to date are:

Build in flexibility from the outset. Design, procurement and contracting processes need to enable the

Launch of the judiciary Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) pilot, Kenya. Photograph: LASER

programme to be adaptive from the outset. This means programme design setting the direction of the programme and its level of ambition, rather than using design as an opportunity to nail down results, resources, activities and spend. It also means having procurement processes which promote and incentivise adaptation. Donors should be looking to suppliers for evidence of adaptive approaches rather than solutions. Suppliers need to find ways of aligning commercial interests and incentives with adaptive planning, enabling flexible access to relevant skills rather than locking in inputs.

Integrate technical leadership and operations management. In a conventional programme, where plans, targets, budgets and personnel inputs are planned and agreed up front, the programme management is responsible for ensuring effective delivery – on time, within budget and according to agreed milestones. This operations management task drives the programme forward. In an adaptive programme, technical leadership in throughout the programme is critical – to champion, support and ensure the quality of adaptive work. Technical leadership is much more than sector-specific expertise. Technical leadership is needed to train, support and empower front line staff to think and work politically, learn by doing, and be adaptive. Technical leadership is also needed to shape the enabling environment within the programme for learning and adaptation can take place. Systems for monitoring, financial management, staff management, and delivering value for money all need to need to support and enable adaptive programme delivery, rather than control and drive it. To this end, technical leadership and operations management need to be integrated and mutually compatible from the start of the programme, with the former shaping the latter. Get the right people. Adaptive programming is less about technical expertise than about facilitation, team work, humility and mutual problem solving. This requires “soft skills” from staff which are generally not reflected in technical CVs (or prioritised in recruitment). From a supplier perspective this can mean significant change in the profiles of staff recruited, and from a donor perspective putting in place a procurement process that includes assessing teams for their ability to work in adaptive ways.

Get the right people. Adaptive programming is less about technical expertise than about facilitation, team work, humility and mutual problem solving. This requires “soft skills” from staff which are generally not reflected in technical CVs (or prioritised in recruitment). From a supplier perspective this can mean significant change in the profiles of staff recruited, and from a donor perspective putting in place a procurement process that includes assessing teams for their ability to work in adaptive ways.

Aim for transparency and accountability in financial management – but not necessarily complete predictability. Financial forecasting and management processes need to facilitate adaptive planning, allowing financial resources to be moved around and deployed where necessary – whilst still meeting donor requirements for predictable financial flows and value for money. Regular budget review and continuous re-forecasting are essential.

Invest in time, space, skills and systems for staff and partners to learn and adapt. Adaptive management  approaches, capacities and relationships take time to evolve and can be undermined by pressure for quick wins. Front line staff (and partners) need to be actively involved in analysing their changing context, and monitoring the effectiveness of their activities. They need to be supported to think and work politically, and plan, reflect and learn in short planning cycles. Internal systems need to empower front line staff, but also exercise effective scrutiny on adaptive decision making. Monitoring systems need to facilitate this internal learning, as well as serving accountability purposes.

approaches, capacities and relationships take time to evolve and can be undermined by pressure for quick wins. Front line staff (and partners) need to be actively involved in analysing their changing context, and monitoring the effectiveness of their activities. They need to be supported to think and work politically, and plan, reflect and learn in short planning cycles. Internal systems need to empower front line staff, but also exercise effective scrutiny on adaptive decision making. Monitoring systems need to facilitate this internal learning, as well as serving accountability purposes.

Develop a very good working relationship with your donor! Adaptive programming is uncertain and risky for all concerned. Good communications, close collaboration and quick turn around on decision making between the donor, supplier and programme staff are all essential.

That, at least, is some of what adaptive programming means for us. If you are interested in learning more, we have written a paper “Adaptive programming in practice: shared lessons from the DFID funded LASER and SAVI programmes”. Further details of how we work and the tools we use are also available on our websites here and here. Our practice is constantly evolving as we learn, and new challenges arise. We are interested in learning from your experience and hearing your reflections of what we do.

September 6, 2016

Is it time for the Aid Community to Explain Itself to Developing Countries?

Thomas Carothers of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace introduces his newly released report,  Navigating International Aid in Transitions: A Guide for Recipients, written with Mark Freeman, Cale Salih, and Robert Templer

Navigating International Aid in Transitions: A Guide for Recipients, written with Mark Freeman, Cale Salih, and Robert Templer

While interviewing the director of a women’s rights NGO in Zambia some years back, I asked her why she thought various foreign groups supporting her organization were present in her country. Her initial answer centered on the UK government, which she suspected of wanting to regain control of Zambia’s copper mines. Not wanting to touch that minefield (sorry), I mentioned her Nordic funders, noting that that they had less of a colonial legacy and, in my experience, a tradition of notable idealism. She smiled ruefully, shook her head, and then offered her own explanation: “I have heard that the weather is very cold in their countries. I think they come here to enjoy the beautiful weather in Lusaka.”

This was from an individual with extensive direct contact with aid providers, in a country where donors had been present for decades. In countries experiencing a sudden aid rush after emerging from dictatorship or civil war, the aid community is often even less familiar to those on the receiving end. Sorting out the different kinds of organizations offering help, their motivations, and their methods—not to mention their underlying interests and longer-term objectives—can be a bewildering challenge. This is true whether the recipient is a newly-minted minister with a waiting room crowded with aid officials, a civic activist pondering the pluses and minuses of seeking foreign help, or an ordinary citizen wondering what all these newly present foreigners are doing in his or her country. And the impact of the frequent misunderstandings is hardly benign or transitory. Dozens of governments are actively demonizing aid providers these days, accusing them of all sorts of nefarious schemes, while taking steps to limit their efforts to work directly with civil society actors or anyone else outside their direct control.

How often and how seriously does the aid community try to explain itself? Not just one institution introducing itself to its intended local partners, but the community as a whole explaining its methods and goals to a wide range of people in a country where it is arriving to help? Or in a country where aid is systematically being misrepresented and vilified?

Intriguing choice of cover image

Several colleagues (Mark Freeman, Cale Salih, and Robert Templer) and I have taken what we hope might be a modest step in this direction by writing a guide for recipients of international aid in transitional contexts. We focused on the areas of aid we know best—aid for democracy-building and peace-building—with the hope that what we put forward on those areas would largely read across to other parts of the aid enterprise.

It was a relatively straightforward idea, but proved less so in practice. Early on, a friend at DFID listened to our plan and exclaimed, “You could get sued!” Though we think that won’t happen, her intuition that trying to “explain” the aid community has many potential pitfalls was correct. A sample of some of the challenges with which we struggled:

Presenting enough information about what is truly an immense community of aid organizations and individuals without burying readers in numbing detail and producing a guide of backbreaking girth.

Identifying the interests that the many different types of aid organizations represent. How, for example, should a potential recipient try to assess the interests represented by a private aid organization that has multiple government funders, a multinational management team, and an independent board of directors made up primarily of diverse financial and political notables?

Finding the right balance between painful descriptions of ways the aid industry sometimes behaves badly and does harm, and heartening assurances that aid can in fact often be helpful and sometimes even invaluable.

Suggesting some genuinely useful ways that aid recipients can push providers to live up to their stated principles and intentions without indulging in unrealistic hopes about sudden improvements in aid coordination, transparency, partnership, and all the rest.

We finished the guide wondering whether and how the aid community can take on the challenge of explaining itself more regularly and thoroughly to those it tries to help, especially in countries where it arrives in a hurry without much prior history. With many decades of aid already behind us, the guide comes terribly late in the game, but aid rushes in transitional countries do keep occurring (Myanmar and Ukraine a few years back, and perhaps Cuba soon?) with all the attendant misunderstandings.

We are strongly convinced of the need to think of these issues in reverse. Trying to solve all (or even most) of the problems on the supply side of international aid has repeatedly failed. Empowering recipients with better information about aid’s many peculiarities, and encouraging them to be more active drivers in their relationships with donors, may be a more promising avenue.

September 4, 2016

What I’m doing in Myanmar – first vlogged installment

Just spent 3 days in Kachin state in the North, trying to get a slightly better understanding of the nature of Myanmar’s conflicts, and implications for trying to improve governance and accountability. Fascinating, but I won’t write anything just yet, as we have a 3 day conference on that topic this week, so will wait a bit longer before blogging. In the meantime, here are some immediate impressions from an IDP (Internally Displaced Persons) camp in the Kachin capital, Myitkyina.

August 30, 2016

Precarious Lives: Food, Work and Care after the Global Food Crisis. Launch of new report, 9th September

Oxfam researcher

John Magrath

profiles a new joint Oxfam/IDS report and tries to convince you to come along to the launch in London on 9th September

the launch in London on 9th September

Duncan has written previously about one of the projects he was most proud of initiating while in (nominal!) charge of Oxfam’s Research Team. This started out as Life in a Time of Food Price Volatility’ and was a four year study of the impact of the chaotic food prices of recent years on the lives of poor people and communities in rural and urban communities in 10 countries. DFID funded it, and the Institute of Development Studies was Oxfam’s main research partner.

Now the project has reached a hopefully grand conclusion and the final report is about to be launched.

“Precarious Lives: Food, Work and Care after the Global Food Crisis” says that though global food price volatility has diminished, the prices that people pay for their food have remained high, demanding a bigger portion of incomes. People are having to work increasingly hard and often in more precarious work to make ends meet and are more reliant now on markets for basic subsistence. As one man interviewed in Pakistan said: “One has to arrange for feeding 10 people and together with rising prices and the lack of employment opportunities, things have become difficult… Even though one is trying to hide these issues they start suffocating the person from the inside”.

So what are the implications for action? This will be the main topic of discussion when the report is launched at 11 a.m. on Friday, 9 September, at Chatham House in London.

Billed as “the end of cheap food and what it means for development” authors Naomi Hossain and Patta Scott-Villiers will speak followed by a panel of experts – Elizabeth Dowler, of Warwick University, Biraj Patnaik of the Indian Right To Food Movement and David Otieno of Bunge La Mwananchi.

Billed as “the end of cheap food and what it means for development” authors Naomi Hossain and Patta Scott-Villiers will speak followed by a panel of experts – Elizabeth Dowler, of Warwick University, Biraj Patnaik of the Indian Right To Food Movement and David Otieno of Bunge La Mwananchi.

Among the issues they will discuss are:

What does the end of the era of cheap food mean for development?

Are universal systems of social protection the answer against the downsides of globalizing development?

What are the politics of social protection and food justice movements arguing for and why?

Without giving the game away too much (we’ll link to the report when it goes live), the report argues that a broader concept of social protection is required by governments. Far from seeing it primarily as a safety net for those at the bottom of society, social protection should incorporate the worlds of work and of care. People in insecure, dangerous, low-paying work – formal or informal – need protections to make that work as safe, secure and reasonably paid as possible. And social protection should relate to the unpaid care roles carried out primarily by women, and often ignored by conventional economics. As more and more women work, and work longer hours, the burdens of also maintaining households and being the principle carers for children are becoming ever greater. As a woman in Pakistan explained: “After coming back from work the body gives in and you don’t feel like working, you feel like lying down and closing your eyes but you can’t because of your responsibilities… Because of my job I cannot take a look if they [my children] are eating properly or not. Because of my work I cannot take care of my son like I used to”.

Social protection according to this thinking should encompass basic services like health, education, water and sanitation and care for children and the elderly – the social and political frameworks within which people can live decent lives.

It should also include protections against bad food and incentives for good food. A perhaps surprising stand-out finding from the research is just how much price shocks and higher prices have speeded up the process of transformation in global diets towards more ‘Western style’ foods; the food that people are increasingly eating is often processed and packaged ‘fast food’ high in sugar and fat.

So whilst there is progress on some development indicators as incomes are generally higher and so are calorie intakes, as Patta Scott-Villiers, one of the authors, says: “Calories and income are being bought at a cost of malnutrition, stress and attenuation of care.”

Malnutrition in the form of obesity is rising everywhere. From Indonesia to Ethiopia, parents interviewed frequently voiced concerns over food safety and high levels of sugar, colourings and additives and said they wanted government restrictions on advertising junk food to children and regimes to guarantee food safety. Unfortunately, from recent experience in the UK we know how difficult that is going to be….

August 24, 2016

See you in September

I’m off to the Edinburgh fringe to direct a cultural firehose onto my parched hinterland, followed by 10 days in Myanmar, where, among other things, I will finally find out the correct adjective – Burmese? Not sure when I will be blogging next, so until then, here’s a pic of each.

August 23, 2016

Is the UN about to agree a new deal for refugees and migrants?

Josephine Liebl

, Oxfam’s global policy lead on displacement, looks ahead to the UN Summit in New York in

September – and looks back on a heady few weeks negotiating its outcome.

The first ever UN Summit on Refugees and Migrants will take place in New York on 19th September. President Obama will host a Leaders’ Summit on refugees the day after. The likely results of the Leaders’ summit are all to play for, but before diplomats headed off for their holidays, they negotiated the document that world leaders will adopt at the UN Summit next month. While it goes some way, the Summit is the start of a long process and not the delivery of the solutions the world is waiting for. What happens the day after and how we hold countries to account over the next two years will be crucial if we are to see the global response needed to address the greatest displacement crisis of our time.

Sitting through the endless negotiations in July, I asked myself what exactly UN Member States and the Secretary General were expecting when they called the Summit. Comparing tracked changes and different proposals, it seemed they had forgotten its purpose: to better protect refugees and migrants and share responsibility for some of the most vulnerable people in the world.

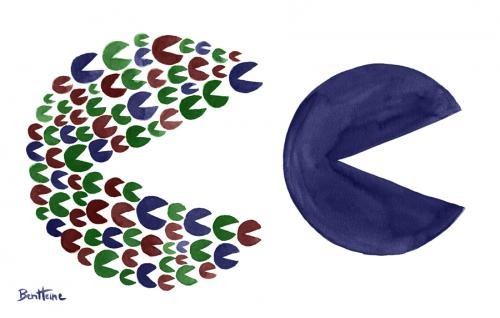

As Oxfam revealed in July, there’s a stunning inequality in how some countries host far more refugees than others, and it’s not based on their ability to cope. The six biggest economies in the world host less than nine per cent of the world’s refugees and asylum seekers while poorer countries are shouldering the bulk of the responsibility. Nobody can pretend the system isn’t broken and that without concrete commitments to do better, nothing will change. But instead of coming up with practical solutions, we – the NGOs listening to the negotiations – were treated to a master class in evading commitments that would help refugees and migrants. Every promise seemed to have a caveat like ‘where appropriate’, every plan something like ‘we will consider’.

As Oxfam revealed in July, there’s a stunning inequality in how some countries host far more refugees than others, and it’s not based on their ability to cope. The six biggest economies in the world host less than nine per cent of the world’s refugees and asylum seekers while poorer countries are shouldering the bulk of the responsibility. Nobody can pretend the system isn’t broken and that without concrete commitments to do better, nothing will change. But instead of coming up with practical solutions, we – the NGOs listening to the negotiations – were treated to a master class in evading commitments that would help refugees and migrants. Every promise seemed to have a caveat like ‘where appropriate’, every plan something like ‘we will consider’.

Upholding rights and fighting xenophobia

The outcome is not all bad. The final document reaffirms international human rights, refugee, and humanitarian law, and governments’ commitment to non-refoulement (not returning anybody to a country where s/he could face cruel, inhumane treatment or persecution). In a world where the right to claim asylum is routinely violated, it’s also important that the Summit also underlines this right. But such reaffirmations are the bare minimum that should be expected from this document – they cannot substitute real progress.

The Summit will also strongly condemn xenophobia, racism and intolerance, and remind the world that diversity enriches every society. That might seem like a statement of the obvious – if it weren’t that countless politicians were saying precisely the opposite.

The document does go further, calling for ‘more equitable sharing of the burden and responsibility for hosting and supporting the world’s refugees’, thereby paving the way for this to be adopted by the UN General Assembly, which takes place just after the UN Summit. But without firm commitments and a clear pathway to act upon them these nice words are meaningless and it is hard to see when the global response desperately needed will come. More people are being displaced by violence than ever before yet governments have so far settled for empty words instead

A bulldozer dismantles shelters on February 29, 2016 in the “Jungle” migrant camp in the French northern port city of Calais. Two bulldozers and around 20 workers began destroying makeshift shacks, with 30 police cars and two anti-riot vans stationed nearby. AFP PHOTO / PHILIPPE HUGUENPHILIPPE HUGUEN/AFP/Getty Images

of action.

Business as usual?

Ban Ki moon called this Summit to change things. But listening to diplomats negotiate, I was repeatedly struck by how many managed to use the negotiations to endorse the status quo, which simply isn’t good enough. The final document refers to the need to strengthen international border management cooperation, including training. Of course states have the authority to control their borders. But it is hard not to be cynical about what ‘best practice’ might look like after recent revelations of the EU’s plan to fund detention centres and equipment in Sudan. There is an unhealthy emphasis on the return of refugees and migrants beyond non-refoulement. Following a proposal by the Africa group, the document even suggests that a government’s decision to return refugees should not be ‘conditioned on the accomplishment of political solutions in the country of origin’. Why? Perhaps to justify Kenya closing a camp for Somalis? The US and other countries insisted on including a reference to detaining migrant children, which undermines hard-fought international human rights standards set by the UN.

Missing out the largest group of people displaced today

But it’s what the Summit will not say that’s so disappointing. People who have been forced to flee and remain within their countries’ borders – Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) – are barely mentioned, despite comprising double the number than that of refugees. . From Syria to South Sudan, Yemen to Nigeria, their plight is often as grave as that of refugees, though often less visible, as Oxfam’s new report on the crisis in the Lake Chad Basin (of Nigeria, Niger and Chad) makes clear.

Responsibility shifted or shared?

The biggest failing of the Summit will be that it won’t agree on any concrete steps for governments to share responsibility for refugees in the future. One of the Summit’s plum results will be a “Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework” which maps out how the international community should respond to current and future refugee crisis.

Asylum seekers protest at Australia’s Nauru detention camp, 2015

But there is nothing in the framework that actually commits states to provide adequate funding. No commitment to welcome or protect a larger share of the world’s refugees or to offer them education and access to work. No commitment to resettle 10% of the world’s refugees, as countries such as Turkey that already host a hugely disproportionate share themselves had been seeking. Without tangible commitments, how much will actually change?

From this document, it is difficult to see what will be different for the world’s refugees and migrants after 19th September. But, President Obama’s separate summit the next day, and his insistence that other world leaders ‘pay to play’ – offering real figures on aid, resettlement and access to education and work– may mean that there will be more progress. Whatever happens, it is clear that these twin Summits will be the beginning, very far from the end, of delivering the change that refugees, migrants, and still more so IDPs need.

The way ahead

Specific solutions will have to be achieved, largely, after September. That is why calls for putting equitable sharing of responsibility into practice will continue after these Summits.

As Prime Ministers and Presidents plan to go to New York next month, they should not limit themselves to whatever lowest common denominator comes out of the UN Summit. Those joining Barack Obama the following day can immediately raise the bar by making more tangible commitments, which is why they need to hear loud and clear that their publics expect them to do more there and beyond.

Once the Summits are over, there will be so much to do. Governments will have to demonstrate that they will share responsibility in practice, including the Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework, so that the millions of people fleeing conflict, violence, disasters and poverty get the support they need. Governments will be negotiating Global Compacts on Refugees and on Migration over the next two years where we need to see more meat on the bone, more tangible change to help the millions of people in need.

We will continue to push for greater ambition in September and hold world leaders to account because what is needed is a humane response, not one borne of ignorance, avoidance and blame.

August 22, 2016

Please comment on this draft paper: theories of change on empowerment and accountability in fragile states

Ouch. My brain hurts. I’ve spent the last month walled up at home writing a paper on ‘Theories of change on empowerment and accountability in fragile and conflict-affected states’ (acronym heaven – ToCs on E&A in FCAS). Pulse racing yet? It’s one of a series of inception papers for a big research consortium on E&A in FCAS, which Oxfam is a member of (IDS is leading, plus various other partners – more detail as the work progresses). The deadline is next month, but I’m off on holiday next week, then swanning around Myanmar, so I thought I’d put up a pretty rough 10,000 word draft and invite FP2P readers to contribute some free consultancy their insights. Here it is – ToCs for E&A in FCAS, Duncan Green, draft for comment, 19 August 2016 – comments by 9th September please, to dgreen[at]oxfam.org.uk.

Ouch. My brain hurts. I’ve spent the last month walled up at home writing a paper on ‘Theories of change on empowerment and accountability in fragile and conflict-affected states’ (acronym heaven – ToCs on E&A in FCAS). Pulse racing yet? It’s one of a series of inception papers for a big research consortium on E&A in FCAS, which Oxfam is a member of (IDS is leading, plus various other partners – more detail as the work progresses). The deadline is next month, but I’m off on holiday next week, then swanning around Myanmar, so I thought I’d put up a pretty rough 10,000 word draft and invite FP2P readers to contribute some free consultancy their insights. Here it is – ToCs for E&A in FCAS, Duncan Green, draft for comment, 19 August 2016 – comments by 9th September please, to dgreen[at]oxfam.org.uk.

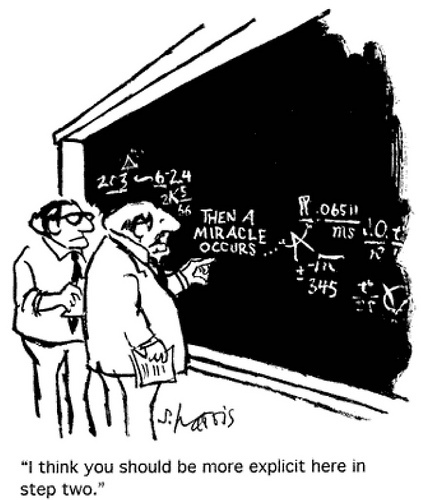

Headlines? Aid agencies (both big donors and INGOs) tend to conflate how endogenous change happens in the social, political and economic system (theory of change) with the process of designing their own interventions (theory of action). There is little apparent interest in how E&A occur in the absence of aid, or in what we can learn from history – basically, it’s all about us.

The lack of attention to context matters because such an institutionally self-centred approach has led to a series of weaknesses and oversights in the design of interventions, which a proper theory of change could help correct. In particular, the greater relative importance in FCAS of critical junctures, non-state actors and informal power.

It’s been a while

There is very little overlap between the literature on FCAS and that on E&A – in fact they routinely ignore each other. That’s part of the rationale for the research programme of course (and props to DFID for spotting the gap and funding the research).

Turning to the Theories of Action, there’s a big gap between theory and practice – aid agencies may talk an increasingly good talk on flexibility, being politically smart and locally led etc, but with the exception of a few highly publicised Potemkin Projects, there’s an awful lot of bog standard E&A work going on with questionable impact. Institutional barriers within the industry are probably the main obstacle to closing the gap.

All the standard approaches to E&A are more difficult and risky in fragile states – citizens shouting at governments (aka demand side) are more likely to be shot, seminars for civil servants don’t work if they have no interest in serving the public in the first place (though I’m sure they’re grateful for the per diems). The responses to that seem to fall into two broad camps – ‘do more’ and ‘do less’ (IDS is going to hate that level of simplicity!).

Do more: Regular FP2P readers will be familiar with this approach: thinking and working politically, doing development differently etc. Study the system, abandon blueprints, find out how things actually work and then ‘work with the grain’ to strengthen E&A when you can.

Do less: two responses here. Either pursuing E&A is a fools’ errand when the risks are this high and the chances of success so low, so just concentrate on influencing ‘elite bargains’ and cross your fingers that stability and growth will eventually lead to ‘trickle down E&A’. Alternatively, abandon the insane hubris of assuming that outsiders can come in, identify the appropriate entry points and engineer reforms in the right direction and concentrate on the ‘enabling environment’, eg via access to information.

The paper is trying to come up with some hypotheses to test in the course of the project – here’s my first stab:

Critical Junctures: E&A work in FCAS will be more effective if it gives greater priority to detecting and responding to critical junctures (whether predictable or not) as drivers of change

Positive Deviance: Including positive deviance as part of due diligence in programme design will lead to a wider range of potentially effective ToAs

Non-State Actors: If different external aid and development agencies can overcome their institutional and ideational obstacles to working with NSAs, their E&A work will have more impact

Theory v Practice: The main obstacle to turning evolving theories of action into programme practice is the institutional design of the aid business. There are examples of re-engineering of incentives and processes that can help overcome these barriers

Lessons of History: More research on the politics and critical junctures that gave rise to ‘turnaround states’ could contain valuable lessons for current approaches on E&A in FCAS

Over to you

August 21, 2016

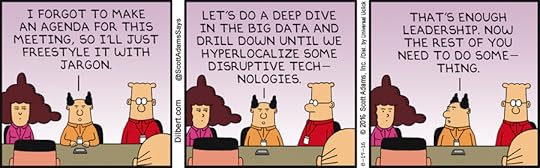

Links I Liked

Invaluable tips for managers who need to wing the next meeting.

Smart idea. Using house prices in Egypt to identify the richest, who are routinely missed by household surveys and tax receipts. Result? Egyptian inequality higher than we thought

Those who read more than 3.5 hours weekly survive almost two years longer than those who didn’t crack open a book (blogs don’t count, sorry). [h/t Bill Easterly]

Those who read more than 3.5 hours weekly survive almost two years longer than those who didn’t crack open a book (blogs don’t count, sorry). [h/t Bill Easterly]

This bag was spotted today in Berlin. It reads:”The only purpose of this text is to terrify those afraid of Arabic.” [h/t Tarek El-Messidi]

What working as an FGM counsellor taught me about female sexuality, by Leyla Hussein

Good. Someone’s taking a gendered approach to panels more seriously than just ‘getting a woman on there’.

So the graph shows most people in US aren’t worried about Zika. Oh wait, hold  on a minute….. [h/t Scoops Maroon]

on a minute….. [h/t Scoops Maroon]

Is Kenya’s crackdown on NGOs about fair wages or silencing critics? The wage gap between nationals & expats is proving to be an Achilles Heel

Yeah, yeah, Usain Bolt was amazing (especially for this Jamaican mother), but here’s the real top moment of the Olympics. Step forward the O’Donovan brothers, Ireland’s viral rowing sensations [h/t Paula Radcliffe]

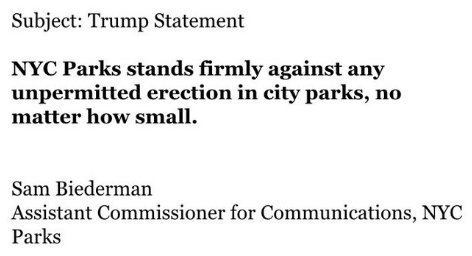

A nd finally, some anarchists put up a nightmare statue of Donald Trump in a New York park, but the best thing about it was the subsequent police statement [h/t James Herring]

August 18, 2016

How do developing country decision makers rate aid donors?

Had a last minute cancellation of today’s post – ah Oxfam sign off, doncha love it? So here’s the most read new post from the last year.

Brilliant. Someone’s finally done it. For years I’ve been moaning on about how no-one ever asks developing country

Anyone ever asked her?

governments to assess aid donors (rather than the other way around), and then publishes a league table of the good, the bad and the seriously ugly. Now AidData has released ‘Listening To Leaders: Which Development Partners Do They Prefer And Why?’ based on an online survey of 6,750 development policymakers and practitioners in 126 low and middle income countries. To my untutored eye the methodology looks pretty rigorous, but geeks can see for themselves here.

Unfortunately it hides its light under a very large bushel: the executive summary is 29 pages long, and the interesting stuff is sometimes lost in the welter of data. Perhaps they should have read Oxfam’s new guide to writing good exec sums, which went up last week.

So here’s my exec sum of the exec sum.

The setting: ‘Once the exclusive province of technocrats in advanced economies, the market for advice and assistance has become a crowded bazaar teeming with bilateral aid agencies, multilateral development banks, civil society organizations and think tanks competing for the limited time and attention of decision-makers.

Development partners bring an increasingly diverse set of wares to market, including: impact evaluations, cross-country benchmarking exercises, in-depth country diagnostics, “just-in-time” policy analysis and advice, South-South training and twinning programs, peer-to-peer learning networks, “engaged advisory services”, and traditional technical assistance programs. Yet, we know remarkably little about how the buyers in this market – public sector leaders from low and middle-income countries – choose their suppliers and value the advice they receive.’

The Findings: Sorry DFID/USAID, but ‘Host government officials rate multilaterals more favorably than DAC and non-DAC development partners on all three dimensions of performance: usefulness of policy advice, agenda-setting influence, and helpfulness during reform implementation. The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, the GAVI Alliance, and the World Bank rank among the top 10 development partners on all three of these metrics.’

The Findings: Sorry DFID/USAID, but ‘Host government officials rate multilaterals more favorably than DAC and non-DAC development partners on all three dimensions of performance: usefulness of policy advice, agenda-setting influence, and helpfulness during reform implementation. The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, the GAVI Alliance, and the World Bank rank among the top 10 development partners on all three of these metrics.’

The Old Boys network is alive and kicking: ‘Host government officials who have previously worked for a development partner usually regard their policy advice as being useful’. Perhaps connected to that, the fear of China sweeping the rest of the aid business aside appears overblown (see fig).

Listening more to developing countries gets more results than forcefeeding them through ‘technical assistance’ programmes: a big econometric data crunch found that: ‘Alignment with partner country priorities is positively correlated with the extent to which development partners influence government reforms. This finding suggests that when development partners put the country ownership principle into practice, they usually reap an influence dividend. [Whereas] Reliance upon technical assistance undermines a development partner’s ability to shape and implement host government reform efforts. The share of official development assistance (ODA) allocated to technical assistance is negatively correlated with all three indicators of development partner performance.’

All good stuff, but I really had to dig to extract these messages. And the report misses the biggest of all tricks – where is the league table? If there’s one thing that’s guaranteed to get the attention of policy makers, it’s finding that they are languishing at the bottom of a table of their peers. The data gathered here could easily be combined to produce an overall table of how different aid providers rank in the eyes of their recipients across a number of factors.

A quick exchange of emails with an understandably unhappy (with this review) AidData established that they did in fact produce a league table after all. But it’s on page 82 of the appendices, under the title ‘Appendix E: Supplemental information.’ At this point, the report starts to look like a classic comms case study, and not in a good way.

So here’s the top 20 on what for me is the most interesting questions. British readers please note, DFID doesn’t make the cut – it’s at 31, 35 and 40 in the 3 columns.

The good news is that AidData is planning similar exercises in 2016 (any update?) and 2018. Let’s hope they sort out some of the teething troubles with their comms (I’m sure Oxfam would be happy to help), so that they make the most of a great idea, a huge amount of hard work and some brilliant data.

More coverage in the Washington Post.

August 17, 2016

What sort of trade campaigns do we need around Brexit?

Not all conference calls are as terrible as the one depicted in ‘a conference call in real life’. Had a really good one yesterday with Oxfam/Exfam trade wonks on the impact of Brexit on Britain’s trade relations. Here’s my take.

Around the early 2000s, I spent about 7 years as a trade wonk, first at CAFOD and then at DFID. Highlights include wandering through the tear gassed battle lines of Seattle, and experiencing a full scale summit collapse in Cancun (here’s a pic of the press room at that moment – it really has to be experienced). So now, are we just going to dig out all our old policy positions and do a kind of ‘Magnificent Seven Ride’ sequel, or should we do things differently this time around?

wandering through the tear gassed battle lines of Seattle, and experiencing a full scale summit collapse in Cancun (here’s a pic of the press room at that moment – it really has to be experienced). So now, are we just going to dig out all our old policy positions and do a kind of ‘Magnificent Seven Ride’ sequel, or should we do things differently this time around?

For trade campaigners the early noughties brought together two often competing narratives. The first was northern liberalization, epitomised by duty free access for poor countries to northern markets, and reform of Europe’s Common Agricultural Policy or US cotton subsidies. The argument there was that northern protectionism was both raising prices for its own consumers, and preventing developing country exporters from trading their way out of poverty. On these issues we had allies among liberal economists in the World Bank, DFID and elsewhere.

The second current of thought was about ‘policy space’. The work of Ha-Joon Chang and Dani Rodrik suggested economic take-off almost always occurs with a degree of protection of infant industries, yet many of those forms of protection were being banned under free trade agreements. The rich countries were either historically ignorant or, in Ha-Joon’s words, were actively ‘kicking away the ladder’ from poor countries. Our allies here were in the UN system, academia and among the developing countries themselves.

Since then, the northern liberalizing agenda has languished, caught up in the backlash against globalization, while the southern policy space argument has got stronger, both because the Washington Consensus has crumbled and because developing countries themselves have asserted themselves in global debates.

Trade policy debate, anyone? Seattle WTO ministerial, 1999

So much for the global picture – what about Brexit? All the UK’s trade agreements currently fall under the aegis of the EU, and become void on the day we exit. That presents the new Department for International Trade, led by Liam Fox, with a vast negotiating task – not just agreeing Britain’s trade rules with the EU, but negotiating new agreements with a range of other partners, including the emerging economies (China, India) and the least developed countries. Let’s assume that China and India are perfectly capable of defending their interests in any talks; it’s the smaller players that aid agencies should mainly be thinking about. In particular Britain will be renegotiating the Economic Partnership Agreements signed by the EU with its former colonies, and may have to come up with an alternative to the EU’s Generalized System of Preferences for LDCs in general (see this excellent post from Emily Jones for more detail).

So much for policy and facts, how about politics? Couple of points to note here:

The academic debate may have moved on, but the mood music in the British Government is very much about using aid to promote British National Interest. When it comes to trade rules, they’re more likely to be interested in promoting UK exports and business strategy than allowing trading partners to safeguard policy space for development.

The Department of Trade is a newly created ministry, and so is both in a state of flux and likely to be horrendously overstretched. That provides opportunities if campaigners are smart enough to adapt their message to these realities. One is to ask them to sign up to some general principles, such as a development audit of draft trade agreements, that costs nothing now, but gives a good basis for debate in the future. Another might be to identify some easy wins for an overstretched department, such as ‘things that you shouldn’t change’ or ‘good ideas you can nick from elsewhere’ – eg the EU provides good access for LDCs which, like Norway, the UK could replicate post-Brexit

So here’s my top three suggestions for viable trade campaigns (not Oxfam’s – this was just an initial conversation.

Male only panel on horseback

There’s a fair chance we won’t agree our strategy until the trade negotiations are all finished and signed…..).

10 easy trade wins for development: provide preferences equivalent or better than the EU’s, create an Africa-wide preference scheme like AGOA, etc

A Development Charter for the Department of Trade: general principles that prove that the UK still cares about the rest of the world

What are developing countries saying? Gather the views, fears and asks of developing country negotiators and civil society, and publish them regularly throughout the negotiations

Plus two other thoughts:

On policy space, we might be better off supporting civil society and governments in developing countries in the negotiations (eg with legal advice) than banging our heads against Whitehall’s rich selection of brick walls. Amplifying voices of businesses that serve the poorest can also be critical, especially as a handful of large businesses (or vested interests) often end up presenting themselves as speaking for ‘the national interest’. We tried to do that the last time around under the rather patronising name of ‘developing country assertiveness’, but institutional pressures (need for media coverage, or campaigns at home) always sucked resources away. Can we do it better this time?

And finally, a dilemma. There will be lots of pressure to include safeguards (labour, human rights, environment etc) in trade agreements. That seems perfectly reasonable at first glance, but I have mixed feelings. A bit like the US constitution, trade rules should be designed with bad guys in mind, not saints. If a safeguard can be abused for short-term protectionist purposes by a British politician, at some point it will be – we should remember that.

Thoughts?

And here’s that conference call in real life – enjoy

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers