Duncan Green's Blog, page 134

September 26, 2016

Do we need to rethink Social Accountability? Thoughts from Myanmar

The main reason for my recent visit to Myanmar (apart from general nosiness) was to take part in a discussion on the

Curse or cure?

role of social accountability (SA) in the rapidly opening, shifting politics of a country in transition from military rule. It got pretty interesting.

The World Bank defines SA as ‘the extent and capability of citizens to hold the state accountable and make it responsive to their needs’. What became clear over the course of the conversation was that in many countries and many people’s minds SA has been reduced to a set of activities/ tools (citizens’ scorecards, public hearings). According to Oxfam’s Jane Lonsdale ‘in Myanmar it is being used in its broadest sense as an entry point to begin working on getting people to talk to each other. In Myanmar even ‘citizens’ and ‘state’ cannot be used, as both are contested, so Oxfam uses ‘people and power holders’ or ‘communities and local administrations’ to take account of the multiple social contracts’. We need to try and think through what actually builds social accountability in any given context, not just assume we can chuck particular activities at everything and hope that they will do some good.

Whose accountability?

One way to escape from the cul de sac is to start in a different place, with the social contract – the bonds of duty and responsibility that bind together different actors (citizens, state, private sector etc). SA is best seen as a set of processes that build the density of the social contract.

For a start, we need to get beyond the typical social accountability binary, in which citizens interact with states, and CSOs are a perfect proxy for citizens. In the conflict areas of Myanmar, there are a series of ‘social contract lines’. Here’s what I came up with for Kachin:

Each of the five actors is in fact a cluster (eg ‘Union Government’ includes national, state and local government), so you could subdivide them endlessly or add in other players (eg private sector, academics, media, faith groups). But be warned, the number of social contract lines proliferates rapidly (for wonks, n(n-1)/2, where n is number of actors). Keeping it simple/simplistic and looking at the 10 lines, it looks like five (marked in red) are already being dealt with through domestic politics, sometimes with the help of the international community:

1↔4: elections, democracy strengthening etc

2↔4: traditional social accountability

3↔4, 3↔5 and 4↔5: peace process

Two (marked in green) are very unlikely to happen given the current levels of fear and distrust: citizens or CSOs engaging with the military.

That leaves 3 (marked in blue) that have largely slipped below the radar:

1↔2: internal accountability of CSOs (except through partner selection)

1↔3: accountability of ethnic administrations

2↔3: CSOs acting as independent checks and balances of ethnic administrations

So one place to start is to think through whether any of these neglected lines ought to enter our plans, and what kinds of approach could be relevant. These approaches may well not involve traditional SA ‘tools’.

What’s different about doing social accountability work in fragile contexts?

The conversations highlighted some important differences between promoting SA in fragile and non-fragile contexts. Number one is risk. It’s all very well talking about trying things out, innovating and ‘learning by failing’, but in fragile contexts, people may get shot if you get things wrong (say if your project stokes up ill feeling). ‘Do No Harm’ becomes an important over-riding consideration.

Number one is risk. It’s all very well talking about trying things out, innovating and ‘learning by failing’, but in fragile contexts, people may get shot if you get things wrong (say if your project stokes up ill feeling). ‘Do No Harm’ becomes an important over-riding consideration.

Local (rather than national) engagement may make more sense in fragile contexts. When we presented a range of Oxfam experience from other countries, it was striking that the example that really resonated with Myanmar CSOs came from the Democratic Republic of Congo, where we support ‘Community Protection Committees’, made up of six men and six women elected by their communities to identify the sources of insecurity and stress and tackle them – for example negotiating a reduction in the number of military checkpoints that demand endless bribes for passage.

There’s also a potential trade-off between building the social contract and promoting transparency. In places like Myanmar, strengthening the social contract is often best done through informal mechanisms – building relationships, having dinner together etc. That’s when people can get to know each other, but also negotiate and make concessions without losing face.

Which bits are accountable?

Even in a conflict-free bit of Myanmar, that affects how we promote SA. After monitoring local authority budgets and then organizing public hearings that allowed the population to raise issues with state officials, CSO partners ended up doing two reports – a public one, and then a private one for local political bosses, where ‘tendering rules were not properly applied’ became specific allegations of corruption. It worked – officials were grateful for the tactful approach and took action, removing 5 officials. But it was hardly transparent.

So is there a danger of ‘premature transparency’? Should we concentrate first on widening the circles of inclusion and trust in relationships, then formalizing those interactions, and only then pursue some degree of public transparency? Or is that just a smokescreen for covering up wrong doing?

In his recent paper, World Bank economist Shanta Devarajan argued that outsiders should focus on promoting an ‘enabling environment’ for SA, and suggested that transparency and access to information were the best focus. Myanmar suggests that info and transparency may not be the best point of entry in building an enabling environment for accountability – other (more political/social, less geeky) areas make more sense.

In particular, the word that recurred throughput my time in Myanmar was ‘trust’ – seeing our SA work as an exercise in broader trust-building, bringing people together to build relationships and ‘bridging capital’ between groups may well be our biggest contribution, rather than rushing to wheel out the toolkits so beloved of SA adherents in many countries.

September 25, 2016

Links I Liked

Beta version of How Change Happens website now live – need your feedback please (and delighted to hear from the  accompanying poll that you aren’t sick of me going on about the book – at least not yet. Give me time…..).

accompanying poll that you aren’t sick of me going on about the book – at least not yet. Give me time…..).

How corporates & NGOs might collaborate to promote tax transparency. Ethical Tax Initiative anyone?

17 rage-inducing bits of aid jargon (robust, circle back, buckets, learnings, take-aways) & what should replace them. Hope someone’s keeping a compilation of these – we need a combo style guide/Academie Francaise language police to defend plain English against the management-speak barbarians.

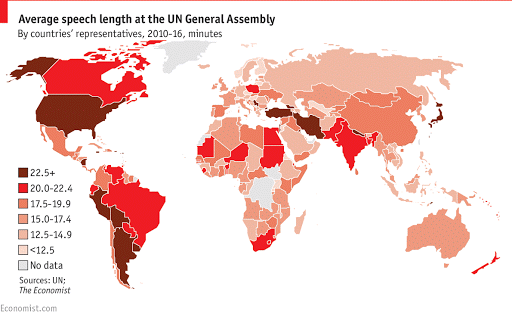

Leaders from the Americas (esp US) talk the longest at the UN

Leaders from the Americas (esp US) talk the longest at the UN

ActionAid had a good week:

What happens when you take up Bridge on their call to visit their schools? Vintage Ben Phillips

Women do four years more work (paid + unpaid) than men in lifetime. Top killer fact from AA

Hard to avoid Syria’s tragic downward spiral this week:

What do Syrians want? Opinion polls inside Syria are impossible, so some bright spark surveyed 2,000 Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Half support opposition, 40% pro Assad + lots more fascinating data

Syrian refugees in Lebanon have become a turning point in the switch to cash transfers in humanitarian aid.

‘Dear President Obama, remember the boy who was picked up by the ambulance?’ 6 year olds make powerful advocates sometimes

September 22, 2016

How Change Happens – need your help with the website and promo tour

Sharp-eyed readers of this blog will have noticed that I have a book coming out (that’s irony, people). 27th October in

1st of many

is the UK publication date, and 1 December in US (don’t ask). First copies are just back from the printer (see pic). Over the

coming weeks, I will be trying to maintain that fine balance between British reserve and authorial desperation – I’m relying on you to tell me if I fail (see new poll, right – I may regret this…….)

I’ll also need your help, following on the triumph in crowd-sourcing the choice of cover and commenting on the draft. First up, the website. Amy Moran, Basheerah Mohamed, Aishah Siddiqa from the Oxfam Policy & Practice team have done a fab job in building a site full of back up materials – case studies, videos etc etc, on the various topics covered in the book, and which will allow readers to suggest their own additions. Before it goes live on 17th October, could people take a look at the beta version and tell us what works/doesn’t work, plus any suggestions for improvements?

You can also now sign up to receive an email alert when the book is available to download: (I promise we’ll only spam you a little)

Website screengrab – what do you think?

Next, the tour, aka From Poverty to Powerpoint. Got off to a great start at VSO yesterday – 80 people in the room, an unknown number online, and all 40 copies duly snapped up. Fingers crossed it carries on like that.

Details of the various events will be updated regularly on the website. My current plans are

October and November: UK

w/b 7 November: Netherlands and Switzerland

28 November – 10th December: Washington DC, New York and Boston

2017 (dates tbd): US West Coast, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, everywhere else.

If you’re interested in hosting an event, and reckon you can muster a decent crowd of book-hungry punters, do get in touch.

After the new year, we’ll be adding in some other stuff – webinars, twitter chats etc. Basically, there’s no escape.

And if you want to try and scrounge a review copy, send an email (including mailing address) to Kate at OUP (kate.farquhar-thomson[at]oup.com)

Over to you.

September 21, 2016

Why the World Bank needs to ask Jim Kim some tough questions in his Job Interview

Guest post from Nadia Daar, head of Oxfam’s Washington DC office

Preparing for an interview is often traumatic – by this point I’ve done a few and believe me, Oxfam doesn’t make things easy! And I’ve heard the World Bank doesn’t either. Yet for the position of president, there is a widespread feeling that Jim Kim’s upcoming interview with the Board of Directors this week is just a formality. There are no other contenders for the position after all, and many of the Board members have already put forward Kim’s name as their candidate of choice. It needs to be a lot tougher than that – the Board needs to seek some firm commitments from Kim when he appears in the hot seat.

Four years ago, the Bank broke decades of tradition by holding an actual process to pick its new president and the fact that there were other candidates being considered gave many of us hope that the status quo had been upended. While an American still ended up with the job, that process gave Jim Kim a certain credibility.

This time around, things have unfortunately gone backwards. Although things technically followed the 2011 process, few would say it truly was “open, transparent and merit-based,” as promised. For the sake of the Bank’s credibility, it is really incumbent on the Board to put in place a clear, predictable process ASAP and well before the next presidential selection.

This time around, things have unfortunately gone backwards. Although things technically followed the 2011 process, few would say it truly was “open, transparent and merit-based,” as promised. For the sake of the Bank’s credibility, it is really incumbent on the Board to put in place a clear, predictable process ASAP and well before the next presidential selection.

So now what? Frankly, Kim is starting with a credibility deficit – he needs to show leadership now more than ever. The Board can play its part by demanding a strong commitment from him that will set the Bank on a path of development relevant to today’s world, that is responsible and accountable, and that places poverty and inequality reduction at the core of an action plan for the years to come.

Early on in his first term, Kim set two goals for the Bank: reducing absolute poverty and boosting shared prosperity. This was the right thing to do for an institution that had for too long focused myopically on economic growth. Now Kim needs to take more decisive action on this agenda:

Development that truly benefits poor communities and women

A second Kim presidency should focus on reducing economic (and gender) inequalities by doing more to help countries improve the quality of their public service delivery and remove financial barriers such as user fees in health and school fees in education. Kim has come out strongly against out-of-pocket payments in health, which the Bank promoted for many years, rightly calling them “unnecessary and unjust” and the Bank has taken important leadership on Universal Health Coverage, but it can do much more to support countries to abolish user fees in public health facilities. We want to see more programs like this one which provides free antenatal care in Nigeria, and a more institutionalized commitment to this approach. The Bank can also do more to help countries mobilize the domestic resources to finance such policies by providing support for the progressive reform of country tax systems.

Development that doesn’t inadvertently do harm

While many – including us – wanted to see a different outcome for the Bank’s new Safeguards regime, the true test

Probably best to stick with suit and tie

will be in implementation and the actual environmental and social outcomes of its operations, particularly in cases of displacement where the Bank has a troubling record. The Bank’s new safeguards mark a change from a “do-no-harm” approach to a risk management one and it will therefore have to improve how it tracks, monitors and supervises its development operations. It needs to resource and recruit highly-trained social and environmental specialists, as well as support countries to improve their own environmental and social frameworks, which the Bank will increasingly rely on. This will be an acid test for Kim’s second term.

Development that is responsible, transparent and accountable

A case that demands urgent reform is the Bank’s lending through financial intermediaries (FIs). Over half of the portfolio of its private sector arm, the International Finance Corporation is invested in FIs that our research has shown often invest in areas that the Bank wouldn’t dare touch directly. This is a highly risky approach with huge loopholes in tracking development outcomes, addressing climate change, and ensuring accountability. In the post-SDGs, post-Paris, post-Addis, era, with new international banks like the AIIB and the BRICS Bank coming online as competitors, pressures are mounting for the World Bank to take risks and to be more innovative with financing. The Board should ask Kim how he intends to manage these pressures while keeping the Bank accountable and responsible.

The interview should cover a lot more than what I can fit in a blog post, but overall, to the Board my message is: demand action from your interviewee, and for Kim: commit to that action plan and put in place the necessary systems to make that happen, including making sure that operations are consistent with the twin goals, allocating resources appropriately, and reforming incentives to make sure staff are prioritizing this agenda.

September 20, 2016

How do you critique a project proposal? Learning from the Experts

A confession – I’m not a programme person. I’ve never run a country programme, or spent aid money (apart from squandering a couple of million quid of DFID’s during my short spell there). So I really enjoyed a recent workshop in Myanmar where a group of real programme people (and me) were asked to critique an imaginary (but not that imaginary) project proposal. It was a great introduction to what it’s like running a programme in a conflict-affected state.

Here’s the proposal:

‘The year is 2016 and a medium-sized INGO is designing a civic empowerment and engagement programme for

Kachin’s the pink one at the top

Kachin state [one of Myanmar’s many conflict zones].

The INGO’s head office in Myanmar is in Yangon [the biggest city] where they employ mostly national staff. International staff members fill senior management and thematic advisory roles. The INGO has been working in Myanmar since 2013, mainly working with local partners to implement projects designed around the INGO’s global civic empowerment methodology in Mandalay and Bago [cities in comparatively peaceful parts of Myanmar].

This civic empowerment methodology aims to educate citizens about their rights and Myanmar’s political system and support Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) to engage with the state government using a variety of tools such as participatory budgeting and public forums.

During the design phase, the INGO made several research trips to the state capital, Myitkyina to speak with ethnic Kachin organizations as well as the Kachin state government. After this, the INGO partnered with one medium-size CSO based in Kachin state, which they provided with training from their global civic empowerment handbook.

During a pilot phase of the project, this CSO was responsible for working with communities around Myitkyina township to educate people about their legal and political rights, organize various social accountability activities, and work with state government officials to build their capacity.

After one year of implementing the project, the INGO was able to secure additional funding to scale up the project outside Myitkyina and began looking for additional partners to implement the project in more townships in Kachin state. They prioritized those townships where their international technical adviser would be able to easily access, so as to comply with the INGO’s internal monitoring policies.

Around the same time, it became clear that many of the priority governance issues for communities the CSO was working with were related to land and so the project introduced specific education about Myanmar’s national land use policy and began advocating to the state government for its implementation.’

Second confession. When I read this, it didn’t seem that bad. Boy was I wrong. As the experts got stuck in, a range of horrendous flaws emerged. Here’s what they came up with:

Who are or what is excluded from the project?

Ethnic armed administrations (who govern parts of Kachin state) – didn’t engage with them in either the design or implementation phase.

Myanmar government-level permissions and buy-in is missing (big oversight in still conflict-ridden and highly centralized system)

Myanmar military is missing in both design and implementation (military a major power in conflict states and across the country – they’ve only just (and partially) handed over power to Aung San Suu Kyi’s party)

Minority non-Kachin ethnic groups are missing from design, and potentially implementation

Fit with governance and conflict context:

Fit with governance and conflict context:

Local context can be very different from township to township.

Why only choose Myitkyina for analysis? May be because of easy access, but better to select the townships you need to do a proper context and conflict analysis.

A key aspect of the context is complete zero trust between government and Kachin citizens- the project isn’t taking this into account, e.g. education about a government policy could be seen as doing propaganda for the government, risking both the imaginary INGO and the partner CSO’s reputation, and probably not convincing anyone

Cannot work on participatory budgeting where there are no budgets and in the middle of a war zone

Positives

Testing through piloting before scaling up

At least they did some initial research, though limited on where they went and who they talked to

Tried to respond to citizens’ concerns by bringing in the land issue

Weakness

Using global handbook and not adapting it

Basing selection on where international staff can access

Putting compliance before the needs on the ground

Risks

Choosing only a single CSO partner is too risky. For example are they Baptist or Catholic (the two main religious groups in Kachin)?

Aligning only to national government and its land policy

Since it probably won’t work, both citizens and government are turned off the whole concept of social accountability: citizen’s expectations are raised, government/KIO aren’t able to respond, both are disappointed

End game not clear: most budget decisions are not made locally therefore what impact on local services is possible?

Impacts on conflict

KIO (the Kachin Ethnic Administration) could feel you are strengthening the state when should be focusing on peace building

How to do it differently?

Need to adapt the tools significantly- cannot roll out what worked in Mandalay and Bago into Kachin, very different contexts.

Need to frame as citizen’s focused, working on their needs, and how they engage with a range of actors (both state and non-state), rather than on citizen-state engagement

Trust building: How do external actors show through their actions that they themselves are trustworthy?

Select communities differently: find an alternative to the international technical support issue

On land: start with what communities are experiencing, and look at a range of processes, not just the policy, but also how it’s informally working. Build a dialogue with what is actually happening. Engage with KIO land policy development

Potentially look at engaging with a less political issue to begin with (land is always tied to economic interests and likely to be an explosive topic).

The exercise left me with even deeper respect for the wisdom and judgement needed to do aid well. It should be an essential part of any aid person’s induction. In particular, the penny finally dropped that this is what ‘conflict sensitivity’ means in practice. Previously it had felt like just another bit of aid jargon – now I realize it is crucial to working in situations where conflict is either already happening, or could be triggered by thoughtless aid projects.

September 19, 2016

Is Trust the missing piece in a lot of development thinking?

I have a kind of mental radar that pings when a word starts cropping up in lots of different conversations. Recently  it’s been ‘trust’, which surfaced throughout my recent trip to Myanmar, but also during a fun brainstorm with Andrew Barnett and Louisa Hooper, two systems thinkers from the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

it’s been ‘trust’, which surfaced throughout my recent trip to Myanmar, but also during a fun brainstorm with Andrew Barnett and Louisa Hooper, two systems thinkers from the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

The search for trust drives a lot of economic behaviour. Enforcing contracts in the court is usually an expensive and unpredictable last resort, much better to conduct business with people you can trust, either because you’ve dealt with them before, or because they have great ratings on ebay or Airbnb. Finding lower cost ways of ensuring trust around contracts is one reason for all the hype around blockchain.

Trust is also at the core of good marketing. Yesterday I chatted to Nilan Peiris, who works for Transferwise, a finance tech company that has disrupted the cosy profit machine of money transfer operators gouging fees out of migrant workers and others, and shot from a turnover of £100,000 per month to £1 billion a month within 3 years. Nilan says 70% of the growth is on friends’ recommendation to friends – a much cheaper and more effective way to build trust than conventional marketing (he’s going to write a post on it for FP2P).

It’s no different in the aid business, a lot of which seems to be designed around overcoming the lack of trust. One way is to minimize the room for discretion – detailed project plan, shopping lists of KPIs and if you can pay by results, so much the better – then the only trust you need is in the people verifying the results.

Umm, maybe

But as we know, that effort to squeeze out discretion results in dumb linear projects that often fail to work in an effective, adaptive way, so people have been developing other forms of trust-building.

The Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, for example, are proactive in choosing their partners (so don’t bother applying if you haven’t been asked), starts small and sees how it goes, and then if it works, they are willing to consider scaling up the funding. That has some positives, especially if the result is core funding that allows organizations to experiment, innovate, adapt and if necessary, fail, without suffering death by logframe.

Another way they get over the trust problem is through networks and ‘trust brokers’. They are usually informal – you’ve never worked with this organization, so you find a friend who has and give them a ring. Sometimes it is more formal – intermediary organizations of, say, social innovators, who can take a look at a proposal and quickly tell you if it makes sense, and if the organization is OK.

Permanent networks are brilliant for generating trust, allowing their members to come together and respond rapidly to events, seizing opportunities for change, as when garment companies, unions and NGOs got together when days of the Bangladesh Rana Plaza disaster to push through a new fire safety accord.

But there are some downsides to these approaches. At worst, it can be a recipe for an Old Boys’ Network that

But how do they stand up?

effectively excludes new entrants, or unusual suspects. What other sources of trust might be available?

An ebay system allowing anonymous reviews of partners, reviewers etc etc?

An equivalent of microfinance arrangements where trust is built on the social pressure on borrowers to repay loans

Andrew Barnett also remarked that grants to individuals rather than organizations can sometimes generate higher levels of trustworthy behaviour, which raises the question of why the aid business is so reluctant to fund individuals rather than institutions. Even when we acknowledge that we are really funding an outstanding individual, we usually insist they cloak themselves in an organization before we sign a cheque – why?

As for Myanmar, I ended up concluding that ‘trust-building’ in an exceptionally low trust environment is (or should be) our overarching purpose. That starts with us – why should local people and organizations trust us? What have we done to earn it, in terms of our behaviours and lifestyles? Taken seriously, that would entail developing good ways to map trust: where do we have existing trust links? What can we do to build trust?

Trust-mapping may also provide a way into responding to shocks and other ‘critical junctures’ in risky environments. Such moments may be windows of opportunity, as political actors churn, change allegiances and accept new ideas, but in fragile contexts they are also high risk – people threatened by change and uncertainty may lash out. Outsiders could minimize the risks involved in responding to such moments by starting with their existing trust links, rather than trying to initiate new relationships and initiatives.

Thoughts? Is trust-mapping already a thing, and if so, any links to guides/examples?

September 18, 2016

Links I Liked

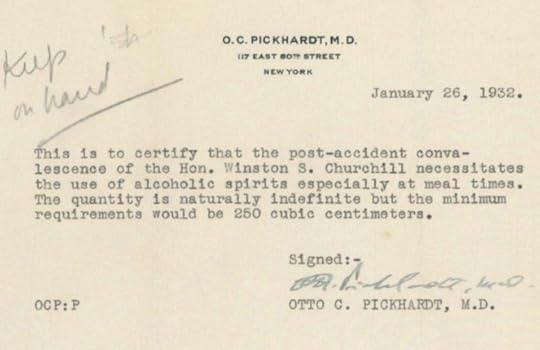

Politicians’ medical reports aren’t what they were [h/t Amol Rajan]

Unleash your inner geek – introducing Real Geek, Oxfam’s new blog on monitoring & evaluation

High Level UN report criticises pharma industry, abuse of intellectual property laws and calls for rethink. Props to Oxfam’s Winnie Byanyima and Mohga Kamal Yanni for their influence.

Gig economy heads South. Uber-type apps for domestic workers (maids, cooks, gardeners) are now emerging in countries like India, Mexico and South Africa.

Doonesbury’s crystal ball. This is from November 1999. Extraordinary. [h/t Ziya Tong]

Doonesbury’s crystal ball. This is from November 1999. Extraordinary. [h/t Ziya Tong]

Choices, choices. Brilliant advice to would-be students from Chris Blattman on making the most of college, whether to go to grad school, should you do a PhD. Plus some useful tips on landing the first job in aid/development after all that study.

Someone put up this awful sign, and now the people who live here call the place they live “Low Cost Village”. Really. [h/t Ben Phillips]

Fascinating 18 month study of how UK Health Departmen policymakers access knowledge and advice. Must read for  advocates.

advocates.

Mamie’s Dream: in virtual reality (use the navikeys, but you really need a headset). One woman’s story of FGM, prejudice & empowerment. New film by my tech innovator sister-in-law Mary Matheson. Any other VR films emerging in the aid biz?

September 15, 2016

Is ‘fragile and conflict-affected state’ a useful way to describe Myanmar?

After spending ten days there earlier this month, I barely even understand the question any more. Nothing like

That’s Myanmar on the right

reality for messing up your nice neat typologies, or in this case, complicating my efforts to finalise a paper with the catchy title of ‘theories of change for promoting empowerment and accountability in fragile and conflict-affected states (FCS)’.

That paper defines FCS as ‘incapable of assuring basic security, maintaining rule of law and justice, or providing basic services and economic opportunities for their citizens.’ So does Myanmar qualify?

At first sight, definitely. Myanmar is plagued by long-running civil wars along largely ethnic lines. We spent 3 days in the northern state of Kachin, home to an armed conflict that kicked off when the Beatles were still looking for their first recording contract (1961). The national government’s writ does not apply in large areas of the state, which are run by the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO) and its armed wing, the KIA.

Over the whole country there are dozens of long-running ethnically-based insurrections against the central government, although the election of a democratic government, led by Aung San Suu Kyi, has triggered hope in a peace process – talks were under way during my visit.

But even under ASSK, central government has maintained its traditional centralized, controlling tendency. The result is a brittle equilibrium between ethnic unrest and central control (both are mutually reinforcing), with neither the trust nor the institutions to allow for peaceful evolution; any misstep or misunderstanding could aggravate the conflict.

Kachin Independence Army

The conflicts are primarily ethnic (Myanmar has 135 different ethnic groups), sometimes buttressed by religion (Baptists, Catholics, Buddhists and the unhappy Muslim minority in Rakhine, which has prompted media coverage worldwide). Programmatic politics, based on more widely shared social identities, is nowhere to be seen, but politics based on ethnicity alone holds little promise of producing stability, because every ethnic minority includes even smaller minorities within its geographical boundaries. Autonomy for the Kachins just turns the spotlight on the rights of non-Kachin ethnic groups within the state.

Myanmar’s plentiful natural resources (jade, gold, timber, opium) layer the ‘curse of wealth’ over this panorama. Both the army and the Ethnic Armed Organizations have traditionally drawn money and power by controlling the production and/or transport of these, producing a difficult political economy where major interests are potentially threatened by the end of conflict.

But what struck me about Kachin was the level of stability of the conflict, or at least ‘organized chaos’ in the title of one report: this was not some shapeless, unpredictable mess like Somalia or Eastern DRC or South Sudan. We found a striking degree of cohabitation between ethnic armed groups and government: we visited the large KIO office in the (government-controlled) state capital Myitkyina and spoke to a KIO Central Committee member, who very kindly

Who you calling fragile?

photocopied the KIO departmental organigram for us – what kind of civil war allows one side to openly hold court on the other side’s turf? The KIO-run hydro company supplies electricity to government-controlled areas (Myitkina has one of most reliable electric supplies in the country), and the government authorities duly pay their bills. Weird.

There are of course dangers in generalizing from Kachin – every conflict in Myanmar is different, some are much bloodier, others more chaotic, some are closer to peaceful resolution.

Overall conclusion? ‘Fragility’ means lots of different things in different parts of Myanmar. In the rapid process of political change that has led to the new NLD government and rekindled the peace process, we heard consistently that both local officials and elected representatives don’t really understand their roles – and that the relations between the different levels of government are shifting and evolving unpredictably as everyone tries to figure out what decentralisation actually involves. All this in the shadow of a still powerful military. Meanwhile, civil society organizations are trying to work out how to adapt to this fast-changing environment.

The conflict-affected parts exhibit different types of fragility, from the parallel administrations of Kachin to drug warlords to fragmented militias and armed groups.

Can you find Myanmar?

So first, let’s talk about fragile contexts rather than fragile states. And second, let’s unpack the different kinds of fragility, perhaps building on last year’s OECD report that set out five clusters of fragility indicators; 1) violence; 2) access to justice for all; 3) effective, accountable and inclusive institutions; 4) economic inclusion and stability; and 5) capacities to prevent and adapt to social, economic and environmental shocks and disasters. Can you find Myanmar on their diagram?

And a final question to any regional gurus. It’s not just Myanmar – North-East India has a long running set of ethnic conflicts of its own. Taken together, this arc of conflict feels quite unique – any explanations? Is it some combination of mountain hideaways, ethnic fragmentation and incomplete state-building or is there some other explanation? Would love to hear some theories.

Big thanks to Tom Donnelly and Jo Rowlands on this post

September 14, 2016

The world’s top 100 economies: 31 countries; 69 corporations

The campaigning NGO Global Justice Now (formerly World Development Movement) have done us all a favour by updating the table comparing the economic  might of the largest countries and corporations. Headline finding? ‘The number of businesses in the top 100 economic entities jumped to 69 in 2015 from 63 in the previous year’ according to the Guardian’s summary.

might of the largest countries and corporations. Headline finding? ‘The number of businesses in the top 100 economic entities jumped to 69 in 2015 from 63 in the previous year’ according to the Guardian’s summary.

The last such table that I know of was produced by the World Bank, and became one of FP2P’s all time most read posts (it included cities as well as countries, which made it even more interesting).

People complained that the Bank table compared apples and pears – national GDP and corporate turnover. GJN have tried to do a better job by comparing government revenues (from the CIA World Factbook – always a treat to see an anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist NGO like GJN using that as a source), and corporate turnover (Fortune Global 500 – ditto). That reduces the country figure – in the case of Argentina, revenues come to about 30% of GDP, generally a higher slice for developed, and lower for poorer countries, and so boosts the relative importance of transnationals. Is that a fairer comparison? Over to the number crunchers on that one.

GJN released the figures in a pretty unfriendly format, so I tweeted to ask someone with more time/IT skills to tidy it up, and Jay Goulden kindly answered the call (I think he was on a particularly boring conference call or something). Thanks Jay.

Enjoy. Countries in black, corporates in the red (as if). The pattern that emerges is of a top tier of some dozen national economies, but below them, pretty soon you get into a sea of red corporates.

September 13, 2016

Please help sharpen up the World Bank’s theory of change on governance and law

The World Bank is helping us hone our speed reading skills this week, by publishing a draft of its forthcoming World  Development Report 2017 on Governance and the Law and asking for comments by Friday.

Development Report 2017 on Governance and the Law and asking for comments by Friday.

Someone has helpfully put a track changes version online here, comparing the new (‘green cover’) draft with the previous (‘yellow cover’) one, which I blogged about in July, but it’s still a pretty mind bending task. My skim of the overview and chapters on elite bargains and civil society engagement suggest that with a couple of minor exceptions, the new draft seems to have retained the good stuff and done little to address the gaps I identified last time around.

Might post more in a couple of days once I’ve had a few more days to digest all this (along with a few other Oxfam wonks who are trying to read it). For now, one of the questions that I’m pondering is how to make sure this WDR has impact on decision makers. In other words, how much attention can such a paper get and what more could be done to turn this into action? This because, despite it’s considerable merits, the report lacks a memorable meme, diagram or proposition that will stick in people’s heads, and find its way into policy papers and decision-making over the next few years.

The closest it comes is this Box in the overview. So I thought I’d put it up and see what people think, and whether you have any suggestions for improving it – and that does not necessarily mean making it more complicated! Comments at the bottom of this page welcome but also send your thoughts to the Bank before Friday if you can. Here we go.

‘What does the WDR 2017 framework mean for action?

The policy effectiveness chain This Report argues that policy effectiveness cannot be understood only from a technical perspective, but rather must consider the process through actors bargain about the design and implementation of policies, within a specific institutional setting. The consistency and continuity of policies over time (commitment), the alignment of beliefs and preferences (coordination), as well as the voluntary compliance and absence of free riding (cooperation) are key institutional functions that influence how effective policies will be. But what does that mean for specific policy actions?

Figure 0.10.1 presents a way to think about specific policies in a way that includes the elements that can increase the likelihood of effectiveness. This “policy effectiveness chain” reads from right to left, starting with a clear definition of the objective to be achieved and following a series of well-specified steps.

Step 1 What? Define the development objective.

Step 2. Why? Identify the underlying functional problem (commitment, coordination, cooperation).

Step 3. Which? Identify the relevant entry point(s) for reform (incentives, preferences/beliefs, contestability).

Step 4. How? Identify the best mechanism for intervention (menu of policies and laws).

Step 5. Who? Identify key stakeholders needed to build a coalition for implementation (elites, citizens, international partners).

My thoughts: this has elements of a good power and systems approach, starting with a problem and context analysis, looking at the policies that might drive change, and mapping out the stakeholders, but it has some major gaps.

It operates almost entirely on the Right Hand side of the Rao Kelleher framework, (below) i.e. the formal side. Often, governance

problems involve the left hand side, in the world of informal power (social norms, people’s sense of ‘power within’ – assertiveness, confidence, agency)

problems involve the left hand side, in the world of informal power (social norms, people’s sense of ‘power within’ – assertiveness, confidence, agency)It seeks to identify drivers of change, and build coalitions around them (good), but where are the blockers and what does the report advocate in terms of overcoming them?

I suspect there are others, but weirdly for England in September, it’s too hot, and my brain has shut down – anyone care to help? The prize is a World Bank endorsed view on governance and institutional reform that could be really influential – get stuck in. My advice to the WDR team is get a brainstorm going on the big idea, with the right combination of wonks and comms people in the room – it will pay dividends.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers