Duncan Green's Blog, page 130

November 21, 2016

Where has the Doing Development Differently movement got to, two years on?

The DDD crew reassembled in London last week, two years on from the Harvard meeting that really got the ball  rolling. Unfortunately I could only attend the first session and the next day’s post mortem, so other participants, please feel free to add your own impressions/put me right.

rolling. Unfortunately I could only attend the first session and the next day’s post mortem, so other participants, please feel free to add your own impressions/put me right.

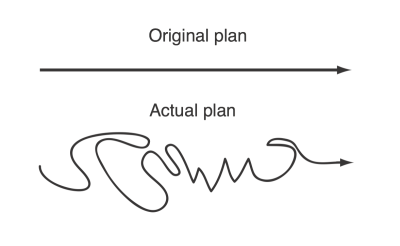

DDD is evolving fast into something approaching a big tent movement. At its core are principles of iteration, adaptation, using systems thinking. If you want to know more check out the DDD manifesto and website. See also this great post by Alan Hudson and Dave Algoso, clarifying the areas of overlap and difference between the various movements. Here’s a 4 minute collection of worthies at the Harvard Meeting (including me) trying to define DDD.

The main players are an interesting bunch: a non-exhaustive list includes donors and multilaterals (DFID, World Bank, OECD, UNICEF); thinktanks (ODI); academics (Harvard, Birmingham); specialist institutional reform agencies (AGI); innovation hubs (Reboot, Feedback Labs) and Humanitarian NGOs (IRC, Mercy Corps). Development NGOs are conspicuous by their absence (some thoughts below).

There has been some rapid progress over the last two years, moving rapidly from theory to practice, with lots of pilots and testing going on – I can’t keep up with the output of country case studies, think pieces etc etc. Is DDD just another passing fad? Probably not, because it has not emerged at the whim of some bureaucrat or spin doctor in New York or Washington, but out of lived practice and experience, including the failures of traditional approaches.

The conversations revealed some fascinating challenges, including:

The double edged sword of aid: Parts of DDD have been driven by/are reliant on donor funding, but this is a mixed  blessing to put it mildly. Reforming the aid system to make it compatible with DDD is a massive exercise, and means sailing against some powerful headwinds right now. While there are examples of reforms efforts underway in some of the big aid agencies, several speakers argued that it is better to sidestep the official aid system altogether, find support from developing country governments keen to find better ways to drive change, maybe turn to foundations for funding (they are more flexible than official donors). But also ‘if you want to innovate, take a couple of zeroes off’, in the words of a Brazilian mayor. DDD requires skills like facilitation to identify problems and convene lots of different players to solve them, and lots of time, but big money is often neither necessary nor particularly helpful. Getting beyond aid would also help get beyond the increasingly redundant North-South division – governments and other players everywhere want to do this stuff.

blessing to put it mildly. Reforming the aid system to make it compatible with DDD is a massive exercise, and means sailing against some powerful headwinds right now. While there are examples of reforms efforts underway in some of the big aid agencies, several speakers argued that it is better to sidestep the official aid system altogether, find support from developing country governments keen to find better ways to drive change, maybe turn to foundations for funding (they are more flexible than official donors). But also ‘if you want to innovate, take a couple of zeroes off’, in the words of a Brazilian mayor. DDD requires skills like facilitation to identify problems and convene lots of different players to solve them, and lots of time, but big money is often neither necessary nor particularly helpful. Getting beyond aid would also help get beyond the increasingly redundant North-South division – governments and other players everywhere want to do this stuff.

How state-centric should DDD be? A lot of the thinking behind it (see books by Matt Andrews, Brian Levy and others) springs from a rethink of previous failed attempts to improve the quality of governance. Although DDD draws quite a bit from private sector approaches e.g. agile technology, management theory (e.g. for problem identification), some of the most dynamic DDD practitioners, like Harvard’s Building State Capability programme, use them to improve effortst to reform governments. It would be helpful to clarify which aspects of the DDD agenda copy across to working on private sector, civil society or other non-state actors.

This is particularly important in working out how DDD works when states are predatory or hostile to reform – an area that is only going to increase in importance for the aid and development sector. Part of the answer there is likely to involve an increased role for non-state actors.

Where are the INGOs in all this? The humanitarians are stepping up, perhaps because they are more used to working in an adaptive, flexible way in response to more unpredictable, chaotic situations, but the development NGOs seem largely absent and/or silent. Oxfam and other INGOs are doing lots of interesting things in this area, though we don’t brand them as DDD – multi-stakeholder initiatives, convening and brokering, trying to encourage innovation, redefine success (eg by learning how to ‘count what counts’ – women’s empowerment, influencing) and make more use of real-time evaluation. But all too often, in practice this runs up against the pressures of competitive funding bids, which push us to drop all the fancy stuff and stick to plain vanilla, linear projects. DDD requires advanced project management skills, when in many countries it’s hard enough to find the basics. And most baffling and frustrating of all, the many one-off examples of innovation and DDD, usually down to some entrepreneur or maverick who has managed to slip in below the radar, rarely seem to spread.

Where are the INGOs in all this? The humanitarians are stepping up, perhaps because they are more used to working in an adaptive, flexible way in response to more unpredictable, chaotic situations, but the development NGOs seem largely absent and/or silent. Oxfam and other INGOs are doing lots of interesting things in this area, though we don’t brand them as DDD – multi-stakeholder initiatives, convening and brokering, trying to encourage innovation, redefine success (eg by learning how to ‘count what counts’ – women’s empowerment, influencing) and make more use of real-time evaluation. But all too often, in practice this runs up against the pressures of competitive funding bids, which push us to drop all the fancy stuff and stick to plain vanilla, linear projects. DDD requires advanced project management skills, when in many countries it’s hard enough to find the basics. And most baffling and frustrating of all, the many one-off examples of innovation and DDD, usually down to some entrepreneur or maverick who has managed to slip in below the radar, rarely seem to spread.

I wondered if this was because INGOs are too big for the small things (taking supertankers white-water rafting) but also too small for the big things (big service providers like Palladium managing massive donor grants, with the capacity and permission to try out DDD, less subject to the strictures of the ‘sticky middle’ of middle managers with their logframes and best practice guidelines)?

Overall, the conversations left me very excited. Visions of dispersed networks of DDD thinkers and facilitators (mainly local), working with local governments, civil society organizations, private sector groups and others to get change processes up and running. What costs there are could be covered by a combination of those using the service, and top ups from suitably flexible forms of aid (eg funding facilities for DDD processes, potentially a ‘switchboard’ or server to matchmake between demand and supply, peer to peer networks of reformers supporting each other). Cool stuff, and I think more organizations and individuals need to get on board.

November 20, 2016

Links I Liked

Tis the season to be evil? A fitting end to 2016 – bring the kids

Next week (starting 28th Nov) I’ll be pestering the US about How Change Happens (actually, I think they might already be wondering about that). Events in Washington DC, New York and Boston. Will try and get a list of event links up on the book website in the next couple of days.

My twitter feed has been crammed with some musings on the deeper significance of /what happens next after the US elections. Some of my favourites have been Sina Odugbemi, in the custody of angst, Kieran Breen on Hypernormalisation and building a global movement for change, Robert Skidelsky on whether this is a 1914 moment and how to avoid what followed and Shashi Tharoor on the end (or at least decline) of US soft power. Bill Easterly reckons it’s time to end the alliance of the War on Poverty with the War on Terror (hard to argue with that). While Jonathan Glennie concludes that after Brexit and Trump, the aid and development sector must pay more attention to domestic (i.e. northern) issues.

What else should I be reading on the ‘how change happens’ of the US elections, on my plane this weekend? Advice welcome

Meanwhile, in these angst-ridden times, how about some good news?

“The number of people in extreme poverty fell by 130,000 since yesterday” should have been the headline every single day in the last 2 decades.

Scandinavia fines people for traffic violations according to their incomes, so Reima Kuisla, a Finnish businessman recently had to cough up $54,000 for going at 65 miles per hour in a 50 zone. How cool is that? [h/t Max Lawson]

Proud Dad spot: props to East London Community Land Trust & its co-Director Calum Green for producing low cost homes whose price is linked to local average wages

Global deaths due to terrorism fell by 10% last year. Don’t suppose that will be on many front pages

Global deaths due to terrorism fell by 10% last year. Don’t suppose that will be on many front pages

And GSK tops a new Big Pharma league table on access to medicines in developing countries

November 17, 2016

It’s International Men’s Day tomorrow – here’s why it’s a bad idea

Tomorrow is

International Men’s Day

, but

Gary Barker

isn’t celebrating

I’m sure it was well-intentioned when International Men’s Day began over a decade ago. The day, in part, aims to draw attention to men’s and boy’s health; this year’s theme is “Stop Male Suicide”. This is a worthy goal: men die earlier and are more likely to face chronic illness and less likely to care for their health that women are. We are more likely to die on the front lines in wars and conflicts. We (men) are less likely to go for HIV testing and treatment when we are HIV-positive. We are more than 80% of the nearly 500,000 persons who die every year from homicide, and in richer countries, three times as many men die by suicide than women, with men over 50 particularly vulnerable. I have spent much of my career writing about and studying these issues. I founded a nonprofit organization that is dedicated to working on them.

But here’s why I don’t believe in the day: it’s also “an occasion for men to celebrate their achievements and contributions […] while highlighting the discrimination against them.” As a whole, it puts the focus on individual men and not on the roots of the problem. It asks us to pat our backs, while identifying our victimhood. It suggests that somehow we as men deserve attention alongside other international causes from advancing human rights, to honoring peace-making individuals, to honoring causes that are urgent for saving our planet.

Hold on a minute, men.

Really?

Absolutely, individual men have problems, and the gendered expectations of how men should be (strong at all costs, silent in the face of pain, self-sufficient) are part of this. All these examples of men’s health issues and vulnerabilities are real and need urgent attention. They matter, for the men whose lives are cut short, for those who don’t go for HIV testing and treatment, and for those who kill themselves and kill other men. They matter for the women and girls who are often pick up the pieces and hold families together.

And, yes, men need help and we need to learn how to ask for help. I survived a malignant cancer eight years ago because I went for early testing and treatment. My oncologist looked at me with an air of wonder. He said he had rarely seen men who did the tests they asked were to do on time, who picked up the results and did all the follow up—on time and as recommended. He was much more used to men dying earlier from cancer than women, being far less likely to ask for help than women and less likely to make the lifestyle changes needed to recover from cancer: we as men are horrible at taking care of our bodies.

However, in a country (the U.S.) which just revealed itself to be full of white men (and women), supposedly the ones  with the power and privilege, who voted for a campaign in part built on discrimination toward women, minorities, the LGBTQI community, Muslims, and many other groups, I find it more difficult than ever to emphasize (or give a pass to) this men-as-victims narrative.

with the power and privilege, who voted for a campaign in part built on discrimination toward women, minorities, the LGBTQI community, Muslims, and many other groups, I find it more difficult than ever to emphasize (or give a pass to) this men-as-victims narrative.

We need to work harder than ever before to call out patriarchy, and, even more precisely, how patriarchy interacts with poverty, privilege and inequality. The word patriarchy feels outdated to some men; for others it feels accusatory. For sure, patriarchy is too often over-simplified to refer to all men having power over all women. We all know, though, that this analysis doesn’t work – the white woman head of the CEO in NYC has more power (and much more income) than her Pakistani immigrant Uber driver. And the white, male (or white female) head of state in Western Europe has much more power than the Syrian man who risked his life to cross the Mediterranean Sea in an overcrowded boat to seek asylum in that white man’s, or white woman’s, country. Not all men have an equal portion of power. Some have very little, if any. Patriarchy also pits groups of men against other groups of men.

The problem starts, as sociologist Michael Kimmel tells us, when angry (and often lower middle income) men – those who showed up on November 8 in the U.S., and have been making their presence known in other countries around the world (promoting the ousting of progressive President Rousseff in Brazil, and cheering for Brexit in the United Kingdom) – feel they have lost something they think they exclusively were due: stable employment and respect.

Hipsters feel pain too

Men (and women) lacking work – the men who feel they have no identity and no worth – have a legitimate grudge. The erosion of welfare states, profits before people, the simplistic notion that those who are out of work are the victims of their own laziness, deserve protest. But turning that anger into an exclusive victimhood on the part of angry (white) men ignores legacies of sexism, racism, and other historical inequalities and those who have experienced them. All men and women, of all ethnicities, deserve dignified work, not just men, or white men.

This is why I don’t support International Men’s Day. What I would support – as a straight, cisgender, white man – is an International Day to End Patriarchy and Unearned Privilege, or the International Day to End Hegemonic Masculinity.

On that day, I would celebrate the women and men who make it possible for women and men to care for their children equally. I would celebrate the women and men, boys and girls, cis- and transgender and across the spectrum, who work to end violence by men against women, by men against men, by adults against children, by police against young black men, and all kinds of violence. I would celebrate the individuals and organizations, and governments and corporations, that work to end homophobia and transphobia. I would celebrate the women and men who treat health care, for women and men boys and girls not as a commodity to be sold but as an undeniable human right.

On the International Day to End Hegemonic Masculinity, I would celebrate the policy-makers who support equal  and paid parental leave for mothers and fathers and all caregivers of their elderly parents. I would celebrate those who work to end violence and who respect human rights every day. I would support those women and men who understand how poverty and inequality interact with ethnicity and historical oppression, and those who work to bring their countries to peace.

and paid parental leave for mothers and fathers and all caregivers of their elderly parents. I would celebrate those who work to end violence and who respect human rights every day. I would support those women and men who understand how poverty and inequality interact with ethnicity and historical oppression, and those who work to bring their countries to peace.

So in this year of angry men’s (and some angry women’s) voices, how about a day that celebrates our common humanity or one that celebrates an ethic of caring about what we share as women and men, cis- or trans, young or old? How about a day that stops pitting men against women but finds our common cause in achieving gender equality and social justice? That would truly be a day worth celebrating.

Gary Barker is President and CEO of Promundo , a ‘global leader in promoting gender justice and preventing violence by engaging men and boys in partnership with women and girls.’

November 16, 2016

Some highlights from the first 30 book launches for How Change Happens

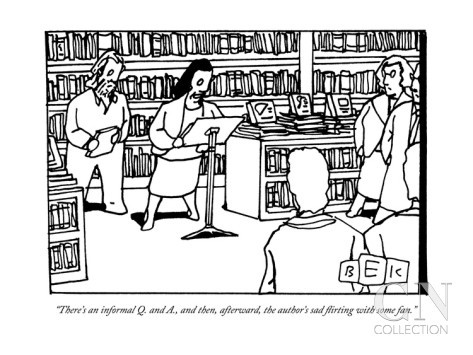

I’m about six weeks into launching How Change Happens, and am having a great (if knackering) time. Highlights so far include a Kurdish/Dutch guitar combo warming up the crowd in Nijmegen, conversations with an Islamic finance entrepreneur trying to do financial inclusion in South Wales, a great group of women managing a community-run service station on the M5 motorway and a network of ‘social leaders’ in the North-East of England who were completely outside the aid and development bubble, but totally got what the book is about. Plus being asked ‘do you believe in the perfectability of the human species’ in Q&A at a predictably erudite launch at Blackwells bookshop in Oxford…..

far include a Kurdish/Dutch guitar combo warming up the crowd in Nijmegen, conversations with an Islamic finance entrepreneur trying to do financial inclusion in South Wales, a great group of women managing a community-run service station on the M5 motorway and a network of ‘social leaders’ in the North-East of England who were completely outside the aid and development bubble, but totally got what the book is about. Plus being asked ‘do you believe in the perfectability of the human species’ in Q&A at a predictably erudite launch at Blackwells bookshop in Oxford…..

Impressions so far? A lot of ‘practitioners’ are finding the book reassuring – it seems to back up their instinctive (and widespread) concerns about the direction the aid business has taken and how to put it right.

Some of the most thought provoking events have involved discussants – academics who read the book, then come back at you with probing criticisms and questions. It’s a bit gruelling having these kind of public vivas, but very productive. Three examples:

SOAS’ Mushtaq Khan argued that it’s all very well talking about positive deviance and looking for successful outliers, but what if there isn’t anything very positive going on? Aren’t these approaches essentially incremental, rather than transformational ? We also need to think about how aid or other interventions can catalyse big structural leaps.

SOAS’ Mushtaq Khan argued that it’s all very well talking about positive deviance and looking for successful outliers, but what if there isn’t anything very positive going on? Aren’t these approaches essentially incremental, rather than transformational ? We also need to think about how aid or other interventions can catalyse big structural leaps.

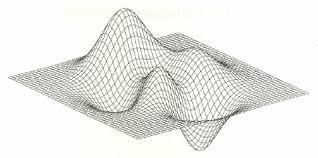

That got me thinking about an idea that I toyed with introducing in the book, but then abandoned as just too geeky. Fitness landscapes. These are used in evolutionary biology to visualize the relationship between genetic make-up and successful reproduction/survival. The more successful you are, the higher you are up a peak, with the different peaks corresponding to different species – two peaks close together could be two species of Darwin’s species, two far apart could be a finch and an elephant. (Feel free to tell me that I’ve got this completely wrong, btw – I’m expecting it).

Mushtaq was arguing that in development, positive deviance looks at how to move higher up on a given peak, but

Fitness Landscape

doesn’t capture the jumps between peaks achieved through structural change. I’m not sure that’s entirely true – positive deviance would also detect new peaks that have emerged spontaneously, for example a new business model or form of immunity to disease – but I take his point that overall, you are looking for positive change within the existing system, rather than major transformation of the system itself. In a follow up email exchange, he elaborated further: ‘The point about positive deviance is not just about missing distant peaks but also nearby peaks that haven’t sprouted yet. There must be a thought process for the potential leader to think through the chances of success and the implications for the poor of some new initiative. Positive deviance isn’t a substitute for that analysis. Positive deviance does however tell us about opportunities that shouldn’t be missed.’

The other point from Mushtaq that hit home was on power. The book argues that power is an all pervasive ‘developmental force field’ and that one key task for any activist is to render power visible in all its many guises (hidden, informal, visible etc). But it also takes what Mushtaq saw as a fairly crude line that redistributing power is the underlying purpose of development – in any given situation, an activist should seek to equalize that distribution by regulating/curbing the activities of those with too much power, and helping those with too little to organize and be heard. Given that I had just been slagging off conventional aid projects as linear approaches to complex systems, wasn’t that a very linear approach to a complex system, asked Mushtaq? Ouch.

Examples he cited to show that moving from less to more equal distribution of power is not always the best choice: what if empowering one group disempowers another? Or when rulers use nominally empowering measures such as decentralization to weaken their opponents in the capital? Or if a short term empowerment (the Arab Spring in Egypt or Syria, say) leads to a backlash and overall massively negative results for poor people? And given that the book also talks about the importance of leadership, what level of hierarchy (i.e. power imbalance) is optimal? Ouch again. Anyone care to chip in?

LSE’s Naila Kabeer helped in a different way – she identified an underlying theme of the book, which I’ve been using ever since: whenever you see what looks like a fixed, monolithic institution (state, political party, legal system, NGO, corporation, social norm), you should ask yourself how is it evolving, and what is its internal make-up? Then you can try to identify potential allies in bringing about change.

LSE’s Naila Kabeer helped in a different way – she identified an underlying theme of the book, which I’ve been using ever since: whenever you see what looks like a fixed, monolithic institution (state, political party, legal system, NGO, corporation, social norm), you should ask yourself how is it evolving, and what is its internal make-up? Then you can try to identify potential allies in bringing about change.

Another enjoyable discussion was in Nijmegen (after the guitarists). Paul Hoebink asked why there is so little discussion in the book on the legitimacy of different kinds of change agents taking certain actions. His view was that membership organizations such as trade unions are inherently more  legitimate than non-membership organizations like Oxfam, but that neither is perfect. Legitimacy is an overall outcome both from accountability to different stakeholders (members in rich countries, and – for development NGOs – poor communities in developing countries) and taking part in a broad range of coalitions. I would like to read more on this – any suggestions for reading on the nature of legitimacy of non-state actors such as NGOs?

legitimate than non-membership organizations like Oxfam, but that neither is perfect. Legitimacy is an overall outcome both from accountability to different stakeholders (members in rich countries, and – for development NGOs – poor communities in developing countries) and taking part in a broad range of coalitions. I would like to read more on this – any suggestions for reading on the nature of legitimacy of non-state actors such as NGOs?

November 15, 2016

Fragility v Conflict – can you help with a new 2×2 please?

Struggling towards the finishing line on my paper on empowerment and accountability (E&A) in fragile and conflict-

affected settings (FCAS) – thanks to everyone who commented on the first draft, by the way). It’s nearly there but I need your help with one particular section.

I want to argue that lumping ‘fragile’ and ‘conflict’ together in one category is very unhelpful. In reality, many violent conflicts coexist with high levels of state capacity, while low levels of state capacity (either national or subnational) often do not generate or coexist with high levels of violence.

By conflating fragility and violence, the FCAS category muddles attempts to distinguish between E&A in different settings. That is aggravated by the use of the word ‘conflict’ to cover both contestation (omnipresent in any polity) and violent confrontation. In practice, those working on empowerment and accountability often appear inclined to interpret ‘conflict’ in its less violent manifestations, airbrushing out the horrors of war and violence. But that gives insufficient weight to issues of violence, trust and fear that profoundly change the risks and logic of working on E&A in dangerous places.

So what if we disaggregate the two in the inevitable 2×2 – does it help us think through the kinds of approach best suited to different contexts? I would really appreciate suggestions for the kinds of donor/NGO interventions that are most suited to the different quadrants, and for the countries/regions that exemplify the different categories. I’ve plonked a few in there to give you an idea, but am very unsure where things belong.

It probably needs at least one more axis – whether the state is willing or unwilling to promote empowerment and accountability (see top right quadrant), but do please have a go with these two dimensions and see what you can come up with.

I sent this to my always wise colleague Jo Rowlands and got this late night response:

‘My problem with your 2×2 , (as it usually is with them – I know they’re useful but they’re also limited as you yourself indicate in your comment about wanting a 3rd one!) is that you have to choose just one of the possible axes of fragility to juxtapose with the violence axis. Maybe what we need is an iterative 2×2 matrix, keeping the violence axis constant and cycling the other one through a range of fragility axes, in order to consider our situations through a range of lenses…otherwise, in our efforts to render something simple enough to think about, we simplify beyond usefulness.’

That sounds about right. I’m becoming a big fan of 2x2s (for example this one on aid intervention v context) because they help you look at hitherto ignored combinations and quadrants. But if they start looking like a typology, where you have to try and cram all known situations into one of four quadrants, then forget it. They should always remain an aid to thought, not a substitute for reality – a trampoline, not a straitjacket. A starting point, not the final word.

In that spirit, over to you.

November 14, 2016

Overcoming Premature Evaluation

alarming tendency to be able to reference development jargon like a machine gun. If you can get past the first para, this is well worth your time.

There is a growing interest in safe-fail experimentation, failing fast and rapid real time feedback loops. This is part of the suite of recommendations that are emerging from the Doing Development Differently crowd as well as others. It also fits with the rhetoric of ministers in Australia and the UK responsible for aid budgets about closing down failing projects and programs quickly when they are deemed to not be working.

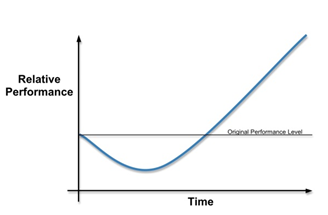

When it comes to complex setting there is a lot of merit in ‘crawling the design space’ and testing options, but I think there are also a number of concerns with this that should be getting more air time. Firstly as Michael Woolcock and others have noted it can simply take time for a program to generate positive tangible and measurable outcomes, and it maybe that on some measures a program that may ultimately be successful dips below the ‘its working’ curve on its way to that success. What some people call the ‘J curve’.

Furthermore and more importantly it ignores some key aspects of the complex adaptive systems in which programs are embedded. In the area of health policy Alan Shiell and colleagues have noted non-linear changes in complex systems are hard to measure in their early stages and simply aggregating individual observable changes fails to explore the emergent properties that those changes in combination can produce.

Furthermore and more importantly it ignores some key aspects of the complex adaptive systems in which programs are embedded. In the area of health policy Alan Shiell and colleagues have noted non-linear changes in complex systems are hard to measure in their early stages and simply aggregating individual observable changes fails to explore the emergent properties that those changes in combination can produce.

They note for example that in many areas of public health policy such as gun control that ‘multiple “advocacy episodes” may have no discernible impact on policy but then a tipping point is reached, a phase transition occurs, and new laws are introduced. In the search for cause and effect, the role played by advocates in creating the conditions for change is easily overlooked in favour of prominent and immediately prior events. To minimise the risk of premature evaluation and wrongful attribution, economists must become comfortable working with evidence of intermediate changes in either process or impact that act as preconditions for a phase transition’. Premature evaluation in cases like these could result in potentially successful programs being closed, or funding being stopped.

So how might programs be better able to measure and communicate the propensity of their programs to be able to seize opportunities (or critical junctures) if and when they might arise?

Firstly, in keeping with what a number of complexity theorists and some development practitioners have long suggested it is often changes in relationships that lie at the heart of the processes which lead to more substantive change. It is these changes in relational practice i.e. how people, organisations, states relate to each other that can eventually create new rules of the game, or institutions. However what those institutional forms will look like is an emergent property and is not predictable in advance. What is therefore required is information on changing relationships which can provide some reassurance that changes to the workings of the underlying system are occurring. An interesting example of this approach is provided by the What Works and Why (W3) project which applies systems thinking to understanding the role of peer-led programs in a public health response, and their influence in their community, policy and sector systems.

The second thing that needs to be explored are the feedback loops between the project and the system within which it is located. These are often ignored as monitoring and evaluation approaches tend to be of the ‘project-out’ variety i.e. they start with the ‘intervention’ and desperately seek directly attributable changes amongst the population groups they seek to benefit. ‘Context’ in approaches on the other handrecognise that the value of an activity or project can change over time in line with changes in the operating environment, and that multiple factors  are liable to have induced these changes. So for example a mass shooting at a school can radically change the value that a gun control program is perceived to have, which in turn can affect its ability to be successful. Enabling community organisations, local government departments, activists as well as other actors in the system to be part of this feedback is an important part of the picture. Using citizen generated data along the lines that organisations like Ushahidi promote can achieve this under the right circumstances and when politics is adequately factored in.

are liable to have induced these changes. So for example a mass shooting at a school can radically change the value that a gun control program is perceived to have, which in turn can affect its ability to be successful. Enabling community organisations, local government departments, activists as well as other actors in the system to be part of this feedback is an important part of the picture. Using citizen generated data along the lines that organisations like Ushahidi promote can achieve this under the right circumstances and when politics is adequately factored in.

The third element which needs to be recognised is that simply adding up individual project outcomes such as changes in health, income or education is not going to capture emergent properties of the system as a whole. As has been noted in India the collective ‘social effect’ of establishing quotas for getting women into local government has important multiplier effects. Repeated exposure to female leaders “changed villagers’ beliefs on female leader effectiveness and reduced their association of women with domestic activities”. Outcomes such as these need to be measured at multiple levels in different ways appropriate to the task, and factor in context rather than seek to eliminate it.

Now of course people putting up money to support progressive social change need to have some indication – during the process – that what they are supporting can, or more realistically might, become a swan, or indeed a phoenix. I argue that the following are some of things they need to be concerned about a) what is the changing nature of relationships (captured for example through imaginative social network analysis), b) whether effective learning and feedback loops are in place, c) ensuring that the demands they place encourage multi-level analysis, learning and sense-making which avoids simplistic aggregation and adding up of results.

So I am all for the move to do iterative, adaptive and experimental development, but if we are serious about going beyond saying ‘context matters’ then exhortations to ‘fail fast’ need to be more thoroughly debated.

My thanks to colleagues Alan Shiell and Penny Hawe for comments on an earlier draft.

And in a similar vein, here’s Oxfam’s Kimberly Bowman with a great post on the new Real Geek blog

November 13, 2016

Links I Liked

A polarized nation: Donald Trump won every subgroup of white voters except female college grads. He lost every  single subgroup of non-white voters. [h/t Caroline O]

single subgroup of non-white voters. [h/t Caroline O]

Saturday Night Live has had a brilliant election campaign, and finished it off in style with this moving tribute from Kate McKinnon (as Hillary Clinton), brilliantly combining a tribute to Leonard Cohen and Hillary Clinton. For great artists and more women in politics (and in comedy, for that matter) – Hallelujah.

Meanwhile, back out there in the rest of the world:

Angus Deaton and Nancy Cartwright summarize their critique of randomized controlled trials

Tensions are brewing in East Africa after low cost private schools, funded by the Gates Foundation and DFID, were ordered to close by a Ugandan court

(Lots of) academic job market advice for economics, political science, public policy, and other professional schools from the always wise Chris Blattman, including this handy guide to the differences between academic and policy research.

(Lots of) academic job market advice for economics, political science, public policy, and other professional schools from the always wise Chris Blattman, including this handy guide to the differences between academic and policy research.

DfID explains the future of its NGO funding. Useful backgrounder on DFID’s long awaited Civil Society Partnership Review to new policy

How do we evaluate adaptive management and strategic learning? Smart thinking from Kimberly Bowman on Oxfam’s new and promising ‘Real Geek’ blog

And finally thanks to Paul Ladd, Richard Cunliffe, Bianca Pereira Passaro and Ted van Hees for organizing some great launch events in Switzerland and the Netherlands last week, including this novel combo of HCH powerpoint and Kurdish Syrian/Dutch guitars

November 10, 2016

Only (re)Connect. The US elections, How Change Happens and where do we go from here?

This is just me indulging in a little personal therapy as I come to terms with this week’s political earthquake. If you want the official Oxfam response, you’ll have to wait (should be out before the 2020 elections). So this is just me. Is that clear? Good.

Oxfam response, you’ll have to wait (should be out before the 2020 elections). So this is just me. Is that clear? Good.

Trexit? Brump? 2016 is proving to be one hell of an annus horribilis for progressives (a category to which I like to think I still belong). Wednesday felt like Brexit on steroids, triggering an emotional roller-coaster akin to the grieving process:

Blank Disbelief

Gallows Humour (social media is a great comfort)

Fear, Rage & Blame (including of voters themselves for disagreeing with me and my posse)

Slowly hauling brain into gear to reengage – enquire, rethink, respond. Basically, get back on the horse – what else can we do? Give up on it all and cultivate our gardens I guess, but I hate gardening.

When the latest political earthquake happened, I was beginning three days of launch events in the Netherlands: in How Change Happens terms, here was a textbook ‘critical juncture’ – moments of drastic change in complex systems, when assumptions, power relations and possibilities are shaken up and transformed in unexpected ways (for good or ill). Unsurprisingly, the election result dominated many of my ensuing discussions. Some thoughts:

What happened? The post mortem industry is already in full swing, and I’m no pollster, but this feels very Brexit- like, a kick in the shins of business as usual/ the political elite; a populist vote against a system that has stopped delivering for a large portion of the middle class (in US terms) – the lowest income groups continued to vote Democrat (see chart); a cry of rage (laced with nostalgia) against the threat of ‘the Other’ and a perceived loss of national and cultural influence, washed away by the ubiquitous tides of globalization. Maybe even historic revenge of the rural against the complacent, patronising urban elite.

like, a kick in the shins of business as usual/ the political elite; a populist vote against a system that has stopped delivering for a large portion of the middle class (in US terms) – the lowest income groups continued to vote Democrat (see chart); a cry of rage (laced with nostalgia) against the threat of ‘the Other’ and a perceived loss of national and cultural influence, washed away by the ubiquitous tides of globalization. Maybe even historic revenge of the rural against the complacent, patronising urban elite.

That is deeply confusing for any progressive. How did the populists so adroitly steal our clothes on inequality, the evils of finance capital or unfair trade agreements? Why have ‘the people’ rejected our ideas and values so comprehensively? Why do I suddenly feel like a member of the reviled ‘elite’? As I tweeted on dazed Wednesday ‘2016= year they came w pitchforks. No-one told us they would be coming for us.’

Post Brexit, and with the real possibility of Geert Wilders winning the Dutch election next March, this upheaval/revolution is clearly a generalised phenomenon, at least within Europe and the USA. Conversations with Dutch NGO strategists saw some fairly painful self-criticism:

Why have we turned such a blind eye to regressive populism in Europe, narrowly targeting policy and spending

decisions in our campaigns, while ignoring the rising anger beyond our bubble, threatening to overturn the whole system? Is it because our project-constrained, short term approach to influencing, campaigns etc cannot tackle such deep underlying normative shifts and threats? Or we have succumbed to the creeping elitism of wanting to be ‘inside the room’, even as the room itself shrinks? Or because the centre-left has amassed too many victories that must now be protected, forcing it onto the strategic defensive (‘defend the NHS! Stop this and that!’) and meekly handing the symbolic victory of being the mould-breaker to the Right?

Why do we always gather round tangible issues (windmills, xenophobia) rather than trying to understand and directly confront the anger that underlies the backlash?

What happens next? Some possible strategies in the short term:

Be clear on red lines, where truly bad things must be confronted (persecution of migrants, minorities)

Do any opportunities lie within the populist narrative? (trade policy? finance sector reform?). But be careful – hitching your wagon to the populist locomotive carries significant risks and costs.

But the real challenge is in the long term. The progressive coalition has been asleep at the wheel, as the backlash has

gathered momentum, and ordinary people have felt increasingly angered and excluded from the benefits of the system. That requires a long term, deep rethink, and then fundamentally different response, not just a few clever  campaign videos.

campaign videos.

Shifting norms on, for example, the rights of ‘others’ is a long term exercise that we can no longer ignore. We are going to have to rebuild social cohesion from the bottom up, identifying and working with islands of social capital (faith organizations, sports, culture and the arts)

To do that we have to give up our fascinating with the corridors of power – reconnect with the people who have so clearly rejected the liberal consensus, rebuild our ability to understand and work with them.

Engaging in shifting ideas, norms and debates in the long term means transforming how we talk and communicate. Evidence isn’t enough, particularly in these post-truth times. We have to think about framing, learn to value popular narratives, tap into metaphors and popular cultural memes (the Robin Hood Tax). Not talk down to people or bombard them with statistics.

Follow that advice and I may even end up working for my son Calum, who is doing exactly this in the grassroots Citizens UK community movement. If he’d ever give me a job.

Over to you.

November 9, 2016

Campaigning for Change: Lessons of History. Top new book, free to download

I’ve blogged a couple of times on a fascinating project run by Friends of the Earth and the History and Policy  network to bring historians of past campaigns and modern day campaigners together to discuss the lessons of history. The resulting 174 page book is now out and I highly recommend it.

network to bring historians of past campaigns and modern day campaigners together to discuss the lessons of history. The resulting 174 page book is now out and I highly recommend it.

The discussion was part of FoE’s Big Ideas Change the World project (why haven’t we got one of those?). They chose 9 big campaigns from the last 200 years of UK history (they were deliberately UK centric, to ensure both familiarity  with the context among the campaigners, and a consistent context – parliamentary democracy, active civil society, strong state – to make the studies more comparable). They included some obvious candidates (abolition of slavery, women’s suffrage, Chartists) and some less obvious ones (Campaign Against the Contagious Diseases Act), including some conservative/right wing campaigns (Mary Whitehouse, left). In each case historians specializing in the campaign were asked to write a short chapter covering the campaign’s focus, ‘contention’ (narrative, framing), methods and outcomes.

with the context among the campaigners, and a consistent context – parliamentary democracy, active civil society, strong state – to make the studies more comparable). They included some obvious candidates (abolition of slavery, women’s suffrage, Chartists) and some less obvious ones (Campaign Against the Contagious Diseases Act), including some conservative/right wing campaigns (Mary Whitehouse, left). In each case historians specializing in the campaign were asked to write a short chapter covering the campaign’s focus, ‘contention’ (narrative, framing), methods and outcomes.

If you’re hoping for specific ‘lessons of history’, you’ll be disappointed – historians usually differ on the same issue and are very reluctant to draw any general conclusions. ‘We cannot use the past as a laser to point out the precise path we should follow. Rather, history is like a mirror which lets us see ourselves and understand our own time from new angles.’ More lyrically, the book ends with a quote from the Russian historian Vasily Klyuchevsky ‘History teaches us nothing, but only punishes [us] for not learning its lessons.’

In a final chapter, FoE’s Mike Childs tries to tease out 13 non-laser lessons, grouped under four ‘areas of learning’. Here they are:

Big game-plan and proxy campaigns

Look for the campaign which is the best vehicle for greater change in the future rather than deciding which campaign to run on its own merits alone. Campaigning is a multi-decadal journey. Viewing campaigning in this light may result in smarter strategies.

Avoid managerial campaigns with numerous detailed policy asks and instead focus on campaigns with a clear objective which contributes to a bigger game-plan of changing values, norms and social contexts.

Seek win-once campaigns or campaigns that are resilient to backsliding, but also be prepared for campaigning in waves, with forward momentum following by set-backs. Be prepared to use set-backs to build strength and re-invent tactics and approaches.

Approaches

The use of moral and empathy-based approaches which reaches people emotionally and touches on values may

be critical in building large and broad-based coalitions; and these will be better able to create profound change, and more powerful than rational or economic arguments alone.

be critical in building large and broad-based coalitions; and these will be better able to create profound change, and more powerful than rational or economic arguments alone.Support from within the political or economic elite facilitates effective campaigning and/or hinders the ability of an elite driven backlash, as does broader-based support from wider society. For this the use of language is critical. It is not enough to use language which motivates only existing support; it is necessary to find language that facilitates participation by the elite and wider society as well.

It is necessary to be open to a plethora of campaigns and coalitions that use widely different tactics and approaches. Homogenisation is unlikely to be successful, and certainly uncomfortable for those involved. Nonetheless a shared moral position can provide common impetus and aid cooperation and trust.

To make the status quo untenable, and in current contexts where truly mass participation activism on the scale seen in the nineteenth century does not exist, the deployment of moral arguments coupled with the use of tactical approaches such as targeting key political constituencies may be of added importance.

Tactics

Campaigns will benefit from greater and deeper engagement if they recognise the importance of strong individual and group identities through enabling people to strengthen and display their involvement, and build relationships with others who have done likewise.

People have relationships with the place they live in and the people who live there, even if this may be weakening in the age of social media. Grassroots place-based campaigning has been and will continue to be an essential element of much campaigning.

Direct action has contributed to successful campaigns in the past. Conditions such as it being a last resort, the involvement of respectable figures, and that it points to a deeper and widespread discontent are probably necessary for it to succeed.

Direct action has contributed to successful campaigns in the past. Conditions such as it being a last resort, the involvement of respectable figures, and that it points to a deeper and widespread discontent are probably necessary for it to succeed.Women have through the ages exploited and extended their sphere of influence and this has led to novel and successful tactics. For today’s campaigns looking beyond formal power relationships may also offer new approaches and tactics.

Backlash

Prepare for and understand what backlashes may emerge and from where, and prepare how to use them for the benefit of the campaign.

Recognise that the powerful cannot always control the narrative. Set out to control or change the narrative through reaching deeper values through the use of vision, frames and images.

Great to see more attention to lessons from history, and done in such a thorough manner. Kudos to FoE and H&P.

November 8, 2016

How can the international community help put women at the heart of bringing peace to South Sudan?

Oxfam’s Shaheen Chughtai reports back from a recent conversation at the UN

Once in a while, the shroud of coded, diplomatic language that envelops discussions at the United Nations Security Council is ripped away by reality. On 25th October, it was the words of a women’s rights activist from conflict-ridden South Sudan, Rita Lopidia, which gripped the chamber.

“I meet many South Sudanese women, and the stories they share with me are heartbreaking,” Lopidia told the UN Secretary General and assembled diplomats. They had gathered to review progress and challenges in promoting women’s rights and roles in conflict contexts: a theme known as Women, Peace and Security.

“A woman in Bentiu, Unity State told me recently, ‘I have been raped several times, but I still have to go out, what option do I have? I still have to find food for my children.

On a lucky day, I go out and nothing happens. On a bad day, I go out and I am raped’.”

On a lucky day, I go out and nothing happens. On a bad day, I go out and I am raped’.”

The civil war in South Sudan – where the UK is deploying 400 peacekeeping personnel – has had catastrophic impacts since it erupted in December 2013. Tens of thousands of people have been killed or injured. More than 2.6 million people are displaced, most of them women and girls. Those still inside South Sudan face increased threats of sexual assault, abduction and exploitation among other dangers.

But this isn’t a tale of victims and governments left powerless and static in the face of unstoppable atrocities. Starting from the ground up, local women and men in South Sudan are striving to bolster national and regional efforts to build peace. This is crucial because the key to ending violence and abuse is ending the war itself. To be successful, peace efforts should be based on a rigorous analysis of the causes of conflict that takes into account regional dynamics, and no-one understands those causes and dynamics better than local people and organizations.

Lopidia herself had just travelled from Nairobi where, along with South Sudanese and global partners, she convened a peace dialogue with representatives of the Transitional Government, local and global women’s groups, faith-based organizations and academia. They called on South Sudan’s leaders to rise above tribal feuding and help build a broader-based national identity and politics.

Such inclusive initiatives, in which women have an influential say, are crucial. From Liberia to Northern Ireland,

Displaced South Sudanese women walk towards the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) base in Malakal on January 12, 2014. Credit: SIMON MAINA/AFP/Getty Images

growing evidence from around the world shows that when women take an active part in peace processes, agreements are more likely to be reached and last longer. Women’s participation in South Sudan talks has been very limited to date – but this missed opportunity is something the international community, including the UK, can help change.

The UK has already taken several important and positive actions. These include contributing humanitarian aid, and strengthening its role in UNMISS, the UN peacekeeping mission in South Sudan – some of whose personnel have been implicated in cases of sexual exploitation and abuse. The UK has also been pushing for a credible peace process. But with the humanitarian situation deteriorating and peace proving elusive, more is required from the UK and its international partners.

The UK should fulfil as quickly as possible recent proposals that at least six percent of its peacekeepers deployed to South Sudan, and 15 percent of other UK personnel such as police officers, would be female. Such deployments help make UNMISS more responsive and accessible to women and girls.

More efforts are needed not just to prevent sexual violence from happening but to ensure justice and accountability when it does. This should include tougher measures to deter sexual abuse and exploitation by UN peacekeepers, as well as ensuring that victims of such crimes are recognised and justice is served – including by the special hybrid criminal court proposed by the African Union to try war crimes in South Sudan.

Women and children at the MSF hospital in Leer.

And crucially, more support is needed for local women’s rights organisations and advocates: not only in their efforts to help women and girls recover from the trauma and deprivations caused by conflict, but also in making sure that – from discussions within communities to national peace talks– women have an influential voice.

Sixteen years ago this week, the first UN Security Council resolution to specifically address the rights and roles of women and girls in conflict was adopted. Since then, the UK has become a global champion of the Women, Peace and Security agenda. At the Security Council last week, the UK’s envoy to the UN, Matthew Rycroft, urged the international community to live up to its pledges.

“Words in this Council aren’t enough,” said Rycroft. “Commitment means action every day throughout the year.”

For activists such as Rita Lopidia as well as women and girls from South Sudan to Syria, Afghanistan to Yemen, such international leadership and resolve to act remains as urgent and essential as ever.

Ends

Shaheen Chughtai co-chairs the policy working group at Gender Action on Peace and Security, based in London. Rita Lopidia is the co-founder and executive director of Eve Organisation for Women Development, an NGO in South Sudan. Both Chughtai and Lopidia represented the New York-based NGO Working Group on Women, Peace and Security at the UN Security Council’s Open Debate on Women, Peace and Security in New York on 25 October.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers