Duncan Green's Blog, page 127

January 9, 2017

What is Fiscal Justice? A rationale and some great examples

What is ‘Fiscal Justice’? It’s one of those campaign buzzwords that appears every so often, and  Oxfam is going big on it (you’ll hear plenty about it at the impending Davos meeting, provided the media cover anything other than Donald Trump’s inauguration that week). If you want to get a sense of what it means on the ground, check out Oxfam’s ‘Fiscal Justice Global Track Record’ paper, which is stuffed with case studies from 21 countries, plus the global campaign on things like tax havens that will be beating the drum in Davos.

Oxfam is going big on it (you’ll hear plenty about it at the impending Davos meeting, provided the media cover anything other than Donald Trump’s inauguration that week). If you want to get a sense of what it means on the ground, check out Oxfam’s ‘Fiscal Justice Global Track Record’ paper, which is stuffed with case studies from 21 countries, plus the global campaign on things like tax havens that will be beating the drum in Davos.

First the rationale:

‘Fiscal justice is about people having the space, voice and agency to exercise their rights, and to use this to influence and monitor fiscal systems to mobilize greater revenue and increase spending for quality public services.

Fiscal Justice is about more than technical tax or budget systems; it is about power, politics and supporting people to fight inequality. Fiscal Justice is about levelling the playing field, giving citizens a say in decision making, it is about changing power relations and tackling extreme inequality in a proactive and practical way.

Tax systems, the budget cycle and public spending are the most visible and tangible expression of the social contract between citizens and state. Increasing tax revenue allows developing countries to use and control their own resources to support their national development plans. Greater domestic resource mobilisation can improve governance and accountability, leading to fairer and more equal opportunities to access services. Fiscal justice includes revenue raising through taxation, allocation and spending on public services. It is about how tax administrations are built, how taxes are collected, how public money is spent and who benefits from that.

The budget of a country and its tax systems are not neutral – they are deeply political. The national budget is a statement of political priorities. In some countries, tax systems are biased towards consumption and wage taxes, which impact on formal sector and poorer households presenting a higher tax burden. To make tax systems fairer, tax reform is needed to shift the burden to wealthier households.

Action Aid tax campaign, Uganda

Quality Public services, like healthcare and education, can also be great equalizers, and can mitigate the worst impacts of today’s skewed wealth and income distribution by putting “virtual income” into people’s pockets. For the poorest, those on meagre salaries, this can be as much – or even more than – their actual income. Public services have the power to transform societies by enabling people to claim their rights and to hold their governments to account and to improve their life chances.’

The lessons drawn from the cross country analysis are good, but pretty generic (good FJ work needs to be context specific and engage citizens; use power analysis and multi-stakeholder approaches; timing is all). The meat is in the case studies – here’s a flavour from the Dominican Republic:

‘The Yellow Umbrella Campaign in the Dominican Republic Despite impressive economic growth, the Dominican Republic is the second most unequal country in Latin America. With a social investment level of 7.1 percent of GDP, the country lags behind the regional average of 16.2 percent. School (pre-university) education is particularly affected by investment levels which have never exceeded 2 percent of GDP despite legislation setting the minimum level of 4 percent of GDP for the education sector.

In 2012, an electoral year in Dominican Republic, an groundswell of people and civil society  organisations formed a civic movement that began to demand and mobilise around a very specific target. The target was the implementation of the General Education Law 66- 97 on budgetary matters which establishes 4 percent GDP investment in school education, which successive governments had never put into practice. Protesters, armed with yellow umbrellas – to protect themselves from the sun and the rain and with ‘4%’ printed on them in black – became the symbol of this movement.

organisations formed a civic movement that began to demand and mobilise around a very specific target. The target was the implementation of the General Education Law 66- 97 on budgetary matters which establishes 4 percent GDP investment in school education, which successive governments had never put into practice. Protesters, armed with yellow umbrellas – to protect themselves from the sun and the rain and with ‘4%’ printed on them in black – became the symbol of this movement.

Their collective action was marked by three moments: 1) aggression against a group of protesters in front of the National Palace; 2) a legal appeal presented to the Constitutional Court; and 3) a nationwide protest nicknamed “Yellow Monday”. The backlash that the protestors received far from deterring them, triggered a massive outpouring of support and social commitment via social networks, media and with public support of Dominican academics and opinion leaders. This pushed all political parties to sign the “Political and Social Commitment for Education” pledge. As a result, since 2013, the Dominican Republic government has met its legislative duty and allocated 4 percent of GDP for education.’

Smart stuff.

January 8, 2017

Links I Liked

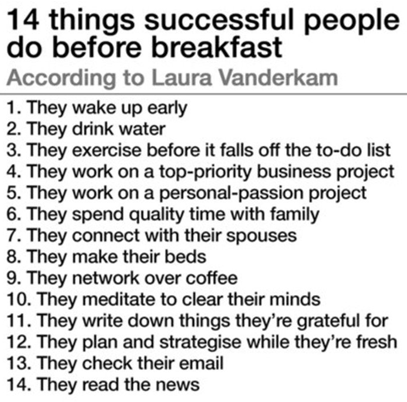

The World Economic Forum tweeted a rather silly list of ’14 things successful people do before  breakfast’. Paul Kirby reckoned ‘The secret of success must be to have breakfast in the evening’. As for trying this at home, when I try and ‘spend quality time with my family’/’connect with my spouse’ before breakfast, they turn pretty nasty…….

breakfast’. Paul Kirby reckoned ‘The secret of success must be to have breakfast in the evening’. As for trying this at home, when I try and ‘spend quality time with my family’/’connect with my spouse’ before breakfast, they turn pretty nasty…….

Lots of great commentaries on the zeitgeist – people have obviously been thinking hard over Christmas:

Hope in the dark? Brian Levy sets out a path for how activism should respond to the not-so-brave new world

Fascinating, sensible and really insightful 45 minute BBC Radio 4 exploration by Jo Fidgen on the nature of ‘post truth’. [h/t Kate Raworth]

Brilliant timing: Alex Evans’ ‘The Myth Gap: What Happens When Evidence and Arguments Aren’t Enough‘ out this week (here’s my review of the earlier online version)

‘Universal basic income is not a magic solution, but it could help millions’. And it has become more salient in light of the gig economy, automation etc

Portrait of a pandemic? How the world became obese over 40 years

I really hope DFID’s decision to cut its funding to Ethiopia’s Yegna (an NGO that uses music and radio to spread awareness about girls’ rights) was not to placate aid critics who caricatured them as ‘Ethiopia’s Spice Girls’ – it only encourages them. OK, I don’t speak Amharic, but this video suggest they are pretty great. [Update, Owen Barder says that’s exactly why they got their funding cut – depressing]

January 5, 2017

Book Review: Social Physics : How Social Networks can make us Smarter

My Christmas reading included a book called Social Physics – yep, a party animal (my others were Lord of the Flies and Knausgard Vol 3, both wonderful). Here’s the review:

Airport bookstores are bewildering places – shelf after shelf of management gurus offering distilled lessons on leadership, change and everything else. How to distinguish snake oil from substance? My Christmas reading, based on a recommendation from someone attending a book launch in the US last month (thanks whoever you were – all a bit of a blur now) was Alex Pentland’s ‘Social Physics: How Social Networks can make us Smarter’. I must confess, as a lapsed physicist, the title swung it for me, but I learned a lot from this book. At least I think I did – let’s see if I am still using the ideas in a few months’ time.

lessons on leadership, change and everything else. How to distinguish snake oil from substance? My Christmas reading, based on a recommendation from someone attending a book launch in the US last month (thanks whoever you were – all a bit of a blur now) was Alex Pentland’s ‘Social Physics: How Social Networks can make us Smarter’. I must confess, as a lapsed physicist, the title swung it for me, but I learned a lot from this book. At least I think I did – let’s see if I am still using the ideas in a few months’ time.

Social Physics is not a new idea. Auguste Comte, the founder of modern sociology, coined the phrase back in the 19th century. Comte and his crew aspired to explain social reality by developing a set of universal laws—the sociological equivalent of physicists’ quest to create a theory of everything. As with economics, that kind of physics envy has proved largely delusional. Now though, Pentland argues that the arrival of Big Data means we can aspire to a ‘thermodynamics of society’, where behaviour is governed by discernible mathematical laws. It does not deny free will – Pentland does not claim to be able to predict individual behaviour, but finds a high degree of certainty in mass behaviours, which appear to follow particular patterns (like atoms in a gas).

Big Data allows us to move from describing society in terms of stocks (equilibria, population, education and health status) to real time flows (of information, ideas, contacts) and this transforms are ability both to understand and accelerate human progress.

The two most important concepts in SP are

Idea flow within social networks, and how it can be separated into exploration (finding new ideas/strategies) and engagement (getting everyone to coordinate their behaviour)

Social learning, which is how new ideas become habits, and how learning can be accelerated and shaped by social pressure

Lots of data

Compared to other gurus with similar messages about the need to move beyond assumptions about ‘rational, utility-maximising individuals’, Social Physics has more emphasis on social interaction and collective rationality than Kahneman or Nudge.

Pentland sees the flow of interaction and ideas in social physics as ‘a language that is better than the old vocabulary of markets and classes, capital and production’. The tone is ambitious: ‘we can begin to build a society that is better at avoiding market crashes, ethnic and religious violence, political stalemates, widespread corruption, and dangerous concentrations of power.’ Sign me up.

The later sections of the book on how to redesign cities (we need to be more like Zurich, apparently) and rethink politics and governance for an era of Big Data were a bit underwhelming – what got to me were the earlier sections on individuals and organizations. And I found some of it quite uncomfortable.

According to Pentland, creativity is born of two processes: the first is exploration, where people move out of their comfort zones and actively seek people with different views and ideas. He also stresses the importance of curmudgeons and contrarians who argue against the conventional wisdom of the day. Great, that’s what I spend a lot of my time doing – reading books like this for example, or talking to academics and businesspeople as well as activists, or pouring scorn on the latest fads and fashions when they annoy me.

The second process is engagement, which proved a lot less reassuring when I think about how I behave in meetings. ‘Groups have a collective intelligence that is mostly independent of the intelligence of individual participants’. The most creative and effective processes of engagement are those that show ‘equality of conversational turn taking’ – discussions in which no-one dominates, lots of short idea-and-response type exchanges. The key finding is that the dynamics of the exchange are more important than the knowledge and experience of the individual participants. The exception is ‘social intelligence’ – the ability to read other’s social signals, in which (surprise surprise) women have a distinct advantage.

So what are the practical implications? Well, one of Pentland’s numerous spin-off companies can

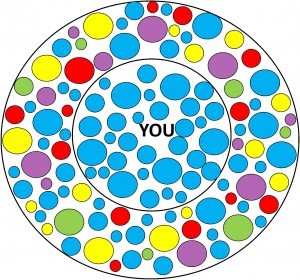

Which one’s me?

rig you up with an app to monitor meeting dynamics: a visual display on your phone shows who is hogging the airtime – particularly useful when some participants are not in the room (eg conference calls) or speaking a second language). In another case they persuaded a company to make its lunch tables longer, so people chatted beyond their core peer group. Coffee pots and water coolers (hell, maybe even Open Plan) turn out to be essential. More generally, you can think about the balance of exploration and engagement (one of my many unheeded suggestions in Oxfam is that everyone should have a read-out of the percentage of their monthly emails that comes from non-Oxfam sources). That balance needs to be at both an individual level (everyone probably needs to get out more and ‘oscillate’ between exploration and engagement, even if it’s just having a coffee with people from elsewhere in the organization) and collective level (how is our balance of explorers and engagers?) Some activist organizations have a monthly target for one-to-ones with grassroots leaders – maybe aid agencies should do something similar?

These are not terribly original insights, but Pentland’s argument is that Big Data allows you to precisely measure and optimise an organization’s performance, ‘tuning’ its combination of exploration and engagement. As proof of the pudding, his spin-offs have done this for a number of companies and others with (he says) good results. I’m torn by this – sceptical that you can apply such quantitative methods to something as human as an organization, but also attracted by the focus on systems and interactions, and the lure of promised precision.

Any other caveats or qualms? A couple. Even by my narcissistic standards, the book is remorselessly first person: ‘I’ is probably its commonest word – Pentland, who is a prof at MIT, does not suffer from false modesty and locates himself at the heart of pretty much every important idea or development in the field. Then there’s ‘we’, as in ‘we can build better social systems’. Who, pray, is ‘we’? Who gets to decide who can join? What motivates the ‘we’? – the pure altruism of the disinterested datacrat, or something much more complicated? He seems remarkably un-self-aware in all this.

Which, you won’t be surprised to hear, makes me wonder about power and politics. Sure, Pentland has some quintessentially American ideas of curbing state excess through a ‘New Deal on Data’ that combines safeguards with the benefits of openness, but otherwise, this is a datacrat’s dream, with philosopher kings wielding algorithms and apps for the benefit of the common weal. Published in 2014, I wonder whether he would change much in the era of post-truth politics?

And here’s Pentland introducing his ideas (50m, he starts at 2.12)

January 4, 2017

How bad is my filter bubble problem? Please help me find out

In an idle moment over the Christmas break, I decided to run a twitter poll to assess the extent of  my filter bubble. For any of you who’ve been on a different planet for the last few months, that’s the social media phenomenon whereby you like/follow/read only those sources that broadly agree with you, creating an echo chamber that can lead to you mistakenly thinking that the public agrees with you. I realized how bad things were when I noticed that even the things I read that are furthest from my own general views, e.g. the Economist, were in the same Clinton/Remain camp as me.

my filter bubble. For any of you who’ve been on a different planet for the last few months, that’s the social media phenomenon whereby you like/follow/read only those sources that broadly agree with you, creating an echo chamber that can lead to you mistakenly thinking that the public agrees with you. I realized how bad things were when I noticed that even the things I read that are furthest from my own general views, e.g. the Economist, were in the same Clinton/Remain camp as me.

So I used the handy new twitter polling tool to ask my twitter followers to say which combination of Trump/Clinton and Brexit/Remain they voted for or supported (where not eligible to vote). As I’d expected, the initial responses were heavily Clinton/Remain (94% after 150 votes), then fell back a bit as people retweeted and so more diverse networks came into play. Even so, after 24 hours and nearly 400 votes, it was still 90%. Final results were:

3% Trump and Brexit

2% Trump and Remain

5% Clinton and Brexit

90% Clinton and Remain

Lots of walls, not many bridges

Charles Kenny sensibly pointed out that this was measuring the wrong people – the followers rather than the followed, which is where I get my information and ideas from. Anyone got an idea for how to assess the uniformity/diversity of the latter (other than some massive exercise in analysing all their tweets)?

But it was still an interesting exercise – gave me a sense of two big in/out networks with very few bridges between them. So I thought I’d run it as a poll on the blog (with other options acknowledged this time – apologies to the people in the US who voted for 3rd party candidates – forgot to offer that option on the twitter poll). Over to you.

Note: There is a poll embedded within this post, please visit the site to participate in this post's poll.

What to do about it? I can’t see me avidly consuming the Daily Mail every morning, but does anyone know of a curated source of articulate, intelligent opinion from outside my bubble? If not, could someone please start one?!

Matt Collin weighed in on twitter with a few thoughts:

Start up dialogues with groups you never talk to (e.g. anti-aid, Brexitiers)….

Do talks in communities in ‘Little England’, connecting development issues to local ones

Pitch pieces for conservative newspapers/sites, even if rejection rate is v. high. Write about issues that build bridges between sides

All good ideas, but all difficult to do in practice – I generally wait to be invited to speak, and suspect I will have to wait a long time for an invitation from the anti-aid lobby, except as a human sacrifice (tried that, not fun). Hours in the day a problem on endlessly pitching to conservative media.

On the other hand, I don’t think I have the chutzpah (or, let’s be honest, the looks) to do what Arab-American tenor Karim Sulayman did shortly after the US election

Karim Sulayman – I trust you from Meredith Kaufman Younger on Vimeo.

Any other suggestions for effective, time efficient ways to break through the bubble?

January 3, 2017

Links I Liked

A few links from either side of the Christmas break, to provide some initial distractions in 2017

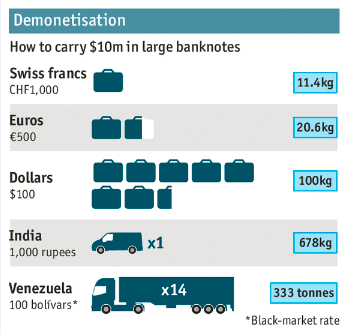

How much does $10m in large banknotes weigh? Carrying bags of cash is (luckily) easier on the

back in Davos than Caracas (h/t The Economist)

Great (long read) interview with inequality guru Branko Milanovic

The focus on better communicating certain ‘truths’ is misplaced: academics must improve their emotional literacy

Apply now for the new LSE’s new Atlantic Fellowships in Economic and Social Inequalities

Let’s bring the mood down. Last year Bloomberg envisaged President Trump and Brexit. Now here’s their pessimist’s guide to 2017

And up again. ‘My Big Idea For 2017: Time To Build The Human Economy’, bit of much-needed inspiration from Winnie Byanyima

Are Women Really Happier than Men Around the World? Interesting attempt to answer a really difficult question

This might be the coolest visualization of evolution ever (and a very scary depiction of antibiotic resistance)

January 2, 2017

How many readers? Where from? What were their favourite posts? Stats for 2016 on FP2P

Hi everyone, Happy New Year and all that. Thought I’d kick off with the usual feedback post on last year’s blog stats:

The blog passed a couple of milestones last year – since it started in 2008, it’s clocked up 2000 posts, 1.4 million words, and 10,000 comments (big thanks to everyone who takes the time to add  theirs). Only a matter of time before the blog accidentally reproduces Hamlet (monkeys, typewriters ….)

theirs). Only a matter of time before the blog accidentally reproduces Hamlet (monkeys, typewriters ….)

Overall reader stats for 2016 were:

319,607 ‘unique visitors’ – not quite the same as ‘different readers’, as if you read the blog on your PC, laptop and mobile, that counts as 3 people. Within the year, the usual trend – a weekly cycle of low weekend reads, and summer and Christmas lulls (see graph). Those numbers are pretty much  identical to 2015, which I’m happy with as I took a blog break when I was finishing the book in Jan/Feb, so only 214 posts in 2016, compared to 242 the previous year (equal to a 13% increase in hits per post).

identical to 2015, which I’m happy with as I took a blog break when I was finishing the book in Jan/Feb, so only 214 posts in 2016, compared to 242 the previous year (equal to a 13% increase in hits per post).

Most-read Posts: these continue to surprise me – only two of the top 10 were new – who says blogging is ephemeral? Apart from a possible bias towards aid industry related topics, I can see very little pattern behind this list – polemics, geek-food, how-to guides and just plain random stuff – could someone please tell me why a 2009 post on climate change in South Africa is still getting 10,000 hits a year?

How is climate change affecting South Africa? (a 2009 post – the oldest in the list).

How much should Charity Bosses be paid? (from 2013)

How to get a PhD in a year and still do the day job (from 2011)

Religion and Development: what are the links? Why should we care? (from 2011, but weirdly, a new entrant to the list)

Are women really 70% of the world’s poor? How do we know? (2010, also a new entrant)

What are the limitations to a human rights based approach to development? (2014)

The 2016 Multidimensional Poverty Index was launched yesterday. What does it say? (the highest ranking post from 2016)

How does emigration affect countries-of-origin? Paul Collier kicks off a debate on migration (2014 post, appearing for first time – that has to be Brexit!)

How do developing country decision makers rate aid donors? (2016)

How to write a really good executive summary (2014 post)

Neither of the all time top FP2P posts made it this year – What Brits say v what they mean and The world’s top 100 economies: 53 countries, 34 cities and 13 corporations.

Where were the readers from? Same top 10 to last year, with South Africa moving up the rankings (probably that climate change post, again).

71% of readers used PCs and only 23% read it on their mobiles (5% used tablets). Does that mean the blog’s not very mobile-friendly?

If you can see any other patterns or useful lessons do let me know, and I always appreciate suggestions for improving the blog. It’s about time I ran a reader survey (last one was about five years ago) and had another think about addressing some of the enduring challenges/weaknesses of the blog – eg more debates, getting more posts from Southern authors. Watch this space.

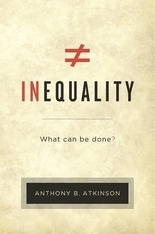

RIP Tony Atkinson: Here he is on our personal responsibility for reducing inequality

Tony Atkinson, one of the world’s great thought leaders on poverty and inequality, died on New Year’s Day. C ombining intellectual rigour and a profound commitment to social justice, his life’s work epitomised the economics profession at its best. Here he is in the final chapter of his 2015 book ‘Inequality: What can be done?’

ombining intellectual rigour and a profound commitment to social justice, his life’s work epitomised the economics profession at its best. Here he is in the final chapter of his 2015 book ‘Inequality: What can be done?’

‘I do not accept that rising inequality is inevitable: it is not solely the product of forces beyond our control. There are steps that can be taken by government, acting individually or collectively, by firms, by trade unions and consumer organizations, and by us as individuals…..

It is individuals who will ultimately determine whether the proposals set out here are implemented and whether the ideas are pursued. They will do so indirectly in their capacity as voters, and – perhaps today more importantly – as lobbyists through campaign groups and social media, acting as countervailing power to the paid members of the lobbying profession. Sending that email message to your elected representative makes a difference. But individuals can influence the extent of inequality in our society directly by their own actions as consumers, as savers, as investors, as workers, or as employers. This is most evident in terms of individual philanthropy. Where transfers of resources not only are valuable in themselves but also provide a powerful signal of what we should like to see done by our governments.

But transfers are only part of the story. Consumers make a difference by buying from suppliers who are paying a living wage, or whose products are fairtrade. Individuals, acting on their own or collectively, make a difference by supporting local shops and enterprises. Savers can ask about he salary policy pursued by their shareholder-owned bank; they can transfer their funds to a mutual organization. Market forces may limit the range of outcomes, but they leave room for other concerns to come into play, such as fairness and a sense of social justice, ethical decisions, and – taken together – our decisions can make a contribution to reducing the extent of inequality.

But transfers are only part of the story. Consumers make a difference by buying from suppliers who are paying a living wage, or whose products are fairtrade. Individuals, acting on their own or collectively, make a difference by supporting local shops and enterprises. Savers can ask about he salary policy pursued by their shareholder-owned bank; they can transfer their funds to a mutual organization. Market forces may limit the range of outcomes, but they leave room for other concerns to come into play, such as fairness and a sense of social justice, ethical decisions, and – taken together – our decisions can make a contribution to reducing the extent of inequality.

If we are willing to use today’s greater wealth to address these challenges, and accept that resources should be shared less unequally, there are indeed grounds for optimism.’

And here’s the FT’s excellent obituary

December 20, 2016

Is this time really different? Will Automation kill off development?

Is this time really different? That’s the argument whenever people want to ignore the lessons of  history (eg arguing that this particular financial bubble/commodity boom will never burst) and such claims usually merit a bucketload of scepticism. On the other hand (climate change, nuclear war) sometimes things really are different from everything that has gone before.

history (eg arguing that this particular financial bubble/commodity boom will never burst) and such claims usually merit a bucketload of scepticism. On the other hand (climate change, nuclear war) sometimes things really are different from everything that has gone before.

Which brings us to technology. Lots of musings are circulating about the rise of Artificial Intelligence, automation etc. Driverless cars will put millions of drivers out of work. Robots will kill off manufacturing jobs. Everything will change.

At the World Economic Forum, Klaus Schwab talks of ‘the fourth industrial revolution’. The bible is the Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies, a 2014 book by Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee. Even President Obama has caught the bug, in a recent profile in the New Yorker

‘At some point, when the problem is not just Uber but driverless Uber, when radiologists are losing their jobs to A.I., then we’re going to have to figure out how do we maintain a cohesive society and a cohesive democracy in which productivity and wealth generation are not automatically linked to how many hours you put in, where the links between production and distribution are broken.’

Which all raises a whole series of questions – is it true? If so, is that a Good/Bad Thing and for whom? Much too substantial for a blog post, but here are a few thoughts and links.

Which all raises a whole series of questions – is it true? If so, is that a Good/Bad Thing and for whom? Much too substantial for a blog post, but here are a few thoughts and links.

Is it true? Ever since the Luddites, the machines have been about to take our jobs (see this 200 year timeline, c/o Ranil Dissayanake). Techno-optimists argue that the current concerns are just another loss of collective nerve – new jobs will emerge to fill the gaps created by technology. But beyond the lessons of history, I see no reason why this should inevitably be true, at least not with the wages and conditions people have become used to (or aspire to). The scale and pace of the changes described above do suggest this time may really be different – a lot of disruption and job displacement could take place, at a time when governments seem less willing/able to help people adjust and cope.

Is that a good thing or bad thing? If the jobs being lost are menial or demeaning, shouldn’t we join those who are celebrating? Couldn’t this be the start of a brave new world where everyone works for 12 hours a week and then enjoys their leisure? (After all, that was what we were being promised back in the 1970s – back in 1930 if you read Keynes – yet somehow it never arrived.) For automation to usher in an age of positive leisure, an awful lot of public action needs to take place – states need to educate their people, those people need to organize to ensure that the benefits of automation are fairly distributed.

Because the alternative is rising inequality, captured in the Obama quote. At the extreme, something akin to HG Wells ‘The Time Machine’ and numerous other scifi dystopias – a privileged techno elite ruling over a mass of surplus-to-requirement proles whose main role is as threat to elite power.

And what does all this have to do with development? A lot of the aid business doesn’t seem to have  noticed these debates. It bangs away about the need for Industrial Policy and decent formal sector (preferably manufacturing) jobs – an essentially Fordist/Post World War Two agenda.

noticed these debates. It bangs away about the need for Industrial Policy and decent formal sector (preferably manufacturing) jobs – an essentially Fordist/Post World War Two agenda.

But there are a few interesting discussions. The ODI has started a fascinating piece of work on the implications of the gig economy for domestic workers in developing countries. Dani Rodrik argues that this is part of a wider story of ‘premature de-Industrialization’, and worries that the historic engine of development is running out of steam. IIED’s Andy Norton argues that green growth could be the answer to Rodrik’s dilemma. UNRISD has been gamely plugging away at researching one potential alternative – the ‘social and solidarity economy’.

Automation’s separation of paid labour from human wellbeing is also one argument for a Universal Basic Income, especially if paid for by taxing global public bads like carbon emissions. The UBI becomes the starting point, and the rest of the economy is laid on top of that. Would that address poverty? Possibly in the narrow income definition but not if we extend the definition to power, access and other dimensions. It certainly wouldn’t address exclusion, or discrimination, violence,

Time Machine, with Keith Richards lookalike

insecurity etc. If the UBI is only about rights to cash but no responsibilities, then we have something to learn from those who have been raised in a handout economy. Indigenous Australians called the dole ‘sit down money’ and hence developed the Community Development Employment Programme (basically welfare payments in recognition of what people contribute to the community, outside the formal market economy – eg caring for country, preserving traditions, etc).

What worries me more generally is the lack of politics. Lots of big picture, visionary, ‘If I ruled the world’ solutions, but what are the political conditions for bringing them about? The underlying story of the struggles of European Social Democracy is the decline of organized labour – and automation will further weaken that historical foundation for progressive ideas and policies. Attempts to rebuild progressive coalitions based on a ‘rainbow’ of different marginalized groups have had limited success to date. The danger is that, without a strong and coherent political voice, the future will be more HG Wells than UBI-supported leisured masses frolicking in the meadows.

Wow, I definitely need that Christmas break, but wd be interested in your thoughts!

Back in January, hopefully rested, optimistic and more coherent (I can always dream, right?)

Thanks to Irene Guijt, Katherine Trebeck and Paul O’Brien for comments on earlier drafts

December 19, 2016

‘Odd but Interesting’: Clare Short reviews How Change Happens

Clare Short was DFID’s first minister (1997-2003) and a force of nature (for example she was one of the originators of what became the Millennium Development Goals). Great when she agreed with you, pretty brutal when she didn’t. Which in the case of NGOs, was quite a lot of the time – she had the traditional Labour Left dislike of middle class, self-appointed, self-righteous dogoodery (a grotesque caricature of us activist types, I hope you realize….). So I reckon I get off lightly from her thoughtful review (paywalled) in The Tablet (the magazine for the Catholic intelligentsia):

when she agreed with you, pretty brutal when she didn’t. Which in the case of NGOs, was quite a lot of the time – she had the traditional Labour Left dislike of middle class, self-appointed, self-righteous dogoodery (a grotesque caricature of us activist types, I hope you realize….). So I reckon I get off lightly from her thoughtful review (paywalled) in The Tablet (the magazine for the Catholic intelligentsia):

‘An odd but interesting book. Duncan Green, who has worked for development organisations for 35 years, aims to explain how change happens so that activists might be more effective in achieving their objectives. The activists are not defined precisely; Green seems largely to have in mind those in development agencies who campaign for change across the world. There is a general assumption that what they wish for are uncomplicatedly good things; there is no discussion of where their legitimacy comes from.

There is a lot of arrogance in development agencies. They are full of people of good intent who are too easily convinced of their own righteousness. It would do them good to read How Change Happens. It calls for a change from seeing international development as like baking a cake with a clear recipe and a clear outcome to being more like bringing up a child. Green stresses that systems are complex and are constantly changing. Activists need to have more humility, to study the history of the institutions they are trying to change and to be more conscious of their own prejudices and power.

Green gently remonstrates with some of his colleagues in the development world. He clearly fears that many of them reject the way of thinking he’s advocating. They worry instead about “analysis paralysis” and prefer to take action without reflection. Green believes that the problem of rushing in too quickly to solve a problem is accentuated by donors who demand easily measurable results in a short timescale. He’s right – the bureaucratic demands in the current international development system stymie creativity, flexibility and effectiveness.

Green makes an interesting categorisation of different kinds of power – there is power within ourselves, power with others for collective action, power to decide what action to take and, finally, power that gives domination over others. And again he cautions that many non-governmental organisations and faith organisations over-invest in individual empowerment and fail to support collective action to take on oppressive power because they are leery of “politics”. Studying where power lies, he concludes, is crucial to effect change.

Green makes an interesting categorisation of different kinds of power – there is power within ourselves, power with others for collective action, power to decide what action to take and, finally, power that gives domination over others. And again he cautions that many non-governmental organisations and faith organisations over-invest in individual empowerment and fail to support collective action to take on oppressive power because they are leery of “politics”. Studying where power lies, he concludes, is crucial to effect change.

Green gives examples of successful change-making and examines why the Paris talks on climate change in December 2015 were successful, while the Copenhagen meeting in 2009 had been such a spectacular failure. He was of course writing before the election of Donald Trump threatened the progress achieved in Paris.

Perhaps surprisingly, but I think rightly, Green is pragmatic about how states evolve and reform, and takes a sober and realistic view of the possibilities of working with multinational companies. He begs forgiveness from his more anti-capitalist colleagues, but he is honest enough to report that his time with the Ethical Trading Initiative has given him a lasting respect for the dynamism and seriousness of some of the people who run transnational companies.

This book is hugely ambitious. It attempts to explain how change can be driven in all parts of the international system. Although its lessons are drawn from the world of development activism, they are applied more broadly. Senior figures in the development world lavish fulsome praise on Green’s analysis. I’m not sure that it is quite as seminal as they suggest, but I was struck by this quote from Milton Friedman that he includes: “Only a crisis – actual or perceived – produces real change. When a crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around. That, I believe, is our basic function: to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes politically inevitable.”

This is of course exactly what happened in the 1980s, when Keynesianism was sidelined, the market became king and inequality was allowed to rip. Maybe now is a good time to read How Change Happens, to reflect on how we got to the state we are in and to prepare some alternative ideas, so that when the next crisis comes we will be able to use them to build a more generous and equitable future.’

December 18, 2016

Links I Liked

When scientists protest, their placards have footnotes [h/t Bill McKibben]

Are economists partly responsible for the rise of populism? Dani Rodrik argues that by abandoning evidence to become cheer leaders for globalization, they helped contribute to the backlash

The Digital Divide is serious: Fewer than half of all Africans have phones; 3/4 don’t use the internet. Here’s one reason why that matters. From 2008-14, 2% of  Kenyans were lifted out of poverty by MPESA mobile banking, according a to new study vox.com/world/2016/12/…

Kenyans were lifted out of poverty by MPESA mobile banking, according a to new study vox.com/world/2016/12/…

A Year of Big Ideas in Social Change. Interesting, challenging (if apolitical) from Tina Rosenberg of NY Times on what corporates can teach activists

Harvard tops the latest global university rankings for development studies, followed by Sussex & LSE. Cool – 3 of my favourite places

Talking of which, here’s the Harvard Business Review with a sensible introduction to the strengths and weaknesses of Solving Social Problems with Machine Learning

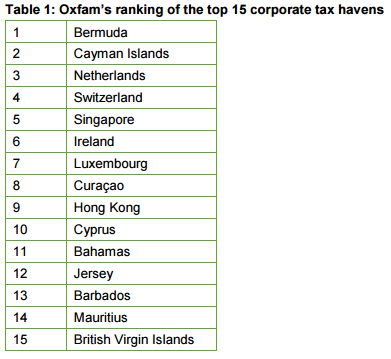

World’s worst tax havens, from ‘Tax Battle’, a new Oxfam report on the global race to the bottom on corporate tax

Making America Grate Again? Pres Elect Trump’s 17 cabinet-level picks have more money than a third of American households combined

The EU made an awful propaganda video about how it has responded to refugees, so MSF fixed it for them in a nice update of the old adbusting style [h/t Ben Phillips, plus Bill Sims and Annie Feighery for tech advice!]

So @EUCouncil made an awful propaganda video on refugees. @MSF_sea took it and added a dose of reality… Brilliantly done. pic.twitter.com/VNIQI3xaRp

— Andrew Stroehlein (@astroehlein) December 15, 2016

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers