Duncan Green's Blog, page 129

December 5, 2016

Power, Poverty and Inequality: a ‘love-peeve’ new IDS bulletin

I have something of a love-hate relationship with the Institute of Development Studies (IDS) in Brighton, or more accurately, a love-peeve. I love the topics, the commitment to bottom-up approaches, and the intellectual leadership IDS has shown over the years on a whole range of issues dear to my heart. The peeve stems from its preference for abstruse language and reluctance to commit to the ever-elusive ‘so whats?’ Apart from the ubiquitous ‘needs more research’ conclusion of course – funny that.

Studies (IDS) in Brighton, or more accurately, a love-peeve. I love the topics, the commitment to bottom-up approaches, and the intellectual leadership IDS has shown over the years on a whole range of issues dear to my heart. The peeve stems from its preference for abstruse language and reluctance to commit to the ever-elusive ‘so whats?’ Apart from the ubiquitous ‘needs more research’ conclusion of course – funny that.

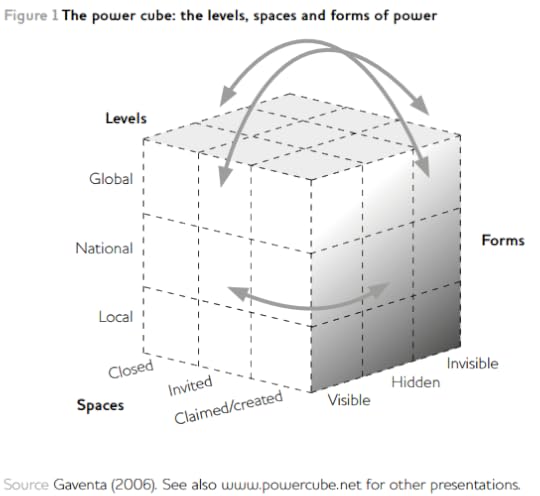

Those mixed emotions were in full flow as I read the new IDS Bulletin on Power, Poverty and Inequality, which is now Open Access (see, aren’t they great? You paying attention, ODI?) The bulletin takes stock of the discussion on power, ten years after John Gaventa came up with the Power Cube as a handy way of bringing together different kinds of power into a single analytical framework (see diagram below). The focus of the bulletin is on ‘invisible power’:

Invisible power involves the internalised, often unconscious acceptance of dominant norms, institutions, languages and behaviours as natural and normal, often desirable, even if they appear to be against the interests of the actors involved. Acceptance helps to perpetuate an unjust status quo. This aspect of power helps explain how certain matters are, for long periods of time and in many places, not on the agenda for discussion and unchanged, because they are naturalised: unnoticed and satisfactory – the internalized understandings in people’s heads of their place in the world of norms and ‘the natural’.

The overall conclusion is classic IDS: ‘change is accelerated when connected spaces at every political level are considered and economic, political and social cleavages are acted on in concert.’ Okaaayyy.

What that seems to involve is a serious effort to render invisible power visible to those who it is keeping down, when it is ‘brought into the light and becomes available for change’. Making invisible power explicit allows it to be acknowledged, questioned and ‘denaturalised’.

At which point I rub my hands and say ‘great, show me how to do it, let’s see some practical examples and recommendations for activists’. But this is IDS, it’s never that easy, and never quite lands, preferring to do pirouettes in the meta world of academia than get down and dirty with grubby activists. Even the case studies, of which there are several (on access to water, or social exclusion in the Balkans), seem somehow trapped in IDS-world and never quite land. Then we’re back in the comfort zones of ‘intersectionality’ and ‘towards a pedagogy for the powerful’.

At which point I rub my hands and say ‘great, show me how to do it, let’s see some practical examples and recommendations for activists’. But this is IDS, it’s never that easy, and never quite lands, preferring to do pirouettes in the meta world of academia than get down and dirty with grubby activists. Even the case studies, of which there are several (on access to water, or social exclusion in the Balkans), seem somehow trapped in IDS-world and never quite land. Then we’re back in the comfort zones of ‘intersectionality’ and ‘towards a pedagogy for the powerful’.

Am I being unfair/reductionist? Probably – I read the bulletin on a plane journey and doubtless missed stuff (if so, IDS colleagues please set me straight). And there are some more satisfying bits in the articles from Jethro

Guatemalan indigenous protesters

Pettit and my Oxfam colleague Jo Rowlands . Jethro Pettit looks at the reasons why citizens don’t engage, and the role of invisible power in making people accept their subordination as the way things are. He has a nice (albeit very IDS-ish) paragraph on the role of culture:

Creative methods can evoke more felt and experiential knowledge of the past and deeper re-imaginings of possible futures. Movement and theatre can surface and interrogate embodied experience, and engage participants in reinventing their habituated and physiological responses to power. Drawing, painting, photography, film and sculpture all offer powerfully visceral and aesthetic avenues of learning that can both enhance and transcend more conceptual and analytical methods of sense-making. This is not a new proposal, but one that is sadly overlooked. Creative and narrative methods have been widely advocated in transformative approaches to participatory and action research. Social movements have long drawn on forms of popular education and cultural expression using ‘songs, poetry and theatre’ and ‘especially local cultural forms to give voice, pass on history and engender solidarity’. Cultural action of this kind enables more than just symbolic and conceptual expressions of identity and struggle: it invites the possibility of more affective and embodied re-imaginations of power and social order.

These creative and embodied forms of learning provide different ways of generalising from the particular than those offered by conceptual analysis. They can hold open our lived experience of power to more immediate forms of apprehension, without jumping too quickly into abstract thinking, or allowing symbolic representations to substitute for embodied understanding and knowledge. This approach doesn’t reject the power of the intellect and critical consciousness, but brings them into balance with other ways of knowing.

These creative and embodied forms of learning provide different ways of generalising from the particular than those offered by conceptual analysis. They can hold open our lived experience of power to more immediate forms of apprehension, without jumping too quickly into abstract thinking, or allowing symbolic representations to substitute for embodied understanding and knowledge. This approach doesn’t reject the power of the intellect and critical consciousness, but brings them into balance with other ways of knowing.

For her part, Jo offers a guardedly optimistic take on Oxfam’s embrace of power analysis over the last ten years (something for which she has been a tireless advocate). She identifies five obstacles to this effort:

Content: ‘The language of power analysis can be quite obscure and/ or unnecessarily academic.’ (who could she be referring to?). ‘It is important to communicate that although power is multifaceted, it is in no way mysterious and can be explored and made sense of. Power is around us everywhere, we all experience it in multiple ways even if we never think about it.’

Skills: ‘Some people seem to have the knack of power analysis without even thinking about it much. Such people read the context, connect with diverse sources of information and seem almost intuitively able to keep a finger on a multifaceted pulse in terms of the political context. Such people are not commonly found in development management, though sometimes they are found in policy roles.’ As a result they ‘bring in experts’, which is usually a bad idea, as the organization fails to internalise power analysis.

Responsibility and Accountability: ‘In an organisation like Oxfam, power analysis is one of those areas that usually falls across several areas of responsibility and is therefore vulnerable to having no one actually accountable for ensuring it happens.’

Application: ‘Power analysis is most usefully iterative and ongoing, used to identify priorities, partnerships and alliances, to guide a range of relationships, to inform linkages between work at different levels. So it needs to be built into planning cycles, adequately resourced and monitored.’

Time: Heavy workloads, competing priorities, multiple deadlines and very ambitious programmes mean that it can be hard to carve out space for analysis and reflection. Space for learning, often closely linked with monitoring and evaluation, is increasingly being built into programme plans, and power analysis lends itself easily to these spaces.’

Maybe IDS could consider a follow up bulletin which takes overcoming Jo’s five obstacles as its starting point and sticks resolutely to plain English?

December 4, 2016

Links I Liked

Despite being on the road in US flogging books, a couple of things caught my bleary jet-lagged eye.

Delighted that How Change Happens makes it to the top of ‘Thoughtful Campaigner’s’ Xmas book recommendations for development wonks. Whole list is worth a look.

Lots of stuff on aid

Characteristically contrarian MSF critique of the localization agenda in humanitarian response. Does ‘Political correctness’ gloss over the political minefields?

The UK aid watchdog says its private sector arm, CDC, is not showing evidence of impact, yet DFID has just quadrupled its budget ceiling. Is this ideology trumping a commitment to results?

Podcast highlights of a recent Radio 4 panel discussion on the future of the UK aid with Owen Barder, Kirsty MacNeill, Andrew Mitchell and some other bloke

And Fidel died. This 6 minute obit from Channel 4 news seemed fairer than most. Plus a superb Branko Milanovic reflection on Castro’s death and the ending of a century of ‘the first global secular religion’ – Communism

This brilliant infographic on cash transfer myths from UNICEF repays close study

December 1, 2016

Doing Data Differently: Lessons from the Results Data Initiative

Guest post from Dustin Homer, Director of Engagement and Partnerships at Development Gateway

Development folks see magical possibilities for data-driven decision-making. We want data and evidence to improve our work—to help us reach marginalized people, allocate budgets effectively, and see which activities work the best. And it’s not all buzz; we’re getting serious about investing real resources into this development data revolution.

So here’s the question: if we’re serious about promoting data-drive decisions, what should we actually invest in? Or more specifically, how do you help someone else use data more meaningfully [or can you]?

Local governments and organizations serve people directly, so we think it’s critical to focus on the ‘data revolution’  from their perspective first. With support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, we asked some 450 people in Ghana, Sri Lanka, and Tanzania to tell us how they use health- and agriculture-focused results data and what they’d like to do differently. We’ve distilled a few lessons that are important for the wider data-for-development community:

from their perspective first. With support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, we asked some 450 people in Ghana, Sri Lanka, and Tanzania to tell us how they use health- and agriculture-focused results data and what they’d like to do differently. We’ve distilled a few lessons that are important for the wider data-for-development community:

Getting the right data: When we talk about local-level data, we aren’t talking about much. Of course our community knows this well—we talk about needing more data, higher-quality data, and better-disaggregated data. This is all true. But the bigger point is that the data that local actors spend time on isn’t the data they need to inform real work. Collecting and reporting activity or output data for someone higher-up to (possibly) use doesn’t help a local official make a better plan or management decision. So agencies and governments need to invest more time and money in the right data—and probably request less activity/output reporting. Many local-level respondents were hungry for data on the outcomes of their work; they wanted to know what they were accomplishing so they could act accordingly. This means more investment in censuses, disaggregated household surveys, and especially civil registration/vital statistics. But at the same time, people need unique local data to answer local questions that help them deal with local issues. So instead of just driving data collection from the top, we should make more funds available for locally-driven, smaller-scale data collection.

Making data analysis worthwhile: Nearly every institution in the world struggles to use data well. Local governments/implementers are no different. The main issue is not that people don’t have data skills (even though they often don’t)—it’s that they don’t have incentives to worry about data. Imagine you’re a local government health

Digital v Analogue

official. You don’t have many resources anyway, so a “data-driven decision” may already be something of a moot point. And even if you do have some resources to move around, and you base your decision on good evidence, no one really pays much attention. It probably doesn’t mean recognition or promotion, even if things go well. Then say you’re told that you need to base your budget on data and evidence, so you spend extra hours making a solid proposal for the coming fiscal year. In return, you get the same budget you got last year, minus 10%, and no feedback on your data-driven proposal. After a few years of that, it’s no surprise that many people told us the general consensus when it comes to data is “why bother?” (to offer another anecdote, in Indonesia, local government officials used to refer to budget allocations with a term that literally translates to “bird droppings”).

While incentives issues are hard to tackle, we need to try. Data funders should make practical investments in incentives. For example, awards, prizes, or publicity for dynamic data-users. Or getting a line about “how did this person use evidence to inform their work?” into the form used to conduct annual performance reviews for public servants. Or working with a permanent secretary to recognize and publicly praise a few high-performing data users in her agency.

Creating space for action: We did come across a few impressive people who are intrinsically motivated to use data to make change happen. For example, one dynamic district health official had observed a concerning trend: maternal death rates were high in some communities in her district, but not others. She found that the problem was resource allocation—in particular, that some communities were not supporting enough community health workers. So she presented basic evidence to the district council, comparing local mortality rates to district targets, visualizing which communities had the highest mortality rates, and tabulating the factors that contributed to these deaths. The  response to this public discussion of data was loud and fast. Representatives from under-performing communities scrambled to fund more health workers. Community groups were given a mandate to educate citizens on maternal mortality issues. And over the course of a couple of years, district maternal mortality rates were cut in half.

response to this public discussion of data was loud and fast. Representatives from under-performing communities scrambled to fund more health workers. Community groups were given a mandate to educate citizens on maternal mortality issues. And over the course of a couple of years, district maternal mortality rates were cut in half.

What makes this story unique is not that special data was available, or that sophisticated analysis was done. Instead, one leader saw an opportunity to make change with data, and had the desire to do something about it. In addition to promoting incentives, our investments should create space for similar local leaders to do something different as a result of data-driven insights.

At a high level, this means that money and data need to be tied more closely together. So big donor investments in results-based financing and public finance reform should be seen as a critical part of the data revolution. But at a local level, we can find easier ways to link financial data with population and results data (like the example above). We can make small implementation grants available to local-level actors who have new ideas, based on evidence, that they want to carry out. And we can offer training that is as much (or more) about communication and political navigation as it is about data cleaning and analysis.

So what: What this boils down to is that local development actors want to use data to make their work more effective. They need more data, but it needs to be the right data—so we should be judicious and decision-focused when funding new data collection. They need training and tools, too, but these are just stepping-stones. To make change happen, international data revolutionaries need to make bold investments that foster incentives and create space for local actors to use data to do something new.

November 30, 2016

Are we heading for another debt crisis? If so, what should we be doing?

Just when you thought life couldn’t get more retro (Leonard Cohen on the radio, post-Brexit trade negotiations, impending nuclear war), here comes another debt crisis. Probably. Had a good briefing from some key wonks in Development Finance International and the Jubilee Debt Campaign, two small but vital watchdogs that play a vital role in maintaining capacity on important issues when they drop down the policy agenda a bit – see JDC’s recent paper on Ghana’s debt, or DFI’s work on government spending in poor countries. Such outfits can sound the alarm with some authority when they spot bad stuff coming down the line, which is what they were doing with us last week.

negotiations, impending nuclear war), here comes another debt crisis. Probably. Had a good briefing from some key wonks in Development Finance International and the Jubilee Debt Campaign, two small but vital watchdogs that play a vital role in maintaining capacity on important issues when they drop down the policy agenda a bit – see JDC’s recent paper on Ghana’s debt, or DFI’s work on government spending in poor countries. Such outfits can sound the alarm with some authority when they spot bad stuff coming down the line, which is what they were doing with us last week.

They see another debt crisis for the poorest countries, albeit with a few differences compared to last time (the 90s and 00s). Debt service as a percentage of government spending in low and low-middle income countries is up to an average of 27% of total government revenue, which is a pretty severe burden on cash-strapped countries that really need to spend on schools, hospitals, infrastructure etc.

Triggers for the current squeeze include some similar factors to the last time: the commodity price crash has starved governments of revenues with which to service their loans, especially in countries that have failed/been unable to diversify out of commodity dependence. Potential rising dollar interest rates could add to the pressure (and the retro feel).

Not looking good

Main differences this time around are:

Much greater role for domestic debt, i.e. governments borrowing from their citizens, or in their own currencies, often at much higher interest rates than for international loans

Greater role for international bonds – lots of governments have entered bond markets, partly to send signals of their market friendliness: issuing international bonds has become the modern version of setting up a national airline – a symbol of national pride.

The rich countries have contributed by switching aid from grants to loans, encouraging Private Public Partnerships (which load future debt service onto governments) and generally pushing private sector solutions and ‘financial deepening’ in a pretty undiscriminating way. Cue lots of banks and other lenders spotting big profits and piling in.

Some of the sources of vulnerability to crashes are also familiar: there is still no agreement on a way for countries to restructure their debts along the lines of private sector bankruptcy proceedings; as the debt burden rises, lenders are once again starting to do circular lending – issuing new loans that are just used to service old ones, allowing countries to maintain the appearance of keeping up with their repayments but at the cost of spiralling debt with few benefits to local citizens.

Many in the IMF and World Bank are concerned and are revising their ways of looking at debt levels to take more account of domestic debt and PPPs. The IMF even warned strongly about rapidly growing debt burdens during its recent Annual Meetings. But some in the multilateral development banks and aid agencies are heavily invested in PPPs as a solution for infrastructure financing, and are reluctant to accept that they have been fuelling the problem.

So if debt campaigners are going to scale up, get back on the Jubilee 2000 horse etc, what might  work?

work?

The first issue is to get the debt problem on the agenda – that means bearing witness, killer facts on how much health care and education is being eaten up by debt service payments. Support from influential economic journalists like Larry Elliott also helps. Developing country governments are reluctant to sound the alarm for fear of precipitating just such a crisis, so in their absence maybe get some irreproachable global authority figures to say there’s a problem (the Pope? Gordon Brown? Kofi Annan?)

Another challenge is to start thinking through the responses at national level. It’s all very well pissing off international markets, but the politics of alienating your middle class creditors by restructuring your domestic debt can be very toxic – witness the El Barzón movement which led to the ousting of a 70 year ruling party in Mexico in the mid 90s. One potential ally is the many CSOs that have got involved in budget monitoring and accountability work, who could form the core of a revived interest in debt. Another is parliaments in developing countries that want to hold their governments to account.

Intellectually the far greater level of policy interest in inequality should help to focus minds, as debt exacerbates inequality by giving large profits and interest payments to the wealthier, but loading the burden of crises onto the poor through spending cuts), and taxation (as an alternative to debt).

What would help is a clear narrative on what we are for, as well as what we are against – what constitutes responsible lending/borrowing, and where has it taken place? In terms of lending, UNCTAD and CSOs have proposed some clear guidelines, and some governments have been more responsible by continuing to provide grants and very cheap loans to poorer countries. On the borrowing side, Ethiopia and Rwanda have borrowed somewhat more wisely , building up the economy without racking up very high debt service – human rights advocates aren’t going to like that, so any others?

Modern Slavery?

In terms of old-school ‘problem/solution/villain’ campaigning, PPPs and Vulture Funds provide some handy villains, and deserve a good kicking.

But one thing that’s changed since the 1990s is that domestic civil society is calling the shots far more these days. CSOs in Mozambique and Ghana reportedly don’t just want debt cancellation – they want to make sure the crisis leads to greater levels of transparency and accountability, rather than simply letting off a ‘bunch of crooks’.

There’s also a challenge for any Northern campaign, when supporters say ‘didn’t we already fix this?’

There are two answers to this – one that we didn’t fix the system which leads to rapid debt growth, just the symptoms of debt crisis, and two that many of the countries affected now are different from those which were “fixed” before (as previous debt relief went to only the poorest and most indebted countries).

Finally, there will be crises, and those constitute ‘critical junctures’ for a campaign – how campaigners prepare in advance, and respond to those crises will be decisive.

Anyone else thinking about this?

November 29, 2016

Are these the worst aid agency road-side signs ever? Send in your candidates

Jonathan Tanner is communications manager at the

Africa Governance Initiative (check out their new ‘art of delivery’ paper)

. Here he calls out some truly dire communication by aid agencies

new ‘art of delivery’ paper)

. Here he calls out some truly dire communication by aid agencies

I was recently in Sierra Leone and Liberia to record a series of podcasts for AGI. The things I saw ranged from the jaw-dropping beauty of dawn on the road out of Freetown to the gut-wrenching destitution of the poorest residents of Monrovia. Yet it was something much more ordinary that provoked a range of bewilderment and disbelief in me as the towns and villages went by. I can’t be the only one who has laughed and almost cried at some of the ludicrous signs erected by development agencies on roadsides around the world. Call me a communications geek but some of these signs are physical embodiments of the worst gobbledegook tendencies of the aid industry.

But why do a few pointless or ineffective signs matter? Well in rural Montserrado one group of locals refer to their hometown as ‘low cost village’ named after an otherwise long forgotten UN-led agriculture project. Jargon has taken root in the real world.

But why do a few pointless or ineffective signs matter? Well in rural Montserrado one group of locals refer to their hometown as ‘low cost village’ named after an otherwise long forgotten UN-led agriculture project. Jargon has taken root in the real world.

It’s easy to laugh and often we should – but behind the humour lies wasted money and wasted opportunities to address real problems.

I saw four types of signs on my trip but I’m willing to bet there are more.

First are the development partner public information efforts. Many of these are rusty and outdated but by no means all. One sign sporting a Christian Aid logo (among others) features a picture of a parrot, a crab and a tilapia and exhorts Sierra Leoneans to ‘stop destroying our lives’ but offers no clue as to how. A UN Women billboard warns against under-age sex and tries to make use of imagery as well as text to get its point across but largely fails. Text is after all a questionable  communications tactic in a country where over a third of adults can’t read.

communications tactic in a country where over a third of adults can’t read.

Second is the project recognition sign, usually stationed beside a piece of infrastructure and emblazoned with a donor logo or national flag. Ok so these signs are not really for the benefit of the local population, they probably exist more the benefit of development partners but still, they are a waste of money. I’ve heard tell of significant five figure sums being spent on consultants drafted in by donors to brand public infrastructure projects. Ok, there’s also a serious purpose to some of these signs, one associate wishes we had more of them here in the UK to point out the contribution of the EU coffers to the UK’s infrastructure but we’re probably some way off a referendum on the future of aid flows to any developing country.

Third is the government commissioned public information sign. These are often really bad. Some

Third is the government commissioned public information sign. These are often really bad. Some

look like development project bid documents painted freehand onto a sheet of a metal, others extol the virtue of ‘capacity building’ and other such development clichés.

Fourth and final were the more recent public health adverts aimed at stopping the spread of Ebola. Many of these are much better, making strong use of images and conveying concrete messages not abstract ideas about corruption or climate change.

I haven’t worked for the sort of organisation that would get involved in public information projects like these but I’d be interested to hear from people who have. It’s possible these signs don’t cost much money, or all the examples that piqued my curiosity are out of date. Perhaps they’re proven to work and I’m just being cantankerous or maybe those communications-savvy staff attempting to address the issue are downtrodden and overruled. There’s lots to be learned from advertising agencies and other communication experts about how to get messages across. Surely we can do better than this?

Over to you: send me [dgreen[at]oxfam.org.uk] your photos of terrible aid signs, and a line on why you hate it, and we’ll have a vote. I suspect there are a lot worse than these ones sitting out there by the roadsides.

November 28, 2016

What role for local actors in system change? Fighting climate change in the UK

Ruth Mayne, Oxfam’s senior researcher on the effectiveness of influencing, reflects on some  personal influencing she was involved with before (re)joining Oxfam.

personal influencing she was involved with before (re)joining Oxfam.

In the development world we often emphasise the importance of strengthening community action but is it really possible for local, rather than national and international, actors to contribute to system change? And if so, why and how does this happen, and under what conditions?

Building on Duncan’s new book, I want to share some learning about how grass roots action can contribute to system change. Although focused on local carbon reduction efforts in Oxfordshire, the insights are relevant to other development areas characterised by socio-technical transformations, such as health and agriculture.

Somewhat unusually, I was involved in both making local change happen as a resident and subsequently researching it with colleagues at the Environmental Change Institute where I was working at the time. We decided to use the Multiple Level Perspective of Transition Theory – a type of system theory – to help analyse county-level efforts to build a low carbon economy. This theory sees change as occurring through the interaction of three system levels that are characterised by their degree of resistance to change:

Niche – micro level spaces often located outside the mainstream where socio-technical innovation can occur, including grass roots or community innovations.

Regime – meso level dominant socio-technical practices, standards, rules, and infrastructures.

Most resistant Landscape – slow changing macro level markets, demography, natural environment, and deep rooted cultural values.

As the niche level operates outside the mainstream it is seen as an important potential source of change in contrast to the ‘regime’ which is understood to be largely characterised by ‘lock in’. Opportunities for system change can occur when ‘niche-innovations’ build up momentum (e.g. through the demonstration effect, price/performance improvements or support from powerful groups) and changes in the ‘landscape’ (e.g. climate change, energy insecurity) put pressure on and destabilise elements of the socio-technical regime (manifested in changes in government policy, practices etc), which in turn creates windows of opportunity for niche-innovations to spread. A related field of Transition Management analyses how platforms of government and other national level actors – known as ‘transition arenas’ – can help steer transitions through innovative visioning, and planning, and nurturing niche innovations.

Using Transition Theory as our framework we identified a ‘pre-development’ stage in Oxfordshire (pre-2001) characterised by the uncoordinated development of low carbon ‘niche innovations’ by local authorities and community groups including waste reduction, renewable energy, energy conservation etc. This was followed by ‘take off’ stage (2001-2008) characterised by an increase in the number of low carbon community groups (LCCGs) and the emergence of more coordinated innovations. During this period three local intermediary organisations were formed with support from the County Council and the Environmental Change Institute. They facilitated shared learning between communities enabling both a growth in the number of low carbon communities and niche innovations. This activity was given added impetus by increased ‘landscape’ pressures from climate change including the unprecedented summer flood of 2007.

Using Transition Theory as our framework we identified a ‘pre-development’ stage in Oxfordshire (pre-2001) characterised by the uncoordinated development of low carbon ‘niche innovations’ by local authorities and community groups including waste reduction, renewable energy, energy conservation etc. This was followed by ‘take off’ stage (2001-2008) characterised by an increase in the number of low carbon community groups (LCCGs) and the emergence of more coordinated innovations. During this period three local intermediary organisations were formed with support from the County Council and the Environmental Change Institute. They facilitated shared learning between communities enabling both a growth in the number of low carbon communities and niche innovations. This activity was given added impetus by increased ‘landscape’ pressures from climate change including the unprecedented summer flood of 2007.

A social network analysis carried out by research colleagues (below) shows the dense flows of information and practical support between local organisations that contributed to one of the densest networks of low carbon community groups in the country. Complementary research shows how these groups in turn help change residents’ energy practices (regime).

Receiving of information by survey respondents. Node size is proportional to number of other groups who said they receive information from them

An intensification of the ‘take off’ stage occurred from 2009 onwards marked by the emergence, replication and growth of ‘promising’ innovations. This period saw the creation of two local ‘transition arenas’, further local flooding (landscape pressures) and the strengthening of some aspects of government policy (regime changes) particularly the introduction of the Feed in Tariff (FiT) in 2010. The latter incentivised the local generation of clean energy and enabled new business and funding models to be established, and dialogue with government.

During this period my own community group, Low Carbon West Oxford (LCWO), developed a carbon reduction initiative, which we called ‘the double carbon cut’. This involved setting up community benefit coops to generate clean energy and donate the surplus income to a new community led charity to run further community carbon-cutting projects. These projects – home energy use, sustainable transport and food, waste reduction, community tree planting – encourage and support residents to adopt more sustainable lifestyles.

The carbon reductions, demonstrated by monitoring and evaluation data, prompted Oxford city council to invite us to co-design a grant application to government aimed at scaling-up and replicating elements of the model via the establishment of a county-wide social enterprise (the Low Carbon Hub).

Photograph © Low Carbon Hub/ Larkrise School

During this time a city-wide initiative called Low Carbon Oxford was also initiated by Oxford City Council and the Oxford Strategic Partnership. Both the Hub and Low Carbon Oxford behaved like local ‘transition arenas’ by convening a much wider range of actors (large businesses, local universities, NHS etc), creating a shared vision, facilitating collaborative action and ‘nurturing’ promising innovations.

If a favourable national policy environment had been sustained or strengthened Oxfordshire might have moved into an ‘acceleration phase’ of the transition. However, a reduction in the FiT, damaging changes to home energy policy and an ambitious local economic growth drive have slowed this development, hopefully temporarily, although local actors continue to seek new business models, spread innovations, and widen public engagement.

The use of system theory helped highlight how interactions between system levels can promote and constrain change. However, on its own it does not necessarily tell you much about the purposeful change strategies that actors use to contribute to system change. So in our research we grouped and assessed local actors’ strategies according to whether they were down-stream with residents (engagement, empowerment, innovation, adoption of low carbon technologies, behaviour change), midstream with other local actors (dissemination, growing and mainstreaming) and/or upstream with national actors (influencing national government).

In the initial period local actors in Oxfordshire expended most of their energy on achieving down- and mid- stream change. The subsequent weakening of the national policy framework arguably now highlights the need for a greater emphasis on upstream strategies to influence government policy. There are hundreds of low carbon communities around the country with considerable (often untapped) sources of soft power linked to the legitimacy they derive from being ordinary citizens (vs professional campaigners), their voluntary action and their practical knowledge. Although as volunteers they are highly time-constrained, with funding and support from national actors, they could play a valuable role in a mass public campaign aimed at ensuring a relevant, strong and equitable national policy framework and incentive structure to support the low carbon transition.

November 27, 2016

Links I Liked

In the US for next two weeks (Washington, New York and Boston). Here’s a list of public events if you want to come and discuss How Change Happens (seems pretty relevant right now, huh?)

What is a Muslim? Funny, smart and very effective 3m video.

Best/Worst charity ads of the year. Rusty Radiator awards now open for voting – get stuck in. Background here

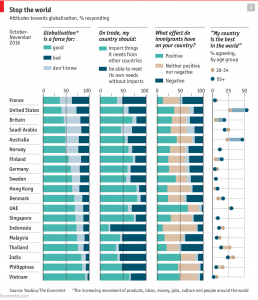

Two important Economist charts to mull over (click to expand): What people care about, and attitudes to globalization

Two important Economist charts to mull over (click to expand): What people care about, and attitudes to globalization

Why is the World Bank ‘Doing Business’ flagship promoting a race to the bottom on corporate taxes? José Antonio Ocampo and Valpy Fitzgerald on the warpath.

Some new/potentially helpful angles on the US elections. Poor health was an even better predictor than education i US voting behaviour. And amid all the uncertainty and guesswork, Italy’s Silvio Berlusconi may not be a bad guide to what to expect.

An animated map of 40 years of rising obesity: disturbing animation, especially for all those recovering from Thanksgiving blowouts…..

A perfect illustration of ‘build bridges not walls’. Utterly lovely 5m video where refugees and others are asked to look into each other’s eyes.

November 24, 2016

Friday rant: ‘development’ is not the same as ‘aid’. Got that?

A recent headline in my RSS feed flicked my ‘Activate Rant’ button. ‘This Video from Uganda Highlights Everything  Wrong with Global Development’ it shouted. I knew what the video was about – some young white American missionaries getting into trouble for ‘dressing up native’ and singing ‘get your mission on’ provoked outrage in various quarters. I hadn’t found it interesting enough to blog or even tweet about.

Wrong with Global Development’ it shouted. I knew what the video was about – some young white American missionaries getting into trouble for ‘dressing up native’ and singing ‘get your mission on’ provoked outrage in various quarters. I hadn’t found it interesting enough to blog or even tweet about.

But what got me riled was the headline’s claim that this had something to do with ‘global development’ – you know, that amazing process whereby billions of people have worked their way out of poverty, sometimes with the help of/sometimes in spite of their local nation states. What on earth did these kids capering about in a road in East Africa have to do with that? Answer, nothing. Once again, we seem incapable of grasping that ‘aid’ and ‘development’ are two largely (and increasingly) separate things.

I have a similar beef with the term ‘development effectiveness’. If you take Amartya Sen’s definition of development as the expanding freedoms to be and to do, then development is always effective – the combination is redundant. What the phrase really seems to mean is ‘effectiveness of aid, plus other international flows that don’t qualify as aid, like foreign investment’. OK, we need a new term for that wider flow of money, but why on earth call it ‘development’?

Shackling something huge and life-changing (development) to something much less important (aid) is a form of self-aggrandisement by the aid sector that takes me back to my disgruntlement with the overclaiming around the Make Poverty History campaign. Sort out aid, trade and debt and ‘we’ (whoever ‘we’ are) can MPH. Um, no ‘we’ can’t – does anyone really believe that? What will make poverty history is national development, politics, the evolving social contract between citizens and states, with ‘us’, as in the aid business in a role that is always secondary and sometimes (think China) irrelevant. That makes campaigners, aid workers etc always a sidekick in the drama – we can aspire to be Robin, but never Batman.

Shackling something huge and life-changing (development) to something much less important (aid) is a form of self-aggrandisement by the aid sector that takes me back to my disgruntlement with the overclaiming around the Make Poverty History campaign. Sort out aid, trade and debt and ‘we’ (whoever ‘we’ are) can MPH. Um, no ‘we’ can’t – does anyone really believe that? What will make poverty history is national development, politics, the evolving social contract between citizens and states, with ‘us’, as in the aid business in a role that is always secondary and sometimes (think China) irrelevant. That makes campaigners, aid workers etc always a sidekick in the drama – we can aspire to be Robin, but never Batman.

Words matter, and conflating development and aid is both politically and factually wrong. Rant over. Very therapeutic – do you mind if I do more of these?

And here’s the offending video for anyone who missed it (sorry, it’s been removed from youtube after the furore, so can’t embed it)

And you may now vote

You probably don’t want to know

Note: There is a poll embedded within this post, please visit the site to participate in this post's poll.

November 23, 2016

Payment by Results in Aid: What’s new?

Development Economist

Paul Clist

discusses some of the ideas from his new paper

(

Link to paywalled article

version

,

link to free draft version

)

version

,

link to free draft version

)

Payment by Results (PbR) is a fairly new idea in aid, where a donor decides how much money to disburse on the basis of how much a recipient has achieved against a target. For example, a donor could pay an NGO for how many wells it installs, or a government on the basis of their vaccination rate. I’ve got a new paper that puts some meat on the bones of the standard development/social science points that this isn’t a silver bullet and context matters, so read it if you wish to know when we should expect PbR agreements to work. To give you a flavour, it looks at three bits of a PbR agreement: the measure, the agent (i.e. recipient) and the principal (i.e. donor). You may not like these terms, but it does mean we a nice acronym -MAP.

Rather than just summarize the paper, here are two themes which are new to my thinking on PbR.

PbR will ‘honestly’ mislead

But what exactly is being measured?

When people first hear about PbR, a common concern is fraud: that the recipient will simply lie or cheat the measure. I think these concerns tend to be well understood, and so aren’t much of a problem. What I hadn’t fully appreciated was the capacity of PbR to ‘honestly’ mislead, in other words when the measures will report success when there is none. The paper gives three examples. In one case, national governments received payments for improvements in vaccination rates that didn’t actually happen, because of subtle incentives in data reporting. In another, PbR seems to have successfully changed health outcomes in Indonesia. However, a return visit shows PbR simply changed when improvements occurred, with no discernible impact in the long run. In another case, PbR was used to incentivise school feeding programs in China as a way to fight anaemia. While it had the desired effect on school feeding programs, kids in these schools actually did worse in their exams.

In each of these cases the goal of the donor was not met, but PbR reported success and the donor disbursed aid. I don’t think there was a deliberate and dishonest attempt to mislead donors, but rather a more complicated and subtle process. The obvious application for those wishing to do PbR is that the quality of the measure is the biggest determinant of whether PbR will work.

There are more subtle points here too. I called the new paper fool’s gold because I’m worried that not everything that looks like evidence of PbR’s success is genuine. The ‘success’ in the examples above was false, but we only know this because there was other data to investigate. Normally, that won’t be the case. Morten Jerven calls this ‘policy-based evidence’, because PbR reduces the quality of the data, in a way that favours the policy in question. If we had lots of lovely data that would be fine, but we don’t. If the data we do have becomes less accurate because they are used as indicators, PbR will not only look more useful than it is, it will reduce our ability to learn about all sorts of things.

looks like evidence of PbR’s success is genuine. The ‘success’ in the examples above was false, but we only know this because there was other data to investigate. Normally, that won’t be the case. Morten Jerven calls this ‘policy-based evidence’, because PbR reduces the quality of the data, in a way that favours the policy in question. If we had lots of lovely data that would be fine, but we don’t. If the data we do have becomes less accurate because they are used as indicators, PbR will not only look more useful than it is, it will reduce our ability to learn about all sorts of things.

Complexity and Markets: Time to leave those models behind

One of the intellectual attractions to PbR is that it appears to offer sensible solutions in a complex world, where donors let recipients discover the best way of doing things and simply focus on the results. Another mental model that seems to attract people to PbR is that it looks a bit like a market. If you’ve some grasp of economics, PbR looks a lot like paying a recipient to produce development outcomes.

I don’t think either of these mental models is particularly helpful. On complexity, we can think of a case where a single indicator (e.g. the number of soap flakes, to use Tim Harford’s example from Adapt) allows someone to discover the best way of operating (through trying random variations of different nozzles). In this example we have a complex process, lots of feedback loops and iteration towards an optimal solution. While this is an interesting mental model, most PbR projects are a) much more complex than this and b) have a fraction of the feedback. In their book on PbR, long time advocates the Center for Global Development set out a coherent model of PbR. However, while CGD recommended PbR projects run over a minimum of 5-10 years, this simply isn’t happening. Whether it is even possible, given institutional constraints, remains to be seen. The kinds of things that PbR is trying to disburse on are also incredibly complex, where genuine improvements may take longer than a few years to even start showing signs of working.

The paper also discusses a little the latest research on innovation, which recommends not punishing failure in early stages, but giving handsome rewards over a period of time later in the contract. That is a long way from a three year contract for a complex outcome and limited feedback.

The paper also discusses a little the latest research on innovation, which recommends not punishing failure in early stages, but giving handsome rewards over a period of time later in the contract. That is a long way from a three year contract for a complex outcome and limited feedback.

On markets, while a first look sees similarity between markets and PbR, economists tend to be quite sceptical. The paper applies the multitask model to PbR, a model discussed at length by the recent Nobel prize winner Bengt Holmstrom. The main message is simply that a good measure is much harder to find than you’d think, with the above example of Chinese school feeding programs an almost perfect demonstration of the multitask model.

Let’s not hype

My main concern with PbR is not that it will always fail: far from it. Rather, genuine evidence of success will be difficult to distinguish from the kinds of fool’s gold effects discussed above, especially when it is used in unsuitable contexts. If PbR is used in cases where it does more harm than good, this will ultimately lead to a backlash where PbR is used too little.

November 22, 2016

Is it time to move on from Stats and Numbers to Metaphor and Narrative?

Post Brexit and US elections, I’ve been doing some thinking about how we talk to people. It seems to me that, along  with much of the aid and development sector, and quite a few other social change movements, we have been in thrall to the power of numbers and evidence. Everyone is a policy wonk these days.

with much of the aid and development sector, and quite a few other social change movements, we have been in thrall to the power of numbers and evidence. Everyone is a policy wonk these days.

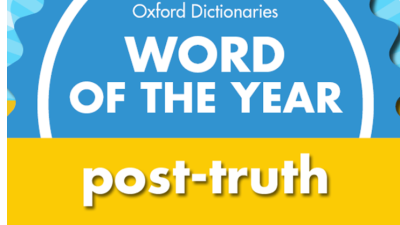

The trouble is, as this year’s political events have shown, we are in a world of public debate that if not exactly post-truth (truth means different things to different people), feels very post-evidence or post-fact. Actually I think it’s probably always been like that, but people were more willing in the past to defer to experts and their alien language. The death of deference (good thing) means they are now no longer willing to do so (not so sure).

So what does this mean for those of us working on progressive social change? I think we need to at least partly put aside our preference for number crunching and lists of policy recommendations, and make greater use of metaphors or narratives instead.

This goes back to the long-standing discussions on framing – what kind of emotions are we trying to evoke? What is the underlying picture of the world? I would say positive emotions like trust, love, pride and self-reliance, laced with anger at injustice and discrimination.

What kind of narrative or metaphor could capture that? As an example, we could do worse than London Mayor Sadiq Khan’s soundbite that we should be building bridges not walls. That seems to conjure up exactly the right blend of emotions – optimism in the face of a threat.

What kind of narrative or metaphor could capture that? As an example, we could do worse than London Mayor Sadiq Khan’s soundbite that we should be building bridges not walls. That seems to conjure up exactly the right blend of emotions – optimism in the face of a threat.

So what could a ‘bridges not walls’ campaign cover? Off the top of my head:

Bridges between communities and nations (anti-racism, better treatment of migrants, fair trade agreements)

Bridges across cyber communities (efforts to span the filter bubbles that divide us – are there apps yet that bring quality analysis from other political/social perspectives into your feeds? If not, someone should design one – here’s some good suggestions for Facebook)

Bridges between rich and poor (social mobility, fair taxation)

Bridges between present and future (education, early years nutrition, climate change, environmental sustainability)

Oxfam’s Head of Global External Affairs, Katy Wright, had some good (if slightly painful) questions on where my

much-loved ‘Killer Facts’ fit into this. ‘Don’t you think “killer facts” are, in a way, part of that post truth landscape? Like all statistics they only tell part of the picture, they are designed to evoke emotions, to give you social currency when you pass them off as your own down the pub, and they’re pretty black and white. The problem with them is that they don’t inspire action or a belief that things can change.’

What do you think? What other overarching (sorry, bridges again) metaphors might get us away from the wasteland of stats and numbers that we have wandered into, and reconnect with a wider public?

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers