Duncan Green's Blog, page 125

February 6, 2017

Want to put together a team to research inequality? LSE may be able to fund you

A 20 year project to build an international network of scholars and activists working on inequality is just kicking off.

Interested? Read on.

The Project is the Atlantic Fellows programme (AFP), run by the LSE’s new-ish International Inequalities Institute and funded by Atlantic Philanthropies, a US foundation (only foundations seem to be able to think on this longer time scale – it’s a really important niche).

The AFP consists of three strands: Residential Fellowships to attend the LSE’s Inequalities and Social Science Masters (MISS); a Non-residential Fellowships that combines about 7 weeks face to face teaching with location and project work; and a programme for visiting researchers, the Visiting Fellowships Programme. That’s an awful lot of fellows, but don’t worry, women can also apply…..

The first two strands have gone live and are massively oversubscribed, so I am mainly interested in getting researchers, campaigners and others to look at the Fellowships Programme, not least because the deadline for applications is 8th March. Here’s the blurb from the leaflet:

‘Teams of three or four researchers can apply to become Visiting Atlantic Fellows, based at the LSE International Inequalities Institute. The Fellows’ teams will conduct intensive research, for periods of between three and nine months, to find potential solutions to the greater challenges posed by inequity.

We are looking for teams that include members from different geographical regions and/or different academic disciplines. We are especially keen to support teams that include members from outside of academia; including figures from civil society organisations, campaign groups, media bodies, and think tanks that focus on inequalities.

Small group session with a lecturer during the University of London International Programmes Study Weekend at the LSE in February 2012

Funding is available to cover most research expenses, including travel, accommodation, research assistance, and more. Office space will be provided at the LSE International Inequalities Institute where the teams will work alongside other Atlantic Fellows from around the world and Research Fellows embedded within the Institute.

Visiting Fellows will also become a part of the community of Fellows – including those from sister programmes in South Africa, USA, Asia and Australia – helping to build an informed and motivated network dedicated to reducing inequalities around the world.

You can apply online or you can contact the programme’s Co-Directors, Prof John Hills or Prof Mike Savage, via afp@lse.ac.uk.’

What is special about this?

It gives you a chance to assemble a dream team to do a particular piece of work on inequality, tapping into LSE’s research and brainpower. It’s like an inequalities boot camp.

It placed a particular emphasis on assembling coalitions of ‘unusual suspects’ – academics and practitioners and/or different academic disciplines (politics, economics, law, journalism etc)

With a 20 year lifetime, it can build up an international alumni network of scholars and activists who can start to really make a difference. That’s the sort of timescale and ambition the Chicago University economics department had when it helped convert Chile into a monetarist lab rat, so great to see it being harnessed for more progressive ends!

One condition – you will need to have an academic from the LSE as part of your team, preferably as an active member, or if not, as a sponsor. And I’m not offering, even though I teach there (I’m also on the advisory panel for the project, hence this plug).

February 5, 2017

Links I Liked

First there’s the search for the best placards – seems like humour is the best response to ugly/angry.

First there’s the search for the best placards – seems like humour is the best response to ugly/angry.

Then there’s the analysis. Are institutions strong enough to withstand disruptive populism? Francis Fukuyama makes the case against panic. The World Bank’s Sina Odugbemi is less sure.

And protest? Excellent lessons from Tina Rosenberg on lessons from We wprevious waves

As for longer reads, try What Trump is Throwing out of the Window in NYRB

But what do we tell our kids? Global Voices suggested some ‘Classic Cartoons That Took on Dictatorship‘ (Smurfs, Donald Duck, Lucky Luke etc). How about some more recent versions – Simpsons? South Park (my kids tell me there’s a South Park on every issue)? Suggestions and links please.

On other news, we want to turn How Change Happens into a MOOC (Massive Open Online Course). Are you a MOOC designer? If so come and work with me for 6 months. Deadline for applications 19th Feb. Also, I’m speaking in Stockholm on 13th and Dublin on 15th, if you’re around

Watch two tough women go head to head – Winnie Byanyima (Oxfam CEO) v Zanny Minton Beddoes (Economist  editor) jousting in Davos (6m video)

editor) jousting in Davos (6m video)

Monty Python’s take on good governance cropped up in Chris Blattman’s course outline on order and violence and in a tweet that went viral, so treat yourself to this

February 2, 2017

Of Jousting Knights and Jewelled Swords: a feminist reflection on Davos

Nancy Folbre is a feminist economist and professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst

What kind of an economic system delivers as much wealth to 8 men at the top as to the bottom half of the global population? It’s easier to describe shocking levels inequality than to explain them.

Activist challenges to the power of the top 1%–along with demands for the empowerment of the 99%– have moved way ahead of academic theorizing about the dynamics of global capitalism. Attention to the concentration of wealth challenges the time-honored distinction between those who own the means of production and those who work for wages. It highlights not only stark inequalities among owners, but also the gender, race, and citizenship of men at the top.

These men own their own forts and fly their own flags. Politicians are their minions. This sounds like patriarchal feudalism or colonialism to me. The economy we inhabit bears little relationship to textbook descriptions of a competitive system that encourages innovation and rewards hard work. Our economic labels, as well as theories, seem out of date.

Social scientists in general and economists in particular cling to a vision of patriarchy, feudalism and colonialism as anachronistic systems, stages of development supplanted by something they call capitalism. But the economic system we inhabit consists of layered hierarchies in which new forms of privilege crystallize on top of ancient pyramids.

Social scientists in general and economists in particular cling to a vision of patriarchy, feudalism and colonialism as anachronistic systems, stages of development supplanted by something they call capitalism. But the economic system we inhabit consists of layered hierarchies in which new forms of privilege crystallize on top of ancient pyramids.

Global capitalist dynamics are driving many economic trends. But their directions and their consequences are predetermined by the unequal distribution of many different forms of wealth. The financial assets that Oxfam’s recent report documents are the easiest to quantify. But access to education, workplace opportunities and the languages of power are also assets to be capitalized.

Most capitalists today are like the jousting knights of old, the few who could afford the horses, armor, servants, and jewel-encrusted swords required to even enter into competition.

Capitalist dynamics undermine some inherited privileges, but creates new hybrid forms: intersecting shards of gender, race, citizenship, class and other dimensions of socially assigned identity. The many exploitations of the past make current exploitations easier, creating fractal inequalities that hinder efforts to build political coalitions of the disempowered.

The system we inhabit is not capitalism, but capitalist plutocracy. A capitalist democracy would look quite different. It would give the 99% the assets needed to invest in an equitable and sustainable economic future.

February 1, 2017

Multinational Companies in retreat? Fascinating Economist briefing

Now we’re all looking for ways to break out of filter bubble, I guess I can feel less guilty about loving The Economist. Beautifully written, it covers places and issues other papers ignore, and every so often has a big standback piece that makes you rethink. This week’s cover story, ‘the retreat of the global company’, is a fine example. Excerpts from the 4 page briefing:

Now we’re all looking for ways to break out of filter bubble, I guess I can feel less guilty about loving The Economist. Beautifully written, it covers places and issues other papers ignore, and every so often has a big standback piece that makes you rethink. This week’s cover story, ‘the retreat of the global company’, is a fine example. Excerpts from the 4 page briefing:

‘25 years ago, with the Soviet Union collapsing and China opening up, a sense of destiny gripped Western firms; the “end of history”, in which all countries would converge towards democracy and capitalism.

Companies became obsessed with internationalising their customers, production, capital and management, enthusiastically buying rivals, courting customers and opening factories wherever the opportunity arose. Though the trend started in the rich world, it soon caught on among large companies in developing economies, too. And it was huge: 85% of the global stock of multinational investment was created after 1990, after adjusting for inflation (see chart 1).

Such a spree could not last forever; an increasing body of evidence suggests that it has now ended. In 2016 multinationals’ cross-border investment probably fell by 10-15%. Impressive as the share of trade accounted for by cross-border supply chains is, it has stagnated since 2007 (see chart 2). The proportion of sales that Western firms make outside their home region has shrunk. Multinationals’ profits are falling and the flow of new multinational investment has been declining relative to GDP. The global firm is in retreat.

To understand why this is, consider the three parties that made the boom possible: investors; the “headquarters countries” in which global firms are domiciled; and the “host countries” that received multinational investment.

To understand why this is, consider the three parties that made the boom possible: investors; the “headquarters countries” in which global firms are domiciled; and the “host countries” that received multinational investment.

Investors saw a huge potential for economies of scale. As China, India and the Soviet Union opened up, and as Europe liberalised itself into a single market, firms could sell the same product to more people. And as the federation model was replaced by global integration, firms would be able to fine-tune the mix of inputs they got from around the world—a geographic arbitrage that would improve efficiency. From the rich world they could get management, capital, brands and technology. From the emerging world they could get cheap workers and raw materials as well as lighter rules on pollution.

These advantages led investors to think global firms would grow faster and make higher profits. That was true for a while. It is not true today. The profits of the top 700-odd multinational firms based in the rich world have dropped by 25% over the past five years. The profits of domestic firms rose by 2%.

Individual bosses will often blame one-off factors: currency moves, the collapse of Venezuela, a depression in Europe, a crackdown on graft in China, and so on. But the deeper explanation is that both the advantages of scale and those of arbitrage have worn away. Global firms have big overheads; complex supply chains tie up inventory; sprawling organisations are hard to run. Some arbitrage opportunities have been exhausted; wages have risen in China; and most firms have massaged their tax bills as low as they can go. The free flow of information means that competitors can catch up with leads in technology and know-how more easily than they used to. As a result firms with a domestic focus are winning market share.

In the “headquarters countries”, the mood changed after the financial crisis. Multinational firms started to be seen as agents of inequality. They created jobs abroad, but not at home. The profits from their hoards of intellectual property were pocketed by a wealthy shareholder elite. Political willingness to help multinationals duly lapsed.

Of all those involved in the spread of global businesses, the “host countries” that receive investment by  multinationals remain the most enthusiastic. The example of China, where by 2010 30% of industrial output and 50% of exports were produced by the subsidiaries or joint-ventures of multinational firms, is still attractive.

multinationals remain the most enthusiastic. The example of China, where by 2010 30% of industrial output and 50% of exports were produced by the subsidiaries or joint-ventures of multinational firms, is still attractive.

But there are gathering clouds. China has been turning the screws on foreign firms in a push for “indigenous innovation”. Bosses say that more products have to be sourced locally and intellectual property often ends up handed over to local partners. Strategic industries, including the internet, are out of bounds to foreign investment. Many fear that China’s approach will be mimicked around the developing world, forcing multinational firms to invest more locally and create more jobs—a mirror image of the pressures placed on them at home.

The jobs and exports that can be attributed to multinationals are already a diminishing part of the story. In 2000 every billion dollars of the stock of worldwide foreign investment represented 7,000 jobs and $600m of annual exports. Today $1bn supports 3,000 jobs and $300m of exports.

The last time the multinational company was in trouble was in the aftermath of the Depression. Between 1930 and 1970 their stock of investment abroad fell by about a third relative to global GDP; it did not recover until 1991. Some firms “hopped” across tariffs by building new factories within protectionist countries. Many restructured, ceding autonomy to their foreign subsidiaries to try to give them a local character. Others decided to break themselves up.

Today multinationals need to rethink their competitive advantage again. Some of the old arguments for going global are obsolete—in part because of the more general successes of globalisation. Most multinationals do not act as internal markets for trade. Only a third of their output is now bought by affiliates in the same group. External supply chains do the rest. Multinational firms no longer have a lock on the most promising ideas about management or innovation.

Many industries that tried to globalise seem to work best when national or regional. Retailers such as Britain’s Tesco and France’s Casino have abandoned many of their foreign adventures. America’s telecoms giants, AT&T and Verizon, have put away their passports. Financial firms are focusing on their “core” markets.

Many industries that tried to globalise seem to work best when national or regional. Retailers such as Britain’s Tesco and France’s Casino have abandoned many of their foreign adventures. America’s telecoms giants, AT&T and Verizon, have put away their passports. Financial firms are focusing on their “core” markets.

It looks as if, in the future, the global business scene will have three elements. A smaller top tier of multinational firms (e.g. General Electric) will burrow deeper into the economies of their hosts, helping to assuage nationalistic concerns.

The second element will be a brittle layer of global digital and intellectual-property multinationals: technology firms, such as Google and Netflix; drugs companies; and companies that use franchising deals with local firms as a cheap way to maintain a global footprint and the market advantage that brings. The hotel industry, with its large branding firms such as Hilton and Intercontinental, is a prime example.

The final element will be perhaps the most interesting: a rising cohort of small firms (‘multinationalettes’) using e-commerce to buy and sell on a global scale.

The result will be a more fragmented and parochial kind of capitalism, and quite possibly a less efficient one—but also, perhaps, one with wider public support. And the infatuation with global companies will come to be seen as a passing episode in business history, rather than its end.’

January 31, 2017

Watching Oxfam morph into an interdependent networked system

He’s clearly fascinated

While I’ve been ivory towering on the book for the last couple of years, Oxfam has been going through a wrenching internal reform (wait, don’t click – this gets interesting, honest!). Known as Oxfam 2020, 18 different Oxfam affiliates are slowly and painfully sorting out a single operating system and pushing power down to countries and a new swathe of southern affiliates, all while retaining aspects of their individual identities. Unsurprisingly, it has been messy and difficult.

Last week I spent 2 days in a grim former East German Communist Party hotel by a frozen Berlin lake catching up with 40 people from across Oxfam International – Humanitarian, HR, Finance, big bosses, regional bosses, country bosses – my job was to burble on about how change happens and feed back impressions at the end of each day in a ‘live blog’ – aka someone asking me questions for 5 minutes.

The conversations were optimistic (‘assume good will’ was the ground rule for the discussion) and resonated with the themes of the book. Oxfam appears to be evolving into an interdependent, complex and (on a good day) adaptive system, which is striking because the people in the room had very little time for this kind of talk – Oxfamers are overwhelmingly do-ers, almost viscerally unable to stand outside their roles or Oxfam and think in the abstract – within minutes it was back to ‘we/you have to do this/that’.

Here are the headlines from my daily musings:

Culture and Behaviours dominated. When do they drive or block the process? How to change them?

Drivers: Trust. How to build trust between different affiliates, or across ‘professions’ – humanitarian, advocacy, long term development – emerged as perhaps the over-riding theme. Trust is best built by working together, which is happening increasingly as 2020 proceeds. But we could accelerate it, for example by identifying ‘islands of mistrust’ within the organization (between affiliates, disciplines) and deliberately setting up task teams and buddy systems to build trust there in particular (I was told when at DFID that the French and German civil servants are required to establish buddy arrangements with their counterparts – is that true? If so, could be an interesting model).

There’s an interesting link between trust and rules. In a low trust organization, people default to designing ever-more complex rules governing every aspect of decision making, and then spend their time trying to understand, renegotiate or circumvent them. As trust builds, you can move to taking decisions based on shared values and principles – much more agile and productive. You can also push decisions down nearer the ground (subsidiarity) – essential in complex systems.

There’s an interesting link between trust and rules. In a low trust organization, people default to designing ever-more complex rules governing every aspect of decision making, and then spend their time trying to understand, renegotiate or circumvent them. As trust builds, you can move to taking decisions based on shared values and principles – much more agile and productive. You can also push decisions down nearer the ground (subsidiarity) – essential in complex systems.

Blockers: One old hand said the key to getting stuff done in Oxfam is ‘identify and expand the space for action’, and never start by asking ‘what are the rules’. My version on this blog is ‘move from asking permission (in advance) to asking forgiveness (when I screw up). But all too often, ‘people just want to be told what to do’, which can be disastrous when trying to encourage initiative, innovation, entrepreneurial risk-taking etc.

Interesting discussion on why people are sometimes reluctant to take risks – ‘fear of your boss’ isn’t a very convincing explanation, as Oxfam managers are really not that scary. Possible reasons are that the mission (ending poverty) is so overwhelming that people feel crushed by the prospect of failure; that lack of clarity on the processes just makes it too difficult to get on with stuff; or that in complex systems, your personal relationships and capital are all important to getting things done, so you are very reluctant to earn their disapproval and squander your social capital.

Whatever the reason, the common response is to defer action by kicking stuff upstairs or through ever-widening consultation (email seems perfectly designed for this purpose). The result is ‘treacle’ – progress slows to a crawl; people get pissed off and leave.

Diversity v Simplicity: Diversity in the right places drives creativity. In others it really doesn’t – who wants diverse, incompatible IT or finance systems? Above all what needs to be simple and clear is who takes decisions where. I learned a new acronym (always a high point), RACI – for any process it needs to be clear to each individual whether they are to be Responsible, Accountable, Consulted or Informed.

What to do? There was an emerging focus on identifying the bottlenecks in the system and tackling them (I likened it to finding the muscle knots during a massage session). The best way to disrupt the bottlenecks may not only be directly – eg getting a bunch of HR directors to discuss hiring for adaptive management. Other approaches include identifying positive deviants already emerging in the system and building on them, or mimicking the Santa Fe Institute and putting cross-disciplinary groups together to come up with new ideas.

There is no end point. 2020 is a misnomer – if Oxfam is to be an adaptive organization it will need to set itself up in a way that allows it to evolve permanently. Three thoughts

way that allows it to evolve permanently. Three thoughts

Draw from the Paris Climate Change Declaration, which established a ratchet mechanism whereby countries are expected to come back periodically and up their commitments on emissions reductions. That is a more realistic, dynamic approach than a one off agreement, because lessons and ideas emerge as you go, and as trust grows, new things become possible

What lessons on trust-building can we learn from conflict resolution? Is the Northern Ireland peace process a good model for Oxfam?………

A nice suggestion from one group. Part of 2020 is devolving power from HQs to country teams, so why not ask the countries to rank the affiliate HQs on their performance every couple of years? That could provide an additional mechanism to keep big cheeses in Oxford, Boston, he Hague, Hong Kong etc focussed on what matters.

The optimism and sense of progress was a relief, because this internal process has been eating up a lot of energy in recent years (‘where have you been Oxfam?’ is a phrase often heard from partner NGOs). We need to get an adaptive, evolutionary organization up and running asap so we can get back to the day job. It may be Stockholm Syndrome, but I came away from Berlin thinking we may be getting there.

January 30, 2017

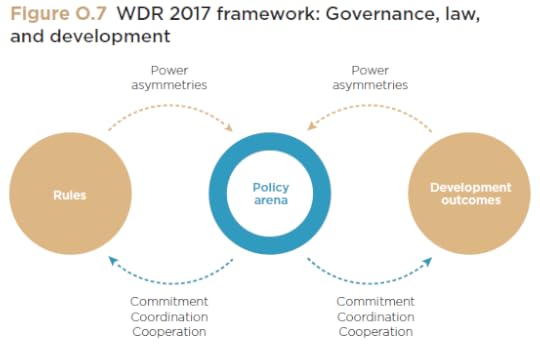

The WDR 2017 on Governance and Law: Can it drive a transformation in development practice?

Stefan Kossoff (DFID’s governance czar) reviews the new WDR, published this week.

For those of us working on governance this week’s publication of the 2017 World Development Report on Governance and Law (WDR17) has been hotly awaited. And I’m pleased to say the report–in all its 280 page glory–does not disappoint (there’s a 4 page summary for the time-starved). As Duncan Green, Brian Levy and others have noted, WDR17 is a landmark report which has potentially far-reaching implications, not just for governance work but for the entire development agenda.

If the Sustainable Development Goals (Goal 16) set the vision for work on “peace, justice and effective, accountable and inclusive institutions”, the WDR performs an important service in elaborating how we might get there. But the WDR17 is consciously not a “blueprint for action” – on the contrary, it provides a compelling argument for why technical blueprints, best practice solutions and other efforts to transplant institutions from one context to another are unlikely to succeed. In so doing it provides a rallying call for a much humbler, more realistic governance agenda which is both politically smart and locally-led.

If the Sustainable Development Goals (Goal 16) set the vision for work on “peace, justice and effective, accountable and inclusive institutions”, the WDR performs an important service in elaborating how we might get there. But the WDR17 is consciously not a “blueprint for action” – on the contrary, it provides a compelling argument for why technical blueprints, best practice solutions and other efforts to transplant institutions from one context to another are unlikely to succeed. In so doing it provides a rallying call for a much humbler, more realistic governance agenda which is both politically smart and locally-led.

This WDR is different from previous WDRs because it asks not “what” needs to change for development to happen, but “why” policy and institutional reforms often fail, including many of those (like anti-corruption commissions) prescribed by the IFIs. Drawing on an impressive range of historical examples—from Ancient Greece to modern day China, Brazil and Somaliland amongst many others—the WDR rehearses some familiar but important arguments about the centrality of institutions for a range of development outcomes including peace, growth and equity; the importance of institutional “function over form”; and the critical role that political power plays in shaping the nature and pace of change.

While the message that “politics matters” may not be a new one, the fact that the World Bank—with its apolitical  mandate—is saying it, is hugely significant. The emphasis on “elite bargains”, citizen engagement and international action in promoting governance change certainly feels a long way from the technocratic reform agenda of the 1990s.

mandate—is saying it, is hugely significant. The emphasis on “elite bargains”, citizen engagement and international action in promoting governance change certainly feels a long way from the technocratic reform agenda of the 1990s.

But articulating this argument is one thing, actually acting on its implications is quite another. So the big question is whether the WDR can genuinely lead to a transformation in aid practice both in the World Bank and beyond.

The jury is currently out but there is certainly scope for some optimism. The Bank has committed to “operationalise” the WDR17 as part of the IDA 18 replenishment package. (The International Development Association is the World Bank lending arm for the world’s poorest countries. Every three years donors meet to replenish IDA resources and review its policy framework.) The details have still to be fleshed out, but this could herald a significant change in the way the Bank works – for example in the area of economic policy where the emphasis on “best fit” and politically-feasible advice would represent a decisive shift away from best practice orthodoxy. The WDR also provides an opportunity to forge a concrete agenda for action across the wider development community, linking with existing initiatives around “thinking and working politically”, “going with the grain” and “doing development differently”. To kick off the discussion, I would identify the following as important elements of that agenda:

Make the WDR17 relevant for everyone working on policy and institutional reform . The WDR will be a wasted opportunity if it is only preaching to the converted in the governance community. As the report argues, governance needs to be “front and centre” of work on economic development, conflict and service delivery. But this means winning hearts and minds amongst economists and education, health and infrastructure specialists too. We also need to break out of our aid silos and collaborate with partners across government to address common challenges arising from corruption, crime and instability.

Fully embrace a politically smart, flexible and adaptive approach to aid delivery, completing our evolution away from technical blueprints

. This means more development strategies and programmes which address the political as well as technical barriers to development progress. As Alan Hudson points out, it also means creating the systems and processes which allow for more flexible and adaptive working – including better problem diagnosis; more innovative approaches to procurement and contracting; greater investment in monitoring, evaluation and learning; and new skills and capabilities for staff. Lastly, it means a fundamental change in organisational culture so staff are empowered and incentivised to think politically and work flexibly.

Fully embrace a politically smart, flexible and adaptive approach to aid delivery, completing our evolution away from technical blueprints

. This means more development strategies and programmes which address the political as well as technical barriers to development progress. As Alan Hudson points out, it also means creating the systems and processes which allow for more flexible and adaptive working – including better problem diagnosis; more innovative approaches to procurement and contracting; greater investment in monitoring, evaluation and learning; and new skills and capabilities for staff. Lastly, it means a fundamental change in organisational culture so staff are empowered and incentivised to think politically and work flexibly.Engage with elites and citizens to expand the policy space and support governance change . Development agencies will always be peripheral actors in bigger stories of governance change. But, rather than promoting our own institutional fixes, we can have more impact by supporting home-grown efforts to build consensus amongst elites, empower citizens and develop institutions that are both capable and legitimate. This work is not easy, but it can have potentially transformative results. DFID has a growing number of programmes working successfully in this way, including on extractive transparency in Nigeria, hydropower reform in Nepal, education reform in Pakistan, and service provision in Burma.

Tackle the international drivers of bad governance and promote new international norms . It

is clear that country-level governance dynamics are increasingly being shaped by cross border and transnational flows. Many of the biggest governance challenges of our time including corruption, tax evasion, illicit trade and violent extremism are global in nature. This demands a global response. Last year’s International Anti-Corruption Summit was a great example of how international action can be galvanised to address these threats – including through measures to strengthen transparency in the UK such as the new register of beneficial ownership. International initiatives like the Open Government Partnership and Extractives Industry Transparency Initiative also have an important role in promoting global norms on transparency and accountability, particularly given trends towards creeping authoritarianism and closing civil society space across the world.

is clear that country-level governance dynamics are increasingly being shaped by cross border and transnational flows. Many of the biggest governance challenges of our time including corruption, tax evasion, illicit trade and violent extremism are global in nature. This demands a global response. Last year’s International Anti-Corruption Summit was a great example of how international action can be galvanised to address these threats – including through measures to strengthen transparency in the UK such as the new register of beneficial ownership. International initiatives like the Open Government Partnership and Extractives Industry Transparency Initiative also have an important role in promoting global norms on transparency and accountability, particularly given trends towards creeping authoritarianism and closing civil society space across the world.In DFID we are taking forward work on several of these fronts. The UK Aid Strategy puts governance at the heart of HMG and international efforts to tackle the underlying causes of instability and poverty. Our new Economic Development Strategy, also being launched this week, goes even further in articulating the links between governance, growth and private sector development. DFID has long sought to understand the “drivers of change” in partner countries and put political economy analysis at the heart of our programmes in order to enhance impact. This has been combined with recent efforts to simplify and streamline our aid processes and create more space for flexible and adaptive programming. We are still on a learning curve and certainly would not claim to have all the answers, but the WDR offers a good opportunity for us to consider what more we could do improve practice on the ground and deliver better development results.

Stefan Kossoff is Head of Profession for Governance for the UK Department for International Development

January 29, 2017

Links I Liked

Fantastic news. John Ambler, one of the wisest heads in development, has written his memoirs/life lessons, free to  download

download

Simon Maxwell has written one of the most comprehensive reviews to date of How Change Happens, striking a nice balance between liking it and finding loads of gaps.

RCTs (Randomised Controlled Trials) came under scrutiny (again). First a study in the BMJ showed that large effects in small RCTs are rarely followed with larger RCTs to double check, but when they are, 43% fail to find an effect.

Then some CGD researchers took exception to Action Aid and Education International commissioning counter-research to their RCT on Charter Schools in Liberia. Are RCTs neutral and objective (so AA & EI are indulging in a ‘blanket dismissal of evidence’), or inherently flawed and/or biased (so some counterbalancing qualitative research is entirely sensible, and at $30k, a lot cheaper than an RCT)? Discuss.

And two comedic highlights of a pretty awful week.

A bad lip reading of the Presidential inauguration. Priceless

Not only are the Dutch setting up an international safe abortion fund to plug the $600m funding gap caused by reinstatement of the US “global gag rule” but they also produced the funniest spoof of the week. The Netherlands explains itself to the new US pres, in his own style. 14m hits and counting. Respect.

January 26, 2017

Reframing climate change: how carbon reduction can also reduce poverty and inequality

Given the events of 2016 we may well need to find additional ways of arguing for action on  climate change. Luckily, new evidence highlights additional incentives for action.

Ruth Mayne

explores the ‘co-benefits’ of tackling climate change and the practical benefits they can bring to community and national development.

climate change. Luckily, new evidence highlights additional incentives for action.

Ruth Mayne

explores the ‘co-benefits’ of tackling climate change and the practical benefits they can bring to community and national development.

We normally understand climate change as a collective action problem. The climate is a global public good which everyone benefits from. Therefore if one government/organisation/individual takes action everyone else benefits. But this can create an incentive for others to free ride on the efforts of others without having to incur any of the costs. Fortunately, mounting evidence about the economic, health, social and environment co-benefits of reducing carbon emissions challenges this understanding and may be one of the factors driving increased action by communities, municipalities, businesses and governments around the world.

Co-benefits A co-benefit is any additional benefit, other than carbon savings, derived from carbon reduction policies and programmes whether renewable energy generation , home energy, transport, food, agricultural, forestation etc.

Evidence about co-benefits is growing year on year. Stern was among the first to argue that the economic benefits of strong and early action (in terms of avoided damage from climate change) would outweigh the costs of action, and that delaying action would become much more expensive.  Recent studies by the International Energy Agency show multiple social, economic and health co-benefits from improved energy efficiency across a range of sectors and that fuel cost savings more than offset the additional investment costs of achieving a global warming below two degrees. The fifth IPCC report concludes that the benefits outweigh costs for demand-reduction measures in transport, buildings and industry. A recent study in the UK has shown that at national level the environmental and health co-benefits of the national carbon reduction activities recommended by the Committee on Climate Change would significantly outweigh the negative impacts. A review for DFID shows a range of co-benefits from low carbon electrification in southern countries and so on.

Recent studies by the International Energy Agency show multiple social, economic and health co-benefits from improved energy efficiency across a range of sectors and that fuel cost savings more than offset the additional investment costs of achieving a global warming below two degrees. The fifth IPCC report concludes that the benefits outweigh costs for demand-reduction measures in transport, buildings and industry. A recent study in the UK has shown that at national level the environmental and health co-benefits of the national carbon reduction activities recommended by the Committee on Climate Change would significantly outweigh the negative impacts. A review for DFID shows a range of co-benefits from low carbon electrification in southern countries and so on.

Opportunities

The implications are significant: where the value of co-benefits from carbon reduction outweighs the costs then it makes sense for governments and others to reduce carbon emissions irrespective of whether others do so or not. At international level the economic co-benefits mean that countries and business can gain early-mover advantage in international markets. As one business academic has pointed out ‘With many nations beginning to move on climate change, those that move first, second, third and so on are likely to reap the biggest gains. The global low carbon economy will be dominated by technical standard-setting processes that will cause profound restructuring of national economies. As most companies know it is better to be leader than a laggard in standard-setting processes’.

Within countries it means governments can leapfrog dirty polluting fossil fuel industries and reap a  range of co-benefits from reducing carbon emissions; national and local businesses can benefit from lucrative new job-creating markets; and local government and communities can use low carbon policies and finance incentives to simultaneously help tackle a range of other local economic, social and health strategic objectives. There will be losers in some sectors from the transition to a low carbon future which needs to be taken seriously and addressed. Strong social security systems and training can help workers through the transition and weaken threats by incumbent firms about job loss.

range of co-benefits from reducing carbon emissions; national and local businesses can benefit from lucrative new job-creating markets; and local government and communities can use low carbon policies and finance incentives to simultaneously help tackle a range of other local economic, social and health strategic objectives. There will be losers in some sectors from the transition to a low carbon future which needs to be taken seriously and addressed. Strong social security systems and training can help workers through the transition and weaken threats by incumbent firms about job loss.

Distributional implications

Interestingly, the distributional implications of co-benefits have been less discussed. Conventionally, national and international carbon reduction policies and programmes have tended to focus on getting the biggest emitters -whether rich countries or large institutions – to reduce and report on their carbon emissions. A strong case can also be made to get high emitting rich individuals to reduce their emissions. From a narrow carbon reduction perspective such an approach makes sense. Ethically, these actors make the biggest contribution to climate change and therefore should also bear the biggest burden in reducing emissions (as reflected in the principle of common but differentiated responsibility). Practically, they also have greater resources/capacity to take action.

But co-benefits also offer an opportunity to use carbon reduction policies and programmes to simultaneously help reduce poverty and inequality. They mean that as well as seeking to reduce the emissions of high emitting countries/organisations/individuals, carbon reduction policies and programmes also need to be designed so that they share co-benefits with lower emitting poorer countries/smaller organisations/low income individuals. Indeed failure to do so will mean that the co-benefits accrue to the better resourced, further exacerbating existing inequalities.

Internationally it is widely accepted in principle, if not always in practice, that the costs of carbon mitigation for poor countries should be subsidised e.g. through the transfer of low carbon technologies. Within the UK, it is widely accepted that low income households, even where they are low emitters, should receive subsidies and practical assistance to improve the energy efficiency of their homes because of the huge health benefits that warm, dry homes confer.

Not as contradictory as we thought?

The evidence of co-benefits linked to low carbon transport, food, clean energy and tree planting programmes suggests that the same inclusive design principles should be applied to these sectors too. This would imply targeting investment in low-cost low carbon public transport modes used by poor people; tackling barriers that prevent low income people from accessing low carbon, healthy, low meat/high plant diets; establishing community benefit renewable energy cooperatives in low income communities etc. More widely, it means targeting investment to economic sectors that can simultaneously reduce carbon emissions and create jobs/incomes for low income groups such as energy efficient homes.

Communicating climate change

Co-benefits also have implications for how we communicate about climate change. Efforts to motivate action on climate change have tended to focus on communicating the environmental and human impacts of climate change or our ethical responsibility to act for sake of the planet and future generations. These messages remain important. But highlighting how action on climate change can also contribute to fairer, healthier and more prosperous communities, and a more human economy, may well help convince those who are sceptical about purely ‘altruistic’ or ‘hair-shirt’ arguments.

January 25, 2017

Handy NGO Guide to Social Network Analysis

Social Network Analysis has been cropping up a bit in my mental in-tray. First there was my  Christmas reading – Social Physics, by Alex Pentland. Then came yesterday’s post from some networkers within Oxfam. So here are some additional thoughts, based on a great guide to SNA by the International Rescue Committee.

Christmas reading – Social Physics, by Alex Pentland. Then came yesterday’s post from some networkers within Oxfam. So here are some additional thoughts, based on a great guide to SNA by the International Rescue Committee.

Complexity and Systems Thinking seems to push people into two divergent sets of conclusions. One camp says ‘planning and toolkits suck, stick to close observation and response to any given context, and work from instinct, judgement and fast feedback’.

Another group cries ‘whoopee, a whole new set of toolkits!’ The problem with the first is how to ensure rigour and accountability, when everyone is just taking decisions according to their ‘instinct’ (what if someone’s instinct is disastrously wrong?) The problem with the second is that it can create exactly the kind of alluring but false certainty that complexity and systems approaches criticise elsewhere (logframes etc).

I lean towards the first group, with qualms, but like to keep an eye on the second, both to see if it is being oversold, and in the hope that it really does contain the seeds of a more rigorous approach to complexity. Social Network Analysis (SNA) looks like one of the most promising type 2 approaches. I’ve been worried that it is primarily being conceived as a tool for big guys with a lot of resources (see this post on Ben Ramalingam’s work, which prompted an impressive set of comments), so I was happy to come across the IRC’s excellent ‘SNA Handbook’, which provides a practical guide that seems well suited to NGO capacities.

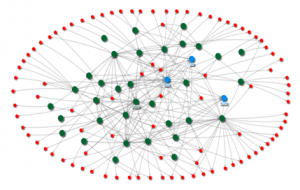

In 9 pages, the guide sets out how to run a relationship mapping exercise, how to examine the influence of the different network members over the issue that is being addressed (pretty much the same as Oxfam’s Power Analysis approach). It then gets on to how to analyze the network, with some examples from an SNA by IRC’s team in Sierra Leone.

‘To understand social networks it is not only important to analyze the relationships between actors, but to also consider their location within the network and the overall structure of the network. The following questions may help to analyze the structure of the network:

A) Are there any actors with a high number of connections?

B) Are there any actors that appear peripheral to the network?

C) How centralized or interconnected is the network?

D) Are there any fault lines between or separate parts of the network?

E) Are there any actors that link significant parts of the network together?

In trying to manage and mitigate risks the following are common issues to look out for in your network:

Examining the Influence of Network Members

Dependency: The network maybe highly dependent on a single actor or a funding source, which can create bottlenecks and sustainability concerns.

Dysfunctional / conflicting relationships: There may be certain key broken relationships which

impede the entire network. New actors or interventions can also introduce conflict for resources or control.

Marginalization: Certain actors or groups of people may be excluded or marginalized within the network, perhaps owing to gender, ethnicity, status, income or other factors. Analysis of the reasons behind the structure of the network may help to uncover the reasons for marginalization and how best to overcome it.

Disincentives for change: Certain actors may have disincentives to support the proposed change and may try to actively oppose it. Pay particular attention here to how the intervention would change resource flows or change the levels of influence of each actor.

Like-me relationships: You may notice that actors (people / groups) who share certain attributes, such as gender, age, education, ethnicity, religion, status, tend to have many ‘like-me’ relationships and fewer relationships with people different from themselves. This is a common pattern in many networks. It may be worth considering how this affects the specific issue and how to overcome it.

Structural challenges: Structural risks may include an overly centralized network or a structural split within the network.

The Sierra Leone team identified risks at the community level related to the disincentive of

Analyzing the Network

pharmacists, traditional healers and secret society heads to support community health workers, who represented a threat to their livelihoods and status.

In trying to capitalize on opportunities the following are common issues to look out for in your network:

Critical relationship building: There may be some very simple wins that you identify during development of the network map. For example, you might identify two actors who are positive and have influence, but these champions may not be connected. Facilitating relationship building between key actors may prove beneficial.

Tap into under-utilized support: You may identify actors within the network who are very positive about the change you seek to bring about, but who have not been given a role or sufficient voice within the proposed intervention. Give voice to these ‘champions’ and empower them to play a more central role.

Building networks within the network: There may be the potential for coalition building to raise the voice and influence of those who are positive about the proposed change. This can be done through more formal partnership arrangements or could be through organizing events to give a platform to those who share your ambitions.

The Sierra Leone team identified opportunities to build important relations between traditional and administrative leaders and health services providers to better coordinate support for community health workers.’

It then uses the SNA to think through possible scenarios:

‘SNA is useful for analyzing what the network looks like now. It can also be helpful for considering how it might change in the future. Participants may wish to consider how different scenarios would affect the network, for example:

What would the ideal network look like and how could this be brought about?

What would happen to the network if conflict were to resume?

What would happen to the network if funding ended or the IRC transitioned out?

If a funding source ends or key actor leaves, a functional network (A) can quickly break up (B). It is therefore a helpful to consider which relationships to invest in (C).’

Smart. Any other SNA tools that people can recommend for overstretched organizations on the ground?

And just because I recently watched it again, here is ecologist Eric Berlow talking (very fast) about the value of visualization in finding the ‘simplicity lies on the other side of complexity’, using my favourite complexity diagram – the Afghan military mind map, and lots of other stuff, all in 3 minutes.

January 24, 2017

What makes Networks tick? Learning from (a lot of) experience

When are networks the right response to a development challenge (as opposed to a monumental talking shop –

A network

more hot air than action)? Oxfamers Andrew Wells-Dang, Stéphanie de Chassy, Benoit Trudel, Jan Bouwman and Jacky Repila discuss:

Working with and as a part of networks is an inescapable part of today’s interconnected world – and increasingly of Oxfam’s programming and influencing. But what kinds and structures of networks are most effective at building social capital? How can networks bring desired benefits to their members and participants? How can they achieve positive impacts on governments and businesses? How can we ensure that the networks are inclusive and promote the rights of women and marginalized groups? And finally, how can INGOs and institutional donors support these platforms to contribute to change beyond limited project cycles?

Summarised below are the learning points distilled from a recent workshop:

A common purpose is the first requirement of a successful network. Whether collective action is conceived as networks, coalitions, alliances, or in other terms is immaterial; what matters is that the structure is consistent with the group’s mission and aims. Networks can be assessed using qualitative or quantitative means or a combination of the two. Workshop participants learned from examples of the Qualitative Assessment Scorecard (QAS) used in Vietnamese advocacy coalitions, Social Network Analysis (SNA) employed in Georgia and Armenia, and do-it-yourself network mapping from the Asia region’s GRAISEA programme. Each approach has strengths and limitations. Quantitative methodologies (such as SNA) analyse the number of links and connections amongst network members, but not their quality or change over time. Colourful and detailed network maps (produced using SNA as shown above) can be a useful conceptual tool, especially for large networks across multiple sectors or countries. Qualitative tools (such as the Scorecard) are important for shared reflection and self-assessment, offering a frame to interpret a network’s internal growth and contributions to change. However, these approaches are less effective for cross-network comparisons.

Different kinds of Network

Oxfam (and other international organisations) should critically assess our roles in networks. In some countries, INGOs are joint members of networks with local partner organisations, whilst in others, Oxfam plays a convening and co-funding role but does not consider itself a member. Both approaches are appropriate in the early stages of network formation, but should be reconsidered as networks move towards consolidation and sustainability. An evaluation of network weaving in Armenia and Georgia found that Oxfam and several other international members play an “anchoring” role in binding other members together: without the brokering and liaising of central network members, the alliances were at varying degrees of risk of fragmentation. Reducing the alliance’s vulnerability of implosion is all the more critical in the South Caucasus with the planned closure of Oxfam’s offices in 2018 and the need to leave a programme legacy for spin-off organisations Bridge in Georgia and OxYGen in Armenia. As a direct result of the evaluation findings, mitigation steps are being taken, including rotating leadership roles and strengthening local connections through capacity development and exchange visits between local network members.

Sustainability of networks is possible, but not a given and not always desirable. Some networks exist for a particular purpose: when their goal is achieved (or blocked), the members disband and move “underwater” until the next collective opportunity emerges. In other cases, informal social networks among activists persist for years without external support. Other networks develop increasingly formal organisational structures, with secretariats and dedicated staff. In all cases, sustainability is not just a question of funding: it depends on members’ commitment to a shared vision, their trust in each other, and sufficient (but not dominating) leadership capacities. It also depends on the capacity of a network to adapt to a dynamic and changing environment, review vision and strategies, and re-invent themselves beyond the project cycle.

Network building is a key influencing strategy, building on a broader process of Political Economy

Network of networks

Analysis (or power analysis). All programmes working with networks have undertaken forms of stakeholder and context analysis in the design and formulation periods. The ‘big questions’ that all networks must address are ‘WHAT is the change we want?’ and ‘WHY is this critical to people living in poverty?’ These processes have included consideration of gender justice, and in some cases ethnic and regional equity as features of power and influence in the respective contexts. Whether or not the context assessment is called by the technical name of political economy analysis, key to its success is the involvement of (potential) network members themselves in contributing their understanding of the situation in which they live and act. In this way, political economy analysis is not an academic exercise conducted by expert consultants, but is done on a frequent – even daily – basis by insiders who seek to interpret their own context. Outsiders and part-outsiders, like Oxfam advisors, can help to facilitate this process and serve as sympathetic critics and reviewers, building influencing capacity and setting benchmarks for change.

We boiled down conversations at the workshop, added what we’d already read and produced this handy (we hope) guide to what constitutes an effective network (watch this space for future learning resources):

Characteristics of effective and sustainable networks

Pre-existing social capital:

Networks that build on/evolve from existing relationships (rather than engineered or top down created networks)

Networks that have built up a shared history that creates mutual trust (or at least a good understanding of points in common and differences!)

Strategic fit

This includes the shared vision that network members have developed.

This is a crucial aspect in the early stages of network formation and will have a strong impact on its effectiveness. It often requires a big investment from the members.

It also entails the value addition the network brings to all members. What is the network’s relevance to its members?

Diversification of the value proposition (more entry points) makes the network stronger

Old Boys’ Network (can you spot David Cameron and Boris Johnson?)

Connectivity

The quality, mix, spread, inclusiveness of the relationships and connections in relation to the purpose of the network

Speak with one voice when it matters, developing a collective surge capacity

Leadership

Strong, non-hierarchical leadership that facilitates and fosters rather than top-down management

Leadership that is shared and distributed among members

Governance and management

Control is shared and all members can influence management decisions

Clear governance and management structures as well as well-defined rights and responsibilities of members

Agree what success looks like and how it will be measured

Mutual trust

Reciprocity – a mutual give and take that develops into trust

Openness and willingness to share and learn

Accountability

Members participate

Members are represented

Members are committed and have ownership

Organizational effectiveness

The network provides quality services

Has the necessary skills and capacities

Manages to tap into the capacity of its members (resources, time, talent)

Adaptability

Capacity to adapt to changing context and needs of the membership

Continuous learning and feedback loops

Dynamism

Joint learning

Commitment to learn together

If you want to be posted when more network assessment resources come on line, have your own experience to share, or you want to find out more about the work being done, contact Jacky Repila in the Oxfam GB Programme Learning Team.

This blog is based on discussions at two workshops hosted by Oxfam’s South Caucasus Food Security programme in Yerevan, Armenia on 13-15 December 2016. Watch this short video to hear from the participants themselves what they took away from the event.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers