Duncan Green's Blog, page 122

March 21, 2017

If we want to innovate, we need to disrupt our relationships and embrace tension

Guest post from

Caroline Cassidy, Communications Manager in  ODI’s Research and Policy in Development team

ODI’s Research and Policy in Development team

Henry Ford famously said ‘if you always do what you’ve always done, you’ll always get what you’ve always got.’ The same can be said for our relationships. When it comes to getting evidence into policy no one can dispute that to have any success you need strong working relationships, champions, and collaborators. But rather than moving forward, are we going round in circles by surrounding ourselves with liked-minded people? Do we curse tension, when really it keeps us on our toes? And do we shy away from our adversaries because it’s easier (and cheaper) not to engage?

I have been grappling with these questions since ODI’s recent event on evidence and decision-making in a complex world. The sheer importance of relationships for creating change was the central thread running through the day. But I agree with one participant who argued that we need to get better at ‘disrupting’ relationships to stop things getting stale. More importantly, we need to embrace tension in relationships and work with it, rather than against it, (as any therapist will tell you!).

We love being surrounded by like-minded people

We love being surrounded by like-minded people

Recent events in global politics have highlighted the various biases that influence our decisions. In our professional lives, as much as our personal, we tend to surround ourselves with those who are like us – it’s as old as the hills. We filter who we work with like a Google search, drawing on our values, experience and expertise. What’s more, research indicates that the more we surround ourselves with like-minded people, the more entrenched and even extreme we become in our beliefs. This can make it harder for innovation to happen. So how do you get past this?

There is no easy quick-fix. Exchanges and cross-sector events are just a few examples of spaces that can help create dialogue and expose us to different perspectives. Experimenting is key. Take the growth of transdisciplinary research, one example of how to bring together different ways of thinking and working. One such example is Earthquakes Without Frontiers, where natural and social scientists work together with policy and civil society actors, to build community resilience to earthquakes. All parties have different methodologies, approaches and interests and bringing these together is not easy. But it’s essential if there is to be any progress in unlocking the complexities of earthquake hazard and social resilience.

few examples of spaces that can help create dialogue and expose us to different perspectives. Experimenting is key. Take the growth of transdisciplinary research, one example of how to bring together different ways of thinking and working. One such example is Earthquakes Without Frontiers, where natural and social scientists work together with policy and civil society actors, to build community resilience to earthquakes. All parties have different methodologies, approaches and interests and bringing these together is not easy. But it’s essential if there is to be any progress in unlocking the complexities of earthquake hazard and social resilience.

Tension is not going away, and nor should it

At the same time, when it comes to tension, we are often looking for that wand to magic it all away. Donors and implementers, researchers and decision-makers, communications and research teams; some healthy tension is great (and is never going to go away!).

And nor should it. It’s this very push and pull that keeps both sides on their toes and can lead to conciliation, compromise and new perspectives.

Just this week I was talking to a research colleague about how we can improve a communication process based on a few issues that arose; the result is that we are trialling new techniques that we’ve never used before. We didn’t pretend to agree, but the only way out was to embrace our different interests, be transparent and find a path that was mutually beneficial.

We must seek out our adversaries and engage them

Policy-making, at all stages, is political. Working with adversaries may be challenging but it cannot be avoided, particularly for policy influence.

There’s one quadrant in this stakeholder mapping tool that identifies those who could be considered your ‘foes’. They are not aligned with your perspective, but have a high interest in the area you are working in. Using a tool like this can prioritise these types of actor and think about strategies to engage them.

File 1_AIIM

There is a wealth of literature out there on developing these types of strategy, but I quite like this toolkit, which goes as far as to use psychographics to really understand other parties. Rather than ‘poking’ someone with an opposing view, you can consider techniques to decrease or neutralise tension, whilst being realistic about what can change.

But none of the above is cheap, nor easy

Developing transdisciplinary programmes and projects, engaging with adversaries and taking the time to get to know how others work is expensive and time consuming. In many cases, it is a lot easier to plough on as before.

However, I think that things are changing. None of these challenges are new, but global politics is reminding us that we cannot continue as before. At a simple level, I think we need to be even bolder and take a hard look at events and fora so often filled with the usual suspects and recognize that overall, they aren’t taking us forward. And lest we forget, we need to assess what works and what doesn’t work in our relationships. The international development sector faces tough times and we must get smarter at how we work with tension, disrupt the status quo and ultimately innovate. But then you probably know that already…

March 20, 2017

Links I Liked

Either a genius subeditor placed this ad, or serendipity is a wonderful thing [h/t Mark Perkins]

Branko Milanovic at his brilliant best on why 20th Century tools cannot be used to address 21st Century income inequality, and what to do instead

Edible drones are a thing, apparently, or soon will be. 50kg of food and soon you’ll be able to eat the vehicle. Here’s the inedible version

Cash v Chickens. Chris Blattman v Bill Gates. What’s not to like?

Ten top tips for social scientists seeking to influence policy. Some good advice here

Useful discussion of likely next steps on proposed US aid cuts

Oh dear. The first meeting of the first “Girls Council” in Saudi Arabia [h/t  Rana Harbi]

Rana Harbi]

Chinese inequality is now falling.

As women in India get better educated and (a bit) wealthier, they stop going out to work.

What if it had been a woman being interviewed in South Korea? Wonderful satire on women, multi-tasking and a man with only one sock (wait for the end)

‘Reform for y’all’. Chinese state rap videos. Really. Not sure I can ever forgive Ranil Dissayanake for this link

March 17, 2017

How can governments raise money from automation and ICT to compensate the losers?

Got a feeling I’m going to end up looking pretty stupid with this post, but hey, what’s the point of a blog if you can’t  humiliate yourself in public?

humiliate yourself in public?

Went to a ‘digital development summit’ earlier this week (here’s a prior curtain raiser on this blog). The theme was the ‘future of work’ (see earlier musings on this blog). Proper post to follow when I have time to process the conversations, powerpoints and papers, but in a desperate attempt to justify my invitation, I raised the issue of digital taxation, and wanted to consult the FP2P hivemind on the idea.

The problem (or challenge as we prefer to call them): A range of ICT is threatening mass disruption of labour markets worldwide. This could be temporary (until new jobs are taken by retrained workers and/or new cohorts) or permanent (growing fears that new jobs will not be able to fill the gaps). In either case, there is interest in finding a source of revenue to compensate those whose jobs are automated out of existence. As in the argument over trade liberalization/globalization, how do we redistribute some of the earnings from winners to losers?

The added problem with ICT is that so much of it, from global outsourcing web platforms to freelancers, is particularly footloose. Traditional taxes on income or corporate profits are easy to evade and/or push companies to relocate to low tax jurisdictions. Are there any better options?

Time for a digital Robin Hood?

A digital Tobin Tax? A tiny tax per gigabyte of data transferred across the Internet, which could be used either for a Universal Basic Income (one idea that has come up repeatedly in terms of ‘the end of work’), or for other more targeted purposes. I realize that taxing a public good like information is pretty heretical, but even web inventor Tim Berners Lee is starting to question the current set up (though to be clear, he’s calling for more controls, not taxes).

A digital VAT: if automation, robots etc are adding the value, rather than human workers, is that an argument for a differentiated level of tax between standard VAT and the digital variety? Here’s one discussion I came across.

Robot tax: a proposal from Bill Gates that made headlines. It looks like a narrower form of the digital VAT. All sorts of problems defining what is/is not a robot (suspect Bill did not envisage laptops running Microsoft as candidates….).

Then there’s the related how change happens discussion. Whatever the technical (de)merits of particular approaches, lots of other factors will determine when/how they get picked up. Based on what happened to the Tobin Tax (30 years in the wilderness, cultivated by a small group of supporters, then coming in from the cold due to the global financial crisis, albeit rechristened as the Financial Transactions/Robin Hood Tax), here are some thoughts:

Someone needs to do the intellectual leg work on the feasibility of such proposals while they remain on the fringe

But nothing is going to happen until a major shock hits the system, eg a neo-luddite rebellion against the machines, or a massive scandal (a tech company sends in the courts/bailiffs to drag workers out of its factories/their cars). By comparison with the Global Financial Crisis, a shock that turns tech giants into anti-social pariahs in the eyes of the public and politicians would open the doors for new forms of taxation and regulation.

Whether that critical juncture leads to change depends on the intellectual preparation, but also the relationships and networks built up before the shock hits.

I’m sure all these proposals have massive drawbacks, and that there are lots of other ways of getting at the same end  (redistribution from the winners of ICT-based productivity rises to the losers). But the alternative is accepting a shrinking tax base, a steady decline in large areas of employment, and a bunch of under-funded and rather inadequate policy responses. Ball in your collective court.

(redistribution from the winners of ICT-based productivity rises to the losers). But the alternative is accepting a shrinking tax base, a steady decline in large areas of employment, and a bunch of under-funded and rather inadequate policy responses. Ball in your collective court.

I sent this draft over to Ben Ramalingam, one of the organizers of the conference, who kindly sent back these links for those who want to dig deeper (including me, once I’ve finished launching the book):

‘- The OECD has done some very comprehensive work in this area (chapters 7 & 8 are worth a scan).

– Worth also highlighting that in some developing countries the agenda is going in the opposite direction, with a tax on cash transactions to incentivise digital payments e.g Modi’s panel recommendations in India

– Some more on efforts to tax digital goods worldwide here, which highlights the challenge of getting a single approach / system

– The Economist had a nice piece on the Gates proposal which concluded that taxation is just one route, and in a highly interconnected world, not necessarily the most effective route, for sharing digital dividends.’

March 16, 2017

Ten Signs of an impending Global Land Rights Revolution

Exfamer

Chris Jochnick

, who now runs

Landesa

, the land rights NGO, sets out his stall ahead of a big World Bank  event next week.

event next week.

The development community has experienced various “revolutions” over the years – from microfinance to women’s rights, from the green revolution to sustainable development. Each of these awakenings has improved our understanding of the challenges we face; each has transformed the development landscape, mostly for the better.

We now see the beginnings of another, long-overdue, revolution: this one focused on the fundamental role of land in sustainable development. Land has often been at the root of revolutions, but the coming land revolution is not about overthrowing old orders. It is based on the basic fact that much of the world has never gotten around to legally documenting land rights. According to the World Bank, only 10% of land in rural Africa and 30% of land globally is documented. This gap is the cause of widespread chaos and dysfunction around the world.

There are in fact ten factors pushing land to the top of the global agenda:

1. Livelihoods and food security

The majority of people living in poverty today depend on land for their survival, but lack secure rights to it. That insecurity creates a powerful disincentive to invest, undermining efforts to boost farmer productivity and leaving hundreds of millions of small farmers permanently on the brink of survival. By contrast, secure rights can boost productivity by 60 percent and more than double family income. The UN 2030 Agenda (the Sustainable Development Goals) includes land rights in its first two goals covering poverty and hunger.

2. Sustainable Economic Growth

2. Sustainable Economic Growth

The so called Asian Tigers offer a powerful reminder that securing land rights for small farmers is a fundamental pre-condition for strong sustainable economic growth. A study of 33 countries found that stronger property rights were associated with a five percent increase in GDP growth and a global study of 108 countries found that stronger property rights were associated with an increased average annual growth of per capita income of 6 to 14 percentage points.

3. Women’s Empowerment

Today, more than half the world’s countries deny women the ability to own, inherit or manage land by law or custom. These barriers condemn women to second class status and poverty, generation after generation. While sixty percent of working women in sub-Saharan Africa are in the agricultural sector, they often work without secure legal or customary rights, accessing land only through a male relative. If they are widowed or have an argument with their brother or father, they and their children are likely to be left homeless and landless. There is arguably no single intervention as powerful as legally documenting, formalizing, and strengthening women’s land rights to transform a women’s status, voice and economic prospects Accordingly, the UN Sustainable Development Goals include land rights in the 5th goal covering gender equality; and a global campaign on women’s and girls’ empowerment launched by Women Deliver and dozens of INGOs fully embraces land rights.

4. Conflict and Human rights

The human rights community has put land rights on the map as land grabbing and attendant violence have captured national and global headlines. Growing conflict around ever-scarcer land is driven by population growth, climate change-induced desertification and flooding, and pressure in industrialized countries to find new sources of minerals, commodities and food in the Global South. In emerging economies, an estimated 93% of concessions granted to investors for extractive activities are already occupied by communities, setting the stage for widespread expropriation and violence. A study of civil conflicts since 1990 showed that land was at the root of the majority of them; and Global Witness declared 2015 the deadliest year for land defenders, with over three killed every week.

5. Governance and accountability

Land grabbing is one of the clearest symptom of governmental dysfunction. As Transparency International

highlights, it thrives where corruption is high and rule of law is low. The vast tracts of land that remain undocumented and the billion plus people living under insecure regimes stands as one of the greatest challenges to strong institutions and rule of law.

6. Indigenous Peoples’ Rights

Indigenous peoples have been fighting to protect their territory for thousands of years. Today, an estimated 2.5  billion people depend on indigenous and community lands. These lands cover over 50% of the planet, but only one fifth of that land has been formally recognized as legally belonging to the indigenous and local communities that occupy it. More than 500 organizations led by Oxfam, Rights Resources Initiative and the International Land Coalition are actively campaigning to secure the collective land rights of indigenous peoples and local communities.

billion people depend on indigenous and community lands. These lands cover over 50% of the planet, but only one fifth of that land has been formally recognized as legally belonging to the indigenous and local communities that occupy it. More than 500 organizations led by Oxfam, Rights Resources Initiative and the International Land Coalition are actively campaigning to secure the collective land rights of indigenous peoples and local communities.

7. Conservation and Climate Change

Stronger land rights are one of the most effective tools we have to ward off deforestation and climate change. A growing body of evidence underscores that secure land rights for forest communities are the best defense to forest destruction. Likewise, for individual farmers, the lack of long term horizons leads to slash and burn practices. Climate smart approaches to agriculture, including water and soil conservation, better seeds and fertilizer, planting of trees will only thrive where farmers feel they have a secure stake in the land.

8. Humanitarian crises and response

Insecure land rights leave vulnerable people facing natural disasters with strong incentives to stay in place, fearing that by evacuating they will lose any claim to their land. Lack of clear land tenure following crises also makes rebuilding nearly impossible, in large part because of unclear land rights.

As urbanization rapidly increases across the global south, city planners are stymied by a lack of clear land tenure, leading to illegal and unplanned urban sprawl, massive slums (an estimated 60-80% of African city dwellers lack secure property rights), conflict and forced evictions. The UN’s “New Urban Agenda” explicitly recognizes the importance of land rights, as does the seminal campaign to secure “land rights for all” launched by the world’s largest housing rights organization – Habitat for Humanity.

10. Peace, security and refugee flows

Struggles over land have spurred many of the most enduring and devastating wars and refugee flows of our times, including in places like Syria, Sudan, Rwanda, Colombia and Myanmar. Liberians fear their country is on the brink of civil war, yet again, and conflict over land is a driving factor. For national governments, insecure land rights may present an existential threat, whereas for the international community they are key to securing an enduring peace and stemming the flow of refugees.

It’s clear then why the development community is rallying around land rights – value for money it is tough to beat them. Stories of the importance of land rights and the many successful land interventions are daily fodder for mainstream and academic media (well-curated by Thomson Reuters here and Land Portal here). The business community has its reasons too – land rights are critical to sustainable supply chains and secure investments. Governments are also coming around. Next week, over a thousand land rights practitioners from civil society, business and governments will gather at the World Bank’s Annual Land and Poverty Conference. Momentum is building behind a land rights revolution.

March 15, 2017

The Power of Data: how new stats are changing our understanding of inequality

Every Saturday my colleague Max Lawson, who’s Oxfam’s global inequality policy lead, sends round an email  entitled ‘Some short reading for the weekend if you fancy it’. This week was particularly good, so I just lifted it:

entitled ‘Some short reading for the weekend if you fancy it’. This week was particularly good, so I just lifted it:

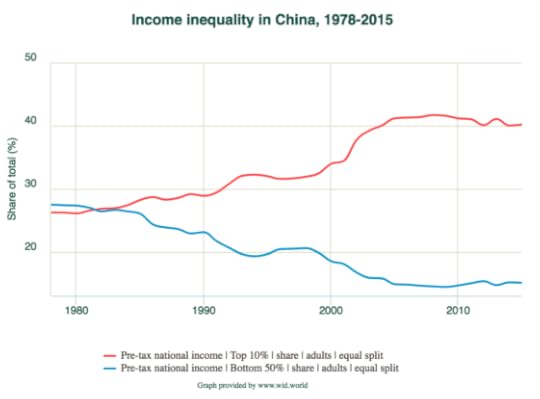

This year has already been good for the improvement in data availability on inequality, with the launch of the Wealth and Incomes Database (WID) in Paris in January. This database allows you to easily search for the data on top incomes gathered by Piketty and colleagues. Although limited in its country coverage, for those countries it does manage to cover it is fascinating. Take these two charts looking at the incomes of the top 1% and top 10% in contrast to the bottom 50% in China for example.

There is a good write up of the launch of the WID database here and you can access their excellent interactive database itself here.

There is a good write up of the launch of the WID database here and you can access their excellent interactive database itself here.

The WID database is based on the painstaking collection of tax records which has revolutionised our understanding of the scale of inequality. It has revealed that inequality is significantly worse than we thought. This is because the usual way to calculate the Gini is the household survey, and this is notoriously poor at capturing the rich- either they do not make it into the sample, or they do not fully report the scale of their wealth. Sadly the top incomes method, whilst very revealing, can’t really be used in the majority of developing countries as tax records are very poor and also the numbers paying personal income tax at all are very few.

A really great paper from Laurence Chandy and Brina Seidel this week, explores another new way of working out what top incomes really are, and correspondingly the real level of inequality. This Brookings paper uses a new method, identified by Branko Milanovic and Christoph Lakner, which instead compares household surveys with the national accounts of a country. The results are really dramatic – increases across the board and many other changes in country position:

‘The ten countries in the world with the highest Ginis include five new entries: Nigeria, Mexico, Indonesia, Georgia, and Guatemala. Whereas the U.S. (0.41) and China (0.40) report very similar levels of inequality, when we adjust for missing top incomes the U.S. appears considerably more unequal than its rival (0.51 versus 0.44). Meanwhile, India has the dubious honor of leapfrogging both countries under our adjustment, as its Gini skyrockets from 0.36 to 0.56.’

This final finding echoes other studies on India, who use consumption to calculate their Gini which is another reason it is very low. Officially their Gini is the same as Ireland, whereas it is probably closer to Brazil.

This final finding echoes other studies on India, who use consumption to calculate their Gini which is another reason it is very low. Officially their Gini is the same as Ireland, whereas it is probably closer to Brazil.

The rapid development of research and interest in ways of calculating inequality better is very exciting. There is no doubt that in the next few years we need to see a redoubling of efforts to collect more and better data to show us a clear picture of the scale of inequality in every country across the world, and more accurately plot trends too.

Finally in the UK two influential think tanks, the Institute for Fiscal Studies and the Resolution Foundation have just made projections that inequality is set to rise over the next few years, having remained relatively static and even falling slightly in recent years by some measures. The incomes of the poorest in particular are set to fall considerably which is deeply concerning, especially as the UK already has a million people regularly using food banks to survive. The chart below illustrates this very well.

This graph shows the power of good data, as you have in the UK (although here too better estimation of top incomes is needed).

This graph shows the power of good data, as you have in the UK (although here too better estimation of top incomes is needed).

The ultimate aim of the WID database it to produce Distributional National Accounts (DINA) to provide annual estimates of the distribution of income and wealth using concepts of income and wealth that are consistent with the macroeconomic national accounts. This would be a fantastic development and would revolutionise the way we appraise government policy and our economies. Oxfam is planning to work with others to launch a major call for better data on inequality this year.

March 14, 2017

Can economic growth really be decoupled from increased carbon emissions in Least Developed Countries? Ethiopia’s Story

These are definitely not the research findings I expected to be presenting. The data in front of me has challenged some of my long-held assumptions.

Climate negotiations through the years show us one thing very clearly – that Least Developed Countries demand the right to develop their own economies and build their own prosperity for their people. They are not prepared to accept underdevelopment under the guise of ‘carbon responsibility’.

So the question becomes whether Least Developed Countries can deliver these improved living standards for their citizens without causing the environmental damage historically inflicted through growth in the West…or to put it another way …Can LDCs “leapfrog” dirty technology and move straight to green solutions? Does prosperity always automatically come with a carbon price tag? Evidence of any form of “absolute” decoupling (where growth goes up and emissions go down) is very thin on the ground. “History provides little support for the plausibility of decoupling” says Tim Jackson in Prosperity Without Growth.

Well Tim, we now have early, tentative evidence that such “decoupling” is indeed possible in practice. This is Ethiopia’s story.

Ethiopia’s Commitment

Geothermal plant, Ethiopia

We all think we know about Ethiopia – the familiar headlines – famine, drought, refugees. Right now that old stereotype is back in the news: Ethiopia is in the midst of a severe drought crisis, and according to the latest figures, 5.6 million people need food and still more need water, Ironically this suffering is likely to be more severe because of climate change.

Ironic because Ethiopia is a big and complicated place, and other, remarkable, progress is being made, including on climate change: In 2010 Prime Minister Meles Zenawi committed Ethiopia to two amazing joint goals: To become a Middle Income nation by 2025 and to do this by 2030 without a single additional gram of Greenhouse Gas emissions (GHGs) from 2010 levels.

These commitments were set out in Ethiopia’s Climate Resilient Green Economy (CRGE) Strategy 2010. The context is not promising. One third of Ethiopia’s people currently live on less than $1.25 a day, so the strategy commits Ethiopia to raising real incomes per person 3.3 times over 15 years (measured by Gross National Income per capita). Also by the end of this target period there will be over half as many people again in the country. All without increasing emissions.

Surely this is madness – I thought as I flew into Addis Ababa in July 2016. For my research, I used World Bank statistics of Population, Gross National Income (GNI) and GHG emission, alongside CRGE commitments to calculate how much more carbon-efficient Ethiopia’s Technology would need to become to meet its targets.

Using World Bank figures on Population growth and Ethiopian commitments to Middle Income status and carbon neutrality it is possible to calculate that “Technology” in Ethiopia needs to become more carbon-efficient by a factor of over 4.5 times (2010- 2030) if CRGE goals are to be met.

I also compared this level of Technological (leapfrogging) carbon efficiency gains to that achieved by other nations at times of strong economic growth. Using the same methodology, between 1999 and 2012 none of the 6 other countries surveyed (2 OECD countries, 2 BRICS countries and 2 other developing countries) were able to rise to the challenge of decoupling on this scale.

So has Ethiopia got a track record of achievement to back up its ambitious commitments? Using the World Bank datasets I looked back at Ethiopia’s recent performance and also talked to key players in Government and civil society.

Here are the killer figures – Between 1999 and 2012:

Population increased 43%,

National affluence (GNI) increased 242%

But GHG emissions actually decreased by around 15% (see graph). After taking population growth into account, per capita emissions went down over 40%.

These results blew me away. They demonstrate that Ethiopia has the track record to meet their twin targets if they  can just stay on the same trajectory.

can just stay on the same trajectory.

How has Ethiopia achieved this? …by making its institutions ready for change. The study looked in depth at the capacity of Ethiopia to benefit from climate finance and then focused in on some landmark case studies in investment into “green growth” initiatives – the rollout of a national programme of “Eco Industrial Parks”, securing international private investment in construction of a major geothermal plant and ongoing efforts to enhance the take-up of “New Improved Cook Stoves” across the country.

Conclusion

So where has all of this got us? Ethiopia’s achievements may constitute a small, tentative, fragile message of hope. If we believe World Bank figures, at very early stage development Ethiopia has decoupled absolute GHG emissions from economic growth.

Critical questions remain: fruitful areas for new research. In particular – How have the benefits of this green economic growth been distributed among the people? If growth can indeed be green and the results of growth be equitably shared to relieve poverty, then we really have a development model which is worth replicating. “Win-win” solutions for the planet and the people.

Perhaps it will prove harder to sustain once low hanging fruit and easy wins have been banked….or just possibly Ethiopia has forged a new route for Sustainable Development – a model for other LDCs to follow.

The study was undertaken in partnership with Oxfam GB, the Environment & Climate Research Centre in Addis Ababa, UNDP’s Ethiopia office and the University of Birmingham.

For more information/detail please contact Steve on stephen_baines@sky.com

And here he is presenting the research in more detail.

March 13, 2017

Links I Liked

Current refugee numbers are high, but certainly not unprecedented, and a small fraction of total global migration.

Current refugee numbers are high, but certainly not unprecedented, and a small fraction of total global migration.

Honduran farmers sue World Bank private lending arm over human rights violations. I went there in 2012 and the palm oil sector is indeed a grim place.

Why does the Gates 2017 letter ignore ‘behaviour’, ‘politics’ and ‘institutions’? asks Suvojit Chattopadhyay

Nice summary of research and debates on the Universal Basic  Income, especially in India, by Justin Sandefur, including this lovely graph from Laurence Chandy and Christine Zhang: Foreign aid is now twice the cost of ending world poverty (subject to the big if of getting the $ directly into the hands of poor people).

Income, especially in India, by Justin Sandefur, including this lovely graph from Laurence Chandy and Christine Zhang: Foreign aid is now twice the cost of ending world poverty (subject to the big if of getting the $ directly into the hands of poor people).

OECD book on applying Behavioural Economics to policy (aka nudge units): 129 cases from 14 countries. Interesting, but still feels very top down/paternalist (how do we get poor people to do what we think is best for them?)

And an International Women’s Day medley: Best (Iceland) & worst (S  Korea) places in for working women in the OECD. The Economist’s Glass Ceiling Index for International Women’s Day

Korea) places in for working women in the OECD. The Economist’s Glass Ceiling Index for International Women’s Day

Unstoppable/Women Unlimited. Powerful 1 minute Oxfam soundtrack to International Women’s Day

And finally what happens when the ‘invisible’ care economy erupts on camera? Millions of hits and instant fame, that’s what. Apparently, the stressed woman is not the nanny, but interviewee Robert Kelly’s wife, Jung-a Kim (in case you were worrying about her job prospects). Both kids are awesome, and Dad recovers well from a bad start (attempted facepalm of his daughter – not good).

March 9, 2017

A masterclass on cash transfers and how to use High Level Panels to influence Policy

One of the things I do in my day-a-week role at LSE is bring in guest lecturers from different aid and development  organizations to add a whiff of real life to the student diet of theory and academia. One of the best is Owen Barder, who recently delivered a mesmerizing talk on cash transfers and the theory of change used by his organization, the Center for Global Development, which is one of the most effective think tanks around (although I don’t always share its politics….). Here’s the summary (and here are his powerpoint slides, if you want to nick them).

organizations to add a whiff of real life to the student diet of theory and academia. One of the best is Owen Barder, who recently delivered a mesmerizing talk on cash transfers and the theory of change used by his organization, the Center for Global Development, which is one of the most effective think tanks around (although I don’t always share its politics….). Here’s the summary (and here are his powerpoint slides, if you want to nick them).

Owen chaired a recent high level panel on humanitarian cash transfers and presented its work in his talk. The traditional aid response is ‘people are hungry due to drought, flood, conflict etc → there isn’t enough food → we need to ship in loads of food’. Both arrows are wrong: Amartya Sen showed that the problem in famine is not lack of food, but lack of purchasing power among the affected populations – in nearly all of Ethiopia’s famines, the country has produced enough food to feed its people. The second arrow is wrong because giving people cash is usually a much more effective response than shipping food over from the US or wherever: the food often arrives too late, just when local farmers are recovering, and a flood of free food promptly destroys local markets. The evidence is now substantial:

Cash transfers are 25-30% cheaper than in kind aid (so more food per dollar)

When people are given in kind aid, they typically sell 30-50% of it to get the cash they need, at roughly 30% of the actual cost of the aid – a massive level of waste

When you ask refugees, they invariably say cash is better than stuff (eg 80% of Syrian refugees in Lebanon)

Plus it’s good politics – cash stimulates the local economy, so local people are less resentful of the influx of refugees, and is more respectful – refugees don’t all want the same thing; cash respects their right to make decisions about their lives.

Nothing new there – Sen proposed cash transfers in his 1981 book, Poverty and Famines. So why then is only 6% of humanitarian aid currently given over to cash and vouchers (and the majority of that to vouchers, not cash – we just don’t have disaggregated numbers)? As always when good stuff is being blocked, it’s a combination of interests, ideas and institutions:

Interests: US and European farmers and shipping companies lobby ferociously to prevent cash replacing their lucrative contracts. Owen on US food aid: ‘it’s a scandal, people should be prosecuted’.

Ideas: donor countries think poor people make bad spending decisions – better to give them food instead. More recent concerns over money ending up in the hands of terrorist groups

Institutions: Parts of the UN system in particular exist solely to distribute food aid, but lots of other players, including big international NGOs, are also part of the system.

Institutions: Parts of the UN system in particular exist solely to distribute food aid, but lots of other players, including big international NGOs, are also part of the system.

According to Owen, ‘almost every big change worth pursuing looks like this’ in terms of blockers. ‘Don’t think you’re going to go ahead and change the world just because you have a better idea’. So what’s CGD’s theory of change?

Nail down the evidence (yes, even in these post-truth times, that matters)

Power analysis: who makes the decisions that count? In this case about 7 large donors, not the UN; win them over and the rest of the system will fall into line

Build an influential network through a High Level Panel

Owen is something of a connoisseur of high level panels and reckons there is a particular way to making them effective:

Start with what you think is the right answer

Be prepared to learn and adapt that answer to improve the concept and proposal, benefitting from diversity of ideas

Invest time and energy in finding the best language to communicate the idea, including ‘specific, actionable recommendations’ and an elevator pitch that may actually have to be delivered in an elevator at international meetings (you listening, WDR?)

Build credibility with policy makers, eg by doing public polling to show your proposal has support, or getting it into important international documents and agreements (as CGD did with the World Humanitarian Summit)

A High Level Panel creates a team of ambassadors for your idea, so make sure they come from the different communities you are trying to influence.

Some other aspects of CGD’s theory of change are more subtle:

if you can show that transforming the existing system on X opens up new opportunities to address problems on Y, then you have a bunch of potential new allies (eg cash transfers will reduce duplication between aid agencies).

It concentrates on fixing systems rather than filling gaps

Rather than just calling for more aid, it focuses on how to make existing aid go further

CGD and the Panel decided against setting an arbitrary target (eg 25% of humanitarian aid should be CTs) and opted for recommending a process instead as a way to change behaviours: they proposed that a small group of donors should take the plunge and call for tenders for a single unified, unrestricted CT payment for a particular humanitarian situation. If the bids turned out to be cheaper/more efficient than the traditional approach, then boom!

And now they have it: DFID and ECHO (the EU’s humanitarian wing) put out an $85m bid for CTs to Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Because of ECHO procurement rules the bid is open only to the UN system, which has been slow to switch to CTs – sweet. It’s caused a big fuss, but is the UN really going to turn down $85m? Watch this space.

And here’s the 4m animated summary

March 8, 2017

I just found a place where smart people take time to discuss books and ideas, and then you can walk in the snow

Spoke at my first literary festival this week – ‘Words by the Water’ in Keswick. I’ve no idea if it was representative of  other such events, but it was fascinating. About 100 people showed up to hear me bang on about How Change Happens. They were probably the most un-aid wonk audience I’ve spoken to so far; they were also the oldest – the demographic at the whole festival was overwhelmingly retired and probably one of the cleverest.

other such events, but it was fascinating. About 100 people showed up to hear me bang on about How Change Happens. They were probably the most un-aid wonk audience I’ve spoken to so far; they were also the oldest – the demographic at the whole festival was overwhelmingly retired and probably one of the cleverest.

If you’re speaking to an audience of pensioners, things are a bit different. Firstly, quite a few of them go to sleep. Best not to take it personally (hey, I dozed through a couple of talks myself), but keeping going with the powerpoint when a guy in the front row is out cold, head thrown back, mouth open, and being elbowed by his embarrassed wife, is definitely a skill worth acquiring.

But when they’re awake they are as sharp as anything – Q&A included ‘is your use of systems based on hard systems or soft systems methodologies’, to which my reply was ‘eh?’ They are also (thankfully) bookish – How Change Happens sold out, as did many other authors.

The thoughtful, erudite conversations continued in the cafe on the margins of the festival – got into one exchange with a retired environmental scientist on whether entropy and evolution are contradictory laws (entropy = increasing disorder; evolution = increasing order).

The thoughtful, erudite conversations continued in the cafe on the margins of the festival – got into one exchange with a retired environmental scientist on whether entropy and evolution are contradictory laws (entropy = increasing disorder; evolution = increasing order).

Then there were the other authors. I actually found the non-fiction sessions more interesting, including lots of people who resembled famous faces off the telly, only greyer (a bit like watching the House of Lords).

Which got me thinking again about the role of older people in society. Here is this huge repository of the smart and experienced. They may have decided to get off the frantic merry-go-round of full time work (I have a friend who retired as a General Practitioner because at 60, he just couldn’t hit his target of seeing a new patient every 12 minutes); they may not be able to keep up with the endlessly receding IT frontier; but surely there are ways to tap into all that wisdom?

In advocacy, I have long thought that older people make better lobbyists (more contacts, more experience, more credibility, greater staying power) – hence my so-far-failed attempts to get Oxfam and others interested in ‘grey panthers’ lobby groups. At LSE, where I teach one day a week, one of the main roles can best be described as mentoring – listening to students’ interests and doubts, suggesting paths to take and things to read. A lot of the people at this festival would be great at that, but how to set it up?

That does of course assume older people would want to stay in touch in this way. They seem to be having a pretty  good time anyway, if Keswick is anything to go by.

good time anyway, if Keswick is anything to go by.

So if any other litfest organizers are looking for speakers, let me know – especially if your event is somewhere as beautiful as the Lake District. I have to confess that I bunked off to go hill walking most days. The highlight was climbing a hill/mountain called Blencathra, (here’s me crunching through the snow), then descending in time to hear a film maker and poet introduce the lyrical film of the same name. Wonderful day.

March 7, 2017

What do we know about when data does/doesn’t influence policy?

Josh Powell, Chief Strategy Officer at the Development Gateway weighs in on the Data and Development debate

While development actors are now creating more data than ever, examples of impactful use are anecdotal and scant. Put bluntly, despite this supply-side push for more data, we are far from realizing an evidence-based utopia filled with data-driven decisions.

One of the key shortcomings of our work on development data has been failing to develop realistic models for how data can fit into existing institutional policy/program processes. The political economy – institutional structures, individual (dis)incentives, policy constraints – of data use in government and development agencies remains largely unknown to “data people” like me, who work on creating tools and methods for using development data.

One of the key shortcomings of our work on development data has been failing to develop realistic models for how data can fit into existing institutional policy/program processes. The political economy – institutional structures, individual (dis)incentives, policy constraints – of data use in government and development agencies remains largely unknown to “data people” like me, who work on creating tools and methods for using development data.

We’ve documented several preconditions for getting data to be used, which could be thought of in a cycle:

While broadly helpful, I think we also need more specific theories of change (ToCs) to guide data initiatives in  different institutional contexts. Borrowing from a host of theories on systems thinking and adaptive learning, I gave this a try with a simple 2×2 model. The x-axis can be thought of as the level of institutional buy-in, while the y-axis reflects whether available data suggest a (reasonably) “clear” policy approach. Different data strategies are likely to be effective in each of these four quadrants.

different institutional contexts. Borrowing from a host of theories on systems thinking and adaptive learning, I gave this a try with a simple 2×2 model. The x-axis can be thought of as the level of institutional buy-in, while the y-axis reflects whether available data suggest a (reasonably) “clear” policy approach. Different data strategies are likely to be effective in each of these four quadrants.

So what does this look like in the real world? Let’s tackle these with some examples we’ve come across:

Top-Right (Command and Control): In Tanzania and elsewhere, there is a growing trend of performance-based programs (results-based financing or payment by results) that use standard indicators to drive budget allocations. In Tanzania, this includes the health sector basket fund and a large World Bank results-based financing program. Note that this process of “indicator selection => indicator performance => budget allocation” provides a clear relationship between data and policy outcome, lending itself to a top-down approach (well-characterized by a Tanzania government official, who told me that “people do what you inspect, not what you expect”). Where fixed policies and actionable data are present, this command and control approach makes sense – but be careful before trying to move this approach to another quadrant.

Top-Right (Command and Control): In Tanzania and elsewhere, there is a growing trend of performance-based programs (results-based financing or payment by results) that use standard indicators to drive budget allocations. In Tanzania, this includes the health sector basket fund and a large World Bank results-based financing program. Note that this process of “indicator selection => indicator performance => budget allocation” provides a clear relationship between data and policy outcome, lending itself to a top-down approach (well-characterized by a Tanzania government official, who told me that “people do what you inspect, not what you expect”). Where fixed policies and actionable data are present, this command and control approach makes sense – but be careful before trying to move this approach to another quadrant.

Positive Deviance (bottom-left): Here relationships between data and policy are much less clear, and neither lends itself to action. So why not drill down and find what is already emerging/working on the ground (positive deviance)? (i) Identifying high-performing districts, (ii) studying factors (both internal and external) that differ from the norm, then (iii) developing specific theories of change and (iv) using peer learning or other dissemination methods to test and learn from these “outliers”.

Name and Shame (top-left): Where evidence-based policy options exist, but actors are either unaware or unwilling to adapt, good old-fashioned naming and shaming can work wonders. We saw this in Ghana: a District Health Director presented local (high) maternal mortality rates to the District Assembly, which rapidly led to an increase of health worker coverage and engagement with community education groups. When we spoke to the director recently, she reported that district maternal mortality rates had been cut in half over a 2-year period (of course, many factors may have contributed to this). Naming and shaming can be a powerful motivator when data suggest clear policy changes, but can be otherwise difficult to replicate.

Analyze and Define (bottom-right): Here, relevant decision-makers are keen to solve a problem, but data may not provide a clear-cut solution. Here’s where the “elbow grease” approach of exploratory analysis and comparison of inputs (e.g. aid allocation) and outcomes (e.g. poverty) comes in. As an example, Nepal’s Ministry of Finance struggled with planning its investments and use of external resources, and was frustrated by the transaction costs of working with 30+ development partners. Using data from its Aid Management Platform, the government did its own analysis to create a development cooperation policy, outlining the “rules of the game” for development partners in Nepal. Exploratory data analysis for policy should be accompanied with an adaptive policy mindset: perceived relationships within data may end up being blind alleys, requiring flexibility to test and change when theories are disproven.

Analyze and Define (bottom-right): Here, relevant decision-makers are keen to solve a problem, but data may not provide a clear-cut solution. Here’s where the “elbow grease” approach of exploratory analysis and comparison of inputs (e.g. aid allocation) and outcomes (e.g. poverty) comes in. As an example, Nepal’s Ministry of Finance struggled with planning its investments and use of external resources, and was frustrated by the transaction costs of working with 30+ development partners. Using data from its Aid Management Platform, the government did its own analysis to create a development cooperation policy, outlining the “rules of the game” for development partners in Nepal. Exploratory data analysis for policy should be accompanied with an adaptive policy mindset: perceived relationships within data may end up being blind alleys, requiring flexibility to test and change when theories are disproven.

So what? Putting some ToCs to the test

At Development Gateway, our Results Data Initiative is working with country governments and development agencies, using a PDIA approach. At country level, we’re convening quarterly inter-ministerial steering committees (authorizers/problem holders) to identify problems or decisions for which they want to use data, and technical committees (testers/problem solvers) to identify ways to use data to get at these issues. We plan to work only with the government’s existing data sources– to learn what they can (and cannot) do with what they’ve got. Throughout this program, we’ll be applying these ToCs, and will report back on what we learn. I know we’re not the only ones thinking about this, and would love to hear what others have done to use data to influence development programming.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers