Duncan Green's Blog, page 132

October 24, 2016

The Politics of Measuring Inequality: What gets left out and why?

Two posts on the measurement of inequality this week, so you’ll need to activate the brain cells. First up Oxfam researcher  Franziska Mager

summarizes a paper co-authored with Deborah Hardoon for a panel at the recent Development Studies Association conference on the power and politics behind the statistics. A version of this post appeared on Oxfam’s shiny new real geek blog.

Franziska Mager

summarizes a paper co-authored with Deborah Hardoon for a panel at the recent Development Studies Association conference on the power and politics behind the statistics. A version of this post appeared on Oxfam’s shiny new real geek blog.

Inequality is a touchy issue, so for different actors, measurement is vital. We saw that when Oxfam published its Davos statistic on extreme wealth in February.

There is no one ‘right’ way to measure anything. That’s what measurement is: one way to quantify out of many. But there can of course be a wrong way – what we would say in statistics was inaccurate, with a bias and led us to a false conclusion, or something excessively imprecise. Plenty of statisticians and fact checkers work to identify when measures are wrong.

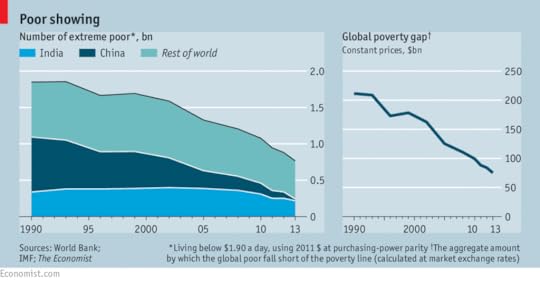

Right v Wrong is one important distinction. Another is ‘who is measuring what and why?’ Inequality of opportunity and inequalities based on forms of discrimination such as gender have long been an issue of concern in international development. Inequality of economic outcomes, however, has not traditionally been a priority, notwithstanding a concern for poverty reduction in absolute terms. This is due to an unwavering acceptance of the need for growth to fuel development and a belief in meritocracy. Globally, the extreme poverty line is fixed at $ 1.90 a day, which frames thinking around meeting an absolute level of basic needs and doesn’t consider the unequal spread of incomes.

Economic inequality can’t by captured by a single metric. For starters, income has different meanings, like market incomes and those after redistributive policies (taxes, benefits). They can lie far apart – Sweden is a good example  for high market income inequality but very low income inequality after redistributive policies. Not just that, within any definition of income, there are multiple ways to cut your data. You can calculate the Gini coefficient; use the Palma index or an analogous ratio relating different income groups to each other. The point is: different measures place different emphasis on different parts of the income distribution. Oxfam for instance advocate for measures that contrast the tails of the distribution better than the Gini.

for high market income inequality but very low income inequality after redistributive policies. Not just that, within any definition of income, there are multiple ways to cut your data. You can calculate the Gini coefficient; use the Palma index or an analogous ratio relating different income groups to each other. The point is: different measures place different emphasis on different parts of the income distribution. Oxfam for instance advocate for measures that contrast the tails of the distribution better than the Gini.

Beyond incomes, the extent of inequality within an economy is also expressed by wages, data on which can again be cut differently. In one such cut, wages tell us about the dispersion of earnings between those at the top and those at the bottom in a company or country – like CEO pay and minimum wages. But we can also analyse how much income is generated by wages compared to capital (e.g. returns on shares) – the latter by definition being an income source of the wealthy. Wages contain vital information about how an economy rewards workers and the link between labour and prosperity.

Analysing the wealth distribution in turn tells us who owns what assets. Wealth inequality is even more extreme than incomes and again reveals a different story about an economy – for instance one’s ability to react to shocks or exert power and influence.

Let’s look at some income examples where different measures tell different stories.

Brazil is one success story: over the past decade the incomes of the poor have been growing faster than those of the rich, poverty has been falling, and inequality by most relative measures along with it. The red bar shows the real incomes of the bottom 40% of the population. This bar represents the story of the poor getting better off, because although small, it almost doubles in size between 2004 and 2014. The blue bar is the richest 10% of income earners. Their incomes have also been increasing – but because they were high to begin with, this percent growth rate is  lower than that of the poor. This leaves the green bar: the ‘money difference’ between both. In those absolute terms, the richest are pulling away from the bottom (this is true of multiple data sources).

lower than that of the poor. This leaves the green bar: the ‘money difference’ between both. In those absolute terms, the richest are pulling away from the bottom (this is true of multiple data sources).

Using the famous elephant graph, differences concealed by rates of income growth and how this plays out on the global scale are eloquently explained tomorrow in our colleague Muheed’s post.

Now let’s think about Uganda. In this case, the choice of data source makes a bigger difference than the choice of indicator. Below we compare the Gini coefficient with the Palma ratio, the Gini being an estimate of inequality across the whole of the income distribution, whilst the Palma explicitly compares the richest 10% to the bottom 40%. As you can see, no matter the indicator, the inequality trend is roughly the same.

When we did this, we were startled by how patchy data is. World Bank estimates use consumption data (what people spend money on, rather than their incomes) and are based on household surveys conducted every few years. The last survey in 2012 calculated a Gini coefficient of 42 (the red line). In contrast, the data collected by the Ugandan Bureau of statistics estimated the Gini at 39.5 in 2012/13 – in inequality terms, a big difference. There are many more examples where a data source or indicator can change an estimate. And that’s the point: inequality measures are estimates. They’re never just true.

When we did this, we were startled by how patchy data is. World Bank estimates use consumption data (what people spend money on, rather than their incomes) and are based on household surveys conducted every few years. The last survey in 2012 calculated a Gini coefficient of 42 (the red line). In contrast, the data collected by the Ugandan Bureau of statistics estimated the Gini at 39.5 in 2012/13 – in inequality terms, a big difference. There are many more examples where a data source or indicator can change an estimate. And that’s the point: inequality measures are estimates. They’re never just true.

So who emphasizes what, and why?

An example is UN Sustainable Development Goal 10: to reduce inequality within countries. The indicator proposed is the growth of the incomes of the bottom 40% compared with the average. When incomes of the bottom 40% grow father than the average, the incomes of the poorest catch up with the average and relative inequality falls. Last year the World Bank found that the bottom 40% needed to see their incomes grow by at least 2% faster than the average in order to eliminate poverty by 2030 as per data collected by the Bank.

The emphasis on the lifting of the poor sounds good, doesn’t it? But the indicator doesn’t include any measure of the gains made at the top of the distribution. The measure also ignores starting levels of inequality, not distinguishing between high and low (initial) inequality countries.

Again, no measure in and of itself is the right one. We might call attention to these details because of Oxfam preferences, and not because of objective shortcomings. Rather, all measures are entangled with specific narratives. Why are we so enslaved to the Gini index as opposed to more intuitive measures? Do we care to know about the absolute distance that separates us from the top? How do we advance the struggle to better capture the top tail of the distribution?

There is nothing false about any measurement facet. Rather, recognising what is behind indicators, both in terms of data and the intentions of the communicator is essential to understanding both the economics of inequality and the politics of it.

October 23, 2016

Links I Liked

The value of history (h/t Luciano Floridi)

Does China’s rise really reframe how the rest of the world sees Western ideas (and ideals)? Brilliant Branko Milanovic piece

What makes young people more excited about politics? Deciding how to spend municipal budgets. So participatory budgeting = best way to reengage disenchanted millennials.

Migrants from developing countries sent home $439bn in 2015 (3 times the global aid budget). That’s slightly less than in 2014, but the World Bank expects a return to growth in 2016.

It’s UK publication week for How Change Happens. Big thanks to Amy Moran for this funky and frenetic ad for the book (and for designing its cool new website)

Backgrounder to Poland’s inspiring, citizen-led defeat of a terrible anti-abortion law

The amount needed to bring all the world’s poor up to the poverty line is now down to $78bn a year, 0.1% of global GDP

Don’t worry, it will be over soon. Saturday Night Live does the second and third US presidential debates. Classics to enjoy if/when politics turn sane again

October 20, 2016

Sen, Fukuyama, Chambers, Byanyima, Agarwal, Rodrik, Kumar and Robinson on How Change Happens

A week to go til the official How Change Happens publication day (a pretty artificial date, but apparently it helps with chasing up reviews), so time for another book-related post. One of the most heart-warming experiences for any author is when you send off your manuscript to a sprinkling of the great and good, and to your delight and astonishment, some of them send back a nice endorsement. Feast your eyes on this lot:

“In this powerfully argued book, Duncan Green shows how we can make major changes in our unequal and unjust world by concerted action, taking full note of the economic and social mechanisms, including established institutions, that sustain the existing order. If self-confidence is important for the effective agency of deprived communities, so is a reasoned understanding of the difficult barriers that must be faced and overcome. This is a splendid treatise on how to change the actual world — in reality, not just in our dreams.”

world by concerted action, taking full note of the economic and social mechanisms, including established institutions, that sustain the existing order. If self-confidence is important for the effective agency of deprived communities, so is a reasoned understanding of the difficult barriers that must be faced and overcome. This is a splendid treatise on how to change the actual world — in reality, not just in our dreams.”

In How Change Happens, Duncan Green points to a simple truth: that positive social change requires power, and hence attention on the part of reformers to politics and the institutions within which power is exercised. It is an indispensable guide for activists and change-makers everywhere.

In How Change Happens, Duncan Green points to a simple truth: that positive social change requires power, and hence attention on the part of reformers to politics and the institutions within which power is exercised. It is an indispensable guide for activists and change-makers everywhere.

It was George Orwell who wrote that “The best books… are those that tell you what you know already.” Well in Duncan’s book How Change Happens I have found something better: A book that made me think differently about  something I have been doing for my entire life.

something I have been doing for my entire life.

He has captured so much in these pages, drawing on global and national and local change and examples from past and present. But what makes this book so insightful is that at all times we are able to see the world through Duncan’s watchful eyes: From his time as a backpacker in South America to lobbying the WTO in Seattle and his many years with Oxfam, this is someone who has always been watching and always been reflecting.

Duncan has given us a remarkable tour de force, wide-ranging, readable, combining theory and practice, and drawing on his extensive reading and rich and varied experience. How Change Happens is a wonderful gift to all development professionals and citizens who want to make our world a better place. Only after reading and reflecting have I been able to see how badly we have needed this book. It does more than fill a gap. The evidence, examples, analysis, insights and ideas for action are a quiet but compelling call for reflection on errors and omissions in one’s own mindset and practice. It is as relevant and important for South as North, for funders as activists, for governments as NGOs, for transnational corporations as campaigning citizens. We are all in this together. How Change Happens should stand the test of time. It is a landmark, a must read book to return to again and again to inform and inspire reflection and action. I know no other book like it.

This is a gem of a book. Lucidly written and disarmingly frank, it distils the author’s decades of experience in global  development practice to share what can work and what may not, in changing power relations and complex systems. Again and again I found myself agreeing with him. All of us—practitioners and academics—who want a better world, and are willing to work for it, must read this book.

development practice to share what can work and what may not, in changing power relations and complex systems. Again and again I found myself agreeing with him. All of us—practitioners and academics—who want a better world, and are willing to work for it, must read this book.

This fascinating book should be on the bedside of any activist – and many others besides. Duncan Green is the rare global activist who can explain in clear yet analytical language what it takes to make change happen. Ranging widely from Lake Titicaca in Peru to rural Tajikistan, from shanty towns to the halls of power, this is a book sprinkled with wisdom and insight on every page.

How Change Happens is a positive guide to activists. When one feels despondent and disheartened then reading this  book will help to encourage, energise and inspire one to participate in the creation of a better world. Duncan Green makes the case with vivid examples that significant changes have taken place and continue to take place when social and environmental activists employ skilful means and multiple strategies such as advocacy, campaigning, organising and building movements. It is a wonderful book. Read it and be enthused to join in the journey of change.

book will help to encourage, energise and inspire one to participate in the creation of a better world. Duncan Green makes the case with vivid examples that significant changes have taken place and continue to take place when social and environmental activists employ skilful means and multiple strategies such as advocacy, campaigning, organising and building movements. It is a wonderful book. Read it and be enthused to join in the journey of change.

The world committed to global transformative change in 2015, with the 2030 Agenda and targets in the Paris Climate Agreement to stay well below 2°C and achieve carbon neutrality by the second half of the century. We need to understand how change happens in order to accelerate our pathway to a safe future. Duncan Green’s book is a timely and badly needed guide to bringing about the necessary social and political change.

Now I must wait in trepidation to see if the reviews agree, but that’s another post.

October 19, 2016

The Sidekick Manifesto – count me in

October 18, 2016

Why/how should corporates defend civil society space? Good new paper + case studies

I saw some effective academic-NGO cooperation last week, and even better, it involved some of my LSE students.

The occasion was the launch of Beyond Integrity: Exploring the role of business in preserving civil society space, commissioned and published by the Charities Aid Foundation and written by Silky Agrawal, Brooks Reed and Riya Saxena, three of last year’s LSE Masters students. They researched and wrote the report as part of a student consultancy project, and CAF were so impressed that they decided to publish it. Result.

First the content: the authors went looking for cases where businesses had got involved in defending civil society from attacks by government, and identified four really interesting cases (see table). They interviewed a number of the players in each case.

They found some ‘key learnings’ (bit depressing to see them already adopting the barbarisms of aidspeak!):

They found some ‘key learnings’ (bit depressing to see them already adopting the barbarisms of aidspeak!):

Firms in consumer-facing industries are responsive to large-scale social movements that raise awareness regarding human rights abuses;

Privately owned companies with strong ethics and values tied into the core business model, led by engaged leaders, are likely to respond to civil society;

At times, privately held dialogues between key stakeholders and host governments can be more effective at initiating positive action than a public challenge, as the respect and dignity of each stakeholder is maintained;

Leveraging formal and informal cross-sectoral networks is instrumental in convincing corporations to act on behalf of civil society.

The ensuing panel discussion was excellent (even though I was chairing it). Big cheeses from industry, the Clinton Administration (Bill, not Hillary), UN and Human Rights discussed the report – if only all LSE students got this kind of recognition before they’ve even graduated……

Some points that emerged:

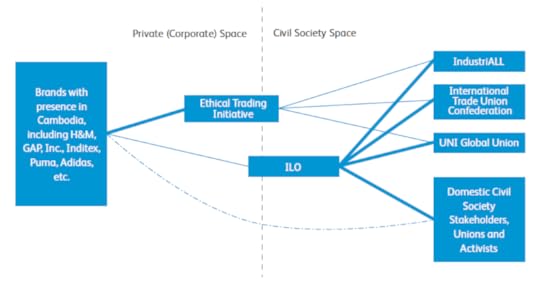

The importance of individuals and organizations that bridge the corporate and civil society spheres. In Cambodia the Ethical Trading Initiative and ILO played the role, but in Angola Brian Leber, CEO of an ethical jewellery company, took the lead

An interesting discussion on the bigger spread in behaviours among private firms – they can be ethical leaders (like Brian Leber’s company), or they can be corporate villains devoid of the restraints or accountability imposed on public companies.

Companies, just like NGOs, suffer from institutional amnesia, as staff turn over and no-one remembers that useful contact they had in the Indonesian trade union movement ten years ago. Long term partnerships can help retain access to those networks even when people move on.

A nice 2×2 on the range of corporate interest and action.

A nice 2×2 on the range of corporate interest and action.

The business case for acting to defend civil society space varies according to the sector and country, but overall, human rights defenders act as a form of unpaid due diligence for companies, keeping them alert to risks emerging within the system. So it makes sense to defend them.

However, company agency is difficult and can easily backfire into nationalist accusations of foreign meddling. Legitimacy is an issue for company activism as for any other player – corporations are not primarily accountable to local citizens or governments (except through the law). An issue will be more legitimate if it directly affects core company operations (staff, shareholders, brand, communities where they operate). ‘Companies should not become political campaigners – they should keep a clear link to their operations’. Eg Anglo American was able to lobby hard on the South African’s denial of the HIV pandemic in South Africa because 25% of its workers were HIV-positive.

Due to their big investments and royalties, extractive companies often have more access to government than, say, consumer goods companies, but their higher fixed investments also undermines their ability to take action – if you’ve sunk $2bn into an oil well, you’re at a disadvantage (but if you’re about to, you’ve got a good bargaining hand).

Multi stakeholder approaches help with legitimacy (by involving local actors, not just foreigners) and so can dilute the risk to the company of taking unilateral action. Yet the M-S approach seems barely to have spread beyond extractives (EITI) and consumer goods (ETI again). What about construction? Banks? Electronics?

I was left wanting more on at least three fronts:

Why no government interviewees? Would have loved to hear what sympathisers within government made of corporate activism

I would love to see a typology of contexts, governments etc that suggests when companies should

Act alone v collectively

Act in public v a private word in the government’s ear

Call on the company’s home country government to take action

Reactive v Proactive – all four cases are reactive – companies taking action when something bad happens, eg to defend a human rights defender from attack. Is that because they are more visible, or because that’s the only realistic approach? Any chance to get them engaged on e.g. legal challenges to restrictive new CSO laws?

Silky (S.Agrawal13@lse.ac.uk), Brooks (B.Reed@lse.ac.uk) and Riya (R.Saxena4@lse.ac.uk) are all graduating and available for hire – you could do worse!

October 17, 2016

Ha-Joon Chang on How Change Happens

October is upon us, and with it the publication of How Change Happens on the 27th. I am already suffering about my levels of authorial self-obsession: I entered the personal shorthand of ‘Narcissistic Peak’ for launch day, unaware that my diary synchs with my wife’s Ipad. Cathy hasn’t let me forget it.

levels of authorial self-obsession: I entered the personal shorthand of ‘Narcissistic Peak’ for launch day, unaware that my diary synchs with my wife’s Ipad. Cathy hasn’t let me forget it.

But given the surprising results of my precautionary poll (90% of voters not yet turned off by all the plugs for the book – I guess the others have already voted with their feet/mice), I am going to put up a series of book-related posts over the next few weeks (unless the voting needle starts moving violently in the opposite direction).

First up, the only time I cried during the writing was when I read Ha-Joon Chang’s foreword on my phone, while on holiday. I had just sent off the manuscript and was exhausted, but Ha-Joon’s kind words went a long way to redeem all the self doubt and hard work:

‘The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways. The point, however, is to change it’, said Karl Marx in one of his most celebrated passages, which eventually became one of his two epitaphs (the other one being, ‘Workers of all lands, unite’).

Marx was certainly right to argue that social theories should be not just about understanding the status quo but also about offering a vision for its improvement; but he was wrong to imply that no one before him had thought like that.

For the last several thousand years at least, human beings have tried to imagine a different world from the one they live in, and worked together to create it. Human history is littered with countless visions of—and struggles for—an alternative social order. These may have been large-scale social experiments based on elaborate theories, like Marxism, the welfare state, or neo-liberalism. Or they may have involved daily struggles for survival, safety, and dignity by oppressed and underprivileged people, even though they may not have had any sophisticated theory about their alternative world. However, the capacity to imagine an alternative social order and cooperating to create it is what distinguishes humankind from other animals.

Despite the fact that much of human history has been about attempting to create different realities, we do not understand the process of social change very well.

Despite the fact that much of human history has been about attempting to create different realities, we do not understand the process of social change very well.

To be sure, we have grand historical narratives that describe social change as the results of interactions between technological forces and economic institutions, such as property rights; Marxism is the best example of this. We know quite a bit about the way in which society is transformed because of the changes in political-legal institutions, such as the court system or international trade agreements. We have interesting and detailed accounts of how certain individuals and groups— whether they are political leaders, business leaders, trade unions, or grassroots groups—have succeeded in realizing visions that initially few others thought realistic.

However, we do not yet have a good theory of how all these different elements work together to generate social change. To put it a bit more dramatically, if someone wanted to know how she could change certain aspects of the community, nation, or the world she lives in, she would be hard pressed to find a decent guidebook.

Into this gap steps Duncan Green, the veteran campaigner for development and social justice, with How Change Happens, an innovative and thrilling field guide to—let’s not mince words—changing the world.

Many conventional discussions of how change happens focus either on technology (mobile phones can bring the revolution!) or a brutal account of realpolitik—how oligarchs and elites carve up the world. While not ignoring such factors, How Change Happens develops a far better framework for understanding social change by focusing on power analysis and systemic understanding; this is called the ‘power and systems approach’.

The power and systems approach emphasizes that, in order to generate social change, we first need to understand how power is distributed and can be re-distributed between and within social groups: the emancipation of women; the spread of human rights; the power of poor people when they get organized; the shifting power relationships behind the negotiations around the international economic system. While emphasizing the role of power struggles, the book does not see them as voluntaristic clashes of raw forces, in which whoever has more arms, money, or votes wins. It tries to situate those power struggles within complex systems that are continuously changing in unpredictable ways, affecting and being affected by diverse factors like social norms, negotiations, campaigns, lobbying, and leadership.

Providing a theory of social change that is convincing is already a tall order, but Duncan Green sets himself an even higher bar. The book aims to be a practical field guide to social activism. More than that, it aspires to be a field guide not just for the kinds of people he normally works with, such as NGO campaigners or grassroots organizers. It is meant to be a field manual for activists in the broadest sense: politicians, civil servants, businesspeople, even academics.

This is certainly a hugely ambitious project; how can anyone write a book that can provide sophisticated theories of social change, while providing practical advice to activists?

However, amazingly, How Change Happens delivers on its promise. Those who are purely interested in understanding better how societies change will find a treasure trove of theoretical insights and empirical evidence. Those who want to change the world through formal politics will certainly learn a lot from the book in terms of how to establish political consensus and legitimacy, how to build coalitions, and how to use national and international laws to initiate and consolidate changes. Civil servants who want to make things better for citizens, or business leaders who want to do more than simply maximize profits will also find plenty of lessons to draw from the book in devising policies and corporate strategies that can make the world a better place in realistic but innovative ways. The book will even help academics, like myself, who try to engage with real-world issues, to grasp better the role that their research and outreach activities can play in bringing about (or hindering) social change.

Drawing on his impressive knowledge of the relevant areas of the social sciences, his thirty-five years of diverse experience in international development and many first-hand examples from the global experience of Oxfam, one of the world’s largest social justice NGOs, Duncan Green has produced a unique and uniquely useful book addressing a hugely important but largely neglected issue. Everyone who is interested in making the world a better place should thank him for it.’

October 16, 2016

Links I Liked

‘and don’t criticise what you can’t understand’. Miche Doherty got there first…..

‘and don’t criticise what you can’t understand’. Miche Doherty got there first…..

The UN’s new, top secret, irony working group splashed big last week. After rejecting all seven of the qualified female candidates for Secretary General, the UN has chosen Wonder Woman as an honorary ambassador for the empowerment of women and girls. [h/t Kate Cronin-Furman]

My How Change Happens launch tour (aka ‘From Poverty to Powerpoint’) rolls on: this week Warwick, SOAS and Newcastle; next week Oxford, Sheffield, LSE and Edinburgh. That’s a lot of station sandwiches.

In 2001, only 15 international borders were fenced or walled off. Now there are 63 border fences on four continents. 3 part Washington Post video series.

The IMF is actually two institutions, according to the Guardian’s Larry Elliott. Its Research Department has broken with the Washington consensus, but the programme teams are still in the 1990s. Jekyll? Hyde? Can never remember which is which.

Getting there on Robin Hood? “EU financial transaction tax to be unveiled this year” [h/t Jon Slater]

The most dangerous moment in a kleptocracy (South Sudan, Yemen) is when it slides into insolvency. So why advocate for it, asks Alex de Waal?

Surrounded by piles of trash in the Macedonian city of Tetovo (one of the most polluted in Europe), two classical musicians protested by playing Bach. Classy and memorable protest.

October 13, 2016

On World Food Day, 5 reasons why cash transfers aren’t always the best option

Since the Asian Tsunami of 2004, providing cash to people in an emergency has become increasingly mainstream.  But (babies, bath water) there is more to food response than ‘just give them the money.’ On World Food Day, Oxfam

Social Protection Adviser

Larissa Pelham sets out the case:

But (babies, bath water) there is more to food response than ‘just give them the money.’ On World Food Day, Oxfam

Social Protection Adviser

Larissa Pelham sets out the case:

The King asked The Queen, and The Queen asked The Dairymaid: “Could we have some butter for The Royal slice of bread?”

The Dairymaid She curtsied, And went and told The Alderney: “Don’t forget the butter for The Royal slice of bread.”

The Dairymaid She curtsied, And went and told The Alderney: “Don’t forget the butter for The Royal slice of bread.”

The Alderney Said sleepily: “You’d better tell His Majesty That many people nowadays Like marmalade Instead.

Children’s writer AA Milne manages to muse cheerfully on most of life’s trials and tribulations in his writing and he’s hit the nail on the head again with this one. We’ve become so incredibly partial to ‘marmalade’ – cash – to help people access food in a crisis these days, that suggesting alternatives in response to recent emergencies can face push back even from within our own organisations.

Here are five reasons why cash isn’t a panacea.

Sometimes food is what people need and it can be ‘market friendly’, last week’s Hurricane Matthew which has affected 1.4 million people, being a poignant example. Homes, store cupboards and cooking equipment are buried, roads to markets are inaccessible and where Oxfam is working, there are initial reports of near total destruction of crops and livestock. People need a good meal inside them now so they can keep going. So Oxfam is trying to set up local kitchens to provide warm meals to people run by female ‘restauratrices’, this provides food, helps the labour market to recover and targets women. It’s simple, basic and essential.

The markets for households to purchase food aren’t always there, and don’t always bounce back as quickly as we

Undernourishment, 1990-2015 (source: FAO)

think/hope: Our own aid practices might have stifled them entirely, government policies and politicking may be silencing them, the lack of other vital markets like transport and fuel availability can be a hindrance or it can be too risky for traders to operate, particularly in conflict settings, as the ongoing crisis in South Sudan shows. And even if they are there, that ‘invisible hand’ is not always benign for the poorest purchasers: in the Malawi crisis back in 2002 traders hoarded to artificially inflate prices.

Unsurprisingly, cash alone isn’t enough. Long term social protection programmes (i.e. welfare, for those that don’t think that’s a dirty word) in developing contexts, recognised this a number of years ago. It’s what you do with your cash – and some people are better at using their cash than others. And so they decided on ‘’cash plus’. Give people cash plus a few other things besides such as training in different skills to improve their job opportunities, or seeds and tools or business planning and then they can really ‘maximise’ what they do with the cash. Well established programmes such as Ethiopia’s Food Security Programme have been doing this for years, combining a safety net with building household assets. The humanitarian sector is just catching up with this. And as OPM’s research is exploring, we humanitarians must get better at using existing schemes, rather than building costly, unsustainable systems from scratch.

And of course, prevention is better than cure – we all know that but the humanitarian sector is the most stubborn of leopards. We should be acting early with a range of appropriate interventions instead of distributing cash to resolve the problem afterwards. This doesn’t fit with donors’ planning processes, the competing demands for media attention, or the public’s responsiveness to pictures of utter destitution, but that’s where the re-focus needs to happen, so that we have the resources to avert crises in the first place.

And finally, like the King’s desire for butter, there’s no accounting for taste, whatever the current trend. We’re not all utility maximisers in a neat economics equation. We’re all different and not necessarily predictable. It’s what happens around the family dinner table, or underneath the makeshift tarpaulin, well behind closed ‘doors’, that is what really matters about individuals’ consumption. And that’s something we need to find out. Maybe too, some people just prefer food – particularly women: they can have more control over food and there can be less risk of abuse or assault than with cash although evidence to date is inconclusive. This means that marmalade isn’t necessarily best for us, or what we all want all of the time.

And finally, like the King’s desire for butter, there’s no accounting for taste, whatever the current trend. We’re not all utility maximisers in a neat economics equation. We’re all different and not necessarily predictable. It’s what happens around the family dinner table, or underneath the makeshift tarpaulin, well behind closed ‘doors’, that is what really matters about individuals’ consumption. And that’s something we need to find out. Maybe too, some people just prefer food – particularly women: they can have more control over food and there can be less risk of abuse or assault than with cash although evidence to date is inconclusive. This means that marmalade isn’t necessarily best for us, or what we all want all of the time.

Sometimes a little bit of butter is OK.

The Queen took The butter And brought it to His Majesty; The King said, “Butter, eh?” And bounced out of bed.

“Nobody,” he said, As he kissed her Tenderly, “Nobody,” he said, As he slid down the banisters,

“Nobody, My darling, Could call me A fussy man – BUT I do like a little bit of butter to my bread!”

October 12, 2016

How can we make Disasters Dull? Book review

Oxfam Senior Humanitarian Policy Adviser Debbie Hillier can barely contain her excitement – today is International Day for Disaster Reduction. To celebrate, she reviews a new book on the issue

for Disaster Reduction. To celebrate, she reviews a new book on the issue

While policy frameworks on Disaster Risk Reduction have proliferated – the SDGs, the Paris Agreement, the Sendai Framework – the practicality remains elusive.

This is the issue addressed by Dull Disasters? How Planning ahead will make a difference, by Daniel J Clarke and Stefan Dercon. Its simple thesis is that governments need to plan for disasters before they happen. Their plans must spell out what the risks are; in insurance-speak, this is called working out your contingent liabilities. The plan must also define who is going to pay for and be responsible for the response, the clean-up.

The book explains very well that if there is no plan, then the response is fragmented and inefficient and there are serious disincentives for people to prepare properly for disasters. Why should local governments/national governments/farmers invest and work hard to reduce their risk, if they may get bailed out by others in the event of a crisis?

The plan must be rules-based, ideally with automatic triggers leading to action, and hence not open to political manipulation. And the plan must be prefinanced. The book rails against ‘begging-bowl financing’: “This ad-hoc post disaster model for financing disasters is hardly worthy of the twenty-first century. In fact, it feels distinctly medieval.” I couldn’t agree more. Why would a local or national government take time and care to prepare a serious disaster plan if it is not clear whether there will be any funding for it?

The plan must be rules-based, ideally with automatic triggers leading to action, and hence not open to political manipulation. And the plan must be prefinanced. The book rails against ‘begging-bowl financing’: “This ad-hoc post disaster model for financing disasters is hardly worthy of the twenty-first century. In fact, it feels distinctly medieval.” I couldn’t agree more. Why would a local or national government take time and care to prepare a serious disaster plan if it is not clear whether there will be any funding for it?

What is striking is how few examples of this there actually are. The book keeps coming back to two which are surely ripe for imitation.

Mexico’s Natural Disaster Fund, FONDEN, which finances ‘build back better’ reconstruction costs of state infrastructure; this is funded by an annual budget allocation and reinsurance and a ‘catastrophe bond’ for the really big disasters.

Kenya’s Hunger Safety Net Programme, one of my personal favourites, which was specifically designed to scale up. It provides regular cash transfers for poor pastoralists in northern Kenya, and then quickly and efficiently provides cash to extra households in times of drought – there is really useful learning on this. In vulnerable countries, developing programmes – health, social protection, nutrition – that can scale up and down in response to the changing context is surely a big part of the answer.

Insurance is mentioned quite a lot in the book, but the jury is out on its effectiveness. One fact that struck me was that over the last decade, donors have supported over 100 pilot micro-insurance programmes for farmers – yet all have failed without subsidies. And whilst government-level insurance has a role to play, this seems to me to be far from any kind of gamechanger – even if the African Risk Capacity scheme had paid out in response to Malawi’s drought this year (which it didn’t, to much surprise and embarrassment), its maximum payout would have been $30m, whereas actual needs are $395m.

This book is certainly timely – disaster losses average $250-$300bn a year, with untold human suffering. It is  probably best suited to those already in the sector – perhaps government officials who need to implement those policy commitments – as it feels a bit like a text book. More real examples – successful or otherwise – would have made it more interesting and powerful.

probably best suited to those already in the sector – perhaps government officials who need to implement those policy commitments – as it feels a bit like a text book. More real examples – successful or otherwise – would have made it more interesting and powerful.

The book is right of course that planning ahead for disasters is crucial. Whilst being exhorted to think like an insurance company doesn’t really work as motivation for me, I hope it does work for governments. It also fits into the current narrative around ‘local humanitarian leadership’ which was a big takeaway from the World Humanitarian Summit in May. Instead of the international system riding in on its metaphorical white charger, local actors (both government and civil society) should be empowered and supported to lead a response that is explicitly driven by local needs and realities. This book shows that a government that wants to lead a disaster response well, needs to have done its homework first.

A PDF of the book is free to download

October 11, 2016

Is Advocacy becoming too professional? A conversation with World Vision and Save the Children

I was guest ranter at an illuminating recent discussion on advocacy with Save the Children and World Vision. They were reviewing the lessons of their ‘global campaigning on the MDG framework’ on maternal and child health (MCH) (here’s a powerpoint summary of their findings global-campaigning-within-the-mdg-framework-sci-wvi). Some of the conclusions were painfully familiar (quotes from the briefing for the meeting):

I was guest ranter at an illuminating recent discussion on advocacy with Save the Children and World Vision. They were reviewing the lessons of their ‘global campaigning on the MDG framework’ on maternal and child health (MCH) (here’s a powerpoint summary of their findings global-campaigning-within-the-mdg-framework-sci-wvi). Some of the conclusions were painfully familiar (quotes from the briefing for the meeting):

‘There is little evidence that global institutions’ monitoring and accountability are driving a more consistent implementation of commitments at a country level and whether civil society are consistently utilizing these promises as part of their campaigning’

But the conclusion from that observation set my alarm bells ringing:

‘Lessons learned:

There needs to be more coordination and planning together to ensure a meaningful contribution of CSOs to global reporting

There needs to be a clearer articulation in strategies of how global frameworks support national level change with specific activities to support partners, local communities and civil society to use intelligence in their campaigning

We need to understand how CSOs can better contribute to the global accountability frameworks and translate this into meaningful change at a country level.’

My conclusion was more like ‘oops, start again’ and I set out what I meant: Set aside your precious campaign and

At the cuddlier end of influencing

advocacy toolkits and go back to square one. How does change happen on MCH? What role is there for national organizations, including but not confined to CSOs? What role for voluntary international agreements like the MDGs, or for INGOs?

Which echoed my main finding on the paper I’m struggling to finish on theories of change on empowerment and accountability in fragile and conflict affected states: most organizations in aid and development don’t actually have a theory of change; they have a theory of (their own) action, which absorbs all their time and energy, leaving precious little space for thinking about how the broader system is evolving. Hardly surprising then that our theories of action tend to be pretty crude – they aren’t adapted to the system they are trying to influence. Paraphrasing Donella Meadows, advocates are more interested in dancing with each other than with the system.

But as the meeting wore on, my concerns got deeper. It felt like what I was witnessing was the birth of a new guild – the advocacy professional. There’s lots of reasons why that is a good thing – people learn from each other, exchange ideas and experience, and sharpen up their act. But I was also acutely conscious of the downsides. Any emerging guild has to establish its identities and boundaries – who is/is not a member. That rapidly leads to rituals of inclusion/exclusion, typically around language and methods, and the occasional burning of heretics just to keep everyone on their toes. Something similar is going on in the fledgling psychotherapy profession at the moment and it’s not a pretty sight.

Didn’t follow best practice, apparently

But that need to establish an Us/Them division of the world feeds into precisely the problem I was witnessing on theory of change v action – indeed it could be seen as its underlying cause. And it gets compounded when people think professionalizing means moving from ‘art’ to ‘science’ and then equate science with a bunch of set rules that they must follow.

What to do? In these situations, institutional logic tends to trump other kinds (like evidence for example): just look at the limited success of all the efforts to encourage academics to work across disciplines. In aid and development, the equivalent is pleas to abandon ‘siloed thinking’, but one person’s silo is another person’s epistemic community and future career. Who do you think is going to win that one?

What might help aid agencies and NGOs overcome this tendency? Some thoughts, but I’d welcome yours:

Internal secondments: make would-be advocates spend a month in other parts of the organization, and a few months with partners, to keep the ‘othering’ process in check

Money talks: funders can nudge people out of their silos (although academics’ dogged refusal to cooperate with other disciplines despite research funds being available shows the limits to that approach)

Other suggestions?

Some other highlights of the discussion:`

Campaigns tend to focus on new policy and budget commitments at national level. They are much less successful at getting such changes implemented, or at working on a sub-national level. Where campaigns have got somewhere on implementation, it is because advocates and programme people have joined forces.

Efforts to shoehorn different national contexts into a single set of global indicators suck (designed to allow INGOs to dazzle funders with ‘we saved X million kids last year’): ‘people running around collecting data that didn’t help them  much.’

much.’

Being an implementing partner with authoritarian governments is a double edged sword. On the one hand it engenders a good deal of caution and self censorship among INGOs; on the other, you have a reservoir of trust and access for ‘insider’ approaches that less engaged NGOs lack.

One of the problems for those trying to capture the results of advocacy is that staff on the ground don’t see what they do as advocacy – it’s just how you deal with the obstacles you face and the conversations you have to get your work done.

Save is trying to take these lessons on board in what looks like a very promising new ‘Global Accountability Framework’ for its global campaign that involves

Ditching global indicators

Focus on what you have learned/changed during the time of the programme

Develop ways of collecting data on how much learning has taken place

Use of impact stories and ‘ranking scales’

Moving to realtime data and feedback, for example getting staff to record activities on Google Maps

Working with some of their funders to develop ways to measure ‘political will’. Good luck with that

Developing ways to track public attitude changes towards maternal and child health

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers