Duncan Green's Blog, page 137

August 2, 2016

What explains advocacy success in setting global agendas? Comparing Tobacco v Alcohol and four other Global Advocacy Efforts

Oxfam researcher/evaluation adviser Uwe Gneiting introduces a new set of case studies

It’s an age-old puzzle – why do some advocacy and campaigning efforts manage to influence the political agendas of governments, international institutions and corporations but others don’t? What explains the difference in attention, resource mobilization and policy traction of some issues (e.g. anti-Apartheid, HIV/AIDS) compared to others (e.g. the limited success of gun control advocacy in the U.S.)?

The technical response to these questions is that it’s an evidence problem – issues gain traction if there is sufficient evidence regarding their severity, cause and an effective solution. But as has been discussed elsewhere (including on this blog), focusing on evidence alone neglects the role of power and politics in explaining which issues gain attention and policy traction and which ones don’t.

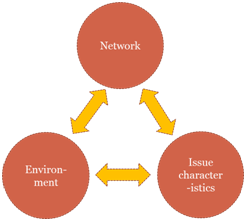

This was why a group of researchers (including me) recently published a set of studies that put forward a more nuanced explanation for the variation in advocacy effectiveness. The way we approached the task was to analyze and compare pairs of issues (we focused on global health) of similar types and harm levels but varying attention (newborn vs maternal mortality, pneumonia vs tuberculosis, and alcohol vs tobacco). We ended up with ten factors across three categories that in conjunction help to explain varying levels of advocacy success (see table below)

Network and actor features

Policy environment

Issue characteristics

Leadership

Governance

Composition

Framing strategies

Allies and opponents

Funding

Norms

Severity

Tractability

Affected groups

The set of case studies including a more thorough explanation of the explanatory factors can be accessed here. Here are my top three takeaways for advocates and researchers:

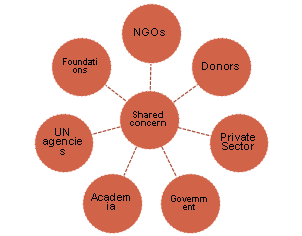

Think of networks (not campaigns) as vehicles for change

The first takeaway concerns our unit of analysis for analyzing advocacy effectiveness. It’s a common approach to analyze the most visible moments and actors (i.e. campaigns or individual campaign organizations) as the basic unit of analysis. We found that it is more useful to look at the wider webs of individuals and organizations sharing a concern for an issue that underpin these visible moments and their outcomes and thus enable effective advocacy. These networks nowadays exist around most global issues. Some are clearly civil society dominated; others resemble multi-stakeholder initiatives including broad participation by government institutions and the private sector. Some serve as information exchange and are loosely organized; others operate more like a single advocacy machine and are governed by a formal umbrella organization.

And we found that they matter – they shape global agendas by providing vehicles for sustained and collective action, highlighting the neglect and severity of a problem, shaping the understanding of it, advancing potential solutions, and influencing powerful actors to take up the issue.

The secret of effective advocacy networks – overcoming the trade-off between cohesive framing and broad-based coalitions

The second takeaway is that while these networks matter, not all of them are successful. This is because they are only one of several factors influencing global issue attention and prioritization. Comparing the successful with the less successful ones highlighted two common characteristics regarding relationship between networks, the issues they advocate around and their policy environments.

First, they are more likely to produce effects when their members construct a compelling framing of the issue, one that includes a shared understanding of the problem, a consensus on solutions, and convincing reasons to act. Second, their success is shaped by their ability to build a political coalition that includes individuals and organizations beyond their traditional base.

Interestingly, maintaining a focused frame and sustaining a broad coalition are often in direct tension, as incorporating diverse perspectives complicates the creation of a shared and narrow understanding of the problem – effective networks find ways to balance these two tasks . For instance, the success of advocacy for global tobacco control was underpinned by the network successfully advancing the wider uptake of its core frame (e.g. smoking as a public health issue, not an individual responsibility issue), expanding its frame to incorporate new network allies (e.g. making the economic case for tobacco control to government representatives) and drawing clear membership limits (e.g. excluding the tobacco industry).

Do advocates shape issues/environments or do issues/environments shape advocates? Towards an interactive theory

The third takeaway concerns the million dollar question – do successful advocates pick the ‘easy’ issues and operate in a policy environment conducive of change or are effective networks able to shape those issues and environments successfully? Our finding (as unsatisfying as it might seem) is that it’s both.

Take issue characteristics – some aspects of issues exhibit more inherent attributes (e.g. number of people affected by an issue; the scientific basis of a certain health condition). These attributes might change over time but are generally difficult for advocates to change. Other aspects of an issue are much more malleable as they are socially ascribed (e.g. who bears moral responsibility for addressing an issue, how an issue relates to certain cultural norms). These attributes are more conducive to being shaped by advocacy networks.

Similarly, policy environments create varying opportunities and threats to successful advocacy. At any point in time, they can include powerful opponents who sees their interests threatened by the network or can offer varying levels of interest by potential allies and funders. Since policy environments are by nature dynamic, they offer varying windows of opportunities at different times, which can be used and opened by networks.

To underscore these points – take the difference between the successful advocacy for global tobacco control vs. the failure of alcohol control as an example (here is a more in-depth analysis). Clearly, there are a few inherent issue characteristics (e.g. the more direct causal chain from usage to disease, the absence of a healthy consumption rate) that make it easier to frame tobacco usage as a public health issue and to vilify the industry than it is for alcohol. At the same time, these are not static characteristics as they have evolved over time. Consider the history of alcohol prohibition in the U.S. or the fact that the idea of a global treaty on tobacco control was considered highly unrealistic even a few years before its adoption. Furthermore, the alcohol industry has clearly learned from the tobacco industry’s experience in responding to criticism and successfully built a corporate social responsibility image (ironically, the UK’s newly appointed Development Secretary is a case in point as someone who moved from advising the tobacco to the alcohol industry).

In sum, I hope that considering these success factors for effective advocacy (around network, issue, environmental features) can help us to build better influence strategies. At the same time, we should be careful to not look at these factors too statically. After all, the strategic selection of advocacy issues should not only be based on their likelihood for achieving rapid success but also on their significance and the moral imperative of addressing them – even if the immediate possibilities of progress are slim. History teaches us that going after the seemingly impossible can appear like the most rational strategy in the long-run.

August 1, 2016

If politics is the problem, how can external actors be part of the solution? New World Bank paper

The new paper comes from Shanta Devarajan, the Bank’s Chief Economist for the Middle East and North Africa Region, (recently drafted in to help get the WDR to the finishing line) and Stuti Khemani, Senior Economist at its Development Research Group.

The new paper comes from Shanta Devarajan, the Bank’s Chief Economist for the Middle East and North Africa Region, (recently drafted in to help get the WDR to the finishing line) and Stuti Khemani, Senior Economist at its Development Research Group.

The World Bank seems currently to be awash with fascinating reflections and rethinking on politics and power. This one’s big message is perfectly captured in the title and abstract (my comments in italics):

‘Despite a large body of research and evidence on the policies and institutions needed to generate growth and reduce poverty, many governments fail to adopt these policies or establish the institutions. Research advances since the 1990s have explained this syndrome, which this paper generically calls “government failure,” in terms of the incentives facing politicians, and the underlying political institutions that lead to those incentives.

[starts off by acknowledging that it’s all about the politics, and requires a shift away from the purely technocratic ‘first best’ thinking the Bank has often shown in the past]

Meanwhile, development assistance, which is intended to generate growth and reduce poverty, has hardly changed since the 1950s, when it was thought that the problem was one of market failure. Most assistance is still delivered to governments, in the form of finance and knowledge that are bundled together as a “project.”

[this is pretty powerful stuff. For decades aid has been targeting the wrong thing, and is trapped in the straitjacket of ‘the project’. That combination has actually made matters worse in some cases, by shovelling money and kudos to failed institutions]

This paper proposes a new model of development assistance that can help societies transition to better institutions. Specifically, the paper suggests that knowledge be provided to citizens to build their capacity to select and sanction leaders who have the political will and legitimacy to deliver the public goods needed for development.

[the authors think donors should opt for a much more modest and general ‘enabling environment’ approach, getting information to citizens but acknowledging that what happens next is down to domestic politics, and largely out of their hands]

As for the financial transfer, which for various reasons has to be delivered to governments, the paper proposes that this be provided in a lump sum manner (that is, not linked to individual projects), conditional on the government following broadly favorable policies and making information available to citizens.

[Donors need to go back to general budget support to governments, with political conditionalities linked to the enabling environment point]

So much for the abstract. A few thoughts on the rest of the paper (only 22 pages, so even I’ve read it).

There is a clarion call for humility from donors faced with the reality of complex political and social systems:

‘There is an inherent hubris in assuming that external actors will have the capacity to identify the appropriate entry points and engineer reforms in the right direction, simultaneously solving both the technical policy problem and that of adapting it to political constraints. Ex ante, there is little reason to believe that the selected entry points are the right ones; they may make the situation worse. The incentives of donor organizations to show results and count reforms as success are further reasons to search for other approaches that do not depend entirely upon external agencies’ getting both the economics and the politics right.’

At a time when many researchers lament the deterioration in the quality of democracy and accountability in many countries, and considering Shanta works on the Middle East, the authors are strikingly upbeat.

‘During the past three and a half decades, the distribution of political institutions across countries has steadily shifted towards greater political engagement. (see graph) Political engagement within countries is also growing through elections at the local level.’

The thinking reflects Stuti Khemani’s recent book, Making Politics Work for Development, which argues that the

Only they know how to change the status quo, not donors

best lens for understanding government failure is not democracy v authoritarianism, but ‘political engagement’, defined as ‘the participation of citizens in selecting and sanctioning the leaders who wield power in government, including by entering themselves as contenders for leadership.’ That engagement happens under both democratic and non-democratic governments, albeit in different ways.

That’s all pretty high-level stuff – what are the implications for work on the ground?

‘For development assistance to be effective, the tradition of “bundling” knowledge and financial assistance—in a project, for instance—has to be abandoned. Knowledge assistance should be provided to citizens to help them in holding the government accountable. External actors should target transparency to nourish the growing forces of political engagement. External agents have technical capacity for generating new data and credible information through politically independent expert analysis. This technical advantage stands in sharp contrast to their lack of such advantage when it comes to building capacity and organizations for collective action from the outside.

What is different about the recommendation here is the importance of communicating to citizens, in ways that effectively shift citizens’ political beliefs and behavior on the basis of technical evidence. The traditional policy approach has treated leaders as the sole audience of expert analysis, and has treated communication to citizens as a matter not requiring scientific investigation. Communicating information to influence beliefs and political behavioral norms requires an understanding of the institutions within which and through which citizens form these beliefs.’

I found this all very thought-provoking in at least two big areas. First, should donors be doing more politics or less? The authors argue that outsiders are simply unable to get involved in the detail of domestic politics for reasons both  of knowledge and politics (interference). They should therefore concentrate on creating an enabling environment through knowledge and its dissemination.

of knowledge and politics (interference). They should therefore concentrate on creating an enabling environment through knowledge and its dissemination.

But the opposite conclusion, shown in Thinking and Working Politically, Doing Development Differently etc, is that donors can indeed get involved, but need to be far smarter and more immersed in local contexts to be able to do so.

Second, if you are sceptical about the Bank, this looks suspiciously like an abdication of responsibility. There’s (another) big row going on in Washington at the moment, with NGOs claiming that the Bank is watering down the social and environmental safeguards on its lending (Oxfam agrees). This paper could easily provide the intellectual justification for this – ‘hey we can’t do politics so let’s replace all those safeguards with some vague (and easily fakeable) conditions on transparency and information, then bung grants to governments, no questions asked.’

As usual, I’ve got feet planted firmly on both sides of the fence on both of these dilemmas. Painful, but I’m getting used to it.

July 31, 2016

Links I Liked

By the way, I’m heading for the US East Coast (DC, NYC, Boston) to launch How Change Happens from 28th Nov  to 10th Dec. If you are interested in organizing an event, please get in touch.

to 10th Dec. If you are interested in organizing an event, please get in touch.

The new Fortune Global 500 is out. 3 of the top 4 companies are Chinese.

‘All these theories – counterinsurgency warfare, state building – were actually complete abstract madness. They were like very weird religious systems, because they always break down into three principles, 10 functions, seven this or that.’ Britain’s new Minister of State for Development, Rory Stewart in a brilliant 2014 interview. Hope he stays that interesting now he’s in government.

Politics matters, so what? Time for bigger bets (and more learning) on adaptive programming. Excellent from Alan Hudson of Global Integrity.

Are log-frames holding us all back from effective learning and adapting? DFID’s Pete Vowles reflects on theory v practice

Cash transfers: what does the evidence say? New ODI review

Reality TV meets good governance. Integrity Idol, to find the most honest bureaucrat, is now showing in Nepal, Pakistan, Liberia and Mali

Economics: The Users Guide: Brilliant 11m RSAnimate of Ha-Joon Chang introducing his latest book.

July 28, 2016

Getting carbon inequality onto the political agenda: the lessons of Brexit

Guest post from Dario Kenner who describes himself as ‘an independent researcher currently exploring the links between policies to

reduce inequality and ecological footprints

’

Guest post from Dario Kenner who describes himself as ‘an independent researcher currently exploring the links between policies to

reduce inequality and ecological footprints

’

In a fascinating post-Brexit blog George Marshall makes comparisons between the Remain campaign and how to/how not to successfully communicate on climate change issues. He says while the Leave campaign had a compelling storyline based on Let’s Take Back Control the “Remain storyline was far less coherent. Like climate change, it lacked a clear external enemy.” So does this mean we need to identify a more tangible external enemy, such as the individuals with the biggest carbon footprints, to mobilise people on climate change?

Marshall goes on to argue “In the case of climate change the problem is caused by all of us, however hard we try to project blame onto oil companies or high carbon polluters.” I fully agree bringing down the UK’s emissions will require all of us to make changes and so maybe it’s not helpful to blame others as an excuse for us to continue our own far too carbon-intensive lifestyles. But I also think that alongside the society-wide changes that are required we cannot ignore carbon inequality. The danger of not talking about high emitters is that they get away with it. This matters because there are indications of extreme differences between households in the UK.

In Oxfam’s report Extreme Carbon Inequality it’s estimated that the richest 10% of the households emit around 24 tonnes of CO2 per capita compared to the poorest 50% of households who each emit around 5 tonnes of CO2 per capita. Meanwhile French economists Thomas Piketty and Lucas Chancel estimate the richest 1% in the UK have the largest emissions per person.

It’s important to campaign on carbon inequality because of the link with economic inequality. The most extreme examples of rising income and wealth inequality are the countries where there is ‘plutonomy’. Oxfam America researcher Nick Galasso explains this word (based on research by Citibank) describes an economy where a rich minority “control most of the wealth and income, and consume nearly all the goods and services.” Countries that some researchers argue are plutonomies include the UK, along with the United States and Canada. What’s interesting is that these three countries top the carbon inequality chart above. Exploring the relationship between plutonomy and carbon inequality seems like an obvious area that needs more research e.g. building on Oxfam’s research on inequality in the UK and on carbon inequality (see more ideas on this research agenda from an expert workshop at IIED in April).

It’s important to campaign on carbon inequality because of the link with economic inequality. The most extreme examples of rising income and wealth inequality are the countries where there is ‘plutonomy’. Oxfam America researcher Nick Galasso explains this word (based on research by Citibank) describes an economy where a rich minority “control most of the wealth and income, and consume nearly all the goods and services.” Countries that some researchers argue are plutonomies include the UK, along with the United States and Canada. What’s interesting is that these three countries top the carbon inequality chart above. Exploring the relationship between plutonomy and carbon inequality seems like an obvious area that needs more research e.g. building on Oxfam’s research on inequality in the UK and on carbon inequality (see more ideas on this research agenda from an expert workshop at IIED in April).

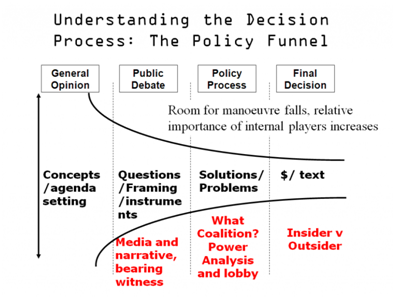

Duncan argues (and I agree) that the issue of carbon inequality currently lies right at the start of the policy funnel. So this means it’s still about agenda setting and doing more research on this nascent area. As part of this work, or at the next stage of the policy funnel, the debate could be framed around:

this means it’s still about agenda setting and doing more research on this nascent area. As part of this work, or at the next stage of the policy funnel, the debate could be framed around:

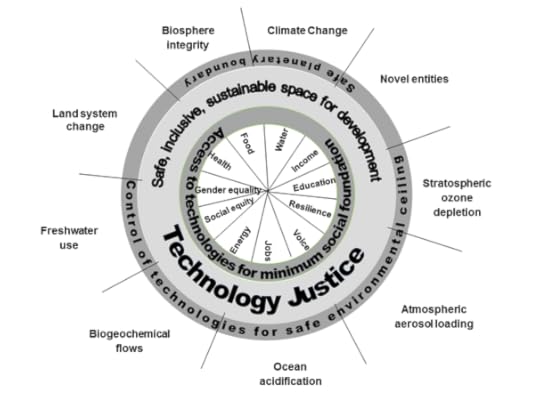

Why it’s a problem: Addressing carbon inequality is part of the work on reducing total emissions whilst at the same ensuring everyone has a minimum standard of living. See Kate Raworth’s work on ‘doughnut economics’ based on the idea that “between social and planetary boundaries lies an environmentally safe and socially just space in which humanity can thrive.”

Moral/social justice arguments: It’s not fair that a minority of rich people in the UK have such large carbon footprints (polluter pays). The richest also have the most resources to change their behaviour (capability to pay) e.g. by installing solar panels or buying an electric car (in a way this is like applying the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities within countries).

Pragmatic arguments: Reducing the consumption-based emissions of the richest people makes sense because it is a significant component of total emissions. In addition the example of the richest puts pressure on those below them to pursue carbon intensive lifestyles (conspicuous consumption). And is it easier to achieve (rich people’s consumption more elastic/easily influenced by price signals, taxation, regulation)?

Then in future (when hopefully carbon inequality is on the radar) the focus would be on building coalitions to pressure policy makers to act. As many people are saying, including Naomi Klein, dealing with climate change is not  just an environmental issue. It’s about social justice. So excluded groups (e.g. women, children, disabled people, and ethnic minorities who live in poverty) and groups campaigning on social inequalities could come together to demand that the richest reduce their large carbon footprints and so both free up carbon space for the less privileged and reduce overall emissions (this will be especially important in countries in the global south where it’s likely that a small elite have huge carbon footprints while marginalised people have zero or tiny footprints). These coalitions could campaign for the revenue from policies that target the richest, like luxury taxes on carbon intensive goods, to fund things like renewable energy.

just an environmental issue. It’s about social justice. So excluded groups (e.g. women, children, disabled people, and ethnic minorities who live in poverty) and groups campaigning on social inequalities could come together to demand that the richest reduce their large carbon footprints and so both free up carbon space for the less privileged and reduce overall emissions (this will be especially important in countries in the global south where it’s likely that a small elite have huge carbon footprints while marginalised people have zero or tiny footprints). These coalitions could campaign for the revenue from policies that target the richest, like luxury taxes on carbon intensive goods, to fund things like renewable energy.

Over the next few years of uncertainty the policy funnel is going to be very busy with sorting out the post-Brexit mess. Also it will probably be very difficult to convince politicians to talk about carbon inequality because they are often members of the richest households who have the largest carbon footprints. So I think it’s the long game here (unfortunately) meaning the first step is to get a debate going on carbon inequality in the UK (and elsewhere) and what to do about it.

July 27, 2016

Deworming Delusions and the flimsiness of ‘evidence-based policy’

This post is co-authored with Mohga Kamal-Yanni (right)

Should I blog about things that are way over my head? Well it’s never stopped me in the past…… My LSE colleague Tim Allen, along with Melissa Parker and Katja Polman have edited an issue of the Journal of Biosocial Science on ‘Biosocial Approaches to the Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases’. It’s open access and worth a skim, because even though it’s health-techie, it contains some pretty explosive stuff.

In particular Tim and Melissa lob another can of petrol on the ‘Worm Wars’ fire with ‘Deworming Delusions’ a damning account of the way routine deworming has become an iconic development intervention in East Africa on the basis of highly questionable evidence and dodgy ethics.

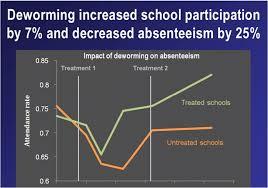

Nice graph, but is it true?

To recap, deworming school age children is claimed to improve attendance rates, and so educational attainment. A famous 2004 study by Michael Kremer and Edward Miguel using data from Kenya in the late 1990s found a reduction in absenteeism of 25%, following deworming with albendazole at 6-month intervals. On the basis of this study, a vast industry was founded – ‘According to the Gates Foundation, this is the largest public health programme ever attempted. The relevant tablets are being donated in huge quantities by leading pharmaceutical companies, and free preventive chemotherapy is being rolled out on a massive scale, with countries in Africa setting the pace.’

But that edifice is pretty shaky. First Allen and Parker review the many conflicting studies and conclude:

‘Assertions about the effects of school-based deworming are over-optimistic. The results of a much-cited study on deworming Kenyan school children, which has been used to promote the intervention, are flawed, and a systematic review of randomized controlled trials demonstrates that deworming is unlikely to improve overall public health.’

Tim’s an anthropologist and so spends a lot of time investigating how people on the ground understand what is going on. His approach is the exact opposite of trying to distil an impersonal, decontextualized ‘scientific truth’ about the efficacy or otherwise of drug programmes – he highlights the human dimension and concludes:

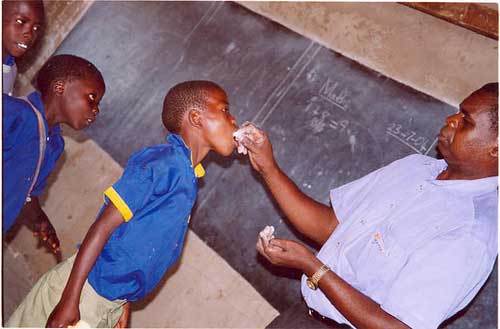

‘There are social problems arising from mass drug administration that have generally been ignored. Notably, there are serious ethical and practical issues arising from the widespread practice of giving tablets to children without actively consulting parents.’

It was this second aspect that got my attention (I really can’t follow the endless to and fro over methodology between

Anyone ask their parents?

protagonists in the Worm Wars). The authors point to a WHO recommendation in ‘School Deworming at a Glance’: ‘Don’t waste time and resources trying to examine each school or child. Deworming drugs are safe and can be given to uninfected children. No individual diagnosis, or assessment of each school is needed.’ The trouble is that:

‘Research carried out in Uganda and Tanzania has shown that deworming tablets can have side-effects, which are viewed as serious in local terms. Many children complained of stomach upsets after being treated in schools, some adults were incapacitated for days, and there were uncorroborated rumours that a few individuals had died. Such experiences and stories led to widespread anxiety and fear, and fostered rumours about the real purpose of the treatments. They also prompted a different kind of resistance in the form of a refusal to distribute or take the tablets, and occasionally confrontations with angry parents. …. If schools in a high-income setting were instructed to treat all children with a drug regime that would only benefit a minority, it would raise concerns. Indeed, it would probably be viewed as completely unacceptable to roll out such treatment without securing the consent of parents beforehand.’

But for the Worm War battlers, the authors conclude ‘the issue at hand is the divergent interpretations of data published in an old paper, rather than the actual effects of deworming policies on African children and their relatives’.

My impressions from all this? That the solidity of ‘evidence-based policy’ is often much more tenuous than is claimed – what is presented as ‘hard evidence’ is often contested just as fiercely as any historical or social science claim. The search for scientific certainty can easily lead researchers into ignoring the ‘biosocial’ – the interplay of norms, practices, opinion, politics and power that shapes how any apparently neutral intervention plays out. And maybe that we need more anthropologists as well as medics and economists.

Other essays in the issue address this wider point. In the introduction on the wider topic of “neglected tropical diseases”, the editors say:

Words on worms

‘Social priorities, social relations and social behaviour profoundly influence the design, implementation and evaluation of control programmes. Yet, these dimensions of neglect are, themselves, neglected. Instead, emphasis is being placed on preventive chemotherapy – a technical, context-free approach which relies almost entirely on the mass distribution of drugs, at regular intervals, to populations living in endemic areas.’

I asked one of Oxfam’s health gurus, Mohga Kamal-Yanni, for her views, and got this in response:

I share a lot of their concern on programmes that ignore the local (and medical actually) realities and needs. The world faced the same issue in responding to Ebola. Donors wanted to rush workers in space suits to tell communities what to do and tell patients to come to treatment centres (where people knew they would die). It took few valuable months for donors and governments to realise that they had to first understand the local reality and to engage people in planning and performing activities.

Worms eat away kids’ nutrients and therefore negatively affect their health and their cognitive abilities. Deworming programmes could be beneficial to kids’ health and education if they were implemented with local knowledge and participation. Like many development programmes, it is not a question of what, but how.

I loved that somebody critiques the perception of “community” as a homogenous group that loves and cares for each other. Such beliefs are also widely accepted even within NGOs, as if people in the South are different from people here. I remember in the 80s an Oxfam engineer was shot at because of disputes over the site of the water projects in a small isolated village. For me “community” equals power relations whether that grouping of people is a remote village in Sierra Leone or a neighbourhood in London.

However, I disagree with the authors on their analyses of the concept of “neglected diseases”. I think the concept has been very useful in raising attention and investment in research for treatment of diseases such as TB and sleeping sickness, where the only options available for doctors have been very old complicated regimes or even toxic medicines. In reality these diseases have been way off the radar screen of pharmaceutical companies because they will not make profits from selling a medicine to a poor African patient. It is only now, after much global effort, including by civil society, that governments, the pharmaceutical industry and philanthropist have engaged in researching new diagnostics and medicines for these diseases. It is worth noting that some of the medicines used for deworming, like albendazole, were actually developed for veterinary use (where profit is possible) and are very cheap to produce. “Neglected diseases” are the stark example of the failure of the current global R&D system to produce health technologies needed for public health. The system is driven by commercial profits based on pharmaceutical companies’ monopoly on medicines.

I wish I had time to blog about socio-medical interventions!’

Well now she has – note to colleagues, careful when sending me interesting emails, you never know where they’ll end up……

And here’s Tim presenting his paper (30m), and then being interviewed (20m)

July 26, 2016

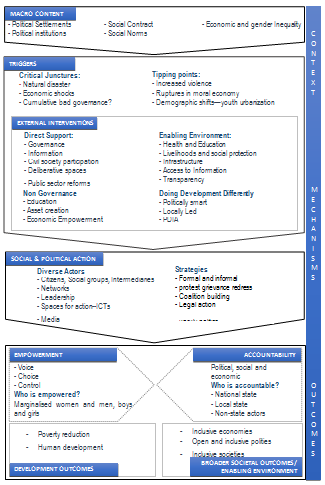

I need your help: Theories of Change for promoting Empowerment/Accountability in Fragile States

I love the summer lull. Everyone heads off for holidays, there are no meetings, so I can get my head down and

Somalia: Anyone seen a good Theory of Change?

write. Last year, it was wrestling How Change Happens to the finishing line. This year is less cosmic, but still interesting, and I need your help.

Subject: Theories of change for Empowerment and Accountability (E&A) programming in Fragile and Conflict Affected States (FCAS). This is one of the inception papers for a new, acronym-tastic research programme on E&A in FCAS, led by IDS, with Oxfam and several others. Findings a couple of years.

The task: An evidence synthesis paper (full ToRs here – ToRs Synthesis paper on Theories of Change Action in Fragile and Conflict States).

Given the particularities of context, E&A outcomes in FCAS are expected to be achieved through somewhat different pathways, in which informal institutions, a diversity of non-state actors and local states play a greater role than in other settings. Donor interventions have so far focused on working initially on the supply side (through public sector reform efforts) and now more on the demand side (the citizen-led accountability work). However, it is increasingly clear that neither of these strategies are delivering the scale of change that is needed—and there has been more of a shift towards ‘politically smart, locally-led’ approaches.

This synthesis paper will unpack the different theories of change currently used to guide support for social and political action for E&A in FCAS, and how the evidence stacks up against them.

What I’m looking for – sources:

Existing literature or systematic reviews

Relevant documentation from networks (Developmental Leadership Program, Doing Development Differently, Thinking and Working Politically) and the Overseas Development Institute

Relevant documentation from DFID (eg work in Mozambique), World Bank, SDC and DFAT

Relevant documentation from INGOs

And of course, because it’s about theories of change, there has to be a diagram (apologies for lousy quality – no link to fuzzy thinking, obvs)

Over to you – please send links, documents etc either via comments or direct via email.

July 25, 2016

The World Bank is having a big internal debate about Power and Governance. Here’s why it matters.

Writing flagship publications in large institutions is a tough job. Everyone wants a piece, as different currents of

Flagships sometimes run into trouble

opinion, ideology or interest slug it out over red lines and key messages. Trying (and failing) to write one for Oxfam once put me in hospital.

So no surprise that the flagship of flagships, the World Bank’s annual World Development Report, on Governance and Law, is currently experiencing some mid-flight turbulence. In an attempt to figure out what all the fuss could be about, I’ve luckily been able to read bits and pieces of an early draft.

I know NGO types aren’t supposed to say this, but it’s really impressive (don’t worry, I’ll get on to the weaknesses later). Coming from the Bank, it’s a major step forward, capturing, consolidating and mainstreaming elements of systems thinking, Thinking and Working Politically, Doing Development Differently etc. Examples: context specificity, path dependence, evolution, critical junctures, feedback mechanisms, the need for constant adaptation, how multiple actors interact to produce both intended and unintended consequences. The conclusion is that reformers should focus on strengthening the enabling environment, rather than pushing specific reforms.

A huge contribution is that it squarely locates power as a core issue both to understanding and influencing development. It identifies the ‘policy arena’ as the missing link between formal rules and development outcomes. The policy arena is where all the interesting stuff happens: where different groups bargain over cash, policies and

Maybe a bit more political analysis?

implementation. The arenas are both formal (parliaments, government departments) and informal (backroom deals, Old Boy Networks). The distribution of power (asymmetric or inclusive?) determine how policy arenas function and whether they produce good development outcomes, so reshaping those arenas in a more inclusive, effective direction becomes a core task for anyone working on governance and law.

This is good stuff (despite some caveats, below) and with luck, ‘Policy Arena’ could become the new euphemism du jour for power and politics, taking over from political economy, governance etc.

Other stuff I liked:

Really good, nuanced approach to China, a great improvement on the standard US political science view that China is really just an anomalous governance disaster waiting to happen (eg Acemoglu and Robinson).

Guarded optimism that when it comes to governance, turkeys regularly vote for Christmas (elites pushing through reforms that limit their power in order to stay in power, as political insurance for when they lose power, or to improve stability), and an excellent set of insights on why they do so

Good to see citizen engagement (including mobilization) as one of the key drivers of change, along with elite bargains and international influence.

I like its very political understanding of aid (others in Oxfam may disagree!) It argues that aid is neither inherently good, nor inherently bad for development. What matters is how aid interacts with prevailing power relations and impacts governance.

But of course, I wouldn’t be working for an NGO if I didn’t want it to go further:

In its preference for abstraction, it downplays how differently governance and law are experienced by different  disenfranchised/excluded groups. Gender gets an occasional look in, but youth, ethnicity, disability, sexuality etc are all conspicuously absent from what I read despite their importance in the evolution of norms and legal systems. Trade Unions also appear, though as often as a problem, as an expression of empowerment.

disenfranchised/excluded groups. Gender gets an occasional look in, but youth, ethnicity, disability, sexuality etc are all conspicuously absent from what I read despite their importance in the evolution of norms and legal systems. Trade Unions also appear, though as often as a problem, as an expression of empowerment.

Its understanding of power is limited/compartmentalized, with a focus on formal power (both de jure and de facto). There is no discussion of hidden/invisible power, or power within. It is pretty remiss not to mention Foucault, Lukes (or indeed Oxfam’s very own Jo Rowlands!) in a discussion of power.

Although it’s good to see a focus on citizen engagement, it seems very superficial – eg no discussion of granularity within social movements and I would hope to see more on civil society space.

Does this matter? Advocates tend to get agitated about whether the WDR reflects the Bank’s behaviour on the ground – not unreasonable given the gulf that often separates research and practice. But in my view that is not the right emphasis. The WDR is not intended as a manifesto, or description of Bank activities, but as a contribution to debate, both within the Bank and beyond. The research effort is awesome (apart from anything else, it is a great literature review, with fascinating case studies).

Will it have much indirect influence, either within the Bank or more broadly? I’m a bit worried to be honest. Firstly, it depends on how much it is watered down in the current discussions within the Bank. But secondly, it is pretty inaccessibly written and this draft lacks the punchy diagram or memorable overall trope that could cut through to a wider public. Some WDRs have a big impact on policy thinking, and others sink without trace – I really hope this one doesn’t end up in the latter camp, because there is some truly valuable stuff in here.

Will it have much indirect influence, either within the Bank or more broadly? I’m a bit worried to be honest. Firstly, it depends on how much it is watered down in the current discussions within the Bank. But secondly, it is pretty inaccessibly written and this draft lacks the punchy diagram or memorable overall trope that could cut through to a wider public. Some WDRs have a big impact on policy thinking, and others sink without trace – I really hope this one doesn’t end up in the latter camp, because there is some truly valuable stuff in here.

Best outcome? The Bank’s bigwigs, from Jim Kim downwards, get behind this and the WDR emerges as good as/better than the current draft. Then the Bank gets together with other aid organizations and sets up an implementation unit/do tank to turn its analysis into concrete plans for doing development differently, and puts some resources behind trying them out, including making sure the Bank has enough staff to support such ideas (its capacity in this area seems to be on the downturn of late). Well you can always dream…..

July 24, 2016

Links I Liked

How was your week? Write any top emails?

Internal Oxfam stuff, but important. Winnie Byanyima explains reasoning behind relocating Oxfam International’s office to Nairobi

Ten facts about conflict and its impact on women [h/t Emily Brown]

DFID has a new, high profile and v thoughtful Minister of State in Rory Stewart. Here he is on why democracy matters

‘End this report writing madness now’. Enjoyable Deborah Doane rant about the avalanche of the unread, with a passing swipe at Oxfam

Could economists have done any better over Brexit? Tim Harford on limits of evidence/experts in public debate

Nice balanced analysis of the role of social media (especially whatsapp) in the recent protests in Zimbabwe, compared to traditional face to face organizing

Where do African women have more power? In countries emerging from war.

Obama’s legacy for international development: lots of new initiatives but also preventing an even bigger global crash in 2008

Why “what works?” is the wrong question: Evaluate ideas not programs.

‘We’re the Superhumans’ Backgrounder on utterly brilliant trailer for Rio Paralympics 2016.

July 21, 2016

How can rethinking innovation achieve Technology Justice?

Amber Meikle of Practical Action, introduces ‘

Rethink, Retool, Reboot Technology as if people and planet mattered’, a new book on a massively neglected topic

Amber Meikle of Practical Action, introduces ‘

Rethink, Retool, Reboot Technology as if people and planet mattered’, a new book on a massively neglected topic

The history of mankind’s development has long featured technology – from early cultivation techniques, fire, and the wheel, all the way to 3D printing and nanotechnology. Today, technology underpins all aspects of everyday life: from how our food is produced and how we access water and energy at home and work, to transport, our health and even education.

How we access, develop and use technology will also determine our path to meeting the two big challenges facing us today: ending poverty; and finding a path to an environmentally sustainable future for everybody on the planet.

That’s why the recent renewed appreciation and interest in the central role of technology in sustainable development is good news for us all. Though still finding its feet and mandate, the very existence of the new Technology Facilitation Mechanism is acknowledgement that technology will be critical to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals. And it’s about time too, because development faces twin technology crises.

Firstly, billions of people remain without access to essential technologies: 3.2 billion people in Africa and Asia lack internet access; 30 per cent of the world’s population can’t access the WHO’s list of essential medicines; the majority of developing country farmers can’t get technical advice.

Firstly, billions of people remain without access to essential technologies: 3.2 billion people in Africa and Asia lack internet access; 30 per cent of the world’s population can’t access the WHO’s list of essential medicines; the majority of developing country farmers can’t get technical advice.

At the same time largely unfettered use of technology has led to vast and unintended negative consequences for the environment: take climate change, resulting in part from our addiction to fossil fuel technologies; the impending health crisis likely to result from our overuse and misuse of antibiotics; and the recent news that our intensive approaches to agriculture has led to ‘unsafe’ loss of biodiversity in more than half the world’s land.

These examples of injustice in technology access and use are compounded by a third injustice, in innovation. More often than not, patterns and processes of innovation mirror and exacerbate existing injustices in people’s access to and use of technology. That is because technological innovation is not driven by a focus on the most pressing social and environmental challenges we face, or improving the conditions of those living in poverty. Instead, innovation efforts, on the whole, serve those most able to pay rather than those most in need. The result is still greater technological inequality.

Innovation in health is a clear example: it has long been known that just 10 per cent of global health research expenditure is spent on the health problems of developing countries (think malaria, HIV, diarrheal diseases), despite the fact that more than 90 per cent of the world’s preventable deaths occur in those countries. This 10/90 gap has persisted since 1990, despite an eight-fold increase in research funding. It’s well known that the primary reason is that there is no market incentive to develop drugs to treat the poor. It’s the same story in agriculture, with a lack of market incentives resulting in minimal research into technologies that could transform the livelihoods of smallholder farmers in the developing world.

In his new (open access) book Rethink, Retool, Reboot: Technology as if people and planet mattered, Practical Action’s former CEO Simon Trace calls for urgent moves to:

rethink the purpose of our technological endeavour and how we provide access to and govern the use technology today.

retool – to change the alignment of our innovation systems to deliver technology that is socially useful and addresses the key challenges of poverty and environmental sustainability.

Above all, our relationship with technology needs a reboot. We need a different frame of reference – Technology Justice – to provide a radically different approach to our oversight and governance of the development and use of technology.

By drawing on Rockstrom’s theory of planetary boundaries and Kate Raworth’s doughnut of social and planetary boundaries, we have recast the doughnut (see diagram) to demonstrate what this reboot of our relationship with technology would mean. And how the principle of Technology Justice could help us to meet the social foundation, and stay within planetary boundaries.

The inner circle represents a minimum set of technologies that have to be accessed universally in order to meet the social foundation. And the outer circle represents the level of controls that we have to exert on our use of technology to remain within those safe boundaries. The core of the doughnut then represents not only the safe space for development, but the space of Technology Justice.

So, if Technology Justice is a world where:

Everyone has access to the technologies they need to achieve a reasonable standard of living in a way that doesn’t prevent others now and in the future from doing the same, and

The focus of efforts to innovate and develop new technologies is firmly centred on solving the great challenges the worlds faces today – ending poverty and providing a sustainable future for everyone on our planet

Then this lens helps us to see that some choices lead us in the direction of safe space, while others take us beyond, or contribute little to meeting the social foundation. But, while this is pleasing conceptually, of course, immense practical and political challenges remain to doing this. It will require systemic change on a massive global scale. It will have repercussions on how we approach and incentivise science, technology and innovation in all sectors, as well as who does it.

contribute little to meeting the social foundation. But, while this is pleasing conceptually, of course, immense practical and political challenges remain to doing this. It will require systemic change on a massive global scale. It will have repercussions on how we approach and incentivise science, technology and innovation in all sectors, as well as who does it.

Among other things, it requires agreement on a minimum set of essential technologies that are needed to deliver on the SDGs and help people meet the social foundation. The research void on how national innovation systems work in the developing world must be filled. Subsidies supporting use of harmful technologies must be reassigned to sustainable alternatives. Public debate must be part of the approach of managing social and environmental risk from new technologies. Alternative models are needed to finance and incentivise innovation that is based on need.

The challenges are vast, but it’s time to step up and finally make technology work for people and for planet. Please join the conversation on Technology Justice.

Rethink, Retool, Reboot Technology as if people and planet mattered, is available from Practical Action Publishing or as an Open Access PDF

July 20, 2016

Parts of the aid system just don’t work – the dismal cycle of humanitarian response

Every now and then an email stops me in my tracks, reminding me that Oxfam is stuffed full of bright, motivated,  altruistic people. Here’s one I got a few weeks ago from Debbie Hillier, one of our Humanitarian Policy Advisers, in response to my request for thoughts on the state of the aid business. Her views are fleshed out in ‘A Preventable Crisis’, a new report published this week:

altruistic people. Here’s one I got a few weeks ago from Debbie Hillier, one of our Humanitarian Policy Advisers, in response to my request for thoughts on the state of the aid business. Her views are fleshed out in ‘A Preventable Crisis’, a new report published this week:

‘Hi Duncan

Here is a current example of how the aid system doesn’t work.

El Niño events and other droughts are forecast months in advance. There is of course some uncertainty in the forecasts, but nonetheless, there is often a high probability of a natural hazard. And with major droughts/El Niño/La Niña, these can affect many millions of people.

So there are situations of high probability and high impact – like the current El Niño. And these are situations where we know what the solutions are. There are far fewer complicating political factors than in conflict – we know what to do.

If this was the private sector, there would be a significant response at this point. However the aid system does not work like this.

Humanitarian funding is only available at scale when there is a serious crisis – eg major flooding or famine. Humanitarian funding is not available at scale to respond early.

Humanitarian funding is only available at scale when there is a serious crisis – eg major flooding or famine. Humanitarian funding is not available at scale to respond early.

Public appeals only work when there is huge media coverage, and for food crises this relies on visual suffering – starving children, by which time we have collectively failed.

Institutional funding can be made available, but the amount depends on geopolitical factors, and some self-interest – which is often not present, and certainly isn’t there for this El Niño. And currently is competing with the crises in Syria and elsewhere.

This is despite the humanitarian mandate to prevent suffering. And despite the fact that there is unequivocal evidence that early response is much cheaper than late response, as well as reducing suffering and maintaining development gains. Early response means rehabilitation of wells, rather than water trucking. It means community care on nutrition, rather than therapeutic feeding centres. It means commercial destocking rather than restocking after the drought. The evidence is totally clear that early response is cheaper and helps to build resilience.

Humanitarian funding is generally for short term use – eg 6-12 months – and sometimes must be explicitly ‘lifesaving’ – which precludes early action.

Quite a lot of donors now have ‘Rapid Response Funds’ which enable a quick disbursal of funding for a quick onset crisis – eg Nepal earthquake. But no donors – to my knowledge – have an ‘Early Response Fund’ to enable early response to drought to prevent deterioration.

Development funding streams are unable to respond at scale to drought. Development programmes (of governments, as well as donor-funded) take a long time to negotiate (eg up to a year to agree a proposal, which clearly doesn’t work for crises) and are normally relatively inflexible over their lifespan (3-5 years).They are unable  to respond to the changing context. There are some programmes that are designed right from the start to be flexible (e.g. Kenya’s Hunger Safety Net Programme, which was designed specifically to respond to recurrent drought), to scale up and down, but this appears to be fairly exceptional. And there are a few programmes which include ‘crisis modifiers’, where humanitarian funding is ‘tucked in’ to a long term development programme and can be accessed quickly – but again these are few.

to respond to the changing context. There are some programmes that are designed right from the start to be flexible (e.g. Kenya’s Hunger Safety Net Programme, which was designed specifically to respond to recurrent drought), to scale up and down, but this appears to be fairly exceptional. And there are a few programmes which include ‘crisis modifiers’, where humanitarian funding is ‘tucked in’ to a long term development programme and can be accessed quickly – but again these are few.

So Early Response falls between humanitarian and development funding envelopes. Oxfam went to a humanitarian donor last October for drought response funding for Guatemala and Honduras and was told it was ‘too resiliency’. It was refused. We took the ‘resiliency’ bits out and it was funded. Ridiculous.

The lack of major funding available for early response to drought, and indeed to Disaster Risk Reduction which is also about preventing/mitigating the impacts of a natural hazard, means that people are much more vulnerable than they need to be and people suffer unnecessarily. Only 0.7% of total ODA is spent on DRR, whereas Oxfam considers a figure of 5% to be more appropriate,.

More broadly, while it is brilliant that overall humanitarian funding has increased yet again in 2016, the appeal process is hardly fit for purpose. We would not be happy if a fire brigade has to pass the hat around before being able to respond to a fire, yet that’s precisely how the humanitarian funding system works. In time-critical crises – eg Ebola – this was highly problematic. And in situations where nobody cares – like El Niño now – we are stuck.’

Nothing to add.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers