Duncan Green's Blog, page 140

June 20, 2016

Why do people flee their homes? The answers may surprise you

Yesterday was World Refugee Day and a new UN report put the total number of ‘forcibly displaced’ at 65.3 million. Most of those remained within national boundaries (internally displaced). Oxfam researcher John Magrath summarizes a recent study on the  causes of internal displacement

causes of internal displacement

Why do people become displaced? That is, forcibly displaced in that they have, or believe they have, no other choice but to leave their homes? You would think we would know. After all, the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) in its latest annual report points out that in 2015 a record number of 27.8 million people were newly displaced; and the reasons were conflict, violence and disasters. We are familiar with the overall picture: the Middle East and North Africa account for over half those displaced by conflict and violence; South and East Asian countries, especially India and China, saw the most people displaced by disasters. Once people are displaced, they tend to stay displaced so the numbers add up cumulatively; in 2015 there were nearly 49 million in total living as internally displaced people just because of conflict and violence.

Why do people become displaced? That is, forcibly displaced in that they have, or believe they have, no other choice but to leave their homes? You would think we would know. After all, the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) in its latest annual report points out that in 2015 a record number of 27.8 million people were newly displaced; and the reasons were conflict, violence and disasters. We are familiar with the overall picture: the Middle East and North Africa account for over half those displaced by conflict and violence; South and East Asian countries, especially India and China, saw the most people displaced by disasters. Once people are displaced, they tend to stay displaced so the numbers add up cumulatively; in 2015 there were nearly 49 million in total living as internally displaced people just because of conflict and violence.

But dig beneath and beyond those figures, as IDMC does, and an even more disturbing picture emerges of reasons and trends. IDMC puts the spotlight on three issues that demand more attention. One is drought, of the kind exacerbated by this year’s El Niño event. That may seem unsurprising; after all, it is obvious that drought dries up precious water sources and scorches crops and as this moving video from Oxfam in the Dominican Republic shows, the result is that farmers get into debt and can end up selling their farms – their homes – and becoming wandering labourers.

However, IDMC finds that – perhaps surprisingly – there is relatively little information available about when and how drought leads to displacement, and therefore, about the true numbers of those internally displaced by drought. Perhaps because drought tends to be a creeping disaster, it may be more likely to add further pressure on households to send one or more of their members off to seek work elsewhere; that may be a relatively long-term and considered decision. Such people may be classed as voluntary or economic migrants, rather than as internally displaced. But not understanding the links to drought, or recognising people as being internally displaced as a result, may mask the (growing?) extent of the issue and may deprive people of access to attention and assistance.

The second factor behind displacement is even less recognised. That is, the numbers of people displaced

Mexico – migrants, IDPs or both?

by criminal violence associated with drug trafficking and gang activity. A new special report by FEWSNET on coffee in Central America highlights the pressures put on people by the gangs – the ‘maras’ – “forcing many people to avoid going to their farms during harvest, for fear of extortion, or their income is reduced because they have to pay a tax to save their lives”.

There is a direct and established link between criminal violence and migration – that is, the decision by people to get out of their country altogether and move to another one, as from Central America to the USA. But there is very little data on the numbers of people who move within a country, leaving their locality for another. Naturally, people fleeing criminal violence often do so in small numbers and keep a deliberately low profile. Such people, say IDMC, may ‘fall through the gaps’ when it comes to protection, “leaving them with little choice other than to embark on dangerous migrations”. If they are classified at all, they too may be seen as economic migrants; but they left “because they were or felt obliged to flee, rather than exercising a free choice to move solely to improve their economic circumstances”.

Darfur

The third reason behind mass displacement is – sadly – development; that is, development projects initiated by governments in the interests of ‘national development’. Such projects include big dams, infrastructure for major sporting events, ports, mines, parks and wildlife sanctuaries, special economic zones and urban renewal. Such projects displace, at a very conservative estimate, 15 million people per year. The lack of data here is truly disturbing, particularly because it can be deliberate; as IDMC says, even “those [figures] that are reported may be underestimates to increase the chances of the project being approved and funded”. And IDMC drily notes that when it comes to displacement by big projects, international humanitarian organisations “are not on the front lines….this may be due to lack of awareness, limited resources, restricted access and a wish to avoid jeopardising their relations with the authorities”.

The people who have to move in the national interest “usually pay the price for development projects and

Central African Republic

end up worse off”, and “impoverishing and disempowering people in the name of development also allows human rights abuses to continue unchallenged”. IDMC also notes that such projects create “an inflated sense of progress because indicators that track development….capture gains but not setbacks”.

Where does this leave us? Clearly much needs to be done to capture better data and enable better analysis and policy formation, and IDMC is busy pushing on these. But behind the figures are millions of individual human beings – people facing everyday threats, violence and insecurity who cannot see any escape and become mentally and physically ill; people up against a powerful faceless government who have no choice but to move or be bulldozed out of the way; people facing incessant drought who can’t see the rain coming again in the future. The common link is the loss of hope – and as Greek myth has it, hope is the last thing left to humans. If millions of people lose hope and sink into despair, the ramifications are tragic, disturbing – and potentially very dangerous.

June 19, 2016

Links I Liked

Never has ‘links I liked’ been more of a misnomer, but I have to start with the murder of my former

colleague Jo Cox. This was one of the more searching reflections on her death.

Which leads us on to this week’s EU Referendum, I guess. If you’re one of those diminishing band of voters that is still interested in facty stuff, the Institute for New Economic Thinking takes down Boris Johnson’s claim that the EU is ‘a graveyard of low growth’ and Owen Barder has handily annotated a largely fictitious pro-Brexit leaflet.

Meanwhile, a Mail-inspired petition forces a Commons debate on aid, and most MPs supported aid. Oops

Let’s try and lighten the mood:

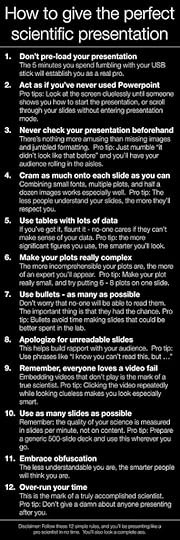

Some excellent advice from Andrew Hayward on how to give a top presentation.

And some smart videos:

Two nice parodies of TED talks (I’m enjoying the backlash). Thought Leaders and John Oliver, who to be fair is parodying anti-science, more than TED

This has to be the most relaxed bit of news reporting from the middle of a riot you will ever see.

And an 8th grader goes viral by giving his graduation speech in the style of the US presidential contenders (all of them, plus the President). It’s 8 minutes long, but worth hanging in there for his Bernie Sanders impersonation. [h/t Nick Corasaniti] His Trump is good, but who can match the original on the great City of Belgium?

June 16, 2016

RIP Jo Cox

I worked with Jo (Jo Leadbeater as she then was) for several years at Oxfam, where she ended up being head of the advocacy team in Oxfam GB. My main memory is of her relentless optimism and tigerish energy – she bounced around the office. She was an activist’s activist (she didn’t have much time for what she called my ‘beardstroking’).

In the words of Brendan, her husband (and another Exfamer):

‘Jo believed in a better world and she fought for it everyday of her life with an energy, and a zest for life that would exhaust most people.

She would have wanted two things above all else to happen now, one that our precious children are bathed in love and two, that we all unite to fight against the hatred that killed her.’

What a waste. A horrible day.

Today’s Guardian editorial here.

Here’s Jo in parliament, where the convention is to talk about your constituency in your maiden speech.

June 15, 2016

After the Summit: What next for humanitarianism?

Here’s this week’s vlog – still trying to sort out a better camera and sound, sorry!

Spent a fascinating morning recently, discussing the state of humanitarian response with a bunch of fairly senior people from inside ‘the system’ – UN, donors, INGOs etc. It was Chatham House Rule, so that’s as much as I can tell you about the event, but the good news is I can therefore draw out the interesting stuff and take all the credit…..

Humanitarians often seem particularly questioning and anxious – hardly surprising as they work in some of the most messy, chaotic situations, surrounded by the depths of human suffering, always short of money, always banging up against bureaucracy and head office. They can never do enough. Gallows humour comes as standard.

messy, chaotic situations, surrounded by the depths of human suffering, always short of money, always banging up against bureaucracy and head office. They can never do enough. Gallows humour comes as standard.

This group was no exception. They kept coming back to ‘the gap’ – between the 24/7 commitment of people working on the ground and the dead hand of the institutions; between the buzz and excitement in the side events at last month’s World Humanitarian Summit and the stultifying set speeches in the official plenary. Given the gap, how is the good stuff agreed at the WHS ever going to become reality? For example, what needs to happen to bridge the divide between humanitarian response and long term development? Or increase the proportion of humanitarian spending channelled via local organizations from 2% to 25% as agreed in Istanbul?

I went into How Change Happens mode. It is not enough to exhort the current system, in the title of a recent ODI report, that it is ‘time to let go’. Humanitarian organizations, like any other, have their circuits of power and incentives. As several participants pointed out ‘power is not ceded, it is seized’.

So let’s look at three sources of resistance to reform – ideas, interests and institutions – and the potential disruptors that could trigger a change in the system.

Ideas: The humanitarian principles of neutrality, independence and impartiality are deeply ingrained in the system. In practice, these are often dumbed down (at least rhetorically) to ‘we don’t think about power and politics, we just save lives’, making it very difficult to join up humanitarian response with longer term approaches (long term development, influencing) that see understanding and engaging with power and politics as central tasks. Lots of humanitarians are of course very conscious of the political roots both of human suffering and its redress.

Good or bad disruptor?

Disruptors: New frames such as resilience or systems thinking, which allow us to think of both humanitarian response and long term development in new, connected ways, could help overcome the intellectual divide. Historically, major failures (Rwandan genocide, Asian Tsunami) have played an important role in highlighting problems and shifting ideas and behaviours. Could Syria and its refugees have the same impact? Unfortunately, as yesterday’s post on Europe’s disastrous response to the Syrian refugee crisis argued, failure can lead to destructive change as well as the good variety.

Institutions: The ODI report sets out a series of institutional obstacles to improving humanitarian response. The aforementioned siloes between short-term and long term development (6 month or 1 year funding cycles really don’t work when emergencies are getting ever-longer: in some cases people have been in refugee camps for decades). The burden of rules and reporting procedures (known in Oxfam as ‘treacle’) that effectively exclude new or smaller actors from entering the system. The turf wars within the UN system and beyond. The layers of intermediaries (‘there are 6 or 7 procurement layers before money ever reaches the ground’).

Disruptors: New entrants (eg private foundations, or new emerging country donors, national organizations raising local resources) could bypass the institutional blockages and at the same time exert pressure for the traditional system to reform. New tech could help. And the reality of increasing numbers of SMEs (small and medium emergencies) will highlight the failings of the current institutional set up.

Interests: Turnover is a success metric for institutional leaders. In some cases, through the growing privatization of aid, it is also a source of profit. What would make them agree to ‘let go’ of their dominant position and hand over the reins of cash and power?

Disruptors: Besides the rise of new sources of money (new donors, domestic resources in developing countries), the big funders have the power to change incentives and behaviours by turning off or redirecting the flow of money.

Beyond exhorting people to ‘let go’, what can reformers in the humanitarian sector do to encourage disruption and move to the better systems set out in innumerable agency reports?

move to the better systems set out in innumerable agency reports?

One is to encourage an ‘enabling environment’ for disruption, for example by building the capacity and fundraising of local organizations, or spinning off more independent organizations to build diversity in the system. Or at the very least not closing down diversity by encouraging the kind of corporate monocultures that only fund ‘people like us’.

The second is to take a lesson from Milton Friedman’s book. Yes you read that right. In Capitalism and Freedom, the father of monetarism wrote ‘Only a crisis – actual or perceived – produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around. That, I believe, is our basic function: to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes politically inevitable.’

The key here is ‘actual or perceived’. Activists and researchers seeking change need not only to respond to undeniable crises, but do so early, and in part help them be recognized as such. In addition to high profile failures, existential threats to the system mentioned at the seminar include climate change, the rise of Daesh, the Sunni-Shia divide, the shift to cash transfers and refugees/migration. It is through these filters that policy makers and power holders can be persuaded to change.

Thoughts?

And here’s ODI’s Christina Bennett presenting Time to Let Go in a 4m video

June 14, 2016

European Governments’ treatment of refugees is doing long term damage to international law

Maya Mailer (@mayamailer), Oxfam’s

Head of Humanitarian Policy & Campaigns, reflects on a recent visit to Greece on the day it launches Stand As One, a big new campaign on refugee rights

Maya Mailer (@mayamailer), Oxfam’s

Head of Humanitarian Policy & Campaigns, reflects on a recent visit to Greece on the day it launches Stand As One, a big new campaign on refugee rights

I visited some of Europe’s refugee camps recently. Oxfam was founded in 1942 to help civilians that were starving in Nazi-occupied Greece, and now, more than 70 years later, we are once again active on Greece. Oxfam is working in camps in Lesvos and the mainland, providing clean water and sanitation, food, and helping people who have fled conflict and hardship to understand their rights.

In mainland Greece, there are around 45,000 people scattered across 40 different refugee camps that are run mainly by the country’s military. In the two sites I visited, refugees were living in rows of flimsy tents on hard rocky ground. Conditions were basic, in some instances squalid, and the air was thick with flies. I saw people in obvious need of urgent medical assistance. Greece is experiencing a deep, traumatic economic recession that complicates its efforts to respond to refugee needs – still, I never expected to see such a scene in wealthy Europe.

I spoke to a man from Syria, whose wife and four children were in Germany. Earlier this year, his family had travelled from Turkey to Germany via a combination of train, bus and car – it had taken them around seven days. A

Approximately 1,000 people are staying at Katsikas camp in the Epirus Region of Northwest Greece. Conditions are poor, with refugees living in army tents and exposed to the weather.

few weeks later, he set out to follow them but by then the so-called ‘Western Balkans route’ had been shut. He has been in the camp in Greece for months now and with the borders closed and uncertainty around how to claim for asylum, he doesn’t know when and how he will see his young children and wife again. The unilateral closure of borders in Europe has restricted the movement of people and it has left a thousand cruelties in its wake. Who gains when children are kept apart from their parents?

I walked on through the camp. A little girl ran to me, wanting to be hugged. She wouldn’t let me put her down. A volunteer was taking care of her and her baby sister, while her mother tried to find a doctor. I learnt later that their mother is haunted by what happened to her in Syria: her home was pulverised by a bomb, killing her close relatives. She doesn’t sleep at night.

In Syria, school, hospitals and residential areas continue to be hit. Civilians are caught between the bombs from the sky and shells and motors from the ground. Yet, European governments concluded a deal with Turkey in March that is predicated on pushing people fleeing that conflict, and others like it, away from Europe and back to Turkey – a country which is now home to at least two million refugees, more than any other country in the world.

There is a fundamental contradiction here. European governments call on Syria’s neighbours to keep their borders open, while they adopt policies of pushback. But Syria’s neighbours are buckling under the strain – and the failure of

Dadaab camp

European countries, as well as other rich countries, to adequately share responsibility for Syria’s refugees removes any incentive Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey might have to open their borders to those Syrians who can escape the conflict.

By outsourcing its border controls to Turkey, European governments triggered a domino effect. Soon after the EU Turkey deal, Turkey introduced visa controls for Syrians seeking to enter via third countries by sea or air. Inside Syria, according to the UN, some 500,000 people live in besieged areas, where they are literally imprisoned in their neighbourhood; some are starving to death. But even those Syrians who can move are finding it increasingly hard to enter neighbouring countries, and internal camps are building up in insecure areas along the borders.

A core tenet of international law – the right to seek protection in another country – is under threat. And it threatens all asylum seekers. Syrians, at least, still benefit from some public sympathy and, when they are able to access a fair asylum processes, the recognition rate is around 90 per cent in most countries (see UNHCR statistical yearbook). Other nationalities, such as Afghans, are being pushed even further to the margins – they’ve been dubbed the ‘The Refugees’ Refugees’.

By trading refugees for political concessions, the EU Turkey deal is demolishing the spirit of the international law and setting a dangerous precedent. In May, Kenya announced the closure of the Dadaab camp for refugees (above, right), saying that if Europe could turn away Syrians, then Kenya could do the same for the Somalis. It is possible that Kenya would have pursued this policy either way, but Europe’s current approach to migration is creating an environment where the chipping away of refugee rights can be more easily justified.

In a special report on migration, The Economist writes that ‘legal responsibilities to refugees cannot be separated from politics’. Yes, of course, international law does not float in a vacuum. And in many countries, rich or poor, European, Middle Eastern or African, the politics of migration is complex and often divisive. But European governments seem to be charting a course where ‘stopping’ migration – an unattainable goal – is becoming the sole driver of foreign policy. As part of this, Europe is considering plans to work with repressive governments such as Sudan and Eritrea to prevent the movement of people to Europe. Europe risks compromising its values, and cutting deals with such governments must surely store up problems for the future.

Volunteer Thor Foss from Vesteroy, Norway, comforts a woman who arrived from Turkey. Credit: Paula Bronstein

But it’s not all bleak. Around the world, there are countless acts of solidarity. In Greece, I saw teams of international and national volunteers working in the camps. Oxfam staffers told me about elderly Greek villagers inviting pregnant women into their homes when the women neared term to make sure they were in easy reach of hospital.

And The Economist, while calling for a response rooted in Europe’s political realities, concedes that ‘the policies of the next age of refugee management still depend on a spirit of compassion and humanitarianism’. In less than 100 days, two major summits on migration, one hosted by the UN and a separate summit hosted by President Obama, will take place in New York on 19 and 20 September. They are a chance for world leaders to show that spirit, put a halt to the race to the bottom and help the millions fleeing conflict, poverty and disaster.

Please sign Oxfam’s petition calling on governments to find a global solution to tackle the refugee crisis or watch this short video, which explains what the campaign is about.

June 13, 2016

Meetings with Remarkable Women: Shen Ye, Organic Activist and Chinese Rock Chick

Last post from my recent visit to Beijing

If promoting organic farming through Oxfam partner Beijing Farmers Markets sounds a bit worthy, Shen Ye is

Shen Ye and me looking at beans

anything but – she’s one of the funniest people I’ve met in years and during a morning spent visiting farms on the outskirts of the City, was both fascinating and reduced me to repeated fits of giggles, with her mixture of Chinese magical realism and bawdy humour (some of it unrepeatable on a nice, decent blog like this one). Here’s a flavour.

In the cultural revolution, her grandfather survived because he was a much-loved local mayor and devout Communist with whom not even the Red Guards could find fault. He kept his son (Ye’s father) out of the Guards by apprenticing him to a painter who survived by painting murals of Chairman Mao up and down the land. That ensured food and survival, until he made a tragic mistake. He painted a picture on the back of an old poster of Mao, and the paint soaked through and disfigured the Great Leader. He was punished by being buried up to his waist in human excrement for days, until he eventually hanged himself.

On the road in the UK (geddit?). Shen Ye centre foreground.

His apprentice survived, but quit painting and rejected Communism. Essentially, he dropped out and ended up as a truckstop chef, specializing in turning the roadkill the truckers brought him into tasty dishes. But one day, when Ye was a young girl, the circus came to town and Ye’s dad fell in love with the high wire artist and disappeared. Following a tip, Ye eventually tracked him down and found he had retrained as a strongman, holding up bicycles with his teeth. At this point, I realized this was not going to be an ordinary conversation.

Ye left school at 17, worked as a maid for an old foreigner, and picked up excellent English. She ended up working for an independent rock band label managing Chinese rock bands. One even band toured the UK. Her most powerful memories are of the women of Newcastle. I won’t go into details, but suffice to say the sheltered young lads in her band never forgot the visit.

She ended up marrying a Brit from near Newcastle, who works in Beijing. They have a cat called Billy, who she  describes as a ‘Kitler’ (for obvious reasons – see pic). This despite her deep shock at the diet of the good people of England’s Northeast – she swears her husband only ate fresh vegetables when he reached adulthood (unless you count potatoes) – until then everything was tinned. As a typically food conscious-Chinese, she lasted 3 days and then insisted on taking over – she is now teaching her mother-in-law how to cook. They plan to move back to the UK and open an organic B&B in the sleepy coastal resort of Whitby. I hope Whitby’s ready for her.

describes as a ‘Kitler’ (for obvious reasons – see pic). This despite her deep shock at the diet of the good people of England’s Northeast – she swears her husband only ate fresh vegetables when he reached adulthood (unless you count potatoes) – until then everything was tinned. As a typically food conscious-Chinese, she lasted 3 days and then insisted on taking over – she is now teaching her mother-in-law how to cook. They plan to move back to the UK and open an organic B&B in the sleepy coastal resort of Whitby. I hope Whitby’s ready for her.

Hard to think of a better evocation of China’s extraordinary evolution over the last 50 years.

June 12, 2016

Links I Liked

I missed a week due to being in twitter-free Beijing, but now back in the warm and suffocating embrace of social media – here’s last week’s highlights

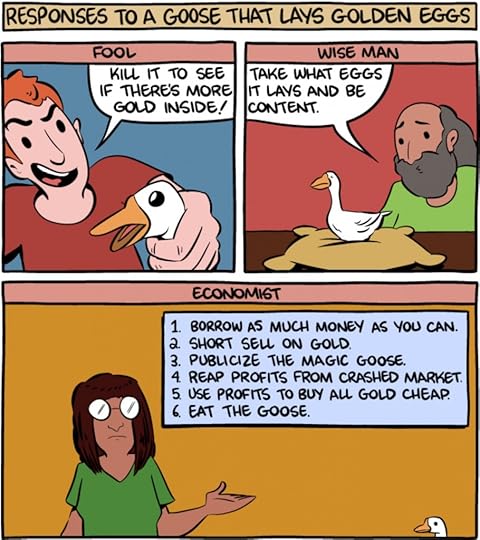

The goose that laid golden eggs. There’s fools, there’s wise men, and then there’s economists. Via Robert Went

Apparently, there’s an election coming up in the US…..

‘I have the best theories, I really do.’ Donald Trump as research scholar. This should become a thing – Donald Trump as job interviewee? Donald Trump as marriage guidance counsellor? Donald Trump as vicar?

Some heated debates on merits/otherwise of the newly annointed Democratic candidate for US president. Ezra Klein discusses the genius and gender issues in Hillary Clinton’s campaign & nomination. And if you’re just starting out, try listening to 21-year-old Hillary Rodham’s 1969 Wellesley commencement speech.

Will Hillary be heading for the safe centre ground? Not judging by this campaign video released on day she passed the finishing line for the nomination.

Over on this side of the pond, the level of rhetoric is rather less elevated. Here’s a handy interactive poll tracker on Britain’s Euro referendum, by demographics, geography, party etc. Why is Wales so anti EU when Scotland is so pro?

Back to aid and development

“The Worst Aid Project in the World” EU Support for Detention Camps in Sudan

Three reasons national organisations are vital to humanitarian response. Excellent real-life examples from South Sudan.

That iconic technophile story about fishermen using their mobile phones to find the best markets for their fish before they come ashore? Not true. Oops.

‘There are 27 countries where smoking rates went up 2000-2015′. World Bank overview in 5 charts of the world’s 1 billion smokers

10 things you should know about cash transfers, in a handy 4m animation – perfect for lectures, workshops etc

June 9, 2016

How Buddhist Tax Accountants and Whistle Blowers can change the world

Max Lawson is back again (he seems to have more time to write now he’s Oxfam International’s policy guy on inequality) to discuss tax morality and a bizarre encounter  with a Buddhist accountant

with a Buddhist accountant

A few years ago I went on a hiking holiday with a number of people I didn’t know, and ended up befriending a tax accountant. He was a very nice man, who had been going through a bit of a mid-life crisis, his children had grown up and left home, his wife was not very interested in him, and he had developed an interest in Buddhist philosophy. Anyhow, after a few days, he revealed to me that over the last five years he had started defrauding a firm he had been working for, to the tune of several million pounds a year. He was not taking the money for himself, but was abusing their trust in him, by not telling them about the latest tax avoidance schemes, meaning that they were systematically overpaying tax to the government.

I was reminded of this surprising suburban Robin Hood figure by the rash of stunning leaks on tax prompted by the whistle-blowers of the last couple of years, starting with the Luxleaks, then Swissleaks, and then the mother of all leaks, the Panama Papers. All have involved incredibly brave accountants or bankers risking a huge amount to get this information into the public domain. The two former employees of PricewaterhouseCoopers who leaked information on tax breaks for major corporates such as Apple, Ikea and Pepsi in the Luxleaks case are facing years in prison. The Swiss Leaks whistleblower has been sentenced to six years in prison in Switzerland in absentia. Finally the Panama Papers whistle blower has wisely remained anonymous, but I imagine is being hunted by a range of private security firms.

I was reminded of this surprising suburban Robin Hood figure by the rash of stunning leaks on tax prompted by the whistle-blowers of the last couple of years, starting with the Luxleaks, then Swissleaks, and then the mother of all leaks, the Panama Papers. All have involved incredibly brave accountants or bankers risking a huge amount to get this information into the public domain. The two former employees of PricewaterhouseCoopers who leaked information on tax breaks for major corporates such as Apple, Ikea and Pepsi in the Luxleaks case are facing years in prison. The Swiss Leaks whistleblower has been sentenced to six years in prison in Switzerland in absentia. Finally the Panama Papers whistle blower has wisely remained anonymous, but I imagine is being hunted by a range of private security firms.

I can only guess at the panic in the boardrooms of the investment banks and particularly at the big four accounting firms – Deloittes, PwC, KPMG and Ernst & Young, who between them have almost complete oversight over the business of aggressive tax planning by the major corporations. But no amount of security software can fully protect any firm from increasing numbers of employees no longer feeling morally comfortable with what they are doing, as ultimately the secrecy of the system is dependent on those that run it being able to look in the bathroom mirror in the morning and feel OK about their lives.

And that is becoming harder for the corporate tax accountant to do. A study for the New Economics Foundation from a few years ago calculated that for every £1 of value that a tax planner contributes to the UK economy, they take out £37. Imagine if we were employing thousands of people in the City of London to travel around the country and actually physically destroy public buildings; schools, hospitals; or sack teachers and nurses.

Like investment banking and arms dealing before it, tax planning for corporations and the wealthy has now passed the dinner party moment. Where before it would have prompted jokes about how boring it was, or perhaps even a slap on the back for enabling hard-pressed entrepreneurs to escape the clutches of the dastardly taxman, it is now rapidly becoming seen as not a profession that is not one you would care to shout about. How many young graduates would want to help Starbucks or Google pay zero tax?

the dinner party moment. Where before it would have prompted jokes about how boring it was, or perhaps even a slap on the back for enabling hard-pressed entrepreneurs to escape the clutches of the dastardly taxman, it is now rapidly becoming seen as not a profession that is not one you would care to shout about. How many young graduates would want to help Starbucks or Google pay zero tax?

Also like investment banking, tax accountants engaged in the kind of aggressive tax avoidance for the super wealthy and multinational corporations are a relatively small proportion of the profession, and risk dragging the whole accountancy profession into the mud with their semi-illegal activity. This is deeply embarrassing for all the tens of thousands of accountants out there who are doing a good job enabling ordinary people, charities and small companies to manage their finances and pay their taxes.

The philosopher Michael Sandel, in his fantastic book, ‘What Money Can’t Buy: the Moral Limits of Markets’ points out that we have in recent years begun to move from a market economy to a market society, where not just our economy but our moral values are now increasingly only defined by a market logic. He believes this has undermined our morality and societies. I think the tax issue is a fine example of this. Using the market moral logic of the age, there is nothing wrong with aggressive tax competition between nations, nothing wrong with the network of financial secrecy and bevy of accountants, lawyers and enablers who keep the whole thing going. It is helping markets function more efficiently, which is ultimately good for all of us. On tax I believe we have reached a turning point, with the public rejecting this logic. Polling from across the political spectrum shows that people now believe both legal and illegal tax avoidance to be wrong.

I don’t think suddenly every tax accountant is going to quit, or that every graduate is going to resist the allure of the graduate training programme at one of the Big Four firms, especially when they are laden with debts from their studies. Certainly the arms and investment banking businesses are flourishing despite becoming morally questionable professions. They must just go to dinner parties with each other these days.

I don’t think suddenly every tax accountant is going to quit, or that every graduate is going to resist the allure of the graduate training programme at one of the Big Four firms, especially when they are laden with debts from their studies. Certainly the arms and investment banking businesses are flourishing despite becoming morally questionable professions. They must just go to dinner parties with each other these days.

But I do know that the tax haven and tax dodging business is quite special in that it is completely reliant on secrecy, so we don’t need every accountant to have a Saul to Paul conversion. All we need is five or ten more whistle-blowers and the whole system will be on its knees. And in the interim, I would appeal to all the other tax planning accountants out there, who like me have a mortgage and children and would never be brave enough to risk everything. Why not follow my friend’s example instead, and just do your jobs not so well? Fail to tell you client about the latest ruse. Fail to save them that extra couple of percent. A work to (moral) rule? Every penny counts.

June 8, 2016

Where have we got to on adaptive learning, thinking and working politically, doing development differently etc? Getting beyond the People’s Front of Judea

Props to Dave Algoso (left) and Alan Hudson at Global Integrity for making the effort to compare and contrast 9 different initiatives that are all heading in roughly the right direction in reforming aid

Props to Dave Algoso (left) and Alan Hudson at Global Integrity for making the effort to compare and contrast 9 different initiatives that are all heading in roughly the right direction in reforming aid

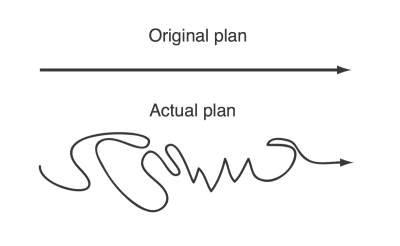

Aid, development, and governance practitioners increasingly recognize that change happens through iterative processes (trying, learning, adapting the approach taken, and trying again) as opposed to the linear assumptions that underpin much of the sector (do more X, get more Y). Pre-planned, linear, blueprint approaches to change fail in the face of contextual variations and shifting political interests. Progress occurs when efforts are more adaptive.

Several recent initiatives have brought together practitioners, policymakers, researchers, and others. Having multiple efforts as part of a movement can be very powerful, but the lines between these initiatives can be blurry; their missions, approaches, and stakeholders all overlap. As a result, there is a risk that participants in these initiatives end up unnecessarily splintering in competition over jargon and brand position (think Monty Python’s

Are we DDD or TWP today?

To help clarify the overlaps and differences, we’ve compared nine different initiatives. Important caveats: This is non-rigorous and each initiative is evolving, with multiple stakeholders involved, such that pinning down the essence or core strategy of each is nearly impossible. But we are sharing the general gist of each based on our informal observations.

Each initiative in brief

Let’s tackle them in batches of three, moving from the general to the specific.

Across the whole development sector

Initiative

What is it?

Doing Development Differently (DDD)

Community of researchers and practitioners convened by the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) and Harvard’s Kennedy School. Has a core manifesto calling for development to focus on locally defined problems, tackled through iteration, learning, and adaptation.

Thinking and Working Politically (TWP)

Semi-regular convening of representatives from various donors, think tanks, and international NGOs that discusses the use of politically aware approaches to aid and development.

Global Delivery Initiative (GDI)

Cross-donor collaborative (spearheaded by the World Bank, which currently serves as the Secretariat) to deepen the know-how for effective operational delivery of aid and development.

Focused on governance and accountability

Initiative

What is it?

Global Partnership for Social Accountability (GPSA)

Funds and convenes CSOs and governments on social accountability initiatives. Established by the World Bank in 2012.

Making All Voices Count (MAVC)

Five-year program (2013-2017) funded by multiple donors (DfID, USAID, Sida, and Omidyar) to find, fund, and learn from innovations that support accountable governance.

TA LEARN

Community of practice composed of transparency and accountability practitioners from many countries.

Focused on targeted aspects of the aid/development sector (but not governance/accountability)

Initiative

What is it?

ADAPT(analysis driven agile programming techniques)

Collaboration of two major NGOs (Mercy Corps and International Rescue Committee) to identify, develop, and spread the use of adaptive management approaches in complex aid and development projects.

Smart Rules

DfID’s internal operating framework for programs, emphasizing how the agency adapts to and influences local context. Rolled out in 2014.

Collaborating, Learning, and Adapting (CLA)

USAID’s framework and internal change efforts for incorporating collaboration, learning, and adaptation at its missions and implementing partners.

What we left out: This list is hardly exhaustive: among others, we left out Feedback Labs (focused on the specific issue of citizen/beneficiary feedback), Principles for Digital Development (guidelines for integrating technology into development programs), and the Open Government Partnership (multi-stakeholder initiative to open government).

Actors: Who’s involved with each?

Many of the actors in these initiatives overlap, which has provided some cross-pollination of ideas. Researchers and think tanks (especially ODI) have been active in all of these initiatives. But it’s the mix of ownership by donors and practitioners that most shapes each initiative.

Mixed stakeholders: The governance/accountability initiatives (TA LEARN, GPSA, and MAVC) all have mixes of actors from multiple countries, though naturally most partners work in related issues such as open governance, transparency, citizen engagement, etc. The DDD community has a similar mix, with a slightly broader set of issues represented (though most of their work is still grounded in governance, institution-building, service delivery, or policy reform).

Leaning toward the donor side: Three of these initiatives are heavily anchored in donor agencies: CLA at USAID, Smart Rules at DfID, and GDI at the World Bank.

Implementer-focused: The ADAPT initiative is the only one led by and focused on non-donor agencies, in particular the IRC and Mercy Corps, though they have also engaged donors and others through pilot projects and events.

Focus: How central is adaptive learning? And working politically?

These initiatives see adaptive learning in different ways. To some, it’s a central driver of how change happens and a core strategic pillar. Others use adaptive learning more tactically, as a way to improve traditional approaches on the margins.

We see this as closely related to another concept: the political nature of development. Especially in governance and accountability work, navigating the fog of political interests—both hard to discern and likely to shift—is one of the core reasons why adaptive learning is so critical.

However, these initiatives don’t promote both concepts equally. We can expand on a spectrum that Duncan previously shared for TWP (from “evolutionary” to “revolutionary” uptake) into two dimensions.

Activities: What does each initiative do?

These initiatives’ strategies—whether explicitly stated or inferred from their activities—fall into four general approaches:

Practices: Identifying, developing, and sharing cases, methods, and tools. Nearly all of these initiatives have developed sets of case studies, framed with necessary context (organizational, political, etc), as an antidote to the reductive tendency of “best practices”.

Principles: Thought leadership, conceptual framing, and evidence. Nearly all of these initiatives are also working to provide the terminology and frameworks for furthering ideas.

Community: Cross-organization network building. Conferences and workshops create space for sharing practices and testing frameworks. Only GPSA and CLA actively encourage virtual exchanges separate from physical meetings.

Reform: Internal change at lead partner(s). ADAPT, CLA, and GDI all pair internal change at their lead organizations with external changes in the sector. Smart Rules has an exclusively internal focus.

One approach seems relatively underutilized: Only GPSA and MAVC make grants of any kind to support project implementers who are developing practices. (Though some of the other initiatives also fund research.)

One approach seems relatively underutilized: Only GPSA and MAVC make grants of any kind to support project implementers who are developing practices. (Though some of the other initiatives also fund research.)

Conclusions (?): Where do we go from here?

First, we need clearer examples of adaptive learning in practice. We have a growing set of case studies, but few include a compelling counterfactual for what would have happened in the absence of adaptation.

Second, making the case with counterfactuals requires a bit more conceptual clarity. It’s not clear that we’re always talking about the same thing when we discuss “adaptation”, “learning”, or “working politically”. We need to clarify how adaptive learning leads to change.

Relatedly, one of the key concepts requiring clarification involves ownership over learning and adaptation. Despite the mix of stakeholders involved in these initiatives, few meaningfully distinguish between learning by external actors and by local actors, and the ways one can support the another.

Finally, this mapping suggests a potential for greater connectivity across the initiatives. There are some actors  overlapping several of these, but there were significant gaps until literally just a few months ago. Unfortunately, this is tied up a bit in issues of organizational ownership: some initiatives are only weakly owned, with no steering hand from the lead organizations, while others are so identified with a single organization as to leave others with no entry point. Efforts pushing the sector in broadly the same direction should push together.

overlapping several of these, but there were significant gaps until literally just a few months ago. Unfortunately, this is tied up a bit in issues of organizational ownership: some initiatives are only weakly owned, with no steering hand from the lead organizations, while others are so identified with a single organization as to leave others with no entry point. Efforts pushing the sector in broadly the same direction should push together.

Please let us know what you think of this mapping. This was not designed as a rigorous final say on these initiatives, but rather as a conversation starter. What did we get wrong? What did we leave out? Is it worth building on this with a more rigorous and perhaps broader version? Would a one-stop shop, or regular updates on what’s going on in the various initiatives, be of use?

June 7, 2016

How does Change Happen in China?

The honest answer is of course that I have no idea. Given China’s size, complexity, opacity and the language barrier  created by being a non-mandarin speaker, a week of meetings and conversations can only leave a string of vague and often contradictory impressions. But here they are anyway:

created by being a non-mandarin speaker, a week of meetings and conversations can only leave a string of vague and often contradictory impressions. But here they are anyway:

Is China’s development complex or complicated? The standard account of China’s extraordinary transformation is of a triumph of Central Planning – in the late 1970s, a dominant Communist Party decided to go for it, initiated a market transformation and…. boom! That would fall under the ‘complicated’ label. But in a panel on How Change Happens, long time China watcher Richard Carey reckoned differently – he argued that it’s more accurate to see China as an entrepreneurial, evolutionary economy in which lots of random variations and local experiments emerge. To stick with evolutionary terminology, the genius of the government has been in then selecting and amplifying the fit variants such as the Township and Village Enterprises.

That fits with another recurring theme – the importance of pilots to test ideas on the ground, and in order to convince officials to adopt this or that approach. Whether inside or outside government, everyone talks about pilots all the time. That interest in evidence is reflected in the increasingly dense network of thinktanks and universities, many of them either run by, or closely connected to, the state. If you want to influence policy in China, you need to get your facts right, and link in with these conversations as deeply as possible.

I was also struck by the importance of scandals and test cases in changing government policy. A visit to a migrant-run museum of migration showed that a 2003 scandal in which a migrant was beaten to death while in detention transformed the government approach – migrants’ lives remained hard, but the level of arbitrary abuse declined sharply. On gender-based violence, a number of influential legal test cases, including against professors accused of sexually harassing their students, led to major policy changes by both government and corporates.

I was also struck by the importance of scandals and test cases in changing government policy. A visit to a migrant-run museum of migration showed that a 2003 scandal in which a migrant was beaten to death while in detention transformed the government approach – migrants’ lives remained hard, but the level of arbitrary abuse declined sharply. On gender-based violence, a number of influential legal test cases, including against professors accused of sexually harassing their students, led to major policy changes by both government and corporates.

International attention also helps. Women’s rights activists identify the impending 20th anniversary of the 1995 Beijing conference on women as the turning point in the passing of an Anti-Domestic Violence Law in 2015 even though the dogged persistence of Chinese women’s rights NGOs also played a big part (‘without NGOs there would be no national law, or it would have taken much longer’).

In a country of the size and power of China, change is primarily endogenous, the result of interactions between and within the state, citizens and private sector. The government, while hugely powerful, is not a monolith, and understanding the relationships between different ministries, tiers of government etc, is at the heart of any attempt to understand (let alone influence) how change happens. The improvements between the penultimate and final drafts of the new Overseas NGO Management law largely came about because of pressure from ministries such as health or education, who were concerned about its impact and enforceability. Concerns over China’s international reputation and exchanges with other governments and  international networks may also have helped, although we’ll never really know.

international networks may also have helped, although we’ll never really know.

Whether in the case of the Anti-Domestic Violence or Overseas NGO laws, I was told, ‘most law in China is just principles. What matters is implementation, enabling regulations, judicial explanations, ministerial guidelines or province-level action.’ A lot of the hard graft of influencing takes place at this more technical, below-the-radar level, for example drafting guidelines or running pilots to show how laws can best be implemented. And as anywhere, building personal trust is essential ‘we take part in family occasions, eg attend funerals – friendship and relationships matter.’

‘Anything can be changed, even in China’ concludes one strikingly optimistic and experienced advocate, but it certainly isn’t easy. To stay afloat, NGOs need enormous reserves of political acumen, connections and stamina.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers