Duncan Green's Blog, page 141

June 6, 2016

What’s happening to inequality in China? Update from a visit to Beijing

Spent a fascinating few days in Beijing last week, at the invitation of Oxfam Hong Kong. The main topic was inequality, including a big seminar with lots of academics (NGOs are very research-based in China – it was a graphtastic, PhD-rich week). Here are some of the headlines:

Spent a fascinating few days in Beijing last week, at the invitation of Oxfam Hong Kong. The main topic was inequality, including a big seminar with lots of academics (NGOs are very research-based in China – it was a graphtastic, PhD-rich week). Here are some of the headlines:

Income Inequality in China is changing fast. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, the Gini index peaked in 2008 and has fallen back since (see graph – and note it only starts in 2003, so omits the big rise in the gini before that date). But before we declare victory, there are three big caveats:

Measurement: the index is based on the NBS’ annual survey of 140,000 households. The problem with that, as Thomas Piketty pointed out in his LSE talk, is that it misses the very wealthy households, and so underestimates overall inequality. According to the top Chinese inequality guru, Li Shi (who’s is speaking in London this afternoon, at a King’s College event), tax data is also unreliable (even if the government was willing to release it) as fewer and fewer people report their real income.

Urban v Rural: confusingly, income inequality is actually rising within urban areas, and within rural areas, even as it falls overall. This apparently contradictory effect is because the gap between urban and rural areas has been shrinking, as the government has given priority to pushing industry, jobs and public spending inland. It’s a bit like the global picture, where the Global Gini is falling because of the rise of China even as many/most countries experience rising within-country inequality.

This means that China is undergoing a shift from horizontal inequality (between groups, in this case regions) to vertical inequality (between individuals). As Frances Stewart has shown, these two kinds of inequalities typically produce different social effects – horizontal inequality often leads to conflicts, civil wars between powerful and excluded groups etc, whereas vertical inequality is more likely to trigger social breakdown as the poor start taking redistribution into their own hands. Given the Chinese government’s concern with stability and social cohesion, its increasing focus on inequality makes a lot of sense.

Wealth inequality is rising incredibly fast, largely driven by China’s massive housing bubble. The bar chart shows the extraordinary rise in the assets of the richest 10% of Chinese over just the 8 years to 2010 (and the bubble has continued since then). Thanks to rising rents and capital gains when people sell their houses, the bubble is also responsible for about a third of the rise of urban income inequality, according to Li Shi. One Piketty-esque solution would be to introduce property or inheritance taxes but that is likely to run into opposition from the people with the big houses, and in any case could burst the bubble, precipitating a property crash with disastrous wider effects on the economy.

Wealth inequality is rising incredibly fast, largely driven by China’s massive housing bubble. The bar chart shows the extraordinary rise in the assets of the richest 10% of Chinese over just the 8 years to 2010 (and the bubble has continued since then). Thanks to rising rents and capital gains when people sell their houses, the bubble is also responsible for about a third of the rise of urban income inequality, according to Li Shi. One Piketty-esque solution would be to introduce property or inheritance taxes but that is likely to run into opposition from the people with the big houses, and in any case could burst the bubble, precipitating a property crash with disastrous wider effects on the economy.What to do? The government plans to continue to extend the social security system within rural areas, which has expanded massively in recent years. It also says it will reform the hukou system, which restricts migration and condemns migrant workers from rural areas into second-class citizens in the cities. I spent an afternoon with an Oxfam partner, the Beijing Migrant Workers’ Home to get a better feel for the hukou system. Set up by Sun Heng, a migrant street musician, the Centre has set up a cinema, theatre and even a museum, as well as building a school for migrant workers’ kids who are excluded from the public system. Enough text, here are a couple of short video clips with my impressions, and some views from the Home’s Lü Tu.

Finally, a rather interesting idea came up which I said I would ask around about. Inequality data is much more unreliable and patchy than income data. Could Big Data help? Has anyone thought about how to use Big Data either to fill in the gaps in household surveys (mentions of BMWs or champagne on social media as a proxy for high end consumption? Only half joking – you get the idea), or to do something in realtime on rising and falling inequality in different regions? Would love to hear what’s going on, as would the researchers in Beijing, because while the government may be tight-lipped, there is lots of access to data from China’s hyper-vibrant social media users.

June 5, 2016

First inequality, now neoliberalism: how many statues are left to kick over outside the IMF?

Max Lawson, now Oxfam International’s policy guy on inequality, shares his newfound love for an old foe

Last week the IMF published an article in its magazine that caused a considerable stir around the world. Entitled ‘Neoliberalism: oversold?’ the short piece by Jonathan D. Ostry, Prakash Loungani, and Davide Furceri, all from the Fund’s Research Department, questions whether the economic approach of neoliberalism has been taken too far. They define neoliberalism as a focus on promoting competition through deregulation and on shrinking the state through privatisation and fiscal austerity.

The authors conclude that many of the policies promoted under the neoliberal approach have been beneficial to economic progress. Among these they list the privatisation of state owned enterprises, and the expansion of global trade. However, they argue that others have been of more questionable benefit. Among these they include liberalising the flows of international capital, to allow speculative money to flow in and out of countries rapidly, which they conclude is largely harmful, and austerity, which they believe whilst necessary in some circumstances due to high debt burdens, is nevertheless dangerous in that it increases inequality, which in turn reduces growth.

These conclusions from the IMF are very welcome and it is to be congratulated. They come from the same team that has also recently led research that found that trade unions are important to rebalancing the proceeds of growth away from capital towards labour, thus making it more equitable; that inequality is not harmed by redistributive policies in many instances; and that inequality can be harmful to both the level and duration of economic growth. It would be hard to find a statue anywhere in the vicinity of the IMF building that has not been kicked over by these guys.

These conclusions from the IMF are very welcome and it is to be congratulated. They come from the same team that has also recently led research that found that trade unions are important to rebalancing the proceeds of growth away from capital towards labour, thus making it more equitable; that inequality is not harmed by redistributive policies in many instances; and that inequality can be harmful to both the level and duration of economic growth. It would be hard to find a statue anywhere in the vicinity of the IMF building that has not been kicked over by these guys.

And this latest statue is important, as it is a key causal factor underpinning many of these other concerns, helping understand the trend towards increasing inequality. Neoliberalism, or Market Fundamentalism as figures like the Governor of the Bank of England have called it more recently, is something activists have consistently identified as a leading factor behind the growing gap between rich and poor across the world. It works in many ways. Neoliberalism underpins the relentless pressure for ‘more flexible labour markets’, which has led to the decline in trade union power, decline in wages and a much greater proportion of growth ending up in the hands of the owners of capital. Privatisations of state assets, while another neoliberal mainstay, are behind many of the huge billionaire fortunes of the 62 richest in the world, from Mexico’s Carlos Slim to the oligarchs of Russia.

The deregulation of the financial sector was also linked to the neoliberal agenda. Banks have led the way in a new era of record highs in profits, executive pay and bonuses, all of which have helped fuel inequality. While not the explicit intention of many of the architects of neoliberalism, the focus on deregulation and minimal government oversight has  in turn opened the door to corruption and political capture by elites. This political capture of the controlling levers of the economy, to the benefit of the 1%, is another causal factor in the inequality story. The same financial deregulation and ‘race to the bottom’ tax competition between countries has created the network of secrecy jurisdictions and tax havens exposed by the Panama Papers, which are enabling widespread corruption and channelling wealth upwards.

in turn opened the door to corruption and political capture by elites. This political capture of the controlling levers of the economy, to the benefit of the 1%, is another causal factor in the inequality story. The same financial deregulation and ‘race to the bottom’ tax competition between countries has created the network of secrecy jurisdictions and tax havens exposed by the Panama Papers, which are enabling widespread corruption and channelling wealth upwards.

The privatisation of public services, where access to healthcare, or the ability to learn, is increasingly based on the ability to pay, again has its roots in neoliberal thinking. This too has been shown to be harmful to social mobility and stifles opportunity, as it excludes the poorest from health and education, and in turn increases inequality.

The Guardian portrayed the article as a sign that we have perhaps past ‘peak neoliberal’ and witnessing ‘the long slow death’ of this way of thinking. The IMF article has clearly rattled the Financial Times, who sought to dismiss it in a way that I found a bit desperate. Certainly with ordinary people, the neoliberal worldview, although rarely called that any more, is pretty unpopular. Right wing populists like Donald Trump are railing against globalisation as much as socialists like Bernie Sanders. But at the moment there is no unified alternative on offer, with protest fragmenting to the right and left. It is also an extremely powerful and tenacious worldview within elites across the world. Small wonder, in that it has served them very well indeed.

For many, particularly in the developing world, the IMF itself has long been a byword for neoliberalism – if anyone was doing the overselling of neoliberalism for many years, it was the Fund. In fact it wasn’t really selling so much as ransoming. The damage done in the 1990’s and 2000’s by the imposition of neoliberal policies was dramatic and had a high human cost in countries across the world. And there remains a big gap today between the great research coming out of the IMF and the continued actions of the IMF on the ground.

For many, particularly in the developing world, the IMF itself has long been a byword for neoliberalism – if anyone was doing the overselling of neoliberalism for many years, it was the Fund. In fact it wasn’t really selling so much as ransoming. The damage done in the 1990’s and 2000’s by the imposition of neoliberal policies was dramatic and had a high human cost in countries across the world. And there remains a big gap today between the great research coming out of the IMF and the continued actions of the IMF on the ground.

So all the more impressive then that the IMF has chosen to publish this article at this time. I hope that this is the beginning of more research and analysis by the Fund on neoliberalism and its impacts. This is a major contribution to the much-needed debate on how we tackle the causes of the inequality crisis and build more equitable growth that benefits the majority, not simply a tiny minority at the top.

June 2, 2016

The 2016 Multidimensional Poverty Index was launched yesterday. What does it say?

This is at the geeky, number-crunching end of my spectrum, but I think it’s worth a look (and anyway, they asked  nicely). The 2016 Multi-Dimensional Poverty Index was published yesterday. It now covers 102 countries in total, including 75 per cent of the world’s population, or 5.2 billion people. Of this proportion, 30 per cent of people (1.6 billion) are identified as multidimensionally poor.

nicely). The 2016 Multi-Dimensional Poverty Index was published yesterday. It now covers 102 countries in total, including 75 per cent of the world’s population, or 5.2 billion people. Of this proportion, 30 per cent of people (1.6 billion) are identified as multidimensionally poor.

The Global MPI has 3 dimensions and 10 indicators (for details see here and the graphic, right). A person is identified as multidimensionally poor (or ‘MPI poor’) if they are deprived in at least one third of the dimensions. The MPI is calculated by multiplying the incidence of poverty (the percentage of people identified as MPI poor) by the average intensity of poverty across the poor. So it reflects both the share of people in poverty and the degree to which they are deprived.

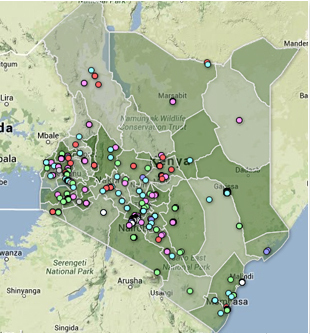

The MPI increasingly digs down below national level, giving separate results for 962 sub-national regions, which range from having 0% to 100% of people poor (see African map, below). It is also disaggregated by rural-urban areas for nearly all countries as well as by age.

Headlines from the MPI 2016:

There are 50% more MPI poor people in the countries analysed than there are income poor people using the $1.90/day poverty line.

Almost one third of MPI poor people live in Sub-Saharan Africa (32.%); 53% in South Asia, and 9% in East Asia.

As with income poverty, three quarters of MPI poor people live in Middle Income Countries.

This year’s MPI focuses on Africa:

In the 46 African countries analysed, 544 million people (54% of total population) endure multidimensional poverty, compared to 388 million poor people according to the $1.90/day measures.

The differences between the proportion of $1.90 and MPI poor people are greatest in East and West Africa. By the $1.90/day poverty line, 48% in West Africa and 33% in East Africa are poor, whereas by the MPI, 70% of people in East Africa are MPI poor and 59% in West Africa. The MPI thus reveals a hidden face of poverty that may be overlooked if we consider only its income aspects.

Among 35 African countries where changes to poverty over time were analysed, 30 of them have reduced poverty significantly. Rwanda was the standout star, but every MPI indicator was significantly reduced in Burkina Faso, Comoros, Gabon and Mozambique as well.

Among 35 African countries where changes to poverty over time were analysed, 30 of them have reduced poverty significantly. Rwanda was the standout star, but every MPI indicator was significantly reduced in Burkina Faso, Comoros, Gabon and Mozambique as well.Disaggregated MPI results are available for 475 sub-national regions in 41 African countries. The poorest region continues to be Salamat in Chad, followed by Est in Burkina Faso and Hadjer Iamis in Chad. The region with the highest percentage of MPI poor people is Warap, in South Sudan, where 99% of its inhabitants are considered multidimensionally poor. The least poor sub-national regions include Grand Casablanca in Morocco and New Valley in Egypt, with less than 1% of the population living in multidimensional poverty.

The MPI registered impressive reductions in some unexpected places. 19 sub-national regions – regional ‘runaway’ successes – have reduced poverty even faster than Rwanda. The fastest MPI reduction was found in Likouala in the Republic of the Congo.

The Sahel and Sudanian Savanna Belt contains most of the world’s poorest sub-regions, showing the interaction between poverty and harsh environmental conditions.

Poverty looks very different in different parts of the continent. While in East Africa deprivations related to living standards contribute most to poverty, in West Africa child mortality and education are the biggest problems.

The deprivations affecting the highest share of MPI poor people in Africa are cooking fuel, electricity and sanitation.

The number of poor people went down in only 12 countries. In 18 countries, although the incidence of MPI fell, population growth led to an overall rise in the number of poor people.

See here for my post on the MPI 2014. I’d be interested in your reflections on what MPI adds to the usual $ per day metrics, in terms of our understanding of development.

June 1, 2016

Community Philanthropy: it’s a thing, and you need to know about it

Guest post from Jenny Hodgson of the Global Fund for Community Foundations

It’s almost always the same argument. Or excuse. Governments joining the accelerating global trend of restricting civil society at home like to claim that they are protecting their country against meddling “foreign powers”.

No one has to like, or agree, with that point of view in order to take it seriously, and perhaps even to see the onslaught as an opportunity. As the saying goes, a crisis is a terrible thing to waste.

The assaults on civil society globally—as outrageous as they are—could help to provoke a hard look at the prevalent model of external funding, particularly of human rights and social justice issues. Why, when we all agree that developing country governments weaning themselves off aid and raising more domestic resources is a good thing, do aid donors and activists not apply the same logic to Civil Society Organizations (CSOs)?

Luckily, the world isn’t waiting for the aid business to wake up. For some years now, aid from international donors has no longer been the only “show in town”. Development funding is already starting to diminish or to become more directly associated with countries’ commercial interests. And, at the same time, local philanthropic sectors are emerging in many parts of the world that were traditionally considered purely “aid

Luckily, the world isn’t waiting for the aid business to wake up. For some years now, aid from international donors has no longer been the only “show in town”. Development funding is already starting to diminish or to become more directly associated with countries’ commercial interests. And, at the same time, local philanthropic sectors are emerging in many parts of the world that were traditionally considered purely “aid

KCDF grants map

recipient” countries. The super-wealthy are establishing their own foundations (although relatively few are yet interested in achieving their mission through grants to civil society) and many of these already overtake their European and North American peers in asset size (such as in China). And in many countries, a growing middle class has its own disposable income, and an increasing appetite for giving to social causes.

Raising money locally can be hard work. It’s far easier, of course, to submit a proposal to an eager external donor who shares your goals, and, let’s not deny it, your jargon.

But local funding is not just about the money. It is a crucial—and sadly overlooked—part of a larger political strategy for constituency building, for getting people to learn and care about your cause, so that when your organization is threatened with closure, there are people in the community that may actually speak up. Just as taxation strengthens the social contract citizens and states, local fundraising can improve the accountability of CSOs to the people they serve.

Shifting the balance of funding power (because yes, it is power, even if we consider it to be “good” power) from international to local is going to be a long, and inevitably slow process. But there is already a growing set of institutions to learn from in the global South—including community foundations, community philanthropy organizations, women’s funds and other types of local grassroots grantmakers. These include the Kenya Community Development Foundation, Instituto Rio in Brazil, India’s Foundation for Social Transformation and the Waqfeyat al  Maadi Community Foundation in Egypt.

Maadi Community Foundation in Egypt.

This new generation of organizations constitutes an essential, but often missing piece, not just of civil society architecture but also of healthy, inclusive communities. They put together local and external cash under a single institutional roof, in order to give small grants to local groups through open calls for submissions, acting as a counter (or complement) to local level government institutions.

The way such organizations are governed is crucial to their wider impact. They seek to be reflective of their communities in the composition of their boards, pitching their institutional tent as broadly as possible to maximize both ownership and potential for resource mobilization. In this way, they can bring the diversity of communities’ interests together “in-house” and draw in and on different perspectives. Participatory grant-making, where communities themselves are involved in decisions around resource allocation, is another important feature of this field. It’s hard and labour-intensive work, particularly when communities have never been asked to make such choices before, but essential if power is really going to be shifted.

Over the past ten years, my organization, the Global Fund for Community Foundations has sought to increase recognition and mutual support for this fledgling movement, building up a network of over 160 community philanthropy organizations in more than 60 countries: while each organization looks different, what unites them as a group is a core belief that development will be stronger and more lasting when local people see themselves as co-investors and participants. And yes, it turns out that when a funding base is made up of lots of different contributions from local sources, it is often able to address sensitive issues that might get organizations that are entirely dependent on external funding into serious hot water.

Community foundations in Central and Eastern Europe, for example, have started to engage around issues affecting the Roma and, even more recently, around refugees from Syria. That wouldn’t be possible without the trust and reputation they had accumulated by working across a range of other local issues for many years. In other parts of the world, our partners are tackling other hot potatoes such as migrant labour, the environment and peace-building.

Community foundations in Central and Eastern Europe, for example, have started to engage around issues affecting the Roma and, even more recently, around refugees from Syria. That wouldn’t be possible without the trust and reputation they had accumulated by working across a range of other local issues for many years. In other parts of the world, our partners are tackling other hot potatoes such as migrant labour, the environment and peace-building.

For donors, this is not about a call to back off, but rather to think and fund differently, to realize both the power and the limitations of their support and to engage in some serious reflection as to the kind of long-term footprint that they want to leave behind them. In short:

Local, people-centred institutions matter. International development needs local NGOs but when they are shaped too much by external funding they might not be the kinds of organizations that local people actually want. Local civil society organisations can play an important role in negotiating with other institutional players (state, corporate etc.) but their ability to do so also depends on some degree of legitimacy and local buy-in – and perhaps not looking just like mirror images of their funders.

Communities have assets but too often they are overlooked in the development equation. And local giving equates to social capital and trust, something that is almost impossible to build from the outside.

Finally, building local philanthropy is a slow, painstaking process: external donors can play a critical role in

providing matching and core funding. And they also have much to gain by working with local partners who can target grants and other supports deep into communities that are normally beyond the reach of external donors.

providing matching and core funding. And they also have much to gain by working with local partners who can target grants and other supports deep into communities that are normally beyond the reach of external donors.This is a difficult, soul-searching time for civil society and donors alike. Community philanthropy cannot provide all the answers. But the field offers some important insights into how to build a more democratic, respectful and resilient (both politically and financially) foundation for the exercise of active citizenship.

May 31, 2016

Conference rage and why we need a war on panels

Today’s post definitely merits a vlog – apologies for quality (must get a decent camera)

With the occasional exception (see yesterday’s post on Piketty), my mood in conferences usually swings between boredom, despair

Money well spent?

and rage. The turgid/self-aggrandizing keynotes and coma-inducing panels, followed by people (usually men) asking ‘questions’ that are really comments, usually not on topic. The chairs who abdicate responsibility and let all the speakers over-run, so that the only genuinely productive bit of the day (networking at coffee breaks and lunch) gets squeezed. I end up dozing off, or furiously scribbling abuse in my notebook as a form of therapy, and hoping my neighbours can’t see what I’m writing. I probably look a bit unhinged…..

This matters both because of the lost opportunity that badly run conferences represent, and because they cost money and time. I guess if it was easy to fix, people would have done so already, but the format is tired and unproductive – how can we shake it up?

Recognise this?

Some random thoughts and suggestions to get the ball rolling:

Conferences frequently discuss evidence and results. So where are the evidence and results for the efficacy of conferences? Given the resources being ploughed into research on development (DFID alone spends about £350m a year), surely it would be a worthwhile investment (if it hasn’t already been done) to sponsor a research programme that runs multiple parallel experiments with different event formats, and compares the results in terms of participant feedback, how much people retain a month after the event etc? At the very least, can they find or commission a systematic review on what the existing evidence says?

Feedback systems could really help: A public eBay-type ratings system to rank speakers/conferences would provide nice examples of good practice for people to draw on (and bad practice to avoid). Or why not go realtime and encourage instant audience feedback? OK, maybe Occupy-style thumbs up from the audience if they like the speaker, thumbs down if they don’t would be a bit in-your-face for academe, but why not introduce a twitterwall to encourage the audience to interact with the speaker (perhaps with moderation to stop people testing the limits, as my LSE students did to Owen Barder last term)?

How did something as truly awful as panel discussions become the default format? People reading out papers; terrible powerpoints crammed with too many words, or illegible graphics. Please, can we try other formats, like speed dating (eg 10 people pitch their work for 2 minutes each, then each goes to a table and the audience hooks up (intellectually, I mean) with the ones they were interested in); world cafes; simulation games; joint tasks (eg come up with an infographic that explains X). Anything, really. Yes ‘manels’ (male only panels – take the pledge here) are an outrage, but why not go for complete abolition, rather than mere gender balance?

We need to get better at shaping the format to fit the the precise purpose of the conference. If it’s building networks,

Take the pledge, dudes

making new links etc, then you need to maximise the interaction time – speed-dating, lots of coffee breaks etc. If it’s to jointly progress thinking on a particular issue, then use a workshop methodology, like the excellent USAID/IDS seminar I attended a few months ago (whose results I’m still using). If it’s to pick apart and improve methods and findings, then it has to be at first draft stage, and with the right combination of academics and practitioners in the room. But if the best you can manage is ‘disseminating new research’ of ‘information sharing’, alarm bells should probably ring.

Resource it: Organizing good conferences requires expertise and time. It’s not something an overburdened academic should be doing at 1am, after the kids are in bed, and the emails are done. Weirdly, friends tell me that there is often no budget for conferences. But doing them on the cheap is a false economy, if all the people who end up the room wish they were dead/get nothing out of it. So research funders should demand a sensible conference budget in any proposal, and outside particular research projects, academic institutions should fund conferences seriously as places where networking can incubate new ideas and refine old ones.

And why should academics be organizing them anyway? Isn’t there a case for outsourcing more of them to good good conference organizers who ‘get’ the special challenges of academic (rather than, say, corporate) events?

Anyone read this?

With my How Change Happens hat on, the obvious question is, why haven’t things changed already? Using the handy 3i rule of thumb, is it ideas, institutions or interests that are keeping things this way?

Ideas: maybe people genuinely think this format is the best possible, or just lack imagination – how do we undermine that view and get recognition of alternatives?

Institutions: is part of the reason for the leaden, top-down formats that organizers want to control the agenda, pump out their own material etc? Does everyone need to be on a platform, with at least 20 minutes to talk about themselves or their interests? If so, very hard to get away from panelism.

Interests: Academics have to write papers for career advancement and to feed the REF beast. But does that really mean they have to present and discuss them in such a mind-numbing way?

Finally, allow me one unconstructive suggestion: can we please as standard have a clock above the platform that not only records the time, (for the benefit of the chair), but the cumulative cost of the day, based on a rough estimate of the hourly salaries of those in the room (we could base it on this meeting cost calculator)? Perhaps the IT wallahs could also come up with a way of monitoring the number of people who are not actually in the room in any useful sense, because they are on email/twitter/Facebook/doing their online shopping?

And in case you think I’m picking unfairly on academics, corporate, NGO and thinktank conferences are all usually awful, in their different ways (thanks Tolstoy)

Rant over, reactions please, including top tips for how to organize good conferences on negligible time/money. See some previous cathartic post-conference posts on epistemic communities and an even more prolonged purgatory in Delhi.

May 30, 2016

Thomas Piketty on inequality in developing countries (great, but still not enough on politics)

I heard econ rock star Thomas Piketty speak for the first time last week – hugely enjoyable. The occasion was the  annual conference of the LSE’s new International Inequalities Institute, with Piketty headlining. He was brilliant: original and funny, riffing off traditional France v Britain tensions, and reeling off memorable one liners: ‘meritocracy is a myth invented by winners’; ‘It’s difficult to be an honest country in today’s world. Britain used to be an honest country.’

annual conference of the LSE’s new International Inequalities Institute, with Piketty headlining. He was brilliant: original and funny, riffing off traditional France v Britain tensions, and reeling off memorable one liners: ‘meritocracy is a myth invented by winners’; ‘It’s difficult to be an honest country in today’s world. Britain used to be an honest country.’

He started with a mea culpa for the lack of attention in his best selling Capital in the 21st Century to inequality in developing countries. The good news is that he is now putting that right, with research under way on inequality in South Africa, Brazil, the Middle East, India and China. He gave us a preview on the first three.

His overall conclusion? ‘Official measures vastly underestimate inequality’. The most common reason for this is that inequality stats are drawn from household surveys, but samples of households typically miss the few megarich ones, and so underestimate the money at the top. He prefers to use tax and income data, which he has now got access to from governments because of his newfound fame. Even that data doesn’t tell the whole story, as it misses tax evasion, for example, but it’s a step in the right direction.

South Africa is notorious both for its income and wealth inequality and the failure of the post-apartheid governments to reverse it (despite progress in other areas, such as health and education). But what was more disturbing was Piketty’s findings on Brazil, where using tax data rather than surveys not only shows that the top 1% gets a much  larger share of national income than we thought, but reverses the trend from falling to rising (see graph). Ouch. Given how much attention has been paid to Brazil’s progress on inequality over the last 15 years, that is a pretty explosive finding. Questions raised include, is this true of other indicators (Gini, Palma)? Is the pattern repeated in the rest of Latin America’s supposed success stores? What does this mean for the World Bank’s claim that gini inequality is falling in a ‘small majority’ of developing countries? (here, p40)

larger share of national income than we thought, but reverses the trend from falling to rising (see graph). Ouch. Given how much attention has been paid to Brazil’s progress on inequality over the last 15 years, that is a pretty explosive finding. Questions raised include, is this true of other indicators (Gini, Palma)? Is the pattern repeated in the rest of Latin America’s supposed success stores? What does this mean for the World Bank’s claim that gini inequality is falling in a ‘small majority’ of developing countries? (here, p40)

Murray Leibbrandt of the University of Cape Town fleshed out the horror story on South Africa. The only ventile (5% band) to have increased its slice of income since 1993 is the top 5% – even the 5% below that has been hollowed out. Intra-racial inequality has risen within every ethnic group. Improved access to education has had zero effect on occupational mobility between generations – kids now go to school but still end up in the same jobs/earning similar amounts to their parents.

Piketty and Leibbrandt both acknowledged the importance of politics in all this (Piketty: ‘Political determinants of inequality are more important than pure economic determinants’) but they never dug into what this meant – it was back to stats, graphs and lists of good policies. So I jumped in when it got to Q&A and asked one of the big questions which I think arises from Piketty’s book. If world wars were responsible for the big redistribution episodes of the 20th C, and it is no longer possible to have (and survive) such wars, what political mechanisms could plausibly replace them?

Piketty’s response was a little unconvincing: Elites in developing countries can learn from developed ones; new social

Coming to an emerging economy near you

movements in poor countries can lead the way.

I think we can do better than that. We need to divert a bit of all the scholarly attention devoted to number crunching and policy wonkery into understanding the politics and history of redistribution. I still haven’t given up hope of getting some research going on this – work by David Hudson and Niheer Dasandi (see one page summary here) suggests that over 20 countries have had prolonged (> 8 years) periods of redistribution in the last half century. We need to understand the politics of why those episodes began (country case studies and identify common patterns). That could help us identify and support countries that could embark on similar trajectories today. Anyone want to fund/run the research project? The alternative is a combination of reverting to a handful of iconic (and highly Western) cases we do know about (US New Deal, UK welfare state) and bleating on about political will. Not good enough.

May 29, 2016

Links I Liked

The grim power of data: heat map of migrant deaths and cemeteries in the Mediterranean since 2014 [h/t Max  Galka]

Galka]

The IMF (or at least its more thoughtful parts) continues to startle old lags like me used to denouncing it as irredeemably ‘neoliberal’. The latest issue of its flagship magazine, Finance and Development, includes a glowing profile of Dani Rodrik (uber critic of the Washington Consensus) and a piece asking if neoliberalism has been oversold (to which it answers, partly yes).

I work a day a week at the LSE as Professor in Practice, along with Owen Barder, Kevin Watkins and Laura Kelly, so it’s understandable that Angelina Jolie should seek some of our reflected glamour by becoming the latest LSE PiP……… It prompted plenty of snark, but also interesting discussions on celebs and academia, e.g. here and here. [h/t Alice Evans]

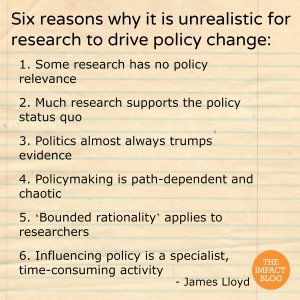

Staying with academia, Six reasons why it is unrealistic to expect research to drive policy change got people v steamed up

Staying with academia, Six reasons why it is unrealistic to expect research to drive policy change got people v steamed up

Good backgrounder on Brazil’s political crisis

14 top books on African politics (broadly defined) – looks like a useful list

Brilliant. Drone footage of climate smart agriculture in Bangladesh, from Practical Action

Both mesmerizing and scary – approaching the planetary boundaries and fast. Given tipping points, it’s like watching as we approach the cliff edge and just keep going.

May 26, 2016

Bridging the gender data gap – Oxfam is looking for a researcher. Interested?

Oxfam’s research team is looking for a gender justice researcher. Closing date is Monday (30th May), so despite  having only one typing hand (bike accident, not nice), Deborah Hardoon explains why you should apply

having only one typing hand (bike accident, not nice), Deborah Hardoon explains why you should apply

In 1990 Amartya Sen wrote an editorial for the NY Times review of books that highlighted a numerical discrepancy with profound implications. He looked at data on birth rates – all over the world there are around 105 or 106 male children for every 100 female children. This is just the biology of reproduction. After birth, given the same amount of care and nutrition, girls do better than boys – we are hardier, better at resisting disease and live longer. As a result in Europe, Japan and the US, there are about 105 women for every 100 men. However in parts of Asia and North Africa, women do not fair so well. In China there were just 94 women for every 100 men and in the Indian state of Punjab, just 86 women. Sen calculated that the difference between the gender ratios in countries where men and women generally receive equal treatment and the ratio in parts of South Asia, West Asia, and North Africa. More than 100 million women are “missing.” The cause was a combination of selective abortion and neglect.

‘These numbers tell us, quietly, a terrible story of inequality and neglect leading to the excess mortality of women’ he concluded.

Sen’s path-breaking work exemplifies the value of gathering and analysing data that is both disaggregated by gender and that measures what really matters. We have plenty of evidence of discrimination and the abuse of women’s rights. From graphic examples of gender based violence and rape to economic and political exclusion and everyday sexism experienced by women and girls. This sort of evidence and the associated stories of the people affected paint a picture of a world in which women continue to face injustice on many levels. Beyond brining these injustices to life, we also know that quantifying issues is incredibly useful – for spotting trends and associated causes/effects, but also for communicating the scale and depth of issues using stark statistics. By revealing and naming, scrutiny and action become possible.

We live in a world today where data, Big and small, can tell us everything from how much a government spends on each department to the next book we are going to read. So it is incredibly frustrating that despite the fact that we recognise that there is a gender pay gap and very few women make it to the top, at the national level we still don’t really know what the income differences are between men and women, nor how much decision-making power men and women have over how their household income is spent nor if trends are getting better/worse. This is because income and asset ownership is generally measured at the household (not individual) level. Bad data and tenuous extrapolations can be unhelpful and undermining, some gender related stats have been particularly contentious.

We live in a world today where data, Big and small, can tell us everything from how much a government spends on each department to the next book we are going to read. So it is incredibly frustrating that despite the fact that we recognise that there is a gender pay gap and very few women make it to the top, at the national level we still don’t really know what the income differences are between men and women, nor how much decision-making power men and women have over how their household income is spent nor if trends are getting better/worse. This is because income and asset ownership is generally measured at the household (not individual) level. Bad data and tenuous extrapolations can be unhelpful and undermining, some gender related stats have been particularly contentious.

Which is why there is a huge need for better data, as recognised by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation’s new commitment to spend $80 million to plug the gender data gap. But data alone isn’t enough. We also need great researchers and analysts to dig into the data we have, inform the development of new indicators and methodologies to measure what matters and communicate that widely, particularly making the data come alive, demonstrating what it really means for women and girls.

That is why we are currently recruiting for such a person. We are looking for a skilled researcher who is great with numbers and looking to apply this to issues of gender justice. This will involve exploring how to measure and analyse empowerment and exploring women’s rights issues, particularly from a quantitative perspective, in both our programme work on the ground and campaigns on Rights in Crisis, Inequality and Climate Justice. If this sounds like you, please apply by May 30th.

May 25, 2016

Book Review, Augusta Dwyer: The Anatomy of Giving (on the aid industry and Haiti)

If you want a readable and short (167 pages) introduction to the many contradictions and debates that beset the aid business, I recommend The Anatomy of Giving (apologies for Amazon link – couldn’t find another). Dwyer’s subject is Haiti – ‘At just a two-hour flight from Miami, Haiti is the Western Hemisphere’s own little piece of Sub-Saharan Africa.’ She’s been visiting on and off since 1985 and, inevitably, a lot of the book discusses the chaotic and widely condemned response to the 2010 earthquake.

aid business, I recommend The Anatomy of Giving (apologies for Amazon link – couldn’t find another). Dwyer’s subject is Haiti – ‘At just a two-hour flight from Miami, Haiti is the Western Hemisphere’s own little piece of Sub-Saharan Africa.’ She’s been visiting on and off since 1985 and, inevitably, a lot of the book discusses the chaotic and widely condemned response to the 2010 earthquake.

What’s great about the book is that Dwyer is a progressive writer and journalist, not part of the aid business. She also writes really well – I first came across her when I edited her 1994 book On the Line, about life on the US-Mexican border, and her style has if anything improved since then. A nice mix of genuine curiosity about the real, messy lives and motives of people living in poverty, interwoven with sharp, often critical, analysis of the workings of the aid industry.

Here’s a sample:

‘Happy endings are what we look for when we try to help, positive conclusions to the negative, some kind of balance. Touched by true stories of suffering and hardship, we seek signs of progress when we give, some kind of movement in the battle against poverty and against the very fact that places like Cité Soleil exist in the 21st century. What the people who live in those places get, however, is far less clear and straightforward.’

Chapters work through the many facets of that industry: humanitarian response, long term development, support for export processing zones, voluntourism, celebs and philanthropists, the workings of the World Bank and other big institutions.

Overall, she finds little to recommend official aid – the chaos of the earthquake response, the penchant for panaceas, like ‘miracle trees’ or playpumps, the problems of ‘pathological altruism’ that does more harm than good.

But this is not a standard aid polemic: she largely avoids the straw men and has an eye for nuance, constantly reverting to the lives of real people to ground her analysis in what matters. In places it reads like an extended trip report, written in the first person, grappling with the confusion of conflicting versions of events as she tries to get to the bottom of what is really going on (always a lot harder than you expect). ‘Did I envy the T-shirt people their certainty? I had to admit that I did, actually. It must be nice to come to Haiti feeling enthusiastic and positive, instead of questioning everything.’

We’re here to save someone

Her overall standpoint is that grassroots empowerment is the way to go – the book sings the praises of social movements in Haiti, traditional structures of social solidarity and bottom up approaches that build on the strengths of poor communities, rather than laments their frailties (asset-based community development, positive deviance). In contrast the aid business is beset by arrogance, paternalism and self interest.

Throughout the book she wrestles with the dilemma of all aid critics – does she want it reformed or scrapped? In the end, she ends up with a kind of Gramscian ‘pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will’, arguing that if the aid business can find ways to help (and not harm) the kinds of grassroots initiatives she identifies and applauds, then it can recover its moral and political mojo:

‘As my flight circles above the denuded mountains of Haiti before zooming over the bright blue Caribbean, I realize that I am, after all, feeling optimistic about the potential for transformation of foreign aid and our attitudes towards giving. Maybe I shouldn’t be. But I feel that over the past few years I have been travelling towards a reaffirmation of the human spirit, from a sense of despair at all the mistakes we make, to a place of hope where we recognize that we are smart enough to change.’

May 24, 2016

So what do we really know about innovation in international development? Summary of new book (+ you get to vote)

Ben Ramalingam of IDS and Kirsten Bound of Nesta share insights from their new open-access book on

Ben Ramalingam of IDS and Kirsten Bound of Nesta share insights from their new open-access book on innovation for development (download it

here

). And you get to vote (see end)

innovation for development (download it

here

). And you get to vote (see end)

Innovation is increasingly popular in international development. The last ten years have seen new initiatives, funds, and pilots aplenty. While some of this involves genuinely novel and experimental approaches, we have also seen – perhaps inevitably – some re-branding, spin and posturing. This has led to a degree of justifiable backlash and cynicism – even the Financial Times weighed in, describing international development as having caught ‘an innovation fever’.

As one of us suggested last year, new movements for change tend to head in one of three directions: they become quickly discarded fads, they are institutionalised as unthreatening silos or – in a small minority of cases – they become genuine catalysts for transformative change.

The end of April saw the publication of our new open-access book, Innovation for International Development, published by Nesta. While Nesta has been building diverse partnerships, insights and knowledge about innovation in development in recent years, this is its first publication on innovation as it is undertaken, supported and facilitated by international development organisations.

We set out to capture, distil and synthesise diverse perspectives from the work of over 20 champions working at the  frontline of the innovation for international development movement: from bilateral donors to philanthropic foundations, from development banks to NGOs, from global alliances to social entrepreneurs. They reveal how individuals, organisations and networks have navigated the challenges of funding, organising, collaborating and scaling innovations.

frontline of the innovation for international development movement: from bilateral donors to philanthropic foundations, from development banks to NGOs, from global alliances to social entrepreneurs. They reveal how individuals, organisations and networks have navigated the challenges of funding, organising, collaborating and scaling innovations.

Four big picture messages stand out:

Show me the knowledge

Of course, patient and flexible sources of money help when it comes to trying out new ideas. But ideas, experiences and networks matter just as much – if not more. USAID’s Development Innovation Ventures has since 2013 provided technical assistance to help grantees think through growth strategies, cost projections and evaluation approaches. This has proved invaluable for initiatives such as MPOWER, which provides cheap, reliable off-grid electricity to low-income and rural individuals by allowing them to pre-pay for electricity via mobile banking. Support from Development Innovation Ventures helped MPOWER to demonstrate the economic viability and scalability of the approach, and reach more than one million households, each one saving on average $186 annually in energy costs.

Break the rules – with tact and diplomacy

Organising for innovation is as much about breaking the existing rules for how things get done as it is about doing new things. This means challenging ingrained assumptions and practices and simultaneously instituting new methods systematically for managing innovation better and anticipating future needs. Interestingly, many successful innovation in the sector are not even talked about as innovations. Some successful examples were framed as ‘transforming what we do’ or ‘achieving much better impact’ or ‘reaching many more people’. In doing this, many of the core principles of innovation – of searching, of testing, of iterating, of disseminating – do get applied. But it also seems – from the experience of Oxfam, UNICEF and others – that the principles are far more important than the language.

Collaborate openly, but carry a big negotiation stick

Collaborate openly, but carry a big negotiation stick

There is much talk in innovation about the importance of diversity– and this is no doubt vital for everything from generating new ideas, through to disseminating new approaches. But this diversity is not something that comes easily – genuine innovation requires careful brokering of common ground between very different actors and mindsets. Facilitation can take you some of the way, but you won’t be able to complete the journey without hard-nosed, hard-headed, negotiation of how to meet different and often competing interests. This is especially important given development donors’ growing focus on private sector partnerships. As IKEA Foundation’s work with the Better Shelter initiative highlights, to achieve sustainable innovation it is not enough to ignore the profit motive, or hope it can be navigated through principles of ‘corporate social responsibility’. Instead, hard questions need to be asked and answered: Who gains from innovation? By how much? In what ways? And with what development implications?

Don’t replicate solutions, change systems

Simply replicating novel practices is just one route to impact and scale, and can underpin very narrow, limiting, and singular views of innovation success. Achieving scale often means innovators have to broaden their focus from making the idea work to changing the wider system of which that idea is a part. Think about the motor car – it lagged behind horse-drawn carriages until there was a wider system of roads, traffic management, driving schools, legislation, and so on. This is arguably the case for all truly novel approaches. So innovators need to better see and understand whole systems, envision new models for how they might work, and work to navigate the power and politics of change. And of course all of this needs to happen in ways that give prominence to national and local ownership.

The GAVI case study is remarkable for its rapid expansion of vaccine coverage globally through better innovation, contributing to the immunization of an additional half a billion children since 2015 (yes, you read that right). But making this sustainable in the long term means GAVI has moved onto focus its innovation not just at the level of products (e.g. new vaccines) but also at the level of overall vaccine delivery and health systems. This means focusing on novel approaches for everything from strengthening national leadership to data and information systems and equipment and maintenance. This comprehensive approach underpins their refrain: ‘the system is the innovation’

Where next for innovation in development?

Given the breadth and depth of work that is under way, we feel reasonably confident in saying that innovation for  development is a movement that is here to stay, and is more than just a fad. But whether the movement will deliver against its promise – to be come a catalyst for change rather than a siloed activity – is still an open question.

development is a movement that is here to stay, and is more than just a fad. But whether the movement will deliver against its promise – to be come a catalyst for change rather than a siloed activity – is still an open question.

The one thing we are sure of is that transformative success will only happen if we make serious efforts to understand and learn about the ups and downs of innovation for development in an open, systematic and transparent fashion, and make sure the effort focuses on genuine development opportunities and needs. We hope that this book, and the contributions within it, provide a useful step in this direction.

And just because it’s ages since we had a poll, here’s your chance to vote:

Note: There is a poll embedded within this post, please visit the site to participate in this post's poll.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers