Duncan Green's Blog, page 145

April 10, 2016

Links I Liked

Refuge, 2016 version [h/t Laurie Adams]

Tax wonk Alex Cobham recommends this as his one thing to read on tax havens

We have a sexist data crisis. Ruth Levine and Mayra Buvinic on need to improve data on women and girls

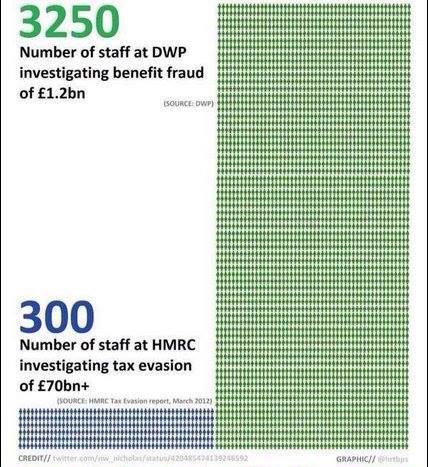

May have to start a new roundup of ‘infographics I enjoyed’, like this from Global Justice Now, on double standards in policing benefit fraud v tax evasion

May have to start a new roundup of ‘infographics I enjoyed’, like this from Global Justice Now, on double standards in policing benefit fraud v tax evasion

Oh good, another financial diaries research piece, this time on rural families – wish this methodology was used more (and not just on finance) [h/t Gawain Kripke]

How to persuade London tube travellers to stand on the left hand side of the escalator, not walk up it? Nice study in trying to change social norms.

of the escalator, not walk up it? Nice study in trying to change social norms.

Water Aid’s ‘State of World’s Water 2016′ is a model of brevity & comms punch. Read & learn.

Researchers & donors struggle to turn research into action. Answer is networks, not prize-winners says IDS’ James Georgalakis

Spent most of the week wracked by man flu, so I was delighted to see that this debilitating condition now has its own dedicated website, as well as this classic video explainer (for women of course; we guys already get it)

April 7, 2016

Blogging’s getting a bit old – what’s next? Plus, my first pitiful attempt at a vlog.

It’s quiet in the blogosphere. Too quiet. (In Westerns, saying that invariably means you’re about to get an arrow in

Caution: existential crisis imminent

the head). I’ve been blogging on FP2P for 8 years now and for the last few of them, have been wondering what comes next. There are few new entrants to the blog world, and some of the original development bloggers have fallen by the wayside (looking at you, Bill Easterly). Otherwise it’s a lot of the same old names chuntering away. That feels like a technology that’s ripe for disruption, so my question is – where do new arrivals go to write and exchange views, instead of starting a blog? Or as Jed Bartlett (still the best contender for US president, IMO) would say, what’s next?

I asked a few of my tech literate friends and colleagues and they came up with a few options:

Multipliers and Aggregators

One view is that blogging will not die, but will increasingly just be raw content – people won’t find their way to your website. Whether anyone reads your stuff will depend on how you feed it into an expanding superstructure of aggregators and multipliers, including:

Medium: Tech guru and MySociety founder Tom Steinberg has adopted it, which must mean something. Tom says it ‘has swallowed up a lot of the energy for Thinking Persons who want to write online. It feels like if you write there you get basically free readers and a higher chance of breaking out.’ Oxfam International is already there, and I may sign up. It seems to be more interactive and open access than sites like Huffpo – e.g. readers highlight their favourite quotes as well as like articles to move them up the pecking order.

Facebook Instant Articles. Up to now (confession) I have avoided Facebook, so don’t really know how this works, but I gather people are pushing content through instant articles and getting lots of hits – like Medium, that feels more like a multiplier than an alternative to blogging.

Facebook Instant Articles. Up to now (confession) I have avoided Facebook, so don’t really know how this works, but I gather people are pushing content through instant articles and getting lots of hits – like Medium, that feels more like a multiplier than an alternative to blogging.

Q&A formats

Blogging is really pretty top down – guy (usually) on a soap box, with people allowed to comment. More democratic, horizontal fora might be encourage more conversational exchange.

Quora.com: This from Oxfam tech guru Eddy Lambert: If you ever saw Yahoo answers etc. it’s a bit like that but way better and growing quickly. People ask questions (under categories and themes or to particular individuals/groups of experts) and other users respond. Discussions are the heart of it but also simpler ‘like’ voting for people to reward good answers or responses. Lots of algorithmic magic happens to then push ‘interesting’ content at you on-site, on-app and via email. Very vibrant communities form around themes or people. Why relevant?: because it rewards expertise and knowledge but everything starts with a question

Go retro – personal listservs

In a slightly back to the future vein, people are setting up personal email list serves to avoid all the adverts and just  talk to their mates – that seems like a bit of a backward step. Can people recommend any good development-related ones?

talk to their mates – that seems like a bit of a backward step. Can people recommend any good development-related ones?

Forget text, it’s all about video

Finally, what’s with the text obsession? I am reliably informed (i.e. by a journo friend in a pub) that text is dying, video is the future, provided it’s 90 seconds or less. Alice Evans at Cambridge is doing video abstracts for academic papers. Matt Andrews at Harvard has been doing video summaries of lectures for a while. The Guardian is getting loads of hits by just putting chunks of text on top of video footage. This is seriously bad news for old guys like me with the perfect face for radio. So if you don’t want to see the future, please look away now. My first vlog.

Think this should be my last one as well? I welcome all tips/suggestions to ensure FP2P doesn’t go the way of the fax machine…….

April 6, 2016

How do we make sure the Panama Papers lead to lasting reforms on tax evasion?

Scandals like the Panama Papers are a massive potential driver of policy change. In normal times, the sources of  inertia are great and politicians wishing to make change happen face an array of vested interests and fixed ideas telling them what they want is either insane or impossible. It takes a scandal to shake things up, delegitimize the status quo, and persuade decision makers that they really need new answers.

inertia are great and politicians wishing to make change happen face an array of vested interests and fixed ideas telling them what they want is either insane or impossible. It takes a scandal to shake things up, delegitimize the status quo, and persuade decision makers that they really need new answers.

But the political and media spotlight will move on. Some crises leave a legacy of change, in others, the waters merely close over the wreckage and life and politics go on as normal. So my exam question for you, dear readers, is ‘how can campaigning organizations ensure that in a couple of years’ time we will look back and be able to say that the current scandal triggered serious reform of tax havens?’

In the case of Oxfam, the timing couldn’t have been better: we launched a campaign on the evils of tax havens at the Davos meeting this year. We showed how they deprive poor countries of $170bn a year, exacerbate inequality etc. Our messages were perfect for this week’s hullabaloo: David Cameron needs to step up at next month’s anti-corruption summit, and do something about the role of Britain’s own Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies – places like the British Virgin Islands that have featured prominently in the Mossack Fonseca paper trail.

We got in early once the story broke, with an initial reaction on Sunday night followed up by a press release setting out ‘5 steps for Prime Minister to put UK’s house in order before tax and corruption summit’. That ensured we got our share of media coverage and were able to stress Britain’s role both in the problem and potential solution. That’s important because the danger is that the summit will present corruption as purely a developing country problem – that will be a lot harder now.

We got in early once the story broke, with an initial reaction on Sunday night followed up by a press release setting out ‘5 steps for Prime Minister to put UK’s house in order before tax and corruption summit’. That ensured we got our share of media coverage and were able to stress Britain’s role both in the problem and potential solution. That’s important because the danger is that the summit will present corruption as purely a developing country problem – that will be a lot harder now.

Fine, but what else? Apart from enjoying the adrenalin of the moment, what (if anything) can we do to strengthen the long term impact of the current scandal? I’d love to hear people’s thoughts on this. A couple of suggestions from me:

Voices of the Global South. We need to establish the idea that tax havens are a development issue – much as we worked for years to reframe climate change as being about people as well as polar bears. The $170bn number is useful, and much quoted, but it would help to have some real people saying the same thing. I’m not sure it’s credible to find someone to say ‘my kids can’t go to school because of tax havens’, but at least get some developing country finance ministers up there saying the same thing on a national level.

Those voices also need to be at the table on any negotiations, to ensure developing country interests are represented in any big overhaul of the system. Let’s hope we hear more on that at the IMF/World Bank Spring Meetings next week.

Commitments that provide real levers for future advocacy. Politicians saying ‘we must do something’ can all too easily turn into not very much. A commitment to change the law, the acceptance of a principle (e.g. ‘OTs and CDs should be subject to the same laws as the rest of us’) even to start a review process, is preferable.

New sources of money: The Robin Hood Tax could prove to be one of the big legacies of the 2008 crisis – 10 EU countries are currently introducing it (though not the UK, sadly), with potential big wins for climate change and aid funding. The fines on BP after Deepwater Horizon paved the way for some important change in the US Gulf states. What’s the equivalent here? Some kind of withholding tax, with a portion allocated to developing countries?

New Players: The Robin Hood Tax campaign pulled in unusual suspects such as faith organizations (the Salvation Army) and mainstream civil society players like the Women’s Institute. Widening the coalition around tax haven reform could have a lasting impact. Floods helped get insurance companies much more vocal on the economic risks of climate change – are any private sector allies coming out of the woodwork over Panama?.

Any other suggestions?

And in case you were on some other planet this week, here’s the two minute animated explanation of what this is all about

[And thanks to Nick Bryer, Luke Gibson, Oli Pearce, Max Lawson and Jon Slater for their suggestions]

April 5, 2016

Book Review: Gender at Work: Theory and Practice for 21st Century Organizations

Gender at Work: Theory and Practice for 21st Century Organizations by Rao, Sandler, Kelleher and Miller, Routledge,  2016

2016

This was another book that came to my rescue as I was struggling towards the finishing line on How Change Happens. In particular, it pulled together thinking about different kinds of power and change in a practical format for activists.

The book draws on 15 years of the ‘Gender at Work’ network of 30 gender and equality gurus and practitioners, with a cornucopia of case studies of attempts to promote gender equity in organizations from the global (UN Security Council, Amnesty) to the national (Moroccan Ministry of Finance) to the local (Dalit organizations in Uttar Pradesh).

Although the focus is on promoting change on gender rights within organizations, its uses go even wider.

The big idea is the ‘Gender at Work Analytical Framework’ for thinking about how change happens in any given context. It’s a standard 2×2 that locates change processes according to the nature of the institution in question (on a scale from informal to formal) and the locus of the change sought (ranging from individual to systemic).

The authors find that activists typically neglect the left hand side – the informal world. By reminding us to look at change in terms of all four quadrants, the framework stresses the need for work to happen at all levels (individual, community, formal politics, etc.) and it helps activists map who else is working on a given issue and identify gaps in the collective effort.

To use the framework, think about how the different aspects of the change process that you are considering fit into the different quadrants. Aspects of individuals’ access to resources, such as credit, or jobs, or health and education, belong in the top right quadrant; what is going on inside their heads – issues of awareness, confidence and ‘power within’, belong on the top left. At a systemic level, visible power exercised through laws and policies goes on the bottom right, but often, more informal institutions such as social norms play a significant role, and belong on the bottom left. Change processes will flow between the different quadrants, and activists’ attention should move from one to the another in response. The many facets of power (visible, hidden, invisible etc) permeate each quadrant, influencing how change happens.

To use the framework, think about how the different aspects of the change process that you are considering fit into the different quadrants. Aspects of individuals’ access to resources, such as credit, or jobs, or health and education, belong in the top right quadrant; what is going on inside their heads – issues of awareness, confidence and ‘power within’, belong on the top left. At a systemic level, visible power exercised through laws and policies goes on the bottom right, but often, more informal institutions such as social norms play a significant role, and belong on the bottom left. Change processes will flow between the different quadrants, and activists’ attention should move from one to the another in response. The many facets of power (visible, hidden, invisible etc) permeate each quadrant, influencing how change happens.

Separate chapters then delve into each quadrant in more detail, again with loads of meaty case studies to illustrate.

The framework is used for ‘assessment, strategy development and mapping outcomes’ – i.e. a regular way to revisit your work, think about whether and how the system has changed, and adapt your intervention in response. The authors’ other ‘key ideas’ include:

‘Accomplishments in one quadrant can be strategies for change in another. For example a gender policy (a lower

right achievement) can be leveraged to obtain more resources for women’s organizations (an upper-right accomplishment), which may be invested in training local women in advocacy techniques (an upper-left change).

right achievement) can be leveraged to obtain more resources for women’s organizations (an upper-right accomplishment), which may be invested in training local women in advocacy techniques (an upper-left change).Sooner or later a successful change effort must come to grips with the social norms and deep structure issues of the bottom left quadrant.’

Those deep structures and their ‘pervasive influence’ is one of the big messages of the book. Whether in advocacy or changing your own organization, any number of clever laws, policies and communiqués will count for little until they confront the underlying structures of power that continuously generate and regenerate inequalities within organization and in the world at large

In the final chapter, the authors wade into the current debates on results and theories of change.

‘One very popular theory of change is that gender equality can be achieved (or at least advanced) by well-designed, measurable interventions that accomplish goals in the short to medium term. Successes are scaled up and replicated.’

In response the authors call for a ‘more nuanced understanding of how change for gender equality happens. Many of the important changes (consciousness change and change of deep structures) are difficult to measure, happen in unexpected time frames and the outcomes are unpredictable.’

In response the authors call for a ‘more nuanced understanding of how change for gender equality happens. Many of the important changes (consciousness change and change of deep structures) are difficult to measure, happen in unexpected time frames and the outcomes are unpredictable.’

My only criticism is that the book if anything undersells itself – dull cover, high price (£29 paperback) and some fairly stodgy NGOspeak writing. But the ideas are great, and relevant way beyond work on gender rights work – I hope it gets the wide readership it deserves.

April 4, 2016

Some fascinating new research on how food prices affect people’s lives and politics

One of the projects I was proudest of getting off the ground while in (nominal) charge of Oxfam’s research team was ‘Life in a Time of Food Price Volatility’, a four year study of the impact of the chaotic food prices of recent years on the lives of poor people and communities in rural and urban communities in ten countries. DFID funded it (thanks!), and IDS were our main research partners. Ace Oxfam researcher Richard King worked his socks off managing the project, before going off to a well-earned rest at Chatham House. Now the project has published its findings in a special issue of the IDS Bulletin. And it’s free online, because unlike lots of other journals, IDS has taken the Academic Spring seriously and has gone full open access (but that’s a topic for another rant).

‘Life in a Time of Food Price Volatility’, a four year study of the impact of the chaotic food prices of recent years on the lives of poor people and communities in rural and urban communities in ten countries. DFID funded it (thanks!), and IDS were our main research partners. Ace Oxfam researcher Richard King worked his socks off managing the project, before going off to a well-earned rest at Chatham House. Now the project has published its findings in a special issue of the IDS Bulletin. And it’s free online, because unlike lots of other journals, IDS has taken the Academic Spring seriously and has gone full open access (but that’s a topic for another rant).

The research is fairly unique because we went back to the same communities year after year to see how the food price story unfolded, and combined this micro level research with macro number crunching to try and put together a more complete story than usual about how a global phenomenon like the food price spike of 2008 (and subsequent price volatility) fed through into poor people’s lives and then affected the wider society. In her article on the research methodology, Naomi Hossain (the brains behind a lot of it) captures this analytical framework in a diagram.

The conclusions of all this effort? This conclusion from the overall Introduction to the bulletin by Patta Scott-Villiers and Alexandra Wanjiku-Herbert:

‘The significance of the price shock comes through in every one of the country case studies. Millions of people have made decisions that though they may not be completely irreversible, are not being reversed. Life has changed. Homes have changed, women have found new roles, children have learned new ways of eating, families have re-oriented their centres of gravity. Our interlocutors in villages and urban areas showed how these shifts often came about quite suddenly. The costs of these changes can be seen in increased stress. The social fabric that people have relied on during previous cost-of living crises have started to unravel. Many stories tell of less solidarity between neighbours or even family members. The solidarity is still present, but it is less automatic than it might once have been. We saw more and more people turning towards the, as yet, unreliable, inadequate, badly timed and often corrupt, but less socially burdensome formal sources of welfare, because these come without expectations of reciprocity. In an age of price uncertainty and increasing demands on household income, many people feel that old style reciprocities are no longer suited to their lives.

Other stories tell of women having to fit in care duties after long hours of paid work outside the house, and cooking is getting quicker or even in some cases disappearing altogether. In many locations men are travelling further to work, only to find their jobs ever less secure; they are eating fast-food calories that often lack valuable micro-nutrients and they are increasingly eating apart from their families, changing the ways in which families interact.

Nutritional and poverty measures suggest that people have coped well, because the measures neglect the detail of  how coping and resilience is actually achieved and who is paying the price. There are all kinds of non-monetary effects on family, social or gender relations; there are psychological problems; people find themselves obliged to eat foods they fear. In development discourse, though concerns about micro-nutrients and non-communicable diseases have gained ground in recent years, the general perception is that we are making good progress because we can record increased income and increased calories. These achievements notwithstanding, if development means wellbeing, we are not making as much progress as we think. Calories and income are being bought at a cost of malnutrition, stress and attenuation of care. Of course, these shocks are also unlocking many kinds of beneficial opportunities as people react and look for new ways of making a living, educating their children and fulfilling their social and familial obligations.

how coping and resilience is actually achieved and who is paying the price. There are all kinds of non-monetary effects on family, social or gender relations; there are psychological problems; people find themselves obliged to eat foods they fear. In development discourse, though concerns about micro-nutrients and non-communicable diseases have gained ground in recent years, the general perception is that we are making good progress because we can record increased income and increased calories. These achievements notwithstanding, if development means wellbeing, we are not making as much progress as we think. Calories and income are being bought at a cost of malnutrition, stress and attenuation of care. Of course, these shocks are also unlocking many kinds of beneficial opportunities as people react and look for new ways of making a living, educating their children and fulfilling their social and familial obligations.

The first price spikes were almost a decade ago in 2008. Recent stabilisation of prices may indicate that the situation is under control. But it seems that government social policy may be lagging a decade or so behind the reality for people under stress. Stabilising prices, while welcome, is neither assured, nor is it going to be enough to provide development opportunities to those who have already been forced to change their way of life, for whom high prices remain a crucial barrier to improvements to life and for whom cultural change has swept away much that they once could rely on. It is time to start thinking not only about stabilising the price of food, but also making it possible for citizens to have greater control over what and how they eat, alongside rights to care, equitable gender relations and a fair working environment.’

The Bulletin includes thematic articles on food prices, and lots of fascinating case studies with titles like ‘The Role of Fatalism in Resilience to Food Price Volatility in Bangladesh‘. I whole heartedly recommend the bulletin to anyone working on food or nutrition.

April 3, 2016

Links I Liked

Lots of tips on presenting your precious research findings in just 15 minutes to a bored conference

Why are white people expats when the rest of us are immigrants? This great polemic by Mawuna Remarque Koutonin is the most visited Guardian Development post for ages, they tell me

‘It was scaled, it was sustainable. And it didn’t work.’ Smart 6m Matt Andrews video on scale v adaptation in trying to reform institutions

New OECD paper finds that the expansion of the finance sector has led to lower growth, and higher inequality. Suggests reforms

Governance guru Sue Unsworth died last week. Suvojit Chattopadhyay had a nice summary of her contribution to rethinking aid and institutional reform

China’s engagement in African agriculture is not what it seems. Excellent summary of the findings of a big IDS research project

Against Activism (we need Organizers instead). But ‘social justice warrior’ is even worse. Smart essay [h/t Louise Williams]

Revolution in the Academy: Superb 30 minute BBC documentary on student movement to overhaul how economics is taught in UK universities and beyond. And proof of why we need the BBC. [h/t Max Lawson]

59 years on, this is still the best April Fools prank ever (we Brits didn’t know about spaghetti in those days)

and I quite liked the Economist’s April Fool for wonks – Does eating ice cream make you smarter? A nice correlation v causation in-joke. Recommendations include ‘year-round subsidised ice-cream for children could improve educational attainment. And ice-cream vans should park closer to libraries to help boost reading skills too.’

March 31, 2016

What can historical success teach us about tackling sanitation and hygiene?

Ooh good, another ‘lessons of history’ research piece. Check out the excellent new WaterAid report: Achieving total  sanitation and hygiene coverage within a generation – lessons from East Asia.

sanitation and hygiene coverage within a generation – lessons from East Asia.

The paper summarizes the findings of four country case studies: Singapore, South Korea, Malaysia and Thailand, all of which produced ‘rapid and remarkable results in delivering total sanitation coverage in their formative stages as nation states’. I can certainly vouch for Singapore – I spent 3 years there as a child in the late 60s. Whenever the rains came, the main roads flooded, turning the city into an insanitary swamp. Not any longer.

The paper concludes: ‘Although their initial conditions were very different from those currently found in ‘fragile’ and ‘least-developed’ countries in Africa and South Asia, some useful conclusions can be used to inform discussions on development of strategic approaches to delivering sanitation for all:

The paper concludes: ‘Although their initial conditions were very different from those currently found in ‘fragile’ and ‘least-developed’ countries in Africa and South Asia, some useful conclusions can be used to inform discussions on development of strategic approaches to delivering sanitation for all:

High-level political leadership was crucial and did not stem from community-driven demand.

That leadership did not restrict itself to high-level exhortation, but was marked by an ongoing engagement in the implementation agenda.

Some element of subsidy was included, but alongside demand creation, and was often indirect (e.g. through housing subsidy).

‘Course correction’ mechanisms were devised at all levels so that obstacles to implementation were quickly identified and addressed with remedial policy reforms.

Hygiene, cleanliness and public health aims drove sanitation improvements.

A well-coordinated multi-sector approach was a necessary condition for rapid sanitation improvements.

Capacity building happened alongside sanitation improvements.

The vision of total sanitation coverage came before attainment of levels of national wealth.

Reaching a threshold of per capita GDP was not decisive in the strategic choice to set the course to deliver total sanitation coverage.

Monitoring was continuous and standards raised as goals were achieved.’

I would underline a couple of things emerging from the summary: firstly, stuff that you might expect to be important,

Sanitation v GDP

but wasn’t – leaders did good things to build the nation, even though there was no bottom-up pressure. Activists who routinely say nothing happens without pressure from below please take note.

Second, lot of elements of systems thinking/how change happens here: course corrections, multi-sector approaches, ratchet mechanisms to continuously raise goals as progress was achieved.

Third that they didn’t have to wait to get rich – you can start long before then.

But there’s a big question that the report doesn’t answer (and in that it resembles many other attempts to raid history for policy ideas): what were the politics that allowed this to happen? Here we have dirigiste one party states in Singapore and Malaysia, and military governments in the early years of take-offs in South Korea and Thailand. It’s no good just focussing on their policies while ignoring the politics – would such policies have been possible with more inclusive, democratic governments and if so, how? Need to get onto the democratic developmental state discussion if this is to be genuinely useful.

So while I applaud the attempt to oxygenate today’s policy debates with a sense of what has worked in the past, ignoring the power and politics discussion in here seems to paint a very partial picture.

My collection of useful ‘developmental lessons of history’ work now comprises

Trade and Industrial Policy (Ha-Joon Chang, Alice Amsden, Robert Wade and co.)

Agriculture (Ha-Joon again)

Education and Health (Santosh Mehrotra)

Popular Campaigns (Friends of the Earth)

To which I still intend to add something on the history of successful redistribution. Any other candidates?

March 30, 2016

Tackling Inequality is a game changer for business and private sector development (which is why most of them are ignoring it)

Oxfam’s private sector adviser Erinch Sahan is thinking through the implications of inequality for the businesses he interacts with

interacts with

Mention inequality to a business audience and one of two things happens. They recoil in discomfort, or reinterpret the term – as social sustainability or doing more business with people living in poverty. Same goes for the private sector development professionals in the aid community (e.g. the inclusive business crowd).

A good example is the UN Global Compact, which steers companies on how to implement the SDGs. They completely side-step the difficult implications of inequality on business and redefine the inequality SDG as boiling down to social sustainability or human rights / women’s empowerment goal. All good things that we at Oxfam also fight for, but these can all happen simultaneously with increasing concentration of income and wealth amongst the richest – i.e. rising inequalityWe know that rising inequality is one of the great threats to our society and economy. So why is business and the aid world so uncomfortable with tackling it head on?

Inequality is a relative rather than an absolute measure. This often makes it a zero-sum game – to spread wealth and income more equally, someone probably has to lose. But the intersection of business, sustainability and development has become locked into an exclusive focus on win-win approaches where there are no trade-offs and everyone gets their cake and eats it too. Addressing inequality often hits the bottom line – meaning changes to the prices paid to farmers, wages paid to workers, taxes paid to government and prices charged to consumers. But there is hope. Through a new lens (or metric) that should drive how business addresses inequality: share of value.

Now that’s what I call zero sum

Don’t confuse this with Creating Shared Value, which is focused on the win-win (without commenting on how the created value is shared). What I’m proposing is a measure that compares businesses on how they share value with workers, farmers and low-income consumers. In fact the concept dates back to the original principles underpinning the fair trade movement some decades ago.

Measuring how value is shared

Consider for instance that cocoa farmers used to get 16 per cent of the value of a chocolate bar in the 1980s. Today, they get less than 6%. Let’s measure this for all products and services in our economy to answer: what value goes to workers, farmers, governments? How is it changing? Which companies share more value with the stakeholders that need it?

Or the Kenyan Tea Development Agency – a business owned by 550,000 small-scale tea farmers with 66 tea processing factories, where farmers receive over 75 per cent of the final tea price. Meanwhile, tea farmers across the border in Rwanda, without a similar business model, only earn 25 per cent. These differences are at the heart of what inequality means to business.

Measuring how value is shared rubs up against the DNA of business. It takes discussions into the negotiation room, somewhere that development or sustainability practitioners are not welcome. Beyond what’s necessary to retain business partnerships, businesses aren’t wired to leave money on the table. I certainly never did in the various sectors I’ve done business in. But how can you share more value with the very people you’re also negotiating with (directly or indirectly)?

Going into the negotiation room

Mixing sustainability and pricing feels unnatural for business. Whenever I ask a company touting their sustainability credentials (often companies sourcing from developing countries) the question “do you know if the prices you pay allow for sustainable production”, I always get a hostile response. One ‘sustainability leader’ once responded on a panel I was moderating: “we are not a charity, why would we pay more for our commodities than we have to?”

Inequality is driven by business, and the robots will make it worse

The trend driving rising inequality is that value is increasingly being captured by capital rather than workers (see graph). The business world drives this trend as business-as-usual keeps squeezing value from workers. And it’s likely to get worse, with increasing mechanisation (see the alarming headlines below). I’m exploring this with one executive in a global tech company who is worried that their business model forces them to channel value to shareholders and thinks a restructuring of business may be needed if we are to avoid spiralling inequality and joblessness. Shouldn’t we promote businesses that defy this trend, before the robots take over?

If you’re doing business with people on low incomes (or affecting them in some way) – negotiating wages, negotiating farmgate prices, paying taxes, negotiating what you charge them for your product or service – then we need to scrutinise if you’re increasingly squeezing value away from them. In a nutshell, that’s how the inequality SDG relates to business.

If business is serious about the SDGs, and understands the potential dangers of rising inequality on the stability of our world, it needs to find a way to scrutinise whether it fights or fuels inequality. Measuring share of value would be a good start.

If business is serious about the SDGs, and understands the potential dangers of rising inequality on the stability of our world, it needs to find a way to scrutinise whether it fights or fuels inequality. Measuring share of value would be a good start.

March 29, 2016

Is Decentralization Good for Development?

My LSE colleague Jean-Paul Faguet has got a

book out on decentralization

. Here’s where he’s got to on the  narrative, following multiple launch events

narrative, following multiple launch events

I’ve just published a book by this name, and have spent a fair part of the last few months lecturing on it in various countries. Many people have asked me “So is decentralization good for development?” I thought I should answer:

YES.

A slightly more nuanced view

It’s always good to begin by defining key terms. Let’s define ‘development’ as increasing human well-being and freedom. What exactly do we mean by ‘decentralization’?

You might think that’s the easier question, but weirdly it isn’t. Not because ‘development’ is simple, but rather because there is far less agreement about what exactly decentralization means, and also less attention given to it. As a result, people employ it – often forcefully – in significantly different ways.

Misunderstandings of decentralization are both obvious and subtle. Let’s start with the obvious. Decentralization does not mean the abolition of central government. It does not mean the transfer of all functions to regional or local governments. For the most part, it does not even mean the complete transfer of any service to subnational governments.

Put so plainly, such a corrective sounds unnecessary. Who would argue that we don’t need central government? I’ve been working in this field for 20 years, and I don’t know anyone serious who promotes decentralization understood in any of these ways. But oddly, many of those who argue against decentralization focus their firepower on an enemy that, on closer inspection, looks surprisingly like a straw man.

Put so plainly, such a corrective sounds unnecessary. Who would argue that we don’t need central government? I’ve been working in this field for 20 years, and I don’t know anyone serious who promotes decentralization understood in any of these ways. But oddly, many of those who argue against decentralization focus their firepower on an enemy that, on closer inspection, looks surprisingly like a straw man.

So let me say it clearly. With the exception of some very local services with few or no economies of scale, like rubbish collection, the center will continue to be involved in local service provision, even after radical decentralization, in important ways.

What decentralization does, rather, is to empower (or create) subnational governments by devolving significant resources and authority to them. It makes the provision of local, regional, and national public services the joint responsibility of two or more levels of government. It transforms a simple, linear system of bureaucratic fiat (think command and control), run from the capital, into a much more complex system of coordination, cost sharing, and overlapping responsibilities amongst multiple tiers of autonomous government with independent mandates.

The downside of increasing complexity is greater cost. But the upsides are potentially far more important. One is the greater robustness of a multi-tiered system of independent nodes to failure in any one of its parts. Imagine you live in a centralized country, a hurricane is coming, and the government is inept. To whom can you turn? No one – you’re sunk. In a decentralized country, ineptitude in regional government implies nothing about the ability of local government. And even if both regional and local governments are inept, central government is independently constituted, probably run by a different party, and may be able to help. Indeed, the very fact of multiple government levels in a democracy generates a competitive dynamic in which candidates and parties use the far greater number of platforms to outdo each other by showing competence, and project themselves hierarchically upwards. In a centralized system, by contrast, there is only really one – very big – prize, and not much of a training ground on which to prepare.

Macro vs. Micro-Information

Another key advantage is the greater, more detailed information that decentralized government should be able to

A Bolivian municipality

bring to bear on any public problem, no matter how small. To better understand this, consider the types of information required to solve any public problem, or provide any high-quality public service. One kind, of course, is technical expertise. Planning a vaccination campaign, designing an irrigation system, and building a water treatment plant are nontrivially complex problems. I could not do any of these things competently myself, and my guess, dear reader, is neither could you. They require specialized knowledge that relatively few people have. Such people tend to cluster in cities, not towns or villages. They tend to work for central government, where the pay is better and the challenges more interesting. Accordingly, central government has an important advantage in the different sorts of technical expertise required for effective service provision.

But service provision also requires what Elinor Ostrom called “time-and-place information”, meaning location-specific geographic, social, and economic characteristics pertinent to both the underlying problem and potential solutions. Such micro-information must be incorporated into service provision if services are to be both efficient and effective. When and where can the targets of a vaccination drive best be reached? Which local organization might be capable of managing an irrigation scheme? How are local sewerage needs likely to grow and change in the future? Information of this sort is crucial to the success of a public project. But it does not reside with central government, which has weak incentives to acquire it. It resides naturally with local government, which has much stronger incentives to find it out and act on it.

Another Bolivian municipality

The genius of a properly designed decentralization system is that it combines technical expertise from above with local time-and-place information from below, in a way that is superior to what either level of government could achieve on its own. This flows naturally from central and local officials’ independent incentives, operating through their parties and career aspirations. The result is greater public-sector efficiency, effectiveness, and faster development. Here’s my literature review on the impact of decentralization on healthcare and education, if you still aren’t convinced.

Information and public sector robustness have a strong implications for some of the broadest, most important the problems facing developing countries today, such as political instability, macroeconomic instability, secessionist movements and the threat of civil war, elite capture and clientelism. The book discusses decentralization’s effects on each of these issues in great detail. The panel will no doubt thrash many of them out this Wednesday.

Do you really believe in democracy?

Lastly, the question of democracy. These days, most people pledge allegiance to it. So consider this: Who should decide on local services that mainly affect the residents of a particular locality? Elected officials in that place, or elected officials in the capital? Officials elected by the affected residents, or officials elected by the entire nation?

I have heard colleagues declare their allegiance to both democracy and the centralized state, and I just don’t get it. Citizens must be allowed to vote… but only for national government? They must not be allowed local governments? Local services with few externalities – like local policing or primary education – whose effects are overwhelmingly concentrated on the residents of a locality… must be provided by a distant central government? Someday maybe someone will succeed in explaining this view to me. But for now – after 20 years of studying and thinking about it – it seems arbitrary, incoherent, and wrong. You either believe in democracy or you don’t. If you really do, and if locally-specific services exist, then you must believe in local democracy too. And here’s a general paper and my paper on Bolivia if you want to dig further on the democracy question.

March 28, 2016

Links I Liked

Where does the world’s food grow? Good overview + maps from Brookings Institution

What’s the latest economic research on Africa? David Evans with another monster instant bibliography (plus links) of the papers presented at the recent African Economics conference

‘Boaty McBoatface’ wins online book’s title as well as cover…..

The battle for women’s land rights in India pits progressive law against oppressive culture

Rolling the development dice. Lovely lyrical reflection on progress, luck and his father’s life by IDS’ Ben Ramalingam

The case for stealth innovation (dont take your new idea to the boss until it’s up and running). Harvard Business Review advice rings a bit too true

What can the aid biz learn from IT project management? Pete Vowles on agile delivery v doing development differently

Wow. Nixon adviser John Ehrlichman on the motives for starting the war on drugs: ‘the Nixon White House had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities’.

The Obamas tango in Argentina. Now imagine the Trumps in their place……

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers