Duncan Green's Blog, page 146

March 24, 2016

What did trade campaigns achieve? Plus reinventing Robert Chambers & changing aid narratives: some Berlin conversations

Had a really interesting couple of days in Berlin last week, at the invitation of the German government aid agency, GIZ. Also spent time with the impressive policy and campaigns wonks at Oxfam Germany. Here’s a few of the topics that came up.

What did all that trade campaigning achieve?

From the late 90s to 2005, when I was working on economic policy for CAFOD, I watched Oxfam investing massively

Seattle 1999, a lot of fun, but what did we achieve?

in trade campaigns at the WTO and beyond. What did it achieve? We have a few impressions, but it would be great to go back, 10 years on, and do something more rigorous. Over Earl Grey in a cafe with an Oxfam colleague, we came up with:

Shifting broad narratives, eg spreading the idea that the trade system is riddled with ‘rigged rules and double standards‘ that benefit the strong at the expense of the weak – things like investor-state disputes that give big corporations huge influence over governments, or the use of agricultural subsidies to protect Europe and North American agribusiness, and deprive developing country agriculture of potential markets.

Preventing harm: eg helping developing countries defeat the EU’s attempts to shoehorn new issues (investment, competition policy) onto the agenda of the Doha Round in order to prise open new markets for their investors, and distract attention from their agriculture policies.

Defending flexibility on policy space for developing countries on issues such as Access to Medicines/generics or patent systems on seeds (UPOV) or, more generally, special and differential treatment for developing countries

But otherwise the campaigns achieved very little positive change in what was a largely defensive exercise. And the danger is that now the campaigners have moved on to climate change, tax, or whatever, the forces of darkness will reassemble and carry on out of sight – the devil not only has the best tunes, he also has a lot more stamina.

How on earth would you go about testing any of this? Nice job for the new Oxfam influencing impact researcher, once we find her/him.

A lot of the How Change Happens pitch is basically a call for aid agencies to listen to Robert Chambers. Robert didn’t win the battle first time around – why should this time be different?

time to listen to Robert?

Robert’s great work on participatory approaches, for example Rural Development: Putting the Last First (1983) did have considerable impact on how people understand development, but could not prevent the aid world’s slide into linear thinking, logframes, best practice etc. Some differences this time:

There is a weaker left, but also a weaker right, so more chance of a meeting in the middle. Robert was tapping into a larger, more organized current of progressive politics and ideas, but at a time when the broader political and economic tides were extremely hostile (Thatcher, Reagan, Friedman etc).

This time around the debate is less polarized. Large parts of the aid establishment are ready to acknowledge the failure of many traditional approaches. And in some ways, a lot of the thinking I have been reflecting on this blog is not actually that threatening/progressive – there are currents within the ‘Doing Development Differently’ work that clearly put effectiveness before social justice or redistribution. At worst, they can be about those in power getting better at imposing top-down institutional reforms that see civil society as the obstacle, and the people as passive beneficiaries, not part of the solution.

So I would say there is more chance of finding common ground, but maybe the politics of that new synthesis won’t be that radical.

How has the broad narrative of aid changed? What is missing?

Reflecting on the current diversion of aid towards spending on refugees and counter-terrorism, one comment was ‘aid used to be about them, now it’s about us’. I think it’s more complicated than that

It started off being mainly about us – eg the Cold War and the use of aid to support allies

Causes of death, global,

For about 10 years from the end of Communism to 9/11, it became more about them

Since then it has become more about us, in the sense of using aid to deal with threats to the West

But there has also been increasing attention to a ‚bigger us‘ in the shape of collective action problems/global public bads (climate change, tropical diseases)

What still hasn’t happened enough is:

Attention to common (rather than collective) problems, like tobacco, alcohol, mental illness, obesity, road traffic. All of these do far more damage than more typical ‘development issues’ like malaria, yet barely register on the radar as ‘development issues‘.

Learning from them – when do you ever hear of innovation in the South being adopted in the North? A few signs – mobile banking in East Africa, or the way campaigners on domestic violence in Canada adapted a methodology that originally came from Uganda, via South Asia. Any others?

Thanks to everyone in Berlin who took the time to chat – more please!

March 23, 2016

Payment by Results hasn’t produced much in the way of results, but aid donors are doing it anyway. Why?

I recently attended (yet another) seminar on the future of aid, where we were all sworn to secrecy to allow everyone

Simples. Or is it?

(academics, officials etc) to bare their bosoms with confidence. So I can’t quote anyone (even unattributed – this was ‘Chatham House plus’).

But that’s OK, because I want to talk about Payment by Results, which was the subject for my 10 minutes of fame.

When reading up I was struck by the contrast between how quickly PbR has spread through the aid world and how little evidence there is that it actually works. In a way, this is unavoidable with a new idea – you make the case for it based on theory, then you implement, then you test and improve/abandon. In this case the theory, ably argued by CGD and others, was that PbR aligns incentives in developing country governments with development outcomes, and encourages innovation, since it does not specify how to, for example, reduce maternal mortality, merely rewards governments when they achieve it.

Centre for Social Justice, October 2012

Those arguments have certainly persuaded a bunch of donors. The UK government website says that this ‘new form of financing that makes payments contingent on the independent verification of results is a cross government reform priority’. DFID called its 2014 PbR strategy ‘sharpening incentives to perform’ and promised to make it ‘a major part of the way DFID works in future’. British Prime Minister David Cameron waxes lyrical on the topic (left).

Which made the prevailing scepticism of much of my reading all the more striking – see for example Paul Clist and Stefan Dercon: 12 Principles for PbR in International Development, or BOND, Payment by Results: What it Means for UK NGOs, or 3 studies by NORAD (the Norwegian aid agency) .

Clist and Dercon‘s principles set out a series of situations in which PbR is either unsuitable or likely to backfire. For example if results cannot be unambiguously measured, lawyers are going to have a field day when a donor tries to refuse payment by arguing they haven’t been achieved. They also make the point that PbR makes no sense if the recipient government already wants to achieve a certain goal – then you should just give them the money up front and let them get on with it. There’s also an interesting sleight of hand in the argument, as the kind of incentive argument that might work for individuals is applied to institutions, even though it is not at all obvious how eventual PbR payments to governments will translate into improved performance by individual officials.

NORAD points out that if PbR is to be used when you are trying to persuade a government into doing something it

But what if it’s a department that gets the bonus, not an individual?

doesn’t want to do, we already know how unlikely that is to succeed from the whole aid conditionality experience.

BOND finds that PbR contracts with NGOs are plagued by micromanagement and often amount to little more than transferring risk from donor to recipient (no results, no dosh).

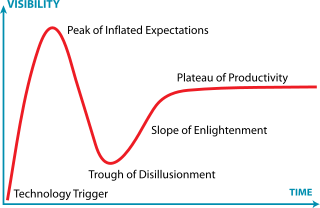

Even its originators, CGD seemed pretty underwhelmed at that earlier discussion on PbR, so why has it got such momentum among donors?

The PbR hype cycle seems to follow a well-established pattern in the aid biz, which I call the ‘microfinance syndrome’ (policy entrepreneur comes up with whizzy new idea → massive overselling to donors → disillusion when it fails to produce predicted miraculous results → reduced to niche product as we learn when the new snake-oil might actually be worth applying). At best, it’s a painful, inefficient way to innovate and improve the impact on poor people’s lives. Why not try positive deviance or venture capitalist style multiple parallel experiments instead?

Then what exactly are these results and who are we measuring them for? PbR pushes project implementation even further towards ‘upwards accountability’- mainly developing country governments collecting and processing results (which can be an expensive business) in order to satisfy aid donors and their political backers and tax payers. To what extent are those results any use for a) learning and improving or b) increasing accountability where it is really lacking – downwards to poor people and communities? My fear is that this will merely create a parallel system of results alongside the kinds of information practitioners need to learn and improve, diverting effort and money and doing nothing for downwards accountability.

Time horizons are a real problem: If (a big if) you could solve the problem of attribution becoming more attenuated with time, a 30 year PbR contract might indeed encourage innovation, certainly far more than a 3 year one, where there is too little time to experiment and take risks and find a better path to results. In fact, short-term PbR contracts appear to discourage innovation – there isn’t time to learn by failing, so stick with the tried and tested, even if it’s not that good. But there is precious little appetite for longer project cycles – political and management timelines seem to be shortening instead.

Time horizons are a real problem: If (a big if) you could solve the problem of attribution becoming more attenuated with time, a 30 year PbR contract might indeed encourage innovation, certainly far more than a 3 year one, where there is too little time to experiment and take risks and find a better path to results. In fact, short-term PbR contracts appear to discourage innovation – there isn’t time to learn by failing, so stick with the tried and tested, even if it’s not that good. But there is precious little appetite for longer project cycles – political and management timelines seem to be shortening instead.

Trawling through the interwebs for this piece it looks like a lot of the PbR discussion comes from the health sector – could this be another problematic attempt to import medical thinking into development, like randomized control trials?

Anyway, even though the evidence seems pretty thin that introducing PbR achieves improved results (ironic, eh?), donors are jumping into PbR contracts with gusto. Why is that? Conspiracy theorists/political economists please form an orderly queue.

March 22, 2016

If you think knowledge is expensive, try ignorance. Smart new job in Oxfam’s research team

Oxfam’s new head or research Irene Guijt debuts on FP2P to urge you to come and work with her.

‘How Change Happens’ is a pretty popular topic of late on this blog, in case you hadn’t noticed. And not without reason. In a sector that invests $140 billion per year to reduce poverty and injustices, it is not just useful to know whether our bets on what might work or not are based on plausible theories of change; it is essential. Hence the proliferating studies, trials, meta-studies and the like – all seeking definitive answers to what works or not. Important insights are emerging on micro-credit, cash transfers, education and of course deworming. (Insights, it has to be said, not without controversy (see ‘worm wars’). Oxfam’s most impressive foray into all this has been its effectiveness reviews, which are making some important progress in finding ways to be both rigorous and relatively cheap ($20k a pop – a fraction of the cost of a big randomized control trial).

Influencing theory of change, type A

That’s all fine for programmes on the ground, but what do we really know about what works when it comes to the secret plans and clever tricks of influencing strategies, advocacy efforts and campaigns for local, national or global change? Not enough by a long stretch. And yet entire organisations assume that long-term influencing initiatives are the way to go when it comes to structural poverty reduction and transforming entrenched injustices. After decades of service delivery, many international NGOs in particular are approaching structural change by investing more in influencing strategies. But foundations too are shifting their attention – and resources in this direction.

Oxfam for one has given ‘influencing’ the thumbs up (but still only around 15% of overall spend), as a critical route for shifting the social norms, policies and practices that keep people poor and maintain entrenched injustices. Its global ambition is to become a Worldwide Influencing Network. This means the Oxfam confederation will focus its work on “influencing authorities and the powerful, and less on delivering the services for which duty-bearers are responsible”.

So we’ll see more use of power and gender analysis, more long term national influencing plans, and more tools to track their effectiveness. We should see more work that pushes for policy and practice shifts and closer alliances with movements and transnational networks. Oxfam will invest more in digital strategies and in working in emerging centres of power, as well as with ‘non-traditional targets’. Not quite sure yet what that means (I’m new here), but in my book that should involve a range of ‘unusual suspects’ including private sector, faith organizations, traditional authorities, scholars and other tiers of government.

All of this will need a strong grounding in what Oxfam already knows is effective when it comes to influencing – and

Type B

making the most of what others have discovered. So we are hiring a senior researcher to lead on this topic.

We’re looking for a passionate, curious and experienced researcher – someone equally at home in theories of political and social change and hands-on evaluation of influencing. We need you to provide state of the art technical advice on monitoring, evaluation and learning in influencing initiatives.

What we’re offering is:

A team of stellar, fun-loving fellow researchers that care deeply about research for impact and committed campaigners

A global confederation hungry to do more and better on influencing to tackle injustice

An amazingly diverse range of topics around which influencing efforts are taking place, including humanitarian crises, women’s empowerment, water governance, the role of the private sector, global climate change negotiations, and national tax haven eradication.

Type C: complicated but might actually work

An opportunity to contribute directly to outstanding thought leadership on influencing strategies and how to assess their effectiveness, making first class advocacy and public campaigning the foundation of Oxfam’s work.

You could even get to write the odd guest post for Duncan (if you don’t mind dealing with that kind of editor).

Applications are open until April 4. https://jobs.oxfam.org.uk/vacancy/senior-researcher-on-influencing-and-its-effectiveness–cap0194/3849/description/

March 21, 2016

Links I Liked

Europe according to Vladimir Putin [h/t Amazing Maps]

The top 10 sources of data for international development research. Handy users guide

The Bridge to Sodom and Gomorrah. Wonderful long read on life and struggle in an Accra slum [h/t Alex Evans]

How to deal with protestors. There’s President Obama, and then (sigh) there’s Donald Trump

Why do so many World Bank investments underwrite oligarchs? Hard hitting piece on the International Finance Corporation

Why do so many World Bank investments underwrite oligarchs? Hard hitting piece on the International Finance Corporation

In percentage terms, Arab states have shown the most improvement in women’s representation in parliaments. Surprised? [h/t Erik Soheim]

USAID is funding vultures equipped with GoPro cameras to identify illegal rubbish dumps in Peru, then sticking the results on social media to raise public awareness about the environment. Genius or bonkers? Definitely genius – watch this delightful video. [h/t Chris Blattman]

March 20, 2016

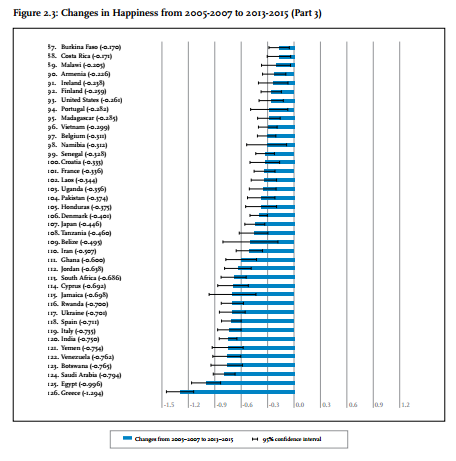

It’s international happiness day today, and there are some baffling national winners and losers

It’s international happiness day today, so what better way to ruin my Sunday morning than blogging about it? The World Happiness Report has a short update to mark the day. Happiness may sound a slightly woolly concept, but actually the report is based on rigorous assessments by Gallup of life satisfaction indicators (see here for more). Some highlights:

World Happiness Report has a short update to mark the day. Happiness may sound a slightly woolly concept, but actually the report is based on rigorous assessments by Gallup of life satisfaction indicators (see here for more). Some highlights:

Denmark wins (again) – how annoying is that? Enough to make any non-Dane grumpy.

Interesting focus on inequality in this year’s report:

‘The main innovation in the World Happiness Report Update 2016 is our focus on inequality. We have previously argued that happiness, as measured by life evaluations, provides a broader indicator of human welfare than do measures of income, poverty, health, education, and good government viewed separately. We now make a parallel suggestion for measuring and addressing inequality. Thus we argue that inequality of well-being provides a better measure of the distribution of welfare than is provided by income and wealth, which have thus far held centre stage when the levels and trends of inequality are being considered.

First we show that there is a wide variation among countries and regions in their inequality of well-being, and in the extent to which these inequalities changed from 2005-2011 to 2012-2015. In the world as a whole, in eight of the 10 global regions, and in more than half of the countries surveyed there was a significant increase in the inequality of happiness. By contrast, no global region, and fewer than one in 10 countries, showed significant reductions in happiness inequality over that period.

First we show that there is a wide variation among countries and regions in their inequality of well-being, and in the extent to which these inequalities changed from 2005-2011 to 2012-2015. In the world as a whole, in eight of the 10 global regions, and in more than half of the countries surveyed there was a significant increase in the inequality of happiness. By contrast, no global region, and fewer than one in 10 countries, showed significant reductions in happiness inequality over that period.

Second, the chapter shows that people do care about the happiness of others, and how it is distributed. Beyond the six factors already discussed, new research suggests that people are significantly happier living in societies where there is less inequality of happiness.’

The list of countries that have seen most improvement/deterioration in life satisfaction over the last decade begs an awful lot of questions – can anyone explain why Nicaragua, Sierra Leone, Ecuador, Moldova and Latvia are the fastest improvers?

The list of countries that have seen most improvement/deterioration in life satisfaction over the last decade begs an awful lot of questions – can anyone explain why Nicaragua, Sierra Leone, Ecuador, Moldova and Latvia are the fastest improvers?The countries with the most significant losses of wellbeing are more predictable, but even here there are some surprises. What are India, Botswana and Rwanda doing in the bottom dozen, alongside the more predictable Syria, Egypt, Yemen etc?

March 18, 2016

Does “Rational Ignorance” make working on transparency and accountability a waste of time?

Guest post from Paul O’Brien, Vice President for Policy and Campaigns, Oxfam America (gosh, they do have  august sounding job titles, don’t they?)

august sounding job titles, don’t they?)

As the poorest half of the planet sees that just 62 people have more wealth than all of them, collective frustration at extreme inequality is increasing. To rebalance power and wealth, many in our community are turning to transparency, accountability, participation and inclusion. Interrogate that “development consensus,” however, and opinions are fractured over the benefits and costs of transferring power from the haves to the have-nots.

In truth, our theories of change often diverge. Most development organizations may agree on the need to advocate for more Investment, Innovation, Information, strong Institutions and Incentives, but some organizations are genuinely committed to only one of those “I’s”, and that can be problematic: Oxfam often finds itself choosing and moving between the relentless positivity of politically benign theories of change (e.g. we just need more “investment”

Too much information

or “innovation”), the moderation of those who focus exclusively on transparent “information” with no clear pathway to ensure its political relevance, and the relentless negativity of activists that think the only way to transform “institutions” or realign the “incentives” of elites is to beat them up in public.

Oxfam’s challenge is to be both explicit in our theory of change, and show sophistication and dexterity in working across that spectrum. If Oxfam’s theory of change is based on a citizen-centered approach to tackling global systemic challenges like extreme inequality, then our opportunity may be engaging the “rational ignorance” of citizens and consumers.

Ignorance is rational when the costs of gaining knowledge outweigh the benefits. Rational ignorance is why I don’t read the Washington DC education budget even though my child goes to a public school here. It is why I never used to pick General Mills or Kellogg cereals based on their social justice performance. Until that answer was here and easy to find, my gut said it would take too much time, be irrelevant to my personal needs, would not give me a pathway to action, or when it did, wouldn’t be worth it. Even professionally, as more donors fund transparency work, there is just too much data and too many indices, to follow it all. In short, I would like to think my growing ignorance is mostly rational.

Rational ignorance is a profound threat to our theory of change. Oxfam recognizes that without systems for public accountability and active citizenry, states tend to forget their primary duty to regulate opportunity and power amongst their people. Instead power is captured. Oxfam’s relevance depends on our ability to overcome the rational ignorance of potentially active citizens. Our challenge is urgent—active citizenship cannot wait until states have capacity, elites get comfortable or political rights open up. Like Acemoglu and Robinson, we think public

Definitely too much information

institutions work best when political power is distributed at the same time as states build legitimate institutions.

That is why we celebrate when Ghanaian farmers march and present 20,000 signatures to successfully increase Ghana’s agriculture budget, or when consumers take more than 700,000 actions to get a slew of corporate reforms from the world’s biggest food manufacturers.

That doesn’t mean we are winning. As information channels grow, so does the rationality of ignorance, and our task is to make active citizenship more worthwhile. Peixoto and Fox’s findings are useful in this respect:

1) institutional responsiveness to citizen engagement tends to happen when online and off-line support are blended;

and 2) donor-driven transparency and citizen “voice” initiatives rarely yield institutional responsiveness. The ideas have to be owned by local institutions—either government or CSOs or both; and (3) exclusively demonizing the very elites from whom power must be distributed may not work.

Other lessons on overcoming rational ignorance:

(1) Translating data into relevance for citizens requires not just cutting-edge broadcast communication skills (see e.g. Tanzania) but interactive dialogue that allows citizens to shape debate, strategy and outcomes (see e.g. Burkina Faso).

(1) Translating data into relevance for citizens requires not just cutting-edge broadcast communication skills (see e.g. Tanzania) but interactive dialogue that allows citizens to shape debate, strategy and outcomes (see e.g. Burkina Faso).

(2) Timing matters. See how citizens increased engagement in Zambia and the Dominican Republic before elections.

Our field is awash with slick terms that re-describe but fail to resolve old challenges. “Rational ignorance” may be one such term. But if it signals that consumers and citizens will ignore transparency and accountability efforts unless and until those efforts meaningfully engage the personal self-interest or civic energy of the people we ultimately serve, then it is worth chewing on.

March 17, 2016

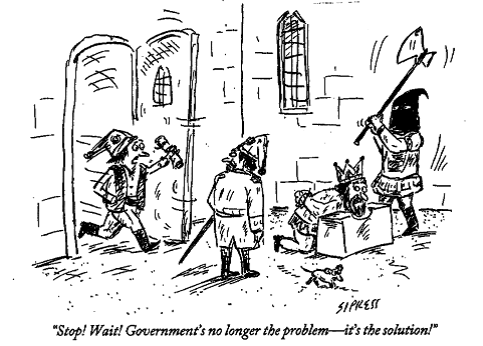

Industrial Policy meets Doing Development Differently: an evening at SOAS

It’s always interesting when a neglected issue suddenly resurfaces in multiple locations. That’s been happening with industrial policy – in particular the role of governments in developing their manufacturing industries. ActionAid has a new report out, arguing that promoting manufacturing through industrial policy is essential if countries want to generate decent work and tackling inequality.

It’s always interesting when a neglected issue suddenly resurfaces in multiple locations. That’s been happening with industrial policy – in particular the role of governments in developing their manufacturing industries. ActionAid has a new report out, arguing that promoting manufacturing through industrial policy is essential if countries want to generate decent work and tackling inequality.

Then I went to a packed SOAS event on ‘Smart Industrial Policy in the 21st Century’. The main speaker was my friend Ha-Joon Chang, who in April has a book by the same name published by the UN Economic Commission for Africa. This was billed as a ‘sneak preview’ (which usually means the publication has been delayed after the event was already booked in – I’ve been there…..).

Ha-Joon’s presentation was long and detailed, following the chapter structure of the book. He debunked the prevalent narratives on Africa (both the basket case and Africa rising variants) and got everyone laughing at the laziness of cultural stereotypes. Try this for a bit of Fabian racism. According to Beatrice Webb, writing in 1911, the Koreans were “12 millions of dirty, degraded, sullen, lazy and religionless savages who slouch about in dirty white garments of the most inept kind and who live in filthy mud huts”. No chance of that country coming to much, then.

He then went on to the theoretical arguments for (and against) industrial policy and argued strongly for the special place of manufacturing in development – it generates more, better jobs than agriculture or services, and even a knock-on effect on productivity in those sectors too.

He stressed that there is no blueprint – studying history encourages ‘policy imagination’ in contrast to the sterile stereotypes of ‘best practice’. Each country makes it up to some extent, notably Singapore, which defies any economic theory by successfully mashing up some of the most ‘free market’ measures (free trade, welcoming FDI) with some of the most ‘socialist’ ones (90% of land in public ownership, 22% of GDP produced by state-owned enterprises). Industrial policy needs to adapt to the new constraints created by WTO rules and global value chains by becoming more nuanced and intelligent, but Ha-Joon argued that it remains both feasible and if anything more essential than ever.

Then he got onto the political economy of all this, and where we can look for examples of success, at which point I perked up – for me this has always been the crunch issue. It’s all very well arguing, as Ha-Joon does, that other countries can learn about industrial policy from South Korea, Taiwan (and just about every developed country, including the US and Germany). But they had capable, independent state bureaucracies able to implement the ‘embedded autonomy’ required of developmental states (i.e. state bureaucrats were embedded enough in the market to understand what the private sector needed, but autonomous – not politically captured by vested interests looking for easy subsidies and state protection). What if you don’t have that kind of state? What if, as Alex de Waal describes, the rudimentary state in the Horn of Africa is actually disintegrating?

Then he got onto the political economy of all this, and where we can look for examples of success, at which point I perked up – for me this has always been the crunch issue. It’s all very well arguing, as Ha-Joon does, that other countries can learn about industrial policy from South Korea, Taiwan (and just about every developed country, including the US and Germany). But they had capable, independent state bureaucracies able to implement the ‘embedded autonomy’ required of developmental states (i.e. state bureaucrats were embedded enough in the market to understand what the private sector needed, but autonomous – not politically captured by vested interests looking for easy subsidies and state protection). What if you don’t have that kind of state? What if, as Alex de Waal describes, the rudimentary state in the Horn of Africa is actually disintegrating?

Ha-Joon pointed to places where such bureaucracies have been built along the way – the US and Prussia in the late 19th century or Latin America and East Asia in the mid-20th century. As anyone who has read his books will know, he has a fantastic grasp of history, and gave us the tour of the last four centuries of industrial policy. It was when he got onto the recent decades that alarm bells started to ring.

The book looks at experiences in middle income countries (China, Brazil etc) and in low income ones, with case studies from Vietnam, Uzbekistan, Ethiopia, and Rwanda. Ah. OK, so strong autocratic states can do this, but how about elsewhere? What advice for shambolic, patronage-based democracies, or crumbling states, where embedded autonomy and ‘getting to South Korea’ is really not an option? Anyone seen the ‘democratic developmental state’ recently? I’m not sure Ha-Joon (or anyone else) has an answer on this.

Mushtaq Khan was in the audience and addressed this point. He reckons that centralized industrial policy is pretty much impossible in such contexts – private sector rent-seekers will run rings round government, pocket the subsidies or protection, and deliver very little in the way of improved productivity.

What does seem to work, according to his case studies of the Indian auto and Bangladeshi garment industries in this  paper, seems to be a kind of ‘politically smart, locally led industrial policy’ for particular sectors, which provides incentives to the private sector only after they deliver (payment by results meets industrial policy? An interesting ideological confluence there). In India, the government created a joint venture with Suzuki, whereby the Japanese company galvanized a moribund auto sector with the incentive of access to India’s protected market. In Bangladesh, the multi-fibre arrangement guaranteed quotas for Bangladeshi exporters in key markets, so in 1979 the government persuaded the Korean company Daewoo to come in, set up factories and train up a new generation of Bangladeshi managers. They went on to set up their own factories and create a new industry.

paper, seems to be a kind of ‘politically smart, locally led industrial policy’ for particular sectors, which provides incentives to the private sector only after they deliver (payment by results meets industrial policy? An interesting ideological confluence there). In India, the government created a joint venture with Suzuki, whereby the Japanese company galvanized a moribund auto sector with the incentive of access to India’s protected market. In Bangladesh, the multi-fibre arrangement guaranteed quotas for Bangladeshi exporters in key markets, so in 1979 the government persuaded the Korean company Daewoo to come in, set up factories and train up a new generation of Bangladeshi managers. They went on to set up their own factories and create a new industry.

What’s nice about Mushtaq’s examples is that they avoid the twin extremes of ‘all you need is policy, just ignore the politics’ v ‘first build an effective state then worry about the industrial policy’. By working with the grain of particular sectors, weak and dodgy governments can still make some progress in boosting manufacturing and creating some kind of virtuous circle. But he has yet to find any examples in Africa, suggesting that even the South Asian experience may be too demanding in terms of administrative capability, autonomy and leadership.

More generally, it feels like this is crying out for an exchange between with the Doing Development Differently crowd of people working on governance and institutional reform – what would be the implications of hybrid institutions, PDIA, working with the grain etc etc for doing smart industrial policy in politically difficult settings?

Views?

Update: When I sent the draft of this post to Ha-Joon for comments, here’s what he said:

‘As for “can others ‘do a South Korea’?”, the first point is that South Korea was not ‘South Korea’ in the beginning. It became ‘South Korea’ because it started doing industrial policy and learned in the process and, more importantly, deliberately invested in building the necessary political and administrative capabilities.

The second point is that in the 1950s South Korea was considered a basket case. I don’t think anyone could have predicted that it will become a ‘South Korea’. Same story with Ethiopia. These countries became what they are because they wanted to be so. Here is where your points on leadership, coalition building, etc. come in.’

March 16, 2016

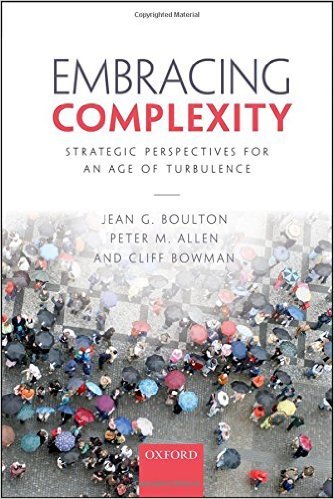

Which of these three books on complexity and development is right for you? Review/user’s guide

Dave Algoso (

@dalgoso

) with a handy guide to what to read for those wondering what all this complexity stuff is  about

about

In the last few years, complexity thinking has found its way into general development discourse. Anyone reading this blog or others has likely encountered some of the terminology, even if the technical pieces remain elusive to you. Ready to go deeper than the blogs? Time to read a book.

Fortunately, the last few years have also given the development sector three relevant books: Ben Ramalingam’s Aid on the Edge of Chaos; Jean Boulton, Peter Allen, and Cliff Bowman’s Embracing Complexity; and Danny Burns and Stuart Worsley’s Navigating Complexity in International Development.

It would take a committed development nerd to read the approximately 800 pages (not counting endnotes and indexes) of these three books. Since I am that nerd, let me help guide your reading.

First, the briefest possible explanation of complexity, for those who are new to the subject: Complexity thinking is a way of understanding how elements of systems interact and change over time, often leading to the emergence of unpredictable outcomes.

As a field, complexity lies somewhere between a philosophy and a science; Boulton et al call it a “worldview”. Don’t be misled by this hedging: complexity as a science (complete with computational tools and academic institutes) has found applications in ecology, meteorology, biology, physics, economics, and beyond. Yet there is great variety and even disagreement, so some find it more useful to talk about complexity sciences (plural). The popular intellectual landscape is also littered with concepts drawn from complexity thinking, such as tipping points, self-organization, power laws, adaptation, and wicked problems.

As a field, complexity lies somewhere between a philosophy and a science; Boulton et al call it a “worldview”. Don’t be misled by this hedging: complexity as a science (complete with computational tools and academic institutes) has found applications in ecology, meteorology, biology, physics, economics, and beyond. Yet there is great variety and even disagreement, so some find it more useful to talk about complexity sciences (plural). The popular intellectual landscape is also littered with concepts drawn from complexity thinking, such as tipping points, self-organization, power laws, adaptation, and wicked problems.

This all seems potentially relevant to the development sector. After all, what could be more complex than promoting development, sustainability, human rights, peace, and governance? Even in humanitarian aid, where the objectives may be more straightforward, the fragile contexts themselves are highly complex.

Each of these books tackles two questions—what complexity is and what it means for development/aid—in slightly different ways. Which you should read depends on what level of depth you want on either of those questions.

Embracing Complexity (Boulton et al) goes deepest on the technical aspects of complexity. The authors are complexity scientists themselves, expert users of the tools across disciplines and comfortable with terms like “equifinality” and “hysteresis”. However, their intended audience is non-specialists, and the result is authoritative yet easily followed.

As for aid and development, the book only devotes a single chapter (though other examples are scattered throughout the book). Boulton et al are actually writing about embracing complexity across many sectors. That said, the development chapter is worthwhile for its greater connection to the technical aspects of complexity described elsewhere in the book. In addition, separate chapters on the implications of complexity for management, strategy, and economics are highly relevant to development work.

Aid on the Edge of Chaos (Ramalingam) starts with a well articulated (if familiar) critique of the aid and  development sectors. That occupies a full third of the (360-page) book. The middle third then covers complexity thinking. Unlike Boulton et al, Ramalingam’s description of complexity is more conceptual and narrative. A reader leaves with a broad understanding of concepts like emergence and nonlinearity—certainly more than you get from blogs, but without exposure to the more fine-grained details that Boulton et al discuss.

development sectors. That occupies a full third of the (360-page) book. The middle third then covers complexity thinking. Unlike Boulton et al, Ramalingam’s description of complexity is more conceptual and narrative. A reader leaves with a broad understanding of concepts like emergence and nonlinearity—certainly more than you get from blogs, but without exposure to the more fine-grained details that Boulton et al discuss.

Ramalingam devotes the final third of the book to the implications of complexity for aid and development, covering adaptive strategies like positive deviance and PDIA, as well as analytical tools like social network analysis.

Navigating Complexity (Burns and Worsley) starts similarly to Ramalingam, with a critique of development and a review of complexity thinking, but both are much briefer. Burns/Worsley admit upfront that complexity theorists would find their treatment light while practitioners would find it heavy. In a single chapter, they cover just enough of the conceptual and technical side to then move readers on to the practical implications for development.

In particular, they cover three concrete approaches: participatory systemic inquiry, systemic action research, and nurtured emergent development. They tie each back to complexity concepts, with detailed case studies. Participatory approaches, learning, and network-building feature heavily.

Which should you read?

You’re busy (aren’t we all?), so let’s break it down in simpler terms. While each book is good and deserves a broad audience, each should find its key audiences based on its strengths:

Boulton et al’s Embracing Complexity provides the best detailed introduction to complexity, in both its thinking and practical applications. Key audiences: Strategists, managers, and anyone who wants to use complexity thinking in a detailed way.

Burns/Worsley’s Navigating Complexity is the most practical guide to complexity in development that I’ve seen. It also does a great job of putting participatory methods in a new light. Key audiences: Direct managers, designers, and evaluators of projects.

Ramalingam’s Aid on the Edge of Chaos gives the best insight into complexity’s implications for the sector at large. Key audiences: Donor staff, researchers, and think tankers.

This three-part review is hardly a summary of each book, but hopefully guides your further reading. Was this enough to whet your appetite, but you’re not yet sold? Duncan has previously reviewed both Embracing Complexity and Aid on the Edge.

This three-part review is hardly a summary of each book, but hopefully guides your further reading. Was this enough to whet your appetite, but you’re not yet sold? Duncan has previously reviewed both Embracing Complexity and Aid on the Edge.

Closing thoughts

All three books are selective in which aspects of complexity thinking they apply to aid and development: Boulton et al are selective because they spend relatively little time discussing development, Ramalingam and Burns/Worsley because they have not introduced the more technical components of complexity. But it leaves you with the sense that there may be a richer way to apply the tools and practices.

Relatedly, few of the development approaches described actually stem from the discipline of complexity thinking. Rather, the authors have worked backwards from various approaches to explain their success in terms of complexity. It suggests the possibility for developing entirely new practices with complexity applied more deliberately. To say updated on those, you’ll have to turn back to the blogs.

[Alternatively you could just cheat and read Oxfam’s handy intro to systems thinking in programmes]

March 15, 2016

Why everyone should have an RSS feed for daily news (and should help me replace the one I just deleted by accident)

Well that’ll teach me. I was just trying to write a post about my RSS feed and I’ve managed to delete the lot. No idea

Gone to that digital graveyard in the cloud…..

how. Can you help me reassemble/improve on my daily reading list?

The background: chatting to colleagues at Oxfam, I’m always surprised how few of them use RSS software (which apparently stands for ‘Real Simple Syndication’) to keep abreast of their fields. I use Feedly to create a personal online newspaper – every morning after checking the inbox, I trawl through about 60 headlines covering anything published in the previous 24 hours by my favourite gurus or websites. I probably click on about 10 of them, and then, if they’re any good, tweet the links. Then I move on to my twitter feed. Takes about an hour over coffee while my brain is struggling to wake up and means I start the day with a sense of what’s new in the world outside – I’d hate to start the day by diving straight into internal Oxfam stuff.

When I looked at the subscriptions list for the first time, I was surprised to find 74 (and that’s after deleting half a dozen that had stopped publishing). Then I deleted them all. Really annoying.

So here’s what I’ve reconstructed from memory and the screengrab I did before disaster struck – can you help with suggestions please? Only upside, you can’t be offended if your site isn’t here – I may just not have restored it yet!

And Aishah, this is all your fault…….

Funnies:

Overseas Development Institute

Oxfam: The Politics of Poverty

World Bank Let’s Talk Development

World Bank People, Deliberation, Spaces

Economists:

General Interest

So what am I missing? Is this how you use your RSS feed, or am I missing something?

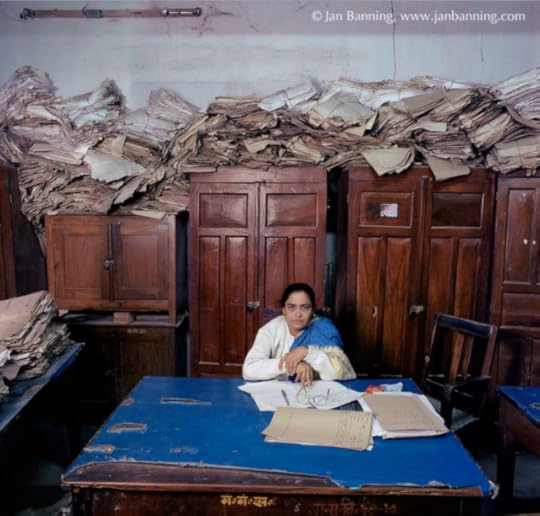

March 14, 2016

Links I Liked

Bureaucratics – great photo series of officials behind desks around the world. [h/t Chris Blattman]

Some wise advice from DFID reformer Pete Vowles for anyone pursuing change in large organizations

A top job in the Oxfam GB research team: Senior Researcher on Influencing and its Effectiveness (4 April deadline)

World Bank sets up nudge unit – the Global Insights Initiative (Gini). It will run experiments on nutrition, sanitation etc

Trump, Sanders and the backlash against globalization. Paul Krugman doesn’t see much point in defending further trade liberalization (diminishing policy returns, it seems)

Homi Kharas argues that 2015’s international agreements (SDGs, Paris, Addis) have a new theory of change, going beyond traditional inter-governmental deals to include markets, data and innovation.

Six lessons from trying to reach 10 million women in India with life-saving health information. Good ICT for Development piece

Ruth Levine asks why do experts in global development disagree so much about randomized controlled trials?

International Women’s Day miscellany

‘Today, I did 11 things that are illegal for women in other countries. What’s your score?’ [h/t Laurie Adams]

The ups and downs of gender gaps in happiness. Women are generally happier, except in poor countries, but there’s more to it than that.

The ups and downs of gender gaps in happiness. Women are generally happier, except in poor countries, but there’s more to it than that.

And my own small contribution. Once we get rid of all-male panels (Manels), the next challenge is dealing with tokenistic MAOWs (Men and One Woman) that seem to be replacing them

Love the sentiment, harmonies and moves on this Plan International IWD video from Uganda by my sister in law Mary Matheson. The girls wrote the lyrics, btw.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers