Duncan Green's Blog, page 150

December 10, 2015

Of MPs, chiefs and churches: Vanuatu’s parallel governance systems

This second installment of posts on my recent trip to

Vanuatu

covers the country’s dual (or even triple) systems of  governance.

governance.

Vanuatu’s parallel systems came into sharp relief when we left the capital, Port Vila, and headed for the village of Epau, passing the tree wreckage of Cyclone Pam en route. Conversations in the capital had all been about government, parliament and aid; in Epau, they all seemed very distant. Here, the chiefs are in charge, all nine of them – primary chief, assistant chief and the chiefs of the community’s four tribes.

According to a mixed meeting of chiefs, villagers and church leaders, the chiefs meet every Monday to decide what communal work is needed. They are decided by bloodline. When I ask what they do if a chief misbehaves, the villagers look nonplussed – ‘we’ve never had a problem, but I guess the village would meet to discuss the problem and work it out’. When money arrives from outside organizations, the chiefs ask for volunteers to manage it – they prefer not to do so themselves.

From the local to the national

When the cyclone hit, the chiefs called the community together and decided that the priority was to clear the road to allow in help, then start rebuilding the destroyed homes. The first outside help (the Red Cross) arrived a week later. In contrast, the villagers’ MP sent a single kilo of rice per household two months after the cyclone. He didn’t even come in person – just sent his representatives. The scorn is tangible. ‘Now we look down on him – we expected him to be the first here.’

In practice the formal, Western system of police, courts, government and parliament is tightly interwoven with the chief system – some observers don’t even think they can usefully be separated. When riots threatened to break out over the management of the Vanuatu National Provident Fund, the police sent for the local chiefs to calm people down. Moreover, the division of labour between formal and customary systems if constantly evolving. This from former Minister for Lands, Ralph Regenvanu:

‘These days, there are ‘traditional’ songs about mobile phones – it’s organic and fluid. There is an evolving division of labour: the chiefs have agreed that rape, murder, incest, and theft that is large scale or from foreigners should be dealt with by the police, partly because it is too divisive, and partly because they can no longer apply traditional sanctions (killing the perpetrators)’

In contrast, the management of land seems to be ever more in chiefly hands, not least because of Ralph’s role as Land Minister in pushing through legislation to strengthen the hand of the customary system. He believes ‘Chiefs are the ones genuinely trying to build community governance, more than Churches or civil society organizations. They are working tirelessly for no money, day in and day out. No-one wants to be a chief – you’re the unpaid chaser and fixer, it’s the ultimate voluntary job. Chiefs are a fantastic asset.’

Churches too are more present in many people’s lives than the formal state. One young professional wondered ‘why

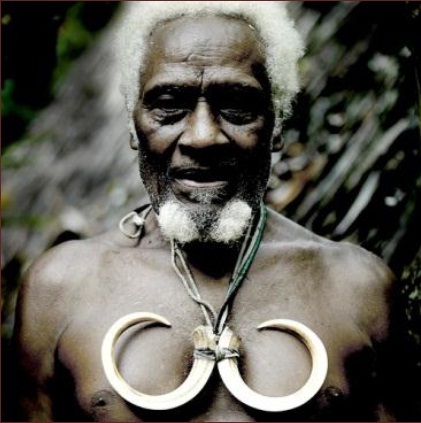

Traditional chief

is it that people obey the Church so easily and not the rule of law? You know where you are with the Church – it’s a code of belief, not just a threat of punishment’ (and quite a remote threat at that – people are more scared of divine punishment than human variety).

The chiefs v state division partly reflects a different world view – the chief system focuses on the collective, whereas the formal system, for example the legal process, privileges the rights of the individual. Customary law is often about making peace and reconciliation, rather than establishing guilt and redress.

That may sound good, but it is pretty disastrous when it comes to gender issues. According to Merilyn Tahi of the Vanuatu Women’s Center, domestic violence is widespread, but ‘compensation in reconciliation processes is often paid to the family rather than the women who have been abused. Formal systems are better at directly looking after victims. Yes we should make peace between communities, but women victims need [formal] courts.’

Nelly Willy, an exfamer who now runs the Pacific Leadership Program in Vanuatu, reckons ‘If we want good governance, we should go back to the chiefs – people are more connected to them than to their MPs. Yes there’s a lack of checks and balances, but it’s still better than the current system.’

According to one local academic I talked to, the clash between the chief system and imposed western models of governance also lies at the heart of Vanuatu’s corruption problem, because the modern system ‘criminalises social obligations’. Finding a way to reintegrate the two might be the best way to sort it out.

OK, so how might that work – could aid donors work much more closely with chiefs? The first challenge is a knowledge gap – there has been some work on the dual systems, e.g. Miranda Forsyth’s book, A Bird That Flies with Two Wings, but given how much it varies between islands, over time, and according to issue, an in-depth understanding of the customary system would be an essential starting point. That would allow donors and NGOs to think through change strategies, identifying, for example, the issues on which the chief system performs well/badly, the potential for building alliances and multi-stakeholder approaches with chiefs and others, the structures and incentives within the chief system, and how they could be influenced, and the critical junctures in chiefly life.

Modern chiefs: PM Sato Kilman and Chinese President Xi Jinping

But there is a fundamental problem here. A key aspect of the chief system is that it is organic – it varies according to time and place and is highly fluid. But the urge of outsiders is to codify and pin down. How to do that without killing the essence of the customary system?

Overall conclusion? Vanuatu’s system of chiefs and customary law is varied, pervasive and far more stable and legitimate (in terms of public acceptance) than the formal state system. But like any system, it is influenced by power and (increasingly) money. Donors and NGOs need to understand and work with the customary system, supporting ‘careful hybridity’ as Vanuatu changes, urbanizes and grows, but they also need to identify and address its weaknesses, notably on individual rights, especially of women.

If you want to read more about Vanuatu, I recommend this 2007 Drivers of Change paper, which is still very relevant

Why Paris must succeed – a brilliant video message from space

Heading into the final 24 hours (ahem…) of the Paris Climate Change negotiations, I wish the sleep deprived ministers and sherpas on whose decisions our collective fate rests could find 8 minutes to watch this brilliant message from the world’s astronauts

And here’s Alex Evans with a bit of background

December 9, 2015

China’s rise, Cyclone politics and extreme patronage: Impressions of Vanuatu

Pretty remote

As part of their support for the How Change Happens book, the Aussie government is also giving me a crash course in development in the Pacific. Last year, they took me to Papua New Guinea (blogs here), then last week, I headed for Vanuatu (small island archipelago, 270,000 population, best known – at least in the UK – for one island’s baffling reverence for Prince Phillip). Today I’ll share some overall impressions, then tomorrow I’ll explore the dual (or even triple) systems within which people live their lives – Chiefs, State and Churches.

Flying in, the first impression was the number of Chinese on my plane. Chinese influence is rising rapidly across the Pacific, with an influx of shopkeepers dominating the retail sector, while the government and large construction companies are pouring a lot of concrete – a huge convention centre now symbolically overshadows the Aussie high commission, being finished off by Chinese labourers in big hats behind the wire fences. I heard numerous complaints about unfair competition and lack of linkages to the local economy (the labourers reportedly even grew their own veg), although no-one was complaining about the low prices in Chinese-run shops. The general consensus seems to be that China doesn’t have a conscious strategy to take over the South Pacific. Most activity is commercial with no more specific aim than winning friends, but the ready availability of Chinese cash does make it harder for other donors to influence government policy.

On arrival in the capital, Port Vila, the half-sunken boats in the bay are a reminder of March’s devastating Cyclone  Pam – the worst Vanuatu has ever seen. The most striking thing was the success of disaster preparation and response – only 11 people died, according to government figures – all led by the government’s National Disaster Management Office. Unfortunately what happened next has left a lasting distrust between government and aid donors. While overall, NDMO with the backing of major aid donors, did a good job, it had to put up with an influx of disaster tourist NGOs, out of date or unsuitable food (Pepsi and Cocopops? Really?), predatory journalists ‘looking for bodies’ and insinuating themselves into the NDMO office where they were overheard using government wifi to haggle with news editors about the price for their photos. Ugh.

Pam – the worst Vanuatu has ever seen. The most striking thing was the success of disaster preparation and response – only 11 people died, according to government figures – all led by the government’s National Disaster Management Office. Unfortunately what happened next has left a lasting distrust between government and aid donors. While overall, NDMO with the backing of major aid donors, did a good job, it had to put up with an influx of disaster tourist NGOs, out of date or unsuitable food (Pepsi and Cocopops? Really?), predatory journalists ‘looking for bodies’ and insinuating themselves into the NDMO office where they were overheard using government wifi to haggle with news editors about the price for their photos. Ugh.

That is complicating the response to the current climate threat – El Niño. The rains haven’t come, and cyclone damage has affected water harvesting systems; in one village I was told ‘most of the crops have died, everything – the bananas and the cassava – has dried up’.

Returning to Port Vila from a field trip, we passed the local prison, where a man was busily painting the walls. Turns out he was one of the 14 MPs currently jailed on corruption charges – just the latest chapter in a story of extreme political instability, with votes of no confidence regularly triggering political crises and new governments (19 Prime Ministers in the last 24 years).

The anarchy springs from patronage politics with few constraints on MPs, who constantly swap parties (and governments) in search of political or financial advantage, and the effect on governance is devastating. One senior civil servant told me: ‘You have to be constantly thinking ‘right, who’s coming in next? How can I work them? You have to work on the dark side to get things done, drink with the pols to get them to sign the right documents, maybe agree to do a couple of stupid things to protect the integrity of the programme – we have even set aside a $100,000 fund for that kind of thing. But why can’t we just work together for our country? It’s too much of a headache – I’m thinking of going back to New Zealand (where he trained)’.

Patronage is particularly resilient because that’s what voters often want – they exchange their support for

mmm, that kava taste

direct benefits from the would-be MP. ‘People vote for school fee money, coffin money, wedding money. They vote with their stomach.’ Once in office, the MP then has to recoup that money, and more – corruption is endemic and massive. There are some good guys in the system, but until voter attitudes change, they will always be swimming against the tide.

Gender inequity is extreme – all 52 MPs are men, domestic violence is rife, out in the villages ‘bride price’ is seen as effectively confirming wives as the property of their husbands. Yet I met some inspiring women leaders, and change is coming through activism, led by a new generation of educated women in government and politics.

Needs garlic. And red wine sauce

That all sounds like a cocktail as bitter as the national drink, kava (which anaesthetises your facial muscles and makes you spit a lot – can’t say I took to it), but doesn’t really describe the feeling of the place. Much more welcoming and less violent than PNG, and once rated (according to the new economic foundation’s ‘Happy Planet Index’) the world’s happiest country. Go figure.

Oh, and flying fox is overrated, even in a red wine sauce. Like eating gamey meccano – thanks to Essi Lindstedt for the comparison.

Tomorrow, I’ll discuss Vanuatu’s fascinating parallel systems of governance – chiefs, churches and the state.

December 8, 2015

How assets + training can transform the lives of ultra-poor women: new evidence from Bangladesh

People are often very rude about ‘big push’ approaches to development – the idea that you can kickstart a country

Passport out of poverty?

(or a millennium village) by simultaneously shoving in piles of different projects, technical assistance and cash. The approach hasn’t got a great track record, but now a kind of micro Big Push, targeting the ‘ultra poor’ in a range of countries, is showing some really promising results.

The approach has been pioneered by Bangladeshi development organisation BRAC, which aims to help households escape extreme poverty by supporting women to set up their own small businesses. BRAC provides both assets and skills training for some of the poorest women in Bangladesh.

The women in the villages effectively choose between casual wage labour in agriculture or working as a domestic maid, and self-employment in livestock rearing. Before BRAC arrived, the poorest women were far more reliant on casual wage labour, while women from wealthier households were predominantly engaged in livestock.

This division matters. Hourly earnings for wage labour are on average about half those for livestock rearing, and livestock produces throughout the year, whereas demand for agricultural labour is seasonal. But the barriers to entry for livestock rearing are higher – i.e. you have to buy a goat or cow in the first place – meaning that the poorest don’t generally get to do this work.

So BRAC provided livestock worth about $140 per woman, and two years of training worth roughly the same amount.

Today the International Growth Centre, based at the LSE, is publishing the findings of a seven-year evaluation of the first of these programmes, covering over 1300 villages and tracking over 21,000 households over seven years, including 6,700 ultra-poor households and 15,100 from other wealth classes. The results are impressive:

Today the International Growth Centre, based at the LSE, is publishing the findings of a seven-year evaluation of the first of these programmes, covering over 1300 villages and tracking over 21,000 households over seven years, including 6,700 ultra-poor households and 15,100 from other wealth classes. The results are impressive:

Although the programme ended after two years, the benefits have continued to accrue: After four years, the ultra-poor increased hours devoted to livestock rearing by 361%, while hours devoted to maid services and agricultural labour fell by 36% and 17%, respectively. Working 22% more hours and 25% more days, earnings increase by 37%.

Benefits go beyond income: Four years after the initial transfer – and two years after direct programme support ended – the programme resulted in a 9% increase in per-capita ‘non-durable’ (i.e. food) consumption and a decline of 8.4 percentage points in the number of households living on less than $1.25 per day.

Household cash savings increased nearly ninefold, the value of household assets more than doubled and the household saving rate increased by 25 percentage points from an initial value of close to zero. The value of land owned by the ultra-poor rose by 220%, the value of productive assets tripled, and beneficiaries became more engaged in credit markets.

Overall, the programme seems to have triggered the kind of long term take-off that Big Push advocates everywhere

Identifying women who are ultra poor using PRA

dream of. The change in spending on non-durables was 2.5 times higher after seven years than after four, and the increase in land access doubled (see graph).

As for donors, the IGC team worked out that on average, for every £1 invested in the programme there was a return of £5.40 in terms of increased income and assets for the women concerned.

Two caveats spring to mind:

The report doesn’t discuss attitudes much, merely stating that poor women are poor because they are shut out of better jobs. Give them the assets and the training and they happily switch to better jobs. I wonder what happens when you take this approach into a more caste-ridden society such as large parts of neighbouring India, where barriers to social and economic mobility include attitudes both among poor women and their neighbours?

Is there no fallacy of composition at work here? Can everyone move from labour to raising livestock without messing up the markets for both?

I’m sure there will be lots of much techier people than me trying to find fault, but on the face of it, this looks like a truly impressive piece of research, and an even more impressive approach to ending extreme poverty. The approach has now spread to some 20 countries, and research in many of these suggests similar degrees of success. If the SDG commitment to ‘getting to zero’ is to mean anything, these kinds of programme are going to play a vital role.

BRAC founder Sir Fazle Hasan Abed will launch the report at LSE this evening, and the event will be livestreamed.

3m summary of the research findings here

December 7, 2015

Have those hard-won accountability reforms had any impact?

I hate gated journals, but

Kate Macdonald

(left) and

May Miller-Dawkins

(right) have kindly offered to

I hate gated journals, but

Kate Macdonald

(left) and

May Miller-Dawkins

(right) have kindly offered to  summarize the main points from some recent contributions to the

Global Policy Journal

on the impact (if any) of accountability reforms in aid

summarize the main points from some recent contributions to the

Global Policy Journal

on the impact (if any) of accountability reforms in aid

Many readers of this blog may have spent part of the 1990s and 2000s campaigning for increased transparency and accountability from the World Bank and other development banks. Under often intense external scrutiny and pressure a range of development finance institutions have since acknowledged the need to answer for their decisions to an expanding group of ‘stakeholders’ outside their organization, to promote adherence to their internal policies and in some cases to provide access to grievance procedures for those affected by their lending.

Was it worth the effort? Have relationships of accountability, which we understand as “moral or institutional relation[s] in which one agent (or group of agents) is accorded entitlements to question, direct, sanction or constrain the actions of another”, actually shifted? And if so, has it really made a difference to people’s lives?

Was it worth the effort? Have relationships of accountability, which we understand as “moral or institutional relation[s] in which one agent (or group of agents) is accorded entitlements to question, direct, sanction or constrain the actions of another”, actually shifted? And if so, has it really made a difference to people’s lives?

We pulled together a special collection of articles for The Global Policy Journal to explore these questions.

Lidia Cabral and Iara Leite on accountability in Brazilian development cooperation in Mozambique.

Samantha Balaton-Chrimes and Fiona Haines on the engagement of the World Bank International Finance Corporation’s independent accountability mechanism, the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman, in the Indonesian palm oil sector; and

Susan Park on the evolution of accountability mechanisms in the Asian Development Bank.

Here are some of the insights they generated:

Downwards accountability mechanisms oriented towards affected communities have been enthusiastically embraced by many lenders, but with mixed results

Accountability arrangements now look different, with more explicit commitments to strengthened accountability to  affected people.

affected people.

This is particularly true of the multilaterals. The studies on the ADB and the World Bank in Indonesia find that the new accountability mechanisms have indeed enhanced the capacity of communities to air their grievances. In some cases they have also enabled communities to access compensation for project impacts, such as loss of livelihoods, or to negotiate other improvements to their conditions.

However, the potential for these mechanisms to prevent or redress harm in the first place remains limited. The new accountability mechanisms can usually only ameliorate social or environmental harms resulting from a project, rather than stopping or fundamentally reconfiguring contested projects.

Multilateral accountability mechanisms are still influenced by the power and interests of powerful creditor governments, and governments of borrowing countries in which controversial development projects are located.

Notable differences are evident between the accountability practices of bilateral aid programs, and those of multilaterals like the World Bank or ADB, reflecting the differing political environments that each must navigate. Bilateral aid is dominated by accountability practices answering to domestic political constituencies on the use of public funds, and to recipient governments with regard to broader policy frameworks. They have often placed less emphasis on direct accountability to citizens of host countries affected by lending projects.

Notable differences are evident between the accountability practices of bilateral aid programs, and those of multilaterals like the World Bank or ADB, reflecting the differing political environments that each must navigate. Bilateral aid is dominated by accountability practices answering to domestic political constituencies on the use of public funds, and to recipient governments with regard to broader policy frameworks. They have often placed less emphasis on direct accountability to citizens of host countries affected by lending projects.

Local, national and cross border campaigning is an important driver of donor accountability. Particularly in cases where community grievances relate to whether or not a project goes ahead in the first place, or to more fundamental transformation of the terms of such projects, protest and opposition by people’s movements seems more effective than reliance on institutionalized accountability mechanisms that lenders themselves have established.

For example, a coalition linking protest movements in Mozambique with like-minded organisations in Brazil and other countries has fundamentally challenged the premises of a Brazilian-funded project in Mozambique, which many of them view as imposing a paradigm of large scale commercial agricultural development, threatening the livelihoods of both peasant farmers and the environment.

So has it all been worth it…?

New accountability systems can serve as useful political channels for marginalized social groups affected by Big Aid.  Downwards accountability practices have sometimes achieved modest but significant shifts in the norms and power relations underpinning decision making.

Downwards accountability practices have sometimes achieved modest but significant shifts in the norms and power relations underpinning decision making.

But while such institutional changes have benefited some project-affected people, they have failed to make a difference for many others. The unevenness of such impacts reflects the inescapable ways in which accountability institutions (like all institutions) remain constrained within broader relations of social power.

Whether we think all the hard won claims have been worth it perhaps depends on the level of ambition or modesty of our initial expectations. Learning from the successes and failures of the new accountability approaches is crucial, both to inform future campaigns or reform efforts, and to allow project-affected people and their allies and supporters to think critically about how they can best seek justice, remedy or change in the future.

December 6, 2015

Links I Liked (and last chance to comment on How Change Happens draft)

Been on the road, so here’s two weeks’ worth of top links. Plus final reminder: this Thursday (10th December) is the deadline for comments on the book draft – you know what to do.

The difference between US and UK, summed up in one 8 second video

Why is Einstein famous when no-one can understand relativity?

Cinderella Issues update:

Road safety is an equity issue. Low income countries have 1% of vehicles, but 16% of all road deaths

Big tobacco increasingly targets (& kills) the young in poor countries. Why are no big NGOs campaigning on the modern opium wars?

Big tobacco increasingly targets (& kills) the young in poor countries. Why are no big NGOs campaigning on the modern opium wars?

Professors v Jedi, left [h/t Shit Academics Say]

National MDG implementation: lessons for the SDG era. Better late than never!

Temporary versus permanent power shifting technologies (aka The Bomb v The Pill) by Tom Steinberg on his new blog

Causes of death in Shakespeare plays, below – delightful pie chart [h/t  @spookyjulie]

@spookyjulie]

Best things I’ve read on the Paris Climate Change negotiations:

How Copenhagen rebooted the theory of change behind international talks

Role of faith leaders in changing the debate

Saleemul Huq’s daily updates on the progress of the talks will be essential viewing as talks hot up when ministers arrive this week (here’s an example from last week)

Off topic, but it’s starting to feel Christmassy, so who cares? Adele, Jimmy Fallon & The Roots covering Hello with classroom instruments [v Chris Blattman]

December 3, 2015

‘Economics Rules’, Dani Rodrik’s love letter to his discipline

Dani Rodrik has always played an intriguing role in the endless skirmishes over the economics of development. His  has been a delicate balancing act, critiquing the excesses of market fundamentalism from the inside, while avoiding the more abrasive tone of out-and-out critics such as Joe Stiglitz or Ha-Joon Chang. He does sorrow; they prefer anger.

has been a delicate balancing act, critiquing the excesses of market fundamentalism from the inside, while avoiding the more abrasive tone of out-and-out critics such as Joe Stiglitz or Ha-Joon Chang. He does sorrow; they prefer anger.

His work has been hugely influential, helping to stem the tide of unthinking trade and finance liberalization, stressing the importance of institutions and national context, and developing (with Ricardo Hausmann) a methodology – growth diagnostics – which has been widely used not just to promote growth, but to identify and tackle bottlenecks and pinchpoints on many other issues, rather than try and reform everything at the same time.

His latest book, Economics Rules, continues in that tradition, a 200 page love letter to his beloved discipline, and a lament over how it has been misused. The problem, it seems, is always the economists, never economics itself.

The book focuses on what distinguishes economics – the use of models, which are ‘both economics’ strength and its Achilles’ heel’. Rodrik loves models, the more the better. Different issues or settings require different models to shed light on what is going on. Unfortunately, a combination of physics envy and arrogance has led some economists to insist on The Model (singular), putting ideology before pluralism often with disastrous results. The way economics is taught doesn’t help, with faculties promulgating the latest fads, and not equipping students to choose between models, according to context. It’s like medical schools churning out doctors who just prescribe the same pill for every disease.

Rodrik’s intended audience is twofold: first, the critics of economists – people like me who bang on about ‘the dismal science’ with only the vaguest idea of what economists actually do all day. He accepts a lot of the criticisms, but insists they are down to those bad economists, not the discipline itself, which is a paragon of pluralism and humility. Ahem. He points out that economists tend to circle the wagons when confronting Joe Public, putting aside their internal differences over issues like market failures in an effort to defend the fundamentals, especially the virtues of markets and the price mechanism, from barbarians who they think just don’t get it. I think he does achieve a degree of rehabilitation for his profession (only hope it appreciates him!)

His other audience is his fellow economists, and their successors. He urges them to beware False Gods – small insights are preferable to Grand Theories; maths is essential, but has to retain some connection with the real world. He moves at ease between the many econ tribes (the book is a handy introduction to the different schools of thought, by the way). Like a kindly uncle, he sees something of value in most of them.

His other audience is his fellow economists, and their successors. He urges them to beware False Gods – small insights are preferable to Grand Theories; maths is essential, but has to retain some connection with the real world. He moves at ease between the many econ tribes (the book is a handy introduction to the different schools of thought, by the way). Like a kindly uncle, he sees something of value in most of them.

I liked the book, I learned more about the discipline, and it made me think more kindly of Dani’s colleagues (heck, some of my best friends are economists….). But a few doubts surfaced too:

Rodrik’s world is still dominated by experts, judiciously choosing between models, advising governments and others. More aware of national difference, sure, but not much space here for bottom-up processes and solutions (unless those taking part have a PhD from a good university). Would have liked to see some discussion of when expert-driven processes are actually the wrong way to go.

In my experience, the really blinkered proponents of this or that model are not actually practicing economists, but those who studied it decades ago at University and are now in government or other sectors. In dividing the world up into professional economists and their critics, he misses out some crucial players and a big part of The Problem.

He really doesn’t like talking about power, politics or paradigm maintenance. The prolonged battles over

economic policy (in which he is a significant combatant) are presented as disinterested and civilized senior common room discussions. No-one is captured by vested interests. Everything is driven by evidence. I don’t believe that there is some monstrous conspiracy to turn all economics departments into battering rams for the interests of the rich, but it is at least worth noting that they often behave like that, and discussing more nuanced reasons why that might be so.

economic policy (in which he is a significant combatant) are presented as disinterested and civilized senior common room discussions. No-one is captured by vested interests. Everything is driven by evidence. I don’t believe that there is some monstrous conspiracy to turn all economics departments into battering rams for the interests of the rich, but it is at least worth noting that they often behave like that, and discussing more nuanced reasons why that might be so.Finally, I understand and admire his love of economics, but is it really credible to say that all the negatives are down to economists not understanding their own discipline; that there is nothing wrong with economics itself? Reminiscent of arguments about religious fundamentalism….. Isn’t there something inherent about the discipline that lends itself to arrogance and a blinkered approach to solving the world’s profoundly messy problems?

A lovely, insightful and highly readable book – go buy it (but not on Amazon).

December 2, 2015

Four Years On, The World Has Changed on Disability

Tim Wainwright, CEO of

ADD International

(& also chair of

BOND)

, finds much to celebrate today

Four years ago I wrote a blog, expressing my concern about how I felt that mainstream development was largely overlooking a large and highly excluded group: persons with disabilities. [Quick note on terminology: we use the term ‘persons with disabilities’ to reflect the UNCRPD terminology, but we recognise that disability rights movements worldwide also use ‘people with disabilities’ or ‘disabled people’]

Writing today, on the International Day of Persons with Disabilities, I think that the world has moved on. The question now is not if persons with disabilities should be included in development – but how.

A global promise

In the last four years we’ve seen an amazing shift. At global level, Agenda 2030 (aka the Sustainable Development Goals or Global Goals) includes 11 mentions of the inclusion of persons with disabilities within a wider commitment to ‘leave no-one behind’. When world leaders gathered in New York to adopt the Agenda, Barack Obama and the Pope both spoke about persons with disabilities. Disability is also included in the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, the Addis Ababa Action Agenda, and the latest draft of the World Bank’s social and environmental safeguarding mechanism. And here in the UK, DFID today marks the first anniversary of the publication of its Disability Framework with a refreshed version.

Photo by ADD International

It’s not just globally or in developed countries that things have been changing. In less than a decade the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) has been ratified in over 150 countries. Gradually, this has translated into positive changes in policy and practice even in very resource-poor contexts – for example in Tanzania, where ADD International is working with the local disability movement to help the government implement its new National Strategy on Inclusive Education.

How did this happen, you might ask?

Well, I think it had something to do with a relatively small group of organisations – members of the global disability movement and its allies such as ADD International – with a recent history of successful campaigning for the UNCRPD. These organisations came together again to campaign on the post-2015 agenda, and agreed on some very simple, sensible ‘asks’, backed up by evidence.

This mobilisation coincided with support from some key decision makers such as David Cameron on the Post-2015 High Level Panel, Macharia Kamau and Csaba Korosi on the SDG Open Working Group, and UN missions ranging from Australia to Brazil to Ecuador. Social mobilisation and political leadership were mutually reinforcing: it’s arguable that without the groundswell of activist and popular support for disability inclusion in the SDGs, it would have been hard for the decision makers to take the stand that they did. (A similar argument has been made on the role of feminist movements in changing norms on gender-based violence).

Crucially, the voices of persons with disabilities were front and centre to the campaign, and one of our key asks was that persons with disabilities from the South should be present in meetings. When invited, these excellent representatives made a case no-one could ignore.

And that’s why it meant such a lot that it wasn’t only the Pope and Barack Obama who spoke about disability at the

Photo by ADD International

Summit to adopt the SDGs, but also two representatives of the global disability movement and its allies – Vladimir Cuk from the International Disability Alliance, and my colleague Mosharraf Hossain. This would have been unthinkable when I wrote that first blog in 2011.

From commitment to action

Now, the question is turning to: ‘so how do we include persons with disabilities?’

Actually, it’s getting a bit more specific: ‘How do we do this in livelihoods, in education, in WASH (Water, Sanitation and Hygiene), in health, in transportation? How do we include women with disabilities, how do we work with older or younger disabled people, or with persons with disabilities living with HIV and AIDS? How do we ensure good evidence and disaggregated data?’

And a second, harder question follows: ‘How do we do this, to scale?’

Partnership and participation

I believe that the secret to tackling these twin challenges lies in partnership and participation.

Partnership is needed to support those organisations with good reach and sectoral knowledge to extend their services to fully include persons with disabilities.

Photo by ADD International

We at ADD have started to do this, both globally (for instance partnering with major think-tanks to look at economic inclusion through the lens of disability and gender) and locally (for example working with specialist justice NGOs to include women with disabilities in their programmes on gender-based violence).

Participation should be second nature to anyone in development. However, the phase ‘nothing about us without us’, a rallying call for the disability movement globally, is still one that needs repeating, sometimes quite loudly, in even the holiest of development shrines.

I am still shocked by how easy non-disabled people find it to have a meeting about disability and not notice that the people they are discussing are not represented, in the same way that people used to accept men-only boards and panels. I urge you to reflect on this next time you attend a meeting on the topic of exclusion – ask yourself who is not in the room, who is not invited to speak?

Looking at the future

Amazing changes have been taken place and it’s thanks to many people all across the development spectrum who have backed the inclusion of persons with disabilities in mainstream development.

Now, to tackle the challenge of how best to do this, we need to foster new partnerships, bringing together inclusion expertise with sectoral actors who can achieve scale, and we have to remember that only if persons with disabilities from the South are involved in a meaningful way from the very beginning will we ever stand a chance of leaving no-one behind.

December 1, 2015

You’re wrong Kate. Degrowth is a compelling word

Giorgos Kallis responds to

My friend Kate Raworth ‘cannot bring herself to use the word’ degrowth. Here are nine reasons why I use it.

1. Clear definition. ‘Degrowth’ is as clear as it gets. Definitely no less clear than ‘equality’; or ‘economic growth’ for that matter (is it growth of welfare or activity? monetised or all activity? if only monetised, why would we care?). Beyond a critique of the absurdity of perpetual growth, degrowth signifies a decrease of global carbon and material footprint, starting from the wealthy.

The ‘green growth camp’ also wants such a decrease, but it argues that GDP growth is necessary for – or compatible with – it. Degrowth, not: in all likelihood GDP will decrease too. If we do the right things to thrive, such as capping carbon, if we transform the profit economy to one of care and solidarity, the GDP economy will shrink. Kate too calls for ‘an economy that makes us thrive, whether or not it grows’ and to ‘free ourselves’ from the growth ‘lock-in’. The Germans named this ‘post-growth’ and I am fine with it. But somehow it beautifies the scale of the challenge: reducing our energy or material use in half and transforming and stabilizing a shrinking (not simply ‘not growing’) economy. With its shock element ‘de’-growth reminds that we won’t have our cake and eat it all.

2. Right conversations with the right people. Know this feeling ‘what am I doing with these people in the same room’? Hearing the words ‘win-win’ and looking at graphs where society, environment and economy embrace one another in loving triangles as markets internalize ‘externalities’ (sic)? Well, you won’t be invited to these rooms if you throw the missile of degrowth. And this is good. Marx wouldn’t be concerned with sitting at the table with capitalists to convince them about communism.

2. Right conversations with the right people. Know this feeling ‘what am I doing with these people in the same room’? Hearing the words ‘win-win’ and looking at graphs where society, environment and economy embrace one another in loving triangles as markets internalize ‘externalities’ (sic)? Well, you won’t be invited to these rooms if you throw the missile of degrowth. And this is good. Marx wouldn’t be concerned with sitting at the table with capitalists to convince them about communism.

Why pretend we agree? I’ve never had a boring or confusing conversation about degrowth (witness the present one). Passions run high, core questions are raised (did we loose something with progress? what is in the past for the future? is system change possible and how?). But to have these conversations you need to know about – and defend – degrowth.

3. Mission un-accomplished. Kate asks us to imagine that the ‘missile’ ‘has landed and it has worked’. Problem is the missile has landed, but it hasn’t worked, so it is not yet ‘the time to move on’. Microsoft spellcheck keeps correcting degrowth into ‘regrowth’. Degrowth is anathema to the right and left. Economists turn ash-faced when they hear ‘degrowth’. Eco-modernists capture the headlines with a cornucopian future powered by nuclear and fed by GMOs. A recent book calls degrowthers ‘Malthusians’, eco-austerians and ‘collapse porn addicts’. A radical party like Syriza had as slogan ‘growth or austerity’. The ideology of growth is stronger than ever. In the 70s its critique was widespread, politicians entertained it and at least economists felt they had to respond.

4. There is a vibrant community and this is an irreversible fact. In Barcelona 20-30 of us meet frequently to read and discuss degrowth, cook and drink, go to forests and to protests. We disagree in almost everything other than that degrowth brings us together. In the fourth international conference in Leipzig, there were 3500 participants. Most of them were students. After the closing plenary, they took to the shopping streets with a music band, raised placards against consumerism and blocked a coal factory. Young people from all over the world want to study degrowth in Barcelona. If you experience this incredible energy, you find that degrowth is a beautiful word. But I understand the difficulty of using it in a different context: half a year a visitor in London and I feel I am the odd and awkward one insisting on degrowth.

5. I come from the Mediterranean. Progress looks different; civilization there peaked centuries ago. Serge  Latouche says that ‘degrowth is seen as negative, something unpardonable in a society where at all costs one must ‘‘think positively’’’. ‘Be positive’ is a North-American invention. Please, let us be ‘negative’. I can’t take all that happiness. Grief, sacrifice, care, honour: life is not all about feeling ‘better’.

Latouche says that ‘degrowth is seen as negative, something unpardonable in a society where at all costs one must ‘‘think positively’’’. ‘Be positive’ is a North-American invention. Please, let us be ‘negative’. I can’t take all that happiness. Grief, sacrifice, care, honour: life is not all about feeling ‘better’.

For Southerners at heart – be it from the Global North or South, East or West – this idea of constant betterment and improvement has always seemed awkward. Wasting ourselves and our products irrationally, refusing to improve and be ‘useful’, has its allure. Denying our self-importance is an antidote to a Protestant ethic at the heart of growth. Let’s resist the demand to be positive!

6. I am not a linguist. Who am I to question Professor Lakoff that we can’t tell people ‘don’t think of an elephant!’ because they will think of one? Then again, a-theists did pretty well in their battle against gods. And so did those who wanted to abolish slavery. Or, unfortunately, conservatives for ‘deregulation’. By turning something negative into their rallying cry, they disarmed the taken-for-granted goodness of the claim of their enemy. The queer movement turned an insult into pride. This is the art of subversion. Is there a linguistic theory for it?

This is different from what Lakoff criticized US democrats for. Democrats accept the frame of Republicans, providing softer alternatives (‘less austerity’). ‘Green growth’ is that; degrowth is a subversive negation of growth: a snail, not a leaner elephant. Guardian’s language columnist Steven Poole finds degrowth ‘cute’. When most people agree with him, and find the snail cute, we will be on the path of a ‘great transition’.

7. Cannot be co-opted. Buen vivir sounds great. Who wouldn’t like to ‘live well’? And indeed Latin Americans took it at heart: the Brazil-Ecuador inter-Amazonian highway with implanted ‘creative cities’ in-between; Bolivia’s nuclear  power programme; and a credit card in Venezuela. All in the name of ‘buen vivir’. Which reminds me of ‘Ubuntu Cola’. No one would build a highway, a nuclear reactor, issue more credit or sell colas in the name of degrowth. As George Monbiot put it capitalism can sell everything, but not less.

power programme; and a credit card in Venezuela. All in the name of ‘buen vivir’. Which reminds me of ‘Ubuntu Cola’. No one would build a highway, a nuclear reactor, issue more credit or sell colas in the name of degrowth. As George Monbiot put it capitalism can sell everything, but not less.

Could degrowth be coopted by austerians? Plausible, but unlikely; austerity is always justified for the sake of growth. Capitalism looses legitimacy without growth. By anti-immigrants? Scary, but not impossible, it has been tried in France. This is why we cannot abandon the term: we have to develop and defend its content.

8. It is not an end. It is as absurd to degrow ad infinitum as it is to grow. The point is to abolish the god of Growth and construct a different society with low footprints. There is a ‘lighthouse’ for this: the Commons. A downscaled commons though. Peer-to-peer production or the sharing economy use materials and electricity too. Degrowth reminds that you cannot have your cake and eat it all, even if it’s a digitally fabricated one.

9. Focuses my research. I spend effort arguing with eco-modernists, green growthers, growth economists, or Marxist developmentalists about the (un)sustainability of growth. This persistence to defend degrowth is productive: it forces to research questions that no one else asks. Sure, we can in theory use fewer materials; but then why do material footprints still grow? What would work, social security, money, look like in an economy that contracts? One who is convinced of green growth won’t ask these questions.

Kate is not; she agrees with our 10 degrowth policy proposals: work-sharing, debt jubilee, public money, basic income. Why in the name of degrowth though she asks? Because we cannot afford to be agnostic. It makes a huge difference, both for research and design, whether you approach these as means of stimulus and growth anew or of managing and stabilizing degrowth.

Degrowth remains a necessary word.

Giorgos Kallis is ICREA professor of ecological economics in Barcelona and Leverhulme visiting professor at SOAS, London. He is the editor of Degrowth. A vocabulary for a new era (Routledge).

OK, so let’s have a vote (if only to get rid of the existing poll, which is out of date). Do you think degrowth is a) a good idea, but a bad word (Kate), b) a good idea and a good word (Giorgos) or c) not a good idea so the word is immaterial (me plus not sure about the politics of zero/negative growth)

Note: There is a poll embedded within this post, please visit the site to participate in this post's poll.

November 30, 2015

Why Degrowth has out-grown its own name. Guest post by Kate Raworth

My much-missed Exfam colleague Kate Raworth, now writing the book of her brilliant ‘Doughnut Economics’  paper and blog, returns to discuss degrowth. Tomorrow, Giorgos Kallis, the world’s leading academic on degrowth, responds.

paper and blog, returns to discuss degrowth. Tomorrow, Giorgos Kallis, the world’s leading academic on degrowth, responds.

Here’s what troubles me about degrowth: I just can’t bring myself to use the word.

Don’t get me wrong: I think the degrowth movement is addressing the most profound economic questions of our day. I believe that economies geared to pursue unending GDP growth will undermine the planetary life-support systems on which we fundamentally depend. That is why we need to transform the growth-addicted design of government, business and finance at the heart of our economies. From this standpoint, I share much of the degrowth movement’s analysis, and back its core policy recommendations.

It’s not the intellectual position I have a problem with. It’s the name.

Here are five reasons why.

Getting beyond missiles. My degrowth friends tell me that the word was chosen intentionally and provocatively as a ‘missile word’ to create debate. I get that, and agree that shock and dissonance can be valuable advocacy tools.

But in my experience of talking about possible economic futures with a wide range of people, the term ‘degrowth’ turns out to be a very particular kind of missile: a smoke bomb. Throw it into a conversation and it causes widespread confusion and mistaken assumptions.

Banksy says: choose your missile wisely

If you are trying to persuade someone that their growth-centric worldview is more than a little out of date, then it takes careful argument. But whenever the word ‘degrowth’ pops up, I find the rest of the conversation is spent clearing up misunderstandings about what it does or doesn’t mean. This is not an effective advocacy strategy for change. If we are serious about overturning the dominance of growth-centric economic thought, the word ‘degrowth’ just ain’t up to the task.

Defining degrowth. I have to admit I have never quite managed to pin down what the word means. According to degrowth.org, the term means ‘a downscaling of production and consumption that increases human well-being and enhances ecological conditions and equity on the planet.’ Sounding good, but that’s not clear enough.

Are we talking about degrowth of the economy’s material volume – the tonnes of stuff consumed – or degrowth of its monetary value, measured as GDP? That difference really matters, but it is too rarely spelled out.

If we are talking about downscaling material throughput, then even people in the ‘green growth’ camp would agree with that goal too, so degrowth needs to get more specific to mark itself out.

If it is downscaling GDP that we are talking about (and here, green growth and degrowth clearly part company), then does degrowth mean a freeze in GDP, a decrease in GDP, being indifferent about what happens to GDP, or in fact declaring that GDP should not be measured at all? I have heard all of these arguments made under the banner of degrowth, but they are very different, with very different strategic consequences. Without greater clarity, I don’t know how to use the word.

Learn from Lakoff: negative frames don’t win. The cognitive scientist George Lakoff is an authority on the nature and power of frames – the worldviews that we activate (usually without realizing it) through the words and metaphors we choose. As he has documented over many decades, we are unlikely to win a debate if we try to do so while still using our opponent’s frames. The title of his book, Don’t Think of an Elephant , makes this very point because it immediately makes you think of a you know what.

How does this work in politics? Take debates about taxes, for example. It’s hard to argue against ‘tax relief’ (aka tax cuts for the rich), since the positive frame of ‘relief’ sounds so very desirable: arguing against it just reinforces the frame that tax is a burden. Far wiser is to recast the issue in your own positive terms instead, say, by advocating for ‘tax justice’.

Does degrowth fall into this trap? I had the chance to put this question to George Lakoff himself in a recent webinar. He was criticizing the dominant economic frame of ‘growth’ so I asked him whether ‘degrowth’ was a useful alternative. “No it isn’t”, was his immediate reply, “First of all it’s like ‘Don’t think of an elephant!’ – ‘Don’t think of growth!’ It means we are going to activate the notion of growth. When you negate something you strengthen the concept.”

Just to be clear, I know that the degrowth movement stands for many positive and empowering things. The richly

Lakoff: “When you negate something you strengthen the concept”

nuanced book Degrowth: a vocabulary for a new era edited by Giacomo D’Alisa, Federico Demaria and Giorgos Kallis, is packed full of great entries on Environmental justice, Conviviality, Co-operatives, Simplicity, Autonomy, and Care – every one of them a positive frame. It’s not the contents but the ‘degrowth’ label on the jar that makes me baulk. I’ll adopt the rest of the vocabulary, just not the headline.

It’s time to clear the air. Just for a moment let’s give the word ‘degrowth’ the benefit of the doubt and suppose that the missile has landed and it has worked. The movement is growing and has websites, books and conferences dedicated to furthering its ideas. That’s great. These debates and alternative economic ideas are desperately needed. But there comes a time for the smoke to clear, and for a beacon to guide us all through the haze: something positive to aim for. Not a missile but a lighthouse. And we need to name the lighthouse.

In Latin America they call it buen vivir which literally translates as living well, but means so much more than that too. In Southern Africa they speak of Ubuntu, the belief in a universal bond of sharing that connects all humanity. Surely the English-speaking world – whose language has more than one million words – can have a crack at finding something equally inspiring. Of course this is not easy, but this is where the work is.

Tim Jackson has suggested prosperity, which literally means ‘things turning out as we hope for’. The new economics foundation – and many others – frame it as wellbeing. Christian Felber suggests Economy for the Common Good. Others (starting with Aristotle) go for human flourishing. I don’t think any of these have completely nailed it yet, but they are certainly heading in the right direction.

There’s too much at stake, and much to discuss. The debates currently being had under the banner of degrowth are among the most important economic debates for the 21st century. But most people don’t realize that because the name puts them off. We urgently need to articulate an alternative, positive vision of an economy in a way that is widely engaging. Here’s the best way I have come up with so far to say it:

We have an economy that needs to grow, whether or not it makes us thrive.

We need an economy that makes us thrive, whether or not it grows.

Is that ‘degrowth’? I don’t actually know. But what I do know is that whenever I frame it like this in debates, lots of people nod, and the discussion soon moves on to identifying how we are currently locked into a must-grow economy – through the current design of government, business, finance, and politics – and what it would take to free ourselves from that lock-in so that we can pursue social justice with ecological integrity instead.

We need to reframe this debate in a way that tempts many more people to get involved if we are ever to build the critical mass needed to change the dominant economic narrative.

So those are five reasons why I think degrowth has outgrown its own name.

I’m guessing that some of my degrowth friends will respond to this blog (my own little missile) with irritation, frustration or a sigh. Here we go again – we’ve got to explain the basics once more.

If so, take note. Because when you find yourself continually having to explain the basics and clear up repeated misunderstandings, it means there is something wrong with the way the ideas are being presented.

Believe me, the answer is in the name. It’s time for a new frame.

Kate Raworth is a renegade economist teaching at Oxford University’s Environmental Change Institute. She is currently writing Doughnut Economics: seven ways to think like a 21st century economist, to be published by Random House.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers