Duncan Green's Blog, page 152

November 16, 2015

What can we learn from Mexico’s tax on fizzy drinks?

Alice Evans

of

Cambridge University

looks for lessons from a small victory in the global struggle against obesity

We in the development industry are often frustrated by lack of government transparency, disregard of the evidence, and lack of political will to address major social problems.

Such obstacles are universal. Perhaps we might learn ‘how change happens’ (to use Duncan’s title) by comparing common processes in the Global North and South.

One global challenge is obesity. In the UK, it afflicts 25% of adults and costs the NHS £5.1bn every year. High sugar intake is a major factor, but despite this demonstrable causal link, the UK Government delayed publication of Public Health England’s recent report on how to curb sugar intake. That infuriated the Health Select Committee, which raised strong concerns about government interference and ideological aversions to a proposed sugar tax.

So what’s in this top secret report? Well, one of its recommendations is that we learn from Mexico, where purchases of sugar sweetened drinks fell (slightly) after the introduction of just such a tax.

Source: Al Jazeera

How did this come about? What is different about Mexico?

Maybe fizzy drinks weren’t all that popular to begin with? Perhaps it was less of a battle? Nope. The average Mexican drank 728 cans of Coca Cola branded drinks in 2012 alone.

Perhaps the sugary drinks industry is less influential in Mexico? Hardly. The closeness of industry and politics is embodied in Vicente Fox (President of Mexico from 2000 to 2006, and previously President of Coca-Cola Mexico). Several Mexican politicians certainly seem rather partial to the company: awarding it Mexico City’s ‘Health Conscious Organisation’ award. Indeed, Coca-Cola Mexico generously funds thousands of sporting events.

Culturally too, Coca-Cola is incredibly powerful. ‘Coke is used in religious rites; burping rids the body of evil spirits. In Chiapas highland churches, Coke bottles line the aisles and even decorate the altars’ – reports the Guardian.

Mexican civil society organisations, such as the Nutritional Health Alliance, struggled to compete with the deep pockets of the beverage industry. But help was at hand.

Having failed to ban large fizzy drinks cups in New York, Mayor Bloomberg’s charitable foundation decided to support

Photo by Jesus Villanueva

reform overseas. Bloomberg Philanthropies gave $16 million towards a campaign to reduce soda consumption in Mexico. Now there could be a fairer fight for hearts and minds.

Besides innovative street theatre (attracting media publicity), scary posters and subway billboards, the Nutritional Health Alliance also tried to buy airtime. Mexico’s major television networks refused, expressing concerns about upsetting importantly clients. So instead the ad – “see what the networks censored!” – was directly uploaded to YouTube, generating a quarter of a million hits. The Alliance also promoted the traditional Mesoamerican diet as healthy eating – literally ‘going with the grain’ [pun intended].

‘Would you give your children 12 spoonfuls of sugar?’

With widespread obesity imposing a growing burden on the underfunded health sector, the Mexican government became increasingly open to dialogue. The Ministry of Health appointed an expert panel to investigate the topic. Their findings were published in Mexico’s most widely read public health journal and widely shared in international scientific meetings, enabling collective discussion and reflection. Their recommendations were endorsed by Mexico’s Minister of Health.

Overtaking the U.S.A. to become the country with the world’s highest obesity rate was a shock that seems to have triggered growing government commitment to tackling obesity. This is encapsulated in the nationwide government-led media campaign entitled ‘Check yourself; Measure what you eat and Move!’.

In 2014, the Government enacted a 1 peso ($ 0.06) per litre tax on sugary fizzy drinks.

A fortnight ago that tax was halved, despite protests from the National Institute of Public Health. Public health groups and some opposition politicians accused lawmakers of ceding to pressure from industry (which claimed that 1,700 jobs had been lost).

A stark, cautionary tale of fragile gains.

So why did this (partial) success happen in Mexico but not elsewhere? One might speculate about the under-utilised power of social media and innovative framing. Or maybe this narrative indicates the need to strengthen and work with domestic academia, especially where it is underfunded (such as neoliberal Sub-Saharan Africa).

But do these factors explain political intransigence around the sugar tax in the UK? Not obviously. Is the British public less aware of the negative consequences of sugary diets? Are public health researchers more disconnected from policy makers? Neither sounds plausible. Maybe the UK government will become more responsive when we reach Mexican levels of obesity and struggling hospitals? (Not long now…!). Is it just an ideological difference between Mexican and UK ruling elites and/or publics? Or maybe Mexico and the UK are not all that different? After all, Mexico’s sugar tax has now been watered down… (admittedly awful pun intended).

I don’t have the answer. All I know (or at least think) is that we need to transcend this bizarre North-South divide and learn from shared, global experiences: such as obesity and also urban policy, neoliberalism and gender inequality. The question of ‘how change happens’ has a global remit. The current silos around North/South research aren’t helping anyone.

November 15, 2015

Links I Liked

Heavy on the video content this week – if you’re in the office, better get your earphones on

Consent, sex and tea: quintessentially British and rather effective [h/t Richard Cunliffe]

Last chance to vote in the Rusty Radiator awards for 2015’s worst aid charity video. Amazingly, they found one that’s even worse than Band Aid. As for the Golden Radiator awards (for best video), very hard to choose between 3 excellent candidates, but I voted for this one (cos it made me laugh).

Nerd heaven: 175 new development economics papers summarized, tagged and categorized by theme, from the World Bank’s amazing David Evans

Geeky but useful. Adapting the principles for digital development for knowledge management.

Geeky but useful. Adapting the principles for digital development for knowledge management.

This World War II guide to saboteurs on undermining organizations from within probably describes your office meetings all too well. [h/t Chris Blattman] fortune.com/2015/09/30/wor…

Proof is piling up that private sector finance is not an easy development fix, so why are donors, including the UK government, still so keen?

Attitudes to aid in donor and recipient countries – some surprises here

hmmm. Couldn’t pin down why this BOND (UK NGO coalition) spoof on poverty porn didn’t work, but I wasn’t alone: Alanna Shaikh ‘I want to like it but I just don’t.’

Best of the lot. Bye Bye #Ebola. Sierra Leonean rapper, Block Jones, with a wonderful celebratory 3m video on the nightmare’s end. Beautiful.

November 12, 2015

Why being scooped by Piketty is no bad thing for Oxfam (but what will the government of India think?)

Guest post from Tim Gore, Oxfam’s climate change policy czar

No-one likes to be scooped, least of all researchers who have battled through Oxfam’s internal sign-off process. But when the authors who beat you to the publication punch include one of the most famous economists in the world – as we experienced last week – we can at least be reassured that our analysis is on the right track.

Thomas Piketty and Lucas Chancel have just published an excellent paper assessing the global inequality of carbon consumption. We’ve done the same thing, but our paper is due for release during the first week of the Paris COP. Both studies apply a simple elasticity model to data on the global distribution of income, allocating estimates of national emissions consumption to richer and poorer citizens within countries.

This allows us both to show the shocking extent of global inequality of carbon consumption and that within (notably middle income) countries. Reassuringly for our number-crunching skills, even if frustratingly for our media hits, we find very similar results. The Piketty/Chancel paper suggests the top 10% highest emitters in the world are responsible for 45% of global emissions, the bottom 50% for 13%. Our numbers are in the same ballpark, with a slightly more pronounced gap.

This allows us both to show the shocking extent of global inequality of carbon consumption and that within (notably middle income) countries. Reassuringly for our number-crunching skills, even if frustratingly for our media hits, we find very similar results. The Piketty/Chancel paper suggests the top 10% highest emitters in the world are responsible for 45% of global emissions, the bottom 50% for 13%. Our numbers are in the same ballpark, with a slightly more pronounced gap.

Clearly we agree on a few important things. Firstly, that carbon inequality is extreme and that tackling it is key to fighting climate change. Secondly, that high emitters should in principle be treated alike, wherever they happen to live.

But while the Piketty/Chancel paper focuses on the policy implications of their findings for the top end of the global distribution, ours is more interested in the bottom. These are largely complementary approaches, but they do lead to some different policy conclusions, which are highly pertinent to one of the most contentious issues on the table in Paris.

Piketty and Chancel propose various forms of progressive carbon taxation on high emitters to fund global adaptation  efforts. Under their preferred scheme in which contributions are split between individuals in the top 10% of world emitters, North America would contribute 46%, EU 16% and China 12% of the total.

efforts. Under their preferred scheme in which contributions are split between individuals in the top 10% of world emitters, North America would contribute 46%, EU 16% and China 12% of the total.

We’ve certainly made our fair share of proposals for innovative ways to close the gap in adaptation finance (here, here, here). But we might struggle to make the case for this one in the G77 group of developing countries. Here’s why.

Right now rich countries are demanding an expansion of the pool of climate finance contributors as a trade-off for making any new finance commitments in Paris. The essential choice for ministers at the COP will be between language that encourages new countries to contribute that are “in a position to do so” (supported by the rich countries and some others) and those that are “willing to do so” (the maximum the Indian government amongst others seems prepared to consider, as floated by China). Expect that one to go to the last night.

Official negotiating text for Paris showing options – “in a position to do so” vs “willing to do so”. Lawyers licking their lips on billable negotiating time…..

Oxfam and Piketty and Chancel would agree more objective indicators are vital to guide equitable effort sharing of climate finance – as suggested by the “in a position to do so” formulation. But the question Piketty and Chancel have to answer is whether the presence of a share of the world’s very highest emitters is a sufficient indicator of a country’s capacity to contribute.

As our studies make clear, many of the middle income countries that are being squeezed for new contributions are now not only home to a share of the highest emitters in the world, but also to most of the lowest. Indeed the vast majority of the lowest 50% live in India and China. As we’ve argued before (here and here), only countries that have the capacity to tackle their domestic poverty challenges should be expected to contribute to international adaptation funds, and on that score the middle income countries look very different.

There’s no question rich high emitters should be paying for their emissions wherever they live, and that the revenues  should be redistributed to benefit the poorest and least emitting. But for some countries, like India, that should be a primarily domestic affair (as I suggested for South Africa here). For others, like Brazil, Singapore or South Korea, it’s time to step up on the global stage. China has recently pledged $3.1bn themselves, though in bilateral South-South flows.

should be redistributed to benefit the poorest and least emitting. But for some countries, like India, that should be a primarily domestic affair (as I suggested for South Africa here). For others, like Brazil, Singapore or South Korea, it’s time to step up on the global stage. China has recently pledged $3.1bn themselves, though in bilateral South-South flows.

So where does that leave the government of India reading our studies? They should be reassured with our findings that the vast majority of Indians are very low emitters by global standards (we’ll have some more specific comparisons between countries in our paper).

They may though see the Piketty/Chancel paper as exactly the sort of argument they fear will be used to press them into making contributions in the years ahead (even though they are clear rich countries would hugely increase contributions under their proposals). We would argue that the presence of rich emitters in their population is not the only test of whether they are “in a position” to contribute, and thus that they have nothing to fear from objective indicators.

We’re looking forward to continuing to work with Piketty and Chancel and any others interested in progressing these debates in Paris and beyond, there’s much more to be said about all this. It’s clear we are pushing in the same direction, and in terms of achieving the changes Oxfam wants to see in the world, it’s working in such alliances that ultimately matters more than securing a splash of headlines from a new report on launch day.

November 11, 2015

How do developing country decision makers rate aid donors? Great new data (shame about the comms)

Brilliant. Someone’s finally done it. For years I’ve been moaning on about how no-one ever asks developing country

Anyone ever asked her?

governments to assess aid donors (rather than the other way around), and then publishes a league table of the good, the bad and the seriously ugly. Now AidData has released ‘Listening To Leaders: Which Development Partners Do They Prefer And Why?’ based on an online survey of 6,750 development policymakers and practitioners in 126 low and middle income countries. To my untutored eye the methodology looks pretty rigorous, but geeks can see for themselves here.

Unfortunately it hides its light under a very large bushel: the executive summary is 29 pages long, and the interesting stuff is sometimes lost in the welter of data. Perhaps they should have read Oxfam’s new guide to writing good exec sums, which went up last week.

So here’s my exec sum of the exec sum.

The setting: ‘Once the exclusive province of technocrats in advanced economies, the market for advice and assistance has become a crowded bazaar teeming with bilateral aid agencies, multilateral development banks, civil society organizations and think tanks competing for the limited time and attention of decision-makers.

Development partners bring an increasingly diverse set of wares to market, including: impact evaluations, cross-country benchmarking exercises, in-depth country diagnostics, “just-in-time” policy analysis and advice, South-South training and twinning programs, peer-to-peer learning networks, “engaged advisory services”, and traditional technical assistance programs. Yet, we know remarkably little about how the buyers in this market – public sector leaders from low and middle-income countries – choose their suppliers and value the advice they receive.’

The Findings: Sorry DFID/USAID, but ‘Host government officials rate multilaterals more favorably than DAC and non-DAC development partners on all three dimensions of performance: usefulness of policy advice, agenda-setting influence, and helpfulness during reform implementation. The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, the GAVI Alliance, and the World Bank rank among the top 10 development partners on all three of these metrics.’

The Findings: Sorry DFID/USAID, but ‘Host government officials rate multilaterals more favorably than DAC and non-DAC development partners on all three dimensions of performance: usefulness of policy advice, agenda-setting influence, and helpfulness during reform implementation. The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, the GAVI Alliance, and the World Bank rank among the top 10 development partners on all three of these metrics.’

The Old Boys network is alive and kicking: ‘Host government officials who have previously worked for a development partner usually regard their policy advice as being useful’. Perhaps connected to that, the fear of China sweeping the rest of the aid business aside appears overblown (see fig).

Listening more to developing countries gets more results than forcefeeding them through ‘technical assistance’ programmes: a big econometric data crunch found that: ‘Alignment with partner country priorities is positively correlated with the extent to which development partners influence government reforms. This finding suggests that when development partners put the country ownership principle into practice, they usually reap an influence dividend. [Whereas] Reliance upon technical assistance undermines a development partner’s ability to shape and implement host government reform efforts. The share of official development assistance (ODA) allocated to technical assistance is negatively correlated with all three indicators of development partner performance.’

All good stuff, but I really had to dig to extract these messages. And the report misses the biggest of all tricks – where is the league table? If there’s one thing that’s guaranteed to get the attention of policy makers, it’s finding that they are languishing at the bottom of a table of their peers. The data gathered here could easily be combined to produce an overall table of how different aid providers rank in the eyes of their recipients across a number of factors.

A quick exchange of emails with an understandably unhappy (with this review) AidData established that they did in fact produce a league table after all. But it’s on page 82 of the appendices, under the title ‘Appendix E: Supplemental information.’ At this point, the report starts to look like a classic comms case study, and not in a good way.

So here’s the top 20 on what for me is the most interesting questions. British readers please note, DFID doesn’t make the cut – it’s at 31, 35 and 40 in the 3 columns.

The good news is that AidData is planning similar exercises in 2016 and 2018. Let’s hope they sort out some of the teething troubles with their comms (I’m sure Oxfam would be happy to help), so that they make the most of a great idea, a huge amount of hard work and some brilliant data.

More coverage in the Washington Post.

November 10, 2015

A big win for climate change campaigners in the Philippines – how did they do it?

Some great news from the Philippines. The Philippines Survival Fund, which I blogged about a couple of years ago, is  finally open for business – local governments and community organizations will now be apply to apply for funds up to 1 billion pesos (US$21m) a year, for projects that help communities adapt to climate change.

finally open for business – local governments and community organizations will now be apply to apply for funds up to 1 billion pesos (US$21m) a year, for projects that help communities adapt to climate change.

The first lesson is the need for stamina – even on an apparently ‘quick win’ like the PSF (the law was passed after only a year of campaigning) it took a further three years to get government and all stakeholders to design its business procedures.

So what happened? This from an internal Oxfam case study (why don’t we publish these things? Drives me crazy).

In 2010, Oxfam and its partner the iCSC (Institute for Climate and Sustainable Cities) commissioned a piece of research which revealed that the majority of public climate spending was going towards mitigation rather than adaptation. It recommended that an adaptation fund be created to incentivize and scale-up adaptation actions by local governments and communities.

Oxfam joined with two of its partners who came together to campaign for an adaptation fund, named the “People’s Survival Fund” (PSF). This core group gradually grew into a coalition of organisations who brought together different expertise, connections and constituencies.

Oxfam joined with two of its partners who came together to campaign for an adaptation fund, named the “People’s Survival Fund” (PSF). This core group gradually grew into a coalition of organisations who brought together different expertise, connections and constituencies.

Members of the coalition began by developing, and regularly updating, a detailed power analysis which underpinned the campaign strategy. This was crucial in helping the coalition identify potential allies and blockers, guide their political actions & determine how to adapt their tactics.

Oxfam led the policy analysis that informed the development of the PSF, connecting up with livelihoods and humanitarian programme staff at the national level, as well as with colleagues at the global level who were working on climate finance issues, to develop policy proposals and briefings. This was accompanied by persistent lobbying in Congress, based on working with carefully selected and powerful champions of the campaign who could manoeuvre around those blocking the initiative.

This behind the scenes work was backed-up by strong public facing and media work to increase awareness of the PSF and mobilize public support. This included policy forums, exhibitions, social media actions, popular music events and work with opinion leaders and celebrities, like the superstar Filipino boxer Manny Pacquiáo (signing up, right), who  brought enormous visibility to the campaign.

brought enormous visibility to the campaign.

What was the Campaign’s Theory of Change?

Power analysis: Key to the success of this work was having a strong power analysis from the beginning, which

provided the coalition with a solid understanding of the political panorama and where the balances of power lay. This was crucial in facilitating the identification of potential allies and blockers, guiding the campaign’s political actions & determining how to adapt their tactics.

Windows of opportunity: This also enabled the campaign to take advantage of windows of opportunity that presented themselves. A number of natural disasters took place during the lifespan of the campaign which the coalition used to highlight the urgency of a PSF. They also made use of a political scandal (impeachment) to build political alliances in the senate while attention was elsewhere, thus building the support they needed to push the process forward.

Local to global: Internally, the campaign managed to be nationally relevant while plugging into the global campaign and global resources. This also meant that it could draw on support from across Oxfam while maintaining the leadership and decision-making with the core campaigns group in country.

Flexible funding: Oxfam spent approximately £112,000 (including national staffing costs) on this campaign over its two year lifespan. The staffing costs were covered by unrestricted funds at the national level, which ensured that the campaign had the staffing capacity needed to make it a success, as well as access to flexible and fast funding to draw on at opportune moments. Some of the campaign activities were covered by global funds earmarked for climate change related campaign work.

Evidence based: The campaign was strongly rooted in evidence generated from Oxfam’s development and humanitarian programmes, which included gendered analysis from the very beginning. This helped build support for the campaign from local authorities and decision makers, build the legitimacy of the campaign and ensure complementarity and coherency between the programmes in country. The campaign was supported and carried by Oxfam’s development and humanitarian work, with the country team coming together to conduct joint public events.

Evidence based: The campaign was strongly rooted in evidence generated from Oxfam’s development and humanitarian programmes, which included gendered analysis from the very beginning. This helped build support for the campaign from local authorities and decision makers, build the legitimacy of the campaign and ensure complementarity and coherency between the programmes in country. The campaign was supported and carried by Oxfam’s development and humanitarian work, with the country team coming together to conduct joint public events.

Great stuff – I scandalised the team and our evaluation wallahs by doing a simplistic Return on Investment calculation. $21m a year is a pretty good return on a £112,000 campaign: I got a 68:1 ratio, even after making some allowances – sorry, but I’m sticking with it!

November 9, 2015

Great new IMF paper puts women’s rights at the heart of tackling income inequality

The IMF continues to surprise an old lag like me who cut his policy teeth condemning it as the incarnation of extreme

market idolatry and anti-poor structural adjustment programmes in the 80s and 90s. Read its new ‘staff discussion note’, Catalyst for Change: Empowering Women and Tackling Income Inequality to see why.

The authors point out that ‘Income inequality and gender-related inequality can interact through a number of channels. First, gender wage gaps directly contribute to income inequality. Furthermore, higher gaps in labor force participation rates between men and women are likely to result in inequality of earnings between sexes, thus creating and exacerbating income inequality. Differences in economic outcomes may be a consequence of unequal opportunities and enabling conditions for men and women, and boys and girls.’

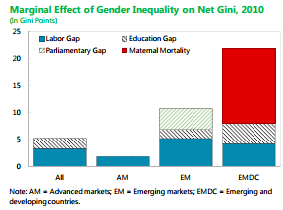

The paper crunches the data in typical IMF fashion and finds that it’s all true: ‘gender inequality is strongly associated with income inequality….. These results hold for countries across all levels of development, however the relevant dimensions of gender inequality vary. For advanced countries—with largely closed gender gaps in education and more equal economic opportunities across sexes— income inequality arises mainly through gender gaps in economic participation. In emerging markets and low-income countries, inequality of opportunity, in particular gender gaps in education and health, appear to pose the main obstacle to a more equal income distribution.’ You got that? The big driver of gender inequality in poor countries is education and healthcare, not just getting women into paid work. They illustrate this with a break down of causes of gender income inequality (not entirely sure, but I think ‘maternal mortality’ is a proxy variable for healthcare in general).

You got that? The big driver of gender inequality in poor countries is education and healthcare, not just getting women into paid work. They illustrate this with a break down of causes of gender income inequality (not entirely sure, but I think ‘maternal mortality’ is a proxy variable for healthcare in general).

The most powerful section is the policy recommendations:

‘Redistribution complements but is not a substitute for gender-specific policies geared to reducing gender and income inequality. Previous IMF work has shown that redistribution generally has a benign effect on growth, and is only negatively related to growth in the most strongly redistributive countries. Therefore, redistributive policies can help lower income inequality directly and if not excessive be pro-growth. However, in order to ameliorate deeper inequality of opportunities, such as unequal access to the labor force, health, education and financial access between men and women, more targeted policy interventions are needed as a complement to redistribution. Some of these policy options are discussed in the remainder of this section.

A significant decrease in gender gaps will require work on many dimensions.’

And they go on to list them:

Remove gender-based legal restrictions

Create fiscal space for priority expenditures: education, infrastructure like roads and electrification, and access to health services

Revise tax policies (eg tax credits and benefits for low wage earners, mainly female)

Implement well-designed family benefits (eg parental leave, childcare, flexible work)

Gender Budgeting ‘examines the gender impact of government expenditures, policies, and programs and can reduce gender inequalities in education, employment, and health outcomes, among other measures.’

Make finance accessible to women.

So what are the flaws? I sent my comments to our gender team, and got some interesting thoughts on the ‘what’s  missing’ – always the hardest bit to identify in any report. This from Francesca Rhodes, Irene Muñoz and Kim Henderson:

missing’ – always the hardest bit to identify in any report. This from Francesca Rhodes, Irene Muñoz and Kim Henderson:

‘Overall we would say the focus continues to be on individual women, rather than the approach taken by UN Women in their ‘Progress’ report on changing the way the economy is organised to support human rights and gender equality (through macroeconomic policy, labour market regulation, social transfers, raising and spending more public resources in gender responsive way).

The top three asks from Diane Elson in this area are:

Demand a living wage

2. Increase support for women’s organisations

3. Improve public services and infrastructure funded with gender responsive tax

The IMF touch on the last one, and note minimum wages are related to reduced income inequality, but there is no call for living wages, which would benefit many women and reduce gender and income inequality. And no comment on women’s and women’s rights organization’s agency as key to support changes in gender equality – which may not be the role of the IMF to support, but they could comment. So we welcome and it’s interesting to see the IMF discussing gender in this way, and we hope to see the policies and lending practices of the IMF change to take this approach into account, especially on monitoring the impact of economic policies on women and girls. However we continue to have concerns the recommendations don’t go far enough to be transformative.’

But part of me is still pinching myself and saying ‘can we really be having this conversation about the IMF?’ Or hearing its boss talk about gender inequality as she opens Oxfam’s new office in Washington? Amazing how far it has come in a relatively short space of time.

November 8, 2015

Links I Liked

Powerful, harrowing photo essay of Syrian refugee children asleep.

Suffragettes v suffragists. Nice movie, shame about the (lack of) theory of change – it was really the suffragists wot won it

Oxfam America takes on Big Chicken in the US, using leader/laggard tactics to push for a better deal for 250,000 workers and getting some very quick wins

Remember all that guff about the state getting out of the way, in order to unleash entrepreneurs like Steve Jobs? Every major technology in the iPhone came from the US government or other state bodies. Cool infographic from  Mariana Mazzucato [h/t Michael Shellenberger]

Mariana Mazzucato [h/t Michael Shellenberger]

Thomas Piketty proposes flight tax (just business class) to raise climate funds

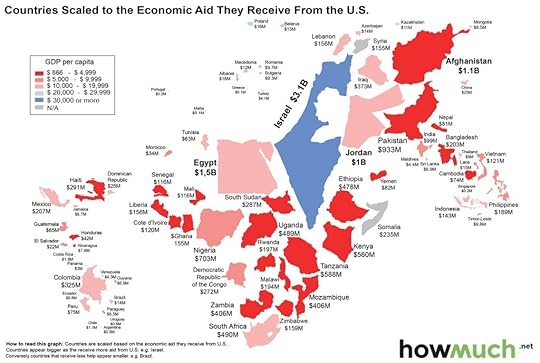

Politics of US aid: countries rescaled according to how much US aid money they receive. Guess what, the connection to poverty is minimal

Check out the new Oxfam research guidelines on focus groups, surveys and writing executive summaries

Afghan Imams defy the Taliban to encourage access to contraception

November 5, 2015

5 times bigger than aid: important new research on drugs as a (missing) development issue

A couple of years ago I reported on an excellent meeting at Christian Aid on drugs as a development issue. They have  continued that work and today published an important new paper by Eric Gutierrez, ‘Drugs and Illicit Practices: assessing their impact on development and governance’.

continued that work and today published an important new paper by Eric Gutierrez, ‘Drugs and Illicit Practices: assessing their impact on development and governance’.

The paper argues that the illicit drug trade is a ‘major blind spot in development thinking’, and uses in-depth case studies from Afghanistan, Colombia, Mali and Tajikistan to explore the issues. Some highlights:

Scale: Even on its own terms, the ‘war on drugs’ clearly isn’t working – the international illicit drug trade is now worth an estimated $449bn to $674bn a year (UN figures), up to five times more than the global aid budget.

The problem: ‘Rather than recognise the fact that the illicit drugs trade is woven into the very fabric of many societies, the prevailing counternarcotics narrative and the core analysis of the UN law enforcement system treats it as a separable problem – something akin to a malignant tumour that can be isolated and surgically removed from a healthy body. Law enforcement is seen as the cure and its success is measured in metrics such as raids conducted, kilograms seized, convictions won.’

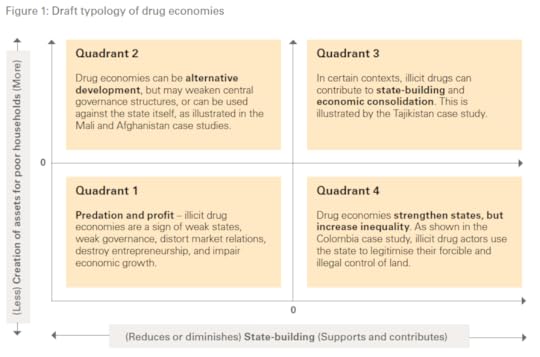

The report argues that part of the problem is that the development sector has opted out and left it to the law enforcement people. On the basis of the case studies, it develops a 2×2 ‘typology of drug economies’, with the axes determined by how much the drugs trade strengthens/weakens the state, and how much it strengthens/weakens the livelihoods of the poor. See diagram.

‘With most of the world’s focus on quadrant 1, the three other quadrants, and what could be appropriate policy responses for each, have been largely ignored. Illicit drugs – like any other lucrative cash crop or natural resource for export – can actually be useful, in a perverse way, for both state-building and economic consolidation, as the case of Tajikistan demonstrates. Drugs production and trafficking can bring ‘alternative development’, even as it weakens governance structures, as shown in the Mali and Afghanistan case studies. Finally, the Colombia case study illustrates that, like any other profit-making enterprise, the illicit drugs trade can concentrate the benefits of growth in the hands of a few and thus increase inequality and perpetuate poverty.’

This typology is still a work in progress, but its initial conclusions are:

‘The ability of poor households to cling to a lifeline for survival – such as illicit drug crop cultivation – seems to depend on agreements made with more powerful local actors advancing their own agendas.

‘The ability of poor households to cling to a lifeline for survival – such as illicit drug crop cultivation – seems to depend on agreements made with more powerful local actors advancing their own agendas.It is land-poor households who end up opening up more land for cultivating illicit drug crops.

In places affected by conflict, clear distinctions need to be made between shadow, combat and coping economies.

The collusion and complicity of poor households in illicit activity needs to be understood in the context of constant insecurity and the sheer lack of protection.

Those engaged in illicit activity – from corrupt public officials to warlords and drug lords – may be despised as criminals and bad guys, but they can still win the vote and promote security and stability.

Even the most notorious can still enjoy some form of legitimacy. But legitimacy can be quickly lost too. In the end, legitimacy is ultimately shaped by rival institutions – clan, ethnic, national, or political and other group agendas.

Illicit activity and actors, often thought of as operating outside the state and the formal economy, are often inseparable from it. They are not necessarily anti-state and anti-development, and can be involved as well in wealth creation.

It is quite clear that debate is not simply about prohibition versus legalisation – in between these two positions is a wide range of thinking that does not necessarily support either. Instead, many of these views take a position that prohibition has failed or is failing, and that local contexts should be driving much of the policy’

The report sets out a whole range of issues that development agencies could/should take up if they want to respond to drugs as a development issue. These include recognizing the importance of protection and security for poor people; challenging the narrow focus ‘alternative development’ on crop substitution programmes, rather than wider rural development issues; the importance of land rights and land grabs; and the need to understand better the trade’s impact on women (it fesses up to a blind spot there).

Well worth reading – kudos to Christian Aid and its partners for pushing this work along.

November 4, 2015

Is China’s rise relevant to today’s poorest states?

Am I allowed to say that a meeting held under Chatham House Rules took place at Chatham House? Let’s risk it. I

UK Development Minister Justin Greening and China’s Commerce Minister Gao Hucheng seal the deal while their bosses look on

recently attended a fascinating conference on UK-China relations, which discussed the two governments’ burgeoning cooperation on development issues. This seems to be turning into a triangular relationship, in which the UK and China combine brains, money and experience to jointly support other countries’ development efforts in a few specific areas (jobs and growth, health, disasters and girls/women).

A key player in all this is China’s Development Research Center, a state thinktank (it reports to the State Council) that is rapidly evolving from an exclusive focus on development within China to take a more international role.

The DRC will host the new Center for International Knowledge on Development (CIKD) announced by President Xi at the New York summit in September, which will ‘facilitate studies and exchange regarding theories and practices of development suited to each country’s respective national conditions.’ DFID is backing the CIKD as part of a 5 year partnership programme that will ‘support high level policy research on China’s development models, China’s role in global governance, and improving policy coherence for international development and other areas of mutual interests.’

It was a fascinating chance to try and see development through the eyes of some of China’s leading minds on a range of issues. Some of the main impressions :

An interesting tension between an understandable level of triumphalism (getting 600m people out of poverty in the last four decades is not something any other country can boast) and caution. As one speaker pointed out, China developed by finding its own path, not by following the advice of outsiders, so how could it possibly switch roles and start telling other countries what to do? And to be useful, any account of China’s successes will have to be honest on the ‘warts and all’, acknowledging the importance of mistakes, and China’s ability to learn from them (eg the retreat over the last 10 years from a disastrous health privatization process).

An interesting tension between an understandable level of triumphalism (getting 600m people out of poverty in the last four decades is not something any other country can boast) and caution. As one speaker pointed out, China developed by finding its own path, not by following the advice of outsiders, so how could it possibly switch roles and start telling other countries what to do? And to be useful, any account of China’s successes will have to be honest on the ‘warts and all’, acknowledging the importance of mistakes, and China’s ability to learn from them (eg the retreat over the last 10 years from a disastrous health privatization process).

Real questions on the relevance of China’s experience to fragile states. A large amount of the discussion assumed the existence of a state committed to pursuing development – that allows everyone to relax and start discussing the evidence for this or that policy decision. But an increasing focus of aid over the coming decades will be on fragile states, where governments are either absent or largely predatory. As the whole ‘Doing Development Differently’ and ‘Thinking and Working Politically’ movement has shown after two decades of bitter experience, technocratic advice and training workshops don’t get very far in such settings. Could China look into its past and find examples of fragile state turnarounds at national or subnational level? Are China’s aid officials actually able to talk about politics, power, governance etc? I have some serious doubts here.

The gulf in language is fascinating: British aid officials talk of jobs, growth and governance; their Chinese counterparts

talk of harmony, cohesion, balance and inequality. Some of this difference may be superficial, euphemistic or misleading, but I think it goes deeper than that – caricaturing greatly, China’s vision of development is fundamentally collective, while the UK’s is individualist. Discuss. Other linguistic differences are equally revealing: I couldn’t work out why an official replying to a question about civil society started talking about the private sector, until my Chinese neighbour explained to me that such is the power of the state in China, that anything outside the state (civil society, private sector) is lumped together by officials.

And one brilliant conversation on the margins: a senior Chinese researcher trying to work out how to tackle petty corruption in the government. When are amnesties effective? How to gain public support for the wage increases that would help reduce the incentives for officials to demand bribes? I couldn’t resist comparing it to the public’s refusal to raise UK MPs’ wages, which led in part to the expenses scandal…..

November 3, 2015

Doing Development Differently: a great discussion on Adaptive Management (no, really)

Went to a fascinating workshop last week on ‘adaptive management’ hosted and designed by USAID as part of their work on  Knowledge, Information and Data (see final para for more links) and facilitated by Ben Ramalingam, who has just started at IDS as their new digital, technology and innovation czar. A whole load of participants are going to write posts for this blog, which will go up over the next few weeks, but I thought I’d kick off with some personal impressions, not least because I’m doing a ‘brown bag’ staff talk today at USAID in Washington (on How Change Happens, what else?).

Knowledge, Information and Data (see final para for more links) and facilitated by Ben Ramalingam, who has just started at IDS as their new digital, technology and innovation czar. A whole load of participants are going to write posts for this blog, which will go up over the next few weeks, but I thought I’d kick off with some personal impressions, not least because I’m doing a ‘brown bag’ staff talk today at USAID in Washington (on How Change Happens, what else?).

Firstly, what is adaptive management? According to Ben ‘It’s all about interaction and change: change is emergent and contextual; it relies on organizations having the right capacities and processes to generate novelty in day to day performance. It means bosses trusting people closer to the problem. In contrast ‘traditional management’ assumes you have the answers and you need to get them into place at the right time. AM assumes you don’t have the answers, and need a system to generate them as and when they are needed in any given context.’

Second, USAID’s explanation for why they schlepped all the way to London to discuss this was that much of the interesting discussion on smart/adaptive development is happening in the UK – see my earlier musings on whether Britain has become some kind of silicon valley-type cluster on aid and development.

Third, pleasingly inter-disciplinary – tech geeks, development programme people, donors, M&E types, academics, behavioural psychs, private sector entrepreneurs – and a great mix of creative tools and methods employed by Ben, from story telling to participatory games to consensus methodologies. That’s particularly important when people come from different disciplines, each with their own jargon, assumptions etc.

Fourth, I’m not a big fan of diagrams, especially the overcomplicated theory of change spaghetti variety, but two emerged in the discussions that really got me thinking.

The first, in a conversation with Robert Chambers, was a ‘data, adaptive management, participation’ triptych. Promising because each of the three points of the triangle compensate for the weaknesses of the other – participatory approaches ensure data is bottom up and relevant to people on the ground, not an exercise in extraction; and that adaptive management approaches don’t degenerate into more effective manipulation (see my concerns on the Doing Development Differently agenda); good data enhances both management and participation; adaptive approaches prevent rigidity creeping into data systems or participatory methods.

The second diagram emerged from a competition to develop a shareable framework on AM, and manages to get  beyond ‘are you for adaptation or logframes?’ polarities, by seeking to locate different approaches according to whether we have high/low levels of knowledge of the context in which we are intervening, or of the causative impact of a given intervention. That generates a handy 2×2: if you have high knowledge of both causation and context, then you can stick with traditional programming approaches; if you have good knowledge of causation, but context is uncertain or rapidly changing, the key is to have fast feedback and response systems in place, eg when doing cash transfers in a fragile state. If you have good knowledge of the context but are unsure on the causation, try lots of things – experimentation, monitor their impact, adapt and iterate (Matt Andrews’ problem driven iterative adaptation). If you have neither, try and escape from the bottom left quadrant by either finding a simple intervention that works (cash transfers again) or studying the context to get you towards the bottom right.

beyond ‘are you for adaptation or logframes?’ polarities, by seeking to locate different approaches according to whether we have high/low levels of knowledge of the context in which we are intervening, or of the causative impact of a given intervention. That generates a handy 2×2: if you have high knowledge of both causation and context, then you can stick with traditional programming approaches; if you have good knowledge of causation, but context is uncertain or rapidly changing, the key is to have fast feedback and response systems in place, eg when doing cash transfers in a fragile state. If you have good knowledge of the context but are unsure on the causation, try lots of things – experimentation, monitor their impact, adapt and iterate (Matt Andrews’ problem driven iterative adaptation). If you have neither, try and escape from the bottom left quadrant by either finding a simple intervention that works (cash transfers again) or studying the context to get you towards the bottom right.

What do you think?

My overriding impression, which I shared in my closing remarks for the event, was that all of us pushing for adaptive development approaches should be thinking harder and smarter about how to change the aid sector. When we try and change the world we use a whole range of advocacy tactics that we know have worked in the past (eg finding champions, seizing windows of opportunity). And yet all too often we assume changing our sector is more of a technical endeavour (‘just show ‘em the evidence’). In its cross-disciplinary, dialogue-focused approach, this workshop was a great step towards a more collective approach to such change (building coalitions of ‘unusual suspects’ is another successful advocacy tactic) – let’s see if we can capitalise on it.

Last but not least – some cracking one-liners:

‘There are three kinds of social scientists: the ones who can count, and the ones that can’t’ (Robert Chambers)

‘Big Data is like teenage sex – everyone is talking about it, no-one knows how to do it, everyone thinks everyone else is doing it, so everyone claims to be doing it themselves’ (Ben R, definitely going to nick that and replace big data with theories of change…)

If you want to know more about USAID’s thinking on this, try this paper on its Ebola response, its Learning Lab or throw your hat into the ring for its Request for Proposals (RFP) on “Adaptive Programming Using Real-Time Data“, the deadline for which has just been extended to 20th November.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers