Duncan Green's Blog, page 155

October 7, 2015

What are governance advisers missing with ‘Political Economy Analysis’? How can they do better?

From a restaurant in Jakarta, David Hudson & Heather Marquette with some new thinking on power, politics and

governance

governance

What advice would you give to a novice governance advisor working for a bilateral donor going into the field for the first time? Want to know how some of the top governance experts, advisors, researchers and academics would say? Well, wonder no more.

In a welcome departure, the OECD-DAC’s Governance Network (GovNET) has ditched the usual dull formal format for something slightly more interesting. The new A Governance Practitioner’s Notebook: Alternative Ideas and Approaches is guidance but not as we know it. The book’s premise is that there is a new governance advisor named ‘Lucy’, and our job as authors is to provide real-life support and guidance to her as she gets her head around her new job. Not the ‘official’ line coming from HR or Heads of Profession but the kind of advice she may really need before taking up her first country posting. The volume includes chapters from the likes of Matt Andrews, David Booth, Thomas Carothers, and Sue Unsworth, as well as some highly experienced practitioners. And some of it is even funny.

A couple of months before a trip to Indonesia/Myanmar/Australia, and all points in between, we’d been asked to contribute a chapter. The book was pitched to us as an ‘alternative guide to Political Economy Analysis (PEA)’. We were given carte blanche to be critical and provocative and to reflect on our own experiences with PEA and what we thought was missing.

One warm night in Jakarta, we faced the stark realisation that we’d somehow chosen to take a taxi some distance out  to a dry restaurant. Not a drop of alcohol on the menu and nothing to do other than reflect on what we’d observed after spending time with a number of impressive DFAT, DFID and Asia Foundation folks working on a range of different development programmes. In meeting after meeting, we heard about people ‘thinking and working politically’ (TWP) in all sorts of ways: finding innovative ways to better support women parliamentarians; thinking through implementation of the new ‘Village Law’, designed to bring more financial resources and control to the microlevel; better integrating health and education reforms to tackle HIV; harnessing youth engagement and social media to fight corruption.

to a dry restaurant. Not a drop of alcohol on the menu and nothing to do other than reflect on what we’d observed after spending time with a number of impressive DFAT, DFID and Asia Foundation folks working on a range of different development programmes. In meeting after meeting, we heard about people ‘thinking and working politically’ (TWP) in all sorts of ways: finding innovative ways to better support women parliamentarians; thinking through implementation of the new ‘Village Law’, designed to bring more financial resources and control to the microlevel; better integrating health and education reforms to tackle HIV; harnessing youth engagement and social media to fight corruption.

Far from TWP being something that sits only with governance advisors, we found evidence of it everywhere we looked. But we also found some cynicism, a sense that TWP didn’t serve the needs of the people who were, ironically, doing it all the time (and, at least to our observations, doing it well). Three main reasons kept coming up in our conversations: 1) TWP (and now ‘Doing Development Differently’ – DDD) seems to be a bit ‘cult-ish’, with too many ‘Messiahs’ rocking up in Jakarta or elsewhere to tell people what they’re doing wrong and how, if only they’d listen, what they could do better; 2) a perceived lack of appreciation for how much the local political context shapes how much political space there actually is for external actors, in particular, to work differently; and 3) how much PEA there is sitting on people’s shelves or, worse, in their ‘circular file’, i.e., the bin.

So sitting there, enjoying satay (one of life’s true pleasures) and fruit juice (enough said…), we thought long and hard about what’s missing in PEA, why it matters and what we’ve learned and observed over the years. We came up with four gaps.

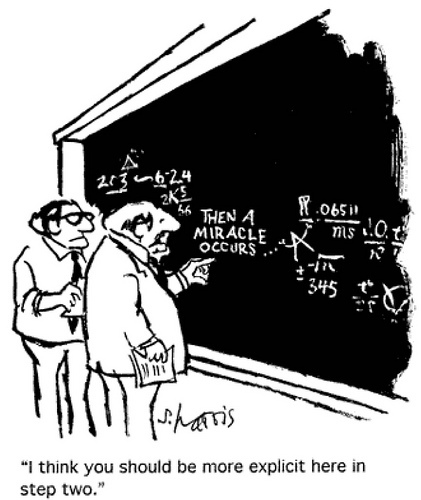

If only it was this easy

First, it’s time to stop thinking about politics in PEA through a single lens of institutional theory. Economists may like talking about interests and incentives, but it hides away the ‘real’ politics – the compromises, deals, coalition building, battles for power and so on – that lie at the heart of every country’s political system. And it’s a better way to engage with non-economists/governance types as well. Everyone inherently gets power, but not everyone gets ‘institutions’. At a recent TWP Community of Practice meeting in Bangkok, participants brought a gender lens to shine on TWP (and vice versa), showing how power needs to be at the heart to TWP. So why not put it at the heart of PEA? Can it help go some way towards keeping PEA in people’s heads, on their desks and out of the bin?

Second, the time to see PEA as a one-off discrete process that happens as part of initial programme design is at an end. Political analysis needs to be a living, breathing process that fits the operational needs of development practitioners. Political analysis need to be an everyday thing that helps people test their assumptions and theories of change as they go along. It needs to be used to help teams frame conversations about better learning from success and failure. It should be an essential input into strategies. Sure, a one-off PEA report written by an external expert will always have its place, but it should be one of a menu of choices (and not always the default one). There needs to be a rethink of PEA based on demand and need, not based on supply.

Third, we need to be able to answer the question, ‘But does PEA/TWP/DDD actually work to make development programmes more effective?’ Common sense says it should, and some single case studies suggest that it’s likely, but we have no ‘rigorous enough’ evidence base on PEA or on TWP/DDD. Something systematic and comparative, that doesn’t ‘cherry pick’ successes and then tells only part of the story. As we say in our paper, those of us in this ‘space’ make a lot of claims and demand a lot of changes without knowing for sure that we’re right, or even that we’re right in the right way. Just because something happened in the Philippines or in Nigeria in one way, will it work like that in another context? Because something worked in a particular way in a legal reform programme, will it work in a big infrastructure one? Anecdotes (should) only get us so far. What we have now are some fantastic attempts at theory generation and reflection (Sue Unsworth and David Booth’s paper is probably the best example of this so far), and a forthcoming DLP paper sets out a way to build on this work (and others) in order to build this much-needed evidence base. Some organisations are doing important internal reviews. Hopefully, with the collective effort of authors in the OECD book and beyond, we’ll soon have a more definitive answer to the ‘but does it work?’ question than we’ve had before.

Finally, we need to get more real about the things we can actually change and what we can’t. There’s good work out

there on why donors in particular struggle with TWP (though many lessons also apply to large INGOs and other bureaucracies). But the solutions suggested rarely seem politically feasible. Get rid of the imperative to spend? But that’s what government departments – all government departments – do. They’re given a budget and they spend it, and if they don’t, they lose it. Hire more political scientists or more ‘mavericks’? But what happens to existing staff with their strong technical knowledge in an era of austerity and cuts? Get rid of log frames? But how then do we hold programme leads to account? Focus on working more flexibly and adaptively? But how do we keep politics at the heart of this?

What our time in Jakarta (and elsewhere) showed us is that great people are finding ways to better think and work politically all the time, but they’re often doing it by swimming upstream. They’re not usually getting support from above, but they’re not really getting the support they need from PEA experts either. What they are doing is coming up with tweaks to normal business practice that make this a lot easier, and is politically easier in the often contentious contexts in which they work: co-designing programmes with both sector and governance staff; creating cross-sector strategies with on-going political analysis at the heart of regular team discussions; designing programmes with embedded, independent researchers so that political analysis is something that happens every day.

politically all the time, but they’re often doing it by swimming upstream. They’re not usually getting support from above, but they’re not really getting the support they need from PEA experts either. What they are doing is coming up with tweaks to normal business practice that make this a lot easier, and is politically easier in the often contentious contexts in which they work: co-designing programmes with both sector and governance staff; creating cross-sector strategies with on-going political analysis at the heart of regular team discussions; designing programmes with embedded, independent researchers so that political analysis is something that happens every day.

Our paper explores all of this in a bit more depth, but it also sits in a collection that aims to break down some of the walls between governance advisors and everyone else so that political analysis and TWP can become a better part of everyday working. It’s refreshingly critical (and self-critical) and is rooted in the day-to-day operational realities of development programming. We think that it shows how Lucy – or her real-life counterparts – are entering the field at an exciting time, but one where she needs to be open-minded and her colleagues need to be refreshingly honest about the challenges and the ways in which to better overcome these.

October 6, 2015

‘Thanks, but the truth is I hate being a refugee’: a young Syrian introduces Oxfam’s new briefing

The arrival of tens of thousands of Syrians at Europe’s borders in recent weeks has been a sharp reminder of the

Cousins Sahir 6, and Tariq, 4, from Deraa, in Zaatari refugee camp, Jordan

tragedy engulfing the people of Syria. Today, Oxfam publishes its latest briefing on the country’s continuing conflict. Dima Salam (not her real name), a young Syrian refugee now working for Oxfam in the UK, introduces the new paper.

Today Oxfam has published a fair shares analysis of the international community’s response to Syria. Oxfam is calling for donor countries to reverse the shortfall in funds for humanitarian relief and for countries to take in more refugees. This is important and exactly what I would hope Oxfam to be calling for, but let me tell you how it feels when it’s your country that is falling apart.

In December last year, I got promoted! Well, it’s not as exciting as it sounds. It’s not the type of promotion you hear about in normal life, but for me it was a life-changing one. I was an asylum seeker and, thankfully, I am now a refugee.

Some would argue that I am one of the luckiest refugees. To some extent, I agree. I flew to the UK to do my masters on a student visa like so many other young people around the world wanting to prosper and widen their choices. The idea of seeking asylum was not even on the radar. I came to the UK with the goal of making my family proud and returning home to share the success.

But while I was enjoying my UK student life, things were getting much worse back home. When I left Syria at the end of 2013, the country was in a dreadful situation – people were being killed, kidnapped and forced out of their homes. Yet, I wanted to go back. I hoped that things would get better.

As the situation for my family got worse, it made me keener to return. I wanted to be close to my parents and my brothers, to share their suffering. Being torn from one’s own family is hurtful as it is, but being far away and incapable of offering any help is the worst kind of suffering. My father had a different view: “if you want to help, stay there and be safe”. Really dad? On my own? A refugee and on my own?

I’ve always been fond of Britain and always wished to live here, albeit for a short time. I’ve always believed that this country has a lot to offer. And now, I have it all. I have everything I’ve been dreaming of and a bit more. The only thing I hadn’t foreseen is that I would have all of that, and not be happy about it.

Yes, I am grateful for what I’ve been given. Life is so much nicer here. Everything you’d think I would want is at the tips of my fingers: food, clothes, and a safe home to return to at night. I do have a better life, much better than it could ever have been in Syria right now.

The Damascene Sword, symbolising Syria’s cultural and historical heritage, painted by a friend of the author to portray peace, serenity and a hope of return.

So many factors have helped me to be here – obviously the British government’s generosity in granting me asylum. But the truth is I hate being a refugee. I hate the feeling that I didn’t really choose to be here. That’s why I try my best to avoid showing anyone my documents stamped with the word “refugee” as my status in this country.

I feel selfish for not appreciating what I have, and I urgently call for more to be done for other refugees: Help Syrians! Bring more asylum seekers to Europe! Provide better lives for them!

But sometimes I pause, and think: what if they hate being refugees too? I am sure they do but they’re like me, they don’t have the luxury of choice. They just want to live.

As a refugee, every day I see the compassion of ordinary people that I meet. I really hope for this compassion to be translated into more action that their governments might take. I hope Europe will offer refuge to more people. But I know painfully well that the violence and bloodshed inside my own country must come to an end, and that the world could unite more to help bring that about. If action doesn’t happen now, in this critical moment, it never will. And those people fleeing Syria will become dusty pieces of a forgotten past.

The world should take the difficult but necessary steps to end the war. It has to stop contributing to killing and displacing the Syrian people. An obvious step towards achieving this is for the world to stop supporting the entry of any arms to Syria – be it for the regime, for the opposition, or for any of the many other groups. Only then will all factions find themselves willing to sit together, listen to each other and negotiate solutions.

Put more simply, when the world intends to value the lives and souls of Syrian humans more than it values the endless foreign interests in the Syrian civil war, only then will Syrians stop becoming victims of killing, false imprisonment, hunger, destruction, and displacement.

I would like to use this space to thank the UK for what it has given me and what it is still giving me. I am grateful for being able to think out loud and praise and criticise – something I couldn’t do back home. I want to thank the UK for its £1 billion in aid for Syrian refugees, for the Syrian refugees it has accepted and for the 20,000 more it has pledged to resettle.

The importance of all that cannot be underestimated. However, the UK and the world must not lose sight of the root problem that is pushing people to flee their country – and of course not forgetting those who remain behind. There is a grave, urgent task for the whole world to come together as a united front and look at things through the same lens: the lens that shows the simple reality of human beings wanting to live a decent life without war, and without being forced to flee their homes.

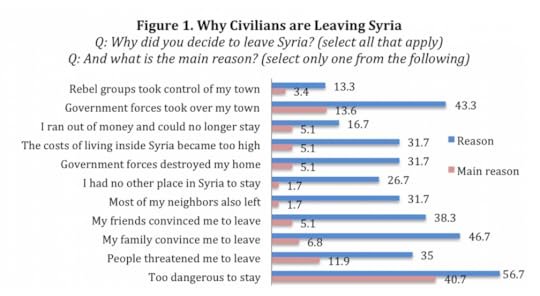

More reflections from Maya Mailer on the launch here, and here’s a table on from the Fair Shares paper – an awful lot of red. Overall the Syria response has less than half the money needed ($8.9bn)

October 5, 2015

Where has the global movement against inequality got to, and what happens next?

Katy Wright, Oxfam’s

Head of Global External Affairs, stands back and assesses its campaign on inequality.

The most frequent of the Frequently Asked Questions I’ve heard in response to Even it Up, Oxfam’s inequality campaign. is “how equal do you think we should be?”

It’s an interesting response to the news that just 80 people now own the same wealth as half the world’s population put together, and the best answer was that given by Joe Stiglitz to a group of UN ambassadors: “I think we have a way to go before we worry about that.”

So how far do we have to go, exactly? The good news is that inequality is no longer just the concern of a small number of economists, trades unions and social justice campaigners. It’s now on the agenda for the international elite.

That partly reflects a growing realisation that inequality may be a problem for us all, not just those at the bottom. The Spirit Level raised questions about the impact of inequality on societies, and the rise of Occupy pointed to a growing political concern.

That partly reflects a growing realisation that inequality may be a problem for us all, not just those at the bottom. The Spirit Level raised questions about the impact of inequality on societies, and the rise of Occupy pointed to a growing political concern.

More recently, research papers from the IMF have demonstrated extreme inequality is at odds with stable economic growth, and that redistribution is not bad for growth. Significantly, this shift in focus from the IMF has been driven by Christine Lagarde. To the outside world, the IMF now officially cares about inequality, as do Andy Haldane at the Bank of England, Donald Kaberuka (outgoing head of the African Development Bank), and Alicia Barcena of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, to name a few.

The World Economic Forum too has repeatedly warned of inequality as a major global risk (as well as providing, through its Davos meetings, the perfect backdrop to Oxfam’s much-publicised ‘killer facts’).

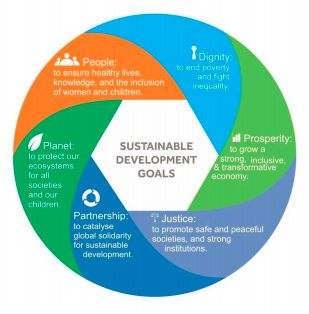

Finally, the inclusion of an inequality goal in the new Sustainable Development Goals indicates a willingness to see

inequality reduction as an explicit policy aim of government. I remember being told in early 2013 by a UK Government adviser that Oxfam’s very use of the word inequality in a headline was “very unhelpful”. Two years later and that government is ready to champion a new set of global goals with reducing inequality in at goal number 10 (no irony intended).

So far, so useful: for NGO campaigners, allies don’t come more unusual than these establishment voices.

But we now face three challenges:

First is the basic one: how to ensure that institutions that have started to talk about inequality turn this into action? A second and more difficult challenge will be to force through reforms that go further than institutions intended, and involve going up against vested interests.

And the third challenge is perhaps Oxfam’s greatest: How to ensure that this concern for inequality actually benefits

credit: Paul Smith, Panos

poor people? Interestingly recently it’s the IMF that appears more worried about extreme income inequality – because of the impact on economic stability – than the World Bank, which has been more cautious, despite its poverty mandate. If the actors we are relying on for change are primarily motivated by concern for GDP, for political stability, and to preserve what works for them, we will need to work to ensure that responses to inequality are not delivered solely on the terms of those at the top, in order to keep those in the middle happy.

So what opportunities exist that we can use?

Where we’ve seen progress, we should keep pushing: Tax dodging is now a regular agenda item at global summits, but so far efforts have tended to be in response to the needs of developed countries. The current mandate for tax system reform is with the OECD, but even before its action-plan on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting has been published, tax campaigners see it as a plan drawn up by rich countries that won’t help poorer countries keep corporate profits onshore.

Now the IMF and World Bank are looking to deepen their dialogue with developing countries on tax issues and to strengthen the voice of developing countries in the international debate on tax. In addition, the Financing for Development Summit in Addis saw G77 countries being more outspoken in their demands to have a say in global tax rules. With these dynamics enabling us to keep tax on the agenda and to widen the scope of institutions involved, a broader redesign of the global tax system could be on the cards.

We shouldn’t be fixated on governments as targets: Many people’s daily experience of inequality is not as voters; it’s as workers or customers or small business owners. Oxfam’s Behind the Brands campaign has shown how swiftly even big multinational companies will respond to pressure on their public image, in comparison to the sluggish response of governments. Companies paying outlandish pay ratios, investors who can influence corporate behaviour, or individuals using anonymous shell companies, all could be targets.

Neither is it necessarily the case that such victories would be at the expense of more systemic change. The campaign to get organisations to divest from fossil fuels has allowed local, easily replicable campaigns to force change across a range of institutions, creating a domino effect of small victories and indirectly increasing the pressure on government policy to move away from fossil fuels.

Brazil

Stopping bad things happening may be just as important: When it comes to challenging what is broadly known as the privatisation of aid (use of Public-Private Partnerships – PPPs, financial intermediaries, blended finance etc) it’s useful to share a common language of concern for inequality with those you’re trying to influence.

But that argument must be joined with evidence and politics to ensure change: We’ve seen success in recent years in creating national political fights over attempts to introduce user fees for healthcare, and in using investigative efforts to highlight the dangers of PPPs for ensuring public services reach the poorest people.

There’s opportunity here for institutional change too: Jim Kim at the World Bank is progressive on the issue of removing user fees on healthcare, and promoting free healthcare should be part of his legacy issue within the Bank.

Of course, added to these suggestions would be a wealth of other opportunities to push change with national governments – spotting and using political opportunities to do so.

Oxfam has played a small part in drawing attention to the inequality crisis, and in influencing the right people to be concerned. Achieving change will mean a lot more than just repeatedly calling for ‘rhetoric to turn into reality’ or Duncan’s bugbear, ‘political will’. Removing the ideological barriers is important, but the decisions of those in power are rarely made purely on policy considerations. Policy change on this scale needs a combination of ideas, public and peer pressure, leadership, and events, accidents and plain good luck. The role of activists is to keep a careful eye on what’s going on, build alliances and seize opportunities when they arise.

October 4, 2015

Links I Liked

Why people are fleeing Syria – fear of Assad government is given four times more often than fear of opponents.

New Hunger and Nutrition Commitment Index ranks governments on their political commitment to tackling hunger and undernutrition

Women in Bangladesh are taking charge – from grassroots up to government. Good overview on women’s rights, education, politics

Going to use this Dilbert argument in my next performance review. What are  my chances?

my chances?

NGOs in Malawi: What happens when donors leave? Important sustainability & partnership issues here

The best way to kill an idea, [h/t Calestous Juma]

“If you’re tired, we can walk amok.” Top 10 Words Used With Only One Other Word [h/t Charlie Beckett]

African solutions to African problems? The end of the Burkina coup may spell a different regional leadership role for ECOWAS [h/t RachelStrom]

Is it just me, or is this Richard Curtis film for the Global Goals/SDGs (what are we supposed to call them these days?) not up to the standard of some of his previous work? (and not just because a list of goals aren’t actually a plan, unless they have some kind of theory of change – did I mention that before?)

October 1, 2015

ICYMI: This summer’s posts on theories of change, systems thinking and innovation

Still dripfeeding in catch-ups on the most popular posts from June-September, when the blog’s email alert system collapsed and some wasters actually went on holiday. There were some good discussions and lots of traffic on how change happens, which bodes well for future book sales. The most read was actually a 2013 post on Theories of Change, but this one, from Oxfam’s James Whitehead, came a close second:

‘Is it innovative?’ ‘How can we be more innovative?’ When asked, my problem, which is slightly awkward as Oxfam’s  Global Innovation Advisor, is that I’m not sure how useful the word ‘innovation’ really is. I’ve just written a research paper on the factors that enable or block innovation in Oxfam and one of the things that comes out is that those who are ‘innovators’ don’t see themselves as such and don’t label what they do as ‘innovation’. They just get on with working with others to solve problems.

Global Innovation Advisor, is that I’m not sure how useful the word ‘innovation’ really is. I’ve just written a research paper on the factors that enable or block innovation in Oxfam and one of the things that comes out is that those who are ‘innovators’ don’t see themselves as such and don’t label what they do as ‘innovation’. They just get on with working with others to solve problems.

Duncan may characterize it as an unwieldy supertanker, but Oxfam actually has a pretty good track record on innovation, stretching back to its earliest days. In the 50’s and 60’s it pioneered charity shops and humanitarian response. In the 1970’s it developed water tanks for emergencies and ‘magic stones’ terracing to reduce desertification in the Sahel that are both still in use today. The 1980’s saw the invention of energy biscuits with Oxford Brookes University and one of the first consortia on HIV/AIDS. In the 1990’s it launched the first Fair Trade Foundation and even got a nomination for the Nobel Peace Prize. In the 2000’s it played a pivotal role in the ‘Make Poverty History’ campaign and developed new approaches to fundraising like ‘Oxfam Unwrapped’ presents that have now raised more than £50 million. In this decade, we injected new energy into the campaign for an international Tobin Tax and helped secure a global Arms Trade Treaty. But the crucial point is that none of this happened because we were consciously trying to be innovative.

So if I’m looking to be ‘more innovative’ maybe I’m looking in the wrong place. Innovation is a by-product of the process of collaborative problem-solving – it’s not the destination. As a development community we are trying to address complex problems in a changing world – the response may be a proven approach developed thirty years ago or something unprecedented. I want to be working with people who are passionate about solving problems at scale rather than magpies obsessed with finding shiny new innovative solutions.

So if I’m looking to be ‘more innovative’ maybe I’m looking in the wrong place. Innovation is a by-product of the process of collaborative problem-solving – it’s not the destination. As a development community we are trying to address complex problems in a changing world – the response may be a proven approach developed thirty years ago or something unprecedented. I want to be working with people who are passionate about solving problems at scale rather than magpies obsessed with finding shiny new innovative solutions.

I also find that if I ask my colleagues across the organisation to identify work that is innovative I will often be met with a blank look, a pilot with little room for growth, or of course an app. If I ask where our work is exciting and has potential to make a massive difference for people, that’s when the lights come on and the conversation gets interesting.

But, and it’s quite a big but, we are usually not nearly creative enough, not nearly collaborative enough in addressing these complex problems. And that does people in poverty a monstrous disservice. Have you ever been to a health centre and seen a poster pinned up on a wall, with a cartoon of a man beating a woman with a stick and a UN logo and INGO logo proudly on the bottom of it, announcing that you should ‘say no to violence against women’? Where is the resourcefulness and ingenuity in that? Is that honestly the best we could come up with? In contrast, I was excited spending time with our Zambia country team earlier this month when they told me they are working with a major brewery to get messages onto beer mats about violence against women. Is it innovation? I don’t know. But it is most certainly a more resourceful approach.

So what enables or blocks this sort of creative problem-solving? In the research paper we found that it starts with  recognising, nurturing and retaining talent. Those who drive the change are the ones who consistently go beyond the call of duty. They are open to opportunities and challenges in their context, creative in their responses and delivery focussed. But frequently those staff face a chronic lack of time as they are busy delivering existing obligations. One staff member said “In the early stage this wasn’t core work – it was done at weekends and nights because we didn’t have funding.” And yet these initiatives might become the cornerstone of our future programmes.

recognising, nurturing and retaining talent. Those who drive the change are the ones who consistently go beyond the call of duty. They are open to opportunities and challenges in their context, creative in their responses and delivery focussed. But frequently those staff face a chronic lack of time as they are busy delivering existing obligations. One staff member said “In the early stage this wasn’t core work – it was done at weekends and nights because we didn’t have funding.” And yet these initiatives might become the cornerstone of our future programmes.

There are leaders at every level who keep open the space, act as champions, find resources, encourage teams to take risks and defend them when things get difficult or don’t deliver. One respondent said about her manager “She would say – just go and do it, I believe in you. I knew even if I failed, she would be there to support me.” That sort of leader.

Another critical element is vibrant collaboration and partnerships. While working with diverse stakeholders takes time and effort, we found it pays dividends when we involve the right people and are prepared to develop solutions together. Flexible funding in the early stages, through proactive relationships with donors, also made a difference. So did a hunger for learning – the desire to know what’s working, what’s not and to fail fast, learn and adapt.

In order to be more resourceful problem solvers, we need to become highly collaborative across disciplines, less hierarchical, highly connected, open to experimentation and learning, open to considered risk-taking, very outward facing and get better at working with other organisations. Innovation is not the destination, it will occur as a by-product of our combined efforts.

In order to be more resourceful problem solvers, we need to become highly collaborative across disciplines, less hierarchical, highly connected, open to experimentation and learning, open to considered risk-taking, very outward facing and get better at working with other organisations. Innovation is not the destination, it will occur as a by-product of our combined efforts.

Other summer posts on theories of change, systems etc:

DFID and NGOs shifting to adaptive development

Is it useful/right to see Development as a Collective Action Problem?

Development 2.0, the Gift of Doubt and the Mapping of Difference: Welcome to the Future

What are the key principles behind a theory of change approach? Top new ODI paper

September 30, 2015

Is the International Humanitarian System hitting a tipping point on ‘going local’?

Marc Cohen, Senior Researcher at Oxfam America, is excited about the new World Disasters Report

Over the past two years, a boatload of reports and studies has pointed to the need to shift to greater local leadership of disaster prevention, preparedness, and response. In part this is driven by mounting humanitarian needs and the growing gap between those needs and the aid actually provided. There is also a related concern with the effectiveness of humanitarian action in an era of scarce resources. And for some, it is a matter of rights and justice, embodied in the principle of subsidiarity.

A number of national and international humanitarian agencies have pressed for greater attention to strengthening local capacity and working with local humanitarian actors on all phases of humanitarian action. This has led to such reports as the ‘Missed Opportunities’ series on the importance of humanitarian partnerships with local actors, and ‘Funding at the Sharp End’, looking at the resources that international humanitarian NGOs transfer to local partners. Further, the Charter for Change has been developed – this seeks tangible commitments from INGOs on localisation, to be achieved by 2018.

For its part, Oxfam has recently argued that ‘shifting the centre of preparedness and response to the national and local level puts responsibility, decision making, and power where it should be: in the hands of the people affected most by crisis’. Of course, we look at this through the lens of effective states and active citizens, in keeping with our rights-based approach and the approach of this blog. We’ve tried to put our money where our mouth is on this issue. Over the past decade, we’ve received multiple grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for emergency response and disaster risk reduction efforts, including capacity-strengthening of partners, in Central America. One of those partners is the Concertación Regional de Gestión de Riesgos (CRGR), a four-country regional organization aimed at increasing the capacity of vulnerable communities to prepare for and respond to disasters. In a demonstration of our commitment and that of our partners to effective capacity strengthening, in 2012, the Gates Foundation awarded $1.6 million directly to CRGR.

For its part, Oxfam has recently argued that ‘shifting the centre of preparedness and response to the national and local level puts responsibility, decision making, and power where it should be: in the hands of the people affected most by crisis’. Of course, we look at this through the lens of effective states and active citizens, in keeping with our rights-based approach and the approach of this blog. We’ve tried to put our money where our mouth is on this issue. Over the past decade, we’ve received multiple grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for emergency response and disaster risk reduction efforts, including capacity-strengthening of partners, in Central America. One of those partners is the Concertación Regional de Gestión de Riesgos (CRGR), a four-country regional organization aimed at increasing the capacity of vulnerable communities to prepare for and respond to disasters. In a demonstration of our commitment and that of our partners to effective capacity strengthening, in 2012, the Gates Foundation awarded $1.6 million directly to CRGR.

Now the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) – the world’s largest humanitarian network – has joined this debate. Through its 189 National Societies and the efforts of its 17 million volunteers who work through local chapters, the Federation reaches 150 million people worldwide. This year, IFRC is devoting its widely read World Disasters Report to the topic of local humanitarian actors, whom it characterises as ‘the key to humanitarian effectiveness.’

Federation Secretary-General Elhadj As Sy emphasises in his foreword to the report that calling for greater  international recognition of, and support for local humanitarian actors does not mean that there is no longer a role for international actors: ‘ The international community still has a very important role to play, but a better balance needs to be struck. International actors can provide specialized resources and technical expertise, brought with humility, trust and respect, and with a true commitment to building local capacity.’

international recognition of, and support for local humanitarian actors does not mean that there is no longer a role for international actors: ‘ The international community still has a very important role to play, but a better balance needs to be struck. International actors can provide specialized resources and technical expertise, brought with humility, trust and respect, and with a true commitment to building local capacity.’

Likewise, Dr Jemilah Mahmood, the Head of the Secretariat of the World Humanitarian Summit—which will take place in May 2016 in Istanbul—has noted that one of the strongest calls from the global consultations that have taken place in the run-up to the Summit has been for ‘countries, communities and local organizations, including the private sector, to manage natural disaster risk and response by themselves, building on their own knowledge and expertise’.

So, do we have consensus that localisation should top the humanitarian effectiveness agenda? Hardly.

In mid-September at the International Conference: A Quest for Humanitarian Effectiveness?, held in Manchester, UK, there was a lively debate on localisation. Proponents argued that local leadership is faster, cheaper, and helps more people than big, clunky, internationally-led responses. They pointed to the example of Bangladesh, which experiences far fewer deaths when cyclones hit thanks to substantial investments in early warning, better storm shelters, and disaster management bodies from the community to the national level. Critics wondered whether local actors can deliver health, water, and sanitation services needed in large-scale emergencies, and how local leadership works in situations of armed conflict when the government is implicated in the violence and has suppressed civil society.

This debate will go on, well beyond the Summit in Istanbul. But it is heartening that a big international humanitarian actor such as the IFRC has joined in the fray on the side of strengthening local actors so that they can take the lead.

[also worth reading: the The State of the Humanitarian System report, published today by ALNAP, echoes these conclusions, among others]

September 29, 2015

Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities use 65% of the World’s land; how much do they actually own?

Andy White, the Coordinator of the Rights and Research Initiative (RRI) introduces a new report.

A new, unprecedented legal analysis has revealed that despite using and inhabiting up to 65% of the world’s land, Indigenous Peoples and local communities—a population of about 1.5 billion—possess legal rights to barely 18%.

That’s a huge gap. And it’s a gap that explains a lot of widespread disenfranchisement, poverty, and conflict across the world. The right to land and natural resources is not just a basic human right, it is also linked to many key development indicators—from food security, poverty eradication, and gender equality to combating climate change, deforestation, and displacement.

For indigenous and local communities, the relationship to land is a vital component of culture as well as survival. When that relationship is trampled, the resulting disenfranchisement can become a gateway to social, often violent conflict.

It is no surprise then that according to the study, almost 100% of land in 10 out of 12 countries listed as fragile states by the World Bank is owned by the government or private sector, and not the people who have actually lived there for generations. In fact, disputes over land and natural resources are a major contributing cause of armed conflict across the world.

The study, conducted by the Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI), gives us for the first time an international baseline of the amount of land that’s legally recognized as owned or administered by Indigenous Peoples and communities. It identifies the land area in 64 countries (over 80% of the world’s total land surface) that’s formally recognized under national laws as owned or controlled by Indigenous Peoples and local communities. It covers drylands, grasslands, forests, and most other rural areas.

This study also establishes a baseline of country performance on legal recognition—finding for example that more than half of all of the countries studied have no legal avenue whatsoever to enable recognition. It also identifies the countries that do have such court rulings or laws, but have yet to implement them. Ultimately, it shows us where we have solid potential for progress, and hands us a tool with which to measure it.

An Indonesia Constitutional Court ruling in 2013, for example, invalidated government control of the country’s customary forests. If and when this ruling is implemented, it could increase the amount of land owned or controlled by Indigenous Peoples and local communities from 0.25 percent of the national territory to approximately 23 percent—a real game-changer for millions of Indonesians.

Good for people; good for the planet

Past research comparing the impact of strong land rights on the health of rural lands and natural resources has found that Indigenous Peoples and local communities conserve the nature of their territories best, keeping the carbon in the trees and ground and thus slowing climate change.

that Indigenous Peoples and local communities conserve the nature of their territories best, keeping the carbon in the trees and ground and thus slowing climate change.

For instance, indigenous reserves in the Brazilian Amazon have played a critical role in lowering national deforestation rates, and increased forest rights for farmers in Niger have added 200 million new trees over the past 20 years, storing an additional 30 million tonnes of carbon.

Here’s why that matters: Indigenous Peoples and local communities today have legal or official rights to at least 513 million hectares of forests, about 1/8th of the world’s total forest and around half of the forests they actively use or claim. Collectively, this area contains approximately 37.7 billion tonnes of carbon—29 times more than the annual emissions of the world’s passenger vehicles! Recognizing and securing local peoples’ rights to the remainder of their forests is an essential strategy to reduce deforestation and climate change.

Unfortunately, efforts to monetize and trade the carbon found in these forests on the open market has given national governments yet another reason to seize control from the local residents—even though those residents have kept the forests standing since before most governments even came into the picture.

A trigger for renewed efforts?

Here’s that potential for progress that gives us hope. Several countries in the survey have laws that could dramatically expand legal recognition for Indigenous Peoples/local communities if they were implemented in letter and spirit. One great example is India.

Here’s that potential for progress that gives us hope. Several countries in the survey have laws that could dramatically expand legal recognition for Indigenous Peoples/local communities if they were implemented in letter and spirit. One great example is India.

In India, we found that a landmark forest legislation Act passed in 2006 obligates the state to recognize the rights of approximately 150 million forest dwellers on at least 40 million hectares of forested land. We also saw that the districts with the largest eligibility for land rights recognition also contain the country’s poorest areas, signaling huge potential for economic progress. They are also the districts with the maximum number of land-based social conflicts.

So while implementation of India’s Forest Rights Act has been stalled for almost a decade, this year, the current government rejuvenated efforts to address the issue. As promising as this is, it remains to be seen if the government will fight off competing private sector interests and its own economic ambitions to keep up those efforts.

In fact, over the past two years, there have been numerous commitments from both governments and the private sector, from the New York Declaration on Forests to the Liberian and Indonesian governments’ pledges to recognize their local peoples’ rights. But so far, these remain promises. While the intent is laudable, the reality is that Indigenous Peoples and local communities in far too many countries still lack participation and ownership in decisions affecting their land, resources, and livelihoods.

Fortunately, there are now new tools and mechanisms in place, as well as a global call to action for all key actors to scale-up efforts on these commitments. We also have lessons to learn from countries that have implemented good land rights legislation and reaped benefits. It’s time to shift from rhetoric to action, and that’s what the upcoming international conference on community land and resource rights, where this study is being released, hopes to achieve.

The study is being released today at a conference in Bern, Switzerland, co-organized by RRI, the International Land Coalition (ILC), Oxfam, and Helvetas Swiss Intercooperation.

September 28, 2015

Hello SDGs, what’s your theory of change?

As Jed Bartlett would say, what’s next? Now the SDGs are official, there will be big discussions on financing and a  geekfest on metrics and indicators. Both are important. But to my mind the big task is to collectively think through what the SDGs are meant to change and how they can best do so – in other words a theory(ies) of change. Here are some initial thoughts:

geekfest on metrics and indicators. Both are important. But to my mind the big task is to collectively think through what the SDGs are meant to change and how they can best do so – in other words a theory(ies) of change. Here are some initial thoughts:

Targets: Who/what are the SDGs supposed to influence? There are at least four:

Developing country budgets and policies

Wider social norms about rights and the duties of governments and others

Aid volumes and priorities (i.e. a re-run of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which were mainly effective as an aid lobbying tool)

Developed country budgets and policies

Of these I think the first two are the most promising: aid is falling as a percentage of government revenue, while I do not think the SDGs are likely to have much influence on the policies of developed countries (hope I’m wrong of course).

Channels: for each of these, we need to think through how the SDGs could exert real traction. In the case of developing country budgets and policies, this could be through

Peer pressure – already in New York, some ‘vanguard governments’ (Colombia, Gabon, Indonesia) were taking about internalising the SDGs in domestic processes. They could be effective sources of pressure on their neighbours and others to follow suit. What kind of platform or reporting process could help them do so?

National media: always a good source of pressure on decision makers. What sort of data and media operation around the SDGs is likely to grab their interest at regular intervals over the next 15 years?

Civil Society: what do national CSOs need in order to make the SDGs an effective part of their advocacy repertoire?

Private Sector: how can the SDGs be relevant to progressive national and international companies and their business associations, so that they become part of the dialogue between them and government, or influence their operations directly?

Dynamics: Will SDGs have a steady drip-drip effect, or will their main impact be around ‘critical junctures’, such as scandals, crises or changes of political leadership? What does that imply for the design of the SDG system, eg if critical junctures are important, what kind of rapid response is needed so that researchers or advocates can respond quickly with a timely summary of the case for change? If, however, the SDGs are most likely to be effective via long term osmosis eg on social norms around inequality and exclusion, a different reporting and follow up process is likely to be preferable.

Dynamics: Will SDGs have a steady drip-drip effect, or will their main impact be around ‘critical junctures’, such as scandals, crises or changes of political leadership? What does that imply for the design of the SDG system, eg if critical junctures are important, what kind of rapid response is needed so that researchers or advocates can respond quickly with a timely summary of the case for change? If, however, the SDGs are most likely to be effective via long term osmosis eg on social norms around inequality and exclusion, a different reporting and follow up process is likely to be preferable.

Complexity: According to ODI’s Claire Melamed ‘there won’t be one way the SDGs affect outcomes, there will be loads, and most are unpredictable at this point. For some governments, it will be comparison with others (so league tables) for others it will be domestic pressure (so whether SDGs are useful for domestic campaigners) for others more of a management tool. All are likely, and which it is will change with country/administration (and most countries will have several governments over the next 15 years) and goal (governments are likely to treat education differently to climate change, for example). As Craig Valters argues, that means taking a theory of change approach, rather than trying to settle on a single ToC for the whole SDG system. We could of course say ‘we have no idea how this will all pan out, so let’s just let a thousand flowers bloom and not bother with ToCs.’ But the system does have to agree on a bunch of procedures on monitoring, reporting, follow up etc, so it would surely help to make sure these procedures recognize and work with the messiness of how the SDGs are likely to be used in practice.

Review: For example, let’s assume that whatever initial conclusions those designing the SDG system arrive at are at best only partly right. How/when will everyone sit down, review what has/hasn’t worked, and make the necessary adjustments?

Where to start in answering these questions?

It would have been better to have had this discussion from the beginning of the process (as I said in this 2012 paper), but it hasn’t happened. Never mind. If people are serious about the SDGs having impact, I think some quick and smart research is required along at least two lines:

First we need a good literature review: what can we learn from the hundreds of international instruments that seek

If I could photoshop, this would read ‘SDGs agreed’ on the left and ‘world a better place’ on the right…..

to influence governments, change norms etc: 190 ILO Conventions, dozens of UN Conventions, the WTO, Regional Trade Agreements, Bilateral Investment Treaties etc. Which of them have gained traction on governments or norms, and how? See May-Miller Dawkins’ excellent ODI paper on what the SDG crew can learn from other international agreements.

Second, can someone finally go out and do some decent research with developing country decision makers? By that I mean well designed interviews (no leading questions, please!) to find out what international instruments actually influence them, how and why. As a start, the ODI (what would we do without them?) has an excellent study by Moizza Sarwar coming out in the next week or so, exploring the implementation of the MDGs by interviewing senior planning ministry staff in five developing countries. (What took them so long?!)

Why would this help?

Armed with this kind of analysis, people in different contexts (UN, bilateral, national, civil society) would be better placed to think through how to implement the SDGs just agreed in New York. For example:

How should target institutions like developing country governments be involved in the governance of the SDGs?

Should reporting be national, regional or global? By governments only, with non-government inputs, or with right to reply from other bodies?

Would annual league tables make sense?

What is the best trade off between countries adapting the SDGs to their local context, and having global or regional comparability?

Who are the best messengers to report back on SDG performance (ex presidents? Nobel prize winners? Fading pop stars?)

What do you think? A futile attempt to impose order on chaos, or a useful exercise?

September 27, 2015

Links I Liked

Dilbert does the World Bank (h/t Makarand)

Interesting stuff on Ebola

Fascinating example of positive deviance. Why were 284 villages with community-led total sanitation Ebola-free, despite being close to the centre of the outbreak?

How West African governments fought the epidemic. Report from the Africa Governance Initiative reinforces Doing Development Differently on national systems and PDIA (Problem-Driven Iterative Adaptation)

Gender Inequality

Tackling the gender gap could add $12 trillion to the world economy, according to a new study (= GDP of Germany + UK + Japan)

And if you’re in London this Friday, come along to the LSE for Gender inequalities: policy and practice perspectives, joint Oxfam/LSE public event, 2 Oct, 6.30.

Is booze a development issue? 12 Sub Saharan African nations are among the 20 countries losing the most healthy years to alcohol use

Chris Blattman loves Cash Transfers:

Reflections on what he learned on the CTs panel – what evidence persuades, CT tipping points etc

Is handing out $50k at a time in Nigeria (mega CTs?) the most effective development program in history? Shameless clickbait.

10 photographers try and capture global inequality. Great series

10 photographers try and capture global inequality. Great series

September 24, 2015

Who is the richest man in history? The answer (ICYMI) might surprise you

3rd in this series of re-posts of the most read FP2P pieces over the summer comes from Ricardo Fuentes, who has

One of these men is Carlos Slim

since

gone off to be big boss at Oxfam Mexico.

Here he introduces Oxfam Mexico’s new report on one of Mexico’s many claims to fame – the richest man in history.

In his 2011 book, The Haves and The Have Nots, Branko Milanovic asked a simple but quite illuminating question: who is the richest man in history? (Given the gender structures and distribution of wealth and resources across men and women, it had to be a man). To simplify comparisons across time and space, he used a common metric for wealth: the number of people that a rich person could hire in his society with a conservative return on his wealth. Milanovic was following the thinking of Adam Smith, who wrote in The Wealth of Nations “[A

person] must be rich or poor according to the quantity of labour which he can command.”

Milanovic found that the richest man in history was the Mexican Carlos Slim, who at the time of the calculation could hire 440,000 Mexicans with his income (not with his wealth). That’s a huge amount of people. By comparison, John Rockefeller could hire about 116,000 during the Gilded Era. Bill Gates could only hire a paltry 75,000 workers at the peak of his wealth.

How has that changed since the publication of Milanovic’s book?

Gerardo Esquivel, a Mexican economist, did a similar calculation for an Oxfam Mexico report launched yesterday in Mexico City. The methodology is slightly different in Esquivel’s calculations. But see how it’s changed in ten years. In 2004, Carlos Slim could hire half a million Mexicans. Ten years later, he could hire 2 million (or about the number of officially unemployed people in the country). And just to be clear, this analogy does not try to vilify Carlos Slim but to highlight a skewed system that allows this enormous disparities.

The report has lots of new findings. Another interesting one: using tax records to calculate the share of income going to the richest 1% (as Piketty and other have done in several countries) Esquivel finds that the top 1% in Mexico take 21% of total income. That’s the highest share for all the countries with available information.

Mexico is a vastly unequal country in a vastly unequal region (despite some recent progress) so there is no real surprise there. The shock is just how fast the wealth at the very top continues to grow while salaries stagnate and the economy tumbles with skeletal per capita growth rates. In other words, the Mexican economy is not working for anybody except a privileged few. For instance, in 1996, the wealth of the 16 billionaires was $25.6 billion dollars. Today, the same group controls $142.9 billion dollars. In the same period, poverty has remained stubbornly constant – in its broadest definition, the poverty rate in Mexico has been hovering around 50% for the last two decades. There is wealth creation in Mexico, but it’s going into a small number of hands. Mexico is experiencing a sort of trickle-up economics.

The report argues that, this is the consequence of different failures in public policy in Mexico. On tax policy:

The report argues that, this is the consequence of different failures in public policy in Mexico. On tax policy:

“One of the big problems is that our tax policy favours those who have more. It is in no way progressive and the redistributive effect is almost non-existent. By taxing consumption—over and above income—poor families end up paying more taxes than the rich, since they spend a higher percentage of their income. The marginal income tax rate—one of the lowest among OECD countries—the fact capital gain in stock markets is not taxed and neither is inheritance, among other things, are examples of how the tax system benefits more privileged sectors”

There is also a close relationship between wealth and political influence that skews the system in the favour of the affluent. On this, the report says:

“The constant inequality and political capture by elites have serious economic and social consequences that are

Mexico City

also exclusionary. The internal market is frankly weak. When facing the scarcity of resources, human capital is curtailed and the productivity of small businesses is jeopardised.”

Mexico is a good example of the failure of trickle-down economics, just as the IMF also highlighted last week: per capita growth rates have been low but positive, between 1992 and 2012 they averaged 1.17%, but official poverty rates are back to where they were in the early 1990s.

So there is a huge task ahead to ensure that the economic and political system in Mexico delivers for Mexicans. The report suggest some initial steps: a genuine social state; a more progressive fiscal policy, improved targeting of expenditures, better wage and labour policies and enhanced transparency and accountability mechanisms.

There is nothing radically new in the proposals. What’s new is to have these conversations in a country with a long history of socioeconomic inequities. Wealth creation is necessary if the poor, vulnerable and marginalized are to improve their lot, but wealth creation that goes only to a few billionaires is unacceptable.

Buena Suerte with sorting that lot out, Ricardo. Will you be approaching Carlos for funding?

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers