Duncan Green's Blog, page 149

January 17, 2016

Links I Liked (and videos I valued)

Today is ‘Blue Monday’, supposedly the most miserable day of the year (actually just something dreamt up in 2005 by a holiday firm as a marketing ploy). But in any case, allow me to make it even worse with this truly awful video [h/t or possibly eternal damnation to Tim Aldred for sending it]. ‘We love the SDGs’. Take it away. Please.

In the ensuing twitter traffic, Katy Wright sent over another pretty terrible one on the Financial Transactions Tax. Any other candidates for impenetrable wonky issues set to really bad music?

Some other links I liked:

Some optimism for breakfast? 10 country case studies of progress in development on poverty, jobs, health, education etc from the ODI

Ensuring ‘quality of death’. What could other countries (including rich ones) learn from Kerala’s palliative care system?

The rise of political science blogging, aka the Monkey Cage, taking on the dominant econ tribes. But where’s the UK equivalent?

And continuing the theme of video nasties. Here’s Donald Trump’s Phoenix fan club (the lyrics are truly horrendous) [h/t Jay Rayner]

But here’s some redemption – a really uplifting Aussie university ad [h/t Chris Blattman]

January 10, 2016

Links I Liked

Hi there, been tweeting the odd link when I should be rewriting the book. Here’s last week’s highlights. And if Mark  Fried is reading this, here’s what a really tough editor is like.

Fried is reading this, here’s what a really tough editor is like.

Feeling a bit of a failure? Take heart from this lot [h/t Winnie Byanyima]

Latest aid stats. Good news: Global aid highest in history in 2014 ($137bn) . Bad news: Less going to to poorest countries.

The World Bank is hosting an excellent debate on knowledge & fragile states. Here’s Alex de Waal’s post.

‘Companies which do the most CSR also make the most strenuous efforts to avoid paying tax (& spend most on lobbying)’. Ouch.

Recognize this feeling? Just when you think you’ve got something good, it dissolves into nothingness [h/t Finlay Green]

The real Clinton-Blair transcripts – OK, it’s a spoof, but I don’t care, it’s still wonderful.

The real Clinton-Blair transcripts – OK, it’s a spoof, but I don’t care, it’s still wonderful.

Half a million Syrians didn’t hurt Turkish wages, according to some pretty rigorous research. Will Europe’s anti-immigrant lobby notice/acknowledge this awkward fact?

Excellent debunking of spread of meaningless corporatebabble in the aid biz [h/t Chris Jochnick]

Powerful plea from Open Society to defend civil society space from attack by governments around the world. 5m video

January 3, 2016

How many readers? Where from? What were their favourite posts? Report back on 2015 on FP2P

Hi there, I’m briefly emerging from writing purdah to do the usual feedback post on last year’s blog 2015 stats:

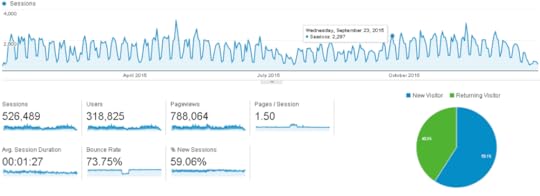

Overall: 318, 825 ‘unique visitors’ – not quite the same as ‘different readers’, as if you read the blog on your PC, laptop and mobile, that counts as 3 people. Within the year, the usual trend – a weekly cycle of low weekend reads, and summer and Christmas lulls (see graph). Those numbers represent a small (7%) increase on the previous year, but what is more striking is the similarity with previous years – however hard I try, the blog seems to have found its natural readership level!

Most-read Posts: these continue to surprise me – this year’s stock were a mixture of the geeky and industry insider guides and how-tos, plus a reassuring (given the impending book) level of interest in how change happens. Most of them were from previous years – interesting, given the reputation of blogging as a short term activity – they must  have made it onto some large reading lists. Only 2 of this year’s top 10 were actually published in 2015.

have made it onto some large reading lists. Only 2 of this year’s top 10 were actually published in 2015.

What are the limitations to a human rights based approach to development? Was, inexplicably, top of the pops – published in 2014, and only came 10th in that year, but has been picked up by someone, obviously.

How to get a PhD in a year and still do the day job (from 2011)

What is a theory of change and does it actually help? (from 2013)

How much should Charity Bosses be paid? (from 2013)

The world’s top 100 economies: 53 countries; 34 cities and 13 corporations (another 2011 post, down from last year’s number 1 slot)

How to write a really good executive summary (2014 post)

How is climate change affecting South Africa? (a 2009 post – the oldest in the list)

Where have we got to on theories of change – passing fad or paradigm shift?

Has Zimbabwe’s land reform actually been a success? A 2013 book review

The implications of complexity and systems thinking for aid and development – guest post from Owen Barder

I was sad to see ‘what Brits say v what they mean’ drop out of the rankings – may just have to repost it…..

Where were the readers from? Again very similar to last year, with Kenya the only new (and very welcome) entrant into the top 10.

Where were the readers from? Again very similar to last year, with Kenya the only new (and very welcome) entrant into the top 10.

If you can see any other patterns or useful lessons do let me know, but for now my main conclusions are

a) there is no way of telling in advance which posts will do best (very pleasing)

b) ‘how to’ posts are appreciated by the blog’s largely development wonk readership

c) the readership is mainly in developed countries, but well spread between them, and the developing country readership is rising (need to work on that).

What have I missed?

Right, that’s it from me – no more blogging til February – let the (suitably seasonal) cold turkey begin……

December 21, 2015

What happened when we put a draft book online and asked for comments? Report back on How Change Happens consultation

So the consultation on the draft of my forthcoming How Change Happens book is over, the draft has been removed  from the website (if you want to read it, you’ll have to wait til the book comes out next October). How did it go?

from the website (if you want to read it, you’ll have to wait til the book comes out next October). How did it go?

The draft went live at the end of October, allowing for six weeks of consultation before last Thursday’s deadline. In that time, I have discussed it in seminars with academics and practitioners in Washington, Boston, London, Birmingham, Oxford, Melbourne and Canberra. To compensate for the Western bias inherent in that travel schedule, there have been emails flying to and fro, trying (not always successfully) to get a wider range of voices feeding in on the text.

The main messages from readers? Still processing, but overall very encouraging. People particularly liked the case studies and the overall attempt to make issues accessible. Most liked the degree of personal anecdote dragged out of me by the editor, Mark Fried, though a few found it a bit icky.

They had lots to say on content and narrative. People particularly liked the chapters on power and systems, active citizens and advocacy. Some chapters were weak (rule of law, TNCs, leadership) and need strengthening; some issues and actors have gone missing (media, culture); the ‘so whats’ concluding chapter needs an overhaul and boiling down into a few bullet points that people can try and remember during their day jobs (thanks to my activist son Calum for banging that point home!) That narrative – especially the relevance of power and systems thinking – then needs to become a much more consistent thread throughout the book.

That’s just my first skim – I now have to sit down and go through 120 pages of comments from 40 ‘critical friends’, and that’s just the first instalment. Lots more are trickling in late (mainly from my esteemed Oxfam colleagues…..).

I’m a bit knackered, but am now entering ‘one more heave’ territory – taking all those inputs and using them to rewrite the text by the end of January. That will mean ‘going dark’ – no blogs from me, which after 7 years of pretty much daily blogging, is going to involve some serious withdrawal symptoms. If I don’t blog, do I actually exist?

Was it worth it? You bet: the quality of discussion and input has been outstanding. Someone asked me last week how I grew a thick enough skin to get through what has amounted to a 6 week long viva. Well, this time round, nothing came close to my afternoon being berated by a bunch of South African trots while consulting on From Poverty to Power. Anna Coryndon, the long suffering project manager on both books, reckons this time around ‘people weren’t using the consultation as an excuse to push their pet projects or positions – they were engaging with the draft text and enjoying the process. In many cases, they’d already been following the key themes via your blog.’

Was it worth it? You bet: the quality of discussion and input has been outstanding. Someone asked me last week how I grew a thick enough skin to get through what has amounted to a 6 week long viva. Well, this time round, nothing came close to my afternoon being berated by a bunch of South African trots while consulting on From Poverty to Power. Anna Coryndon, the long suffering project manager on both books, reckons this time around ‘people weren’t using the consultation as an excuse to push their pet projects or positions – they were engaging with the draft text and enjoying the process. In many cases, they’d already been following the key themes via your blog.’

But I have to admit it has got a bit edgy at times. When my ego was taking a battering, and I could hear myself becoming defensive or upset, I just listened to that little voice in my head saying ‘free consultancy, free consultancy. The final text will be immeasurably improved thanks to this process, so get over yourself’.

Finally, some ‘learnings’ (ugh) for anyone thinking of putting themselves through a similar mangle:

Everyone has good intentions, but most start reading, and then fall by the wayside (or go to sleep). As a result I have hundreds of comments on the first two chapters, and very few on the second half. I should have segmented the audience more and got people commenting on specific chapters.

I had too many general seminars – I now wish I had organized more of them around specific chapters.

Leave a lot more than 6 weeks to digest the results – everyone will send you shedloads of papers and books to read

Use pdfs, to deter the track changes obsessives

But above all, do it. The advice has been invaluable, and has hopefully generated lots of pre-promotion buzz. The book will definitely be better as a result, but it remains to be seen whether the consultation will undermine or improve sales (OUP crossing their fingers on that one). I haven’t told them yet, but there were 621 downloads of the total manuscript with, interestingly, a massive majority from the US (390), followed by the UK (42), Germany (37) and Australia (29). Is that the sound of sales reps screaming?

So, apart from a quick New Year report back on 2015, no more posts til I’ve finished the book (and that includes would-be guest bloggers, sorry). See you February (I hope)!

December 20, 2015

Links I Liked (and happy Christmas Elsie)

Wonderful readers’ selection of their favourite New Yorker cartoons. Enjoy.

What Should We Do About Inequality? Fascinating reflection from Harvard’s Ricardo Hausman

‘Since our campaign, we had seen a 90% reduction in LRA killings’. Relive the mind-blowing hubris of Invisible Children (of Kony 2012 fame), and a classic illustration of failing to distinguish between causation and correlation

100 key research questions for the post-2015 development agenda. One for all the blue sky-ers out there (and anyone looking for dissertation topics)

Who said it: Star Wars or the EU? Brighten yr Monday morning and take the quiz (I got 10/12) [h/t Hugh Cole]

Brilliant idea to show horrible reality. A pregnant woman’s 5 hour walk to nearest health centre, on video

Is responsible tax behaviour the next frontier of CSR? Excellent piece on norm shifts & tax activism

Excellent final reflection on the significance of the Paris Agreement on climate change by the IIED’s remorseless Saleemul Huq

And a big Christmas shout out to blog reader Elsie Russell in Christchurch, whose family is currently camping out in our house….

December 17, 2015

How to ensure increased aid to fragile/conflict states actually benefits poor people?

Following the UK government’s announcement of an increase in spending on aid for fragile states, Ed  Cairns, outlines Oxfam’s experience in fragile states and the potential lessons for the future.

Cairns, outlines Oxfam’s experience in fragile states and the potential lessons for the future.

The announcement that the UK will spend 50% of its aid budget in fragile states was made in the aftermath of the terrible atrocities in Paris, Beirut and Bamako. But it’s also the latest step in development agencies reframing their work in a world in which extreme poverty is disproportionately concentrated where violence is high, and where accountable states are pretty absent.

As Duncan reminded us recently, this transformation is neither new nor completed. 2011’s World Development Report on Conflict, Security and Development certainly gave it a push. This September’s Sustainable Development Goal (number 16) to ‘promote peaceful and inclusive societies’ seemed a high watermark. But we all know how difficult this is to get right, how much more must be done, and that governments and NGOs alike need new strategies to do so.

So far at least, the UK’s new target perhaps begs more questions than it answers, and I’ll come to them in a minute. But the bigger question for aid in fragile states really is: what works? In Pakistan, Afghanistan, South Sudan, the Philippines and elsewhere, Oxfam has developed programmes to help communities to cope with and at best reduce violence. We’ve seen that conflicts threaten everyone, but that women and girls face particular impacts. That is why we have supported women’s groups in a number of countries to have their voices heard in peace processes, and to seek security and justice from the state.

So far at least, the UK’s new target perhaps begs more questions than it answers, and I’ll come to them in a minute. But the bigger question for aid in fragile states really is: what works? In Pakistan, Afghanistan, South Sudan, the Philippines and elsewhere, Oxfam has developed programmes to help communities to cope with and at best reduce violence. We’ve seen that conflicts threaten everyone, but that women and girls face particular impacts. That is why we have supported women’s groups in a number of countries to have their voices heard in peace processes, and to seek security and justice from the state.

We’ve been funded by DFID to pilot new ways to support civil society in South Sudan, Yemen, Afghanistan, DR Congo and the Occupied Palestinian Territories. This is a stark recognition by DFID as much as us that too much donor policy on fragile states has been focused on building ‘effective’ but not necessarily accountable states, and that no society will be stable until its citizens (and civil society) can hold that state to account.

In too many countries, the state is not benign; it is predatory, requiring both donor governments and NGOs to put supporting civil society, and influencing the state at the heart of their strategy. In eastern Congo, for example, people say that ‘the community no longer trusts the authorities’, as our annual assessments of the threats people face repeatedly show. Even there however, real results are possible. Oxfam’s work with local ‘protection committees’ has not brought peace, but it has helped at least some communities achieve greater safety.

In truth, however, Oxfam’s own work in fragile states meets with progress and setbacks. We know that transformative change is unlikely within the few years that both NGOs and governments usually plan for. We must plan over far longer periods of 10 or 20 years in a way that allows us to adapt to the inevitable setbacks that will happen. And we need to be realistic about what aid can achieve in the absence of far wider change, which is precisely why we try to join our on-the-ground programmes and our influencing work so closely together.

In Somalia, for instance, many communities have been remarkably resilient despite years of conflict, not least because of the remittances which 40% of Somalis rely on. But in the past few years, banks, including in the UK, have become increasingly nervous of servicing that lifeline because of counter-terror and anti-money laundering regulations.

In other words, DFID can spend any percentage of its aid in fragile states, but there’s far more that must be done,  and that involves UK departments far beyond DFID. In September, Oxfam’s Chief Executive, Mark Goldring, wrote about the challenge to see DFID’s strategy in Yemen and British arms sales as coherent. On that kind of coherence, the new Strategic Defence and Security Review has not reassured me. There are good things in it, such as doubling the number of UK military contributed to UN peacekeeping, but it’s disappointing to see no commitment to vigorously implement the Arms Trade Treaty after the UK took ten years to help make it international law. We cannot build resilient states without tackling the international as well as local drivers of fragility, of which irresponsible arms transfers are surely one.

and that involves UK departments far beyond DFID. In September, Oxfam’s Chief Executive, Mark Goldring, wrote about the challenge to see DFID’s strategy in Yemen and British arms sales as coherent. On that kind of coherence, the new Strategic Defence and Security Review has not reassured me. There are good things in it, such as doubling the number of UK military contributed to UN peacekeeping, but it’s disappointing to see no commitment to vigorously implement the Arms Trade Treaty after the UK took ten years to help make it international law. We cannot build resilient states without tackling the international as well as local drivers of fragility, of which irresponsible arms transfers are surely one.

But let me return to DFID’s new 50% target. At least a third of the world’s most vulnerable people live in fragile and conflict-affected states, and some estimate that figure could rise to two-thirds. In that context, DFID’s target seems quite right. But there are risks, and some of those risks may be particularly prominent at a time when the UK and most donor countries face compelling security threats.

The government will spend that 50% ‘including in regions of strategic importance to the UK, such as the Middle East and South Asia.’ Oxfam itself helps provide aid to more than a million people in Syria, as well as millions more in Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq and Afghanistan, and other countries that are high on the UK’s security interests. But we must not turn our backs on Burundi or the Central African Republic or anywhere else where the lives of thousands, but probably not the interests of the UK, are at stake. We must remember those countries considered stable right now, as Syria, Egypt and Libya were five years ago, but where inequality, scarce resources or political oppression may increase their risks of violence in the future. And we must remember, as Syria shows only too well, that conflict and fragility affect many neighbouring countries, and so any list of fragile states should be treated with some flexibility.

A child holds up bullets collected from the ground in Rounyn, a village about 15 kilometres from Shangel Tubaya, North Darfur. Most of the villages population has fled to camps for internally displaced because of heavy fighting between Government of Sudan and rebel forces.

The government is right that security is vital for development. Equally, development is vital for security and so supporting development and poverty reduction in fragile states through wise use of the aid budget will result in real dividends for security. We must also remember that security is not just about establishing robust states, but also about human security for the people of developing countries, which means ensuring that justice, accountability and upholding human rights are key components of any strategy for working in fragile states.

Those points should inform not only where DFID’s 50% is spent – not disproportionately on ‘regions of strategic importance’ to the UK. It should also inform any debate on the OECD guidelines on what counts as Official Development Assistance. The UK has always championed the strict use of those guidelines, and to its great credit, it has hit the 0.7% target without weakening those rules. The last thing it should do now is to join with any other governments pressing to spend ‘aid’ to tackle the security or terrorist threats that they, rather than developing countries, primarily face.

In announcing DFID’s 50% target, David Cameron repeated a phrase he has used often before: that the UK will ‘keep our promises to the poorest in the world.’ That certainly means spending 0.7% of GNI on aid. It also means spending it on the purposes promised – on tackling poverty, inequality and humanitarian crises in fragile states and other developing countries – now and in the future.

December 16, 2015

Will the Sustainable Development Goals make a difference on the ground? Lessons from a 5 country case study on the MDGs

I’ve long been baffled/appalled by the lack of decent research on the impact of the MDGs at national level. Sure  there’s lots of data gathering, and reports on how fast access to education or health is improving or poverty is falling, but that’s definitely not the same thing as finding out whether/how the MDGs in particular are responsible for the changes (rather than, say, economic growth, democracy or aid). That matters because the UN is now deciding how the successors to the MDGs, the Sustainable Development Goals, are to be implemented, so it would be helpful to have some lessons from the MDGs in terms of how the SDGs could exert traction on decision-making at national or subnational level.

there’s lots of data gathering, and reports on how fast access to education or health is improving or poverty is falling, but that’s definitely not the same thing as finding out whether/how the MDGs in particular are responsible for the changes (rather than, say, economic growth, democracy or aid). That matters because the UN is now deciding how the successors to the MDGs, the Sustainable Development Goals, are to be implemented, so it would be helpful to have some lessons from the MDGs in terms of how the SDGs could exert traction on decision-making at national or subnational level.

Now the ever-industrious ODI has had a go at filling the void, with a new paper ‘National MDG implementation: Lessons for the SDG era’ by Moizza Binat Sarwar. It studies MDG implementation in five low and middle income countries (Indonesia, Liberia, Mexico, Nigeria and Turkey), largely by interviewing staff of relevant ministries.

It concludes:

‘The response of all five countries to the MDGs unfolded in similar ways over the period 2000-2015. While the discursive effect of MDGs on policy language occurred fairly quickly after 2001, institutional commitments to the MDGs became more visible around the 10-year mark.

‘The response of all five countries to the MDGs unfolded in similar ways over the period 2000-2015. While the discursive effect of MDGs on policy language occurred fairly quickly after 2001, institutional commitments to the MDGs became more visible around the 10-year mark.

The 10-year gap could be attributed to a policy lag between international commitments and national adaptions, since countries were already working on targets they had set before 2000 and the MDGs only gained political traction once it was time for previous priorities to be renewed.

In the case of LIC governments, it is clear that their external relationships with international donors and development partners have led them to invest in making the political signals that show an overt (if not accurate) interest in furthering MDG objectives.

Similarly MIC governments have also invested in projecting commitment to MDGs internationally to further their regional standing.’

Five lessons for the post-2015 era

Countries are more likely to succeed in those international goals where they already have priorities in place. MDGs in both low and middle-income countries have been used to reinforce existing policies. For the SDGs, more work will be needed in areas that are highly politically contentious (such as climate change) to ensure that international targets are echoed in national targets.

Monitoring agencies will need to be realistic about how long it will be before SDG progress becomes visible. Given that the development of the SDGs has been a broadly consultative process and countries have already been implementing MDGs, it is possible that the post-2015 era will see a much quicker implementation response. However, civil society organisations will have a significant job to keep up the pressure on national government, particularly given that the SDGs cover a wider range of targets than the MDGs.

Given how national priorities can and are often different from the needs of local areas, an important point of discussion is whether the MDGs would have had more political traction if engagement with the goals had been more localised. It is possible that poorer and more deprived regions could use political language around the MDGs to mobilise resources from the centre to address the targets they have done less well on.

The motivations for MICs in adopting the MDGs is different from that of the LICs studied in this paper. MICs engaged with the MDGs to further strategic regional interests. Meanwhile LIC governments’ subscription to the language and process of the MDGs appears to be linked to accessing ODA [i.e. aid] linked to the MDG targets. For the SDGs this implies that international donors need to engage in different ways accordingly, and that national civil society organisations will be important in furthering the SDG agenda.

There has been a dearth of research on the implementation of MDGs within national contexts.’

All really useful, but the report falls down on one very basic point – causality. As it acknowledges, in such a complex, messy and extended process, it is really hard to attribute changes in, say, poverty, to the MDGs rather than, for example, growth, good government, or aid.

The report returns regularly to this thorny issue, but I think it could have gone further in establishing causation in at least two ways:

Process tracing would have allowed a more informed discussion about the different possible explanations for progress, allowing a more informed degree of attribution to the MDGs relative to other potential causes

Alternatively, the research could have not mentioned the MDGs at all, but asked a) what were the factors behind your country’s progress on X and/or b) of all the international instruments your country has signed up to, which ones do you, working in the ministry, feel have exerted real pressure on your decision making?

Either approach would have got the paper further on the attribution question, although I’m sure it wouldn’t have finally nailed it. But I’m pretty rubbish at methodology, so would be interested to hear other suggestions about how to crack this problem.

So thanks to ODI and in particular to Moizza Binat Sarwar, we now know a bit more about the MDGs process, but huge doubts remain, and I still think that it is scandalous that we have such a thin evidence base when so much political and other capital has been invested in the SDGs. See here for the only other decent effort I have come across on this – a 50 country study that came to broadly similar conclusions to the ODI paper. Here’s me on the SDGs (lack of) theory of change and a recent Claire Melamed piece on implementation.

December 15, 2015

Is Paris more like Kyoto or Montreal?

Celine Charveriat, (@MCcharveriat) Oxfam’s Director of Advocacy & Campaigns, looks at what happens  next and when/why international agreements actually get implemented.

next and when/why international agreements actually get implemented.

As the ink of the new Paris agreement is not yet dry, many are wondering whether this partly-binding package, which is not a treaty, stands any chance of reaching its target of capping global warming at a maximum 1.5 degree increase. After all, its predecessor, the Kyoto protocol, whose legal form was much stronger, was not implemented by many of its signatories.

In contrast, the Montreal protocol, the agreement regulating chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), which contribute to the depletion of the Ozone Layer, has been a huge success: With 197 nations party to the accord, including the US, the most widely ratified treaty in UN history has enabled reductions of more than 97% of all consumption and production of controlled ozone-depleting substances, with $3.5 billion investment resulted in an estimated $1.8 trillion in global health benefits and avoided damages to agriculture, fisheries and material worth $460 billion. That’s equivalent to around $650 per dollar invested. With returns like this, even the euro million lottery or the Ponzi Pyramid look like  low return investment schemes. On top of that, the Montreal Protocol did more for climate change than Kyoto did – 10 gigatonnes carbon dioxide equivalent (Gt CO2E , the unit of avoided CO2 emissions) avoided per year in 2010, which is 5 times the annual reduction target for the Kyoto protocol over 2008-2012.

low return investment schemes. On top of that, the Montreal Protocol did more for climate change than Kyoto did – 10 gigatonnes carbon dioxide equivalent (Gt CO2E , the unit of avoided CO2 emissions) avoided per year in 2010, which is 5 times the annual reduction target for the Kyoto protocol over 2008-2012.

What explains such a massive success? The agreement got off to a very good start: DuPont the world’s largest CFC producer, with 25 percent of the market share decided in 1988 that it would stop manufacturing CFCs. This had an enormous impact on the rest of the industry. Moreover, the key demands from developing countries: flexibility, the recognition of differentiated responsibilities and finance, were enshrined in the agreement and a multilateral fund for developing countries and economies in transition provided over US$3.3 billion of support. The agreement had vastly underestimated the extent of reductions needed but included provisions for taking stock and adjusting targets, enabling parties to use new science to adjust their controls. Also underestimated was the capacity of industry to adapt: projected costs for industry were much lower than originally expected.

So what does this tell us about the odds of implementing the Paris agreement?

It would be decisive if a major oil company decided to break ranks: Any volunteers? How can we make this happen?

The message that climate finance is an intelligent investment rather than charity is not getting through to rich

No ostriches please

governments and climate negotiators, so please repeat after me: “Supporting developing countries to implement international environmental agreements is an investment which provides amazing returns”

Learn and adjust rapidly, and do so based on science not politics

Don’t ever listen to losers…because losers are losers. They lie until they die. Just look at tobacco companies….

The twist in this tale of two agreements is that Montreal might end up sinking or saving Paris: rising demands for HFCs, which replaced CFCs, could lead to emissions equivalent to 8.8 gigatonnes carbon dioxide equivalent per year by 2050 or 20% of annual CO2 emissions. The silver lining is that parties to the Montreal protocol have agreed to come back to the negotiation table in 2016 to explore phasing out HFCs, with enormous co-benefits for climate change, equivalent to eliminating the annual greenhouse gas emissions from 40 percent of all U.S. passenger cars each year, for the next 30 years. If they succeed in doing so, only one conclusion can be reached: it is always a good idea to sign environmental agreements in francophone cities. This is why the next UNFCCC Conference Of Parties, in Morocco, is bound to be a success. As we say in French math classrooms, CQFD (Ce Qu’il Fallait Demontrer)!

December 14, 2015

How on earth can you measure resilience? A wonk Q&A

Resilience is one of today’s omnipresent development fuzzwords, applied to individuals,

Resilience is one of today’s omnipresent development fuzzwords, applied to individuals,  communities, businesses, countries, ideas and just about everything else. But how can it best be measured? To plug their new paper on the topic, Oxfam’s measurement wonks Jonathan Lain (left) and Rob Fuller (right) argue with their imaginary non-wonk friend……

communities, businesses, countries, ideas and just about everything else. But how can it best be measured? To plug their new paper on the topic, Oxfam’s measurement wonks Jonathan Lain (left) and Rob Fuller (right) argue with their imaginary non-wonk friend……

So they’ve let the beancounters loose on resilience now. Do we really have to measure everything?

Well, look at it this way: Oxfam projects are focusing more and more on helping people to build their resilience to shocks, stresses and uncertainty. If we want to evaluate the success of these projects and learn from them, then we need to know what outcomes we’re looking for. This means we need a way to think about and to measure resilience.

But can’t you see how resilient people are simply by looking at how well they’ve been able to deal with crises?

But can’t you see how resilient people are simply by looking at how well they’ve been able to deal with crises?

Sometimes, yes. Ideally, if we wanted to see whether Oxfam projects have succeeded in building resilience, we would wait and see what happens after people have experienced some actual crises. But often we are trying to evaluate projects that are still ongoing, or that have recently ended. In some cases a crisis may have happened since the end of the project and we can ask people about how they coped: whether they had enough food, whether they lost any livestock or other assets, and so on. But in most cases there has (thankfully) not been a major crisis since the project was carried out. So we have to figure out whether the project that is being implemented now or in the recent past will help people to deal with crises and stresses in the future.

That sounds tricky.

Sure is. The best way we’ve found to deal with this is to identify some characteristics that we think will enable people to cope better with shocks in the future, and then look to see whether households or communities in the project area have those characteristics. Owning assets or having savings are obvious examples. But we also try to think more widely than that: Can people count on support from their neighbours when they need it? Are people aware of climate change and its effects? Do people participate in community groups? Considering these issues has proved useful in many of our previous evaluations of resilience-building projects.

How do you know what the right indicators are?

In a nutshell, we talk to a lot of people who know the local context well, and ask them what characteristics they think  a resilient household has. Usually this means a combination of doing focus groups with local people, spending lots of time discussing with local Oxfam and partner organisation staff, and reading whatever reports or studies already exist on resilience in the area. This guides us on what questions we should include in our surveys in order to measure resilience effectively.

a resilient household has. Usually this means a combination of doing focus groups with local people, spending lots of time discussing with local Oxfam and partner organisation staff, and reading whatever reports or studies already exist on resilience in the area. This guides us on what questions we should include in our surveys in order to measure resilience effectively.

For example, when we were working in a peri-urban area in Bolivia, many people said that resilience depended mainly on whether or not they had a salaried job. Of course in other places, regular employment is much less of a factor: for example, in Somaliland, people were mainly concerned about having basic access to water, grazing land, and veterinary care – all factors that help to sustain pastoralist and agro-pastoralist livelihoods.

But hold on! If you are coming up with different sets of indicators in each place, you can’t compare the results between countries.

Well, yes and no. We are not trying to create a universal standard measure of resilience. That would be much harder (some might say impossible). So, we cannot say whether people in peri-urban Bolivia are more or less resilient, in general, than people in rural Somaliland. However, what we can say is whether our projects have had more or less impact in each country where we do a survey. When we compare across countries, we effectively normalise or adjust our results according to the average levels of the specific indicators that we used in that context. We can, in fact, compare the percentage change in resilience that our projects brought about in peri-urban Bolivia and rural Somaliland. So even if we aren’t aiming for a universal standard measure, we can at least pull together the results from our evaluations of resilience-building projects.

This approach is all very well for indicators about how people can cope with crises in the short term. But isn’t the idea of resilience bigger than that?

This approach is all very well for indicators about how people can cope with crises in the short term. But isn’t the idea of resilience bigger than that?

Agreed. The examples we mentioned before could be indicators of people’s ability to deal with crises when they happen. But just as important is whether people can adapt proactively, so they are less vulnerable in the future. That might depend on factors like access to credit, but also on personal, psychological characteristics, such as whether people feel able to take a risk by changing their livelihood or making an investment. It’s harder to find indicators of these more subjective characteristics, but we’ve been experimenting with some different approaches.

Then there’s the issue that resilience is also about transforming the systems that people live in – the village, the region, the country, or even the world… If our projects can change the way these systems work – for example, by advocating for policy change or protecting the environment – we can limit the stream of shocks and stresses that people face. In many of our previous evaluations, we have tried to measure resilience simply by collecting large-N data through household surveys. But if resilience is also about stuff that happens at the level of the system – the village, the region, and so on – then it also makes sense to collect small-N data at the system-level too. This is exactly what we have been trying to do. For an example of the kind of rigorous qualitative techniques we want to incorporate into framework for measuring resilience, see this previous blog post on ‘Process Tracing’ by Claire Hutchings.

This is all work in progress, and we are constantly feeling our way and trying to improve our methods for thinking about and measuring resilience. If you would like more detail, please read our new paper. And, if you’d like a deeper dive into Oxfam’s resilience Effectiveness Review evaluations, including the newly published set, they can be accessed here.

December 13, 2015

Links I Liked

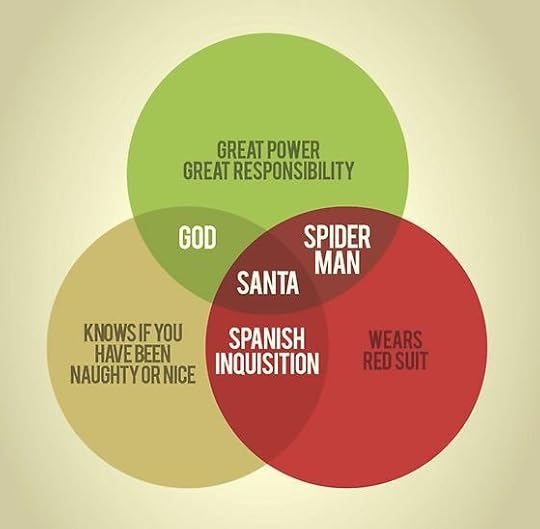

Christmas looms, but how do you tell Santa from Spiderman? Geek humour via @patronsaintofcats

Good tips on how to improve collaboration between academics/researchers and practitioners – because we need each other.

Malaria deaths have halved since 2000 (438,000 in 2015; 839,000 in 2000), according to new WHO figures

What refugees ask IRC staff when they reach Europe. No 1: ‘where am I?’ No 2: ‘Do you have WiFi?’ [h/t Chris Blattman]

Check out the v cutting Development Dictionary, storified by Tom Murphy

Check out the v cutting Development Dictionary, storified by Tom Murphy

Brilliant dissection of the new UK aid strategy by Owen Barder

Kinder eggs v guns: The world, or at least the US, seriously has to look at its child safety priorities

If you’re even vaguely interested in the role of tech in development, sign up to Tom Steinberg’s new blog. Here he is on new digital institutions (I love the idea of digital graveyards, but hope he includes cremation as an option)

Excellent Brookings Institution analysis of China’s recent $60bn pledge to Africa, including a shift from natural resources to labour-intensive industry

Loving these 30 sec positive ‘Friday lunchtime treats’ from Emma Greaves and friends at Oxfam. No 3: show us your dance moves

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers