Duncan Green's Blog, page 148

February 25, 2016

Which of these 3 How Change Happens covers do you prefer? Vote now!

Many years ago, around the time of the invention of the printing press, interweb, I worked in a small publisher and was given a ‘guide to handling authors’. One passage stayed with me – publishers should expect authors to throw a hissy fit when they first see roughs for the cover design. It’s their first chance to vent their anxieties and blame someone else for the book’s impending disaster. So when OUP showed me the roughs for How Change Happens, which now even has a webpage, I bit my tongue, smiled sweetly (very difficult combination, that) and suggested that, in the same way we invited comments on the draft text, we put the short-listed designs to the vote by you, the prospective readers.

So here are the 3 designs. Please vote for your favourite, and leave any suggestions for further improvements in the comments section. Needless to say the result is not binding, but it will be helpful.

Note: There is a poll embedded within this post, please visit the site to participate in this post's poll.

Over to you. Here are the three candidates:

February 24, 2016

Trying to promote reform in fragile and conflict states: some lessons from success and failure

Reading the ODI’s prodigious output is starting to feel like a full time job. A lot of it is really top quality, even if  their choice of titles is sometimes a bit bland. One example is ‘Change in Challenging Contexts’, a name that doesn’t exactly set the pulse racing – a shame, as it’s a fascinating set of papers.

their choice of titles is sometimes a bit bland. One example is ‘Change in Challenging Contexts’, a name that doesn’t exactly set the pulse racing – a shame, as it’s a fascinating set of papers.

The papers (a 54 page whopper, plus 3 briefings) are a ‘lesson-learning series produced by ODI’s Budget Strengthening Initiative (BSI), an experimental 5 year programme set up in 2010 to support fragile and conflict-affected states to build more effective, transparent and accountable budget systems.’ The BSI worked in Democratic Republic of the Congo, Liberia, South Sudan and Uganda and with the g7+ group of fragile states. That means it is very much about insider reform efforts by Big Aid, rather than protests on the streets and civil society activism etc, but even non-insiders can learn a lot about how government systems work, and can be reformed.

The starting point for the project is:

‘Significant progress in the development of processes, systems and capacity has been achieved in Liberia, South Sudan, Uganda and elsewhere, but appears to have had little effect on outcomes. Behaviour often has not changed significantly in areas where systems are developed. This suggests that while form may be changing, functions are not. Even so, incremental, positive changes in behaviour can be seen in some areas, which in some cases have resulted in steps towards improved outcomes. What are the clues to such genuine change?

Reforms that directly attempt to exert ex -ante controls in areas where power and interests are not aligned are unlikely to be successful. Conversely, reforms that protect and make progress in areas where interests are aligned or that strengthen ex-post processes such as accounting and transparency are more likely to succeed. The unpredictable nature of fragile and conflict-affected states also means that the space for reform is often changing, which also contributes to the frequent reversals that are seen alongside progress. Nevertheless, these fluctuations also present opportunities.

Reformers are always there, although the caricature of a charismatic, articulate, sociable ‘driver of change’ is a rarity. Although ministers and senior bureaucrats may or may not show active interest in reform, they often allow (or sometimes block) reform to take place. They provide the authority for (genuine) reform. There are always some mid-level managers or junior bureaucrats who are genuinely interested in positive change and keen to address the challenges around them. Such individuals can be instrumental in achieving change. When these managers led core teams of technocrats who achieved reform and built broader coalitions of support, then genuine change was more likely.’

The papers distil ‘ten tips for reformers’:

Start with a problem and an opportunity, not a comprehensive solution.

Understand the space for reform.

Take small steps, but know where you’re heading.

Start processes and systems on the right foot and sustain them.

Learn and adapt and you’ll avoid getting trapped

Decide when, what and how to formalise.

Join the dots. (eg linking up with reform initiatives in other ministries)

Don’t try and reform alone. (lot of emphasis on building reform teams of middle managers)

Those in authority provide and protect the space for change.

Seek and adapt external advice.

There’s a great critique of standard donor approaches to these issues:

‘Donor representatives tend to be rewarded if their programmes are visible and they can demonstrate clear influence and results. Results need to be defined during the design phase, and Technical Assistance (TA) projects often involve pre-planned activities. There are strong incentives to ensure that logframes and workplans are implemented as originally planned, but few incentives to understand problems, acknowledge mistakes, learn from them and adapt project design. Relationships are focused on ministers rather than on middle-level reformers. Information can be obtained from a donor contractor or donor employee within a ministry. Donor incentives can therefore serve to undermine the ability of donor representatives and TA providers to build relationships of trust and ultimately thwart genuine change processes.’

And in the main report, an excellent table on the reform opportunities presented by different kinds of crisis:

This is just a skim – there’s a lot more meat in here, and if you are interested either in How Change Happens, or Fragile/Conflict states (which is where the aid business looks likely to end up within the next decade or two, as the stable places graduate out of aid), I encourage you to go and dig for yourself.

February 23, 2016

Doing Problem Driven Work, great new guide for governance reformers and activists

One of the criticisms of the big picture discussion on governance that’s been going on in networks such as Doing Development Differently and Thinking and Working Politically is that it’s all very helicopter-ish. ‘What do I do differently on Monday morning?’, comes the frustrated cry of the practitioner. Now some really useful answers are starting to come onstream, and I’ll review a few of them.

One of the criticisms of the big picture discussion on governance that’s been going on in networks such as Doing Development Differently and Thinking and Working Politically is that it’s all very helicopter-ish. ‘What do I do differently on Monday morning?’, comes the frustrated cry of the practitioner. Now some really useful answers are starting to come onstream, and I’ll review a few of them.

First up is ‘Doing Problem Driven Work’, a paper by Matt Andrews, Lant Pritchett and Michael Woolcock. It turns previous work on PDIA – ‘problem-driven iterative adaptation’ – into a toolkit, aimed primarily at those involved in reforming governance from the inside, whether government reformers, or big bilateral and World Bank donors with access to the corridors of power. However, there are clear parallels with and lessons for the work of more ‘outsider’ NGOs and campaigners.

It starts by noting that while many reform projects have failed in the past, those that succeeded often involved a ‘problem focus’. Problems ‘force policymakers and would-be reformers to ask questions about the incumbent ways of doing things’ and ‘provide a rallying point for coordinating distributed agents who might otherwise clash in the change process’. ‘Good’ problems are urgent and can be easily addressed by those in the room. They often spring from crises or other ‘critical junctures’.

The first step for a would-be reformer is ‘problem construction’, which ‘involves gathering key change agents to answer four questions: ‘What is the problem?’, ‘Why does it matter?’, ‘To whom does it matter?’, ‘Who needs to care more?’ and ‘How do we get them to give it more attention?’’ Defining the problem is key: it’s no good having a woffly ‘corruption is a problem’ type statement – you need ‘a real performance deficiency that cannot be ignored’, like ‘we can’t get education and health care to these communities, because the municipal officials keep nicking the money’.

Once you have a problem, you can get started, with your doughty band of reformers:

What is the problem? (and how would we measure it or tell stories about it?)

Why does it matter? (and how do we measure this or tell stories about it?) Ask this question until you are at the point where you can effectively answer the question below, with more names than just your own.

To whom does it matter? (In other words, ‘who cares? other than me?) Who needs to care more? How do we get them to give it more attention? What will the problem look like when it is solved? Can we think of what progress might look like in a year, or 6 months?

The authors stress the importance of ‘authority’. For insider reformers like them, the key is to get political backing for the reform, preferably from the president or similar, which opens doors and aligns incentives.

Authority forms part of a ‘triple A change space analysis’, together with ‘acceptance’ and ‘ability’:

We can do better…..

Authority to engage

Who has the authority to engage: Legal? Procedural? Informal? Which of the authorizer(s) might support engagement now? Which probably would not support engagement now? Overall, how much acceptance do you think you have to engage, and where are the gaps?

Acceptance

Which agents (person/organization) has interest in this work?

For each agent, on a scale of 1-10, think about how much they are likely to support engagement?

On a scale of 1-10, think about how much influence each agent has over potential engagement?

What proportion of ‘strong acceptance’ agents do you have (with above 5 on both estimates)?

What proportion of ‘low acceptance’ agents do you have (with below 5 on both estimates)?

Overall, how much acceptance do you think you have to engage, and where are the gaps?

Ability

What is your personnel ability?

Who are the key (smallest group of) agents you need to ‘work’ on any opening engagement?

How much time would you need from these agents? What is your resource ability?

How much money would you need to engage?

What other resources do you need to engage? Overall, how much ability do you think you have to engage, and where are the gaps?

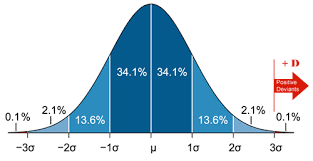

The questions also highlight some of the weaknesses of PDIA – there’s no power analysis here, for example, whether some people who are currently not involved in decision-making could become so, and what might enable them to do so; who are the blockers, and do they operate through the exercise of visible or hidden power? A good power analysis would definitely lead to more refined tactics. There’s also a lack of a real systems approach, for example looking for positive deviants that are already working, or emergent hybrid institutions that combine new and traditional approaches. It all feels quite top down and traditional.

On the other hand, I like the bottom-up construction of problem and solution, and the authors have been out there, doing this kind of work for years, so the paper is full of practical examples.

I’d be interested in what people think.

February 22, 2016

Why we should be interested in the rise of the Pentecostals

Maybe it’s my Latin America background, but I’ve always been fascinated by the rise of evangelical Christianity, and  its potential social and political impact. Religion in general is an inexcusable blind spot for a lot of the aid business, and activists are particularly alarmed by the kind of happy clappy Protestant churches who go in for guitars, ecstasy, speaking in tongues etc. But they play a huge and growing role in the lives of poor people and communities around the world, so we need to get over it. To help, there was a fascinating series of articles in a recent Economist about the state of Global Pentecostalism.

its potential social and political impact. Religion in general is an inexcusable blind spot for a lot of the aid business, and activists are particularly alarmed by the kind of happy clappy Protestant churches who go in for guitars, ecstasy, speaking in tongues etc. But they play a huge and growing role in the lives of poor people and communities around the world, so we need to get over it. To help, there was a fascinating series of articles in a recent Economist about the state of Global Pentecostalism.

There’s an overview, and then country profiles on Brazil and South Korea (both hotbeds). For those of you unwilling to hand over your dosh to the evil neoliberals for a subscription, here are some highlights:

‘Like migrants in search of safety and prosperity, charismatic Christianity has proved adaptable, almost chameleonic. To people whose lives are in flux, it offers a mix of ecstasy, discipline and professional and personal support. In Brazil an initially sober kind of Pentecostalism has been replaced by a brasher kind. In South Korea, a style of worship that suited a poorish, insecure country has been replaced by one that flaunts success.

Whatever their style, Pentecostal pastors are culturally closer to their flock than are the learned clerics of the Catholic or Lutheran churches; and they are numerous. A study in 2007 found that in Brazil Pentecostal churches had 18 times more clerics per believer than the majority Catholics. Older churches move slowly because they are lumbered with hierarchies and rules; the Pentecostal world is one of quick startups, low barriers to entry and instant reaction to change.

At worst, this flexibility shades into opportunism. In every country where Pentecostalism has thrived, its leading practitioners have faced investigations of their finances. In 2011Forbes magazine estimated the combined worth of five Nigerian pastors as at least $200m. In Brazil the faithful seem tolerant of pastors who are light-fingered with their tithes; many see giving as a virtuous act, regardless of the money’s ultimate destination. Estevam Hernandes, one of Brazil’s best-known preachers, cheerfully resumed his career after returning, in 2009, from five months in an American jail for smuggling undeclared cash.’

At worst, this flexibility shades into opportunism. In every country where Pentecostalism has thrived, its leading practitioners have faced investigations of their finances. In 2011Forbes magazine estimated the combined worth of five Nigerian pastors as at least $200m. In Brazil the faithful seem tolerant of pastors who are light-fingered with their tithes; many see giving as a virtuous act, regardless of the money’s ultimate destination. Estevam Hernandes, one of Brazil’s best-known preachers, cheerfully resumed his career after returning, in 2009, from five months in an American jail for smuggling undeclared cash.’

The link to migration: ‘In the past migrating religious groups either merged into their host societies or else pickled the culture of the old country in aspic. Thanks to technology, today’s roaming worshippers have no such dilemma; a Nigerian or Brazilian in transit can adapt while maintaining contact with home. Globally dispersed Pentecostal churches meet both those needs. An outlying branch of the RCCG can offer job advice and a way to keep links with home. Global charismatic movements act as transmission belts along which ideas and worship styles can travel quickly.’

Are evangelical churches always right wing?: ‘Politically, Pentecostal churches tend to be pragmatic rather than consistently conservative. Brazil’s globally successful Universal Church of the Kingdom of God (UCKG) initially resisted the rise of the centre-left Workers’ Party, but went on to back its presidential candidates, including Dilma Rousseff, the incumbent. In Ukraine Mr Adelaja was close to the 2004 Orange revolution but also wooed the pro-Russian president, Viktor Yanukovych. Peru’s right-wing authoritarian leader, Alberto Fujimori, enjoyed Pentecostal support, but in El Salvador, Pentecostal preachers strike a leftist tone. In America Latino Protestants (mostly charismatic) are contested electoral terrain. Almost all Pentecostal churches are anti-abortion and anti-gay, but the UCKG has made statements that are pro-choice and comparatively gay-friendly’

In Brazil Roman Catholics remain more numerous, but ‘One study found that in 2002-03, when they made up 13% of Brazilians, Pentecostals gave 44% of tithes collected by churches in Brazil; Catholics, then 74% of the population, paid less than a third.’

February 21, 2016

Where are the ‘Digital Dividends’ from the ICT Revolution? The new World Development Report

OK, book done, back from recuperative holiday, time to get back to daily blogging.

Earlier this month I headed off for the London launch of the 2016 World Development Report, ‘Digital Dividends’.  The World Bank’s annual flagship is always a big moment in wonkland, and there has been a lot of positive buzz around this one.

The World Bank’s annual flagship is always a big moment in wonkland, and there has been a lot of positive buzz around this one.

Here’s how the Bank summarizes its content:

‘What is the Report about? It explores the impact of the internet, mobile phones, and related technologies on economic development.

What are the digital dividends? Growth, jobs, and services are the most important returns to digital investments.

How do digital technologies promote development and generate digital dividends? By reducing information costs, digital technologies greatly lower the cost of economic and social transactions for firms, individuals, and the public sector. They promote innovation when transaction costs fall to essentially zero. They boost efficiency as existing activities and services become cheaper, quicker, or more convenient. And they increase inclusion as people get access to services that previously were out of reach.

Why does the Report argue that digital dividends are not spreading rapidly enough? For two reasons. First, nearly 60 percent of the world’s people are still offline and can’t fully participate in the digital economy. There also are persistent digital divides across gender, geography, age, and income dimensions within each country. Second, some of the perceived benefits of the internet are being neutralized by new risks. Vested business interests, regulatory uncertainty, and limited contestation across digital platforms could lead to harmful concentration in many sectors. Quickly expanding automation, even of mid-level office jobs, could contribute to a hollowing out of labor markets and to rising inequality. And the poor record of many e-government initiatives points to high failure of ICT projects and the risk that states and corporations could use digital technologies to control citizens, not to empower them.

Cup Half Full version

What should countries do to mitigate these risks? Connectivity is vital, but not enough. Digital investments need the support of “analog complements”: regulations, so that firms can leverage the internet to compete and innovate; improved skills, so that people can take full advantage of digital opportunities; and accountable institutions, so that governments respond to citizens’ needs and demands. Digital technologies can, in turn, augment and strengthen these complements—accelerating the pace of development.

What needs to be done to connect the unconnected? Market competition, public-private partnerships, and effective regulation of internet and mobile operators encourage private investment that can make access universal and affordable. Public investment will sometimes be necessary and justified by large social returns. A harder task will be to ensure that the internet remains open and safe as users face cybercrime, privacy violations, and online censorship.

What is the main conclusion? Digital development strategies need to be broader than ICT strategies. Connectivity for all remains an important goal and a tremendous challenge. But countries also need to create favorable conditions for technology to be effective. When the analog complements are absent, the development impact will be disappointing. But when countries build a strong analog foundation, they will reap ample digital dividends—in faster growth, more jobs, and better services.’

I found the tone of the launch actually more downbeat than the report. Deepak Mishra, its lead author, told me he was surprised by how depressing the picture was – he was expecting more evidence of a positive impact of ICT.

The findings on inequality were particularly worrying – ICT has an inherent disequalizing tendency and needs strong

Cup Half Empty

institutions to counteract winner-takes-all market concentration rapidly followed by political capture (Google anyone?) and its impact in automating jobs in the the soft, replaceable centre between high skill and manual labour. Feels like we’re running up a down escalator on that one.

Everyone was very excited by the recognition of the importance of ‘analog complements’ (what most of us refer to as real life – skills, institutions, power, politics etc). I both shared that, and thought ‘well duh, what did you expect?’ The cycle is endlessly repeated: a new magic bullet, rapidly turned into a straw man (‘solving poverty one app at a time’ – does anyone really think that?). Then someone takes a cold hard look at the evidence and concludes that it’s all about the institutions, governance etc.

Two areas where the report could have taken this further, in my view.

Two areas where the report could have taken this further, in my view.

Where’s the history? The report is stuffed full of ‘positive deviants’ in the shape of companies, governments and campaigners who have used ICT well. I would have liked some more historical perspective though – why did some countries become outliers on this; what’s different about Estonia (home of skype and a digital hub)? I asked Deepak and his reply was fascinating: In 1991, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Estonia resembled Korea, Japan, Germany after World War 2 – it was creating institutions from scratch so able to incorporate new ones without opposition from vested interests. It also had neighbourhood effects, namely ‘Finland envy’. OK, but why Estonia, rather than the other post Soviet states?

Learning from the governance debate. The report reminds me of the evolution of the governance debate, but hasn’t gone as far. It seems to have gone from a simplistic supply side (build it and they will come) to a more sophisticated supply side (add skills, institutions and regulate). But it didn’t discuss the demand side – what makes citizens or business pick up ICT and use it? What role for social norms, levels of trust etc? And it didn’t discuss the governance approaches that try to supersede the supply-demand division such as PDIA (get everyone together to work on a commonly recognized problem) or creating hybrid institutions between traditional/informal and modern. It feels like there must be digital equivalents of those conversations – a bit more cross-disciplinarity would have helped there.

Here’s Ben Ramalingam’s take on the launch event and the report. Any other thoughts or recommended reviews?

And here’s one of the five promo videos accompanying the report, a great account of how the internet allowed a disabled entrepreneur to set up a business in China

February 8, 2016

Links I Liked

I’m off for a holiday, so this is the last blog for a couple of weeks. Back after that.

Let’s make 2016 the year when we try and stop people unthinkingly hit ‘reply all’ and clogging up our inboxes. Next time someone does it, why not send them this photo?

In Kerala, Pembillai Orumai—Women’s Unity, an organization of Dalit tea workers won a strike, and then moved on to change politics too

Some good aid biz nuts and bolts posts this week:

Is My NGO Having a Positive Impact? Evaluation 101 and the problem of the counterfactual

How to design a monitoring and evaluation framework for a policy research project.

The extraordinary wasteland of Homs, Syria, filmed by a Russian drone. The sorrow and waste of war.

After complaints, JK Rowling locates the world’s oldest wizarding school in Uganda.

After complaints, JK Rowling locates the world’s oldest wizarding school in Uganda.

Last week, Alphabet (aka Google) overtook Apple to become the world’s largest company by market cap. Time to pay some more tax, then?

Delhi’s odd-even plan to reduce pollution was a rather successful experiment in public policy and citizen participation

It turns out that paying officials better doesn’t reduce corruption after all. In fact the opposite. Oops. New Ghana study.

Did Ebola lead to a rape epidemic in West Africa? V disturbing piece

When Denmark clamped down and started demanding assets from refugees, some critics argued that Denmark should put its own old people first. Step forward African Adopt-a-Dane project

February 7, 2016

Book Review: The Power of Positive Deviance

Another contribution to this week’s conference on ‘Power, Politics and Positive Deviance’, which I’m gutted to be missing.

I finally got round to reading The Power of Positive Deviance, in which management guru Richard Pascale teams up  with the two key practitioners – the Sternins (Jerry and Monique) – to analyse over 20 years of experience in developing the Positive Deviance (PD) approach, building on their pioneering experience working on malnutrition in Vietnam in the early 1990s. Since then, PD approaches have spread and morphed in 50 countries North and South, and been used on everything from reducing gang violence in inner city New Jersey to trying to reducing sex trafficking of girls in rural Indonesia.

with the two key practitioners – the Sternins (Jerry and Monique) – to analyse over 20 years of experience in developing the Positive Deviance (PD) approach, building on their pioneering experience working on malnutrition in Vietnam in the early 1990s. Since then, PD approaches have spread and morphed in 50 countries North and South, and been used on everything from reducing gang violence in inner city New Jersey to trying to reducing sex trafficking of girls in rural Indonesia.

The starting point of PD is to ‘look for outliers who succeed against the odds’ – the families that don’t cut their daughters in Egypt, or the kids that are not malnourished in Vietnam’s poorest villages. On any issue, there is always a distribution of results, and PD involves identifying and investigating the outliers.

But it also matters who is doing the looking. The community must make the discovery itself – it’s no use external ‘experts’ coming in, spotting PD and turning it into a toolkit. Whether it is US hospital staff taking responsibility for tackling MRSA, or poor villagers selling their daughters in Indonesia, this gets round the defensive ‘immune defence response’ that solutions peddled by experts aren’t relevant.

The approach itself – recognizing for any given problem, someone in the community will have already identified a solution – is hugely energizing. Drop out rates in Misiones Province, Argentina were awful, but teachers and principals were initially hostile to being criticism and tried to blame the parents. All that started to change when the facilitators moved from the problem to asking the ‘somersault question’ why were drop out rates much lower in some schools. Teachers then agreed to ask parents to join in, who rapidly identified that the key was teacher attitudes to parents – the positive deviant teachers were negotiating informal annual ‘learning contracts’ with parents. That approach spread and drop out rates in test schools dropped by 50%.

The approach itself – recognizing for any given problem, someone in the community will have already identified a solution – is hugely energizing. Drop out rates in Misiones Province, Argentina were awful, but teachers and principals were initially hostile to being criticism and tried to blame the parents. All that started to change when the facilitators moved from the problem to asking the ‘somersault question’ why were drop out rates much lower in some schools. Teachers then agreed to ask parents to join in, who rapidly identified that the key was teacher attitudes to parents – the positive deviant teachers were negotiating informal annual ‘learning contracts’ with parents. That approach spread and drop out rates in test schools dropped by 50%.

PD means learning to ‘spot the novel in the familiar’ – eg noticing that a mother of an unusually well nourished child dipped the ladle deeper into the family pot and so scooped up solid veg for the kids’ bowls led to a big breakthrough on child nutrition in Bolivia. Families with lower infant mortality in a remote corner of Pakistan put their newborns on a blanket, rather than the bare earth. ‘Footnotes turned out to define the entire plot’.

PD involved huge attention to process –looking at the how, not the what, as in the Bolivian example. What happens next depends on what the authors call ‘social proof’. Rather than experts moving in, recording the PDs and turning them into a powerpoint, communities need to see (and preferably do) for themselves in order to internalize behaviour change.

In all this, experts are often part of the problem: ‘those eking out existence on the margins of society grasp the simple elegance of the PD approach – in contrast to the sceptical consideration of the more educated and/or privileged. Uptake seems in inverse proportion to prosperity, formal authority, years of schooling and degrees hanging on walls.’ Experts have to give up their role as ‘answers looking for problems to solve’ and become facilitators. Not easy. Holding back from providing the answers when you ask a group a question is ‘more difficult than trying to stifle an oncoming sneeze’ (I know that feeling). Some forced themselves to count to 20, by which time someone else has usually answered the question (must try that).

elegance of the PD approach – in contrast to the sceptical consideration of the more educated and/or privileged. Uptake seems in inverse proportion to prosperity, formal authority, years of schooling and degrees hanging on walls.’ Experts have to give up their role as ‘answers looking for problems to solve’ and become facilitators. Not easy. Holding back from providing the answers when you ask a group a question is ‘more difficult than trying to stifle an oncoming sneeze’ (I know that feeling). Some forced themselves to count to 20, by which time someone else has usually answered the question (must try that).

Given this upending of hierarchies, it is not surprising that PD, like other participatory approaches, often leads to cultural and social change, by empowering the lowers to find their own solutions. In corporate and other tight hierarchies PD is often about identifying the parallel processes used by practitioners – the ones they keep hidden from their managers (shades of Ros Eyben’s work on parallel processes in aid agencies).

That may also explain why PD seems to be the last resort, rather than the first one – experts and funders call the Sternins when they’ve tried everything else and it has failed. Otherwise, the ‘Standard Model ‘of identifying gaps, devising initiatives to fill them, and disseminating the guidance is incredibly hard to budge.

Despite its successes, PD, ironically, remains an outlier in the aid business. This is partly because it is slow in scaling up beyond the community – each community has to make the journey of discovery – no shortcuts. Also it typically involves a long slow start – a big consultation to socialize recognition of the problem and ownership, then an inquiry phase in which the community identifies the PDs, then a ‘learning by doing’ phase. That can be difficult for funders, who have neither quick results, or a clear project plan of activities and outputs to comfort them.

Despite its successes, PD, ironically, remains an outlier in the aid business. This is partly because it is slow in scaling up beyond the community – each community has to make the journey of discovery – no shortcuts. Also it typically involves a long slow start – a big consultation to socialize recognition of the problem and ownership, then an inquiry phase in which the community identifies the PDs, then a ‘learning by doing’ phase. That can be difficult for funders, who have neither quick results, or a clear project plan of activities and outputs to comfort them.

What about applying PD in Oxfam or other INGOs? One of messages of book is that tight hierarchies and command and control systems are instinctively hostile to PD. More loosely coupled systems are more likely both to throw up more deviants, and to allow them to be recognized and acted upon.

So within INGOs the best place to start is probably to identify the most independent actors – in the corporate sector, the authors identify sales reps as ideal, since they are typically out there on their own, with enough independence to improvise. The INGO equivalents would probably be country teams, with a combo of a champion in a country director, and staff willing to surrender their expert status and do PD with partners and communities. Any volunteers? Teams already doing it? Could we have made more use of a PD approach, perhaps in the inception phase, in some of the projects I have written about over the years – Chukua Hatua in Tanzania or TAJWSS in Tajikistan?

The book ends with the famous quote from Lao Tzu

‘Learn from the people

Plan with the people

Begin with what they have

Build on what they know

Of the best leaders

When the task is accomplished

The people will remark

We have done it ourselves’

All in all, a hugely engaging read, highly recommended

Here’s Monique Sternin, with a 15m presentation of her work

February 4, 2016

You say you want a Revolution? The Beatles on How Change Happens

Blog break over – did you miss me? Thought not. After a month in writing purdah, I sent off the How Change Happens manuscript to OUP last week, so it is now their problem (for a couple of months at least).

So let’s get restarted with a spot of whimsy. One of the ideas that never made it into the final draft of the book was a critique of the lyrics of the Beatles’ ‘Revolution’. That’s partly because it was written (by John Lennon of course, far too intellectual for Macca) during the tumultuous year of 1968, as a response to the debates on violent v non-violent action, and I thought that would probably be ancient history to most of the book’s intended readership. But it seems a shame to waste it, so here you are:

John Lennon

How Change Happens commentary

You say you want a revolution

Well, you know

We all want to change the world

You tell me that it’s evolution

Well, you know

We all want to change the world

We don’t say ‘revolution’ any more – please replace with ‘transformative change’. Good to see reference to evolution and systems thinking – have you read Beinhocker?

But when you talk about destruction

Don’t you know that you can count me out

You need to rethink: destruction clearly important in terms of economic progress (Schumpeter), and more widely, contestation/conflict often essential aspect of social/political change – ask John Gaventa

Don’t you know it’s gonna be alright

Alright, alright

Spelling? What is the evidence base for this assertion?

You say you got a real solution

Well, you know

We’d all love to see the plan

You ask me for a contribution

Well, you know

We’re all doing what we can

Surely single solutions are implausible, given context specificity? Would certainly be interested in seeing the plan (is it a proper logframe?). ‘Doing what we can’ sounds terribly voluntarist and is only an input – how do you intend to measure results?

But if you want money for people with minds that hate

All I can tell you is brother you have to wait

Wouldn’t constructive engagement stand a better chance of success than a boycott, perhaps a multi-stakeholder initiative round changing ‘hate’ norms?

You say you’ll change the constitution

Well, you know

We all want to change your head

You tell me it’s the institution

Well, you know

You’d better free your mind instead

Changing constitutions is difficult enough, but what about implementation? Changing norms (‘your head’) might be more feasible, but takes decades. In either case, what’s your theory of change?

Norms are themselves an institution (‘rules of the game’) so false distinction in last line

But if you go carrying pictures of Chairman Mao

You ain’t going to make it with anyone anyhow

Baffling non sequitur – please explain

Don’t you know know it’s gonna be alright

Alright, alright

Alright, alright

Alright, alright

Alright, alright

Alright, alright

Positive framing always welcome, but this seems unnecessarily repetitive

And here’s the song. I’m contemplating a new improved How Change Happens version……

And if you like this kind of thing, check out Bob Marley on the food price crisis

January 31, 2016

Links I Liked

Happy Monday morning everyone. Here’s Dilbert on meetings

Busy week for tax geeks:

A Eurodad analysis of the European Commission’s Anti-Tax Avoidance Package

IDS tax guru Mick Moore on the links between the flawed new OECD tax agreement on TNCs, aka the BEPS (Base Erosion and Profit Shifting) recommendations and the Google (non) tax scandal?

Although Maya Forstater doesn’t think the UK’s Google tax deal is that bad (not sure many people agree with her, tho)

Why taxing global companies is hard (when sales, employment & costs are all in different countries). Excellent  backgrounder from Owen Barder owen.org/blog/8532

backgrounder from Owen Barder owen.org/blog/8532

Meanwhile, in the world beyond tax:

Jobs in poorest countries are the most vulnerable to automation argues a new Oxford Martin School paper [h/t Laurence Chandy]

What’s on the international agenda in 2016? A lot of meetings, apparently.

For academics who still need convincing: how to write a blogpost from your journal article in eleven easy steps.

And finally, entirely off topic but we need something to cheer us up at this time of year. What happens when the teacher tells a 5 year old to sing out loud in the school play? (Apparently she’s all grown up now and unscarred by the event) [h/t Michelle Mularkey]

January 24, 2016

Links I Liked

Still in writing purdah (going well thanks), but unable to stay away from social media altogether – here’s a few links from last week’s twitter stream.

Smart headline from NY Post (at least the Panda in Washington zoo appreciated the weather) [h/t Chris Blattman]

Overview of state of women’s empowerment in Africa from Brookings

Oxfam did its Davos thing again, with the annual killer fact fest on extreme wealth (the key number is 62)

And its in house geeks fended off the equally predictable (and weak) attacks on its numbers

And its in house geeks fended off the equally predictable (and weak) attacks on its numbers

Or you could just take the Guardian global inequality quiz. I got 9/10 (damn that 4th C Greek Bishop!)

Seven ways technology has changed us. Martin Wolf at his brilliant best

Stop! Before you schedule that meeting, why not work out how much it is going to cost with this handy calculator? Brilliant, but only adds up salaries of those present, not opportunity costs, loss of will to live, existential crises etc

Some predictions are better than others: Nikola Tesla in 1926, describing today’s world [h/t Vala Afshar]

What makes an academic paper useful for health policy? Sound advice from former DFID research boss

Wonderful. Some high street businesses in Crickhowell, a small Welsh town, decide to go offshore – if big TNCs can avoid tax, so can they – starting a fair tax town movement that should get the British government worried

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers