Duncan Green's Blog, page 147

March 10, 2016

Why we need to rethink how we measure inequality – please welcome the Absolute Palma index

Oxfam’s Nick Galasso (left) and ODI’s Chris Hoy (right), author of a new paper on the topic, argue

Oxfam’s Nick Galasso (left) and ODI’s Chris Hoy (right), author of a new paper on the topic, argue for a rethink on inequality metrics

for a rethink on inequality metrics

The world is abuzz about inequality

Pope Francis famously tweeted that inequality is the root of evil.

As we witnessed in Davos in January, the media can’t get enough of Oxfam’s statistic that the richest 85, 80, 62 people have the same wealth as the poorest half of the planet.

In 2014, a 700-page book on inequality by a French academic was a worldwide best seller.

But what exactly is this inequality everyone is talking about? It turns out that we might be measuring it all wrong. The Gini coefficient and (increasingly) the Palma Index are the most popular tools for measuring inequality within a country. These indicators calculate the ratio of the incomes of the rich over the poor. For instance, the Palma is a score calculated by dividing the share of income of the richest 10% by that of the poorest 40%.

The problem with these approaches is that they only measure relative inequality. If the incomes of the poor grow as fast as those of the rich, these measures will stay the same over time, but the difference in income from a one percent growth for the poor versus a one percent growth for someone already rich can be significant. As the Italian demographer, Livi Bacci, said ‘it is not much of a relief for somebody living on $1 day to see that his income, up by three cents, is growing as much as the income of the richest quintile’.

fast as those of the rich, these measures will stay the same over time, but the difference in income from a one percent growth for the poor versus a one percent growth for someone already rich can be significant. As the Italian demographer, Livi Bacci, said ‘it is not much of a relief for somebody living on $1 day to see that his income, up by three cents, is growing as much as the income of the richest quintile’.

Unfortunately, relative inequality measures don’t tell us about the absolute gap in incomes between the rich and the poor.

Exploring the difference between relative versus absolute inequality

To explore the differences between absolute and relative inequality consider the example of the Philippines (see figure).

Over the last 25 years, relative inequality remained fairly stable in the country. This can be seen by the fact that the red line is quite flat across the income distribution as on average all people have experienced a growth rate in their incomes of around 2% a year. However, the green line shows that the additional income generated from this growth is massively weighted towards the rich end of the income distribution – they got the lion’s share of the dollars, a fact obscured if we stick to measures of relative inequality.

In other words, absolute inequality increased dramatically.

[Note: The slower average income growth for the top percentiles is largely due to the very richest people in the Philippines suffering considerable loss in incomes during the 2008 financial crisis.]

Why does this matter?

Politicians, pundits, and other voices often herald the impressive economic growth of developing countries in recent decades as a sign that the end of poverty and extreme inequality is near. And, in many countries relative inequality indicators are suggesting the poor are catching up with the rich.

For instance, using a relative inequality measure the World Bank boldly concluded that an era of shared prosperity is already upon us. According to its Global Monitoring Report, the poorest 40 percent fared better than the average in 58 of 86 countries. Yet, a recent paper shows that while the income of the poor may have grown faster, in a number of these countries they captured a smaller share of new income from growth compared to the richest 10 percent.

Even more shocking, a recent ODI paper shows that in the past 30 years absolute inequality always increased when countries experienced long periods of growth across income groups.

The insights gleaned from comparing relative versus absolute inequality tell us that growth needs to be even more intensively pro-poor than often suggested. In fact, closing the gap between the rich and poor requires the bottom 40 percent to grow around twice the country average.

A new measure of the gap between the rich and poor

Measuring how the gap between the rich and poor changes over time is an essential first step in addressing

Credit: Paul Smith, Panos

inequality. The ODI paper proposes a new measure called the ‘Absolute’ Palma, which is the average income of the top 10 percent minus the average of the bottom 40 percent.

This is a modification of the Palma ratio that was first proposed on this blog. As mentioned above, the Palma is a relative measure, calculating the ratio of the share of income of the top 10% to that of the bottom 40%. In contrast, the ‘Absolute Palma’ captures what this means in terms of the actual income gap between the top 10% and bottom 40%.

People scoffed at the initial proposal for the Palma ratio, (which was a big improvement on the Gini), but it has caught on rapidly. We think an Absolute Palma would be an even better measure of inequality – let’s hope it catches on just as quickly.

March 9, 2016

Book Review: What can Activists learn from the AIDS Drugs Movement?

Still catching up with reviews from my holiday reading – Alex de Waal’s new book (already reviewed) and AIDS  Drugs for All, which came highly recommended. (I also read and enjoyed Marlon James and Elena Ferrante – I’m not completely sad/obsessive, honest.)

Drugs for All, which came highly recommended. (I also read and enjoyed Marlon James and Elena Ferrante – I’m not completely sad/obsessive, honest.)

AIDS Drugs for All is a forensic account of ‘a heroic effort on the part of social activists, policy entrepreneurs and sympathetic corporate executives’. Between them ‘the AIDS treatment movement was able to catalyze a profound transformation in the market for antiretroviral (ARV) medicines at the turn of the millennium, from one whose business model was ‘high price, low volume’ to one characterized by ‘universal access.’’ Conceptually they were able to change the definition of ARVs from private good to something closer to a ‘merit good’ whose price should be determined by need, not supply and demand.

The ambition of that ‘market transformation’ was stunning: ‘On the demand side, stakeholders had to change their perception of whether ARVs would work in the developing world, while on the supply side changes had to be made regarding pharmaceutical patents, pricing and competition. This change in the market needed to be supported by institutions that made these changes credible, in particular, institutions that would ensure that funds would be made available for the purchase and uptake of high-quality ARV medications at the reduced prices.’

The authors identify multiple success factors – the universality of a message about ‘bodily harm’; the turbulent state of Big Pharma in the late 90s and early 2000s, with big-earning pipeline drugs running out and new challenges from biotech and generics (off patent) manufacturers in India and elsewhere.

The authors identify multiple success factors – the universality of a message about ‘bodily harm’; the turbulent state of Big Pharma in the late 90s and early 2000s, with big-earning pipeline drugs running out and new challenges from biotech and generics (off patent) manufacturers in India and elsewhere.

Activists also found an obscure, but in the end vital, forum to raise these issues on the global level – the WTO discussions on ‘trade-related intellectual property rights’ (TRIPs). This led to a big fight on whether and when poor countries should be ‘allowed’ to waive patent rules during health emergencies such as the HIV pandemic in order to get life-saving medicines at affordable prices. This all reached a peak at the 2001 WTO ministerial that launched the Doha round – I was there, but working on agriculture.

They won. According to the authors, ‘no matter which side of the patent debate one falls on, most observers would agree that the WTO decision of 2001 helped solidify the confidence of developing countries to pursue strategies that defended public health.’

The effectiveness of the activists was in no small measure down to the power of networks – enabled by the rise of  ICT and some star policy entrepreneurs such as Jamie Love. Oxfam and MSF were also key players. I remember in Doha being baffled by the arcane arguments of the TRIPs lobbyists, but very impressed by their energy and organization.

ICT and some star policy entrepreneurs such as Jamie Love. Oxfam and MSF were also key players. I remember in Doha being baffled by the arcane arguments of the TRIPs lobbyists, but very impressed by their energy and organization.

But success also depended on an often under-rated factor – the stupidity of the enemy. Campaigning 101 says you need a problem, a solution and a villain. Step forward Big Pharma, which in 1998 decided to sue the South African government for breaking patent rules on HIV medicines. As the Wall Street Journal rhetorically asked ‘Can the pharmaceuticals industry inflict any more damage upon its ailing image? Well how about suing Nelson Mandela?’

The ensuing PR disaster led to the case being withdrawn in 2001, but by then it had spurred the creation of South Africa’s Treatment Action Campaign, catalysed the global AIDS movement and become an issue in the US election campaign in 2000.

So much for the historical account, what about the broader conclusions? The authors distil 5 generalizable success factors for activists wishing to pursue similar market transformations in other drugs-related areas, food and agriculture, extractives or finance.

So much for the historical account, what about the broader conclusions? The authors distil 5 generalizable success factors for activists wishing to pursue similar market transformations in other drugs-related areas, food and agriculture, extractives or finance.

A highly contestable market. If a few companies have it all sewn up, they are less likely to listen, but if there are genuine threats from insurgents, they will either enter the market, or the threat of entry will force the incumbents to change. The authors suggest a spate of mergers and acquisitions is a good indicator of a sector in turmoil and ripe for campaigns of this type.

A compelling frame: narrative matters – in this case ‘drugs companies are killing people by denying them access to medicines’ was almost impossible to resist.

A coherent ask. The AIDS movement eventually settled on access to treatment as its big ask, but only after a difficult discussion on whether it should give priority to prevention (that issue hasn’t gone away).

Low/favourable costs. The involvement of generics producers was crucial in driving costs, as was the fact that Big Pharma was already experimenting with ‘differential pricing’ between different markets.

Stabilizing institutions. This was (for me) the most striking factor – by getting agreement to set up multi-billion dollar institutions such as the Global Fund, PEPFAR and UNITAID (funded by the world’s first global tax, on airline fares), the movement created institutions that would carry the work forward after the spike of mobilization faded (as it always does).

It’s a thought-provoking list, but I think it misses a lot of what matters in practice: the need for  legitimacy/authenticity of advocates (the fact that TAC and other activist groups were organized by people living with AIDS was crucial); the importance of critical junctures, such as the South African court case or the Doha ministerial; luck; stupidity (South Africa again); broader normative shifts on rights, women etc that often underpin specific changes to policies and institutions. I would have liked to hear their views on the differences between anti- or pro- campaigns.

legitimacy/authenticity of advocates (the fact that TAC and other activist groups were organized by people living with AIDS was crucial); the importance of critical junctures, such as the South African court case or the Doha ministerial; luck; stupidity (South Africa again); broader normative shifts on rights, women etc that often underpin specific changes to policies and institutions. I would have liked to hear their views on the differences between anti- or pro- campaigns.

The authors end by applying their conclusions to a bunch of other potential change campaigns – from maternal mortality to malaria to climate change, and back test against the movement for the abolition of slavery. Nice idea but they cast the net far too wide – big systemic shifts like tackling climate change are most unlikely to have the same logic as a specific campaign such as access to medicines. As a result, the comparison is a bit vague and inconclusive.

Final criticism: these ‘success conditions’ reveal a deep preference for market-based solutions. There is little discussion of moral or justice arguments for change, or straightforward legislation to stop bad stuff – I fear in the case of anti-slavery the authors would have ended up proposing subsidies for more comfortable slave ships.

But putting aside the overstretch, corporate campaigners will find a lot of food for thought here – highly recommended.

March 8, 2016

Links I Liked

Bit of a delay this week, but here’s last week’s pick of the  interwebs

interwebs

In the class riddled UK, even the pop stars are disproportionately privately educated

DFID’s Pete Vowles has some useful advice for anyone pursuing change in large organizations

Following last year’s World Development Report on behavioural economics, the World Bank sets up a ‘nudge unit’. The Global Insights Initiative (Gini) will run experiments to promote improvements in nutrition, sanitation etc

New Report: Indigenous Peoples & local communities own just 1/5 of their land

In Tanzania, reality TV does women farmers – meet the Female Food Heroes

Time for some Election stuff:

In the US, making history is guaranteed (sort of)…..

How women, the Green Movement and a secure comms app from Russia shaped Iran’s elections

Got 20 minutes? If you haven’t seen it already, revel in this John Oliver take down of the Donald

March 7, 2016

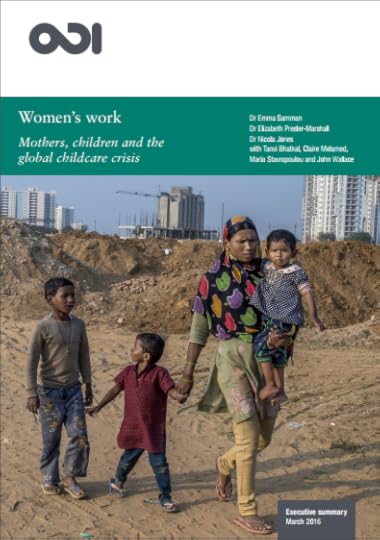

Time Poverty and The World’s Childcare Crisis – good new report for International Women’s Day

My colleague Thalia Kidder is a feminist economist who’s been working for years to try and get the ‘care economy’

onto the development agenda. It’s been frustrating at times, but she should be celebrating right now: Oxfam’s bought in with projects that include developing a ‘rapid care analysis’ assessment tool; Melinda Gates decided to highlight Time Poverty in the Gates’ annual letter, and now for International Women’s Day, ODI has published an excellent report on the ‘hidden crisis in childcare’.

Some highlights:

Mothers are entering the workforce in increasing numbers, both out of choice and necessity. But this has costs. In trying to meet the twin demands of caring for their children and providing for them economically, women’s capacity is being stretched to the limit. The critical issue is time, which comes at a price – in health, in wellbeing and in money.

There are 671 million children under five in the world today. Given labour force participation rates that exceed 60% globally, a large number of these children need some sort of non-parental care during the day. Early childhood care and education programming is not managing to match this need. At most, half of three- to five-year-old children in developing countries participate in some form of early childhood education, typically for a few hours daily.

We know very little about what is happening to the rest, but all the evidence points to a crisis of care. That crisis is heavily concentrated among the poorest children with the most restricted access to early childhood support. Across the world, at least 35.5 million children under the age of five are being left alone, or with other young children, without adult supervision.

Across 66 countries around the world representing two-thirds of the global population, there are huge inequalities in the time spent by women and men on unpaid work. On average, women spend 3.3 times as much as men do.

The School Run, Hanoi credit: Ed Yourdon

Unpaid care responsibilities cost women more than ‘just’ time – they are also reflected in lower income. The ‘motherhood pay penalty’, whereby mothers earn less than childless women, has been estimated at 37% in China, 42% in 31 developing countries and 21% in the UK. In part due to women’s choices, and in part the result of employer discrimination, the pay gap also reflects the absence of accessible childcare.

The cost of unpaid care has been valued recently at up to $10 trillion annually, around 13% of world GDP. It is not just mothers bearing this cost. This unpaid care is also borne by adolescent and even younger girls, passing on the costs to the next generation in the form of lost chances for schooling. Evidence from parts of Ethiopia suggests that 52% of rural girls between five and eight years old are engaged in care work compared to 38% of rural boys – and that one-quarter (26%) of these girls spend three or more hours daily on unpaid care.

Policy Implications

Too often the assumption is that managing time is only a problem when women are working in formal sector jobs, which means that the focus is on labour market provisions that give parents the right to take time off, protect breastfeeding and provide crèches. These are important for those women who can benefit from them. But such policies cannot help with the daily struggle faced by the vast majority of women in the developing world working in the informal sector.

In India, for example, less than 1% of women receive paid maternity leave. A focus on labour market policy alone is  therefore myopic. Two additional policy areas are important – social protection and early childhood care and education (ECCE). Social protection programmes are often a crucial support – but do not generally help to alleviate the time constraints faced by so many women. Nurseries and other care programmes benefit young children and appear to be valued by caregivers. However, existing programmes are centred almost entirely around the needs of small children and a focus on school readiness, rather than the needs of their carers.

therefore myopic. Two additional policy areas are important – social protection and early childhood care and education (ECCE). Social protection programmes are often a crucial support – but do not generally help to alleviate the time constraints faced by so many women. Nurseries and other care programmes benefit young children and appear to be valued by caregivers. However, existing programmes are centred almost entirely around the needs of small children and a focus on school readiness, rather than the needs of their carers.

Some positive examples:

Encouragingly, some countries are successfully responding to these challenges. Vietnam, for example, despite being a Lower Middle Income Country (LMIC), has in place a full array of labour market policies supporting care – including six months of maternity leave at 100% pay, paid paternity leave and paid breaks for both antenatal care and breastfeeding. Companies with large female workforces are also required to provide on-site crèche care or to subsidise private provision. South Africa, in turn, is one of only two developing countries outside Latin America and the Caribbean to ratify the International Labour Organisation Convention (ILO) on Domestic Workers (No. 189). Additionally, the country has put in place a number of creative policies to support children, with a premium on care – among these are the Older Persons Grant, which recognises the role of many grandparents in childraising, the child support grant and a disability grant focused on the needs of caregivers of children with disabilities.

And the inevitable ODI infographic:

March 6, 2016

Choosing the How Change Happens book cover round two: one more vote, please

OK, so we had a clear winner on the first vote – the ripped paper one got 66% of the 500 or so votes and my LSE students agreed. But a sizeable number of comments said ‘none of the above’, so I went back to OUP and we had a think. Some people wanted a cartoon – too NGO-y in my view. Some people wanted a photo – Arab Spring, Mandela walking to freedom etc, but OUP said that makes it look like an academic textbook (and they should know). So OUP came up with some more typographical options and this will be the last vote, honest. So please vote between these 3 options

the ripped paper

placard

red speech boxes

Over to you:

Note: There is a poll embedded within this post, please visit the site to participate in this post's poll.

March 3, 2016

From Sweatshops to Switzerland, the women in Myanmar behind the billionaires’ fortunes

Max Lawson, Oxfam’s Head of Global Campaigns reflects on a recent visit

The young garment factory workers share a tiny room in a wooden shack, spotlessly clean, with pictures of Myanmar pop stars beside a photo of their parents back in the village. But there is no escaping the smell of the open drain outside. The three sisters and their cousin all work in factories making clothes for export to the UK, United States and other countries for household brands such as GAP, Primark, H&M and Tesco. They belong to a labour rights group working with Oxfam to fight for better conditions for workers, and we are there to hear about their experiences on the factory floor. Myanmar’s garment sector is expanding fast, now employing around 300,000 people – 90% female and mostly under-25.

Daily average wages of $2.80 are not enough to survive on. Oxfam’s recent survey found that almost half of garment workers are trapped in debt and have to borrow money to meet basic needs like food, medicine and transport. They work up to 11 hours a day, six days a week, rarely receiving sick pay despite this being a legal requirement. Many reported working into the night to meet impossible production targets, on one occasion sewing until 6.30am before restarting at 7.30am every day for a week. Safety was a big concern, with one in three reporting a workplace injury and many afraid of factory fires because of blocked exits.

In the week we visited Myanmar, Oxfam’s report ‘An Economy for the 1%’ caused a stir at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, revealing that 62 billionaires now own the same wealth as the poorest half of the world. The report shows that the global economic system is skewed in favour of the top 1%, who have seen half of the total increase in global wealth in the past 15 years, while the bottom 50% have had to make do with just 1%.

In the week we visited Myanmar, Oxfam’s report ‘An Economy for the 1%’ caused a stir at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, revealing that 62 billionaires now own the same wealth as the poorest half of the world. The report shows that the global economic system is skewed in favour of the top 1%, who have seen half of the total increase in global wealth in the past 15 years, while the bottom 50% have had to make do with just 1%.

Interestingly four of the world’s 62 richest billionaires made their fortunes in high-street fashion. Amancio Ortega of Spain, worth $64 billion, heads garment giant Inditex, owner of Zara. Swede Stefan Persson, worth $24 billion, is chairman of H&M and a 28% stakeholder. Tadashi Yanai of Japan owns Uniqlo and is worth $20 billion. The fourth is Phil Knight, who until June 2015 had spent 51 years as chairman of Nike, and is worth $21 billion.

H&M buys from factories in Myanmar and Uniqlo is considering doing so. Inditex pioneered the model of shorter supply chains and reduced lead times, now the norm in fast fashion. But this business practice puts huge pressure on suppliers and their workers, leading to forced overtime and pressure to squeeze wages as low as possible.

H & M does at least publish which factories produce its clothes in Myanmar. Many big brands refuse to even do this. As one of my colleagues put it, ‘Can you think of one good reason why a high street brand would want to hide where its clothes are made?’ Both H&M and Inditex have taken steps to address poverty wages, for instance by signing an agreement with global union IndustriALL to promote sector bargaining. However, between 2001 and 2011 wages for garment workers in most of the top 15 apparel-exporting countries fell in real terms.

Some commentators have accused Oxfam of being anti capitalist for throwing rocks at an economic system than has

credit: Kate Peters

helped to reduce global poverty. It is of course true that real progress has been made. The young women we met now earn more than the extreme poverty line of $1.90 a day, so are no longer officially counted as poor. But is that really good enough?

Oxfam recognises the power of capitalism to transform people’s lives – but we believe the current warped ‘market fundamentalist’ model, as the Bank of England Governor calls it, is failing us all. Matthew Paris, a former Conservative MP writing about our Davos report in The Times newspaper, put it best when he said that listening to those trying to defend today’s capitalist system reminded him of Communists trying to defend the USSR: ‘How much longer, then, can we market liberals shrug off huge failures in the working examples we have of capitalism?… If the free market is to be defended in the new century, these inequities are no longer something from which the centre-right can turn away.’

Throughout our history, the majority of those who fought to stop children having to go to work, or for a ten hour working day, or for a weekend, or paid holiday, sick pay and above all for wages which allow ordinary women and men to live a decent life were not anti-capitalists. They just believed we could do better. Activists of the past were dismissed as naive or seditious or both, but what they fought for we now see as being a part of a civilised society.

Credit: Kate Peters

Today we have to continue that fight. We need to make capitalism work for the majority rather than the top 1%. This can be done. For example, a critical mass of companies could commit to source from countries with good labour regulation, adapt their business practices so factories can afford to pay a living wage and ensure workers are free to negotiate with management.

We have the talent, technology and imagination to build a more human economy – one where we have not just minimum wages, but maximum ones too. Where we see an end to this extreme wealth that benefits no one but a tiny elite.

When I met those young women in Myanmar learning about their rights, and the successful struggles of other garment workers in Thailand and Cambodia, I was filled with hope for the future. For a better, fairer, future they will fight for. I know I want to do all I can to help them.

March 2, 2016

Just Give them the Money: why are cash transfers only 6% of humanitarian aid?

Guest post from ODI’s Paul Harvey

Giving people cash in emergencies makes sense and more of it is starting to happen. A recent high level panel report found that cash should radically disrupt the humanitarian system and that it’s use should grow dramatically from the current guesstimate of 6% of humanitarian spend. And the Secretary General’s report for the World Humanitarian Summit calls for using ‘cash-based programming as the preferred and default method of support’.

But 6% is much less than it should be. Given the strong case for cash transfers, what’s the hold-up in getting to 30%, 50% or even 70%? The hold-up isn’t the strength of the evidence, which is increasingly clear and compelling. Cash transfers are among the most rigorously evaluated and researched humanitarian tools of the last decade. In most contexts, humanitarian cash transfers can be provided to people safely, efficiently and accountably. People spend cash sensibly: they are not likely to spend it anti-socially (for example, on alcohol) and cash is no more prone to diversion than in-kind assistance. Local markets from Somalia to the Philippines have responded to cash injections without causing inflation (a concern often raised by cash transfer sceptics). Cash supports livelihoods by enabling investment and builds markets through increasing demand for goods and services. And with the growth of digital payments systems, cash can be delivered in increasingly affordable, secure and transparent ways.

People usually prefer receiving cash because it gives them greater choice and control over how best to meet their own needs, and a greater sense of dignity. And if people receive in-kind aid that doesn’t reflect their priorities they often have to sell it to buy what they really need as, for example, 70% of Syrian refugees in Iraq have done. The difference in what they can sell food or other goods for and what it costs to provide is a pure waste of limited resources. Unsurprisingly people are better than aid agencies at deciding what they most need.

There are over 100,000 Eritrean refugees in Ethiopia, many of them youngsters seeking a better life. The European Commission’s Humanitarian aid and Civil Protection department (ECHO) finances basic services such as shelter, food a small cash stipend, access to clean water, latrines and hygiene services as well as child protection activities. Photo credit: EU/ECHO/Malini Morzaria

It’s taken a long time for the international aid system to accept and embrace the use of cash because it challenges all sorts of deep seated attitudes about how best to help people and how the system is structured. The aid sector in general is bad at trusting people and reluctant to hand-over power and control. It’s fundamentally premised on the idea of the external experts deciding what is needed and providing it. Cash challenges that and so creates a series of professional insecurities. What will happen to logisticians and food aid professionals? And if it makes sense to deliver one cash grant to meet a range of basic needs, do we need so many organisations focused on delivering humanitarian assistance? In Lebanon in 2014, 30 aid agencies provided cash transfers and vouchers for 14 different objectives such as winterisation, legal assistance and food. It’s the very simplicity of cash that is threatening to current models for delivering and financing humanitarian assistance.

So what will humanitarian action look like in 2030 and will aid agencies have embraced the disruptive potential of cash to dramatically change how humanitarian action happens?

Being an optimistic soul I think we’ll have made some serious progress on SDG goal 1 on ending poverty. Richer people and wealthier states will be more resilient in the face of growing numbers of climate change-related natural disasters and investing more in being prepared for them. Progress on SDG 1 will have in part been achieved by a huge expansion in social assistance programmes. So, more of the world will look like 2015 in northern Kenya where, in response to drought and floods, the Kenya Hunger Safety Net has been able to automatically expand payments to more of the population because it had pre-registered everyone and had defined triggers for expanding the programme.

Across most of the world international humanitarian actors won’t be focussed on delivering assistance (whether cash  or in-kind). They’ll be supporting the non-governmental action of southern civil society which will be lobbying their own governments to include those wrongly excluded from government-run cash assistance and engaged in the sort of voluntary responses and advocacy we’ve seen in response to recent floods in the UK.

or in-kind). They’ll be supporting the non-governmental action of southern civil society which will be lobbying their own governments to include those wrongly excluded from government-run cash assistance and engaged in the sort of voluntary responses and advocacy we’ve seen in response to recent floods in the UK.

International humanitarian action will be much more narrowly focussed on conflicts. The wars in Syria, CAR and Yemen will tragically be entering their third decade. Rolling five year funding windows will at last have allowed aid agencies to move from annual appeals to longer-term responses to long-running wars. At the core of these five year plans will be a basic income grant provided to all those registered as having war disrupted livelihoods. In each context, delivery of the basic income grant will be competitively tendered and generally won by consortia of local and international payment companies, UN agencies, the Red Cross and local and international NGOs. They’ll be hitting and usually exceeding a benchmark of getting 75 cents of every dollar directly onto disaster affected peoples’ payment cards.

Of course, some natural disasters will still overwhelm local and national capacities, leading to appeals for international help, and new wars will generate humanitarian needs. Cash-based responses will be at the core of rapid humanitarian responses with better contingency planning and preparedness in partnership with the private sector enabling payments to start within days of the onset of a crisis.

Freed from the constraints of delivery, organisations will have had to focus much harder on where and how they add value to humanitarian action. Some such as Oxfam with its specialism in water and sanitation will have re-focussed on  technical expertise. Others will disappear, shrink radically or move to supporting southern organisational networks without directly implementing. There will be a much greater focus on assessment, analysis, targeting and monitoring. Deciding what’s needed, who should get it, how much they should get and whether or not the right people are getting it is where the really difficult challenges of humanitarian action have always been and will remain.

technical expertise. Others will disappear, shrink radically or move to supporting southern organisational networks without directly implementing. There will be a much greater focus on assessment, analysis, targeting and monitoring. Deciding what’s needed, who should get it, how much they should get and whether or not the right people are getting it is where the really difficult challenges of humanitarian action have always been and will remain.

And they’ll be much more of a focus on the social and political dimensions of humanitarian crises. Aid agencies have tended to focus on being deliverers of stuff – a humanitarian version of DHL. That mind-set will have shifted to being more like social workers – working with local people and local organisations to better understand how to help them deal with the traumas and consequences of conflict. That will involve more negotiation and advocacy with parties to the conflict and on the mental health impacts of war and more of a brokering and facilitating local solutions approach in line with current thinking about how to do development differently. The question humanitarian organisations ask will have shifted from ‘what do we need to deliver?’ to ‘how can we help people to maintain their dignity and live safely in the midst of conflict? ‘

Giving people cash still won’t always be the best option. Sometimes markets will be too weak for people to be able to buy what they need and sometimes government policies will make it impossible to provide cash. Cash transfers will still need to be complemented by the provision of public goods that markets will not provide efficiently, such as clean water, sanitation or immunisation. The use of cash transfers does not mean that humanitarian actors will give up their key roles of proximity, presence and bearing witness to the suffering of crisis-affected populations. It’s the spirit of solidarity in the face of unacceptable suffering that will remain core to humanitarian action and that better use of cash will enable a greater focus on.

March 1, 2016

The art of delivery – lessons from working with African governments

Dan Hymowitz

(@dhymowit), Acting Director of Development and External Relations for the Africa Governance  Initiative (AGI), reflects on what they’re learning about the development trend of ‘delivery’.

Initiative (AGI), reflects on what they’re learning about the development trend of ‘delivery’.

I remember the first time I started to think seriously about delivery: it was just over five years ago sitting in a conference room in Liberia. At the time, I was working with the Liberian Presidency and was in a meeting with former British Prime Minister Tony Blair who was exploring whether his nascent initiative – which later became the Africa Governance Initiative (AGI) – could usefully support President Sirleaf’s team.

I had expected the agenda to cover big themes: plugging infrastructure gaps, creating thousands of jobs or perhaps unlocking growth in the cocoa or rubber industries. Instead one of the most recognisable political leaders of the 20th century attempted to convince us that diary management was a critical aspect of Liberia’s future development. I won’t lie. It felt a little mundane.

Once I got past the anti-climax his point began to resonate with me. What if President Sirleaf’s diary were a just bit more efficient and tightly focused on her priorities? Wouldn’t that mean more helpful pressure on, and support to, the relevant ministers? What if her team managed the overwhelming flow of paperwork to her desk better? This could mean freeing up her time to focus on big picture reforms in education or energy.

I was also struck by how different this starting point was from a lot of other international development programmes; too often more preoccupied with minimising a leader’s ability to do harm than maximising their ability to do good. I didn’t know it then, but two-plus years later I would end up joining AGI where recently I’ve been working on the first article in our ‘art of delivery’ series: reflections from AGI’s experience working with governments in ten African countries since 2008.

I’ve learned a lot in that time and so has AGI. For example, early on we probably did focus too much on delivery units as the mechanism to drive results from the centre of government. These units sit at the heart of government tracking progress on leaders’ priorities and intervening to solve implementation problems. But we’ve seen that such units aren’t always the answer and that it’s better to consider a toolbox of potential delivery approaches – from performance contracts to stocktakes to positive incentives for high-performing ministers.

I’ve learned a lot in that time and so has AGI. For example, early on we probably did focus too much on delivery units as the mechanism to drive results from the centre of government. These units sit at the heart of government tracking progress on leaders’ priorities and intervening to solve implementation problems. But we’ve seen that such units aren’t always the answer and that it’s better to consider a toolbox of potential delivery approaches – from performance contracts to stocktakes to positive incentives for high-performing ministers.

So why write about delivery now? Because delivery – supporting political leaders to bridge the gap between their visions and implementation of reforms that make a difference in citizens’ lives – is at the heart of what AGI does. And while just a few years ago we sometimes felt we were some of the only ones talking about this, that’s no longer the case. Today there’s a proliferation of delivery units and mechanisms around the world – 15 at the national level in 6 continents – and countless other similar bodies with slightly different names.

The series is called the ‘art of delivery’ because we want to bring together two strands of thinking that seem separated at the moment: ‘delivery’ and ‘doing development differently’. On delivery, as we discuss in our first paper, while the emerging interest in implementation and results is a welcome development trend, some of the current literature and thinking is too focused on technical aspects of delivery like performance monitoring and setting up delivery units. These things are important. But the risk is leaving out areas the doing development differently  movement emphasises like adapting approaches to the local context and navigating politics. For example, in one country we’ve worked in, delivery unit staff didn’t feel they had the authority to challenge ministers because the unit didn’t have the full backing of the President. The result was a body that went through the motions of ‘monitoring’ progress without any real teeth. Figuring out how to fix this is more art than science.

movement emphasises like adapting approaches to the local context and navigating politics. For example, in one country we’ve worked in, delivery unit staff didn’t feel they had the authority to challenge ministers because the unit didn’t have the full backing of the President. The result was a body that went through the motions of ‘monitoring’ progress without any real teeth. Figuring out how to fix this is more art than science.

In our series we look at common mistakes or dysfunctions that we’re seeing in delivery work. The first article focuses on how many in development underemphasize the political aspects of delivery such as harnessing the use of power and incentives. Our second piece will examine how when you try to fix everything, nothing gets done. Prioritization is a pre-requisite for successful delivery but for many reasons – including that it’s hard to stick to – it’s usually not done well. Our third piece gets into how international partners can get fixated on form over function in delivery and are not willing enough to adapt delivery systems to evolving challenges. And finally, we’ll look at something international partners too often forget when supporting delivery: that ‘how matters’ and that if your staff don’t work with governments in ways that build genuine trust, the delivery systems you’re supporting won’t work.

These days our team in Liberia is focused on the bigger issues. In fact we are now looking at how to unlock growth in the cocoa and rubber industries. In the intervening years we’ve tried lots of ways to support delivery in Liberia – some more successful than others. President Sirleaf now has less than two years left in office. If her ambitious agenda to build roads, expand electricity and improve schools is to succeed, then her schedule will continue to matter as much as her strategy.

February 29, 2016

Book Review: Alex de Waal, the Real Politics of the Horn of Africa

There’s a balance to be struck in writing any non-fiction book. Narrative v information. How often do you return to  the overarching storyline, the message of the book, the thing you want the reader to take away? How much information – facts, names, dates, events – do you include? Too much storyline, and the book feels flimsy. Too much information and the reader gets lost in the detail.

the overarching storyline, the message of the book, the thing you want the reader to take away? How much information – facts, names, dates, events – do you include? Too much storyline, and the book feels flimsy. Too much information and the reader gets lost in the detail.

Alex de Waal struggles with this in The Real Politics of the Horn of Africa, not least because he knows so much – for decades he’s been both observer and participant in what he calls ‘the Horn of Africa’s cornucopia of violence and destruction’; he’s been in the room during the big peace talks, interviewing and befriending the region’s Big Men. The result is indigestible but brilliant. I read the overview sections, but skipped the case study chapters (Darfur, Sudan, South Sudan, Somalia, Somaliland, Eritrea and Ethiopia) – hey, I was on holiday…… Anyone who knows the Horn will get a huge amount from reading it.

The overall message is a powerful one – the category of ‘fragile and conflict affected states’ is largely useless, a description of what is missing to the eyes of a traditional Western view of development (institutions, stability, rule of law) not what is actually going on – how decisions are made, the ‘political circuitry’, and accumulation and loss of power, the use of violence.

De Waal’s unblinking gaze seeks to describe that reality, warts and all. His big idea is that politics in the Horn is best understood as a marketplace, where the currency is money and violence. ‘States’ are largely imaginary constructs. What matters in politics is accumulating as large a ‘political budget’ as possible – the discretionary funds that any leader can spend on buying support, both in votes and guns. In contrast, ‘the public budget is a sideshow’. In the hierarchy of the political marketplace, everyone is both a buyer of smaller players, and a seller to bigger ones. ‘Violence is a means of bargaining and signalling value within the marketplace.’

The political marketplace is not some dwindling vestige of patronage politics, quietly making way for democracies of political parties and programmes. Quite the opposite – ‘political markets are becoming dominant while state-building fades’. Whatever their instincts, leaders either have to play by the rules of the political marketplace, or be cast out. ‘Most members of the political elites of north-east Africa have come to resemble gangsters rather than civic political leaders.’ Along the way, state boundaries have largely dissolved as political entrepreneurs compete across the region in a form of brutal Darwinism.

South Sudan: the political marketplace in action

De Waal argues that political marketplace systems arise where four conditions exist: political finance is in the hands of individuals; control over violence is dispersed or contested; political disputes are not resolved by institutions like the Law and the countries are integrated into the global political and economic order in a subordinate position.

He stretches the marketplace analogy as far as it will go, and then some, analysing the actions of violent warlords as entrepreneurs, suppliers, buyers, producers of goods and services.

How did this happen? Here’s where de Waal’s encyclopaedic knowledge of the region really shows, a masterly synthesis of a sequence of events that destroyed the ‘modernizing project’ of building states in the region: economic crisis and the retreat of the state in the 1980s, the opening of arms markets, the increasing number of potential patrons in the Middle East and elsewhere, the rise of political Islamism, and the new security agenda, post 9/11. Would be political entrepreneurs are swimming in sources of cash – aid is increasingly petty cash compared to the potential income from oil and mining, counter-terrorism and peacekeeping and crime (eg piracy and arms/human trafficking).

De Waal admits to ‘finding this political system fascinating and repugnant’ and the book makes for jaundiced, depressing reading. Everyone is on the make – politicians, lawyers, judges, civil society leaders (when they occasionally get a mention). International bodies like the African Union merely service the money circus. Politics is reduced to ‘who, whom and how much’. Aid just rearranges the incentives a bit.

A more positive finding is that by some measures, the political marketplace works rather better than what went before. Despite the threat of violence dispersed political markets and the constant negotiations and accommodations produce a kind of bounded volatility where fewer people are killed than in the previous era (the regional body count peaked in 1988). It’s analogous to the creative destruction of the market, compared to the spectacular booms and busts of Central Planning.

Any reasons to be cheerful? Not many, I’m afraid. De Waal clutches at a few fairly standard straws – urbanization, mass higher education, an emerging middle class and ICT. The message to the international community is even feebler – ‘take the money out of politics’, which is well nigh impossible according to his own analysis, and a vague appeal to human morality.

My conclusion? Read this book for its in depth knowledge and brave iconoclasm, but don’t expect to come away with some big new narrative, still less any optimism for the future of the Horn.

February 28, 2016

Links I Liked

Huge thanks for all the votes, comments (and even some alternative designs by email!) on the short list for book covers. If you haven’t voted yet, please do so – will discuss the results with the publishers later this week.

Early zeppelins were made from beaten & stretched cow intestine. 250,000 cows were needed per airship. Germany  and its allies had to abandon sausage production in the World War 1 cause. Blimey.

and its allies had to abandon sausage production in the World War 1 cause. Blimey.

The world’s top 23 languages (by number of mother tongue speakers) [h/t Richard Cunliffe]

Some great genuinely tricky issues and nuanced discussions this week:

Randomized Control Trials: gold standard or dead end? Ricardo Hausmann attacks, Chris Blattman goes for middle ground.

Do children have the right to decent work (the working children’s movement) or is child labour basically evil and should be abolished (ILO)

Development as coercion. Thoughtful piece from Chris Blattman on developmental impacts of force v freedom & research from Philippines

And another from Chris. Six brain-stretching questions on political economy – wish I was one of his students

A smart new website factchecks claims on global health and development. Beward the ‘pants  on fire’ gif!

on fire’ gif!

Good choices in the 2016 Gates letter: Bill focusses on energy, Melinda on time poverty. Reviews?

Douglas Adams nails it on relationship between your age and your attitude to new tech. [h/t Chris Dillow]

Correction of the Day [h/t Steve Silberman]

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers