Duncan Green's Blog, page 154

October 20, 2015

How to use ‘Systems Thinking’ in practice: good new guide

This was posted by

John Chettleborough

on Oxfam’s Policy and Practice blog today, and I really liked it, so here you are

you are

Ever wondered what connects Buddhism, climate change, improved governance and a flexible approach to decision making? If so….read on.

Currently if you work in the international development sector it is difficult to escape from the term “systems thinking”. It is talked about as an approach to thinking about and tackling complex development problems, an approach that offers opportunities for scale and sustainability and smart programme design. But for many the language of complexity and systems is unfamiliar, even frightening. Systems thinking is simply perceived as yet another ‘new big idea’, a fad promoted by so called ‘experts’, that will eventually be consigned to the international development recycling bin.

De-mystifying systems thinking

OK, you’re really clever. So what?

Today we’ve published an Introduction to Systems Thinking, this guide and the accompanying animation, have been produced to demystify what systems thinking is. We wish to take it out of the realm of academics, intellectuals and scientists and make it a real thing that practitioners in the field can understand and relate to. As a result you will find simple explanations in the guide, along with practical examples and links to other resources and sources of information. Rather than confound you with masses of detail, the guide is intended to set you off on a learning journey.

Take the old adage ‘give a man a fish and he will eat for a day, teach a man to fish and he will eat for a lifetime’. A systems thinking approach would force you to challenge the logic behind this seemingly obvious statement. It would encourage you to understand the role of factors that mitigate against the development of a fishery based livelihood such as climate change, pollution and over-fishing as well as the factors such as the expansion in the market for fish which might encourage such livelihoods. It would encourage you to look for underlying drivers which were leading to these conditions such as national and local governance and gender inequality.

Rocket science or real life?

The report may surprise you. It turns out that systems thinking is not actually rocket science. In fact you almost certainly apply systems thinking in your everyday life, where you have to engage with and respond to multiple economic, political and personal systems – you just don’t call it that. And despite its name, it’s not just a way of thinking, it’s also a way of seeing things and a way of acting. It’s about humility, about being prepared to be challenged and having an open mind. It’s about working with others and playing a catalytic role in the evolution of ideas rather than pushing specific pre-set paradigms. It’s about experimentation and constant, ongoing learning and adaptation.

Are we not already doing this?

There are many examples of Oxfam applying systems thinking to what it does – and you will see some of these  illustrated in the report. Systems thinking has helped governance programmes in Tanzania experiment and adapt, has brought together stakeholders in the Tajikistan water sector in an effort to find innovative solutions, and has led to a radical change in how programmes are designed in Sri Lanka. So this report is certainly not suggesting that this is a new idea. However it is also true that pressures such as linear planning, donor requirements and hierarchical relationships get in the way of systems thinking and our work and ability to have transformational impact suffers as a result.

illustrated in the report. Systems thinking has helped governance programmes in Tanzania experiment and adapt, has brought together stakeholders in the Tajikistan water sector in an effort to find innovative solutions, and has led to a radical change in how programmes are designed in Sri Lanka. So this report is certainly not suggesting that this is a new idea. However it is also true that pressures such as linear planning, donor requirements and hierarchical relationships get in the way of systems thinking and our work and ability to have transformational impact suffers as a result.

A way forward

The authors of this guide believe that a more systematic approach to the application of systems thinking across Oxfam will lead to improvements in programme design and implementation and ultimately will enable us to make a greater contribution to the goal of eradicating poverty. By putting the ideas in this report under a common banner we hope that new learning can be generated within Oxfam and an improved enabling environment for the application of systems thinking can be created. The report makes practical suggestions for what managers, advisers and programme staff can do to make this a reality.

Go on, have a look at the (5m) animation…and then dig deeper into the report. See where it takes you.

October 19, 2015

Do we need to think in new ways about gender and inequality?

Following on from last week’s post by Naila Kabeer, Jessica Woodroffe, Director of the Gender and Development  Network, argues for a change in the way we think about gender and inequality

Network, argues for a change in the way we think about gender and inequality

The recent launch of Oxfam’s Gender and Development Journal issue on Inequalities got me thinking about the much heralded ‘leave no one behind’ agenda in the new Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This concept essentially commits governments to reach those hardest to reach. If it is to be taken seriously, we will have to get much smarter about understanding the ways in which different forms of inequality interact to keep people marginalised and powerless.

It may be time for a re-think. Frances Stewart’s conceptualisation of vertical and horizontal inequality – where the experience of vertical income groups is shaped by membership of cross cutting horizontal groups based on gender, race and so on – was incredibly important and influential at a time (thirteen years ago) when there was an almost completely siloed focus on income poverty. However, now that the ‘leave no one behind’ approach is accepted under the SDGs, it may be time to develop a more nuanced framework. The horizontal and vertical framework is a beautifully simple construct that has served its purpose well; real life is messier in (at least) three ways.

But who is ‘we’?

Most importantly, we need an approach that makes space for the interaction between the different ‘horizontal groups’. As Naila Kabeer argues in her opening article, these multiple and overlapping inequalities intensify each other, rather than simply adding to the effects of the different inequalities. The notion of intersectionality, first coined in relation to race and feminism in the US, has posed a profound challenge to work on gender equality (and has challenging lessons relevant to those working on any form of inequality). So, as Mangubhai and Capraro demonstrate in the Journal, Dalit women experience the clash between socially assigned ‘degrading’ tasks for Dalits and the gendered division of labour where women do household and community cleansing, which leaves them responsible for the manual cleaning of dry toilets. And the policy ‘solutions’ fail these women too. Research in India found that education quotas for women were taken by more powerful women while the quotas for Dalits were taken by men.

Secondly, the different horizontal ‘groups’ have very varying characteristics which need to be understood and acted upon in very different ways. Gender is (at least until the LGBTI agenda is accepted) a relationship between two distinct groups – males and females – where the discriminated-against group is the majority in every country. Disability on the other hand affects a minority of the population, is a continuum where people experience different degrees of disability, and covers a wide range of characteristics. With race and ethnicity, the discriminated against group is sometimes the minority but sometimes – as under Apartheid – the majority and, increasingly, is becoming a continuum as the mixed heritage proportion of the population increases. Age is different again, with youth experiencing some forms of discrimination while the elderly face entirely different barriers; in some countries old age is privileged while in others young people have advantages.

continuum as the mixed heritage proportion of the population increases. Age is different again, with youth experiencing some forms of discrimination while the elderly face entirely different barriers; in some countries old age is privileged while in others young people have advantages.

Finally, the way the model is interpreted usually privileges income among other inequalities, inferring that it structures society in a way that other discriminations don’t. Many feminists, Kabeer included, contest this arguing that in all societies gender relations shape and structure society for both men and women just as class shapes societies for all income brackets.

Might it be time now to build on the concept of horizontal and vertical inequalities to find a more accurate – and therefore no doubt much less neat – way of understanding the full complexity and depth of interactions between different forms of inequality? It is, after all, those people facing multiple inequalities that are furthest behind.

And since several of you loved the random James Bond video on gender inequality last week, here’s another top video, from Plan International’s Mary Matheson (my sister in law, as it happens)

October 18, 2015

Links I Liked

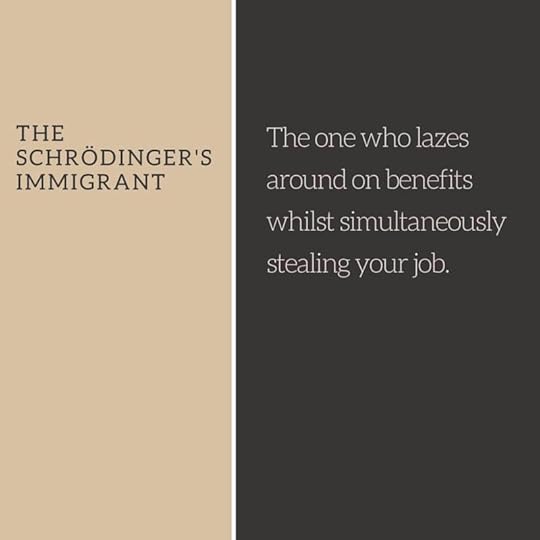

Schrödinger’s Immigrant, via Ingrid Srinath

Could the Jaded Aid satirical cardgame help reform the aid industry? Or is it just the perfect Xmas pressie for jaundiced aid workers? humanosphere.org/basics/2015/10

Poverty is falling faster among Africa’s rising number of female headed households (which are now up to 26% of the total), but we don’t really know why

Good news on Malaria deaths. Now down to 450,000 per year. Could it be wiped out altogether?

Good news on Malaria deaths. Now down to 450,000 per year. Could it be wiped out altogether?

Migrant remittances are nearly as important as Foreign Direct Investment in generating economic growth in developing countries. And both are more important than aid. Important number crunching

Call to action on neglected aspect of development: shocking photos of the treatment of mental illness in Bangladesh

Stephen Hawking says inequality is the result of political choices, not techno-inevitability

John Twigg’s Revised Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) Good Practice Review is now available for free download and comes with a cool 4m video

October 15, 2015

Why ‘Raising Your Voice’ is crucial in development, and getting harder in many countries

Today is Blog Action Day (as if you didn’t know) and this year’s theme is ‘raising your voice’. That resonates with me  for both positive and negative reasons.

for both positive and negative reasons.

On the negative side, in dozens of developing countries it’s getting a lot more dangerous to raise your voice, if what you say is not congenial to the government. States are busily swapping notes on how best to undermine and suppress civil society organizations – Ross Clare and Araddhya Mehta recently discussed the reasons for this crackdown on civil society space on this blog.

Our power as INGOs to prevent this happening is constrained, not least because we are being portrayed as part of the problem – the evil genius imperialists supposedly manipulating local CSOs. So if we just shout about oppressive governments we could end up sounding like the caricature. But we can box cleverer than that – I recently pointed out that we could do far more to help local CSOs boost their capacity to raise funds locally, and thereby reduce their dependence on foreign donors. I think we could also be much more proactive in terms of quiet diplomacy with our governments, who often share our concerns about what is happening.

Raising Her Voice group, Nepal

On the positive side, some of the work on the ground on raising voices is truly inspiring. In particular, I recommend the Raising Her Voice programme on women’s empowerment. One of the interesting aspects of that work is that it’s not enough to talk about empowerment and voice in terms of the formal, visible arena of governments, policies, decisions and spending, which so often consume the attention of advocates and campaigners. We also need to learn from the women’s movement and address the question of ‘invisible power’ and norms – the things expected and believed of different kinds of people, what is defined as right and wrong, natural and unnatural, not just at local level but across the whole society. The cultural air we breathe. This determines, for example, whether women in poor communities see themselves as having the right to speak out, and to expect others to listen.

Here’s the link to the Raising Her Voice global programme, linking women’s empowerment work in 17 countries. I also did some case studies on its work and theory of change, both globally, and in Nepal and Pakistan. RHV activists are themselves all too familiar with the closing of civil society space, as this example from Honduras shows.

And here’s a nice animation describing RHV, from the RSAnimate people

Wishing you a happy (and preferably noisy) BAD……

October 14, 2015

Why it’s time to put gender into the inequality discussion

LSE’s

Naila Kabeer

introduces a

new issue of Gender and Development

, which she co-edited

The development industry has focused mainly on the question of absolute poverty over the past decades of neo-liberal reform. Given the levels of deprivation that continue to exist in poorer regions of the world, this focus is not entirely misplaced. But it only tells us part of the story. The growing concern about economic inequality adds an important missing piece. We are better able to understand the persistence of absolute deprivation in the world when we compare the share of the world’s income and wealth that goes to its richest citizens with the share that goes to its poorest.

The story becomes more complex when we factor in questions about social inequality because this tells us that certain groups are systematically over-represented at the bottom of the income distribution and among the ranks of the absolute poor, while others are over-represented at the other end of the income distribution. The current issue of Gender and Development reminds us that gender inequality is one of the most significant of these group-based inequalities – and also one of the most distinctive.

credit: Paul Smith, Panos

Unlike other groups facing social discrimination, men and women are probably equally represented among the world’s wealthiest households, but women’s presence tends to be predicated on their relationships to wealthy men. According to Forbes magazine, there are currently 1826 billionaires in the world of which 197 are women or 11% of the total. Only 29 of these women are ‘self-made’ billionaires. The rest inherited their wealth from fathers or husbands.

Attention to the distribution of individual earnings rather than household income gives us a better picture of how gender inequality plays out at the wealthier end of the spectrum. The gender pay gap among leading Hollywood movie stars is among the more publicized recent examples of this.

But the gender gap in earnings is larger at the poorer end of the economic spectrum and its consequences far more severe. Official figures under-estimate this gap because they tend to be focused on formal work. Data on informal work in middle and lower income countries not only document far wider gender disparities but also the greater concentration of women in unpaid family labour, in other words, in work that does not provide them with any purchasing power. There are a variety of reasons for this, but one that cuts across much of the world is women’s greater responsibility for care of household members and the lesser ability of poorer households to hire others to do this work or to access technology that will reduce it.

Women’s greater disadvantage in the labour market accounts for one of the gendered dimensions of poverty that has received considerable attention in the literature. Households in which women are the primary, often sole, breadwinners for themselves and their children tend to be poorer than the rest. In the Indian context, as Mangubhai and Capraro point out, this phenomenon appears in the greater poverty of households headed by women who are widowed, divorced, separated or still unmarried after the age of 30: dispossessed of any property when their marriages broke down, stigmatized by society for their husbandless status, these women are disproportionately drawn from the most marginalized sections of society. It is clearly not husbands that these women need, but a fairer distribution of property and a fairer chance to earn their own living.

Gender disparities at the poorer end of the economic spectrum tend to be exacerbated by the intersection of gender

with other forms of group-based inequality. So, for instance, while Dalits generally earn lower incomes than the upper castes in India, Afro/indigenous groups earn less than the white/non-indigenous groups in Latin America and African-American and Hispanic women earn less than whites in the United States, women from these marginalized groups tend to end up at the bottom of the earnings distribution.

Gender mediates the experience of poverty and inequality in non-economic terms as well. Papan and Clow report that in Canada, the highest rates of food insecurity are to be found among households led by female lone parents. They also found that, in contrast to the long-standing equation between food insecurity and excessively low body mass index in poor countries, moderate food insecurity in Canada was linked to obesity or excessively high body mass index and this only affected women. It did not appear to be an absence of knowledge about healthy life styles that produced such outcomes but the harsh trade-offs of poverty which required these women to choose between ‘a rock and a hard place’: healthy nutrition came lower in their list of priorities compared to rent and medication and their own nutritional needs ranked lower than those of their children.

The link between household poverty and gender-based violence has been supported by both qualitative and quantitative studies but needs to be further unpacked. It can reflect the frustrations experienced by men from poor households unable to live up to their breadwinning responsibilities or it may reflect their reactions to women’s efforts to take on more of a breadwinning role or to take up economic opportunities provided by development organizations. But gender-based violence is not always at the hands of intimate partners. Class and caste based violence can take gendered forms. Both dalit men and women face various forms of violence at the hands of the upper castes, but dalit women bear the brunt of aggravated sexual violence which often goes unreported because of fear of perpetrators, the intervention of dominant castes or to avoid shaming the family.

Greater attention to economic inequality is long overdue but if we are to tackle the harm, suffering and injustices that lie at the core of our concern, we must not lose sight of its social causes and human consequences. That means much greater attention to gender inequality in all its manifestations within the market, within the home and in society at large.

And here’s Naila and friends, discussing the issue at a recent LSE event, in 80m of fairly ropey video (sorry about that)

or of course, you could just ask James Bond (and M, obviously)

October 13, 2015

Why those promoting growth need to take politics seriously, and vice versa

Nicholas Waddell,

a DFID Governance Adviser working on ‘Governance for Economic Development’ (G4ED)  explores the links between

governance and economic growth.

explores the links between

governance and economic growth.

Should I play it safe and join a governance team or risk being a lone voice in a sea of economists and private sector staff? This was my dilemma as a DFID Governance Adviser returning to the UK after a stint in East Africa. I gambled and joined the growth specialists in DFID’s newly created Economic Development arm. A year in, I now think differently about the relationship between growth and governance.

Eradicating poverty will not be possible without high and sustained growth that generates productive jobs and brings benefits across society. Historically, this has included boosting productivity within existing sectors as well as rebalancing economies towards more productive sectors (e.g. from agriculture to manufacturing). Such structural change or economic transformation has lifted millions from poverty.

Economic transformation can have a strong disruptive effect on political governance – giving rise, for example, to interest groups that push for accountable leaders and effective institutions. As countries get richer, more effective institutions also become more affordable. Over time, economic transformation can therefore advance core governance objectives.

Economic transformation can have a strong disruptive effect on political governance – giving rise, for example, to interest groups that push for accountable leaders and effective institutions. As countries get richer, more effective institutions also become more affordable. Over time, economic transformation can therefore advance core governance objectives.

But this is easier said than done. Economic development is an inherently political process that challenges vested interests. Often the surest ways for elites to hold onto power and profit aren’t in step with measures to spur investment, create jobs and foster growth. Shrewd power politics can be bad economics.

With this in mind, in my new role I’ve been part of a major exercise with DFID country offices to identify the best opportunities for inclusive economic growth. Unlike standard ‘growth diagnostics’, we have explicitly incorporated politics into our approach. The resulting country studies powerfully illustrate the close relationship between growth and governance challenges – in everything from extractives, to infrastructure or energy. Consider the following excerpts (with the countries anonymised):

The fundamental obstacles to promoting inclusive economic growth are primarily political in nature and not due to a lack of technical expertise or knowledge about what needs to be done.

Dependence on primary commodities provides scope for elites to enrich themselves without needing to implement reforms that improve the long-term productive capacity of the economy.

Patronage politics distorts the economy and diverts public investment away from more productive sectors. Inertia is politically safer than reform. There’s an acute lack of trust between government and the private sector.

Politically-connected economic elites have increasingly established monopolies e.g. in the fuel, transport, food

and construction sectors forcing out or intimidating smaller players.

and construction sectors forcing out or intimidating smaller players. Implications for donors

Bringing power and politics into growth diagnostics didn’t just expose the extent of the challenges. It also identified tangible opportunities and helped avoid technically attractive measures that aren’t viable. This involved going into the nitty gritty of particular sectors and constraints to find openings that build on things as they are, rather than how donors might like them to be.

Not only can the integration of politics improve donors’ growth work; a better understanding of growth and economic transformation can improve governance work. Donors sometimes imply that growth will automatically follow if poor countries develop a set package of institutions (such as secure property rights, rule of law, anti-corruption measures, free media, democratic elections etc.). These are important concerns but it isn’t so simple. There’s a risk of focusing on ideal governance destinations rather than learning from recent history of how countries have developed (and considering how future paths may differ). As Dani Rodrik argues:

Few, if any countries have grown rapidly because of across-the-board institutional reforms… Rapid growth is feasible in institutional environments that look quite distorted, and policy remedies can look quite unorthodox by the standards of the conventional rulebook… The bottom line is that successful growth promoting reforms are pragmatic and opportunistic.

Donors need to reflect this in how we work. In Nigeria, for example, I saw how DFID’s work on the oil and gas sector shunned technical reform blueprints in favour of locally-led initiatives. The programme brings together diverse players as and when they share incentives and appetite for reform – whether among government, the private sector or civil society. For example, the programme took a calculated approach to who it could work with in the Nigerian Government, avoiding the notorious state oil corporation and finding pockets of reformers elsewhere. This work has influenced major legislation; tackled illegal gas flaring; and helped recoup public funds worth many multiples of the programme’s total cost.

Time to get them better aligned?

In Nepal, DFID has focused on the huge untapped hydropower potential. Combining a flexible and politically-savvy approach with rigorous technical input has helped to attract initial deals for over $2 billion of new foreign direct investment. Arm’s length DFID support helped the Investment Board of Nepal to pave the way for investment by influencing the politics surrounding the deals – not least to address wariness about forging closer energy ties with India. More work is needed to secure the poverty reduction benefits. But getting this far is progress and could help attract further investment.

As a governance adviser, I’m familiar with thinking about the state or civil society. I’m less accustomed to probing why firms hold back from making the kind of investment that could build local productive capabilities. How often do governance staff in-country talk to local firms, entrepreneurs or investors that have walked away? This is as much about understanding the politics of informal ‘deals’ as about promoting formal rules. We also need a better understanding of how to spur economic development in severely fragile states – not least to avoid worsening conflict dynamics.

Governance work remains important in its own right. And many staple governance programmes (on public financial management, taxation etc.) contribute to economic development. But the governance agenda could focus more on economic transformation; on how it links to political change; and on the practical implications for governance work. This has little to do with ‘good governance’ prescriptions and everything to do with the context-specific political economy. Often this will be as much about using governance and political skills as spending money on governance-specific programmes. It needs to be a two-way street though. As Lant Pritchett told DFID governance advisers, ‘economists are coming your way’. Let’s make sure that we meet in the middle.

October 12, 2015

ICYMI: why civil society space is under assault around the world and other posts on NGOs

Final installment in this series of re-posts of the most read summer blogs, for those who missed FP2P due to our email notification meltdown (or your holidays).

In the 1980s and 90s civil society, and civil society organizations (CSOs) came to be seen as key players in

development; aid donors and INGOs like Oxfam increasingly sought them out as partners. So the current global crackdown on ‘civil society space’ is particularly worrying – a major pillar of development is under threat.

development; aid donors and INGOs like Oxfam increasingly sought them out as partners. So the current global crackdown on ‘civil society space’ is particularly worrying – a major pillar of development is under threat.

Ross Clarke (left) and Araddhya Mehtta (right) from from Oxfam’s Knowledge Hub on Governance and Citizenship have just put together an internal briefing on the problem, and what we should be doing about it (not published yet – there will be a public version at some point). Here they set out some of the background trends for anyone seeking to prevent or reverse the crackdown.

Trend 1: Changing nature of development financing and role of the state

As states become less dependent on western aid, they become less open to influence by western governments. [Developing Country] Governments are less tolerant of CSOs challenging ‘political capture’. In some contexts CSOs doing this are perceived as acting for the political opposition. Weak regulatory and accountability frameworks for civil society make CSOs vulnerable to this charge. Several governments exploit this vulnerability and use new regulations to restrict the space of civil society to debate or challenge their economic and political development agenda. Patterns are emerging where neighbouring states apply very similar legislation and tactics, learning from one another about how to control civil society space.

The hard-fought gains of the 1990s and 2000s on civil society space and citizen participation are being reversed. In

Graph from Civicus report (link in text)

2014, Freedom House Index recorded a decrease in freedom globally for the ninth consecutive year. When civil society criticises government policy or a private sector driven agenda, they are often labelled ‘anti-development’, ‘anti-national’, ‘politically motivated’ and even ‘against national security’. This rhetoric undermines both the legitimacy of many CSOs and their ability to operate. It further is generally coupled with a series of reforms to restrict civil society space and stifle public debate. Moreover, individuals and civil society groups are directly intimidated or violently harassed when taking on vested interests on land or natural resource investment or allocations.

Trend 2: Changing nature of insecurity

The rise of extremist groups, militarised responses to insurgency, conflicts in fragile states, and transnational crime, has led to a dominance of the security agenda. Some extremist groups have created shell CSOs to channel funding and governments use this to justify overly burdensome restrictions on all civil society groups. The security agenda’s dominance lends support to authoritarian regimes and weak democratic governments seeking to restrict civil society’s influence.

Trend 3: Changing nature of civil society organisations

As the rights-based approach gained prominence in the 1990s-2000s, civil society organisations shifted their focus from service delivery to influencing policy. Yet as space to engage in policy and political reform decreases, CSOs are pushed to focus more on non-confrontational, service delivery work. Some countries even mandate the extent to which civil society must work on the provision of services and ‘hardware’.

As the rights-based approach gained prominence in the 1990s-2000s, civil society organisations shifted their focus from service delivery to influencing policy. Yet as space to engage in policy and political reform decreases, CSOs are pushed to focus more on non-confrontational, service delivery work. Some countries even mandate the extent to which civil society must work on the provision of services and ‘hardware’.

With increased foreign funding for national CSOs comes increased scepticism of international CSOs and western donors. For example, in 2014, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace reported that 50 countries place restrictions on overseas funding for NGOs. As a result, many CSOs, particularly those with rights-based mandates, have had their funds frozen or restricted. The backlash against rights-based advocacy organisations has meant that individuals and CSOs have been put on watch lists and are forced to go underground, creating an atmosphere of fear and self-censorship. This trend also has extremely violent consequences. During the first 10 months of 2014, 130 human rights defenders were killed.

Trend 4: Changing nature of information and communication technology (ICT)

The increasing prominence of ICT is a double-edged sword. It facilitates increased voice and citizen mobilisation in powerful new ways. However, it provides equally powerful tools to monitor and restrict the legitimate activities of civil society.

Social movements increasingly use technology to connect with and learn from each other. As the Arab Spring and recent uprisings in Brazil, Turkey and Ukraine demonstrate, citizens – particularly youth – are mobilising in stronger, more powerful ways.

The spread of ICTs has also led to new legislation regulating these new spaces, often amounting to severe restrictions on freedom of expression. Governments use data that citizens willingly put online to monitor them, and employ sophisticated surveillance technologies to track and target activists. A number of countries lost ground in Freedom House’s index due to state surveillance, restrictions on internet communications, and curbs on personal autonomy. In 2013, 92 writers, 50% of PEN International’s case list, were in prison or detention for using digital technologies.

on freedom of expression. Governments use data that citizens willingly put online to monitor them, and employ sophisticated surveillance technologies to track and target activists. A number of countries lost ground in Freedom House’s index due to state surveillance, restrictions on internet communications, and curbs on personal autonomy. In 2013, 92 writers, 50% of PEN International’s case list, were in prison or detention for using digital technologies.

Trend 5: Challenges with self regulation

Many of the CSOs started in the 1990s and 2000s boom years (and some existing ones) have weak governance and accountability structures, allowing some governments to question their legitimacy. CSOs need to accept their own shortcomings in this regard. In many cases, both international and national CSOs have been either unable or unwilling to meet basic reporting and administrative requirements. Many INGOs are further perceived – rightly or wrongly – as being more concerned with their own survival than the needs of their clients. Yet although reasonable regulation is legitimate, much bureaucratic oversight has become overly burdensome – a tool to obstruct and constrain dissenting voices rather than enhance accountability. Many CSOs are unable to cope with complex, changing procedures and struggle to obtain unrestricted funding required for effective, accountable organisations.

And here’s a smart piece on the same issue from Civicus Secretary General Danny Sriskandarajah. I’ll blog again when the public version comes out

Other summer posts on NGO stuff:

How can INGOs get better? A surprisingly interesting conversation with some Finance Directors

Aid agency ex-staff are a huge wasted asset – how cd we set up an alumni scheme and what wd it do?

Learning by un-doing: the magic of immersion

Why is there no ‘Fundraisers Without Borders’? Big missing piece in development.

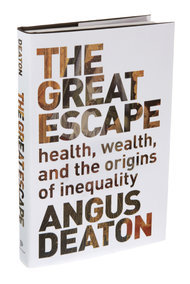

Arguing with Angus Deaton on aid

Tremendous news that Angus Deaton has won the Nobel prize in economics, particularly because this will further direct attention towards one of the great challenges of the age – rising inequality, on which Deaton is a great thinker, not least in The Great Escape, which deserves an even wider readership.

attention towards one of the great challenges of the age – rising inequality, on which Deaton is a great thinker, not least in The Great Escape, which deserves an even wider readership.

Last year, I had a public exchange with him on the From Poverty to Power blog, in which I disagreed with his criticisms of aid. Throughout, where other big economists (naming no  names….) would have ignored or slapped me down, he engaged in a thoroughly respectful and gentlemanly manner.

names….) would have ignored or slapped me down, he engaged in a thoroughly respectful and gentlemanly manner.

If you want to catch up, here are the collected blog posts:

Me: Why Angus Deaton is (mostly) wrong to attack aid for undermining politics and accountability

Angus’ reply, making the case against aid

Jon Lomoy of the OECD responds to Angus

October 11, 2015

Links I Liked

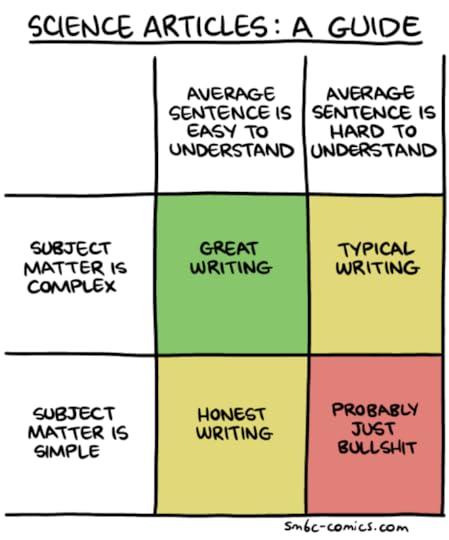

How to judge the quality of specialist writing h/t Chris Blattman

Egypt’s Chinese lingerie vendors. Brilliant, human reportage on globalization, Africa and China. [h/t Mark Fried]

China’s growing aid budget has its own Daily Mail, charity-begins-at-home style internal critics, apparently.

Trying to get your head round the World Bank’s new poverty numbers? Good explainer frm Francisco Ferreira

Got a skill and want to help Syrian/other refugees? Go to crowdsource website movements.org and sign up

Best travel ad ever? (and also another reason – besides Borgen – why I wish I was Danish) [h/t Chris Blattman]

Trevor Noah’s been getting mixed reviews as he steps into Jon Stewart’s gigantic shoes, but this riff on Donald Trump as America’s first truly African president is brilliant.

October 8, 2015

How can UK aid pursue development and British National Interest at the same time?

The British aid programme is in an interesting place right now. The British chancellor (finance minister) George Osborne is overseeing a

Should that be ‘from’ or ‘for’?

tense spending review in which aid is protected thanks to the government’s commitment to spending 0.7% of national income on aid, but most other departmental budgets are being slashed. On the Andrew Marr TV show last month Osborne said: ‘The question is not just how does our aid budget help the rest of the world, but how does it help Britain’s national interest?’ And development minister Justine Greening echoed that sentiment in her speech to this week’s Conservative party conference.

It’s hard to know what to read into this. It may just be a storm in a teacup, but everyone is on tenterhooks because money is so tight in Whitehall, prompting fears that talk of national interest could be the start of a slippery slope that ends with raids on the UK aid budget. Those fears were heightened when David Cameron, visiting Jamaica on his way back from the SDGs summit in New York, announced £25m in aid to build a prison in Jamaica so that foreign criminals in the UK can be sent home to serve sentences in the Caribbean. Officials told reporters the deal could save UK taxpayers £10m a year.

So what do we know? Some 12% of Britain’s £12bn annual aid spending currently goes through other Whitehall departments, while DFID manages the remaining 88%. That ratio isn’t expected to change much, but as one senior civil servant told me ‘we will be expected to work the Overseas Development Aid (ODA) definition hard’. The job of civil servants will be to broaden the range of spending on the British national interest that qualifies as aid in order to cross-subsidise other government priorities (security, refugees etc). And holding the line against this kind of slippage will be the independent aid watchdog, ICAI, the International Development Select Committee and assorted aid organizations, wielding some rather fuzzy OECD definitions of what can/can’t be counted as aid (eg you can count spending on the first year of resettling refugees, but not thereafter).

So how does Britain’s national interest (let’s call it BNI for short) overlap with its aid? There is clearly a powerful case for enlightened self interest, where a greater focus on longer term impact and sustainability – ending poverty, tackling inequality and building resilience worldwide – should benefit Britain by creating a more prosperous, stable world in which we can trade, travel and peacefully coexist. But that’s the extremely idealistic viewpoint, all motherhood and apple pie. Where are the real trade offs and crunch points in this debate?

So how does Britain’s national interest (let’s call it BNI for short) overlap with its aid? There is clearly a powerful case for enlightened self interest, where a greater focus on longer term impact and sustainability – ending poverty, tackling inequality and building resilience worldwide – should benefit Britain by creating a more prosperous, stable world in which we can trade, travel and peacefully coexist. But that’s the extremely idealistic viewpoint, all motherhood and apple pie. Where are the real trade offs and crunch points in this debate?

The simplest trade off is that when you insist that aid recipients use the money to buy goods and services from British companies, you may boost British industry, but the aid recipient gets less value for money. That’s tied aid, which the Conservative Party at the last election promised to avoid, and which Britain has largely abandoned (at least on goods, although the proportion of British researchers, consultancies and technical advisers benefiting from the aid programme is rather striking).

But there are other, more subtle trade-offs. Politics is often dominated by short term concerns, at the expense of long term problems, and the pursuit of BNI could easily push aid further in that direction. For example an exclusive focus on today’s crises (eg Syria) could come at the expense of building strong societies/economies that will help prevent future crises (including much of what DFID does in places that most people would struggle to place on a map, until they blow up).

What if buying a bit of short term BNI, for example by using aid to get contracts for British companies to build airports or win oil contracts comes back to bite s in 20 years time in the shape of climate change, which hits developing countries the hardest?

What we don’t want is to end up with a two tier aid programme – separate tiers for BNI and development. Perhaps

The political pressures on the aid budget are real

more likely than a completely two tier system is the creation of a chilling effect on funding activities that aren’t demonstrably in the BNI, as civil servants will prefer things they can present as win wins.

How the government interprets BNI in its aid programme has wider ramifications beyond parochial UK arguments. As I’ve argued before, at the moment the UK is an outlier (in a good way) – a cluster where aid and development are still a buzzing, dynamic sector in a world where government after government is cutting aid budgets. In that sense, the UK is acting as a keeper of the flame, so that if/when governments return to their senses (whether of self interest or good global citizenship) and recommit to aid, they can get up to speed with what works by asking DFID, among others. That makes it doubly important to keep a gold standard aid programme that is not diluted by domestic policy considerations.

This may seem like scaremongering, particularly given David Cameron’s undoubted personal commitment to aid. But someone else will be in charge of his party by the next election, and the 0.7 commitment is now enshrined in law. So if the next PM is less convinced on aid, but unwilling to scrap the law, the battleground is likely to be over how British National Interest is interpreted within the UK aid programme. Watch this space.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers