Duncan Green's Blog, page 158

August 26, 2015

Is power a zero sum game? Does women’s empowerment lead to increased domestic violence?

I’ve been having an interesting exchange with colleagues at Oxfam America on the nature of power. They argue that empowerment is zero sum, i.e. one person acquiring power means that someone else has to lose it. In a new post, OA’s Gawain Kripke sets out their case.

empowerment is zero sum, i.e. one person acquiring power means that someone else has to lose it. In a new post, OA’s Gawain Kripke sets out their case.

‘The development community should recognize that women’s economic empowerment is a threat to established power holders.

Women’s economic empowerment is a growing subsector within the development field. There’s a lot of enthusiasm and new initiatives in this area. And rightly so. There are all sorts of good reasons to focus on women, and on their economic situation, and on empowerment.

But there’s a tendency to think of women’s economic empowerment as an unmitigated good. Or perhaps to hope that it’s an unmitigated good and ignore the strong possibility that there are negative consequences as well.

That’s why I think this new paper by my colleagues is really useful and important. The paper makes an effort to parse out the impact on “domestic violence” of women’s economic empowerment. Unfortunately, there is not enough research to fully understand the linkages and correlations between the two. The anecdotal evidence is mixed. Yes, women’s economic empowerment has many benefits to women, their families, communities and even to countries. But it also seems true – at least in some cases — that it causes stress and conflict within households and communities.

When you think on it, it’s not surprising that husbands and fathers might feel threatened by empowered wives and daughters. More senior women might feel threatened by empowered younger women. That’s seems obvious, even natural. And that perceived threat might provoke negative reactions, even violence.

So why haven’t practitioners – Oxfam included – made sure that economic empowerment projects have strong strategies and safeguards to handle any blowback?

Women in a Burkina Faso Saving for Change group hold their weekly meeting. Photo: Rebecca Blackwell/Oxfam America

I think it has to do with our mindset. We tend to think of development as a technical enterprise, devoid of power and political content. The mental frame is something like a public health model – where improving things for some people (i.e. vaccines or better sanitation) doesn’t hurt other people and, in fact, has positive externalities. A lot of economics is built on frames like this, the Ricardian model, where the sum is greater than the parts and everyone can gain. Welfare of some can improve at the same time that the welfare of others improves.

But I think power is different. I think power is zero-sum. If your power increases, then, necessarily, my power decreases. There are various definitions and understandings of power. But I think the most useful understanding of power is the ability of one actor (individual, party, clique, etc.) to compel or influence others to do one’s will. In voting, expanding the franchise to new groups of voters necessarily dilutes the power of incumbent voters. Influencing other key decisions is the same. If one person decides without any consideration for others, all power is held by that person. If the decision must be shared by two people, the power of each is halved.

We can use the term “empowerment” glibly. It seems like a good thing and it fits our principles to “help people to help themselves.” We pursue women’s economic empowerment and think that everyone will be cheered by the better incomes that women make. But if we’re serious about empowerment, we need to recognize it necessarily means threatening incumbent power holders. It means women will have more money, more decision-making control, more autonomy, more agency, more influence, more power. And it is totally predictable that incumbents will resist. And even when incumbents don’t resist directly there may be social and psychological payments exacted. And as Frederick Douglass said, “This struggle may be a moral one, or it may be a physical one, and it may be both moral and physical, but it must be a struggle. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.”’

Thanks Gawain. It’s a useful reminder of the potential risks involved in empowerment programmes, but I think it’s based on a partial  understanding of the nature of power. I often use the ‘four powers’ model developed by Jo Rowlands, which sees four different kinds of power at work:

understanding of the nature of power. I often use the ‘four powers’ model developed by Jo Rowlands, which sees four different kinds of power at work:

Power within: personal self confidence and a sense of rights and entitlement

Power with: collective power, through organization, solidarity and joint action

Power to: meaning effective choice (agency), the capability to decide actions and carry them out

Power over: the power of hierarchy and domination, as described above.

Aspects of these different forms of power are indeed zero sum, but plenty are not. It seems very reductionist to argue that women getting the vote or joining a trade union somehow significantly disempowers men; and domestic violence programmes like We Can have found that men reported marked improvements in their own quality of life from respecting women’s rights in the home, not least because the sex improved, according to some (well, duh).

Thinking of things like trade unions, I wonder if your view of power is culturally determined – do Americans see it as zero sum, Europeans as more positive, with Brits somewhere in between? What do you think?

August 25, 2015

Embracing Complexity – a good new book on systems thinking (and action)

Jean Boulton is a regular both here on the blog and in the corridors of Oxfam. She’s a onetime theoretical physicist  turned consultant, and one of her passions is complexity and systems thinking, and their implications for how organizations, including development agencies, go about their work.

turned consultant, and one of her passions is complexity and systems thinking, and their implications for how organizations, including development agencies, go about their work.

Now she’s teamed up with fellow lapsed physicist Peter Allen, and (a ‘theorist and practitioner of strategy’, whatever that is) to write Embracing Complexity: Strategic Perspectives for an Age of Turbulence, a smart, 250 page introduction to complexity and its implications for action.

They are pretty evangelical about their topic:

‘Once you recognize the realities of the complex world, there is no going back, and we have titled this book Embracing Complexity for a reason. If you take on board what it means to say the world is complex, this will change the way you think, feel and act. And we think this will be a change for the better.’

True that – I see systems everywhere these days, and it has definitely changed the way I ‘think, feel and act’.

The book reflects the authors’ commitment to blending theory and practice. The first half is an introduction to the ideas that underpin complexity, contrasting it with a linear, reductionist ‘machine worldview’, pulling in discussions on everything from Plato and Aristotle to Newton, Darwin and Peter Allen’s personal hero and complexity pioneer, Ilya Prigogine.

The second half is all about applications – to management, strategy and economics, with a chapter from Jean focusing on international development, mainly devoted to applying complexity thinking to Oxfam’s programme in the Turkana region of Northern Kenya and some work on savings group in Western Kenya.

The last chapter is an edited transcript of a conversation between the three authors about what each of them sees as the importance and value of complexity thinking.

At this point, I have a confession to make: I’ve reviewed the book twice, and came to very different conclusions each time. This time I was in a bad mood, only skimmed it, and decided that it was OK but not brilliant and that ‘I was a bit frustrated with the final chapter when, rather than definitively pull together the threads of the previous chapters, they opt for a conversation between the authors. Very erudite, to be sure, and consistent with their ‘avoid blueprints and checklists’ message, but I felt it was a bit of a cop out in a book that claimed to be committed to practical implications.’

At this point, I have a confession to make: I’ve reviewed the book twice, and came to very different conclusions each time. This time I was in a bad mood, only skimmed it, and decided that it was OK but not brilliant and that ‘I was a bit frustrated with the final chapter when, rather than definitively pull together the threads of the previous chapters, they opt for a conversation between the authors. Very erudite, to be sure, and consistent with their ‘avoid blueprints and checklists’ message, but I felt it was a bit of a cop out in a book that claimed to be committed to practical implications.’

Then I found the review I wrote of the draft a year ago, which said ‘Great intro, comes across as both authoritative and conversational (hard balance to get right). It’s already got some excellent illustrative examples. Really like the conversational last chapter.’

Ouch. Enough to make you question whether reviews (or at least my versions) are worth reading at all….. OK, I realize I am now reviewing the review, let’s get back to the book.

Jean did set out a list of the principles, which was the closest I could find to an overall set of ‘so whats’:

History Matters: take time to investigate the relevant history/background of the market/country/organization

Build relationships: in this way, you learn about the past, shape approaches that are more likely to work and also are owned by people, and get more information about what is working and what is not

Weave together, with others, a vision for change: involve many perspectives and think through consequences systemically

Sometimes it may be better to start small: grow from there, or take a portfolio approach or try out several options. You can never be quite sure what will work and what will not.

Allow for customization: goals might be common but how to achieve them may depend on local circumstances,

so allow for variation in how to do things

Expect to learn and adapt as you do things: unintended consequences and unexpected changes in the wider

world are normal. Build in iterative processes for dialogue, review and adaptation

world are normal. Build in iterative processes for dialogue, review and adaptationKeep looking for change – around and ahead: take not of things that are interesting or different and triangulate these ‘qualitative perceptions’ with what others are noticing. Keep scanning widely for new factors emerging in the wider world; take a range of opinions, particularly from those close to the issues; think about the future; think a few steps ahead. You will be more attuned to change as it emerges and better able to anticipate and adapt and seize opportunities.’

These feel thoroughly sensible, mercifully jargon-free, and I wish all aid agencies adopted them.

I had a brief email exchange with Jean about this review. In her view ‘the book is best approached by reading half a chapter or a few pages at a time and then sitting with it. This is a book about mind change rather than method and as such, as Kuhn said about scientific revolutions, it takes patience to let it addle your brain and belief systems….. Its other real strength is that Peter Allen has worked full time on complexity theory for nigh on 50 years. He really really understands the maths of it, the different approaches etc. Most other authors have to take on trust others’ views of the science.’

Sounds about right. Overall I think you can add this to a list of top books on complexity, such as Donella Meadows, or the fascinating case studies in Ben Ramalingam’s book.

Wonder if other book reviewers have accidentally reviewed the same book twice, and whether (like me) they disagreed with themselves? Anyone willing to fess up?

When did you stop receiving email notifications of this blog?

I know this is a bit like saying ‘raise your hand if you can’t hear me’, but we have a problem. This blog has amassed  some 5000 email subscribers who should get an email with each new post, which is great. Unfortunately, a lot of them have been getting in touch to say they no longer get the notifications. When they go to the site to check, it tells them they are already subscribed.

some 5000 email subscribers who should get an email with each new post, which is great. Unfortunately, a lot of them have been getting in touch to say they no longer get the notifications. When they go to the site to check, it tells them they are already subscribed.

The wonderful webgeek who sorts this kind of thing out says it would help to know when people stopped receiving the emails. So fingers crossed that your inbox management is just as bad as mine- please could you tell us the date of the last alert received from ‘From Poverty to Power’?

Ta, Duncan

August 24, 2015

5 trends that explain why civil society space is under assault around the world

In the 1980s and 90s civil society, and civil society organizations (CSOs) came to be seen as key players in

development; aid donors and INGOs like Oxfam increasingly sought them out as partners. So the current global crackdown on ‘civil society space’ is particularly worrying – a major pillar of development is under threat.

development; aid donors and INGOs like Oxfam increasingly sought them out as partners. So the current global crackdown on ‘civil society space’ is particularly worrying – a major pillar of development is under threat.

Ross Clarke (left) and Araddhya Mehtta (right) from Oxfam have just put together an internal briefing on the problem, and what we should be doing about it (not published yet – there will be a public version at some point, but if you want a copy, please email Araddhya[at]oxfamindia[dot]org). Here they set out some of the background trends for anyone seeking to prevent or reverse the crackdown.

Trend 1: Changing nature of development financing and role of the state

As states become less dependent on western aid, they become less open to influence by western governments. [Developing Country] Governments are less tolerant of CSOs challenging ‘political capture’. In some contexts CSOs doing this are perceived as acting for the political opposition. Weak regulatory and accountability frameworks for civil society make CSOs vulnerable to this charge. Several governments exploit this vulnerability and use new regulations to restrict the space of civil society to debate or challenge their economic and political development agenda. Patterns are emerging where neighbouring states apply very similar legislation and tactics, learning from one another about how to control civil society space.

The hard-fought gains of the 1990s and 2000s on civil society space and citizen participation are being reversed. In

Graph from Civicus report (link in text)

2014, Freedom House Index recorded a decrease in freedom globally for the ninth consecutive year. When civil society criticises government policy or a private sector driven agenda, they are often labelled ‘anti-development’, ‘anti-national’, ‘politically motivated’ and even ‘against national security’. This rhetoric undermines both the legitimacy of many CSOs and their ability to operate. It further is generally coupled with a series of reforms to restrict civil society space and stifle public debate. Moreover, individuals and civil society groups are directly intimidated or violently harassed when taking on vested interests on land or natural resource investment or allocations.

Trend 2: Changing nature of insecurity

The rise of extremist groups, militarised responses to insurgency, conflicts in fragile states, and transnational crime, has led to a dominance of the security agenda. Some extremist groups have created shell CSOs to channel funding and governments use this to justify overly burdensome restrictions on all civil society groups. The security agenda’s dominance lends support to authoritarian regimes and weak democratic governments seeking to restrict civil society’s influence.

Trend 3: Changing nature of civil society organisations

As the rights-based approach gained prominence in the 1990s-2000s, civil society organisations shifted their focus from service delivery to influencing policy. Yet as space to engage in policy and political reform decreases, CSOs are pushed to focus more on non-confrontational, service delivery work. Some countries even mandate the extent to which civil society must work on the provision of services and ‘hardware’.

As the rights-based approach gained prominence in the 1990s-2000s, civil society organisations shifted their focus from service delivery to influencing policy. Yet as space to engage in policy and political reform decreases, CSOs are pushed to focus more on non-confrontational, service delivery work. Some countries even mandate the extent to which civil society must work on the provision of services and ‘hardware’.

With increased foreign funding for national CSOs comes increased scepticism of international CSOs and western donors. For example, in 2014, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace reported that 50 countries place restrictions on overseas funding for NGOs. As a result, many CSOs, particularly those with rights-based mandates, have had their funds frozen or restricted. The backlash against rights-based advocacy organisations has meant that individuals and CSOs have been put on watch lists and are forced to go underground, creating an atmosphere of fear and self-censorship. This trend also has extremely violent consequences. During the first 10 months of 2014, 130 human rights defenders were killed.

Trend 4: Changing nature of information and communication technology (ICT)

The increasing prominence of ICT is a double-edged sword. It facilitates increased voice and citizen mobilisation in powerful new ways. However, it provides equally powerful tools to monitor and restrict the legitimate activities of civil society.

Social movements increasingly use technology to connect with and learn from each other. As the Arab Spring and recent uprisings in Brazil, Turkey and Ukraine demonstrate, citizens – particularly youth – are mobilising in stronger, more powerful ways.

The spread of ICTs has also led to new legislation regulating these new spaces, often amounting to severe restrictions on freedom of expression. Governments use data that citizens willingly put online to monitor them, and employ sophisticated surveillance technologies to track and target activists. A number of countries lost ground in Freedom House’s index due to state surveillance, restrictions on internet communications, and curbs on personal autonomy. In 2013, 92 writers, 50% of PEN International’s case list, were in prison or detention for using digital technologies.

on freedom of expression. Governments use data that citizens willingly put online to monitor them, and employ sophisticated surveillance technologies to track and target activists. A number of countries lost ground in Freedom House’s index due to state surveillance, restrictions on internet communications, and curbs on personal autonomy. In 2013, 92 writers, 50% of PEN International’s case list, were in prison or detention for using digital technologies.

Trend 5: Challenges with self regulation

Many of the CSOs started in the 1990s and 2000s boom years (and some existing ones) have weak governance and accountability structures, allowing some governments to question their legitimacy. CSOs need to accept their own shortcomings in this regard. In many cases, both international and national CSOs have been either unable or unwilling to meet basic reporting and administrative requirements. Many INGOs are further perceived – rightly or wrongly – as being more concerned with their own survival than the needs of their clients. Yet although reasonable regulation is legitimate, much bureaucratic oversight has become overly burdensome – a tool to obstruct and constrain dissenting voices rather than enhance accountability. Many CSOs are unable to cope with complex, changing procedures and struggle to obtain unrestricted funding required for effective, accountable organisations.

And here’s a smart piece on the same issue from Civicus Secretary General Danny Sriskandarajah. I’ll blog again when the public version comes out

August 23, 2015

Links I Liked

Apologies for the interruption in normal service, but I’ve been away at the wonderful, parched-hinterland-restoring

Edinburgh fringe (8 days; 30 shows of every genre from comedy to misery, with some ventriloquism and photography thrown in – highly recommended). Apologies too for the problems with the email alerts – we’re working on fixing that. Anyway, here’s last week’s top tweets.

The biggest development story in Europe right now is on/about our borders and it is getting ever more harrowing. Photographer Daniel Etter fills in the background on his extraordinary photo of the pain on  a Syrian man’s face as he lands in Greece, which sums up the human drama more than any article, and duly went viral.

a Syrian man’s face as he lands in Greece, which sums up the human drama more than any article, and duly went viral.

Powerful and evocative piece on the daily violence in Rio by anti-gun campaigner Robert Muggah

I know I shouldn’t find this funny, but I can’t help it – especially because the girl is so obviously enjoying mowing down her little brother. Questions arise: was he OK? What was the cameraperson thinking of? Is this a gender rights activist in the making?

China has almost wiped out urban poverty. Now it must tackle inequality. Nice overview and some new stats from the ODI’s Elizabeth Stuart

Some slightly alarming generalizations in this New York Times piece (by my neighbour Katrin Bennhold) and accompanying video on the girls who ran away from school in East London to join ISIS, but good to hear the voices of the women who were their friends, relatives and neighbours coming through loud and clear.

The Authoritarian Temptation: why does the public in Russia, Hungary, Turkey etc now seem to prefer to vote for autocrats rather than the freedoms of two decades back?

Lovely piece by a Moroccan bank director (yep, really) on launching a financial product for poorer households

Great Women Inspire Girls. Another moving Plan International Girl Power video from my sister-in-law Mary Matheson (seems to be a bit of merit-based nepotism around today – hope you don’t object)

August 20, 2015

Why Al Jazeera will not say Mediterranean ‘migrants’

The whole piece is powerfully written and well worth reading (h/t Craig Valters)

“The umbrella term migrant is no longer fit for purpose when it comes to describing the horror unfolding in the Mediterranean. It has evolved from its dictionary definitions into a tool that dehumanises and distances, a blunt pejorative.

It is not hundreds of people who drown when a boat goes down in the Mediterranean, nor even hundreds of refugees. It is hundreds of migrants. It is not a person – like you, filled with thoughts and history and hopes – who is on the tracks delaying a train. It is a migrant. A nuisance.

It already feels like we are putting a value on the word. Migrant deaths are not worth as much to the media as the deaths of others – which means that their lives are not. Drowning disasters drop further and further down news bulletins. We rarely talk about the dead as individuals anymore. They are numbers.

There is no “migrant” crisis in the Mediterranean. There is a very large number of refugees fleeing unimaginable misery and danger and a smaller number of people trying to escape the sort of poverty that drives some to desperation.

There is no “migrant” crisis in the Mediterranean. There is a very large number of refugees fleeing unimaginable misery and danger and a smaller number of people trying to escape the sort of poverty that drives some to desperation.

So far this year, nearly 340,000 people in these circumstances have crossed Europe’s borders. A large number, for sure, but still only 0.045 percent of Europe’s total population of 740 million.

Contrast that with Turkey, which hosts 1.8 million refugees from Syria alone. Lebanon, in which there are more than one million Syrians. Even Iraq, struggling with a war of its own, is home to more than 200,000 people who have fled its neighbour.

There are no easy answers and taking in refugees is a difficult challenge for any country but, to find solutions, an honest conversation is necessary.

And much of that conversation is shaped by the media.

For reasons of accuracy, the director of news at Al Jazeera English, Salah Negm, has decided that we will no longer use the word migrant in this context. We will instead, where appropriate, say refugee.

At this network, we try hard through our journalism to be the voice of those people in our world who – for whatever reason – find themselves without one.

Migrant is a word that strips suffering people of voice. Substituting it for refugee is – in the smallest way – an attempt to give some back.”

Barry Malone is an online editor at Al Jazeera. Twitter : @malonebarry

August 12, 2015

Authoritarianism Goes Global: the rise of the despots and their apologists

The World Bank’s Sina Odugbemi is a stylish and impassioned writer. He also set up a deal to repost the occasional FP2P piece on the Bank’s governance blog, so I thought I’d return the compliment on his latest piece . Wish he’d write more often.

. Wish he’d write more often.

Norms, especially global norms, are exceedingly fragile things…like morning dew confronting the sun. As more players conform to a norm, it gets stronger. In the same way, as more players flout it, disregard it or loudly attack it, it begins to lose that ever so subtle effect on the mind that is the basis of its power. When a norm is flouted and consequences do not follow the norm begins to die.

Looking back now, we clearly had a magical moment in global affairs a while back. Post 1989, as the Berlin wall fell, communism ended in most places, apartheid South Africa magically turned into democratic South Africa, and so on; it seemed like an especially blessed moment. The bells of freedom tolled so vigorously mountains echoed the joyous sound. It seemed as though anything was possible, that the form of governance known as liberal constitutional democracy would sweep imperiously into every cranny of the globe.

Just as important, there were precious few defenders of autocracy in those days. Almost every regime on earth claimed to be democratic, even if the evidence was discrepant. They could at least claim to be ‘democratic’ in some utterly singular if implausible way. Now, all that has changed. Despots and sundry autocrats strut the earth. They are not ashamed. They are not afraid. They are brazen. They are in your face. They say to anyone who asks: “Hey, I am a despot. I have my own League of Despots. Deal with it”. And what is confronting the brazenness? The apparently exhausted ideals of liberal constitutionalism suddenly bereft of defenders.

The specific occasion for these reflections is the July 2015 issue of the Journal of Democracy (Volume 26, Number 3). It is a special issue focused on these matters, and I took my title from the lead essay: “Authoritarianism Goes Global: Countering Democratic Norms”, written by Alexander Cooley, Director of the Harriman Institute at Columbia University. His basic claim is as follows:

The specific occasion for these reflections is the July 2015 issue of the Journal of Democracy (Volume 26, Number 3). It is a special issue focused on these matters, and I took my title from the lead essay: “Authoritarianism Goes Global: Countering Democratic Norms”, written by Alexander Cooley, Director of the Harriman Institute at Columbia University. His basic claim is as follows:

“Over the past decade, authoritarians have experimented with and refined a number of tools, practices, and institutions that are meant to shield their regimes from external criticism and to erode the norms that inform and underlie the liberal international political order.” (Page 49)

He makes the case that the following ‘counternorms’ have been challenging “liberal democracy’s universalism – its claim to be the sole legitimate form of human governance” (page 50). I sum up his views:

Almost everywhere since 9/11 the delicate balance between individual liberty and security has tilted dangerously towards the latter.

More and more regimes are pushing the norm of civilizational diversity and non-interference in domestic affairs of sovereign states. In other words, it is nobody’s business how abysmally we treat our own citizens.

Some regimes claim to be defending the traditional values of their societies against the apparently indulgent, decadent values of liberal constitutional democracies (who, horror of horrors, now allow men to marry men and women to marry women!)

Quite apart from the counter-norms, according to Cooley the following practices and tools have been powering the ongoing authoritarian revival:

The spread of color revolutions in the 2000s has led to the emergence of an authoritarian playbook: crack down hard on independent civil society organizations and independent media.

There is also the growing practice of using as many regional organizations as possible to spread the new counter-norms, not liberal democratic values.

Giving money to awful regimes without conditionalities. Don’t worry about social and environmental safeguards or how badly they treat their citizens.

Build huge global media megaphones to spread the counter-norms.

Cooley’s essay, as well as the entire edition of the journal, are worth reading. If I have a criticism of the effort it is this: while claiming to defend liberal democracy’s universalism there is the tendency of some Western scholars to write about the defense of these values in terms of the protection of the Western world and its influence. That habit is both irritating and self-defeating. Democrats and liberal constitutionalists exist everywhere today, even in the territories controlled by sundry despotisms. These people are embracing the universalism of liberalism, its privileging of individual autonomy, human liberty, rule by consent, checks and balances in governance…the entire cathedral of foundational commitments and beliefs. Exclusionary language, and the resulting provincialism, are, in my view, deeply, deeply unwise.

Finally, there is something else at work in the world these days that the essays do not, to my knowledge, mention: the growing number of academic tomes written by Western scholars exhibiting infantile admiration for authoritarian regimes, how efficient these regimes supposedly are, how good they are at capitalism, and so on. You read reviews of these texts and you wonder if these scholars understand the true underpinnings of the social-political systems they live in and have come to so recklessly take for granted. Sometimes you think they need a spell under the jackboot of a despot before they come to their senses.

August 11, 2015

Unilever opens a can of worms on corporate human rights reporting

This guest post comes from Rachel Wilshaw, Oxfam’s Ethical Trade Manager

Hundreds of millions of people suffer from discrimination in the world of work. 1.3 billion people live in extreme poverty, surviving on less than $1.25 a day. 34 nations present an ‘extreme’ risk of human rights violations. Nearly 21 million people are victims of forced labour.

It’s an unusual opening statement for a corporate report. But then this is the first of a kind, a report from a multinational corporation applying a new method for human rights reporting.

Equally unusual is the case study (on pgs 36 and 37) on sexual harassment in Kenya. Four years ago, Dutch NGO SOMO and the Kenya Human Rights Commission alleged in Certified Unilever Tea: Small cup, Big difference? that women were not safe at Unilever’s tea estate in Kenya. Health and safety has top billing in all company codes. But they meant a different kind of safety: women’s safety from sexual harassment. Unilever, proud of its record as an employer in Kericho, pushed back: its internal processes didn’t find evidence of this, nor did the audits of independent  certifier Rainforest Alliance. In 2013 a documentary by Franco-German TV company ARTE repeated the allegations. Eventually, Unilever acknowledged that it was wrong and the NGO was right and made drastic management changes, increasing the ratio of female leaders from 3% to 40%. It also posted an account of its actions on its website.

certifier Rainforest Alliance. In 2013 a documentary by Franco-German TV company ARTE repeated the allegations. Eventually, Unilever acknowledged that it was wrong and the NGO was right and made drastic management changes, increasing the ratio of female leaders from 3% to 40%. It also posted an account of its actions on its website.

The Kericho harassment case illustrates very well why human rights’ reporting represents a significant progressive step. The tools currently relied on to assure compliance to a code or standard are simply too limited to pick up such issues as coerced sex. Why would workers tell an auditor something so sensitive, something that will stigmatise them and could put them out of a job? This means it can be highly prevalent – as is suspected across East African agriculture and beyond – but hidden by power imbalances and social norms. Human rights assurance involves “meaningful consultation with potentially affected groups and other stakeholders”, forcing open a whole can of human rights worms in supply chains. This changes the start point for meaningful action by a company, and requires a whole new mindset and toolset for corporate sustainability.

What Unilever learnt from the Kericho sexual harassment case, which came hard on the heels of Oxfam’s labour rights gap analysis in Vietnam, Labour rights in Unilever’s supply chain: from compliance towards good practice, has now permeated the Unilever Sustainable Living Plan and this report, so that women’s rights are front and centre for workers and smallholders alike. For instance, the report highlights the gap between women’s contribution to agriculture and their control over the assets they need, noting that fewer than “20 per cent of agricultural land holdings in developing countries are operated by women” (opening page and p.43), although they comprise on average 43 per cent of the agricultural labour force in developing countries. The company is now tracking the total number of women farmers in its supply chain and looking at women’s roles in household decision-making, which will help ensure that its sourcing and training strategies take gender roles into account in future. And the report’s open discussion of systemic issues such as discrimination, child labour and forced labour as well as gender-based violence, helps normalise the language and encourages other companies to discuss these reporting taboos.

The report also demonstrates tangible advances in policy and practice relating to issues Oxfam has campaigned on through our Behind the Brands campaign. For example, it states Unilever’s commitment to a zero tolerance for land grabbing, an issue which was firmly put on multinationals’ agenda in 2013 when Behind the Brands launched a targeted campaign on land rights. We look forward to the publication of the land rights policy mentioned. Unilever’s new Responsible Sourcing Policy is another example which represents a welcome shift from a compliance-based to a continuous-improvement based code.

In outlining how the company is managing supply chain risks (on pgs.52 & 53), there are several references to the need for advocacy to governments to provide an effective level playing field, and for cross-sector collaboration, both of which align with Oxfam’s asks of companies.

From better policy to measurable good practice on human rights

Of course, there are areas where we want Unilever and other companies to go further in tackling systemic issues. In  relation to workers, who get the most focus in the report, the report is still weak on living wages (preferring the less specific term ‘fair wages’) and on precarious work, a key root cause of disempowerment in workplaces. The report only scratches the surface of the challenges facing smallholder farmers, who need a predictable ‘living income’ as much as workers need secure employment on a ‘living wage’. As the Fair Trade Advocacy Office clearly articulates in its 2014 report Who’s got the power?, a better balance of power in agricultural supply chains is needed to protect small-scale producers from abuse of power and unfair trading practices.

relation to workers, who get the most focus in the report, the report is still weak on living wages (preferring the less specific term ‘fair wages’) and on precarious work, a key root cause of disempowerment in workplaces. The report only scratches the surface of the challenges facing smallholder farmers, who need a predictable ‘living income’ as much as workers need secure employment on a ‘living wage’. As the Fair Trade Advocacy Office clearly articulates in its 2014 report Who’s got the power?, a better balance of power in agricultural supply chains is needed to protect small-scale producers from abuse of power and unfair trading practices.

The gaps here suggest the company still does not have a clear narrative for positive social impact; what does ‘do good’ look like? What is a fair share of value, a living wage, a living income, what does Unilever stand for here? How far is it prepared to go ‘give up’ negotiating power in return for shared prosperity in its extended supply chain, that in the longer term ‘does good’? Can it do this in the face of shareholders’ clamour for short term returns, and when its competitors are in the grip of a business culture which is all about maximising profits and pushing ‘hidden costs’ onto society.

One thing that will help is surely to find intelligent ways to measure and report its progress on human rights and social impact, alongside commercial performance, so that shareholders can see the business is delivering long-term and civil society stakeholders can assess its progress.

We look forward to seeing this narrative evolve, but the report is a great start. We hope it catalyses a debate about how multinationals not only avoid doing harm and stay within the law, but also how to factor in the prevalence of worms in their supply chain can, and how to demonstrate that people touched by their business can escape from the poverty traps that are still far too common in factories and on farms around the world.

By carrying out and publishing this report, Unilever shows courage and leadership. But this should be just the beginning: the company needs to dive deeper into its supply chain and address the human rights of its most vulnerable stakeholders: the small-scale producers, women and men who are not directly employed by Unilever, but who supply many of its raw materials. It is by respecting their rights and by strengthening their resilience that Unilever can prove it is a truly fair and sustainable business.

August 10, 2015

Low-fee private schooling: what do we really know? Prachi Srivastava responds to The Economist

Prachi Srivastava is one of the experts on ‘low-fee private schooling’ who was interviewed for last week’s remarkably one sided Economist Paean to the Private (my words not hers). She wants to set the record straight.

I have been researching low-fee private schooling for nearly a decade and a half. In fact, the term did not exist until I coined it.

The first time I dared to speak about low-fee private schooling at an international academic conference in 2004 I was told, not-so politely and somewhat patronisingly, to hush-up. We had more pressing Education for All goals to worry about.

‘But, what about the parents making sacrifices to send their kids to these schools?’, I asked. What about states that secretly support them to show increased universal primary education numbers? (Support is less secret now in countries like India, Pakistan, and Uganda). And shouldn’t we be researching this so that we know more about issues like relative achievement, equity implications, and wider impacts on education systems?

‘There, there, dear. They’re only a fraction of total provision. It’ll work itself out.’

If at that time, I had suggested that a donor agency like DFID (and perhaps others toying with the idea) would use public monies to fund corporate-backed private school chains, I probably would have been led out in a straitjacket.

But, nearly 15 years later, here we are, and I’m more worried now than I was when I started this work. Why? Because even though we have more evidence than before (albeit concentrated in a handful of countries, i.e., mainly India and Pakistan in South Asia and Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya, and Uganda in sub-Saharan Africa), broader discussions and policy action do not reflect the literature.

Or worse yet, certain evidence gets filtered out. I recently experienced this first-hand when I was interviewed for a cover story and briefing on low-fee private schooling by The Economist (which, as the briefing notes, is 50% owned by Pearson, which in turn has stakes in Omega Schools and Bridge International Academies school chains). After nearly a two-hour interview, in which I took great pains to describe the nuances of the evidence on affordability, achievement, and the development of the sector, I was dismayed by the certainty of claims on the superiority of private provision.

Or worse yet, certain evidence gets filtered out. I recently experienced this first-hand when I was interviewed for a cover story and briefing on low-fee private schooling by The Economist (which, as the briefing notes, is 50% owned by Pearson, which in turn has stakes in Omega Schools and Bridge International Academies school chains). After nearly a two-hour interview, in which I took great pains to describe the nuances of the evidence on affordability, achievement, and the development of the sector, I was dismayed by the certainty of claims on the superiority of private provision.

Maybe this was because the lovely journalist who interviewed me and others, did not ultimately write the piece? Notes got garbled or mixed? Maybe not? Others, like Diane Ravitch, believe it’s because of the publication’s ideological stance.

Who knows? But, the fact is, in an age of quick fixes and silver bullets we are uncomfortable with long gestation periods for evidence to mature. We are uncomfortable with shades of grey. But like it or not, it’s complicated.

The low-fee sector: All things to all people?

I used the term, ‘low-fee private schooling’ for my academic study in India to operationalize what seemed to me at the time, a nebulous set of independently-owned and -operated private schools, financed wholly or nearly exclusively by user fees, and claiming to serve socially and economically disadvantaged groups. ‘Low-fee’ referred to schools that charged a maximum monthly tuition fee not exceeding the rate a daily wage labourer earned in a day. This worked out to around Rs. 70/month in rural Lucknow District and Rs. 100/month in urban Lucknow at the time.

Crucially, the term ‘low-fee’ was not used to mean fees would be considered ‘low’ by all, especially by the poorest of the poor — just that they charged tuition fees at a level lower than the more typical elite private schools we were familiar with at the time. This distinction is lost in much of the subsequent research, and many initiatives do not specify what they mean by ‘low-fee’.

This is true of the Pearson Affordable Learning Fund’s (PALF) portfolio. Nowhere does PALF state what constitutes the cut-off for an affordable learning investment. A cursory look at the published fees and costs charged by PALF’s investments in school chains showed that in March 2015 these amounted to about 62% of the income of one adult worker earning the lowest official wage in South Africa (SPARK Schools), 41% for Omega Schools in Ghana, and 8% for Bridge in Kenya.

A note of caution — any economist worth their salt will question these figures, and so they should. Fees are not

Rural low-fee private school in Lucknow District, Uttar Pradesh, India

reported consistently, and not all school costs are accounted for. We can also debate how to calculate proportional costs and household schooling expenditure — and people much better-versed than me should engage in this (if you’re interested contact me!). The point is that we need to be explicit about what we mean when we refer to ‘low-fee’, ‘low-cost’, or ‘affordable’ schooling.

So what do we know?

What does the research say? Does low-fee private schooling really offer the best chance for the ‘poor’?

Here are some (unavoidably simplified) findings based on a global review I conducted of the research. The review covered countries such as Ghana, India, Kenya, Malawi, Nigeria, Pakistan, Uganda, and others.

Affordability: Affordable for whom?

Affordability is not a one-time event. For the most disadvantaged households and daily wage earners, it is linked to insecurities related to seasonal migration for work, health (including orphaning due to AIDS), rising costs of food, among other issues. Furthermore, daily wage earnings are volatile, and most households have more than one child to school.

Evidence shows that the most insecure households, including those in Tooley and his team’s research in India and Nigeria (well-known private school advocate and co-founder of Omega Schools in Ghana, Beautiful Tree Trust schools in India, and the ancillary service provider Empathy Learning Systems in India), and most daily wage households cannot afford the ‘low’ fees charged. Furthermore, fees and costs are not the same thing. Tuition fees only constitute one part of the total out-of-pocket costs, which also include books, transportation, testing fees, uniforms, etc. Initial estimates across the literature show these can run anywhere from 3% to 30% of household income per child depending on the context.

In the face of all this, those who can, bargain or negotiate lower fees. In cases where those parents are successful, schools acquiesce because they don’t want to lose clients, since having a full school projects an image of popularity that, in turn, helps to attract more clients.

Of course, not all parents are successful. And those who aren’t, exit — usually to the state sector.

Equity: Who gets to go, and who gets left out?

Given the full costs of low-fee private schools, most disadvantaged households have to make difficult decisions about whom to send. This choice most often favours boys (also evident in Tooley and Dixon’s research in India) and aggravates gender inequities. Children from ethnic minority, lower-caste groups, and the bottom-20%-earning households have limited access (e.g., Härmä’s work in India).

Given the full costs of low-fee private schools, most disadvantaged households have to make difficult decisions about whom to send. This choice most often favours boys (also evident in Tooley and Dixon’s research in India) and aggravates gender inequities. Children from ethnic minority, lower-caste groups, and the bottom-20%-earning households have limited access (e.g., Härmä’s work in India).

Children disadvantaged by location also tend to get left out. Emerging work in India, where there is relatively more literature, shows that private schools tend to be in urban and rural areas that have relatively better public infrastructure (e.g. access to roads, electricity) (e.g., Woodhead et al’s longitudinal analysis; Pal’s work in rural areas). Private schools do not tend to reach children living in the poorest or most difficult-to-reach areas (e.g. Govinda and Bandhyopadhyay), and if they do, they are not sustainable over time. If these children have longer-term access to a school, it tends to be to a state school.

Quality: Are low-fee private schools really better?

The full portfolio of evidence is inconclusive.

On achievement: No study shows a universal private school advantage for every group of private school student, in every subject, across all contexts. Furthermore, private school advantage, where it exists, tends to diminish or disappear when background characteristics are controlled for. This is also evident in Tooley and his team’s research in India and Kenya, and in a randomized control trial, often dubbed the ‘gold standard of research’, in Andhra Pradesh, India by Muralidharan and Sundararaman. In some instances, as the 2009 ASER results showed, there was a negative effect of private school attendance on learning levels in local language. Crucially, as the DFID rigorous review found, studies show low attainment overall in government and private sectors. Impacts on higher order skills, like creativity and critical thinking, are not known.

On inputs: Evidence is mixed regarding school infrastructure. Low-fee private schools are better than state schools on some inputs, and worse on others. But overwhelmingly, studies show that the main way low-fee private schools keep costs ‘low’ is to hire unqualified, short-term contract teachers and pay them extremely low wages, sometimes below the minimum wage. The key is primarily to recruit teachers who are young, local women since they are ‘the cheapest source of labor’, as Andrabi et al. state regarding their work in Pakistan. This raises serious broader issues about the para-skilling of teachers and the potential exploitation of the female labour market, particularly in contexts where teaching is one of the only viable jobs for young women.

on some inputs, and worse on others. But overwhelmingly, studies show that the main way low-fee private schools keep costs ‘low’ is to hire unqualified, short-term contract teachers and pay them extremely low wages, sometimes below the minimum wage. The key is primarily to recruit teachers who are young, local women since they are ‘the cheapest source of labor’, as Andrabi et al. state regarding their work in Pakistan. This raises serious broader issues about the para-skilling of teachers and the potential exploitation of the female labour market, particularly in contexts where teaching is one of the only viable jobs for young women.

On official recognition as a quality marker: In most countries, private schools are meant to go through a process of recognition once they meet basic standards or quality norms. This is supposed to be a mark of baseline quality. However, studies in India (Ohara; Srivastava; Tooley and Dixon), Kenya (Stern and Heyneman), Nigeria (Härmä and Adefisayso; Rose and Adelabu), and Pakistan (Humayun et al.) find low-fee private schools may gain recognition through corruption and bribery. Delayed inspections, lost forms, postponed committee meetings, cumbersome paperwork, and complex land registration requirements, prompt many owners to pre-emptively open their schools without recognition, operate underground, or bribe officials without meeting set norms. This further undermines the education sector as a whole.

The growth of the low-fee private sector has been widely attributed to dysfunctional state schools. But state failure should not be tacitly accepted, certainly in light of the evidence. The fact remains that the majority of the poorest, most disadvantaged children in poor countries continue to access dysfunctional state schools. And all of us, including the private sector, have a role to play in making sure they get better.

Prachi Srivastava (@PrachiSrivas ) is an Associate Professor in the School of International Development and Global Studies, University of Ottawa. For more visit www.prachisrivastava.com.

August 9, 2015

Links I Liked

Well, the blog makeover has been met with a fine blend of approval and indifference – heart-warming stuff.

Well, the blog makeover has been met with a fine blend of approval and indifference – heart-warming stuff.

The world is getting a lot better in lots of ways, and Max Roser has a graph for all of them

The US is getting a bit of a pasting from assorted economists: Jo Stiglitz thinks it’s on the wrong side of history on tax and other global reforms. Jose Antonio Ocampo agrees – last month’s Financing for Development summit in Addis was a defeat after 13 years of progress on international tax cooperation, says Jose Antonio Ocampo

Positive framing meets climate change denial, thanks to the New Yorker

Positive framing meets climate change denial, thanks to the New Yorker

Does the developing world need a welfare state to eliminate poverty? Some insights from history. [h/t Shanta Devarajan]

Great myth-busting on migration, swarms, Calais etc from Channel 4 News

And it’s off to Africa

Meet the Humans of Kibera, Africa’s largest slum. Pics and interviews  modeled on Humans of New York

modeled on Humans of New York

From strongmen to strong institutions: Africa’s slow transition towards more political contestability by Vera Songwe

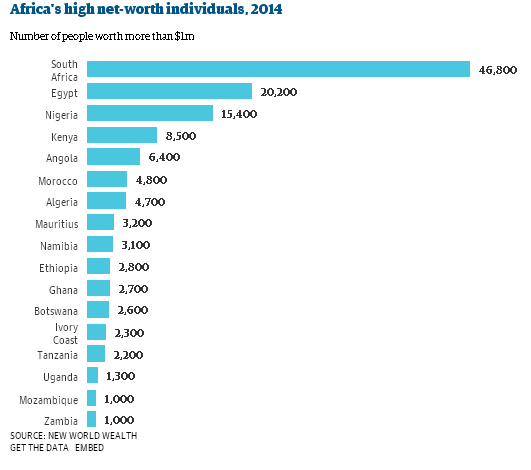

Africa wealth report 2015: Inequality growing within countries

Africa wealth report 2015: Inequality growing within countries

Driver v cyclist: this epic confrontation has got 4.5m hits in a week. I’m a London cyclist, but it’s hard to like either of them. But hey, it’s great theatre with a painful-looking denouement. Health warning, the language is pretty ripe. [h/t Finlay Green]

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers