Duncan Green's Blog, page 157

September 9, 2015

What are the drivers of change behind women’s empowerment at national level? The case of Colombia

Just read a new case study of women’s empowerment in Colombia, part of ODI’s Development Progress series  (summary here, full paper here). What’s useful is the level of analysis – a focus on the national rather than global or a project case study enables them to consider the various drivers of change at work. Some excerpts:

(summary here, full paper here). What’s useful is the level of analysis – a focus on the national rather than global or a project case study enables them to consider the various drivers of change at work. Some excerpts:

Signs of Progress:

Colombia is home to the longest armed conflict in Latin America. In this context, women have mobilised effectively to influence emerging law on transitional justice mechanisms and to ensure that understanding the gendered experiences of conflict informs policy and law.

Colombia has more women in relevant decision-making positions than ever before. In 2011, 32% of the cabinet were women, compared with 12% in 1998; in 2014, 19.9% of parliamentarians in the Lower House and 22% in the Senate were women, compared with 11.7% and 6.9% respectively in 1997.

Girls’ enrolment in secondary and tertiary education outperforms boys’, while women’s participation in the labour market has also seen sustained progress. Women constituted 29.9% of the labour force in 1990; by 2012 this had risen to 42.7%.

Constitutional reform and political opportunity structures

The 1991 Constitution is especially significant. Key elements of the new constitution included a more competitive and open political system and a new Constitutional Court with extensive judicial review powers, which over the years has acquired legitimacy. It also created an expanded Bill of Rights – grounded on principles of equality and non-discrimination, and with explicit reference to social and economic rights – which has been an important legal platform for gender equality.

Collective action: women’s social movements

Whereas women’s movements were not visible in the political process of negotiation leading up to the 1991 Constitution, there has since been a marked change in their ability to navigate the political and institutional environment to good effect, resulting in concrete advances in law and policy across a range of gender issues.

International factors

International support for women’s organisations has been fundamental in ensuring their survival and capacity to  mobilise; support to various entities that have given voice to the needs and rights of victims – including women – such as the Centre of Historical Memory, the Victims Unit, the Public Prosecution Office and the judicial branch. Donor agencies have played an important role in ‘accompanying’, facilitating or brokering relations between different actors where the risks associated with women’s activism are high and considerable distrust exists between different stakeholders. This has especially contributed to giving protection to women’s organisations in the context of conflict, and especially at the sub-national level. The third relevant factor is the role of international human rights bodies and Colombia’s commitments to international human rights conventions.

mobilise; support to various entities that have given voice to the needs and rights of victims – including women – such as the Centre of Historical Memory, the Victims Unit, the Public Prosecution Office and the judicial branch. Donor agencies have played an important role in ‘accompanying’, facilitating or brokering relations between different actors where the risks associated with women’s activism are high and considerable distrust exists between different stakeholders. This has especially contributed to giving protection to women’s organisations in the context of conflict, and especially at the sub-national level. The third relevant factor is the role of international human rights bodies and Colombia’s commitments to international human rights conventions.

Gains in gender equality: longstanding social and economic indicators of progress

Overall, there have been sustained improvements in gender equality related to education, economic and health indicators.

It’s not all hunky dory, of course, and the report highlights some important challenges to women’s empowerment: the peace process is fragile, many of the root causes of conflict such as land, inequality and exclusion are unresolved; political, generational and class divisions weaken the women’s movement and entrenched gender bias persists in politics and elsewhere, the rule of law remains weak, especially in rural areas.

The report concludes:

Progress has also been uneven. For the most part, it is well-educated and urban women who have been able to benefit most from the gains made, while women in rural areas, who are often poor and illiterate, continue to lag behind and are also much more exposed to the risks of gender-based violence, discrimination and displacement.

What I like about the report is the way it acknowledges the multiple drivers of change and how they interact – national politics, global processes and the multilateral system, grassroots organization, long term economic structures, and that it’s grown up enough to say ‘thinks have got better, but there’s still a lot of bad stuff going on’ in a field that too often demands that you decide whether your cup is half full or half empty. My only criticism is that, in the summary at least (what you expect me to read the whole thing?!) there is little attention to the dynamics of change – the critical junctures, other than the new constitution, and I didn’t see much reference to the role (positive or negative) of unusual suspects, (eg faith groups, private sector, academics, media) whether as allies of the women’s movement or separately.

I haven’t had time to review all the Development Progress studies, so if there are any particularly good ones, please let me know.

September 8, 2015

How are countries treating their over-60s? New Global Agewatch Index

[nb the elves tell me they think they may have fixed the email notification problem – if you’ve received an email for the first time in months, linking to this post, cd you say so in comments or in the poll, right?]

The 3rd annual Global AgeWatch Index (28 pages) is published today, ranking 96 countries on how they treat their older people.

The index covers 91 per cent of the world’s population aged 60 and over (lack of data prevents them including the rest, including the vast majority of African countries).

Some highlights:

‘Growing older is an experience we all share. Today’s over 60s are the world’s fastest growing population group, profoundly affecting our economies, living arrangements, and personal and professional aspirations.

Although it is not always recognised as such, global population ageing is the great success story of human development, resulting as it does from falling birth rates and longer lives. However, not all governments have yet put the policy frameworks in place to respond to the challenges posed by the ageing of their populations.

How the Index is constructed

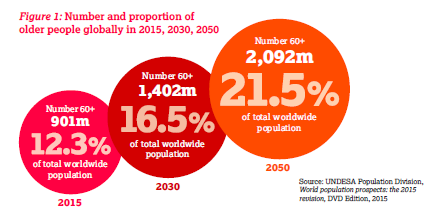

There are currently around 901 million people aged 60 or over worldwide, representing 12.3 per cent of the global population. By 2030, this will have increased to 1.4 billion or 16.5 per cent, by 2050, it will have increased to 2.1 billion or 21.5 per cent of the global population.

People over 60 now outnumber children under five; by 2050, they will outnumber those under 15. These demographic changes are most rapid in the developing world which, by 2050, will be home to eight out of 10 of the world’s over 60s.

Old age is still often considered from the economic perspective, with assumptions of what the ageing population will cost. Yet wellbeing in later life is an accumulation of experiences throughout life. Countries that support human development throughout life are more likely to have higher rates of participation of older people in volunteering, working and engaging in their communities.5 Every person should be able to live the best life that they can at every stage, with dignity and freedom of choice. As countries age, they need to invest in supporting the contributions, experience and expertise of their growing number of older citizens.

An example is Japan (8), a hyper-ageing country, with a third of the population over 60. In the 1960s, it adopted a

Rise of the Elders

comprehensive welfare policy, introduced universal healthcare, a universal social pension, and a plan for income redistribution, low unemployment rates and progressive taxation. This investment has paid off with a healthier labour force and increased longevity. As a result, Japan is not just the oldest, but also one of the healthiest and wealthiest countries in the world.

Inequality in health, education and income levels of older people is increasing between top-ranked, high-income countries and bottom-ranked, predominantly low-income countries.

This rise in inequality is reflected in the comparison of the average life expectancy in the 10 countries ranked at the top with the 10 countries ranked at the bottom. It shows that on average in 1990, people in the bottom 10 countries lived 5.7 years less than people in the top 10 countries. By 2012 this gap had increased to 7.3 years.

A lifetime of gender discrimination combined with the inequality of old age can have a devastating effect on older women. Many women are denied access to the formal labour market and instead work as carers of children and other family members. Globally, 46.8 per cent of women aged 55 to 64 are economically active, compared with 73.5 per cent of men.12 Women working outside the home usually earn less than men, so opportunities to save for later life are limited, significantly increasing the risk of poverty.

In Western Europe, 86.5 per cent of women of retirement age receive a pension, compared with 99.2 per cent of men. In Central and Eastern Europe, the figures are 93.8 per cent and 97.2 per cent respectively, while in Latin America, 52.4 per cent of women and 62.3 per cent of men receive a pension.’

And here’s the league table for you to mull over – the report doesn’t go into who’s doing better/ worse than in its first report (2013), presumably because the data isn’t strong enough yet, but once it has published a few more years, that will be an interesting area to explore.

September 7, 2015

What difference do remittances and migration make back home?

Reading the Economist cover to cover is an illicit pleasure – it may be irritatingly smug and right wing, especially on anything about economic policy, but its coverage on international issues consistently goes way beyond standard news outlets. This week’s edition had everything from the changing face of Indian marriage to the spread of pedestrian and cycling schemes around the world to (for science geeks) the intriguing question of why time is irreversible.

Reading the Economist cover to cover is an illicit pleasure – it may be irritatingly smug and right wing, especially on anything about economic policy, but its coverage on international issues consistently goes way beyond standard news outlets. This week’s edition had everything from the changing face of Indian marriage to the spread of pedestrian and cycling schemes around the world to (for science geeks) the intriguing question of why time is irreversible.

But the standout piece was on the impact of migration and remittances on Kerala, in South India:

‘Last year India received $70 billion in remittances—more than any other country in the world. The state of Kerala got far more than its fair share. A comprehensive household survey organised by Irudaya Rajan of the Centre for Development Studies, a local academic institution, finds that 2.4m Keralites were living and working overseas in 2014. The money they send home is equivalent to fully 36% of the state’s domestic product. “For all practical purposes, it’s a remittance economy,” says C.P. John of the state government.

Economic migration has become so widespread that global remittances are now worth more than twice as much as foreign aid (see chart). Many countries depend on them: remittances are worth 10% of the Philippines’ GDP and 42% of Tajikistan’s. But Kerala has been hooked on remittances longer than most. It shows how they can reshape an economy.

Somewhere to come home to

The most obvious effect, evidenced by the fancy houses, is to make a place richer. Kerala was already one of the better-off states in India when mass migration to the Gulf began, in the 1970s. It is now about 50% wealthier per head than the national average. Migrants are disproportionately Muslim and well-educated; their families have done best. The poorest have mostly stayed put. Partly as a result, Kerala is now one of the most unequal states in India—rather embarrassingly, given its socialist political traditions.

Mr Rajan’s survey shows that households are much more likely to own refrigerators and the like if a family member works abroad. Above all, though, remittances are spent on new homes. Saji Thomas of Heera, a construction firm, says that about 70% of his customers are emigrants or returned emigrants. Some move their ageing parents out of the countryside and into new high-rise flats close to good hospitals. Partly as a result, Kerala has become India’s fastest-urbanising large state. In 2001, 74% of Keralites lived in rural areas. By 2011 the proportion had fallen to 52%.

Something similar is happening in Nepal, where remittances have risen quickly and now amount to 29% of the economy. The Kathmandu metropolitan area is growing by about 4% a year—faster than almost any other large city in South Asia. Even though agricultural wages are rising, rural Nepal is losing workers.

When money flows from abroad, people not surprisingly stop working back-breaking jobs. This shift is especially beneficial for children. During the Asian financial crisis in 1997-98, the Philippine peso collapsed, increasing the value of remittances to that country. Dean Yang of the University of Michigan has shown that families responded by pulling their children out of jobs and sending them back to school. Girls benefited more than boys. Western Union, a giant money-transfer firm, reckons 30% of the money that flows through its system is spent on education.

As the supply of willing workers diminishes, wages rise. Mr Thomas reckons that construction costs in Kerala are 20-

Migrant labourers in Dubai

25% higher than elsewhere, mostly because labour is so expensive. This imbalance has encouraged a large internal migration. Many of Mr Thomas’s builders are from Bengal and Orissa, in north-east India, though Keralites still do skilled jobs such as installing air conditioning.

It is oddly hard to work out how emigration affects a country’s long-term economic prospects. Data are patchy: an apparent global surge in remittances since the 1990s is mostly the result of better reporting. And it is hard to separate cause from effect. When a country’s economy slumps, emigrants might well send more money home, making it seem as though the payments have caused the problem.

In Kerala, some suspect that remittances have fostered complacency; at the least, they have opened an embarrassing gap between the state’s wealth and the vigour of its businesses. Mr John looks enviously at nearby Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, with their factories and IT office parks, and asks why Kerala has been unable to provide more jobs for ambitious young people.

With its lovely climate and educated populace, Kerala might have created a leading university, but has not. Some believe there might be a future in medical tourism: perhaps Gulf Arabs have become so accustomed to Keralites that they will travel to the state for treatment.

Still, the biggest danger posed by remittances is that they may dry up. Gulf countries are always talking about pushing migrants out of skilled jobs to make way for natives. And Keralan migrants face rising competition from compatriots from the north and Nepalis, among others. The states of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh now export more people, at least as measured by India’s border authorities, though Kerala still sends a greater share of its population.

That might not be the end of it, though. Keralans are a coastal, outward-looking people, seemingly addicted to migration. They were pioneers in the Gulf and ought to be able to find new destinations with even better prospects. Mr John has a child in Britain; the promised land is America.’

Are From Poverty to Power posts now reaching your email inbox? If so please tell me.

OK, the IT elves think they have sorted out the glitch that has meant lots of people have not been getting email  notifications of new posts. But they want to test it. So please could you let me know on the poll over there to the right (or above) whether you have

notifications of new posts. But they want to test it. So please could you let me know on the poll over there to the right (or above) whether you have

a) been getting email notifications all along

b) have not received them (probably since late June) but have got this one

c) are still not receiving them (and yes, I realize this is a tricky category!)

When I find out a) if it’s fixed and b) roughly how many people have not been receiving the emails, I can decide how many catch-up posts of most read blogs since June to inflict on you

Thanks

Duncan

Update: OK, the IT elves may have been a little over-optimistic, they’re having another go

Note: There is a poll embedded within this post, please visit the site to participate in this post's poll.

September 6, 2015

Links I Liked

For the data geeks:

Makes sense to me

Spurious Correlations. Absolutely wonderful geek humour. [h/t Alan Beattie]

A data revolution is underway. Will NGOs miss the boat?

Myth-busting on China and development:

Data on Chinese investment in Africa show its nothing like the giant, resource-sucking caricature

The new China-dominated Asian International Investment Bank (AIIB) is to offer loans with fewer strings attached than conventional aid donors like the World Bank – competition is a good thing, right?

Beware of physicist fathers (see left, that’s me). [h/t Credit: Zachary Kanin]

Beware of physicist fathers (see left, that’s me). [h/t Credit: Zachary Kanin]

Analysis of 18 big global health organizations’ use of social media. UNICEF is the top dog. Anyone done it for development organizations?

Afghanistan tackles hidden epidemic of mental ill-health and PTSD. Massively underestimated development issue

12% of sub-Saharan Africans have mobile money accounts, compared to the global average of just 2%, according to a new digital inclusion index

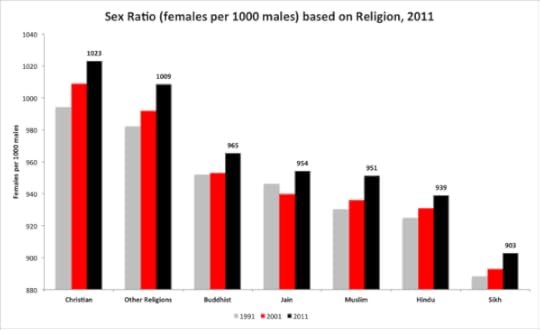

Indian sex ratios for different religions 1991-2011: anti-women bias improving but still a long way to go, especially for Sikhs. (Globally, 107 boys born for every 100 girls, but women live longer, so average is about equal numbers)

September 3, 2015

Is it useful/right to see Development as a Collective Action Problem?

Could everyone just sit down please?

The Developmental Leadership Programme is producing a good series of bluffer’s guides Concept Briefs. The latest is on Collective Action (previous ones on Political Settlements and State Legitimacy). They’re just 3 pages, including further reading, and are ideal for anyone who wants to impress in a meeting by bandying around the latest jargon.

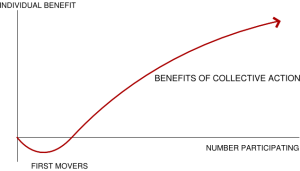

According to the paper, written by Caryn Peiffer, ‘ A collective action problem arises when the members of a group fail to act together to secure an outcome that has most potential to benefit the group as a whole.’

I like to think of it as the problem of standing up at football matches – if everyone sits down, they could all see just as well, but how do you get everyone to sit down?

In development, collective action problems cover everything from climate change (the greatest collective action problem in history), to curbing corruption or ending the race to the bottom on tax competition (‘if I/we don’t do it, others will – I’ll just lose out and look like a mug’) or more subtly, the effort of setting up new institutions that benefit everyone, including future generations, but take a lot of time and energy to establish.

In development, collective action problems cover everything from climate change (the greatest collective action problem in history), to curbing corruption or ending the race to the bottom on tax competition (‘if I/we don’t do it, others will – I’ll just lose out and look like a mug’) or more subtly, the effort of setting up new institutions that benefit everyone, including future generations, but take a lot of time and energy to establish.

The paper sets out two reasons why groups struggle to address collective action problems:

Type A: ‘Coordination: Collective action problems tend to persist because the efficient coordination of many group members is difficult. For example, a vibrant, highly participatory democracy is viewed as a collective benefit, especially from a Northern perspective. However, civil society groups can face significant coordination challenges when trying to mobilise citizens to vote.’

Type B: ‘Diverging interests: Some citizens may decide it is in their interest to act in concert for the collective good, while others may not. If only a few of the potential actors mobilise, the collective good may not materialise to its full potential.’

This is a really useful distinction, and goes to the heart of why I feel unconvinced/worried by a lot of the talk about development as being primarily about confronting collective action problems. Type A is the football match problem – how do you get everyone to sit down at the same time? You either need an authority figure with a megaphone, or a high level of mutual trust and a way of getting everyone to commit – for example taking the pledge (the paper cites Transparency International’s Integrity Pacts on anti-corruption as an example).

But type B is about power, politics and conflicting interests. Some people have vested interests in climate change, or  conflict – they are not going to magically change their ways just because the issue is misleadingly presented as a type A problem. That may even apply to the Integrity Pacts, for all I know – corruption is clearly a lot more than a simple coordination problem; a lot of people get rich from it, and are not going to give up their cashcow because of signing some pact.

conflict – they are not going to magically change their ways just because the issue is misleadingly presented as a type A problem. That may even apply to the Integrity Pacts, for all I know – corruption is clearly a lot more than a simple coordination problem; a lot of people get rich from it, and are not going to give up their cashcow because of signing some pact.

The reason I’m worried is that it seems to me that there is a tendency to interpret type B problems as type A – reflecting the aid and development industry’s deep preference for technocratic solutions that airbrush out power, politics and struggle. As the paper acknowledges:

‘Development might not be best understood as a collective good. Hughes and Hutchinson (2012) argue that it is problematic to view development challenges as collective action problems, because this mistakenly casts development as a collective good. They suggest that even the most encouraging developmental trends are the consequence of political struggles among groups, where net ‘positive’ results often come at the cost of certain parties suffering, having to compromise their position and/or losing access to certain resources.’

Exactly. All reminiscent of the recent debate on this blog over whether empowerment is a positive or zero sum game and what kind of mixture of the two pertains in different situations.

One other caveat: even if you accept that some problems require politics and struggle rather than just nice technocratic type A approaches, there are still likely to be type A problems nested within them. Take the problem of activism for example – how do you convince enough people to give up their day to go on a demo or do community work, when they could be sitting at home watching the telly? Or on a different scale, to take the kinds of risks involved in protesting in Tahrir Square or anywhere else where the possible outcomes include a beating, tear gas or worse? I know he’s seen as damaged goods these days, but Malcolm Gladwell is very good on that.

One other caveat: even if you accept that some problems require politics and struggle rather than just nice technocratic type A approaches, there are still likely to be type A problems nested within them. Take the problem of activism for example – how do you convince enough people to give up their day to go on a demo or do community work, when they could be sitting at home watching the telly? Or on a different scale, to take the kinds of risks involved in protesting in Tahrir Square or anywhere else where the possible outcomes include a beating, tear gas or worse? I know he’s seen as damaged goods these days, but Malcolm Gladwell is very good on that.

September 2, 2015

Aid agency ex-staff are a huge wasted asset – how cd we set up an alumni scheme and what wd it do?

Life after Oxfam?

I regularly hear from friends who have been cold called by their old university, seeking to extract money from them for the alma mater (apparently hungry current students are particularly convincing). That got me thinking – how come aid organizations don’t do more with their alumni?

Because Exfam staff (as we call them) are a wasted asset: many go on to influential jobs elsewhere in the development sector, or in formal politics both in developing countries and in the UK, where I know of at least two Exfam MPs, a few lords and a couple of ambassadors.

Here are five potential roles for an alumni network:

Eyes and ears

Fund-raising

Advocacy

Research support

Programme support

Eyes and Ears:

Fit for the Future argues that aid agencies need to be better embedded in political, social and economic contexts to pick up and respond to trends. Alumni schemes could provide just such a network, eg alerting NGOs to threats to civil society space, perhaps answering a monthly question(s) that they want to consult on. Fund-raising:

Fund-raising:

Have to be careful how we do this, as previous research shows alumni are often reluctant to cough up large amounts of quids for general fund raising (do they know too much?) What kinds of funding might appeal – sponsor an activist? An Enterprise Development Programme style combo of mentoring and cash?

Advocacy:

This strikes me as the highest potential area. For example:

Issue a call for Exfamers working on particular sectors (extractives, finance, UN system) to set up support groups along the lines of Amnesty Business Leaders Group (see blog post here)

Exfamers now in governments or multilaterals could advise on advocacy strategies

Research Support:

A lot of Exfamers end up in academia. We could use them and their students to deepen our research capacity, or influence future generations of decision makers (blog here)

Programme Support:

How best to harness all that expertise and experience? Pro bono evaluators? Technical assistance along the lines of Pierre Landell Mills ‘Partnership Transparency Fund’, which gets retired civil servants out to support governance and anti-corruption work around the world? Fund revisits to old projects to assess long term impact?

How to Nurture the Network: Worth looking at University alumni schemes for ideas – they invest significantly in them, even though their purposes are more limited (just fund raising, really) than ours could be. What would attract people to stay and participate?

Over to all Exfam/ex-anything readers – what would attract you to sign up to an alumni network, and what roles would make sense?

September 1, 2015

I need your help: what to read on the international system; TNCs; leadership?

OK, I need some help from the FP2P hive mind. I am getting to the crunch point on the much-trailed How  Change Happens book. I have an October deadline for a consultation draft – you’ll be hearing from me at that point. To get there, I need to do some more background research in a few areas. Could you help me with suggested reading? Three big chunks:

Change Happens book. I have an October deadline for a consultation draft – you’ll be hearing from me at that point. To get there, I need to do some more background research in a few areas. Could you help me with suggested reading? Three big chunks:

The International System:

How has the international system (UN, WTO, Bretton Woods, regional bodies, ILO etc) arisen and evolved?

How is it changing today (rise of regional bodies, new BRICs-based organizations etc)?

How does it in practice drive social/political change in developing countries? Is it through hard power (international law, treaties etc) or soft (impact on norms, sharing of knowledge and ideas)

Any particularly good profiles of the history of particular international bodies and their impact in driving change?

TNCs:

How have transnational corporations arisen and evolved?

How are they changing today (rise of southern TNCs)? What are the drivers of such change?

How do they in practice drive social/political change in developing countries (whether intentionally or by accident, positive or negative)? Is their impact mainly direct (through jobs, tax revenues, consumers) or indirect (tech spillovers, impact on practices of domestic firms). Is Corporate Social Responsibility a significant part of their overall impact, or a marginal activity?

Any particularly good profiles of the history, evolution and impact of particular TNCs?

What distinguishes good from bad leaders in terms of their personal formation, the systems in which they operate, and how they think and behave? Good leaders are here understood as nation builders who avoid grabbing the spoils, move political systems to a programmatic rather than patronage base, have an orderly succession when they step down, and bring improved stability, prosperity and respect for rights. Any really good biographies?

Similarly, what factors create good leaders at grassroots and activist level?

I’m looking for foundational books – big overviews like the Fukuyama history of the state I reviewed recently – and in-depth case studies. I’m interested in how these organizations and people drive change (I’m already pretty well covered on how NGOs and other activists in turn can change them). I’m not that interested in academic papers recycling vague jargon and generalizations or (shudder) the ephemera of blogs (not that any of you would have any truck with such things, I’m sure).

Over to you.

August 31, 2015

Links I Liked

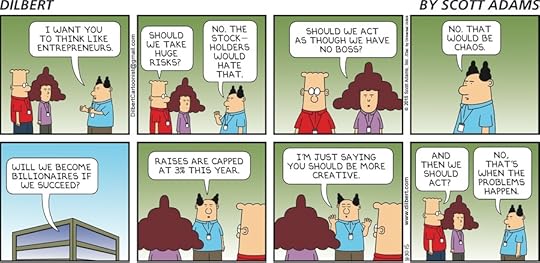

Dilbert explains: Why asking staff in big, cumbersome organizations to be more entrepreneurial is never going to

work. Sorry.

Useful tips here. Why presenting research & policy recommendations to governments is like discussing ugly babies with their parents

Irony watch: Guy in ‘lower taxes, less government, more freedom’ T shirt thanks US government firefighters for saving his house

Irony watch: Guy in ‘lower taxes, less government, more freedom’ T shirt thanks US government firefighters for saving his house

Alex Evans was on form last week: Sweetly written piece on the transformational power and low cost of savings groups in Ethiopia and a top rant about wimpy climate change negotiators, previewing his forthcoming paper on how carbon trading can keep warming below 2 degrees

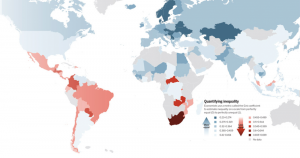

Income inequality by country, from 2014 issue of Science: Latin America  the most unequal continent, but South Africa the worst country, [h/t Max Roser]

the most unequal continent, but South Africa the worst country, [h/t Max Roser]

TS Eliot manages to nail both most academics and most pundits in one para, almost 100 years ago (1921)

TS Eliot manages to nail both most academics and most pundits in one para, almost 100 years ago (1921)

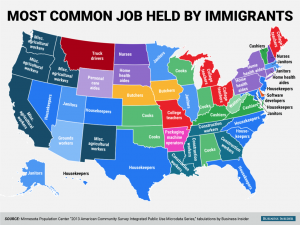

Most common job held by migrants for each US state. Gives a great sense of diversity and richness of immigrant contribution. [h/t Conrad Hackett]

Hooray! The incomparable Hans Rosling is now commentating on/explaining current events. Here he is with 2m on the EU’s (mis)treatment of Syrian Refugges [h/t Alice Evans]

August 27, 2015

Development 2.0, the Gift of Doubt and the Mapping of Difference: Welcome to the Future

Just came across this great post by the ODI’s Arnaldo Pellini, summarizing a recent talk by Michael Woolcock, the World Bank’s Lead Social Development Specialist. Michael is one of the big brains pushing the ‘Doing Development Differently’ agenda. What struck me in particular is the emphasis on the importance of ‘the mapping of variation’, which goes further than previous stuff I’ve read/talked about on just concentrating on outliers (‘positive deviance’). Such mapping, Woolcock argues, is one of the key roles for outsiders like aid agencies and INGOs. Interesting.

Just came across this great post by the ODI’s Arnaldo Pellini, summarizing a recent talk by Michael Woolcock, the World Bank’s Lead Social Development Specialist. Michael is one of the big brains pushing the ‘Doing Development Differently’ agenda. What struck me in particular is the emphasis on the importance of ‘the mapping of variation’, which goes further than previous stuff I’ve read/talked about on just concentrating on outliers (‘positive deviance’). Such mapping, Woolcock argues, is one of the key roles for outsiders like aid agencies and INGOs. Interesting.

“We are entering a new era of development which we can be called Development 2.0. Development 1.0 was concerned with technocratic reforms required to provide access to basic services such as education and health. Most countries (certainly middle income countries) have achieved that and have the infrastructures in place: policies, schools, health centers, textbooks, etc. Development 2.0 is about the state capability to make those systems work, providing good quality public services to citizens. For example, schools have been built, teachers are trained, national policies on salary and curricula are in place. So, why is it that some schools perform well and other do not perform well? Those are the questions that we need to research and answer in Development 2.0.

Development 2.0 is about multiple (and localized) solutions to development problems. A traditional approach in development is to find smart or best practices and scale them up through nation-wide policies. That approach has had mixed results. Development 2.0 is more about mapping out where public services work well and why as well as where service do not work well and why. Smart practice can still emerge but they can be interpreted to provide a variety of policy responses. This will require moving from the technocratic evidence and knowledge central to Development 1.0, to a more multidisciplinary approach to research and multiple types of evidence that can inform policy decisions aimed at improving service delivery.

Multiple sources of evidence help to deal with diversity of development problems. The new evidence generated by various types of research methods and various types of knowledge (eg, community knowledge) will produce maps of variations in service quality and delivery, which can suggest the need for multiple solutions or interventions and to draw as much as possible on local knowledge, initiatives, and various forms of capital (eg budget, social capital, human capital, etc.).

Multiple sources of evidence help to deal with diversity of development problems. The new evidence generated by various types of research methods and various types of knowledge (eg, community knowledge) will produce maps of variations in service quality and delivery, which can suggest the need for multiple solutions or interventions and to draw as much as possible on local knowledge, initiatives, and various forms of capital (eg budget, social capital, human capital, etc.).

Development 2.0 is an era where variation and uncertainty have to be accepted and embraced. It is an era where one-size-fits-all solutions will struggle to succeed and where context specific, technically sound and politically feasible solutions can have a greater chance of success.

We, development practitioners and researchers have to learn to become more modest about the extent of what we can learn and, especially, what we can suggest. We can map where bureaucracies struggle and contribute with ideas that can help segments or units of the bureaucracy to provide the services that citizen expect from them. We should avoid the temptation to suggest the solution having mapped with our work only small bits of complex political and institutional realities.

At the end of the meeting I remembered the review written by Malcolm Gladwell about the biography of Albert O. Hirschman, The Gift of Doubt: ‘The economist Albert O. Hirschman […] was a “planner,” the kind of economist who conceives of grand infrastructure projects and bold schemes. But his eye was drawn to the many ways in which plans did not turn out the way they were supposed to—to unintended consequences and perverse outcomes and the puzzling fact that the shortest line between two points is often a dead end. He understood the power of failure and had the gift of doubt.’”

Great stuff, but is it just me, or is talking about 2.0, 3.0 etc itself a bit old hat these days?

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers