Duncan Green's Blog, page 142

May 23, 2016

When/Why do countries improve the management of their natural resources? New 4 country study

Now I love Oxfam dearly but (you were expecting a ‘but’, right?) both as producers and consumers, we suffer from  TL; DR syndrome (too long; didn’t read). Not only that but we don’t always make the most of executive summaries.

TL; DR syndrome (too long; didn’t read). Not only that but we don’t always make the most of executive summaries.

Which is a shame, because some real gems often go unnoticed as a result. So allow me to pan through a recent 71 page Oxfam research report on ‘The Weak Link: The Role of local institutions in accountable natural resource management in Peru, Senegal, Ghana, and Tanzania’ and see what diamonds I can uncover.

Unsurprisingly, the report finds ‘a host of concessions and exemptions that mean the sector remains attractive to extractive companies, and compromises the ability of governments to capture revenues.’ It puts this down to a perfect political and economic storm:

‘First the implementation of structural adjustment plans in the 1980s and 1990s, which were pushed by the International Financial Institutions and which resulted from the preceding economic crisis. Second the slump in commodity prices in the 1980s and 1990s—which happened to be the same time that these countries were restructuring their economies. Finally, these countries had only recently transitioned to liberal capitalism and felt the need to guarantee the terms of the contracts they signed with extractive companies.’

So countries locked themselves into a range of bad deals for their hydrocarbons and minerals. They got the investment, but not the full benefits.

The report then looks at the various recent attempts to turn this around and finds that it’s much easier to shift the terms of contracts for new finds than existing one (fewer entrenched interests, greater civil society interest in how to spend the ‘new’ oil and gas revenues), that it’s much easier to do so in a time of rising prices than the current slump (when several good initiatives have been abandoned). And of course, whatever the progress on paper, actual implementation is a whole other thing.

Peru

Oversight mechanisms are undermined by a distorted balance of power in which executives are dominant, while parliaments and judiciaries are weak and/or coopted. Not only that, but in Tanzania and Peru, the privatization processes of structural adjustment have led to a ‘fusion of interests among the political and economic elite’ that acts as a roadblock to reform.

So what, if anything, can civil society organizations do in these situations? Here’s where the report gets interesting, and sometimes surprising.

Overall it is pretty sceptical about the results of all those ‘follow the money’ campaigns in which CSOs try to track the flow of cash from company to government and all the way down to local schools and hospitals: ‘As a process it is fraught with difficulty, while at the same time it is highly resource-intensive. Success is capricious, and even when it is achieved it does not appear to be transformative.’

Paradoxically, success is often easier to achieve where the energy is not sucked out by the time-consuming processes of transparency and accountability mechanisms, budget tracking etc. There ‘the efforts of groups working in the most constrained and repressive spaces have been the most innovative’. In Senegal, for example:

‘CSOs have been able to leverage greater civilian participation in the local budget process through the creation of “race to the top” mechanisms—such as offering certification for municipalities that agree to promote citizen participation in the budget process, even though this is not legally mandated.’

The report draws five overall lessons from its case studies of successful reform:

Structural economic factors matter. It was the mineral price boom, driven by structural features in the global

Ghana

economy, that led to effective calls for a review of the mining policy in Peru, and similar calls in Ghana and Tanzania

General political appetite for reform is most frequently manifest at election times (and other critical junctures such as leadership successions or crises), and in their aftermath.

Reforms of the sort described in this section can be promoted by both international and domestic civil society as well as by donors and other international institutions. From donor-driven changes in institutional rules in Tanzania, to the combined efforts of the International Budget Partnership and local civil society in Senegal, it is clear that different actors all constitute effective levers of change (especially when they work together).

Accountability reforms that are initially disappointing can lay the basis for subsequent progress. In Ghana and Tanzania, outcomes of institutional reforms were initially thought to be disappointing, but went on to be strengthened as a result of further pressure from civil society. I’m picking this message up in lots of conversations – a simplistic division between ‘success’ and ‘failure’ is not that helpful, when one can morph into the other over time. How do we distinguish between a total, unmitigated failure, and one that may produce unexpected success in the future?

Not all efforts at reforming accountability need to be focused on creating new institutions; in many instances, existing institutions can be effectively strengthened. i.e. activists often need to engage with the messy and uninspiring realities of existing bodies, rather than succumb to the lure of demanding shiny new institutions.

May 22, 2016

Links I Liked

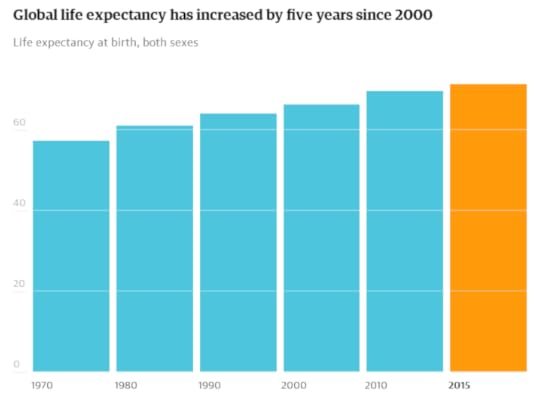

Global life expectancy has now overtaken the biblical span for the first time, up by five years since 2000, (WHO figures). Global average now 71.4 years

Big International Inequalities conference at LSE on Wednesday (25th), including rock star Thomas Piketty. I’ll be on a practitioner panel (sounds painful) in the evening

The horror of the Siemens Healthineers. The incomparable Lucy Kellaway on bad corporate rebranding (especially when accompanied by music and dance)

Top tips on maximising the impact of your research (with video clips) and making NGO videos for social media

An online poll you can really get behind: ‘Are the royal family shape-shifting lizards? (67% currently say yes) [h/t Charlie Beckett]

The limitations of Big Data – excellent from Tim Harford

ODI has a good four page backgrounder for this week’s World Humanitarian Summit. Or you can just take the Guardian quiz.

Props to IDS for making its Journal full Open Access, including a nearly 50 year back catalogue. You next ODI/Development Policy Review?

Girls are on the move. Another powerful Plan International video from my sister-in-law, Mary Matheson

May 19, 2016

How can campaigners influence the private sector? 4 lessons from the Behind the Brands campaign on Big Food

Oxfam private sector researcher/evaluation adviser

Uwe Gneiting

reflects on 3 years of a campaign to change the behavior of Big Food

behavior of Big Food

Last month we marked the third anniversary of the Oxfam’s Behind the Brands campaign with a new briefing paper that included an updated scorecard of the world’s ten largest food and beverage companies’ sustainability policies.

As an evaluator looking at Behind the Brands, I’ve been trying to distil what we can learn from the experience – were our assumptions met, why or why not, and what does this mean for future efforts to influence global corporations? Here are four lessons that I believe are among the most relevant:

Friends vs. foes – pros and cons of being a ‘critical friend’ to companies

It’s the age-old question – how collaborative or confrontational should we be towards companies that we are trying to influence? In Behind the Brands, we adopted a tone that was both problem- and solution-oriented and combined hard-hitting public campaigning with talking to (and advising) the companies. To help navigate the clashing currents of campaigning and engaging, we adopted principles to ensure our own accountability, formulated clear, non-negotiable asks, ensured transparency about our planned actions and guaranteed companies the right to respond to our published materials.

And it worked. Public campaigning got companies to the table but our ‘good faith’ approach and our willingness to engage directly helped to keep them there. Furthermore, the engagement helped us to better understand companies’ interests and constraints. But it was hard, requiring us to constantly find the right balance between being principled and pragmatic – i.e. pushing the envelope of what companies should deliver and acknowledging their constraints.

And it worked. Public campaigning got companies to the table but our ‘good faith’ approach and our willingness to engage directly helped to keep them there. Furthermore, the engagement helped us to better understand companies’ interests and constraints. But it was hard, requiring us to constantly find the right balance between being principled and pragmatic – i.e. pushing the envelope of what companies should deliver and acknowledging their constraints.

Pressure works – the amplifying effect of public campaigning

If direct engagement with companies can help us to reach productive outcomes, then why do we even need to build public pressure? Well, you do if you aim for more significant changes. In Behind the Brands, we learned that companies’ scores moved significantly more around the issues where we mobilized publicly (gender, land, climate) – or even just threatened to do so. This change is more pronounced with industry leaders (who most value their corporate reputation and brand image) and low-scoring performers (who have their poor performance highlighted and feel pressure to catch up to peers). It’s more difficult for companies in the middle of the pack although exceptions exist.

That being said, getting the attention of the media and the public can be challenging in the crowded public campaign space. In Behind the Brands, some of the most effective innovative and creative public campaign and messaging tactics included playfully referencing the brands, amplifying the voices of people affected by companies’ and their supply chains through case studies, highlighting the scorecard and its changes, doing offline stunts, and rewarding progress by companies. The focus on digital campaigning has pushed us to be more nimble and has created new alliances, for example with online campaign platforms like SumofUs or change.org, which ultimately helped us to mobilize hundreds of thousands of supporter actions.

The challenges and benefits of ranking companies

Let’s be clear – any attempt to rank companies is imperfect, requires significant investment, and comes with a certain level of simplification (even when you assess companies on 350+ indicators as in Behind the Brands). Also, scorecards like Behind the Brands are most suitable if the focus is on comparable outcome criteria (such as policy change), includes a comparable set of companies, and addresses issues for which benchmarks do not yet exist. And even then, scorecards will face challenges including the risk of greenwashing, the challenge of update fatigue, and the difficulty of reliably assessing changes in actual practice (rather than just policy).

level of simplification (even when you assess companies on 350+ indicators as in Behind the Brands). Also, scorecards like Behind the Brands are most suitable if the focus is on comparable outcome criteria (such as policy change), includes a comparable set of companies, and addresses issues for which benchmarks do not yet exist. And even then, scorecards will face challenges including the risk of greenwashing, the challenge of update fatigue, and the difficulty of reliably assessing changes in actual practice (rather than just policy).

Despite these challenges, Behind the Brands highlighted various ways through which a scorecard can contribute to a campaign’s change goals. It provided a hook and justification for public campaigning, served as an entry point to engaging with some companies, and appealed to their competitive spirits. As a benchmark, it can be used by others (e.g. investors) to evaluate companies and serve other NGOs or companies who want to adopt the criteria and indicators for their own work. Furthermore, a scorecard as used in Behind the Brands has shown to have the potential to shape internal company dynamics by creating clear information of what the company should be doing on the policy front and by showing how they stack up vis-à-vis their competitors.

Beyond the campaign – policy wins as starting, not end points

It is no secret that NGO campaigns have a more impressive track record for raising issues and achieving policy change than for tracking the implementation of those policies. Part of the reason is that implementation is complex as it involves thousands of suppliers in dozens of countries where much of the commercial activity remains hidden or undisclosed. It is simply impossible to assess implementation in the same systematic way policies can be assessed. In Behind the Brands, we share the concern that companies’ policy commitments are potentially meaningless if they are not followed through by action and if they don’t serve to contribute to broader changes at different levels of the global food system.

For Oxfam, policy change may not be a sufficient condition, but it is certainly a necessary one for broader changes within the global food system. The acknowledgment by companies’ of their responsibility for addressing problems in a systematic way signals to the wider industry, suppliers and governments that tougher issues are now on the agenda, thereby shifting the narrative around corporate responsibility and helping to trigger action by others. These early steps can become starting points for more systematic change efforts, which will have to include greater collaboration and collective approaches to structural challenges (e.g. around pricing), a revision of business models and greater attention to the most fundamental challenge: how to ensure that the women and men who produce the world’s food are earning a fair share of the value of their work.

For Oxfam, policy change may not be a sufficient condition, but it is certainly a necessary one for broader changes within the global food system. The acknowledgment by companies’ of their responsibility for addressing problems in a systematic way signals to the wider industry, suppliers and governments that tougher issues are now on the agenda, thereby shifting the narrative around corporate responsibility and helping to trigger action by others. These early steps can become starting points for more systematic change efforts, which will have to include greater collaboration and collective approaches to structural challenges (e.g. around pricing), a revision of business models and greater attention to the most fundamental challenge: how to ensure that the women and men who produce the world’s food are earning a fair share of the value of their work.

May 18, 2016

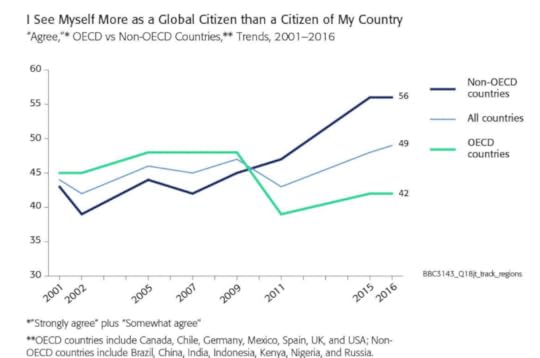

Do people identify as global or national citizens? New report suggests a tipping point, but North and South heading in opposite directions

This is interesting, and feels like it could be part of a big normative shift. According to a new report from Globescan (a polling company), across 20,000 people in 18 countries ‘more than half (51%) see themselves more as global citizens than citizens of their country, against 43 per cent who identify nationally. This is the first time since tracking began in 2001 that there is a global majority who leans this way.’

What the poll also shows is a gap opening up between North and South. The 2016 shift is driven by rapid increases in global identification in Nigeria, China, India and elsewhere (see graph, which covers only the 14 countries tracked since 2001, hence slight disparities in the numbers).

The Globescan report doesn’t speculate on the reasons for this, so here are a few random thoughts to get you started.

North and South start to diverge around 2009, which would suggest a link to the onset of the Global Financial Crisis, which hit developed economies harder than others. It would make sense for economic crisis to promote insularity and a retreat from global identity.

What’s driving the opposite, growing sense of global identity in countries such as India and China? Economic rise? Greater connection through improved media links with the rest of the world?

To what extent do the results tell us much about what people really think? Maybe it has just become more socially acceptable to be chauvinist in the North, and less so in the South, so people’s sense of what they ought to tell pollsters is the only thing that has changed? What other evidence is there that would confirm/challenge these findings? There are plenty of signs of disenchantment with globalization in the rich countries – just look at the fate of assorted trade negotiations. What evidence is there for a countervailing globophilia in China, India etc?

If this is true, it feels massive – a seismic and global normative shift in how people see themselves. What could be the long term political/economic implications of such a transformation?

One cautionary note: I am told that some people have doubts about Globescan’s methodology. That stuff is all way over my head, but is meat and drink to the nerdy end of the FP2P readership – over to you (and h/t to Barney Tallack for passing on the report)

May 17, 2016

How Change Happens: a conversation with 25 top campaigners from around the world

Spent an exhilarating morning last week with Oxfam’s ‘Campaigns and Advocacy Leadership Programme’. Must have

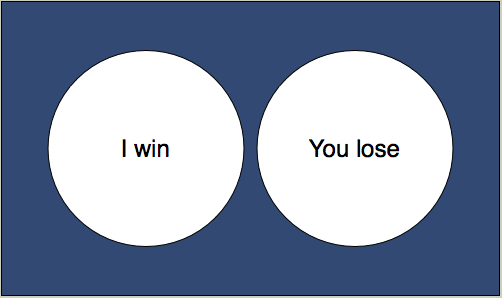

Is Power zero sum?

been at least 20 nationalities in the room, with huge experience and wisdom. The topic was How Change Happens (what else).

To give you a flavour, here are some of the topics that came up, with my takes on them:

Is power a zero sum game, i.e. empowering one group involves disempowering another?

My view: too simple. True in some cases but not in others – eg we have evidence from domestic violence work that both men and women report improved quality of life when domestic violence falls through women’s empowerment programmes. Zero sum games may attract the head bangers, but they are really hard to win – in my reformist view, we need to minimize zero sum and do our utmost to build bridges and alliances, for example by convincing the private sector that short term sacrifices on climate change will lead to long term viability.

Is there still a role for INGOs, given emerging economies, more vocal southern civil society etc?

Yes, at least three roles – focussing on global governance and public goods (tax havens, climate change etc); targeting harmful northern practices (arms trade, migration, tobacco) and support for southern change agents (via exchanges, knowledge sharing , $ when we have it). The right balance between those three is anybody’s guess, but they all matter.

The really difficult thing is sustaining change – preventing backlashes, backsliding etc once the campaign spotlight has moved on.

(still) 4 months to go….

Very true, and not something we have really got our heads round. At the level of major campaigns, good to think about exit strategy from the start, eg by setting up specialist bodies like the Bretton Woods Project or Control Arms Campaign to keep going when the big agencies lose interest. Helping southern campaigns build their ability to raise domestic resources would help with the problem of short-attention-span in Northern campaigners.

We’ve been working on indigenous health in Australia for a decade and have real successes, but how do you keep up the momentum once something has become mainstream and everyone is paying lip service to it?

Victory is tricky – it usually involves compromise, setting reformers and revolutionaries at each other’s throats. Campaigns are hardly ever long term, so at some point, you have to think about institutionalizing the gains via public bodies, however flawed, or watchdogs (see above). But just because mobilization has fallen isn’t necessarily a problem – it’s only one tactic, depending on where an issue is in the policy funnel.

How do we get beyond extractive campaigning and genuinely empower and involve ‘beneficiaries’?

This is a real challenge – national campaigning can be as extractive as global campaigning. I wish we did more in the way of action research or other people-centred approaches to bringing about change, but they often seem incompatible with our business model of short term projects, results etc. And maybe individual empowerment is just not something international NGOs will ever be good at, compared to more deeply embedded local institutions and faith organizations?

The Financial Transactions Tax is bogged down in negotiations in the EU and getting incredibly technical. How do we keep up the momentum and is it really the success we make it out to be?

It always surprises me how far we can follow issues down the policy funnel towards the extreme techie stage of final  negotiations – I’ve seen Oxfam and other NGO staff play significant roles in negotiations on trade, climate change, arms control etc etc despite not being professionally qualified in any of those topics. But at some point, we need to say, ‘this needs to be handed off to the specialists’, and we retreat to holding them to account. As for whether the FTT is a victory – potentially it is absolutely huge. It is hard to think of a more significant long-term legacy of the 2008 financial crisis than a normative shift towards accepting the idea of global taxation. Doesn’t matter if it starts small – so did the income tax, introduced in the UK in response to the Napoleonic Wars!

negotiations – I’ve seen Oxfam and other NGO staff play significant roles in negotiations on trade, climate change, arms control etc etc despite not being professionally qualified in any of those topics. But at some point, we need to say, ‘this needs to be handed off to the specialists’, and we retreat to holding them to account. As for whether the FTT is a victory – potentially it is absolutely huge. It is hard to think of a more significant long-term legacy of the 2008 financial crisis than a normative shift towards accepting the idea of global taxation. Doesn’t matter if it starts small – so did the income tax, introduced in the UK in response to the Napoleonic Wars!

How do we pursue a rights-based approach (RBA) in a context of right wing governments and attacks on civil society?

I’m a bit of a heretic on this one. RBA often gets dumbed down into supporting ‘rights holders’ (aka ‘the people’) to demand stuff from ‘duty bearers’ (usually governments). That may work if the governments are sympathetic, but in more hostile environments we need to keep a rights-based analysis, but our tactics need to be smarter – building alliances with sympathetic individuals and departments, multi-stakeholder approaches etc.

All that plus a fascinating discussion on what is failure/success, when in the longer term, you find successful change processes often have their roots in prior campaigns initially deemed failures? There is a real challenge here to the ‘fail fast’, multiple experiment, venture capitalist models of change. Going to have to think about that one.

Overall impression? I hadn’t realized just how much the content of How Change Happens reflects the best thinking already going on across Oxfam. I think the book plays two roles here – adding a more theoretical, academic foundation to these emerging ideas, and communicating them to a wider public. Alternatively, I could just be nicking other people’s ideas and taking credit for them. And no, I’m not having a poll on that one…….

May 16, 2016

The Politics of Inclusive Development: Two Books; One Title

Guest review from

Alice Evans,

Human Geography lecturer, Cambridge

The age of ‘best practice’ is over. The time of politics has come. Rather than identify and rollout effective policies, we need to understand the political struggles and coalitions by which socio-economic and political resources come to be redistributed more equitably – across classes, genders, ethnicities and spaces.

The Politics of Inclusive Development: Policy, State Capacity, and Coalition Building by Judith A. Teichman and The Politics of Inclusive Development: Interrogating the Evidence, edited by Sam Hickey, Kunal Sen, and Badru Bukenya are ideal to read in conjunction because they explore the same question through different approaches. Teichman’s comparative, historical analysis of Mexico, Indonesia, Chile and South Korea is brilliantly complemented by Hickey et al’s thematic collection (comprising chapters on the politics of accumulation, governing natural resources, service delivery, social protection, the rule of law, gender, ethnicity, the politics of aid, as well as China in Africa).

Despite this heterogeneity of authors, disciplines, sub-topics and methodologies, four themes recur throughout both texts: state capacity; elite commitment; coalition-building; and consensus.

State capacity is portrayed as fundamental to the politics of recognition, redistribution and accumulation. An effective taxation regime and proactive industrial policy, generating more and better jobs (not just funding vast numbers of microenterprises and papering over poverty with cash transfers) are cardinal for Teichman. Sen likewise underscores the importance of state provision of public goods.

State capacity is portrayed as fundamental to the politics of recognition, redistribution and accumulation. An effective taxation regime and proactive industrial policy, generating more and better jobs (not just funding vast numbers of microenterprises and papering over poverty with cash transfers) are cardinal for Teichman. Sen likewise underscores the importance of state provision of public goods.

Importantly, however, state capacity is seldom fostered by non-conflictual, technical tinkerings. To focus on the policy instruments enabling fiscal spending stabilisation in Chile, for example, is to miss the point. Technocratic management of resource rents was not enabled simply by using income from copper exports for countercyclical policy, but rather the political context from which the policy emerged and endures. It only works because the bureaucracy is competent, publicly motivated, insulated from political interference and raiding.

But why might a governing elite choose to redistribute rather than pilfer the national coffers coppers? When do turkeys vote for Christmas?

Political advantage is one reason. The selected case studies suggest that elites have often embraced pro-poor service delivery and fiscal policy in order to placate rural unrest, enhance state legitimacy, score party political points and thereby secure self-preservation. Ostensibly redistributive policies like rural road-building and expanding primary education can be intensely political, territorial, nation-building projects – as in Peru and Ethiopia. Ghana’s successful cocoa marketing is similarly a function of the underlying political economy: i.e. the relative power of cocoa producers; not policy specifics.

Even centre-right candidates may need to champion redistributive social policies in order to shore up political support – as occurred in the run up to Chile’s 2009 election. Having gained power, President Piňera then walked the talk, increasing investment in Chile’s Solidario programme.

– as occurred in the run up to Chile’s 2009 election. Having gained power, President Piňera then walked the talk, increasing investment in Chile’s Solidario programme.

Governments may also secure re-election by pledging to continue domestically popular redistributive policies, such as

Malawi’s Farm Input Subsidy Programme. Although donors initially resisted such state interference, they revised their positions upon recognition of government leadership and domestic support. To restate, the age of best practice is over; the time of politics has come… at least in Malawian agriculture.

But this raises a further question: how does state legitimacy become conditional upon approval from historically socially excluded or adversely incorporated groups? Chickens and eggs abound.

Short answer, from both texts: coalition-building.

In Chile, for instance, widespread and prolonged student protests against prohibitively expensive education not only politicised inequality, but also legitimised state-led redistribution, by cultivating consensus around the imperative for more inclusive development. The strength of this social movement enabled President Bachelet to reduce education costs, raise corporate taxes and reform the labour code (strengthening the power of the unions). Eroding Pinochet’s legacy of grotesque inequality has been a slow, incremental, deeply conflictual but ultimately successful process of state-society engagements.

The ‘Penguin Revolution’ (so called because of their uniforms) was led by middle-class students. As Teichman documents, middle-class groups have also been instrumental to democratisation and redistribution in South Korea: allying with human rights groups and unions, publicly contesting inequalities and being an empathetic bureaucracy, concerned about social welfare. She further speculates that middle-class groups would be more likely to support redistributive policies if their own positions were less precarious. [I’m not sure there’s enough evidence to support that point, however – American health insurance being an obvious counter-example (see here and here)].

All fascinating, but I found four surprising omissions.

All fascinating, but I found four surprising omissions.

First, the books predominantly focus on governing elites and their reasons for acting. Why so little attention to the other end of the social contract- how marginalised people gain self-esteem; disavow demeaning stereotypes; and foster wider support for equality, including building coalitions with sympathisers among advantaged groups and political elites? There’s no shortage of literature on this (as David Hudson and I have found in writing our paper on ideas).

Second, I was surprised that two mighty texts on politics do not differentiate between different kinds of ideas: internalised ideologies and norm perceptions. That is to contrast individuals’ unquestioned acceptance of the status quo and their beliefs about what others think and do. For instance, even if people do believe they are entitled to better health services they might not challenge inequalities if they lack confidence in the possibility of social change, if they believe the state will only ignore them or react violently. Likewise, if women believe the police will be unsympathetic they may be reluctant to report local corruption or gender-based violence.

Third, most of the chapters seem to treat developing countries as closed systems, and pay limited attention to material and ideological global flows. While Hickey et al include two chapters on international relations (the politics of aid, and China in Africa), the rest of the collection scarcely mentioned aid politics, the MDGs, global value chains, or regional norms and networking.

This is odd. In focusing on developing country case studies, the texts could be interpreted as saying that the major barriers to inclusive development lie within these countries. Clearly no text can cover everything but in presenting themselves as guides to the politics of inclusive developments and then omitting global public goods (like international migration and intellectual property, climate, trade policies, financial transparency etc.), I worry that my students might be led to disregard geopolitics.

Fourth, the texts seem to disregard the need to think and work politically. When trying to support pro-poor reform in specific locales, what good are general theories about how elites come to adopt long-term visions for Development? This relates to a much wider problem in academia. Rather than research then disseminate big ideas, might an iterative, collaborative process between researchers and Development practitioners be more effective? – as eloquently suggested in Desai and Woolcock’s chapter, then further detailed by Matt Andrews, in relation to judicial sector change in Mozambique.

Having thoroughly enjoyed both texts, I would love to hear more from the authors on these points.

May 15, 2016

Links I Liked

Oxfam Intermon use a hidden camera to record the reactions to paying more for your beer (and link it to tax dodging). Simple but effective

Update on what I’m up to. Speaking at Manchester (tomorrow) and LSE (25th May). I’m also putting all vlogs up on youtube, and all FP2P posts are now going up on Medium.

I presume it’s in my interest for an FP2P reader to be my new boss? Oxfam GB Director Of Campaigns, Policy &  Influencing. Closing date 31st May

Influencing. Closing date 31st May

Guy Verhofstadt comprehensively destroys Europe’s refugee ‘policy’ [h/t Alex Evans]

The most cited publications in the social sciences (according to Google Scholar). Kuhn (Scientific Revolutions) comes top of a long list of clever chaps (no women in top 25)

Who becomes a terrorist & why? Summary of the debate between French scholars on the relative weight of different factors (Islam, alienation, generational revolt)

Forget logframes, please welcome the Searchframe, from Matt Andrews and the Doing Development Differently crew. Will it catch on?

The Anti-Corruption Summit generated lots of good analysis as well as some awkward moments

Do donors want zero tolerance of corruption or results? Because there are trade-offs. Alina Rocha Menocal and Heather Marquette explain

Do donors want zero tolerance of corruption or results? Because there are trade-offs. Alina Rocha Menocal and Heather Marquette explain

Great overview of the state of the anti-corruption movement and evidence, from Alan Hudson

Damning verdict and summary of the Summit outcomes from the Tax Justice Network. CGD disagrees, finding stuff to applaud on open contracting (Charles Kenny) and UK decision to publish list of beneficial owners of companies who own property in UK or bid for government business (Owen Barder).

And last week was the 10th anniversary of the legendary mistaken identity interview on the BBC. Enjoy the way Guy Goma, who had come in for a job interview, rose to the challenge of being interviewed on live TV about the internet. Pure class. [h/t Ian Birrell]

May 12, 2016

How to read and comment on a draft paper – your suggestions please

Today’s vlog (I’ll be coming back to you in a few weeks to ask whether these are worth doing)

I spend a lot of time commenting on draft research and policy papers, both for Oxfam and beyond. So I put down some ideas  on how I approach it, got some great input from Oxfam Research Team colleagues, and now we want to ask you to chip. Then we’ll publish a revised version in our series of research guidelines. Although this is based on NGO and aid agency reports, I suspect a lot of this goes for academic papers too.

on how I approach it, got some great input from Oxfam Research Team colleagues, and now we want to ask you to chip. Then we’ll publish a revised version in our series of research guidelines. Although this is based on NGO and aid agency reports, I suspect a lot of this goes for academic papers too.

How to approach a draft: Please try and put yourself in the shoes of the target audience and think what would interest or inspire them. Don’t go into internal lobbyist mode, combing through the document looking for/shoehorning in references to your particular hobbyhorse!

I read the paper as I would speed read the final article: the exec sum first, then the conclusion, then the top and tail of each chapter. I try to focus my comments on those sections because they are (by far) the most important in terms of impact.

But you do need to read the whole thing. Is the paper internally consistent? Have any nuggets (killer facts, case studies, telling graphics, genuinely surprising or new findings) failed to make it to the exec sum – a common crime in NGO papers?

As a reader, you are also likely to be better placed than the author to point out places where some extra narrative would help. I call it ‘hand holding’ – suggesting linking text between paras to improve the flow, or explaining why a certain piece of analysis is significant and worth a reader’s time – often underplayed by authors who are so obsessed with their subject, that they can’t imagine why anyone would find it boring!

Is the good stuff at the top? Let’s assume a large percentage of readers don’t read all the way through to the end. You need to make sure the best, most powerful ideas and arguments are up front, preferably in an executive summary, but if not, at the top of the paper. And then repeat them regularly throughout the text.

Remember what the paper is for and don’t try and expand its remit: If possible, take a look at the original terms of reference for the paper. They should set out the audience and purpose. That can help you avoid giving the classic unhelpful comment ‘it’s too long, needs cuts, and here’s another 10 issues you need to cover’! Depending on whether it’s at the wonky end of the spectrum (research paper) or the more popular end (policy paper), there will be a different balance of the need for rigour and accessibility, but both matter in all cases.

Remember what the paper is for and don’t try and expand its remit: If possible, take a look at the original terms of reference for the paper. They should set out the audience and purpose. That can help you avoid giving the classic unhelpful comment ‘it’s too long, needs cuts, and here’s another 10 issues you need to cover’! Depending on whether it’s at the wonky end of the spectrum (research paper) or the more popular end (policy paper), there will be a different balance of the need for rigour and accessibility, but both matter in all cases.

Think about what is not there. This is difficult but can be really useful – it’s easy to critique what’s in front of you, but it is often more helpful to stand back and identify what is missing – in terms of arguments, approaches, or sources. As well as stepping back, try to look sideways – the author is likely to be a specialist, up to their neck in the detail of a particular subject. Is there anything they could usefully import (whether as content or analogy) from different issues or disciplines?

Style and Language matter: A personal bugbear – a lot of NGO papers are really badly written. Full of impenetrable jargon, deadened by the passive tense, and/or shrill in tone ‘the IMF must do X, Y, Z’. That turns off potential readers and greatly reducec a paper’s impact. Here’s some good advice on writing for impact. Dealing with bad writing is tricky, especially if the writer does not have English as a first language, but in my experience, people are usually grateful for specific suggestions and edits. If rewriting the whole paper is not feasible, concentrate on making the executive summary accessible.

How clear are the ‘so whats’? A common weakness is papers that are strong on diagnosis and exposition of the problem, but weak on what to do about it (someone once caricatured such work as ‘bad sxxt, facty, facty’ papers). Does the paper have specific, well argued suggestions for how to improve things or are the recommendations bland and generic? (see How to write the recommendations to a report on almost anything).

Feeding Back

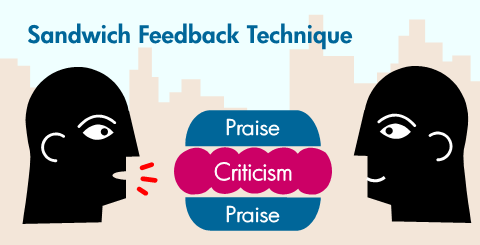

Be kind: Once you’ve scribbled all over the paper, it’s time to feed back to the author. Take a deep breath. However brilliant/damning your critique, start by reminding yourself that there is a human being on the other end of this email. They have tried their best, even if the result needs work. You need to help them, not cast them into despair. Maybe talk to them face to face rather than just send an email?

Cue the infamous sxxt sandwich. Start off saying what you like about the paper, then what could be strengthened, but

Seems to be a word missing……

finish off by stressing what is worthwhile. This needn’t be phoney – there is usually something to applaud in any piece or work. And even if people know what you are doing (a civil servant once told me ‘everything above the ‘but’ is bxxxxcks’), it still eases the pain and makes it easier to absorb and respond to criticism.

Be specific: Don’t just say ‘there’s some good stuff in here’. Give examples: a particular sentence that is nicely written, a particularly powerful paragraph, a quote judiciously used. Knowing what works (and hence what to retain) can be helpful as well as good for (battered) authorial morale. Even more so when you suggest improvements. To a harassed author on a deadline, comments like ‘needs more on gender’, or ‘you should read Amartya Sen’ are more likely to drive them to self harm than write a better paper. Specific text changes only, if possible.

Receiving Feedback

Being on the receiving end of feedback can be bruising, especially when people don’t follow this kind of advice (I’ve got a few scars). If you feel your hackles rising, don’t get defensive, don’t hit ‘reply’. Probably worth sleeping on it before reacting. Remember that this is free consultancy, after all, and you get to choose which advice to respond to. If there are multiple commentators, so much the better – more advice, and easier to pick and choose what to take on board.

And yes, all this takes time, so it’s worth first making sure that the author really wants your comments, and getting them in ahead of deadline.

OK, over to you – what have we missed?

May 11, 2016

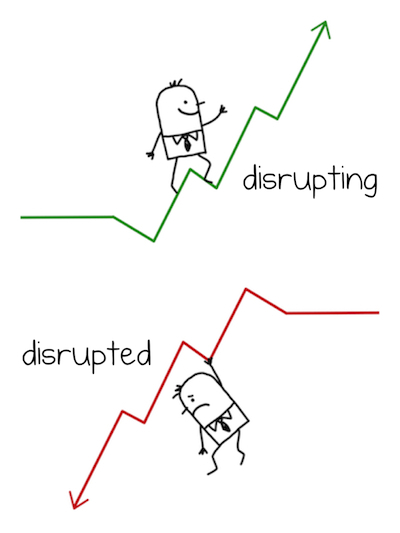

Is Disruption a good thing? Let’s ask Southern Civil Society leaders for a change.

Disruption is cool in the development chattersphere right now, and that may not be a good thing – what if the thing being disrupted is actually useful or valuable? Do you want your marriage/home/body/ cat disrupted? Thought not. Organizations doing good work don’t necessarily have to be innovative (what about practice makes perfect?); good partners don’t have to be new and funky. Above all, poor people and communities often have way too much insecurity in their lives already (vulnerability to disruption is a defining characteristic of being poor) and don’t need the aid business adding to it by going all disruptive on them.

Disruption is cool in the development chattersphere right now, and that may not be a good thing – what if the thing being disrupted is actually useful or valuable? Do you want your marriage/home/body/ cat disrupted? Thought not. Organizations doing good work don’t necessarily have to be innovative (what about practice makes perfect?); good partners don’t have to be new and funky. Above all, poor people and communities often have way too much insecurity in their lives already (vulnerability to disruption is a defining characteristic of being poor) and don’t need the aid business adding to it by going all disruptive on them.

Which means I welcomed the recent IIED report on ‘Getting Good at Disruption in an Uncertain World’. For a start, it goes in for its own brand of disruption by being based on interviews with a range of southern NGO leaders. The interviewees, quoted at length, give powerful insights into the warts-and-all world of southern NGOs – staff turnover, fickle governments and donors, charismatic but sometimes flakey leaders. The overall picture that emerges is one of seat-of-the-pants survival and constant churn – more white water rafting than supertanker.

Here’s some paras from the summary:

Too often, key players in the international development community, including development agencies and international NGOs based in the North, are themselves disruptors of Southern NGOs’ efforts to tackle poverty and deliver positive outcomes. Interviewees gave numerous examples, such as ‘cut and shut’ changes in donor policy, the disempowering side effects of tendering requirements for consortia, and reluctance on the part of international NGOs to share scarce funding for organisational development with their Southern partners.

The negative impacts of both internal and external disruption are more acutely felt in regions and countries where very few NGOs have endowments or reserves to cushion operating budgets during periods of uncertainty. The frequency and intensity of disruption from two sources in particular stood out for our Southern interviewees: funding turbulence, with its associated financial uncertainty; and rapidly changing (and often shrinking) operating spaces for civil society, even among democracies of the global South.

The negative impacts of both internal and external disruption are more acutely felt in regions and countries where very few NGOs have endowments or reserves to cushion operating budgets during periods of uncertainty. The frequency and intensity of disruption from two sources in particular stood out for our Southern interviewees: funding turbulence, with its associated financial uncertainty; and rapidly changing (and often shrinking) operating spaces for civil society, even among democracies of the global South.

Whether understood as sudden shocks or a general awareness of impending change, disruptors are catalysts for organisational change. This paper details the range of approaches interviewees have adopted for anticipating, engaging with, and responding to disruption. Interviewees described how disruptors can trigger re-thinking of organisational missions, business models, and ways of working; they described the roles of their leaders both as disruptors themselves and, at their best, as key players in the avoidance of negative disruption. Several highlighted their commitment to continually refreshing their organisational capabilities, for example, by bringing in private-sector experience or technological know-how.

Interviewees were asked to consider the implications of their experiences in managing disruptive change for donors and international NGOs.

Northern-based international NGOs (INGOs) must step up efforts to expand the effective operating space for civil society in the South.

Through their own operating practices, they need more actively to nurture innovation whilst continuing to value resilience and adaptive capacity.

They need to consider the value of — and avenues for — unrestricted financing to bolster organisational development, and the skills and capabilities needed to turn disruption into a creative force for innovation and sustainable development.

And here’s a taster of the interview material:

On disruption as a positive force (James Taylor, South Africa).

Disruption is life! Disruption connotes unexpected things that upset our perfect systems and plans. But the way

What if someone moves the bowl, or it’s vodka, not water?

that I relate to the term is very closely related to my attempts to understand development itself. When our organisation was formed, our mission was around trying to facilitate ‘development’. Development is the life-force that carries all life onward. When you start looking at the patterns, stages and phases that all living systems move through, and trying to understand why we get ourselves stuck, you start recognising a number of things. At moments of stuck-ness, disruption is what brings the energy for movement again. It is a force that keeps things dynamic, forming and reforming. I view disruptors as very, very crucial drivers of development. Often we respond to change in a negative way. But it is a very important part of the tension that develops between the striving for equilibrium and the force for disruption. It isn’t about trying to fix that — it is about working with it.

And from Masood Ul Mulk, Pakistan

When I walk into an organisation and I see chaos I am very happy, because I know that things are getting done. When I walk in and see everything very slick, I worry that everything has come to a standstill. In an uncertain world, if you try ‘perfect management systems’, they may just fall apart

On Donor Disruption(Daisy Kambalame, Malawi)

In most NGOs I have worked with, the biggest source of change is in the policy of donor countries. If policy changes in the UK or the US, people have to change their whole approach and/or organisational structure.

Sometimes it comes in themes. For example, there was a time when HIV/AIDs was the key theme, and at some point it didn’t matter what you were doing — you had to have something in that area. There was another time when GMOS were the big thing, so there’s lots of push for NGOs to have some programme to address that. You’re always on the lookout, and have to adjust. Because most NGOs don’t have secure sources of funding, they have to regroup and reorganise themselves [according to these trends]

On Policy Fads and Distrust (Shahid Zia, Pakistan)

Many Southern NGOs were quite late to join struggles against climate change. There was resistance in the beginning — [a feeling] that climate change is a Northern, not a Southern, agenda. You might have heard many different voices from the South — if not from NGOs, then from media/government — that we have so many other things to work on; that climate change is not our first priority, whether mitigation or adaptation. Many NGOs held the same view; they felt that food security, poverty, education, access to clean drinking water — all these issues had suddenly gone on the back burner, with climate change becoming the priority. There was a feeling that temperature increase will not bring that much hardship to the South, because the South already experiences high temperatures — that climate change would cause much more trouble for the North.

What I’m saying is that frequent changes in positions from the North — without engaging Southern partners — [had] created a deficit of trust.

May 10, 2016

The Global Beneficial Ownership Register: a new approach to fighting corruption by combining political advocacy with technology

A second post on corruption ahead of tomorrow’s summit. Activists are often more concerned with how they see  the world than with understanding how others see it, but understanding what motivates and incentivises others is crucial to building coalitions for change. Transparency campaigner David McNair describes one such example, a wonky-but-important demand for a Global Beneficial Ownership Register to curb tax evasion.

the world than with understanding how others see it, but understanding what motivates and incentivises others is crucial to building coalitions for change. Transparency campaigner David McNair describes one such example, a wonky-but-important demand for a Global Beneficial Ownership Register to curb tax evasion.

After more than a decade of campaigning to open up tax secrecy in offshore (and on-shore) centres, we can claim some success. But not all of that can be attributed to campaigners.

Ahead of the financial crisis, our arguments didn’t get much of a hearing. The crash changed all that. Post 2008, when countries the world over were chasing revenues, they were no longer so willing to turn a blind eye to offshore evasion – and that – with a push from campaigners – led more than 80 governments to automatically share tax information.

The next fight lies in pursuing information on the true ownership of companies and other legal entities. The Panama Papers have shown us how the establishment of anonymous companies happens on an industrial scale. These companies are routinely used to channel ill-gotten gains away from the oversight of governments and regulators. Here progress has been less impressive – unsurprising given the cast of those among the global elite who are implicated.

The next fight lies in pursuing information on the true ownership of companies and other legal entities. The Panama Papers have shown us how the establishment of anonymous companies happens on an industrial scale. These companies are routinely used to channel ill-gotten gains away from the oversight of governments and regulators. Here progress has been less impressive – unsurprising given the cast of those among the global elite who are implicated.

The gold standard here is public disclosure of the true ‘beneficial ownership’ of companies and trusts. Groups like Global Witness, Oxfam, ONE, Christian Aid, Transparency International and others have been pushing this for a long time – securing commitments from the UK, Netherlands, Australia, South Africa and Nigeria.

But the European response in the Anti-Money Laundering Directive has been half baked, and the US has shown little willingness to police the problem. Even the UK, as a first mover, actively pushed for trusts to be left off the table in Europe. And this month, offshore centres like Cayman Islands celebrated the UK’s leniency when Prime Minister David Cameron congratulated them for how far they have come, despite the fact that their proposal falls far short of public transparency. These loopholes risk creating a game of whack-a-mole – where the problem gets solved and then pops up somewhere else.

In response, an unusual coalition of business leaders, NGOs, and a tech startup have launched a new initiative to deal with the problem in a very different way: the Global Beneficial Ownership Register.

with the problem in a very different way: the Global Beneficial Ownership Register.

Grand corruption is a networked problem; to fight it we need a networked solution. Often money launderers will establish a firm in one country, which is, in turn, owned by another company or trust in another country. These legal structures are like russian dolls. Pretty soon it becomes very very difficult to track who owns what.

This register would be the ‘Google search’ of who owns legal entities. Developed by Opencorporates, the largest open database of companies with 99 million firms on its books, this tool aims to enable investigators and corruption fighters to follow the money and see the connections between ownership of companies and trusts the world over.

It removes the technical barrier for governments (e.g. of smaller countries) to address company secrecy by providing a tech tool (like gmail) that could be taken and adapted by a country to its own circumstances. This removes the argument that the problem is too difficult or costly to solve.

But for success, we need to build and align incentives not just for those that care about corruption, but also for public institutions and business.

Here the critical piece is helping to reduce the burden of risk management and due diligence for accessing public procurement, export credit or for becoming a supplier to a large multinational. Businesses want to know who they are doing business with, to reduce the risk of fraud, failed contracts or investments. They don’t want to inadvertently do business with politically exposed persons (which can now result in hefty penalties and ongoing drops in stock value).

Here the critical piece is helping to reduce the burden of risk management and due diligence for accessing public procurement, export credit or for becoming a supplier to a large multinational. Businesses want to know who they are doing business with, to reduce the risk of fraud, failed contracts or investments. They don’t want to inadvertently do business with politically exposed persons (which can now result in hefty penalties and ongoing drops in stock value).

Institutions and businesses can use the register as one step in a procurement process, requiring bidders to register their ownership. This can be combined with contractual liabilities for fraudulent disclosure while allowing the ownership information to be subject to checks by investigators, journalists, civil society and other interested parties due to it being public.

This in turn, provides an incentive for others to register voluntarily. Their data will integrate with the data aggregated from all public registers of beneficial ownership and information that can also be “scraped” from filings companies make in other kinds of registers and regulators.

Making the register work for business means addressing data quality and being able to prove the benefits of network effects – that a much wider set of people can alert you to a political connection through their access to the information. Donors too have expressed an interest in using the tool to increase transparency and manage risk around their procurement.

As this coalition develops the register, working with all the different types of users – governments, international  institutions, businesses, civil society, journalists – will be critical to designing a platform that plays its role in getting rid of company and trust secrecy.

institutions, businesses, civil society, journalists – will be critical to designing a platform that plays its role in getting rid of company and trust secrecy.

But it is also critical for building the kind of coalition of unusual suspects that can make the case that this kind of policy is needed, is feasible and will make a difference.

David McNair is Policy Director for Transparency at The ONE Campaign. @david_mcnair

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers