Duncan Green's Blog, page 139

July 4, 2016

Want to empower women? Digital Financial Services are the way to go!

Sophie Romana (left)

and

Shelley Spencer

(right)  report back from the June 8 high level

report back from the June 8 high level  roundtable organized by NetHope and USAID, which brought together mobile banking and gender champions to reflect on how Digital Financial Services (“DFS”) can galvanize women’s empowerment.

roundtable organized by NetHope and USAID, which brought together mobile banking and gender champions to reflect on how Digital Financial Services (“DFS”) can galvanize women’s empowerment.

Women’s empowerment is often measured by their access to resources and ability to make decisions over how they are used. Recent evidence shows that DFS delivered through mobile phones deserves solid As against each metric. This is not just hopeful musing by us as two empowered women with banking apps on our mobile phones. It is the consensus of a cross section of thought leaders with a seat at the table in Washington including USAID, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Better than Cash Alliance and UNCDF, CGAP, and Women for Women International, as well as our own organizations, Oxfam and NetHope. We recently spent a morning reflecting on rigorous academic and implementation research on DFS use by women — all to be published soon — and pathways to close the gender gap in DFS product use.

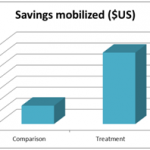

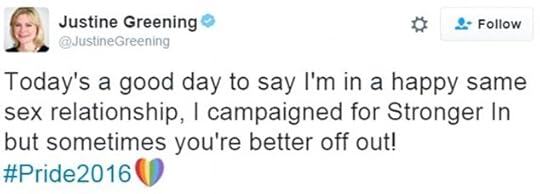

Oxfam has long known that women play a central role in financing family and community needs. What we are now finding is that DFS tools can enhance their role. To study the impact of DFS on Saving for Change (“SfC”) savings groups in Senegal, Oxfam divided up 210 SfC groups (over 5,000 women) into 2 cohorts: one who participated in the project and the other as a comparison set. Women who participated in the pilot saved and borrowed more than the comparison groups. The differences are not marginal. There is a significant difference in savings.

Graphs source: Saving for Change Mobile Banking, First Assessment & Learning Review, March 2016, Oxfam America

Beyond financial transactions, mastering basic operations such as making a phone call, sending a text message, and performing a transaction brought pride to these women and gave them a sense of belonging in a formal financial system.

The technology is simple, the demand is known, so why aren’t DFS more widely used by women in developing economies?

Obstacles still exist. Take a look at Women for Women International’s core empowerment program which includes  education and training modules in using financial services: efforts to use DFS were challenging in the DRC and Rwanda due to the paucity of rural mobile money agents. Furthermore, women felt that a 10% transaction fee was too high a cost to pay to access money they had received: they felt that accessing their own money should be free.

education and training modules in using financial services: efforts to use DFS were challenging in the DRC and Rwanda due to the paucity of rural mobile money agents. Furthermore, women felt that a 10% transaction fee was too high a cost to pay to access money they had received: they felt that accessing their own money should be free.

Increasingly there are multiple success stories from m-pesa to CARE’s Linking for Change and other popular services. Yet even with this growing body of evidence, we still don’t see massive adoption despite growing cell phone penetration rates, cheaper handsets, better technology, interest from financial institutions and mobile network operators. And the question we tried hard to answer remains – why?

Would a mobile phone be better?

What can we collectively do, as service providers, donors, private sector and civil society actors, and governments to make the promise of DFS come true for millions of underserved women in the world?

Here are some hypotheses about the kinds of actions we could take globally to unleash the feminist potential of DFS:

Can we tackle social norms that inhibit women’s participation in services (using successful approaches from other sectors be they education, health or other) and apply them to DFS to overcome resistance to women’s access to and use of DFS products? As we do with gender work, for instance, approaches could explore how to include men and women together in DFS training; or taking a leaf from drawn from other training techniques by showcasing benefits to the entire family (and not the sole user) through education and awareness; games are another avenue to make a complex product easily understandable, like the climate change games, for instance.

Will mandating use of digital payments by government (for social protection payments) or salary transfers to women mainstream DFS use and cement its value?

Can we ensure product review and adaptation are relevant to the diverse segment of women’s financial services’ needs (i.e. smallholder farmers with irregular income, garment workers with regular salaried payments). For example, factory workers and temporary economic migrants need to have access to affordable payment transfers to send money to their families at home and to save a few dollars as emergency cushions for themselves.

Will expanding the number of DFS acceptance points by including small merchants and other locations where women routinely conduct day-to-day transactions actually increase adoption of DFS? There are too few points of sale where women can use their e-wallets. Instead, most of the time, they have to transform physical cash into digital cash and then back into physical cash to be spent. They are stuck in a loop of physical cash.

Can we better analyze women’s price sensitivity of women to mobile money transaction fees, looking at the complex and diverse women market segments that may need lower transaction costs to justify use on small purchases and be more fit for purposes such as paying school fees?

How can we influence service providers to adapt their pricing schemes to create incentives for women who already are much better credit risks than men, therefore incentivizing them to become early adopters? Saving for Change has demonstrated that women members have an almost perfect repayment rate on their loans: how can we work with financial institutions so they recognize this fact and create products with better terms, instead of penalizing women with higher interest rates and collateral requirements?

We don’t know the answers yet, and it may be a combination of all the above and other factors too. What we do know is that joining forces to get the right kinds of DFS into the hands of women could have a big impact on their lives and the lives of their daughters.

July 3, 2016

Links I Liked

The whole Fragile States discussion came a lot closer to home last week (power vacuums, formal v informal power,  unstable leadership, fragmented patronage-based party systems, even the role of elite boarding schools……).

unstable leadership, fragmented patronage-based party systems, even the role of elite boarding schools……).

Why oh why did the Remain campaign reject this poster? We deserve an answer.

As a public service, Buzzfeed has pulled together all the best Brexit tweets of the last week. They are a spectacularly wonderful timesuck, but, like reading Private Eye, leave you feeling dirtied and depressed.

And finally on Brexit, the inevitable Downfall video – rather good, I thought

Faced with bonkers politics, my twitter feed seemed to take refuge in technology

Just in case blockchain is as important as people say (could it make banks largely redundant? Please say yes), here’s  a handy explainer

a handy explainer

While we’re on technology, nice (if rambling) piece on ‘Apple man’ v tech for real people (eg with kids, relatives etc)

Got a candidate for the 100 most inspiring social tech innovations from around the globe? Here’s how to enter the competition

Meanwhile back out there in the real world, in the 50 yrs since its independence, Botswana has gone from per capita GDP of $83 to $7300 – 15% more than South Africa. And almost all on the basis of diamonds. Resource curse anyone?

And everyone needs some good news at the moment, so how about ‘Ozone layer hole appears to be healing, scientists say’. Those pesky experts again.

June 30, 2016

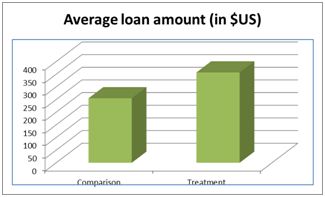

Book Review: Eden 2.0: Climate Change and the Search for a 21st Century Myth, by Alex Evans

In his new book, Eden 2.0 (just 68 pages, published today, but currently only available on Kindle, which is bad news for technophobes and  tree killers like me, or people who dislike Amazon), Alex Evans asks a question that has been uppermost in every Remainer’s mind in recent days ‘if evidence and rational arguments aren’t enough, then what is?’ He is talking about climate change, but his thoughts are every bit as relevant to the post-Brexit debate.

tree killers like me, or people who dislike Amazon), Alex Evans asks a question that has been uppermost in every Remainer’s mind in recent days ‘if evidence and rational arguments aren’t enough, then what is?’ He is talking about climate change, but his thoughts are every bit as relevant to the post-Brexit debate.

Alex is an ex DFID ‘Spad’ (Special Adviser), turned academic, but here he is saying that all the cunning plans and clever tricks of the policy wonk aren’t anywhere near enough, when it comes to a massive, species-threatening event like climate change:

‘If we’re to overcome an issue as enormous as climate change, then we need to look far beyond policymakers and pie charts. Instead, I’ve come to believe that we need to build the kind of mass movement that has in the past ended slavery, fought for civil rights, or won the write-off of billions of dollars of third world debt.

To animate movements on this scale, we need powerfully resonant stories, and they need to be stories that unite rather than divide us. “Enemy narratives” that tell us why climate change is all the fault of Exxon or Saudi Arabia won’t cut it. Instead, we need stories that help us to see the world and ourselves in a very different way.

Not so long ago, our society was rich in these kinds of stories, and we called them myths. Today, though, we have a myth gap. Religious observance is declining steadily. So is trust in leaders and institutions of all kinds. Almost unnoticed, we have slowly lost the old stories that used to bring us together and help us to make sense of the world. In their place, new “anti-myths” are flourishing – that we are what we buy, for instance, or that the world is heading rapidly towards environmental collapse and there’s not a thing we can do about it.’

Better be both?

In response, he argues that we need to fill the myth gap with a particular set of stories geared to this century’s challenges:

‘We need myths that get us to think of ourselves as part of a larger us; that situate us in a longer now, with much greater awareness of the deep past and deep future; and that help us to imagine a different good life, with less emphasis on material consumption and more on wellbeing, happiness and (most of all) a sense of larger purpose.’

Those myths need to speak both of redemption and restoration, ‘how we can atone for what we’ve done and start to make things right again.’

As the quotes hopefully show, the writing is delightful: a page turning combination of telling anecdotes, personal reflection, interviews and intellectual fireworks, drawing on non-usual suspect disciplines like cultural studies, theology and marketing, all laced with pop culture references.

Both personally, and in his analysis, he’s big on religion, historically the greatest mythmaker of all. He argues for ‘repairing the broken Covenant’ as a core myth for the climate change movement.

It’s all deliciously written, and I was duly seduced, but as I got towards the concluding ‘so whats’ section, which sets out ‘ten ideas for how individuals, citizens, activists, and communities can help to put our twenty-first century myths into practice’ doubts started to bubble up. I found some of the 10 ideas underwhelming and/or a bit familiar compared to the grand sweep of the book – mindfulness, rejecting consumerism, exercising citizenship, firing up religious groups, making the most of critical junctures and so on.

And is there really a myth gap? After all, there are remarkably effective mythmakers in Hollywood who have been churning out powerful stories about climate change and environmental struggle and redemption for decades – why haven’t they had more impact?

have been churning out powerful stories about climate change and environmental struggle and redemption for decades – why haven’t they had more impact?

The whole myths/values approach has also been around for a while, whether in the discussion on ‘framing’ or Tom Crompton’s Common Cause initiative, which is a sort of secular version of Eden 2.0. The former UK government climate czar John Ashton has also ploughed a similar furrow, with similar classical and religious overtones. None of them have made much headway beyond the already converted, as far as I can tell.

Alex’s myths are also too free-floating. Yes, you need animating myths, but he needs to pay more attention to the social basis of mass movements, because just developing myths is not going to be enough. He lauds the Jubilee debt campaign as a model, but it involved no significant cost to Western societies, certainly nothing compared to rejecting consumerism. History suggests that mass movements are almost always connected to the interests of some important social group which has become sufficiently coordinated and organised to coalesce into effective coalitions. For climate change this is the biggest problem; in Ulrich Beck’s words: “…can intangible, universal afflictions be organized politically at all? Is ‘everyone’ capable of being a political subject?….Is globalized and universal victimization a reason not to take notice of problem situations or to do so only indirectly, to shift them onto others?”.

Don’t get me wrong, it is precisely because the book is so good that it got me thinking along these lines. It’s an injection of energy and originality into an often stale and dessicated debate, offering a new way of seeing both problems and solutions. Read it and tell me what you think.

June 29, 2016

What’s the likely impact of Brexit on development, aid and Oxfam? Any opportunities amid the gloom?

Following on Tuesday’s retrospective ‘how did this happen?’ piece, some thoughts on the future, starting

So does ‘crisis ‘ really equal ‘danger’ + ‘opportunity’?

wide (development in general) then narrowing down to the aid business, and all the way to Oxfam/INGOs. All highly tentative, subject to correction etc in the coming days. One big assumption: I’m assuming that Brexit actually goes ahead. And one pleasant surprise – there are a few opportunities as well as a lot of risks in the post-Brexit confusion.

Development, output and trade: Unless you are an extreme anti-capitalist, it’s hard to see an upside in $3 trillion dollars being wiped off global markets in the two days after the vote, or the coming years of uncertainty and instability in the UK, with plenty of potential for contagion to the EU (a great unravelling?) and beyond. See briefing from ODI’s Phyllis Papadavid for more.

The implications for the trading system are messy. A Brexit UK will presumably have to negotiate both a spate of bilateral trade deals to replace EU-led ones such as the Economic Partnership Agreements with Europe’s former colonies, and entry to the WTO as an independent player (it’s been represented by the EU up to now). More from Owen Barder on the implications for the UK’s trading partners in Africa and elsewhere.

the view from Germany

Aid: At first sight, this looks like big trouble for 0.7 – many of the Leavers are just as hostile to internationalism and aid as they are to the EU. A Brexit government is likely to find itself in urgent need of cash, so overturning Britain’s legal commitment to 0.7 would look like like an easy target. That’s certainly Owen’s view. So I was surprised (and reassured) by the more optimistic analysis by Oxfam’s political liaison guy, Tim Livesey. He argues convincingly that any Brexit government will be keen to show that Britain is not turning its back on the world. The legal commitment to 0.7 means that any attempt to cut aid would require a high profile decision in parliament, where a recent debate showed just how much support for aid exists, despite the best efforts of the Daily Mail. Of the two front runners to succeed David Cameron, Boris Johnson is a cosmopolitan internationalist, while Teresa May is famous for telling the Tories to shed their image as ‘the nasty party’. For Party read nasty Country – Britain’s reputation has been deeply damaged by Brexit, and its aid programme could help restore it.

A lot of UK aid currently goes through the EU, and that would become purely bilateral UK aid after a Brexit. That could give opportunities for DFID to do more in the way of innovation and accountability (although on the other hand, if DFID chooses to do bad or dumb stuff, it will have more money to do it with).

But in at least two other areas, Brexit is just plain bad news. At the time of writing, Brexit has devalued  the pound by over 10%, massively cutting the real value of British aid. Second, the entire British political machine will be consumed for years by Brexit negotiations, so you can kiss goodbye to a lot of British leadership on everything from nutrition to women’s rights, although DFID’s global role will hopefully continue, as Brexit talks drag on in Brussels.

the pound by over 10%, massively cutting the real value of British aid. Second, the entire British political machine will be consumed for years by Brexit negotiations, so you can kiss goodbye to a lot of British leadership on everything from nutrition to women’s rights, although DFID’s global role will hopefully continue, as Brexit talks drag on in Brussels.

The British aid business: Will the anomalously dynamic UK aid cluster survive? It will have a series of blows to its funding (eg European research grants will become harder to access), bandwidth in Whitehall will shrink, and in any case, Britain’s international voice will be diminished in Brussels and beyond.

Oxfam/other UK based INGOs: There are already serious financial consequences from the drop in the value of the pound – Oxfam may need to dig into its reserves to minimise the damage to its partners. The future contains further risks: a post-Brexit recession in the UK would inevitably hit our ability to raise funds from the public. Whether or not we can continue to access EU funding (currently 10% of Oxfam GB’s income) depends on the nature of the Brexit deal – eg whether the UK remains a member of the European Economic Area, and/or strikes a bilateral deal like Switzerland. That will take several years, but obviously includes a worst case scenario (Oxit? Sorry, couldn’t help myself…..), consisting of a double whammy in which DFID is butchered, at the same time as we lose access to at least a part of EU funds. There are lots of reasons to think that won’t happen, but these are sombre times.

There are wider considerations and big strategic choices to be made on how to respond. Here are a

couple that cropped up in a staff discussion this week.

Short term v long term: in the short term, there will be a spate of negotiations, new trade deals, Brexit talks with the EU etc, all of which could have profound impacts on development. There is a clear case for stepping up efforts to influence the UK Government in order to seize any opportunities and minimize damage.

On the other hand Brexit has revealed just how deep Britain’s divide is, a multifaceted inequality that has  generated not just income inequality but deep divisions over norms and identity. Would it be better to pull back from the day to day trench warfare of Whitehall and go long term, working with youth, investing more in development education, working on public attitudes to race and ‘Otherness’?

generated not just income inequality but deep divisions over norms and identity. Would it be better to pull back from the day to day trench warfare of Whitehall and go long term, working with youth, investing more in development education, working on public attitudes to race and ‘Otherness’?

More UK or Less? There is another option. If the decline in Britain’s influence is now terminal and accelerating, maybe UK NGOs should shift their emphasis to the countries that matter more, helping build citizenship and voice in the emerging powers, strengthening the pan-EU network on development?

OK, that’s about as much straw clutchism as I can muster. As ever, I welcome all comments and insights from the multiple conversations that must be going on right now

June 28, 2016

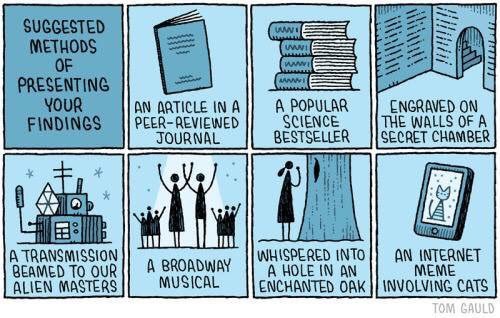

If you want to organize an event on How Change Happens this autumn, please let me know

My new book, How Change Happens, is published in October by OUP. I know, I know, there is no sight  so craven or humiliating as a writer desperate to promote their book. Any better ideas?

so craven or humiliating as a writer desperate to promote their book. Any better ideas?

The academic summer break is approaching fast, so as a first step, we’re inviting expressions of interest from universities, NGOs or anyone else in being part of the launch. The book is published on 27 October, but we’ll have copies from late September.

Here’s the deal:

What we provide: a walk through the issues in the book and a chance to challenge, engage, add your own perspectives etc; an author armed with powerpoint and pen (to sign books) and an unquenchable desire to shift product; books (paperbacks, a snip at £10 a pop)

What you provide: a few potential dates (some juggling likely to be required), a venue, cost of national transport and accommodation (if needed), a decent crowd (preferably at least 80 people), a named contact to receive books, sell them, then return dosh and unsold copies to Oxfam. Champagne optional. Rough dates:

Rough dates:

UK: mid Sept to 5 November, then January onwards

US and Canada: 7 November to 30 November

Australia and New Zealand: Late March/Early April 2017

The rest: let us know – we’ll improvise

If you’re interested, please get back to research@oxfam.org.uk, with ‘how change happens’ in the subject line, and we will start trying to sort out a schedule.

June 27, 2016

What does ‘How Change Happens’ thinking tell us about Brexit?

I was in Lisbon running a ‘How Change Happens’ summer school when the Brexit news came in, so I thought I’d apply an HCH analysis to a seismic event. I’m not an expert on UK politics, so this is bound to be pretty uninformed compared to the avalanche of post mortems in the press, but let’s see where it goes.

I was in Lisbon running a ‘How Change Happens’ summer school when the Brexit news came in, so I thought I’d apply an HCH analysis to a seismic event. I’m not an expert on UK politics, so this is bound to be pretty uninformed compared to the avalanche of post mortems in the press, but let’s see where it goes.

First up a disclaimer. As Timothy Garton Ash put it in a brilliant piece for the Guardian on Saturday ‘A

universal truth: nobody knows what is going to happen but everyone can explain it afterwards.’

I went back to the Context/Institutions/Agents/Events typology I used in From Poverty to Power. I’ll run through some of those, then reflect on what’s missing.

Context: Multiple long-term shifts influenced the result. Demographics: An ageing population combined with higher propensity to vote among older people who are much more  likely to be anti-EU (see table). Globalization and rising inequality prompted a deep sense of alienation and disconnect from the decisions of those in power. Syria and Europe’s half-hearted response both fueled a sense of an island under siege and further discredited the EU project.

likely to be anti-EU (see table). Globalization and rising inequality prompted a deep sense of alienation and disconnect from the decisions of those in power. Syria and Europe’s half-hearted response both fueled a sense of an island under siege and further discredited the EU project.

Institutions: A deep democratic deficit/hollowing out at all levels. The Eurozone meltdown tarnished the EU’s already damaged reputation. The 2008 financial crisis led to a general feeling of malaise and the MPs expenses scandal deepened scepticism about politicians and their arguments. No-one believes ‘we are all in this together’ any more. As John Cruddas argues, the Labour Party seems to have become the voice of the liberal metropolis, unable to respond to the sense of an Englishness under threat, as Tyler Cowen puts it.

Then there’s the institution of the referendum itself, which offers the public the chance to make a one-time statement on the state of the nation – a form of mass therapy in which it proved impossible to keep the focus on EU membership when people wanted to give the government a kicking on entirely separate issues, like ‘too many Muslims’.

Agents: Where to start? In terms of leadership, this useful piece identifies 12 key players and their  roles. You could count the press as either agents or institutions, but they were clearly stacked in favour of Brexit by those other influential agents, their owners. Leading players’ motives were in many cases petty and careerist/party positioning, compared to the profound consequences of the vote, and the aftermath is surely likely to ratchet up public disillusionment and anger, especially among Leave voters who saw promises being broken within days of the vote, and who may well end up suffering the most from the debacle of the next few years.

roles. You could count the press as either agents or institutions, but they were clearly stacked in favour of Brexit by those other influential agents, their owners. Leading players’ motives were in many cases petty and careerist/party positioning, compared to the profound consequences of the vote, and the aftermath is surely likely to ratchet up public disillusionment and anger, especially among Leave voters who saw promises being broken within days of the vote, and who may well end up suffering the most from the debacle of the next few years.

But the key agents are, I suppose, the voters themselves, 17 million of whom expressed their dissatisfaction with the status quo, their sense of a way of life under threat and poked a remote and arrogant political elite in the eye. It may have been a national outburst of nostalgia for a world seen through rose-tinted specs, or an excessive fear of the future and change, but it was obviously deeply felt by many, and too glibly dismissed by the establishment (remember Gordon Brown and Gillian Duffy?).

Events: While some relatively distant events such as the financial crisis, or the Syrian exodus, clearly influenced the poll, the only major event of the campaign was Jo Cox’s murder, which had much less impact than we anticipated (in the end, her constituency even voted Leave).

That provides a kind of X ray of the forces and actors involved, but misses some big pieces:

Powerful narrative, shame about the content

Narratives and Norms: The hollowing out of democratic debate has been accompanied by a transition to ‘post-truth politics’, in which experts and expertise of all kinds are dismissed and people are urged to vote on their feelings. At the same time, the level of alienation is such that many people seemed to think the referendum would have no impact on anything real, so voted Leave as a protest vote. One interesting post mortem goes even further:

Amongst people who have utterly given up on the future, political movements don’t need to promise any desirable and realistic change. If anything, they are more comforting and trustworthy if predicated on the notion that the future is beyond rescue, for that chimes more closely with people’s private experiences.

Having seen the initial meltdown after last Thursday, many Leavers are reportedly having second thoughts about this odd form of electoral nihilism – promptly christened ‘Regrexit’.

The referendum result was the strongest proof yet that in many circumstances, narrative trumps

Social Media word clouds show the different narratives at work

evidence. ‘Take back control’ and anxiety about immigration resonated more than any number of ‘IMF predicts Brexit would trigger recession’ type headlines. No-one believes it will affect them. It’s feelings not facts, people.

One dog that didn’t bark was that the vote was gender neutral. I would have expected a gender bias in favour of remain, especially given the male face and machismo of the Leave campaign – anyone seen a good gender analysis?

Coalitions: There weren’t two sides in this, there were dozens, forced by the referendum into uncomfortable cohabitation. As my friend Matthew Lockwood says ‘the Leave vote is actually made up of some distinct different constituencies: some hard core libertarians, some neo-liberals, some old fashioned Tory nationalists, then the populist working class left-behind group. Their agendas are actually incompatible and the wheels will come off, arguably already are.’ The same equally applies to the Remainers, who couldn’t even get Tory and Labour leaders (both supporters) on the same platform.

Dynamics: So put that all together and we have a perfect storm, a spectacular own goal prompted by demography, the big tides of post 2008 Europe, the hollowing out of British democracy, David Cameron’s preference for tactics over strategy, Labour’s leadership vacuum, and ‘events, dear boy’ as Harold MacMillan, another UK PM, apparently never said.

Attribution: This is really just a list of contributory factors, but how on earth could you even try to weight the importance of these different factors, given that they are apples and pears and all feed off each other? Over to the measurement gurus on that one.

Overall, this exercise and framework feels like a handy way of synthesizing multiple factors, rather than adding any particular explanatory power. Useful?

What have I missed? Over to you and do please suggest links to good analytical post mortems – this is going to be a case study for decades to come!

June 26, 2016

Links I Liked

Blimey, where to start? Think I’ll do an initial ‘how change happens’ post mortem piece on Brexit tomorrow, and just stick to the pre-poll run-up today, because the final days of the EU referendum

Blimey, where to start? Think I’ll do an initial ‘how change happens’ post mortem piece on Brexit tomorrow, and just stick to the pre-poll run-up today, because the final days of the EU referendum  campaign produced some fine humour – it already seems like a bygone age. Rhodri Marsden belatedly took a leaf out of the Leave campaign’s approach to factiness.

campaign produced some fine humour – it already seems like a bygone age. Rhodri Marsden belatedly took a leaf out of the Leave campaign’s approach to factiness.

And should his political fortunes prosper, let’s hope Boris Johnson’s grasp of government is better than his understanding of the purpose of capos (h/t Rob Manuel).

John Oliver did his bit for Remain, providing this potty-mouthed cover version of the European anthem, Ode to Joy. One of the cleaner lines ‘we would all be bat shit crazy if we vote for leaving it’. Ah.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HF-IlQ1bcQA

Back to the rest of the world.

Useful update on SDG process from Claire Melamed. Is it en route to implementation/traction or oblivion? (she says the former)

Britain’s Development Minister Justine Greening showed both timing and wit, with this ‘coming out’ tweet on the day of the big Pride parade.

Britain’s Development Minister Justine Greening showed both timing and wit, with this ‘coming out’ tweet on the day of the big Pride parade.

This may be tempting fate after recent events, but is the US election already over? The Trump campaign is in disarray, while Clinton steaming ahead.

I spent most of last week in Portugal, where I had to admire Ronaldo’s approach to intrusive microphones (if not his declining football talents or alarming suntan)

June 23, 2016

How can a top development thinktank improve its communications?

Well it feels like the world just ended, but thought I’d post this anyway. Life goes on and all that.

The title to this post was my exam question for a recent discussion with the comms team at ODI. My initial reaction was  ‘you’re top of the heap already, relax’, but then I got to thinking about a couple of areas where ODI, and most other development ‘knowledge brokers’ (or whatever they call themselves these days), can sharpen up.

‘you’re top of the heap already, relax’, but then I got to thinking about a couple of areas where ODI, and most other development ‘knowledge brokers’ (or whatever they call themselves these days), can sharpen up.

Where are the personalities?

The ODI is full of interesting, quirky, funny people, but you would never guess that from the website or the output. Why not? Apart from anything else, personality boosts traffic. Why not get ODI staff vlogging on their field visits, to give a sense of what they do and who they are? Why not let people sign up for notifications of blogs by named ODI staff, rather than the corporate beast? Where’s the cult of personality around the Director?

Can you help us read LESS?

Sure, ODI churns out vast amounts of research, and wants us to read it, but one of the main kinds of feedback I get on this blog is ‘thanks for reviewing XX, because you saved me loads of time reading it’. I really like the ODI’s quarterly ‘resilience scan’ for the same reason (wish they would do one on Doing Development Differently). It is also really good at infographics, videos, blogging its papers etc. Most people in the aid and development business (and everywhere else) suffer from information overload, so people and institutions that can summarize, signpost and shortcut are worth their weight in gold (and printer ink). Book reviews, ‘listicles’ – ’10 things you need to know about the latest development fuzzword’, ‘bluffer’s guide to social enterprise, payment by results, resilience for dummies etc’. Or why not pick up the World Bank’s David Evans’ trick of summarizing all the papers at a given conference, with links (I think 150 papers is probably his record so far)?

Sure, ODI churns out vast amounts of research, and wants us to read it, but one of the main kinds of feedback I get on this blog is ‘thanks for reviewing XX, because you saved me loads of time reading it’. I really like the ODI’s quarterly ‘resilience scan’ for the same reason (wish they would do one on Doing Development Differently). It is also really good at infographics, videos, blogging its papers etc. Most people in the aid and development business (and everywhere else) suffer from information overload, so people and institutions that can summarize, signpost and shortcut are worth their weight in gold (and printer ink). Book reviews, ‘listicles’ – ’10 things you need to know about the latest development fuzzword’, ‘bluffer’s guide to social enterprise, payment by results, resilience for dummies etc’. Or why not pick up the World Bank’s David Evans’ trick of summarizing all the papers at a given conference, with links (I think 150 papers is probably his record so far)?

Interactivity

You go to ODI to receive wisdom. That doesn’t encourage much interaction – very few comments on most blogs, no polls, few debates on genuine dilemmas. That also has a dampening effect on potential engagement by the public.

Snakeoil v Scattergun

It’s interesting to compare ODI with its main competitor in the aid/development sector – the Center for Global Development. CGD has arguably got a much sharper approach to marketing – it takes time to develop a new idea, invests in finding a good name for it (‘Cash on Delivery’, ‘Commitment to Development Index’), puts together teams to work on it, and then remorselessly bangs home the need for the product (whatever the problem, CoD seems to be part of the solution). ODI is much more ‘let a hundred flowers bloom’ and then different sectors can pick the flowers they like. Personally, I prefer the ODI model – more diverse, more compatible with messy, complex systems, but you do dilute the brand, sacrificing profile and possibly impact.

That was my initial tirade. The reactions from the ODI comms gurus were interesting. They were

For some reason they don’t always say ‘whoopee’

worried that warts and all ‘vlogs from the field’ might dilute the aura of authority and expertise they work hard to build. I disagree – as long as you clearly demarcate ‘work in progress’ from final product, the fact that researchers do actually get out of London and talk to poor people can only enhance their credibility.

Their other response was more tricky. Some researchers are natural communicators, but others are, how can we put it, happier with their spreadsheets. How to drag them blinking into the light? My advice would be don’t even try – bitter experience has shown me you can’t force introverted researchers into becoming bloggers, at least not good ones. Better to spot the researchers who like communicating and support them.

The support can be direct (eg if they don’t like writing accessibly, get them to vlog, or interview them, write it up and get them to approve the text). Be ready to mentor them as they start trying stuff out. Lots of upfront training may be counterproductive – it just turns something easy like making a video on your phone, into a big chore.

But support can also be indirect, through improved feedback loops. Why not circulate a list of staff’s media hits every month (traditional and social media)? Or get audiences to feed back on panellists and presentations, then tell everyone in ODI the results? That could shift institutional incentives towards comms a bit.

But support can also be indirect, through improved feedback loops. Why not circulate a list of staff’s media hits every month (traditional and social media)? Or get audiences to feed back on panellists and presentations, then tell everyone in ODI the results? That could shift institutional incentives towards comms a bit.

And the one massive thing I completely forgot to mention, so will do so now – MOOCs. ODI is totally suited to run Massive Open Online Courses that fill the gap between social media and reading inaccessible research. What’s holding them back?

Any other suggestions for ODI?

And here’s a vlog summary recorded early in the morning in Lisbon. For some reason I’m talking very fast despite geese honking and a mild hangover- not a good look, I think we can agree.

June 22, 2016

Will Bill Gates’ chickens end African poverty?

Joseph Hanlon and Teresa Smart are unimpressed by a new initiative, but

Joseph Hanlon and Teresa Smart are unimpressed by a new initiative, but  disappointingly avoid all the potential excruciating puns

disappointingly avoid all the potential excruciating puns

Bill Gates announced on 7 June that he is giving 100,000 chickens to the poor because chickens are “easy to take care of” and a woman with just five hens in Africa can make $1000 per year. For Mozambique where we work, this is remarkable – fewer than 2% of Mozambican farmers make $1000/year. What a wonderful idea. Why did no one think of this before?

Actually, they did. For a decade, Mozambique has had its district development loan fund, known locally at the “7 million” because the initial fund was Meticais 7 million per district. Most farm families have chickens running around, and one of the most common requests for loans from the fund is from people who agree with Gates that chickens are “easy” and they want to expand to commercial production. Nearly all fail, and cannot repay their initial loan. Perhaps the problem is not the initial five hens.

Ed Wethli, an old friend who worked with chickens in Mozambique, says Gates is half right. “Village  chickens are the true ‘free-range’ chickens in that they wander around wherever they like with no boundaries, often roosting in trees at night. They find most of their own feed, are good at hatching and mothering young chicks and they have the ability to survive under harsh conditions.” They are an important part of local life, and are a valuable food source as well as being used as gifts and for ceremonies. And a few are sold to neighbours.

chickens are the true ‘free-range’ chickens in that they wander around wherever they like with no boundaries, often roosting in trees at night. They find most of their own feed, are good at hatching and mothering young chicks and they have the ability to survive under harsh conditions.” They are an important part of local life, and are a valuable food source as well as being used as gifts and for ceremonies. And a few are sold to neighbours.

The problem is scaling up to commercial production, with larger flocks that no longer live in trees but require coops, feed, and treatments to prevent parasites and Newcastle disease. And they require markets. Small chicken growers in Mozambique usually fail because they cannot produce at a cost below those of the larger growers. In even remote local markets, frozen chickens produced in Mozambique or imported from Brazil and South Africa are cheaper than local live chickens. Local chickens taste better,  but they are a luxury product. And margins are tight – to make a profit a farmer must be able to grow and sell the chicken in five weeks; if it takes just one extra week, then all the profit is lost to extra feed costs. With veterinary and other technical support, village chicken production can be made profitable, although more at the level of $100 per year rather than $1000. But in Mozambique, that kind of support is rarely available.

but they are a luxury product. And margins are tight – to make a profit a farmer must be able to grow and sell the chicken in five weeks; if it takes just one extra week, then all the profit is lost to extra feed costs. With veterinary and other technical support, village chicken production can be made profitable, although more at the level of $100 per year rather than $1000. But in Mozambique, that kind of support is rarely available.

Over three decades, Brazil developed an entirely different model. With intensive support by the Brazilian development bank BNDES and tight regulation by the government, Brazil has become the second largest chicken producer in the world and the largest exporter. The chickens are raised by tens of thousands of family farmers, but on a contract basis to large companies which provide day-old-chicks, feed, medication, technical assistance and, most importantly, a guaranteed market.

There are two lessons here. First, this industry was not created by the private sector, but by long term intensive investment by the government – it is the state the builds capitalism. Second, small family farmers can be more effective than large producers, if they are integrated in a value chain.

Fifteen years ago most chickens on the market in Mozambique were imported, mainly from Brazil.

Nigerian chicken farm

Neoliberalism was still in force and donors and lenders would not let the government intervene in agriculture. But two US NGOs, TechnoServe and Clusa (Cooperative League of the USA – many people do not realise that in the capitalist US, a majority of farmers are members of cooperatives), began work to build local chicken production and local soya growing to feed the chickens cheaply. By 2008 local chicken production exceeded imports. It took another four years of intensive, on the ground, work – cutting costs and losses and introducing more productive chicken breeds – to build the industry up to the point that the private sector was interested. Now the most effective producers follow the Brazilian out-grower model, with families rearing the chickens and a central company providing day-old-chicks, feed, medication and markets. Indeed, it was so successful that we called our most recent book Chickens and beer: A recipe for agricultural growth in Mozambique.

The best family farmers are now earning $750 per year, which in Mozambique is a lot of money. Unlike Bill Gates’ five hens or the families who try to expand with loans, these farmers receive hundreds of day-old-chicks, an effective support package, and are sure of being able to sell what they produce. And those chickens on the market are less costly than Brazilian imports, providing an inexpensive source of protein to local people.

Chicken distribution in Burkina Faso

But knowing what works is not useful, if it is “wrong” – in this case because it was neither charity (giving away hens) nor the private sector, but an intensive development effort by what might be called “the international public sector”. However, the international financial institutions are now stepping in to correct the situation. Odebrecht, the giant Brazilian construction company (whose boss was jailed for 19 years in March for corruption) has already received $550,000 from the Agriculture Fast Track Fund (set up by the US, Sweden and Denmark) and the Africa Development Bank to plan an $82 million installation to go from field to fork, producing maize and soy for feed; having a hatchery, slaughterhouse and processing plant; and marketing. It hopes to raise money from the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation and produce a quarter of Mozambique’s chickens. If successful, the project will put out of business thousands of Mozambican small commercial chicken producers, who could not compete. Is this really the best way for the World Bank and African Development Bank to promote development?

As usual, the aid industry can only see the two extremes and ideas that come from outside – Bill Gates’ five hens or Odebrecht’s millions of chickens. The successes in the middle, and the successes developed locally, are ignored. In Mozambique thousands of Mozambican farmers are already raising their income by producing good value chickens – but that does not grab headlines. So let us hand out hens instead.

Joseph Hanlon is visiting senior fellow at the London School of Economics and visiting senior research fellow at the Open University.

Teresa Smart is a senior research associate at the Institute of Education, University College London.

P.S. The Bolivian government was also underwhelmed by the chicken offer.

June 21, 2016

Jo Cox would have been 42 today. Here’s what she was like to work with.

Today would have been Jo Cox’s 42nd birthday. Celebratory events are being held around the world

Jo as head of advocacy at Oxfam House. Photo: Kate Raworth

with the hashtag #MoreinCommon, taken from her maiden speech in Parliament: ‘W e are far more united and have far more in common with each other than things that divide us’. My ex-boss Phil Bloomer, who worked with Jo for many years at Oxfam, gave this lovely tribute to an event in Oxford at the weekend.

Jo would have been so pleased to see so many people here today from the many causes she fought for: dear Oxfam colleagues, sisters and brothers in the Labour Party and trade unions, feminists, and the good folk of Oxford.

Jo was one of the most kind, caring, and committed people I have had the privilege to know.

She could also make herself a right royal pain in the back-side if she profoundly disagreed with you: a lesson many political leaders learnt too late, and to their cost.

I first met Jo when she was fresh out of university, when she worked for Glenys Kinnok MEP (at the time, known colloquially as the MEP for South Wales and Soweto because of her domestic and international work). Jo would engage me in conversation as I waited for Glenys – often about the appalling nature of my clashing ties, but always about issues such as the current detention condition of Aung San Suu Kyi in Burma, or the changes happening so rapidly in South Africa. Jo could chat to anyone – even me.

Because Jo loved People: she was cheeky, with a dry, sardonic humour, often aimed at herself. Jo could happily spend hours playing with refugee children in a camp, or engaging rather la-di-da intelligentsia in an international think tank. It’s also why Jo, with Brendan, spent their summer holidays working with war orphans in Sarajevo.

But wherever Jo was, she was always herself. Authentic. I never saw her put on airs and graces, nor speak down to anyone.

Jo was Fearless. Or at least could make herself appear to be when it mattered. In the early 2000s, Jo was in her late 20s, and looked about 17. She had a very broad Yorkshire accent (much broader than mine, mind), yet was unanimously appointed to the Head of Oxfam’s Brussels office, due to the power of her intellect, persuasion, and passion.

This meant regular meetings with the EU Trade Commissioner, Peter Mandelson, and his coterie of powerful advisers. Peter Mandelson, as many of you will know, is a man of sophisticated and urbane manner, who quickly had to adjust his perception and approach to the meeting when feisty Jo, brimming with expert trade facts (many of them provided by people I can see amongst us tonight), gave him a  master class in European Trade Policy, and how it must change to benefit the poor of the world.

master class in European Trade Policy, and how it must change to benefit the poor of the world.

We laughed together for hours afterwards as we recollected the change in their expressions through the meeting, from warm but patronising condescension, to terror.

Jo could do this because Jo loved Justice. She felt it in her guts. Jo was moved almost too much by the suffering she worked alongside in Darfur, Sudan. Jo devoted years of her life to the plight of refugees.

But Jo also knew how to pressure repressive governments that force people to flee their homes. She organised a visit of eight global women leaders to Darfur: led by Mary Robinson, with African economists and parliamentarians. Jo then organised their tour of the world’s capitals to put maximum international pressure on the regime in Khartoum from Washington DC, London, Paris, Brussels, and Berlin.

And finally, Jo loved Love. Jo knew in her bones its transformatory power. Perhaps because she came from a loving family, and a close working class community in Leeds.

Jo loved her kids with the same furious passion – dashing home from Parliament to tuck them into bed at

The day before she died, Jo, Brendan and their kids joined the Remain flotilla ahead of tomorrow’s referendum

night, before dashing back for another late night vote.

And Jo’s politics were inspired by love: when she made her maiden speech that “while we celebrate our diversity, we are far more united, and have far more in common with each other than things that divide us” she spoke to that love.

Jo’s politics embodied the great words of Martin Luther King, also a victim of political murder: “Power without love is reckless and abusive, and love without power is sentimental and anaemic. Power at its best, is love implementing the demands of justice, and justice at its best is power correcting everything that stands against love.” That was how Jo conducted herself as a leader at Oxfam, and as an MP in our democracy.

In this dark hour we live through, Mary Robinson wrote to us from Ireland today and said “A light can shine through when it has the integrity of everything Jo lived for.”

Let’s all make sure that happens.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers